Abstract

Synthesis of multiple extracellular lipases in Candida rugosa has been demonstrated. However, it is difficult to characterize the expression spectrum of lip genes, since the sequences of the lip multigene family are very closely related. A competitive reverse transcription-PCR assay was developed to quantify the expression of lip genes. In agreement with the protein profile, the abundance of lip mRNAs was found to be (in decreasing order) lip1, lip3, lip2, lip5, and lip4. To analyze the effects of different culture conditions, the transcript concentrations for these mRNA species were normalized relative to the values for gpd, encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. In relative terms, lip1 and lip3 were highly and constitutively expressed (about 105 molecules per μg of total RNA) whereas the other inducible lip genes, especially lip4, showed significant changes in mRNA expression under different culture conditions. These results indicate that differential transcriptional control of lip genes results in multiple forms of lipase proteins.

Lipases (EC 3.1.1.3) from the nonsporogenic yeast Candida rugosa (formerly C. cylindracea) are very important industrial enzymes which have been widely used in biotechnological applications such as the production of fatty acid, synthesis of various esters, and kinetic resolution of racemic mixtures (10, 14, 22, 29, 40, 43, 44). Crude enzyme preparations are used in most applications, and enzymes from various suppliers have been reported to show variations in their catalytic efficiency and stereospecificity in various applications such as resolution of racemic 2-(4-hydroxyphenoxy) propionic acid (2). After our discovery of multiple enzyme forms with different substrate specificities and thermostabilities in a commercial C. rugosa lipase preparation (39), two to six enzyme forms were detected in subsequent studies (4, 9, 36, 37). More recently, we discovered that three commercial C. rugosa lipase preparations differed in protein composition, which accounted for the difference in their catalytic efficiency and specificity (5). This was related to the different culture conditions used. It was supported by the observation that different inducers in the culture media of C. rugosa changed the multiple form patterns and therefore the specificity and thermostability of crude lipase preparations (5).

The multiplicity of extracellular lipases in fungi (3a, 17–19, 32) has been attributed to a change in gene expression, variable glycosylation, partial proteolysis, or other posttranslational modification. After the cloning of five lipase genes (lip1 to lip5) from the C. rugosa genome (24, 26), a change in gene expression has been suggested to be the most probable mechanism for the enzyme multiplicity. However, the high similarity of same-sized deduced amino acid sequences in these mature proteins (66% identity and 84% similarity) makes it difficult to purify and identify the lipase gene products (27).

For highly related genes, the conventional methods in mRNA analysis are not specific and sensitive enough to distinguish and quantitate individual mRNAs. It is difficult to distinguish the transcription pattern of genes with a high degree of identity by Northern blot analysis. Although the nuclease protection assay has the ability to discriminate among closely related genes, this method, like Northern blotting, is not sensitive enough to detect small amounts of mRNA and permits only crude quantitation. The competitive reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) technique (3, 12) may be a feasible alternative to obtain quantitative information on the highly related lip genes at the transcriptional level owing to its high sensitivity and specificity (35, 41).

Although the lip1 cDNA has been isolated from C. rugosa (21), there is no evidence that the other four genomic lipase-encoding sequences isolated are functional. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms of the individual lip gene regulation remain unclear. In this report, we describe a modification of the competitive RT-PCR method to detect and quantitate the five lip mRNA transcripts and thus confirm the functional expression of the five lip genes. By using this technique, it is possible to demonstrate the differential expression of the five lip genes in the presence of different inducers that are known to be able to increase C. rugosa lipase production (5, 13, 42).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganism and medium.

C. rugosa ATCC 14830 was cultured in YM growth medium (0.3% yeast extract, 0.3% malt extract, 0.5% peptone, 1% dextrose) at 30°C for 24 h. The concentrations of additives are specified for the different experiments.

Bacterial transformation.

Plasmid DNA was transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen) by the CaCl2 method and extracted from ampicillin-resistant colonies by the alkali lysis method (38).

RNA preparation.

Total RNA from C. rugosa was isolated by a modification of the method of Köhrer and Domdey (23). Cultured cells (5 ml) were collected by centrifugation (3,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min), resuspended in 300 μl of sodium acetate buffer (50 mM sodium acetate, 10 mM EDTA [pH 5.0]), and then transferred to a 1.5-ml microtube containing 0.3 g of glass beads (pretreated with 1 M HCl and autoclaved). After two cycles of hot-phenol extraction, total RNA was collected by ethanol precipitation.

To eliminate contaminating genomic DNAs, two purification methods were used. (i) RNase-free DNase I (20 U; Promega) was mixed with 50 μg of the total RNA in RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol [pH 8.3]) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in a total volume of 50 μl. The RNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. (ii) The RNA pellets obtained from the hot-phenol extraction were dissolved in 500 μl of prechilled denaturing solution (4 M guanidine thiocyanate, 42 mM sodium citrate, 0.83% N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), and 50 μl of 2 M sodium acetate (pH 4.0) was then added to provide acidity. After 500 μl of a mixed organic solvent (phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, 25:24:1) was added, the mixture was vigorously vortexed for 1 min and chilled on ice for 3 min. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g and 4°C for 15 min, the aqueous phase was transferred to a new microtube and RNA was precipitated twice with an equal volume of isopropanol at −20°C for 30 min.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA in a 20-μl reaction mixture by using oligo(dT) primers, deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates, and SuperScript II enzyme as specified by the manufacturer (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). To increase the efficiency of PCR initiation, RNase H (2 U; Life Technologies) was added and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 min. PCR amplification was performed in a 25-μl reaction volume containing 0.5 μl of RT reaction solution, each deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate at 100 μM, 5 pmol each of 5′ and 3′ primer, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 0.01% (wt/vol) gelatin, and 0.25 U of DynaZyme (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland). The reagents for RT and PCR were always prepared as a single reaction mixture and then divided among different tubes. PCR was carried out in an Omnigene thermal cycler (Hybaid, Teddington, United Kingdom) on the following cycle program: one cycle of 94°C for 3 min and 72°C for 1 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s; and a final 10-min extension step at 72°C.

Cloning of template DNAs.

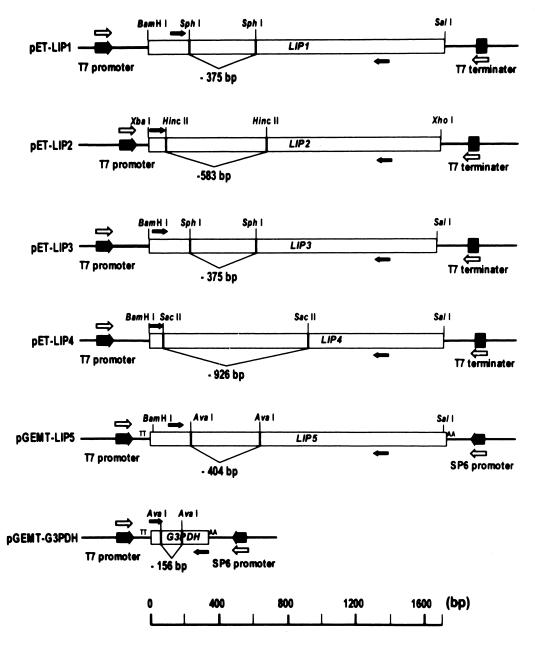

The full-length lipase-encoding cDNA fragments were obtained by RT-PCR with specific primers based on the published sequences (24, 26). The PCR products with created flanking restriction sites were digested with restriction enzymes and ligated into pET-23a (Novagen) or pGEMT vector (Promega). A schematic presentation of the plasmids is given in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Plasmids for deletion-containing competitive templates and relative positions of PCR primers. Open arrows indicate primers for the generation of competitor DNAs. Solid arrows indicate those for competitive PCR. The scale shows the nucleotide size of the DNA fragment.

To obtain the C. rugosa gpd gene, consensus sequences were determined by aligning multiple related DNA sequences from a database. The partial C. rugosa gpd DNA fragment was obtained by RT-PCR with degenerative primers designed from the consensus sequences indicated in Table 1. This DNA fragment was then cloned into the pGEMT vector (Promega), and its sequence (327 bp) was determined on both strands.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for competitive RT-PCR

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′→3′)a | Size (bp) of PCR productb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Target | Competitor | ||

| LIP1sp-5′ | CGGCTCGCTCGATGGCCAGAAGTTCACG (180–207) | 1,188 | 813 |

| LIP2sp-5′ | GAAGCTCTGTTTGCTTGCTCTTGGTGCTG (3–31) | 1,365 | 782 |

| LIP3sp-5′ | TCCTGCTCATTGCCTCGGTGGCTGCC (20–45) | 1,348 | 973 |

| LIP4sp-5′ | TACTCTCGCTCATTGTCTCGGTGGCCGCG (17–45) | 1,351 | 425 |

| LIP5sp-5′ | TCCGCTTCAAGGACCCTGTGCCGTACCG (152–179) | 1,216 | 812 |

| LIP-3′ | CCCAGAAGCTGCTTCAGGAGGAACGAGTAC (1338–1367) | ||

| GPD-5′ | GGTGCBGCYAAGSSYGTCGGYAAGG (1–25) | 327 | 171 |

| GPD-3′ | GTARCCSYAYTCGTTRTCGTACC (305–327) | ||

Each specific 5′ primer has a 3′-end nucleotide unique to a lip sequence. The nucleotide numbers corresponding to the coding sequences of the lip genes are shown in parentheses. The portion of LIP-3′ primer corresponding to lip2 is from bp 1335 to 1364. The symbols in the degenerate GPD primers are as follows: B for C, G or T; Y for C or T; S for C or G; and R for A or G. The GPD-5′ and GPD-3′ primers were used to clone the partial sequence of the gpd gene.

The PCR products were generated by using the respective 5′ primers and the consensus 3′ primer (LIP-3′).

Competitive RT-PCR.

Competitive RT-PCR was conducted as previously described for RT-PCR, except that known concentrations of competitor DNA, an exogenous template as an internal PCR standard, were spiked into a series of PCR tubes containing constant amounts of cDNA generated from total RNA. The competitor DNA has the same primer recognition sites as the target and thus competes with the target for the same primers during the amplification. It is important to select the appropriate lip competitor DNAs and the specific primer sets used for competitive RT-PCR, since one primer set must amplify only one lipase gene among the highly related gene family. Competitor DNA vectors (Fig. 1) were constructed by restriction digestion within each lipase-encoding region followed by self-ligation; therefore, after competitive PCR, the products of target and competitor DNA could be distinguished by their size. The competitor DNAs were obtained by PCR with primer pairs present in the vectors. To remove PCR template and primers, the competitor DNA fragment was eluted after agarose electrophoresis. The specific primer set, as shown in Table 1, had a unique and specific 5′ primer and a common 3′ primer for each lipase gene. These primer sets were tested for specificity and efficiency by PCR (data not shown).

Determination of the quantity of the competitor DNA used to assess the amount of target cDNA is important for precise quantitation by competitive RT-PCR. An accurate quantity of the competitor DNA was determined by capillary gel electrophoresis (CGE). All CGE analyses were conducted on the P/ACE system 5510 (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, Calif.). Separations were carried out in the reversed mode (anode at detector side) with the Beckman eCAP dsDNA 20,000 kit. UV on-line detection was set at 254 nm with a running temperature of 20°C. Samples were injected for 10 s by pressure, and separation was performed at 9.0 kV for 25 min in a 47-cm capillary tube. Data was collected and analyzed automatically using Gold Software, Version 8.1 (Beckman). The peak of the competitor DNA was identified by the retention time. The concentration of the competitor DNA was determined from the calibration curve derived from the simultaneous injection of a molecular weight standard. The precise amount of the competitor DNA was calculated by integrating the area of its peak on a CGE chromatogram. The same quantity of competitor DNA was rechecked by electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining.

Detection and quantification of competitive PCR products.

Each PCR mixture (10 μl) was immediately loaded onto 1% agarose gels in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA). Electrophoresis was then performed at 100 V and room temperature for 60 min. After migration, the gels were stained with a fluorescent double-stranded DNA-specific stain (SYBR Green I; Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) for 20 min and then directly scanned and visualized with the STORM system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.). The SYBR Green I-bound DNA bands in the gel were excited at 497 nm and emitted at 520 nm.

The chemifluorescence data were obtained by computer-based video image analysis (ImageQuaNT software; Molecular Dynamics). The fluorescence intensities were proportional to the amount of DNA in the samples. To correct for differences in molecular weight and to enable direct comparison of the corrected intensities of the competitor bands with the target bands, the fluorescence intensity of the competitor band was multiplied by a factor of target size (bp)/competitor size (bp). In the determination of the competition equivalence point (EP), the log10 of the intensity ratio of competitor to target was plotted as a function of the log10 of the initial amount of competitor (33). By linear regression analysis, the fluorescence intensity of the competitor band should be equal to that of the target band at the EP, and their ratio should be equal to 1. Interpolation on the plot for a y axis value of 0 (log10 1 = 0) gives the copy number of target present in the test sample.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence of C. rugosa gpd has been submitted to the GenBank database under accession number AF025307.

RESULTS

Validation of competitive PCR analysis.

To ensure a successful analysis of gene expression within the highly conserved lip gene family, the quality of the RNA, the design of competitor DNAs and specific primer set, the choice of control gene, the quantitation of competitor DNAs, and the evaluation of competitive PCR results were considered.

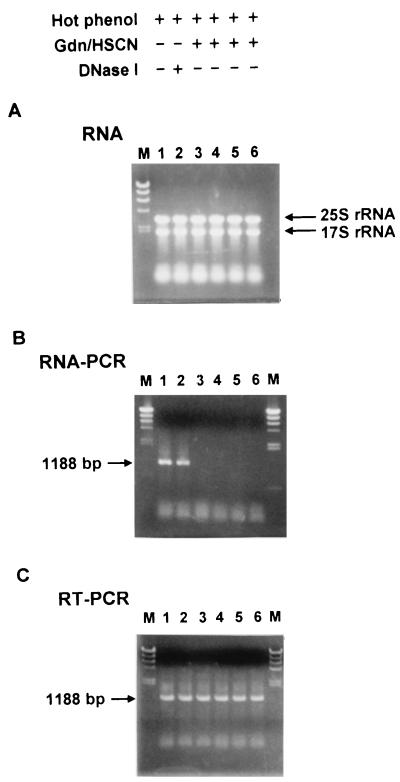

Because all the five cloned C. rugosa lip sequences are intronless genes (24, 26) frequently discovered in yeast-like fungi (15), any genomic DNA contamination during the RNA preparation will lead to false-positive and ambiguous results in RT-PCR. Therefore, an accurate quantitation with the competitive RT-PCR substantially relies on the quality of the RNA preparation. The RNA was purified by a hot-phenol extraction method as well as the additional procedures, including treatment with either DNase I or guanidine thiocyanate (Gdn/HSCN) and N-lauroylsarcosine (6, 8) in RNA preparation prior to RT. RNA samples prepared under various culture conditions by different procedures were demonstrated to have good integrity (Fig. 2A); however, no genomic DNA contamination was observed only in the RNA samples isolated by the Gdn/HSCN procedure with RNA-PCR (Fig. 2B). Consequently, the lipase gene could be PCR amplified only from the first-strand cDNA generated from the RNA isolated by the Gdn/HSCN procedure, instead of the genomic DNA, as shown in lane 3 to 6 of Fig. 2C. In conclusion, we have established an improved protocol for isolating high-quality RNA, free of contaminating DNA from fungi, which can be readily used in competitive RT-PCR to detect mRNA expression.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of RNA integrity, genomic DNA contamination, and lip gene expression by RT-PCR. C. rugosa was cultured in YM alone (lanes 1 to 3) or containing 1% olive oil (lane 4), 1% oleic acid (lane 5), or 1% Tween 20 (lane 6). RNA was isolated or treated by different methods as indicated. (A) RNA samples (5 μg per lane) were electrophoresed on a 1% native agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Arrows indicate the positions of the 25S and 17S rRNA bands. (B) Genomic DNA contamination was detected by RNA-PCR with prepared RNA as the template and the lipase-specific primers (LIP1sp-5′ and LIP-3′ in Table 1). The position of lip1 is indicated by the arrow. (C) Gene expression of lip1 was analyzed by RT-PCR with cDNA generated from related RNA as the template. M, λ/HindIII DNA size markers.

The choice of the copy number range of competitor DNA is critical for quantitative sensitivity. The appropriate range for the competitor DNA added to the PCR mixture was inferred from a comparison between a broad range of fivefold serial dilutions (4 to 0.00128 amol) and a narrow range of twofold serial dilutions (0.8 to 0.025 amol) (Fig. 3A). The results showed that a fine-tuned narrow range of competitor DNA would be coamplified with the target cDNA and that the patterns of PCR products (the ratios of target to competitor) would properly measure the quantity of lip transcripts.

FIG. 3.

Validation of competitive PCR analysis. (A) Titer determination of lip1 competitor with a constant amount of cDNA generated from RNA isolated from YM-cultured C. rugosa. Fivefold (lanes 1 to 6) (4 to 0.00128 amol) and twofold (lanes 7 to 12) (0.8 to 0.025 amol) serial dilutions of lip1 competitor were coamplified with a constant amount of cDNA. After 40 cycles of amplification, the products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The positions of the 1,188-bp lip1 target (T) and 813-bp competitor (C) PCR products are indicated. Lane M contains a HindIII digest of λ DNA as a size marker. (B) Analysis of relative changes in lip1 target levels by competitive PCR. cDNA samples generated from 125 and 62.5 ng of total RNA were amplified in the presence of twofold dilutions of lip1 competitor (the same as in panel A). A total of 40 cycles of PCR and electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel were performed. The gels were stained with SYBR Green I. The DNA products visualized by chemifluorescence were scanned and quantitatively analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The open and solid circles denote data derived from 62.5 and 125 ng of RNA, respectively.

We reconfirmed the sensitivity of the competitive PCR method by determining the effect of the increasing amount of cDNA. cDNA samples generated from 125 and 62.5 ng of total RNA were coamplified with twofold serial dilutions of the lip1 competitor. The copy numbers of lip1 transcript were calculated by determining the competition equivalence points in linear regression plots as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 3B). The correlation coefficients (r2) of the lines determined by least-square regression analysis were very close to 1. From mathematical considerations of competitive PCR (34), the slopes of the lines, ranging from 0.9 to 1.0, suggested that the amplification efficiencies of the target and the competitor were similar in the same reaction tube. The copy numbers of lip1 cDNA determined from the 125- and 62.5-ng RNA plots (Fig. 3B) were 2.60 ± 0.02 × 104 and 1.42 ± 0.01 × 104 molecules, respectively, giving a 1.83-fold difference (very close to the predicted value of 2.0-fold). In consequence, competitive PCR can be used to accurately analyze the lip gene expression in a quantitative manner.

Differential expression of C. rugosa lip genes under different culture conditions.

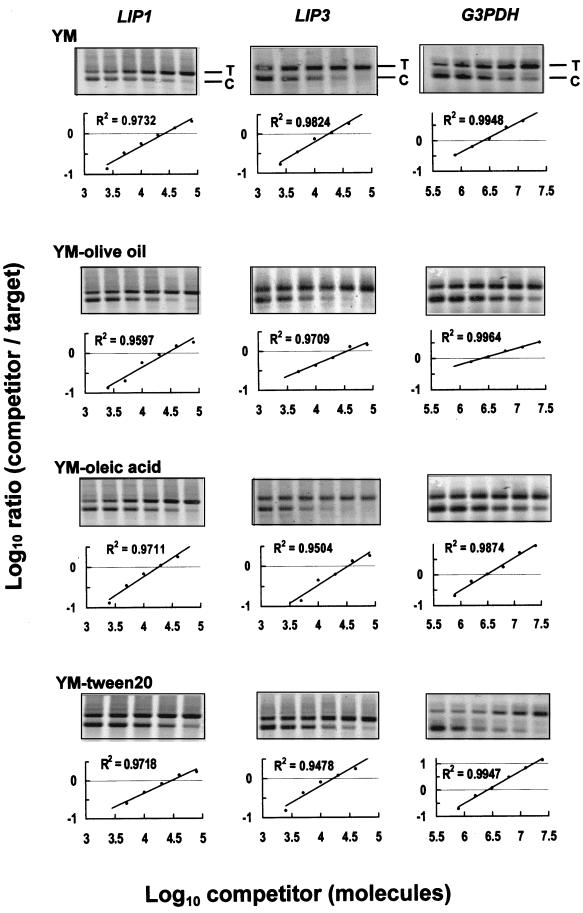

The expression of the different lip genes in various culture conditions was examined by competitive RT-PCR with specific primers and running for 40 PCR cycles. As shown in Fig. 4, abundant amounts of lip1, lip3, and gpd transcripts were observed. The copy numbers of lip1, lip3, and gpd transcripts were calculated by determining the competition EPs in regression plots (Fig. 4 and Table 2). Correlation coefficients (r2 values) and slopes of the regression lines were within the confidence limits. gpd, a housekeeping gene, was used as an experimental control because it was highly expressed (approximately 100-fold higher than lip1) and its expression pattern was seldom affected by various treatments (giving a mean of 2.12 × 107 ± 0.19 × 107 molecules per μg of total RNA). Experimental errors in the sample preparation or assay condition can be ruled out by normalizing the measured copy number of each lip transcript to that of the gpd transcript.

FIG. 4.

Quantitation of lip1, lip3, and gpd mRNAs by competitive RT-PCR. Twofold serial dilutions of the competitors (lanes 1 to 6) (0.8 to 0.025 amol for lip1 and lip3; 250 to 7.8 amol for gpd) were added to PCR mixtures containing a constant amount of cDNA generated from RNA isolated from C. rugosa cultured in YM, YM containing 1% olive oil, YM containing 1% oleic acid, or YM containing 1% Tween 20. The gpd gene was used as an endogenous standard for calibration among different culture conditions. After 40 cycles of amplification, the products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel stained with SYBR Green I. The gels were then scanned and quantitatively analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Quantitative plots are shown (insets). The positions of the corresponding target (T) and competitor (C) PCR products are indicated.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of specific mRNA expression under various culture conditions by competitive RT-PCR

| Target mRNA | Culture conditions | Slope (r2)a | EP (no. of copies per μg of total RNA)b | No. of copies per gpd mRNAc | Fold inductiond | Amt relative to lip1e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lip1 | YM | 0.98 (0.97) | (2.08 ± 0.02) × 105 | 1.05 × 10−2 | 1 | 1 |

| YM-olive oil | 0.81 (0.96) | (2.19 ± 0.13) × 105 | 1.12 × 10−2 | 1.07 | 1 | |

| YM-oleic acid | 0.92 (0.97) | (1.46 ± 0.06) × 105 | 0.60 × 10−2 | 0.56 | 1 | |

| YM-Tween 20 | 0.88 (0.97) | (2.38 ± 0.09) × 105 | 1.13 × 10−2 | 1.08 | 1 | |

| lip2 | YM | (1.04 ± 0.09) × 103 | 0.52 × 10−4 | 1 | 0.005 | |

| YM-olive oil | (2.80 ± 0.29) × 103 | 1.43 × 10−4 | 2.69 | 0.013 | ||

| YM-oleic acid | (1.29 ± 0.12) × 103 | 0.53 × 10−4 | 1.24 | 0.009 | ||

| YM-Tween 20 | (1.22 ± 0.03) × 103 | 0.58 × 10−4 | 1.17 | 0.005 | ||

| lip3 | YM | 0.85 (0.98) | (1.42 ± 0.03) × 105 | 0.72 × 10−2 | 1 | 0.68 |

| YM-olive oil | 1.01 (0.97) | (2.90 ± 0.15) × 105 | 1.48 × 10−2 | 2.07 | 1.32 | |

| YM-oleic acid | 0.90 (0.95) | (2.68 ± 0.15) × 105 | 1.10 × 10−2 | 1.53 | 1.83 | |

| YM-Tween 20 | 0.85 (0.95) | (1.33 ± 0.02) × 105 | 0.63 × 10−2 | 0.88 | 0.56 | |

| lip4 | YM | (2.45 ± 0.16) × 102 | 0.12 × 10−4 | 1 | 0.001 | |

| YM-olive oil | (5.22 ± 0.42) × 102 | 0.27 × 10−4 | 2.13 | 0.002 | ||

| YM-oleic acid | (9.92 ± 0.32) × 102 | 0.41 × 10−4 | 4.05 | 0.007 | ||

| YM-Tween 20 | (1.93 ± 0.08) × 103 | 0.92 × 10−4 | 7.89 | 0.008 | ||

| lip5 | YM | (7.70 ± 0.40) × 102 | 0.39 × 10−4 | 1 | 0.004 | |

| YM-olive oil | (1.60 ± 0.08) × 103 | 0.82 × 10−4 | 2.09 | 0.007 | ||

| YM-oleic acid | (1.55 ± 0.11) × 103 | 0.64 × 10−4 | 2.03 | 0.011 | ||

| YM-Tween 20 | (1.49 ± 0.18) × 103 | 0.71 × 10−4 | 1.95 | 0.006 | ||

| gpd | YM | 0.95 (0.99) | (1.98 ± 0.07) × 107 | 95.3 | ||

| YM-olive oil | 0.89 (0.99) | (1.95 ± 0.09) × 107 | 89.2 | |||

| YM-oleic acid | 1.04 (0.98) | (2.44 ± 0.09) × 107 | 166.5 | |||

| YM-Tween 20 | 1.20 (0.99) | (2.11 ± 0.01) × 107 | 88.7 |

The log of the ratio of the corrected fluorescence intensity of the competitor PCR product to that of the target PCR product was plotted against the log of the copy numbers of competitor originally added. These plots were linear, and the slopes and correlation coefficients (r2) are shown.

The EP for each mRNA is the copy number of competitor DNA required at which the corrected fluorescence intensity of the competitor PCR product is equal to the measured intensity of the target PCR product. The values are averages from three independent experiments, and standard deviations are given.

The absolute copy numbers for each lip mRNA were normalized relative to the copy numbers of gpd mRNA before the fold induction or repression was calculated.

The fold induction of individual lip mRNA in YM was normalized to 1.

Relative amount is defined as the amount of individual mRNA relative to lip1 under each culture condition.

Expression of lip1 at 2.08 × 105 ± 0.02 × 105 molecules per μg of total RNA was observed when C. rugosa was cultured in YM, and the amount did not change after adding 1% olive oil or Tween 20. However, addition of oleic acid (1%) to the medium did reduce the number of lip1 transcripts by 44%. lip3 expressing 1.42 × 105 ± 0.03 × 105 molecules per μg of total RNA (68% of lip1 expression) was detected when C. rugosa was cultured in YM. When olive oil or oleic acid was added to the cultures, the lip3 transcripts increased by a significant 2.1-fold and 1.53-fold, respectively. In contrast, the lip3 transcripts decreased 12% when Tween 20 was added to the YM.

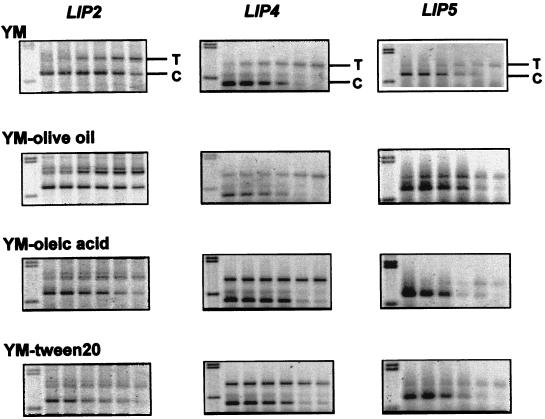

The levels of lip2, lip4, and lip5 were much lower (Fig. 5). Since the quantities of these three lip genes were too low to reach the plateau phase within 40 PCR cycles, it may not be possible to accurately quantitate them in regression plots. The EPs of various culture conditions in individual gene could be estimated from lanes with similar target/competitor ratios (Table 2). When C. rugosa was cultured in YM, the amounts of lip2, lip4, and lip5 expressed relative to lip1 were estimated to be 0.5, 0.1 and 0.4%, respectively. Olive oil also enhanced lip2, lip4, and lip5 expressions by about twofold, and oleic acid promoted the mRNA expression of lip4 and lip5 by four- and twofold, respectively. Only lip4 was highly induced by Tween 20, by a dramatic 7.9-fold.

FIG. 5.

Quantitation of lip2, lip4, and lip5 mRNAs by competitive RT-PCR. Twofold serial dilutions of the competitors (lanes 2 to 7) (0.032 to 0.001 amol for lip2 and lip5; 0.0128 to 0.0004 amol for lip4) (lane 1 contains a HindIII-digest of λ DNA as a size marker) were added to PCR mixtures containing a constant amount of cDNA generated from RNA isolated from C. rugosa cultured in YM, YM containing 1% olive oil, YM containing 1% oleic acid, or YM containing 1% Tween 20. After 40 cycles of amplification, the products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel stained with SYBR Green I. The gels were then scanned in the same way as in the experiment in Fig. 4 and quantitatively analyzed as described in the text. The positions of the corresponding target (T) and competitor (C) PCR products are indicated.

DISCUSSION

Studies on the differential expression of C. rugosa lip gene have been hampered by the difficulties of quantitation of individual mRNAs due to the highly related DNA sequences among this gene family. In the present study, we developed a sensitive and specific competitive RT-PCR method to quantitate the individual mRNA transcript of the five C. rugosa lip genes. The results demonstrated that the amount of lip transcripts follows the descending order of lip1, lip3, lip2, lip5, and lip4. lip1 and lip3 achieve higher expression, whereas expression of lip2, lip4, and lip5 is only 0.1 to 0.5% of the expression of lip1 transcript under YM culture conditions. These expression profiles are consistent with the findings that LIP1 and LIP3 are the major lipase proteins obtained by purification methods (9, 21, 36).

Lotti and Alberghina (25) suggested that C. rugosa constitutively produces LIP1 as the major isoform whereas expression of the other isoenzymes could be modulated according to the growth condition. Recently, Lotti et al. (28) hypothesized that lip genes might be subjected to different regulations. Some of them are constitutively expressed, and others are switched on by fatty acids. However, the DNA probe and antibody they used were nonspecific and were not sensitive enough to determine which members of the lip multigene family are in fact expressed under each condition at either the RNA or protein level. In this study, we have developed a sensitive and specific competitive RT-PCR method for precisely quantitating the steady-state levels of mRNAs for the different lipase genes. We showed that all the five lip genes are transcriptionally active and that different inducers may change the expression profile of individual genes. The constitutively expressed lip1 and lip3 showed few changes at the transcriptional level in various culture media, while suppression of lip1 by oleic acid and induction of lip3 by olive oil was demonstrated. Olive oil and oleic acid also promoted the expression of inducible lip2, lip4, and lip5 even in the presence of glucose, which previously was reported to be a repressing carbon source (28). Obviously, Tween 20 had a significant inducing effect on lip4 only. These results elucidate that the different lipase enzyme profiles under various culture conditions that we observed previously (5) were due to the differential expression of lip genes.

Previously, lipase isozymes purified from a commercial preparation (Lipase type VII [Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.]) were deduced to be products of different genes based on partial peptide sequencing (9, 36). However, LIP3, purified by Rúa et al. (36) as a major component of this lipase preparation, was not detected in any of the purified lipase preparations obtained by Diczfalusy et al. (9). This may be explained by our conclusion that the expression profile of C. rugosa lip genes can be altered by different culture conditions and even by batch-to-batch culture differences. We previously reported that different lipase isoforms from C. rugosa displayed quite different substrate specificities and thermostabilities (5, 39). Therefore, the production of different lipase isoforms in response to different growth conditions is physiologically important for C. rugosa, enabling it to grow on various substrates and in different environments. Traditionally, the culture conditions in fermentation are optimized for the maximal production of enzyme activity units. Our results indicate that quality is as important as quantity in enzyme preparations, since different culture conditions might result in production of heterogeneous compositions of the isozymes, which display different catalytic activities and specificities. By engineering the culture conditions, we can obtain enzyme preparations enriched in selected isozymes for particular biotechnological applications.

The multiplicity of genes encoding isozymes has been reported for many other yeast species (1, 3a, 16, 30, 31). The competitive RT-PCR method developed in this study can be used to examine the possible differential regulation of other yeast gene families (11, 20). The expression level of the mRNA transcript may be affected by many factors, such as promoter activity, upstream regulatory elements, and stability of the mRNA. Although elements such as the CAAT and TATAA boxes characteristic of eukaryotic promoters for transcriptional initiation have been found in the conserved regions upstream from the lip genes (26), we anticipate that transcriptional regulatory elements of C. rugosa lip promoters should be localized upstream from the conserved regions. Recently, nutrient-related transcriptional controlling elements have been identified in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (7). By assaying the β-galactosidase activities of promoter-lacZ fusions in S. cerevisiae, our unpublished data showed that the promoter activities of lip3 under various culture conditions were much higher than those of lip4 promoter. These findings suggest that the expression profile of lip genes could be accompanied by different regulation of the lip promoter activities. Studies of the transcriptional controlling elements of C. rugosa lip genes to further elaborate the mechanism of differential regulation of lip genes by various inducers are under way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants NSC-83-0409-B-019-008, NSC-85-0409-B-019-008, and NSC-87-2311-B-001-047 from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apel-Birkhold P C, Walton J D. Cloning, disruption, and expression of two endo-beta-1,4-xylanase genes, XYL2 and XYL3, from Cochliobolus carbonum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4129–4135. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4129-4135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton M J, Hamman J P, Fichter K C, Calton C J. Enzymatic resolution of (R,S)-2-(4-hydroxyphenoxy) propionic acid. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1990;12:577–583. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker-André M, Hahlbrock K. Absolute mRNA quantification using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A novel approach by a PCR aided transcript titration assay (PATTY) Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9437–9446. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Bertolini M C, Laramée L, Thomas D Y, Cygler M, Schrag J D, Vernet T. Polymorphism in the lipase genes of Geotrichum candidum strains. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brahimi-Horn M C, Guglielmino M L, Elling L, Sparrow L G. The esterase profile of a lipase from Candida cylindracea. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1042:51–54. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang R C, Chou S J, Shaw J F. Multiple forms and functions of Candida rugosa lipase. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 1994;19:93–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chirgwin J M, Przybyla A E, McDonald R J, Rutter W J. Isolation of biological active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi J Y, Stukey J, Hwang S Y, Martin C E. Regulatory elements that control transcription activation and unsaturated fatty acid-mediated repression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae OLE1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3581–3589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.7.3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diczfalusy M A, Hellman U, Alexson S E H. Isolation of carboxylester lipase (CEL) isoenzymes from Candida rugosa and identification of the corresponding genes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;348:1–8. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi N N. Applications of lipase. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1997;74:621–634. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gettemy J M, Ma B, Alic M, Gold M H. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis of the regulation of the manganese peroxidase gene family. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:569–574. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.569-574.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilliand G, Perrin S, Blanchard K, Bunn H F. Analysis of cytokine mRNA and DNA: detection and quantitation by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2725–2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordillo M A, Obradors N, Montesinos J L, Valero F, Lafuente F J, Solà C. Stability studies and effect of the initial oleic acid concentration on lipase production by Candida rugosa. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:38–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00170620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harwood J. The versatility of lipase for industrial uses. Trends Biochem Sci. 1989;14:125–126. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins J D. A survey on intron and exon lengths. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9893–9908. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.9893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hube B, Monod M, Schofield D A, Brown A J P, Gow N A R. Expression of seven members of the gene family encoding secretory aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huge-Jensen B, Galluzzo D R, Jensen R G. Partial purification and characterization of free and immobilized lipases from Mucor miehei. Lipids. 1987;22:559–565. doi: 10.1007/BF02537281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwai M, Tsujisaka Y. The purification and the properties of three kinds of lipases from Rhizopus delemer. Agric Biol Chem. 1974;38:1241–1247. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwai M, Okumura S, Tsujisaka Y. The comparison of the properties of two lipases from Penicillium cyclopium Westring. Agric Biol Chem. 1975;39:1063–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janse B J H, Gaskell J, Akhtar M, Cullen D. Expression of Phanerochaete chrysosporium genes encoding lignin peroxidases, manganese peroxidases, and glyoxal oxidase in wood. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3536–3538. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.9.3536-3538.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawaguchi Y, Honda H, Taniguchi-Morimura J, Iwasaki S. The codon CUG is read as serine in an asporogenic yeast Candida cylindracea. Nature. 1989;341:164–166. doi: 10.1038/341164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klibanov A M. Asymmetric transformations catalyzed in organic solvents. Acc Chem Res. 1990;23:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Köhrer K, Domdey H. Preparation of high molecular weight RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:398–405. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longhi S, Fusetti F, Grandori R, Lotti M, Vanoni M, Alberghina L. Cloning and nucleotide sequences of two Lip genes from Candida cylindracea. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1131:227–232. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90085-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lotti M, Alberghina L. Candida rugosa lipase isozymes: cloning, sequencing, analysis of the substrate binding pocket. In: Malcata F X, editor. Engineering of/with Lipases. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lotti M, Grandori R, Fusetti F, Longhi S, Brocca S, Tramontano A, Alberghina L. Molecular cloning and analysis of Candida cylindracea lipase sequences. Gene. 1993;124:45–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90760-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lotti M, Tramontano A, Longhi S, Fusetti F, Brocca S, Pizzi E, Alberghina L. Variability within the Candida rugosa lipases family. Protein Eng. 1994;7:531–535. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lotti M, Monticelli S, Montesinos J L, Brocca S, Valero F, Lafuente J. Physiological control on the expression and secretion of Candida rugosa lipase. Chem Phys Lipids. 1998;93:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(98)00038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macrae A R. Lipase-catalyzed interesterification of oils and fats. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1983;60:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mansur M, Suarez T, Fernandez-Larrea J B, Brizuela M A, Gonzalez A E. Identification of a laccase gene family in the new lignin-degrading basidiomycete CECT 20197. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2637–2646. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2637-2646.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monod M, Togni G, Hube B, Sanglard D. Multiplicity of genes encoding secreted aspartic proteinases in Candida species. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:357–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patkar S A, Bjørkling F, Zundel M, Schulein M, Svendsen A, Heldt-Hansen H P, Gormsen E. Purification of two lipases from Candida antarctica and their inhibition by various inhibitors. Ind J Chem. 1993;32B:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piatak M, Jr, Luk K C, Williams B, Lifson J D. Quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction for accurate quantitation of HIV DNA and RNA species. BioTechniques. 1993;14:70–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raeymaekers L. Quantitative PCR: theoretical considerations with practical implications. Anal Biochem. 1993;214:582–585. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raeymaekers L. A commentary on the practical applications of competitive PCR. Genome Res. 1995;5:91–94. doi: 10.1101/gr.5.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rúa M L, Diaz-Maurino T, Fernandez V M, Otero C, Ballesteros A. Purification and characterization of two distinct lipases from Candida cylindracea. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1156:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(93)90134-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabuquillo P, Reina J, Fernandez-Lorente G, Guisan J M, Fernandez-Lafuente R. ‘Interfacial affinity chromatography’ of lipases: separation of different fractions by selective adsorption on supports activated with hydrophobic groups. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1388:337–348. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw J F, Chang C H, Wang Y J. Characterization of three distinct forms of lipolytic enzymes in a commercial Candida lipase. Biotechnol Lett. 1989;11:779–784. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaw J F, Chang R C, Wang F F, Wang Y J. Lipolytic activities of lipase immobilized on six support materials. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1990;35:132–137. doi: 10.1002/bit.260350204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siebert P D, Larrick J W. Competitive PCR. Nature. 1992;359:557–558. doi: 10.1038/359557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valero F, Del Río J L, Poch M, Solà C. Fermentation behaviour of lipase production by Candida rugosa growing on different mixtures of glucose and olive oil. J Ferment Bioeng. 1991;72:399–401. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vulfson E N. Industrial applications of lipases. In: Woolley P, Petersen S B, editors. Lipases—their structure, biochemistry and application. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1994. pp. 271–288. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y J, Sheu J Y, Wang F F, Shaw J F. The lipase catalyzed oil hydrolysis in the absence of added emulsifier. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1988;31:628–633. doi: 10.1002/bit.260310618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]