Abstract

The marine bacterium Shewanella algae, which was identified as the cause of human cases of bacteremia and ear infections in Denmark in the summers of 1994 and 1995, was detected in seawater only during the months (July, August, September, and October) when the water temperature was above 13°C. The bacterium is a typical mesophilic organism, and model experiments were conducted to elucidate the fate of the organism under cold and nutrient-limited conditions. The culturable count of S. algae decreased rapidly from 107 CFU/ml to 101 CFU/ml in approximately 1 month when cells grown at 20 to 37°C were exposed to cold (2°C) seawater. In contrast, the culturable count of cells exposed to warmer seawater (10 to 25°C) remained constant. Allowing the bacterium a transition period in seawater at 20°C before exposure to the 2°C seawater resulted in 100% survival over a period of 1 to 2 months. The cold protection offered by this transition (starvation) probably explains the ability of the organism to persist in Danish seawater despite very low (0 to 1°C) winter water temperatures. The culturable counts of samples kept at 2°C increased to 105 to 107 CFU/ml at room temperature. Most probable number analysis showed this result to be due to regrowth rather than resuscitation. It was hypothesized that S. algae would survive cold exposure better if in the biofilm state; however, culturable counts from S. algae biofilms decreased as rapidly as did counts of planktonic cells.

Shewanella algae is a mesophilic marine bacterium and is a recently defined species closely related to the more psychrotolerant Shewanella putrefaciens (13). Strains of S. algae probably play an important role in the environment, e.g., in the turnover of inorganic material, since the organism is capable of reducing Fe(III) in anaerobic respiration (4, 36). S. algae may cause disease in humans (11, 19, 29); it has been implicated in cases of ear and wound infections, bacteremia, and sepsis. Strains identified as S. putrefaciens have been isolated from a number of clinical cases; however, the isolates may have been misidentified and may rightly belong to S. algae (13). By traditional phenotypic characterization methods, including API 20NE, S. algae is identified as S. putrefaciens. S. algae can be differentiated from S. putrefaciens by its ability to grow at 42°C and in 10% NaCl and its inability to grow at 4°C. Also, its G+C content is 52 to 55%; that of S. putrefaciens is 43 to 47% (13).

Since S. algae was originally isolated from the marine environment, it has been suggested that this environment is the source of the organism in diseased humans (11, 14); patients have often reported contact with seawater before infection. In support of this hypothesis, no significant difference has been found between clinical and water isolates of S. algae, as assessed by whole-cell protein profiling, ribotyping, and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis (14). S. algae is a typical mesophilic bacterium and does not normally grow at temperatures below 5°C. Infections by mesophilic marine bacteria are not common in Denmark, but the unusually warm summer in 1994 resulted in S. algae infections (11, 19) as well as infections caused by other mesophilic marine bacteria, such as Vibrio vulnificus (7).

Because S. algae occurs in marine waters and is a mesophilic organism, it must survive many months of low water temperatures during winter. The organism must also be able to cope with extended periods of low nutrient and energy availability. Many bacteria undergo a so-called starvation survival response under oligotrophic conditions (27). Several starvation proteins are expressed (15, 33), and these proteins may offer cross-protection against other stress factors, such as low temperatures. Thus, the mesophilic marine bacterium V. vulnificus remains culturable for a significantly longer period if starved before exposure to low temperatures (35).

While the starvation survival response is widely recognized as a mechanism of survival, more controversy exists with regard to the viable but nonculturable (VBNC) concept (25). In this state, which is stress induced, the bacteria are unable to grow on laboratory media but remain alive, as visualized by DNA staining procedures. When the stressful conditions are reversed, the bacteria regain the ability to grow on laboratory media. Much debate exists as to whether this behavior is due to true resuscitation of the nonculturable bacteria from a dormant state (31, 40) or whether the VBNC cells are indeed moribund and “resuscitation” is a result of regrowth of a few surviving cells (12, 23, 39).

The ecology of S. algae in the marine environment has not been studied before, and the purpose of the present study was to determine the occurrence of S. algae in Danish seawater. As expected, S. algae was not detected during the colder months. Model experiments were therefore conducted to study the fate of the organism under cold and nutrient-limited conditions. It has been suggested that adhesion to surfaces offers another survival strategy for starved bacteria in the aquatic environment (8). Also, bacteria that adhere and form biofilms are in general more resistant to adverse conditions (6). We therefore also investigated the survival in seawater of S. algae in the biofilm state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and investigation of samples.

Ten 200-ml water samples were collected every second month from September 1996 to October 1997 at Køge Bugt, approximately 20 km south of Copenhagen. The seawater temperature was measured with a digital thermometer (Testo 110; Testo GmbH & Co., Lenzkirch, Germany). Since no specific method exists for the enumeration of S. algae, water samples were plated in a medium used for detection of hydrogen sulfide production. Strains were randomly isolated from black (H2S-producing) colonies and identified (see below). Seawater samples were serially diluted in physiological saline, and viable counts were estimated by pour plating in iron agar (Oxoid CM964 [16]). Thiosulfate, l-cysteine, and ferric citrate were added to the agar, and hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria appeared as black colonies in the agar due to the precipitation of FeS. Two sets of plates were prepared from each sample; one set was incubated at 4°C for 14 days to enumerate S. putrefaciens, and one set was incubated at 37°C for 2 days to enumerate S. algae. The medium contains no selective agent, so other hydrogen sulfide producers, e.g., Vibrio spp., will also form black colonies.

Isolation and identification of S. algae.

From each of the 10 samples, four black colonies were isolated from iron agar plates at 4 and 37°C, yielding a total of 80 H2S-producing bacteria per sampling point. The isolates were pure cultured on iron agar plates and tested for glucose metabolism in Hugh-Leifson medium (19). Fermentative strains were likely to be members of the Vibrionaceae or the Enterobacteriaceae. Strains which were not fermentative were further identified by testing for the Gram stain reaction in 3% KOH (17), the oxidase reaction (24), shape, and motility. Strains reducing trimethylamine oxide and producing H2S were classified as Shewanella spp. (16). Differentiation between S. algae and S. putrefaciens was done by testing for growth in 6 and 10% NaCl at 25°C and at 4 and 42°C (with 0.5% NaCl) as described by Fonnesbech Vogel et al. (13). Most of the strains isolated from plates incubated at 37°C were tested for G+C content (13, 26). A number of strains (September 1997) could not be directly differentiated by their temperature or NaCl growth profile and were further tested with the API 20NE (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Survival of S. algae planktonic cells in seawater.

A strain of S. algae isolated from a patient with bacteremia (11) was grown in tryptone soya broth (TSB; Oxoid CM129) at 37 or 20°C for 2 days. Cells from 10 ml were harvested (5,000 × g for 10 min) and resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Seawater was collected at Køge Bugt and left in the refrigerator for 3 to 4 days before being autoclaved in portions of 200 ml. After being cooled to an appropriate temperature (2, 10, or 25°C), the seawater was inoculated with an S. algae suspension, yielding an initial cell density of approximately 107 CFU/ml. Samples were withdrawn weekly for the determination of culturable counts by spread plating on iron agar. In samples with low viable counts, total counts were estimated by 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Briefly, samples were filtered through black 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters (MicronKlear K02BP02500; MSI) supported by Whatman GF/C glass microfiber filters (Whatman, Maidstone, United Kingdom) and stained with 10 μg of DAPI solution per ml. Filters were mounted with paraffin oil, and counts were determined by use of an Olympus BH2 fluorescence microscope with a 320- to 400-nm excitation filter and a >420-nm barrier filter. In one experiment, seawater inoculated with S. algae was kept at 20°C for 2 weeks before transfer and exposure to 2°C.

Resuscitation of S. algae planktonic cells.

S. algae cells having been exposed to a low temperature were allowed to resuscitate by transfer to 25°C. The contents of flasks in which the counts had decreased 5 log units or more were serially diluted in 2°C cold seawater. The flasks and the dilution series were kept at 25°C for 2 days. Culturable counts in the flasks and in each dilution were then determined by serial dilution and surface plating on iron agar. By the initial dilution in cold seawater, an attempt was made to avoid the nutrient and temperature shock that cells would experience if plated directly on iron agar. If a large fraction of the population were able to resuscitate, then culturable bacteria should be found in several of the higher dilutions.

Survival of S. algae biofilm cells in seawater.

Stainless steel plates (1 by 2 cm2) were thoroughly cleaned (with detergent and acetone) and placed in a holder ensuring a vertical position. The holder was placed in a beaker and sterilized. The plates were covered with 150 ml of TSB, and the medium was inoculated with S. algae precultured for 24 h in TSB at 20°C. A magnetic stirrer ensured circulation at 150 rpm. The plates were incubated for 4 days at room temperature. After being washed for 2 min in PBS, the plates were individually transferred to tubes with 4 ml of sterile seawater tempered at either 2 or 20°C. Each week, plates were removed for enumeration of cells by use of an indirect conductance measurement with a Malthus instrument (22). Briefly, the stainless steel plates with bacterial biofilms were placed in tubes with 3 ml of TSB. Electrodes were places in an inner tube filled with 0.5 ml of 0.1 N NaOH, and the tubes were incubated in a Malthus water bath at 25°C. CO2 evolving from the respiring cells was absorbed by the NaOH solution, and this neutralization caused a decrease in conductance. The time taken from the start of the measurement until a significant change occurred (detection time) was inversely correlated with the initial number of bacteria. A standard curve relating the detection time to colony counts was prepared from a 10-fold serial dilution of 24-h S. algae cells in solution from a biofilm experiment. Biofilm plates were sampled in duplicate.

RESULTS

Occurrence of S. algae in Danish seawater.

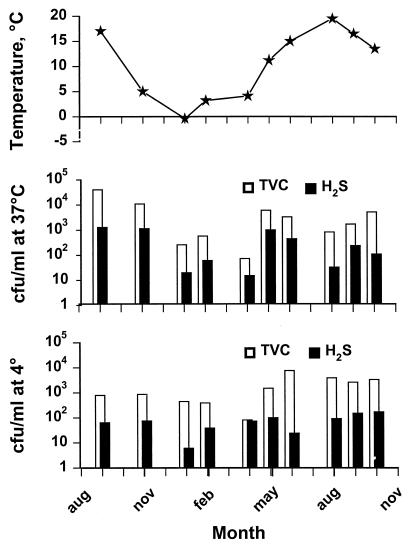

The water temperature at Køge Bugt varied from −0.4°C in January 1997 to 19.5°C in August 1997 (Fig. 1). Total counts on iron agar plates incubated at 4°C were about 103 CFU/ml (from 70 to 5,200 CFU/ml), of which approximately 10% were H2S producing (Fig. 1). The total counts at 37°C were not significantly different from the counts at 4°C, and the number of H2S-producing organisms was approximately 1 log unit lower. The lowest counts were observed when the water temperature was between 0 and 4°C.

FIG. 1.

Changes in water temperature and bacterial levels in waters of Køge Bugt from September 1996 to October 1997. TVC, total viable count on iron agar; H2S, hydrogen sulfide producers on iron agar.

Of the 40 H2S-producing organisms isolated at each sampling point from plates incubated at 37°C, various numbers were assumed to be Shewanella spp. based on their nonfermentative reactions (Table 1). Such presumptive Shewanella spp. were isolated in all but one month, but no systematic pattern could be observed in the fluctuations (Table 1). All strains were gram-negative, motile rods with positive oxidase and catalase reactions, and all reduced trimethylamine oxide and produced H2S; these characteristics identified them as Shewanella spp. In the colder months, most of the nonfermentative bacteria isolated from plates incubated at 37°C were capable of growing at 4°C and in the presence of 6% NaCl. Some strains grew, albeit slowly, at 42°C (Table 1), at which temperature growth was detected in 7 to 14 days. The G+C contents of these strains varied from 44 to 48%; this characteristic identified them as S. putrefaciens. In contrast, 47 strains isolated in September 1996 and August 1997 and 2 strains isolated in October 1997 grew rapidly in 10% NaCl and at 42°C but could not grow at 4°C. All of these strains but one (from August 1997) had G+C contents of 53 to 54% and were identified as S. algae. Thirteen H2S-producing nonfermentative strains isolated in September 1997 were identified as Shewanella but did not grow at 4 or 42°C. They had G+C contents of 46.5 to 49%. These strains were tested with the API 20NE and assimilated glucose, N-acetylglucosamine, maltose, caprate, and maltose but not adipate or citrate. These reactions are similar to those of genomic group III of mesophilic S. putrefaciens (34), as characterized by Ziemke et al. (41). All strains isolated at 4°C were identified as S. putrefaciens. Although some strains isolated in August and September grew slowly at 42°C and/or in 10% NaCl, all had G+C contents of 45 to 48% (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Characterization of nonfermentative hydrogen sulfide-producing bacteria isolated from Danish seawater in 1996 to 1997a

| Yr | Month | No. of nonfermentative strainsb | No. of strains growing at or in:

|

No of strains tested for G+C content | G+C content (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | 42°C | 10% NaCl | |||||

| 1996 | September | 29 | 0 | 21 | 27 | 25 | 52.7–55.0 |

| September | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 48.3c | |

| November | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 47.3 | |

| 1997 | January | 20 | 20 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 45.8–47.4 |

| February | 25 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 44.7–48.2 | |

| April | 32 | 32 | 2 | 0 | 32 | 44.7–47.3 | |

| May | 0 | ||||||

| June | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 47.2 | |

| August | 19 | 1 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 52.4–54.8 | |

| August | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 43.8 | |

| September | 13 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 46.5–49.0d | |

| October | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 52.9–57.8 | |

Strains were isolated from iron agar plates incubated at 37°C for 2 days.

A total of 40 H2S-producing bacterial strains were isolated from iron agar plates incubated at 37°C at each sampling point. All nonfermentative strains were identified as Shewanella spp.

This value is from a strain not growing at 42°C or in 10% NaCl.

Survival and resuscitation of planktonic S. algae in seawater.

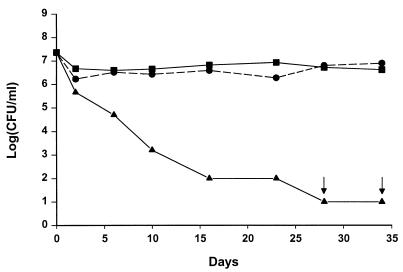

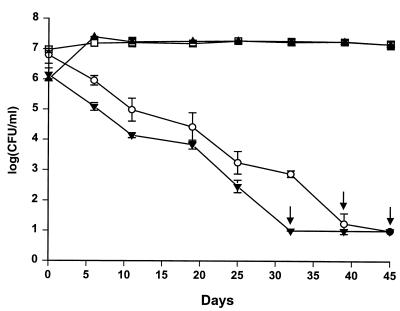

The culturable count of S. algae remained almost constant when cells were exposed to seawater at 10 to 25°C (Fig. 2). The cells changed from a rod shape of approximately 1 by 3 μm to a smaller coccal shape, as assessed by phase-contrast microscopy (data not shown). At 2°C, the culturable count decreased from 107 CFU/ml to 101 to 102 CFU/ml in 4 to 5 weeks (Fig. 2 and 3). Even when the count decreased below 102 CFU/ml, cells at a level of approximately 105 CFU/ml could still be detected by DAPI staining (data not shown). When S. algae cells were exposed to seawater at 20°C before transfer to 2°C, the culturable count remained at 107 CFU/ml for more than 6 weeks (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Changes in culturable counts of S. algae precultured at 37°C and exposed to sterile seawater at 2°C (▴), 10°C (●), or 25°C (■). Arrows indicate counts below the detection limit of 10 CFU/ml.

FIG. 3.

Changes in culturable counts of S. algae precultured at 37 or 20°C and exposed to sterile seawater at 2°C with or without a transition period in seawater at 20°C. Symbols: □ and ○, S. algae cultured at 20°C; ▴ and ▾, S. algae cultured at 37°C; □ and ▴, exposure to sterile 20°C seawater for 14 days before exposure to 2°C; ○ and ▾, exposure to 2°C seawater. Arrows indicate counts below the detection limit of 10 CFU/ml. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Samples in which the culturable count of S. algae had decreased as a result of a low temperature were shifted to 25°C, and the culturable count increased to 107 CFU/ml. Depending on the count before the temperature upshift, culturable cells were also detected in the 1:10 or 1:100 dilution at a level of 107 CFU/ml. Culturable cells were never detected in higher dilutions.

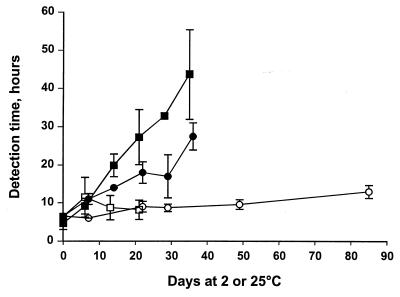

Survival of biofilm S. algae in seawater.

S. algae readily formed biofilms on stainless steel when grown in TSB. Based on a standard curve relating detection times to colony counts, the number of cells on the plates after 4 days was estimated to be 1.5 × 107 CFU, corresponding to 4 × 106 CFU/cm2. The detection time increased rapidly when plates were exposed to 2°C (Fig. 4), indicating a decrease in the culturable count that was even more rapid than when planktonic cells were exposed to a low temperature. Exposure of biofilms to 25°C caused only a minor reduction in the culturable count, as measured by the detection time (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Changes in conductometric detection times (indicating culturable counts) of biofilms of S. algae exposed to chilled (2°C) or temperate (25°C) seawater. Data are from two separate experiments (experiment 1, 2°C [■] and 25°C [□]; experiment 2, 2°C [●] and 25°C [○]). Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

S. algae could be readily isolated from Danish coastal waters, and its presence correlated with water temperature in that the organism could not be detected during cold winter and spring months (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Similar findings have been reported for other mesophilic marine bacteria, such as V. vulnificus (18, 28, 32) and Vibrio parahaemolyticus (2, 9), for which the levels in seawater correlate with water temperature. Our study and the study by Høi et al. (18) both assessed the occurrence of mesophilic marine bacteria in Danish waters. Other studies have also evaluated the presence of vibrios in waters with a large yearly temperature fluctuation, such as the Elbe River in Hamburg (2) and Dutch coastal waters (38). Although the winter water temperatures in the Danish, German, and Dutch studies are significantly lower (approximately 0°C) than the lowest temperatures reported in similar incidence studies (9, 28, 32), the levels of approximately 10 to 100 CFU/ml reached during the warm months are equivalent to the levels reached in environments in which the minimum temperatures are significantly higher. These results could indicate that nutrient availability rather than minimum water temperature is important in determining maximum numbers.

The isolation of S. putrefaciens during the cold winter months from plates incubated at 37°C confirmed earlier findings (13) that within this heterogenous psychrotolerant group, strains tolerating the highest temperature (37°C) and a NaCl concentration of 6% have higher G+C contents (46 to 48% versus 43 to 44%) than strains not growing at high temperatures, e.g., strains isolated from spoiling iced fish (13).

In a study of S. algae BrY, a size reduction from 2.2 to 1 μm over 5 to 9 weeks was seen when the bacterium was exposed to sterile PBS at room temperature (5). We similarly found that the exposure of S. algae to sterile seawater led to a size reduction. Such a response to starvation has been found for many other bacteria (21, 27). The exposure of S. algae to sterile seawater resulted in two separate culturable count curves, depending on temperature (Fig. 2). These findings are similar to the results obtained for V. vulnificus, for which culturable counts remained almost constant during starvation at room temperature but decreased rapidly (in 5 to 15 days) when cells were exposed to cold water (12, 39). In other studies, V. vulnificus biotype 2 (1) and V. parahaemolyticus (21) behaved in a similar manner, although the decrease in culturable counts at a low temperature was somewhat slower. Rapid (within hours) temperature downshifts are rarely encountered by bacteria in nature, where they pass through slower temperature changes. Mimicking this situation by allowing S. algae a transition period in 20°C seawater before cold exposure markedly increased its ability to remain culturable (Fig. 3). Also, V. vulnificus remained culturable at a low temperature for longer periods when starved before cold exposure (35, 39). Despite the starvation periods that S. algae must encounter in nature, the culturable count decreased in natural seawater (Fig. 1). Other factors, such as grazing or phage attack, may limit or reduce the population in nature.

Bacteria in the marine environment are associated mostly with surfaces rather than being in the planktonic state. When grown in TSB, S. algae formed a multilayered biofilm on stainless steel surfaces in just a few days. This result was expected, as the organism in other niches is part of biofilm communities, e.g., in activated sludge (5). A crude oil bacterium, “Pseudomonas sp.” (strain 200) (30), later identified as S. putrefaciens (10), did not form any significant biofilm on stainless steel coupons in 2 weeks, but a thick bacterial layer was seen after 9 weeks. Thick fibrous exopolysaccharide material entrapped the cells (30). We have seen that S. algae will form a surface layer of slimy growth 1 to 2 mm thick after only 3 to 4 days in nutrient broth at room temperature, indicating that exopolysaccharides required for biofilm formation are indeed readily produced. Since bacteria forming a biofilm are believed to be more resistant to a number of adverse conditions (6), we hypothesized that surface-adherent S. algae would remain culturable at a low temperature for longer periods than planktonic cells. However, our results (Fig. 4) did not support this hypothesis. The Malthus method proved suitable for estimating culturable counts of bacteria adhering to surfaces. However, prolonged lag phases will, due to conversion via a standard curve, result in lower culturable count equivalents than are actually present. This factor should be kept in mind when one is attempting to translate detection times to culturable cells.

The culturable count of mesophilic bacterial cells generally decreases when the cells are exposed to adverse conditions, such as cold temperature, and increases when conditions become favorable, e.g., the temperature is raised (12, 39, 40). Some authors believe that this response is due to true resuscitation of the VBNC part of the population (21, 37, 40), whereas others have found that the phenomenon is due to regrowth of a few surviving cells (3, 12). As pointed out by Kell et al. (23), the majority of studies reporting resuscitation have not eliminated the possibility of regrowth by using an appropriate experimental design. Using a simple most-probable-number-based approach (39), we found that the return of S. algae to culturability was more likely caused by regrowth of a few surviving cells than by resuscitation.

In conclusion, S. algae behaves similarly to other mesophilic marine bacteria when exposed to oligotrophic conditions. The increase in the culturable count when cold, “nonculturable” cells are returned to a warm temperature is likely to be explained by regrowth rather than resuscitation. The occurrence in Danish waters of S. algae is therefore probably due to the prolonged survival in cold water of starved cells at very low levels and subsequent regrowth when the water temperature increases. We could not confirm our hypothesis that biofilm cells are more resistant to cold oligotrophic conditions than planktonic cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partly financed by the Danish Food Technology Programme (FØTEK II).

The assistance of Lars Ravn and Christiane Buch is appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biosca E G, Amaro C, Marco-Noales E, Oliver J D. Effect of low temperature on starvation survival of eel pathogen Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:450–455. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.450-455.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bockemühl J, Roch K, Wohlers B, Aleksic V, Aleksic S, Wokatsch R. Seasonal distribution of facultatively enteropathogenic vibrios (Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio mimicus, Vibrio parahaemolyticus) in the freshwater of the Elbe River at Hamburg. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;60:435–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb05089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogosian G, Morris P L, O’Neil J P. A mixed-culture recovery method indicates that enteric bacteria do not enter the viable but nonculturable state. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1736–1742. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1736-1742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caccavo F, Jr, Blakemore R P, Lovley D R. A hydrogen-oxidizing Fe(III)-reducing microorganism from the Great Bay estuary, New Hampshire. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3211–3216. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3211-3216.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caccavo F, Jr, Ramsing N B, Costerton W. Morphological and metabolic responses to starvation by the dissimilatory metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella alga BrY. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4678–4682. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.12.4678-4682.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costerton J W, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell D E, Korber D R, Lappin-Scott H M. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalsgaard A, Frimodt-Møller N, Bruun B, Høi L, Larsen J L. Clinical manifestations and epidemiology of Vibrio vulnificus infections in Denmark. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:227–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01591359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson M P, Humphrey B, Marshall K C. Adhesion: a tactic in the survival strategy of a marine vibrio during starvation. Curr Microbiol. 1981;6:195–198. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DePaola A, Hopkins L H, Peeler J T, Wentz B, McPhearson R M. Incidence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in U.S. coastal waters and oysters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2299–2302. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2299-2302.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiChristina T J, DeLong E F. Design and application of rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for the dissimilatory iron- and manganese-reducing bacterium Shewanella putrefaciens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4152–4160. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4152-4160.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domínguez H, Fonnesbech Vogel B, Gram L, Hoffmann S, Schæbel S. Shewanella alga bacteremia in two patients with lower leg ulcers. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:1036–1039. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firth J R, Diaper J P, Edwards C. Survival and viability of Vibrio vulnificus in seawater monitored by flow cytometry. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1994;18:268–271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fonnesbech Vogel B, Jørgensen K, Christensen H, Olsen J E, Gram L. Differentiation of Shewanella putrefaciens and Shewanella alga using ribotyping, whole-cell protein profiles, phenotypic characterization, and 16S rRNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2189–2199. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2189-2199.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonnesbech Vogel, B., H. M. Holt, P. Gerner-Smidt, A. Bundvad, P. Søgaard, and L. Gram. Homogeneity and type differences among environmental and clinical isolates of Shewanella algae. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Givskov M, Eberl L, Molin S. Responses to nutrient starvation in Pseudomonas putida KT2442: two-dimensional electrophoretic analysis of starvation- and stress-induced proteins. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4816–4824. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.4816-4824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gram L, Trolle G, Huss H H. Detection of specific spoilage bacteria from fish stored at low (0°C) and high (20°C) temperatures. Int J Food Microbiol. 1987;4:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregersen T. Rapid method for the distinction of Gram-negative bacteria from Gram-positive bacteria. Eur J Appl Microbiol. 1978;5:123–127. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Høi L, Larsen J L, Dalsgaard I, Dalsgaard A. Occurrence of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes in Danish marine environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:7–13. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.7-13.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt H M, Søgaard P, Gahrn-Hansen B. Ear infections with Shewanella alga. A bacteriologic, clinical and epidemiological study of 67 cases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:329–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hugh R, Leifson E. The taxonomic significance of fermentative versus oxidative gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1953;66:24–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.66.1.24-26.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang X, Chai T-J. Survival of Vibrio parahaemolyticus at low temperatures under starvation conditions and subsequent resuscitation of viable, nonculturable cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1300–1305. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1300-1305.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johansen C, Falholt P, Gram L. Enzymatic removal and inactivation of bacterial biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;63:3724–3728. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3724-3728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kell D B, Kaprelyants A S, Weichart D H, Harwood C R, Barer M R. Viability and activity in readily culturable bacteria: a review and discussion of the practical issues. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1998;73:169–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1000664013047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs N. Identification of Pseudomonas pyocyanae by the oxidase reaction. Nature. 1956;178:703. doi: 10.1038/178703a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDougald D, Rice S A, Weichart D, Kjelleberg S. Nonculturability: adaptation or debilitation? FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mesbah M, Premachandran U, Whitman W B. Precise measurement of the G + C content of deoxyribonucleic acid by high-performance liquid chromatography. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1989;39:159–167. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morita R Y. Bacteria in oligotrophic environments. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motes M L, DePaola A, Cook D W, Veazey J E, Hunsucker J C, Garthright W E, Blodgett R J, Chirtel S J. Influence of water temperature and salinity on Vibrio vulnificus in Northern Gulf and Atlantic Coast oysters (Crassostrea virginica) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1459–1465. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1459-1465.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nozue H, Hayashi T, Hashimoto Y, Ezaki T, Hamasaki K, Ohwada K, Terawaki Y. Isolation and characterization of Shewanella alga from human clinical specimens and emendation of the description of S. alga Simidu et al., 1990, 335. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:628–634. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-4-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obuekwe C O, Westlake D W S, Cook F D, Costerton J W. Surface changes in mild steel coupons from the action of corrosion-causing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:766–774. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.3.766-774.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliver J D, Hite F, McDougald D, Andon N L, Simpson L M. Entry into, and resuscitation from, the viable but nonculturable state by Vibrio vulnificus in an estuarine environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2620–2623. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2624-2630.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Neill K R, Jones S H, Grimes D J. Seasonal incidence of Vibrio vulnificus in the Great Bay estuary of New Hampshire and Maine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3257–3262. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3257-3262.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Östling J, Holmquist L, Flärdh K, Svenblad B, Jouper-Jaan Å, Kjelleberg S. Starvation and recovery of Vibrio. In: Kjelleberg S, editor. Starvation in bacteria. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owen R J, Legros R M, Lapage S P. Base composition, size and sequence similarities of genome deoxyribonucleic acids from clinical isolates of Pseudomonas putrefaciens. J Gen Microbiol. 1978;104:127–138. doi: 10.1099/00221287-104-1-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paludan-Müller C, Weichart D, McDougald D, Kjelleberg S. Analysis of starvation conditions that allow for prolonged culturability of Vibrio vulnificus at low temperature. Microbiology. 1996;142:1675–1684. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosello-Mora R, Caccavo F, Jr, Springer N, Spring S, Osterlehner K, Shuler D, Ludwig W, Amann R, Schleifer K H. Isolation and taxonomic characterization of a halotolerant facultatively iron-reducing bacterium. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1994;17:569–573. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinert M, Emödy L, Amann R, Hacker J. Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2047–2053. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.2047-2053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veenstra J, Rietra P J G M, Coster N M, Slaats E, Dirk-Go S. Seasonal variations in the occurrence of Vibrio vulnificus along the Dutch coast. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:285–290. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weichart D, Oliver J D, Kjelleberg S. Low temperature induced non-culturability and killing of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiteside M D, Oliver J D. Resuscitation of Vibrio vulnificus from the viable but nonculturable state. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1002–1005. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1002-1005.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziemke F, Höfle M G, Lalucat J, Roselló-Mora R. Reclassification of Shewanella putrefaciens Owen’s genomic group II as Shewanella baltica sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:179–186. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-1-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]