Abstract

Background:

Thirty per cent supramolecular salicylic acid (SSA) is a water-soluble, sustained release salicylic acid (SA) modality, which is well tolerated by sensitive skin. Anti-inflammatory therapy plays an important role in papulopustular rosacea (PPR) treatment. SSA at a 30% concentration has a natural antiinflammatory property.

Aims:

This study aims to investigate the efficacy and safety of 30% SSA peeling for PPR treatment.

Methods:

Sixty PPR patients were randomly divided into two groups: SSA group (30 cases) and control group (30 cases). Patients of the SSA group were treated with 30% SSA peeling three times every 3 weeks. Patients in both groups were instructed to topically apply 0.75% metronidazole gel twice daily. Transdermal water loss (TEWL), skin hydration and erythema index were assessed after 9 weeks.

Results:

Fifty-eight patients completed the study. The improvement of erythema index in the SSA group was significantly better than that in the control group. No significant difference was found in terms of TEWL between the two groups. The content of skin hydration in both the groups increased, but there was no statistical significance. No severe adverse events were observed in both the groups.

Conclusion:

SSA can significantly improve the erythema index and overall appearance of skin in rosacea patients. It has a good therapeutic effect, good tolerance and high safety.

KEY WORDS: Erythema, metronidazole, papulopustular rosacea, supramolecular salicylic acid

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder which can be divided into four subtypes: ocular, phymatous, erythematotelangiectatic and papulopustular.[1] Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is a common clinical subtype of rosacea, which is characterised by persistent papulopustules and erythema.[2,3] The specific pathophysiology of PPR has not been fully unfolded, and several reports indicated that inflammatory and vascular changes might contribute to PPR.[4] Oral antibiotics, topical azelaic acid and metronidazole are believed to be common treatments for PPR. However, the treatment of PPR is challenging due to its recurrence.

Salicylic acid (SA) is a member of hydroxyl acid compounds with anti-inflammatory and broad-spectrum antibacterial properties. SA has been widely used to treat several skin disorders including lentigines, melisma and vulgaris as a peeling agent.[5,6] However, several studies reported that SA might cause some side effects such as temporary crusting, intense exfoliation, dryness and prolonged erythema, especially in sensitive skin.[7,8] Meanwhile, SA is easy to precipitate out, and its recrystallisation could further induce skin irritation.[9] A recently introduced SA, named supramolecular salicylic acid (SSA), has been proved to improve solubility and further minimise the risk of irritation.[9]

In this study, we systemically evaluated the safety and efficacy of 30% SSA peeling on PPR patients. Transepidermal water loss (TEWL), skin hydration, erythema index and adverse events were investigated. This study might provide novel thought for the prevention and treatment of PPR.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Sixty PPR patients (21 males and 39 females) with age ranging from 21 to 44 years (mean age: 29.48 ± 6.94 years) were recruited from October 2018 to March 2019 in this study. The exclusion criteria of this research are as follows: patients with any photoelectric device treatment, filler injections or chemical peels within the past 6 months; patients with any topical or oral rosacea therapies during the previous 3 months; patients with photosensitive diseases; patients with other skin diseases such as seborrheic dermatitis and eczema; patients with serious systemic diseases; and pregnant or breastfeeding women. This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study design and treatment

Weinuona® Shumin™ facial cleanser and Weinuona® Shumin™ moisturiser were used twice daily in both groups. Metronidazole gel (Fangming Pharmacy Co., Ltd., Shandong, China) was applied on inflammatory lesions (papules/pustules) twice daily in both groups. Patients of the SSA group received three sessions of 30% SSA (BRODA®; Ruizhi Pharmacy Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) peeling at a 3-week interval. Each treatment was performed by a trained technician. After washing with the designated cleanser, patient's eyelids and lips were protected by cotton flakes. The formulation was then gently massaged onto their full face. During the process, water was applied to dilute the agent. Once frosting occurred, the face was rinsed thoroughly with lukewarm water. The total contact time ranged from 10 to 15 min. After the procedure, sun protection was suggested. All the patients were advised to avoid any other anti-rosacea treatment during the study.

Safety and efficacy assessment

All patients were evaluated at baseline and week 9. The values of TEWL, skin hydration and erythema index were measured using the probes of DermaLab (CORTEX®, Cortex Technology, Plastvaenget, Hadsund, Denmark). All measurements were performed after stabilisation of patients for at least 20 min in a controlled atmosphere room (22°C–25°C, 40%–60% humidity). All measurements were performed at three time points, and the mean values were calculated. Adverse reactions were recorded at each follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Data was analysed using SAS 9.4 statistical software. Continuous variables with normal distribution were analysed by t-tests. P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical information

Two patients were withdrawn from the study, as one developed contact dermatitis by metronidazole gel and the other one received other anti-rosacea therapy during the study period. In total, 58 patients completed this study including 30 patients in the SSA group and 28 patients in the control group. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline clinical details of the SSA group and the control group

| Characteristics | SSA group (n=30) | Control group (n=28) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 29.27±7.04 | 29.75±7.19* |

| Duration (years), mean±SD | 4.68±4.43 | 5.25±4.16* |

| Female, n (%) | 19 (63.33) | 19 (67.86) |

| Male, n (%) | 11 (36.67) | 9 (32.14) |

| TEWL, mean±SD | 18.86±2.20 | 19.39±2.11* |

| Skin hydration, mean±SD | 219.83±27.21 | 215.36±30.31* |

| Erythema index, mean±SD | 14.40±1.49 | 14.21±1.58* |

SD=standard deviation, SSA=supramolecular salicylic acid, TEWL=transdermal water loss. *P>0.05 for the control group versus SSA group

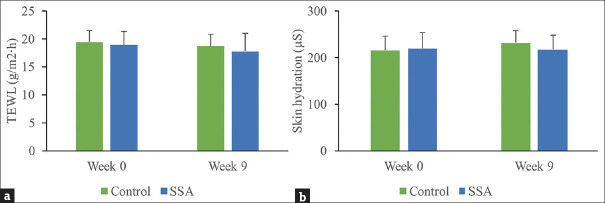

Safety evaluation of 30% SSA peeling by measuring TEWL and skin hydration

We measured TEWL and skin hydration of patients to investigate the safety of 30% SSA peeling. Decreased TEWL was found in the treatment group (17.74 ± 3.22 g/m2·h) and control group (18.63 ± 2.54 g/m2·h) after 9 weeks, but the differences were not statistically significant compared to baseline. No significant differences were found between the two groups at the end of treatment [Figure 1a]. At week 9, the hydration content was 230.73 ± 34.59 μS in the SSA group and 217.07 ± 30.41 μS in the control group. The hydration content increased slightly, but no statistical significance was observed compared to baseline in both the groups. No significant difference was found between the two groups at the end of the study as well [Figure 1b].

Figure 1.

Safety evaluation of SSA. (a) TEWL was measured in the control and SSA groups at week 0 and 9. (b) Skin hydration was measured in the control and SSA groups at week 0 and 9. SSA = supramolecular salicylic acid, TEWL = transdermal water loss

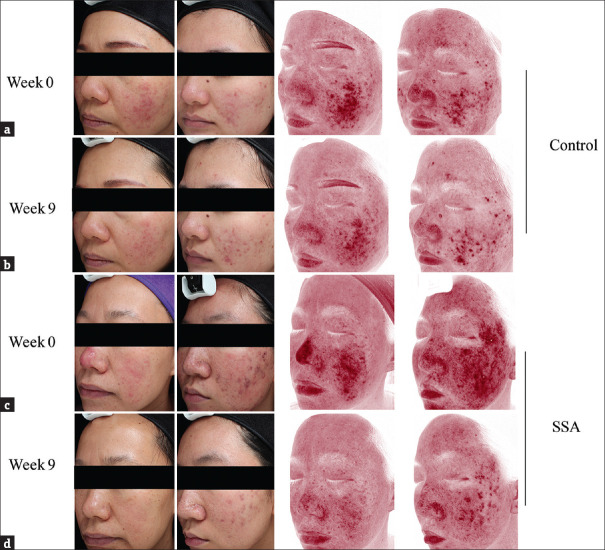

Efficacy evaluation of 30% SSA peeling by measuring erythema index and clinical observations

To measure the efficacy of 30% SSA peeling, erythema index was investigated. At week 9, the mean erythema index decreased significantly in both the groups compared to baseline (SSA group: 10.29 ± 1.34; control group: 12.5 ± 1.0) [Figure 2]. Meanwhile, the erythema index in the SSA group was significantly lower than that in the control group at week 9. In addition, significant apparent improvement of redness and papules/pustules was observed in the SSA group by Visia-CR® digital imaging system (Canfield Scientific, Parsippany, NJ, USA) [Figure 3].

Figure 2.

Efficacy evaluation of SSA. Erythema index was measured in the control and SSA groups at week 0 and 9. *P < 0.05 compared to the data of week 0; #P < 0.05 compared to the control group at week 9. SSA = supramolecular salicylic acid

Figure 3.

Digital photographs of PPR patients in the control and SSA groups. (a) Representative images of patients in the control group at week 0. (b) Representative images of patients in the control group at week 9. (c) Representative images of patients in the SSA group at week 0. (d) Representative images of patients in the SSA group at week 9. PPR = papulopustular rosacea, SSA = supramolecular salicylic acid

Adverse events

This study showed that all patients in the SSA group tolerated the procedures well despite reports of minor discomfort, such as burning and stinging, which were common reactions in chemical peels. Among them, 12 cases (40%) experienced facial erythema at the end of peeling, and the erythema faded away the next day. Slight exfoliation and crusting were reported in six cases (25%), and they were cleared in 4–6 days. All adverse reactions were minimal and transient. No pigmentation, hypopigmentation or other serious postoperative complications were reported in either group.

Discussion

Rosacea is a chronic and recurrent skin condition that affects the central face of middle-aged adults. The influence of the appearance and the physical discomfort caused by rosacea exert a negative impact on patients’ quality of life and psychological well-being.[10,11] PPR is clinically characterised by inflammatory papules/pustules and erythema in the central face, which could be accompanied by irritating symptoms such as burning, stinging or dryness.

The main traditional treatments for PPR include topical metronidazole, azelaic acid or ivermectin, and systemic therapies such as oral tetracyclines or isotretinoin.[12,13] Although most patients benefit from systemic treatments, there are still some patients who, for any reason, are unable or unwilling to receive systemic therapies. In this regard, tailoring individualised therapies to best suit the expectations of patients has become a new challenge for the clinicians. With the development of cosmetic dermatology, a wide range of therapeutic options are available, including laser, light-based therapies and chemical peels. Among them, chemical peeling is a popular choice since it is a convenient and affordable treatment without systemic side effects. It is reported that SA has been used for the treatment of acne vulgaris, pigmentary disorders, photodamage and other skin problems.[14,15] Data regarding the effectiveness and safety of SA treatment on PPR are limited.

Although the aetiology of PPR is not completely understood, it is clear that dysfunction of the neurovascular, innate and adaptive immune system could lead to a chronic pathological inflammatory state and further contribute to PPR. Presence of microorganisms, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumonia and Demodex folliculorum, seems to have an association with the inflammation related to PPR.[12] Anti-inflammatory therapy plays an important role in PPR treatment. SA is a β-hydroxyl acid with anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antifungal properties.[6] Its anti-inflammatory effect by acting on arachidonic acid cascade is much more prominent than that of other peeling agents. However, SA has a very low solubility in water due to its lipophilic characteristics and is normally administered as an alcoholic solution to completely dissolve it. This form has the tendency to cause some irritation reactions. Most of the patients with rosacea reported irritation sensations including burning, stinging and dryness due to the damage caused to the skin barrier in rosacea.[16,17] Due to its irritant potential, the safety of SA peeling in rosacea is a real concern. SSA has been believed to improve these side effects of SA. Firstly, SSA is a modified SA preparation using supramolecular engineering principles to surpass the SA solubility issues without changing its pharmacological behaviour. The new water-soluble complex is milder, with fewer side effects. Secondly, SSA is characterised by sustained release upon application. The SSA molecules are released when diluted with water, which can be controlled by a trained technician. In this manner, it may penetrate the skin slowly and is controllable at a low pH. These properties make it an ideal choice as a peeling agent in sensitive skin, and it might be a potential treatment strategy for PPR. Our results showed significant improvement of erythema index and clinical symptoms, which was apparent in the SSA group compared to the control group. No obvious adverse reactions were experienced by patients after treatment.

As a superficial peeling agent, 30% SSA causes injury of epidermis and then removes epidermal lipids due to its lipid-soluble nature. These effects might damage the skin barrier integrity. Both TEWL and skin hydration are considered as indicators of skin barrier integrity. In the present study, no statistically significant changes were observed in TEWL and skin hydration between the treatment group and the control group, indicating that the application of 30% SSA did not cause impairment of skin barrier.

In addition, we demonstrated that 30% SSA peeling could be helpful for the recovery of barrier function in rosacea, and the following potential mechanisms may account for this effect. Firstly, SSA has good anti-inflammatory effects, and the relief of inflammation in PPR could improve the functional repair of skin. Secondly, the regeneration of normal epidermal tissues after peels can also help accelerate the recovery of skin barrier function.

Limitations

In this study, objective measurements were used to objectively evaluate the efficacy and safety of SSA peeling on rosacea. However, there are also a few limitations to our study. One limitation was the short, 9-week duration; long-term follow-up is required to confirm the clinical effects and evaluate the relapse rates, as rosacea is a chronic relapsing condition. Another limitation was that patients did not evaluate their own rosacea symptoms such as flushing, burning and dryness with the treatment, since these symptoms could worsen if SSA caused impairment of skin barrier. Also, in this study, we did not evaluate the patients’ satisfaction with this treatment, which was valuable, especially for those who had experienced multiple types of therapy.

Conclusions

Our findings suggested that 30% SSA peeling can significantly improve the clinical symptoms of PPR patients. It is effective, safe and well tolerated without obvious side effects. Therefore, 30% SSA peeling may be considered as a new therapeutic option for the treatment of PPR.

Authors’ contributions

LX and BY conceived and designed the experiments; TX and HH performed the experiments; LX and BY wrote the paper.

Ethical statement

This study was assessed and approved by the medical ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University. All necessary consents were taken from the patients during this study. Trial registration number: ChiCTR2000029833.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Key Clinical Specialty Discipline Construction Programme of Fujian and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant Number 2019J01467).

References

- 1.Tan J, Almeida LM, Bewley A, Cribier B, Dlova NC, Gallo R, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: Recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:431–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Rosso JQ, Tanghetti EA, Baldwin HE, Rodriguez DA, Ferrusi IL. The burden of illness of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea and papulopustular rosacea: Findings from a web-based survey. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:17–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forton FMN, De Maertelaer V. Papulopustular rosacea and rosacea-like demodicosis: Two phenotypes of the same disease? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1011–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. The molecular pathology of rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin AN, Nakatsui T. Salicylic acid revisited. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:335–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arif T. Salicylic acid as a peeling agent: A comprehensive review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:455–61. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S84765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee HS, Kim IH. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1196–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2003.29384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelsohn JE. Update on chemical peels. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:55–72. doi: 10.1016/s0030-6665(03)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Yin S, Xia Y, Chen J, Ye C, Zeng Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of 2% supramolecular salicylic acid compared with 5% benzoyl peroxide/0.1% adapalene in the acne treatment: A randomized, split-face, open-label, single-center study. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2019;38:48–54. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2018.1518329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haber R, El Gemayel M. Comorbidities in rosacea: A systematic review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:786–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heisig M, Reich A. Psychosocial aspects of rosacea with a focus on anxiety and depression. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018;11:103–7. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S126850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivero AL, Whitfeld M. An update on the treatment of rosacea. Aust Prescr. 2018;41:20–4. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2018.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaller M, Almeida LM, Bewley A, Cribier B, Dlova NC, Kautz G, et al. Rosacea treatment update: Recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:465–71. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiest LG, Habig J. Chemical peel treatments in dermatology. Hautarzt. 2015;66:744–7. doi: 10.1007/s00105-015-3672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dayal S, Amrani A, Sahu P, Jain VK. Jessner's solution vs.30% salicylic acid peels: A comparative study of the efficacy and safety in mild-to-moderate acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:43–51. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addor FA. Skin barrier in rosacea. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:59–63. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20163541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng Z, Chen M, Xie H, Jian D, Xu S, Peng Q, et al. Claudin reduction may relate to an impaired skin barrier in rosacea. J Dermatol. 2019;46:314–21. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]