Abstract

Vacuolar/archaeal-type ATPase (V/A-ATPase) is a rotary ATPase that shares a common rotary catalytic mechanism with FoF1 ATP synthase. Structural images of V/A-ATPase obtained by single-particle cryo-electron microscopy during ATP hydrolysis identified several intermediates, revealing the rotary mechanism under steady-state conditions. However, further characterization is needed to understand the transition from the ground state to the steady state. Here, we identified the cryo-electron microscopy structures of V/A-ATPase corresponding to short-lived initial intermediates during the activation of the ground state structure by time-resolving snapshot analysis. These intermediate structures provide insights into how the ground-state structure changes to the active, steady state through the sequential binding of ATP to its three catalytic sites. All the intermediate structures of V/A-ATPase adopt the same asymmetric structure, whereas the three catalytic dimers adopt different conformations. This is significantly different from the initial activation process of FoF1, where the overall structure of the F1 domain changes during the transition from a pseudo-symmetric to a canonical asymmetric structure (PNAS NEXUS, pgac116, 2022). In conclusion, our findings provide dynamical information that will enhance the future prospects for studying the initial activation processes of the enzymes, which have unknown intermediate structures in their functional pathway.

Keywords: molecular motor, vacuolar ATPase, cryo-electron microscopy, single particle analysis, H+-ATPase, ATP synthase, ATPase, structure-function, enzyme mechanism

Abbreviations: cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; DDM, n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside; Tth, Thermus thermophilus; V/A-ATPase, vacuolar/archaeal-type ATPase; V-ATPase, vacuolar-type ATPase

Vacuolar/archaeal-type ATPase (V/A-ATPase) is an excellent rotary molecular machine that shares a common rotary catalytic mechanism with FoF1 ATP synthase (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). V/A-ATPases are found in archaea and some eubacteria and utilize a transmembrane electrochemical ion gradient to synthesize ATP in most cases (6, 7, 8, 9). V/A-ATPases are structurally and evolutionarily related to vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPase) (2, 9) but have evolved different regulatory mechanisms based on their function (5, 10, 11, 12, 13).

The thermophilic bacterium Thermus thermophilus (Tth) possesses V/A-ATPase, which functions as an ATP synthase in vivo (6, 7, 8, 14). V/A-ATPase has a simpler overall structure than the eukaryotic V-ATPase that has a subunit stoichiometry of A3B3D1E2F1G2d1a1c12 (Figs. 1A and S1) and has structural stability that allows for direct observation of the rotary motion in the enzyme by single-molecule experiments and X-ray crystallography of the subunits or subcomplexes (15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22).

Figure 1.

Cryo-EM maps of the V/A-ATPase and schematic representation of steady-state catalytic cycle driven by ATP hydrolysis.A, side view of the representative map of the whole complex. B, cross-sections of the nucleotide-binding sites (top) and A3B3 C-terminal region (bottom) of V2SO4 map viewed from the top. C, Three rotational states (state1–3) interconverted through a tri-site mechanism where the site occupancy alternates between two and three as shown in V2nuc and V3nuc, respectively. Schematic showing the three different catalytic states of AB subunits denoted ABopen, ABclosed, and ABsemi. As the rotor subunit (black arrow with bolt type) rotates 120°, three AB dimers altered to the next state; ABclosed to ABopen, ABopen to ABsemi, ABclosed to ABopen (e.g. state1 V3nuc→ state2 V2nuc). The activation process of nucleotide-depleted enzyme (ground state enzyme, upper) has not been elucidated. cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; V/A-ATPase, vacuolar/archaeal-type ATPase.

In the V/A-ATPase, the V1 domain (A3B3D1F1) can function as an ATP-driven rotary motor and ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, and ADP/Pi release that occur simultaneously at three catalytic sites of A3B3, respectively. This cooperative reaction produces conformational changes in the A3B3 stator, which induces a 120° rotation of the central DF rotor (6, 8, 13, 23). The catalytic cycle is often summarized as a circular reaction scheme that indicates catalytic events linked to the rotary position of the central axis (Fig. 1C). Single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) analysis of the V/A-ATPase identified three rotational states (state 1–3) and an asymmetric structure of the three AB dimers, termed “open (ABopen),” “semiclosed (ABsemi),” and “closed (ABclosed) (Fig. 1B). Even in the presence or absence of nucleotide binding, conformations of both ABsemi and ABclosed remained closed, which does not allow easy access of ATP to the catalytic sites (23, 24). Therefore, ATP binding occurs in ABopen where the catalytic site is fully open. In contrast, a recent structural study of bacterial FoF1 using cryo-EM revealed that nucleotide-depleted FoF1 comprises three catalytic β subunits, all of which adopt an open form (25). Thus, the accessibility of nucleotides to the three catalytic sites was significantly different between the F- and V/A-type ATPases in the absence of nucleotides.

Structural snapshots of V/A-ATPase under steady-state conditions were obtained using cryo-EM (23). These structures revealed that all three catalytic sites on the AB dimers were occupied by ATP/ADP under the waiting conditions for catalysis ([ATP] > Km) in the ATPase cycle (Fig. 1C, V3nuc structure). Contrary, only the catalytic site on ABopen was empty (Fig. 1C, V2nuc structure) under the waiting conditions for ATP binding ([ATP] < Km). These results support the tri-site mechanism of V/A-ATPase, where site occupancy alternates between two and three (26, 27, 28). Moreover, the structural snapshots indicate three catalytic processes simultaneously proceed (ⅰ) zipper movement in ABopen with the ATP, (ⅱ) ATP hydrolysis on ABsemi, and (iii) unzipper movement of ABclosed with the release of ADP and Pi. In other words, simultaneous interlocking of the three catalytic processes and 120° rotation of the axis are necessary for continuous catalytic reactions (23).

Although steady-state intermediate structures of VA-ATPase were unveiled in a previous study using cryo-EM, how the three catalytic sites of the enzyme are filled with nucleotides in the initial activation process remains unresolved. Because the A3B3 hexamer of the nucleotide-free V/A-ATPase (Vnucfree) also adopts an asymmetric conformation (ABopen, ABsemi, and ABclosed), the first ATP likely binds to the catalytic site on ABopen in Vnucfree. For ATP to bind to the following binding site, the conformation of ABclosed should be changed to ABopen with a 120° step of the rotor. However, it is unlikely that the 120° step of the rotor would occur only by the zippering motion of ABopen with ATP because simultaneous catalytic events at three catalytic sites are also required for the steady-state turnover of the V/A-ATPase. The measurement of ATPase activity of Tth V1-ATPases presents an initial lag with low ATPase activity and subsequent activation of the ATP hydrolysis reaction (29). In addition, the lag time was significantly shortened as the ATP concentration increased in the reaction solution. However, the conformational change process of V/A-ATPase from the initial state, referred to as the ground state, to the steady state upon ATP binding remains unknown (Fig. 1C).

In general, it is challenging to identify the initial catalytic state of the enzymes by canonical cryo-EM observation because the activation process is completed within a few seconds (30, 31, 32). Thus, structures focusing on the initial reactions of rotary ATPases have not yet been obtained.

Here, we report cryo-EM observations to capture the short-lived intermediates of the V1 domain under different reaction conditions and time points following initiation by ATP with sulfate, which extends the duration of the initial inactivated state of V/A-ATPase. The captured sequential intermediate structures provide the first insight into how V/A-ATPase changes its conformation from the initial state to the steady state through the sequential binding of ATP to its three catalytic sites.

Results

Extension of the initial activation process of V/A-ATPase upon sulfate addition

In this study, we used the V/A-ATPase, including TSSA mutation (A/S232A, T235S), which is much less susceptible to ADP inhibition than the wildtype enzyme (8, 14). The bound ADP was easily removed from V/A-ATPase by dialysis against phosphate buffer. We termed the V/A-ATPase without nucleotide Vnucfree (nucleotide-free V/A-ATPase) as the ground state structure. The resulting Vnucfree was reconstituted into a nanodisc and used for subsequent analysis.

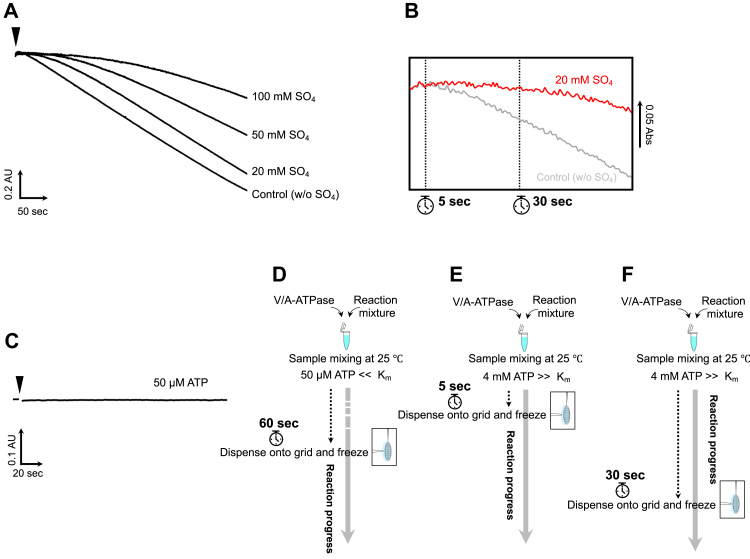

The initial lag phase of the ATP hydrolysis profile by Vnucfree was observed, suggesting the existence of initial inactivated intermediates (Fig. 2, A and B). This lag phase disappeared within a few seconds under saturating ATP conditions (Fig. 2A, control). The longer the activation time, the easier it is to capture short-lived intermediates using cryo-EM during the activation process for the initial inactivated V/A-ATPase. Therefore, sulfate ions, which are known to decrease the reaction rate as phosphate analogs, were added to the reaction mixtures to extend the initial lag phase (29). Expectedly, the initial lag time was significantly extended in the presence of sulfate under saturated ATP conditions, which is suitable for capturing snapshots of intermediates for a specified time interval (Fig. 2B). When comparing the sulfate concentration dependence on ATPase activity, it appears that the presence of 20 mM sulfate does not significantly affect the ATPase activity of the enzyme and only extends the duration of the initial lag (Figs. 2A and S2). In contrast, V/A-ATPase exhibited little ATPase activity at much lower ATP concentrations than the Km value (a final concentration of 50 μM) in the presence of 20 mM sulfate (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

Sulfate extends the duration of the initial intermediates of the V/A-ATPase.A, time-course of ATP hydrolysis catalyzed by the nucleotide-free V/A-ATPase (Vnucfree) under saturating ATP (a final concentration of 4 mM ATP) condition in the absence (control) or presence of sulfate at various concentrations as indicated. The ATPase activity of Vnucfree in the presence of 20 mM sulfate was 18 s−1, approximately equal to that of the control (17 s−1). ATPase activity of the enzyme in the presence of 50 mM or 100 mM sulfate was 14 or 12 s−1, respectively, where the ATPase activity was partially inhibited. The reaction was initiated by adding 20 pmol enzymes (shown by an arrowhead) to 2 ml of the assay mixture. B, magnified view of the initial lag phase in A. C, time-course of ATP hydrolysis catalyzed by Vnucfree under much lower ATP concentration than Km value (a final concentration of 50 μM ATP) in the presence of sulfate (a final concentration of 20 mM SO4). D–F, the experimental setup for EM grid preparation. D, 20 μM of ATP was added to the reaction mixture containing enzymes and incubated for 60 s at 25 °C before plunge freezing. E and F, 4 mM of ATP was added to the reaction mixture containing enzymes and incubated for 5 s (E) or 30 sed (F) at 25 °C before plunge freezing. V/A-ATPase, vacuolar/archaeal-type ATPase.

Structure of Vsemi1ATP following a 120° step by binding of ATP on the first catalytic site

Nanodiscs reconstituted with Vnucfree at a final concentration of 4 μM were mixed with ATP at final concentrations of 50 μM and 20 mM sulfate in the presence of an ATP regeneration system, and the mixture was then incubated at 25 °C for 60 s (Fig. 2D). The incubated reaction mixture was then applied to an EM grid and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane. The frozen enzymes were imaged by cryo-EM, followed by image processing using standard procedures (Fig. S3). The 1452 K particles were classified into three conformations, termed “state1” at 2.7 Å, “state2” at 3.1 Å, and “state3” at 3.2 Å, which were related by a rotation of DF subunit as shown in a previous study (23, 24, 33). To improve the local resolution of the V1 domain, the density of the membrane-embedded region of state1 was subtracted using the mask covering the V1 domain with the part of two stalk regions of the EG. Following refinement of the subtracted particles, we specified the mask range including the ABsemi and Aopen domains for a masked 3D classification procedure, thereby enabling the generation of cryo-EM maps of two different states at 2.8 and 3.2 Å resolution, respectively (Fig. S3).

The cryo-EM map at 2.8 Å resolution exhibited the asymmetrical structure of the A3B3 hexamer, as previously shown (23, 24), and had no nucleotide binding to ABopen. In contrast, spherical densities corresponding to sulfate ions were observed at the catalytic sites on both ABsemi and ABclosed (Fig. 3A). We termed this structure V2SO4. For another cryo-EM map at 3.2 Å resolution, the densities of a sulfate ion and ATP were observed in ABclosed and ABsemi, respectively (Fig. 3C). However, there was no density at the catalytic site of ABopen, where the first ATP likely binds as the first step of the reaction. The structure containing ATP at the ABsemi is termed Vsemi1ATP.

Figure 3.

Distinct nucleotide occupancy statuses between intermediates of each condition.A–E, cross-sections of each nucleotide-binding site of V2SO4 (A), V1ATP, (B), Vsemi1ATP (C), V2ATP (D), and V3ATP (E) viewed from the top are indicated in the top. ATP, ADP, and sulfate are colored blue, light blue, and magenta, respectively. Subunits are colored and labeled with text in the same color. Nucleotide-binding sites and density for nucleotides or sulfates bound at nucleotide-binding sites are shown at bottom. Each contour level for density shown as the blue mesh is indicated. Residues of B/R360, A/K234, A/S235, and A/V236 that interact with nucleotide or sulfate are shown as sticks. The map reveals relative density to nucleotides or sulfates on catalytic sites of each condition and no apparent extra density on the catalytic site of ABopen on V2SO4 and Vsemi1ATP.

It is unlikely that ATP binds directly to the catalytic site of ABsemi because of its closed structure. Therefore, ATP at the catalytic site of ABsemi is most likely derived from ATP bound to ABopen. This indicates that Vsemi1ATP is in the state after 120° rotation of the axis, following only one ATP binding to the catalytic site on ABopen of V2SO4. This expectation was supported by the results of the time-resolved experiment for V/A-ATPase under saturating ATP conditions, as described in the next chapter.

Structures of the V/A-ATPase incubated with saturating ATP for 5 s

The profile of ATPase activity of V/A-ATPase at 4 mM ATP indicates a lag time corresponding to the slow activation process of the initial inactivated intermediates (Fig. 2A). The activation process of V/A-ATPase was not completed within approximately 60 s, which is suitable for trapping intermediates at the indicated time. Therefore, V/A-ATPase was added to the reaction solution and incubated for 5 and 30 s, respectively (Fig. 2, E and F). Each sample was applied to an EM grid and imaged by cryo-EM, followed by single-particle analysis (Figs. S4 and S5). Particle images (86 K) of state1 were selected after 3D classification in the dataset resulting from the 5-s reaction mixture. Two classes were classified from the chosen particle images by masked 3D classification focused on the ABsemi and Aopen domains (Fig. S4). The structure referred to as V1ATP reconstituted from 54 K particles showed ATP binding to the catalytic site on ABopen and sulfate binding to the catalytic sites on both ABclosed and ABsemi (Fig. 3B). In structures reconstituted from 30 K particles, ATP molecules were identified in the catalytic sites on both ABopen and ABsemi, and sulfate was confirmed in the catalytic site on ABclosed (Fig. 3D). This structure was termed V2ATP. The V1ATP is an intermediate structure formed immediately after ATP binding to the ABopen of V2SO4. V2ATP is an intermediate structure formed immediately after ATP binding to Vsemi1ATP, since the catalytic site on ABopen of Vsemi1ATP is immediately occupied by ATP under saturating ATP conditions. These results suggest that ∼35% of the particles of V1ATP transition to Vsemi1ATP by a 120° rotation of the axis, followed by ATP binding to Vsemi1ATP, resulting in the generation of V2ATP.

Structures of V/A-ATPase incubated with saturated ATP for 30 s

After 3D masked classification with a mask containing ABsemi, two structures were obtained from the resulting dataset of the 30 s reaction mixture (Fig. S5). The structure reconstructed from 16 K particles was identical to the V1ATP obtained from the dataset of the 5 s reaction (Figs. S4 and S5). In another structure reconstructed from 19 K particles, ATP or ADP occupied all three catalytic sites. The structure of the V/A-ATPase containing three nucleotides referred as V3ATP was identical to V3nuc obtained under saturating ATP conditions in our previous study (23) (Figs. 3E and S5). By contrast, V2ATP disappeared under these conditions. These results indicate that all particles of V2ATP change their state to V3ATP/3nuc. For this transition, the 120° rotation of the rotor should occur in V2ATP, before ATP binding to empty ABopen, resulting in the generation of V2nuc structure (empty ABopen, ABsemi with ATP, and ABclosed with ADP and Pi). However, neither V2ATP nor other intermediates were identified under these conditions. In contrast, V1ATP was still identified in the dataset from the reaction mixture 30 s after reaction initiation, suggesting that the transition from V1ATP to Vsemi1ATP did not occur immediately. Together, these results suggest that 120° rotation does not occur immediately by the zippering motion of ABopen with ATP in the absence of ATP binding on ABsemi. This is consistent with the results of a previous study, in which both the zippering motion of ABopen with ATP and hydrolysis of ATP in ABsemi drive the unzipper motion of ABclosed with the release of ADP and Pi, which are coupled simultaneously with the 120° rotation of the shaft (23).

Different conformations of ABsemi with different ligands

After the refinement with signal subtraction for the membrane domain, different conformations of ABsemi were identified from the masked 3D classification procedure (Figs. S3–S5). Cα root means square displacement values between semiclosed B subunits indicated a significant structural difference in the C-terminal helix bundle between V1ATP and Vsemi1ATP when superimposed on the N-terminal β-barrel domain (Table S1). The C-terminal helix bundle of the B subunit changed to a more open conformation upon ATP binding (Fig. S6A, black square area). In contrast, there was no significant difference between the semiclosed A subunits (Fig. S6, top). Considering the difference in ligands between these states, ATP binding induces conformational changes in the C-terminal helix bundle of the semiclosed B subunit.

Furthermore, the contour levels on the maps for ATP binding to ABsemi varied between the states (Fig. 3). Two maps of V2ATP and V3ATP showed an apparent density for ATP binding to each catalytic site on ABsemi when contoured at 7σ (standard deviation). In contrast, the density for ATP binding to ABsemi in Vsemi1ATP had to be lowered to 1.5σ for visualization (Fig. 3, C, D, and E). The atomic displacement (B) factor of ATP binding to ABsemi in the V2ATP and V3ATP was in the range of 30 to 59 and 41 to 77 Å2, respectively, although Vsemi1ATP showed a higher B factor range of 112 to 133 Å2. The low contour threshold of ATP binding to the ABsemi of Vsemi1ATP is associated with a high B factor, which implies greater flexibility and/or heterogeneity within the nucleotide. These results imply multiple ligand conformations of the nucleotide binding to the catalytic site on ABsemi of Vsemi1ATP in the initial reaction process.

Discussion

Cryo-EM snapshot analysis of V/A-ATPase indicated that the 120° step of the axis is driven by three reactions occurring simultaneously at the three catalytic sites (23). This raises questions on how nucleotide-free V/A-ATPase transitions to a steady state by ATP binding to the catalytic sites on the enzyme. Previous studies have suggested the existence of an initial inactivated state of V1-ATPase (29). In this study, we attempted to capture short-lived initial intermediates of V/A-ATPase in the presence of sulfate, which can temporally stabilize the initial intermediate.

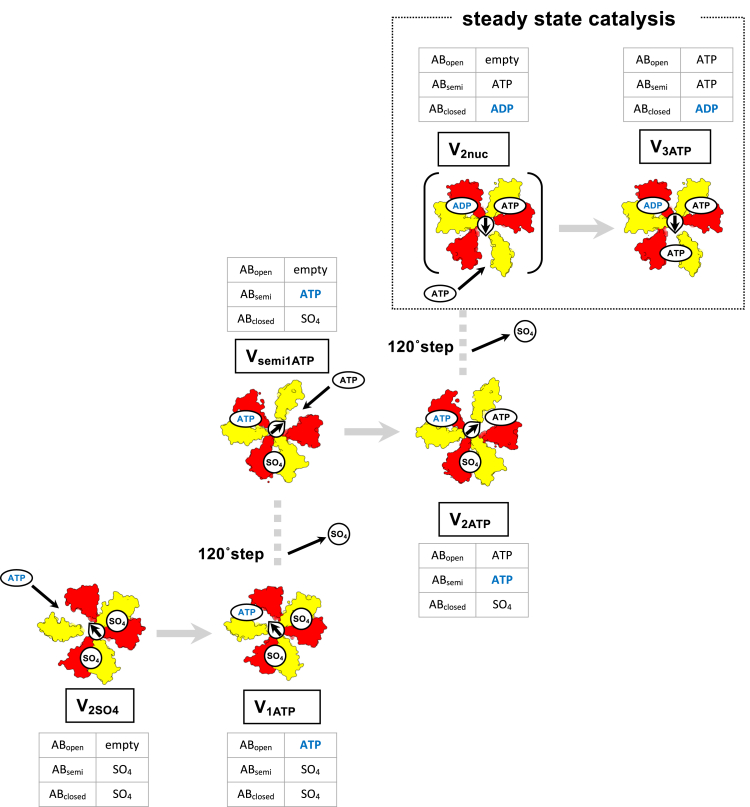

The transition process from the initial state to the steady state is summarized in Fig. 4. Under the waiting conditions for ATP binding ([ATP] < Km), ABopen in the V/A-ATPase adopts an empty form since ATP binding to the catalytic site on ABopen is a rate-limiting step, and other catalytic reaction(s) are mostly completed while waiting for ATP binding. Consequently, Vsemi1ATP was obtained under waiting conditions for ATP binding. In other words, Vsemi1ATP is the state following 120° rotation of the rotor in V1ATP (Fig. 4, lower to middle). This indicates that one ATP binding to ABopen can initiate a 120° step of the axis when an inhibitory ADP does not occupy ABclosed.

Figure 4.

The activation process of the ground state of the V/A-ATPase. Cryo-EM maps for each state are shown as surfaces, colored as in Figure 1. DF axis is shown as an arrow to clarify the scheme, and corresponding tables for all AB pairs observed in the structures are indicated. In the initial phase, V2SO4 is activated by binding ATP colored blue to the ABopen, then changes its conformation to V1ATP (lower left). ATP binding to the ABopen in V1ATP induces the release of sulfate binding to the ABclosed with the axis rotation in 120° step (to the middle from lower left). Consequently, V1ATP changes its conformation to Vsemi1ATP. Vsemi1ATP changes its conformation to V2ATP in succession following ATP binding to the ABopen (middle). ATP binding to Vsemi1ATP is expected to induce the release of remaining sulfate binding to the ABclosed with the axis rotation in 120° step (to the right upper from the middle), and finally, V2ATP changes its conformation to V3ATPvia V2nuc and enters the continuous catalytic cycle. cryo-EM, cryo-electron microscopy; V/A-ATPase, vacuolar/archaeal-type ATPase.

Both V1ATP and V2ATP were identified in the resulting dataset from the reaction solution after 5 s under the ATP-saturating condition ([ATP] > Km). The catalytic sites on ABopen in both V1ATP and V2ATP are filled with ATP because ATP binding to ABopen is not a rate-limiting step. Consequently, V1ATP is apparently in the state immediately after ATP binds to V2SO4 (Fig. 4, lower). Similarly, V2ATP is in the state immediately after ATP binding to the catalytic site on ABopen in Vsemi1ATP (Fig. 4, middle). V2ATP disappeared in the resulting dataset from the reaction solution after 30 s, while V1ATP was still identified (Fig. S5), indicating that V2ATP is a short-lived intermediate compared to V1ATP. This observation implies that ATPase activity lagged because of a delayed transition from V1ATP to V2ATP via Vsemi1ATP in the initial reaction. Instead, V3ATP would be identified in the same dataset. The V3ATP is likely derived from V2nuc, where ABopen is empty (Fig. 4, upper box (23)). Once all V2ATP change to V2nuc, the steady-state catalysis continues by the tri-site mechanism (Fig. 4, upper box).

In the presence of 20 mM sulfate, the obtained intermediate structures have occluded sulfate in the ABclosed. The binding of sulfate to the catalytic site on ABclosed is likely to stabilize its closed conformation, hampering the 120° step of the axis by the zippering motion of ABopen with ATP. Nevertheless, our results indicated that V2SO4 and Vsemi1ATP finally transformed to V3ATP (ATP/ADP occupies all three AB) by sequential binding of ATP to the catalytic sites (Fig. 4). This suggests that sulfate binding to the catalytic site on ABclosed weakly stabilizes the closed structure of the catalytic site. In contrast, the ADP-inhibited state of the wildtype V/A-ATPase is defective in hydrolyzing ATP, where the unzippering motion of ABclosed is hampered by ADP binding to the catalytic site on ABclosed (23, 24).

Assuming that the structural transition from V1ATP to Vsemi1ATP is a rate-limiting step in the activation process, V1ATP is likely to be identified even at 50 μM ATP. However, approximately 95% of the particles were classified as V2SO4, and V1ATP was not identified under 50 μM ATP. The particles of the V1 domain are classified into different intermediates according to the difference in the ABsemi structure due to the bound ligand (Figs. S3–S5). Therefore, it is possible that the V1ATP particles were not distinguished from the V2SO4 particles, and the V1ATP structure was not identified.

Our structural snapshots revealed that the three AB conformations, referred to as “open,” “closed,” and “semiclosed” form, for each three catalytic AB pair of the V/A-ATPase was maintained during the activation process of the ground state enzyme, regardless of nucleotide binding status. A recent structural study of bacterial FoF1 using cryo-EM single particle analysis revealed open conformations of all three catalytic β subunits in the nucleotide-depleted enzyme (25). This structure significantly differs from the canonical F1 structure, which contains two closed β subunits and one open β subunit. Furthermore, the first ATP under uni-site conditions was hydrolyzed at βTP, followed by a structural transition of open βTP to closed βDP. The FoF1 after uni-site catalysis adopts a structure with two open β and one closed β subunit. The structural plasticity of the F1 domain is in contrast to the structural rigidity of the V1 domain, which maintains the same asymmetric structure independent of nucleotide occupancy at the catalytic sites.

In summary, we identified intermediate structures that appear during the transition from the initial state to the steady state, which cannot be obtained by canonical structural analysis using cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography. Due to the limitation of current experimental techniques, a detailed knowledge of conformational changes in molecular motor is missing. In addition to the analysis of the steady-state function of the V/A-ATPase, elucidating the activation process of the enzyme will pave the way for a complete understanding of the molecular mechanism of the rotational molecular motor.

Experimental procedures

Preparation of V/A-ATPase for biochemical assays and cryo-EM imaging

The V/A-ATPase containing His3 tags on the C terminus of each c subunit and the TSSA mutation (S232A and T235S) on the A subunit were isolated from T. thermophilus membranes as previously described (14), with certain modifications. The enzyme solubilized from the membranes with 10% Triton X-100 was purified by Ni2+-NTA affinity with 0.03% dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM). For bound nucleotide removal, the eluted fractions containing V/A-ATPase were dialyzed against 200 mM sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, and 0.03% DDM overnight at 25 °C with three buffer changes, followed by dialysis against 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.03% DDM (TE buffer) before anion exchange chromatography using a 6 ml Resource Q column (GE Healthcare). Nucleotide-free Tth V/A-ATPase (Vnucfree) was eluted with a linear NaCl gradient using TE buffer (0–500 mM NaCl, 0.03% DDM). The eluted fractions containing Vnucfree were concentrated to ∼10 mg/ml using Amicon 100k molecular weight cut-off filters (Millipore). For nanodisc incorporation, 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero3-phosphorylcholine (Avanti) was used to form lipid bilayers in reconstruction, as previously described (23, 33). Purified Vnucfree solubilized in 0.03% n-DDM was mixed with the lipid stock and membrane scaffold protein MSP1E3D1 (Sigma) at a specific molar ratio of enzyme: MSP1E3D1:1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-glycero3-phosphorylcholine lipid = 1:4:520 and incubated on ice for 0.5 h. Then, 200 μl of Bio Beads SM-2 (Bio-Rad) equilibrated with a wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl) was added to the 500 μl mixture. After 2 h of incubation at 4 °C with gentle stirring, an additional 300 μl of Bio Beads was added, and the mixture was incubated overnight at 4 °C to form the nanodiscs. The supernatant of the mixture containing Vnucfree reconstituted into nanodiscs was loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column equilibrated with the wash buffer. The peak fractions were collected, analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and concentrated to 4 mg/ml. The prepared V/A-ATPase was immediately used for biochemical assays or cryo-grid preparation, as Vnucfree aggregates within a few days.

Biochemical assay

ATPase activity was measured at 25 °C using an enzyme-coupled ATP-regenerating system as described previously (14, 23). The reaction mixture contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM KCl, different concentrations of ATP-Mg, 2.5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), 50 μg/ml pyruvate kinase (PK), 50 μg/ml lactate dehydrogenase, and 0.2 mM NADH in a final volume of 2 ml. The reaction was initiated by adding 20 pmol of enzymes to 2 ml of the assay mixture with or without sulfate, and the rate of ATP hydrolysis was monitored, as the rate of oxidation of NADH was determined by the absorbance decrease at 340 nm.

Cryo-EM imaging

Sample vitrification was performed using a semi-automated device (Vitrobot, FEI). The reaction basal buffer (RB buffer) containing 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 100 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM PEP, 100 μg/ml PK, and 20 mM ammonium sulfate was used under different reaction conditions. For Vnucfree with a low concentration of ATP, 4 μM of the enzyme was mixed with the same volume of × 2 RB buffer containing 100 μM ATP-Mg. Then, the mixtures were incubated for 60 s at 25 °C; then 2.4 μl of sample mixture was transferred to a glow-discharged grid (Quantifoil R1.2/1.3, 300 Mesh, molybdenum) (Fig. 2D). The grid was then automatically blotted once from both sides with filter paper for a 6 s blot time. The grid was then plunged into liquid ethane with no delay. For Vnucfree with saturated ATP, 4 μM of the enzyme was mixed with the same volume of × 2 RB buffer containing 8 mM ATP-Mg. The mixtures were incubated for 5 or 30 s at 25 °C to resolve intermediates during the initial phase, followed by blotting and vitrification (Fig. 2, E and F).

For Vnucfree, under the waiting conditions for ATP binding ([ATP] < Km), cryo-EM movie collection was performed with a CRYOARM 300 (JEOL) operating at an accelerating voltage of 300 keV and equipped with a K3 (Gatan) direct electron detector in electron counting mode (CDS, (34)), using the data collection software SerialEM (35). The pixel size was 0.81 Å/pix ( × 60,000), and a total dose of 50.0 e− Å−2 (1.0 e− Å−2 per frame) with a total 1.5 s exposure time (50 frames) with a defocus range of −1.2 to −2.4 μm. The image processing steps for the reaction conditions are summarized in Fig. S3.

For time-resolved data in Vnucfree under saturating ATP conditions, cryo-EM imaging was performed using a Titan Krios (FEI/Thermo Fisher) operating at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV and equipped with a direct K3 (Gatan) electron detector in electron counting mode (CDS, (34)). Data collection was carried out using SerialEM software (35) at a calibrated magnification of 0.83 Å pixel−1 ( × ,105,000) and a total dose of 50.0 e− Å−2 (or 1.0 e− Å−2 per frame) (where e− specifies electrons) with a total 5 s exposure time. The defocus range was −0.8 to −1.8 μm. Data were collected from 48 video frames. Image processing steps for 5 and 30 s time points are summarized in Figs. S4 and S5, respectively.

Image processing

Image processing steps for each reaction condition are summarized in Figs. S3–S5. Collected data were processed with RELION (36), and Cryosparc (37), motion-corrected with the MotionCor2 algorithm (38); initial contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters from each dose-weighted image were determined by using CTFFIND4 (39). The details were identical to those described in our previous paper (23). For three datasets, several rounds of two-dimensional classification with 5x binned particles using C1 symmetry were performed to select intact V/A-ATPase particles. Then they were applied to 3D classification to separate three states (state1-3), which were related by a rotation of the DF subunit. Each selected particle was re-extracted at full pixel size and applied to 3D autorefinements, followed by CTF refinement and Bayesian polishing. The final maps of the holo-complex were generated using another round of CTF refinement and 3D autorefinements using soft masks. The membrane domain was visible but less clear than the hydrophilic V1 domain in a holo-enzyme map. This seemed to be due to the structural flexibility resulting from the movement of the membrane domain relative to V1 (23, 24, 33). To improve the local resolution of the V1 domain, the density of the membrane-embedded region of state 1 was subtracted by using the mask covering the V1 and C-terminal domain of EG subunits (V1EG). The refinements provided the density maps for V1EG under each condition at 2.4 to 3.0 Å resolution (Figs. S3–S5).

For V1EG under the condition of a low ATP concentration dataset, refined particles (216,617 particles in total) were applied to additional rounds of 3D no-alignment classification (regularization parameter T = 20, the number of classes k = 6) with a mask containing the semiclosed AB and the open A subunit to identify substrates after conventional 3D classification. Among these classes, 145,880 particles belonging to V2SO4, and 39,101 particles belonging to Vsemi1ATP were selected for further refinement.

Similar procedures were used to process V1EG with a saturating ATP dataset. For the time-resolved dataset in V1EG at 5-s time point with saturating ATP, refined particles (86,828 particles in total) were applied to additional rounds of 3D no-alignment classification (regularization parameter T = 20, the number of classes k = 5) with a mask containing the ABsemi and the open A subunit to identify substrates after conventional 3D classification. Among these classes, 54,047 particles belonging to V1ATP and 30,284 particles belonging to V2ATP were selected for further refinement.

For the time-resolved dataset in V1EG at the 30 s time point with saturating ATP, refined particles (46,901 particles in total) were applied to additional rounds of 3D no-alignment classification (regularization parameter T = 32, the number of classes k = 4) with a mask containing the ABsemi and the open A subunit to identify substates after conventional 3D classification. Among these classes, 19,234 particles of V3ATP and 15,867 particles of V1ATP were selected for further refinement.

The soft masks of V1EG for different substrates were further applied to the continued 3D autorefinements, resulting in the overall resolution reported in Table S2 after postprocessing, including soft masking and B-factor sharpening. Alternative postsharpening was performed using DeepEMhancer (40). The resolution was based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation criterion (0.142). The local resolution was calculated using ResMap (Fig. S7A, (41)). Two maps of V1ATP identified from different datasets were nearly identical; hence, a higher resolution map of V1ATP from the 5 s time point dataset was used for further analysis.

Model building, refinement, and validation

Maps from DeepEMhancer were used for model building, refinement, and subsequent structural interpretation. The V1EG model of the V/A-ATPase was adopted from the 3.1 Å V1EG structure (PDB accession no. 7VAL) as the initial model (23). With 2.5 to 3.1 Å V1EG density maps, we could model side chains and local geometry to achieve higher accuracy (Fig. S7A). The initial model was docked into the cryo-EM map using UCSF ChimeraX (42), and sulfate ions were built into COOT (43), followed by several rounds of real-space refinement using Phenix (44, 45). The initial model manually corrected residue by residue in COOT (43) regarding side-chain conformations. The iterative process using COOT (43) and ISOLDE (46) was performed for several rounds to correct the remaining errors until the model agreed well with the geometry (Table S2). Cross-validation was carried out by comprehensive validation in Phenix (44, 45), and the map to model Fourier shell correlation curves was calculated (Fig. S7B). Root means square displacement values between the atomic models and structural figures were calculated using the UCSF chimeraX (42).

Data availability

Cryo-EM density maps and corresponding atomic models have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and Protein Data Bank (PDB), respectively, with the following accession numbers (EMDB, PDB): V1ATP (EMD-34362, 8GXU), V2ATP (EMD-34363, 8GXW), V3ATP (EMD-34364, 8GXX), V2SO4 (EMD-34365, 8GXY), Vsemi1ATP (EMD-34366, 8GXZ). The data that support the findings of this studies are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the members of the Yokoyama Lab and Mitsuoka Lab for their continuous support and technical assistance. We also thank Dr T Nishizawa and Dr F Makino affiliated with University of Tokyo (present affiliation; Yokohama City University) and JEOL Ltd, respectively, for helping with the electron microscopy data collection.

Author contributions

K. Y. conceptualization; A. N., K. Y., and J. K. methodology; A. N., K. Y., and J. K. investigation; A. N., K. M., K. Y. and J. K. formal analysis; A. N. and K. Y. writing–original draft; K. Y. and K. M. writing–review & editing; A. N., K. Y., K. M., and J. K. funding acquisition; K. Y. resources; K. Y. and A. N. supervision.

Funding and additional information

We acknowledge support from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI; Grant No. 20H03231 to K. Y., 20K06514 to J. K.), Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellow (Grant No. 20J00162 to A. N.), Naito Foundation to J. K. (Grant No. 115), and Takeda Science Foundation to J. K. and K. Y. This work was supported by Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from AMED under Grant Number JP17 AM0101001 (support number 1312) and the Nanotechnology Platform of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) (Project Number. JPMXP09A21OS0008).

Edited by Joseph Jez

Supporting information

References

- 1.Kuhlbrandt W. Structure and mechanisms of F-type ATP synthases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019;88:515–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-110903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forgac M. Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:917–929. doi: 10.1038/nrm2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida M., Muneyuki E., Hisabori T. ATP synthase—a marvellous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:669–677. doi: 10.1038/35089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer P.D. The ATP synthase--a splendid molecular machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:717–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kühlbrandt W., Davies K.M. Rotary ATPases: a new twist to an ancient machine. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 2016;41:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokoyama K., Imamura H. Rotation, structure, and classification of prokaryotic V-ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2005;37:405–410. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokoyama K., Oshima T., Yoshida M. Thermus thermophilus membrane-associated ATPase. Indication of a eubacterial V-type ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:21946–21950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imamura H., Nakano M., Noji H., Muneyuki E., Ohkuma S., Yoshida M., et al. Evidence for rotation of V1-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:2312–2315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0436796100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muench S.P., Trinick J., Harrison M.A. Structural divergence of the rotary ATPases. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2011;44:311–356. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane P.M. Disassembly and reassembly of the yeast vacuolar H(+)-ATPase in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17025–17032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kishikawa J., Nakanishi A., Furuike S., Tamakoshi M., Yokoyama K. Molecular basis of ADP inhibition of vacuolar (V)-type ATPase/synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:403–412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart A.G., Sobti M., Harvey R.P., Stock D. Rotary ATPases: models, machine elements and technical specifications. Bioarchitecture. 2013;3:2–12. doi: 10.4161/bioa.23301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazhab-Jafari M.T., Rubinstein J.L. Cryo-EM studies of the structure and dynamics of vacuolar-type ATPases. Sci. Adv. 2016;2 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano M., Imamura H., Toei M., Tamakoshi M., Yoshida M., Yokoyama K. ATP hydrolysis and synthesis of a rotary motor V-ATPase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20789–20796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801276200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furuike S., Nakano M., Adachi K., Noji H., Kinoshita K., Jr., Yokoyama K. Resolving stepping rotation in Thermus thermophilus H+ -ATPase/synthase with an essentially dragfree probe. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:233. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwata M., Imamura H., Stambouli E., Ikeda C., Tamakoshi M., Nagata K., et al. Crystal structure of a central stalk subunit C and reversible association/dissociation of vacuole-type ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:59–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305165101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makyio H., Iino R., Ikeda C., Imamura H., Tamakoshi M., Iwata M., et al. Structure of a central stalk subunit F of prokaryotic V-type ATPase/synthase from Thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2005;24:3974–3983. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee L.K., Stewart A.G., Donohoe M., Bernal R.A., Stock D. The structure of the peripheral stalk of Thermus thermophilus H+ -ATPase/synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:373–378. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murata T., Yamato I., Kakinuma Y., Leslie A.G., Walker J.E. Structure of the rotor of the V-type Na+ -ATPase from Enterococcus hirae. Science. 2005;308:654–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1110064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasan S., Vyas N.K., Baker M.L., Quiocho F.A. Crystal structure of the cytoplasmic N-terminal domain of subunit I, a homolog of subunit a, of V-ATPase. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;412:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maher M.J., Akimoto S., Iwata M., Nagata K., Hori Y., Yoshida M., et al. Crystal structure of A3B3 complex of V-ATPase from Thermus Thermophilus. EMBO J. 2009;28:3771–3779. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagamatsu Y., Takeda K., Kuranaga T., Numoto N., Miki K. Origin of asymmetry at the intersubunit interfaces of V1-ATPase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Mol. Biol. 2013;425:2699–2708. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kishikawa J., Nakanishi A., Nakano A., Saeki S., Furuta A., Kato T., et al. Structural snapshots of V/A-ATPase reveal the rotary catalytic mechanism of rotary ATPases. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1213. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakanishi A., Kishikawa J.I., Tamakoshi M., Mitsuoka K., Yokoyama K. Cryo EM structure of intact rotary H(+)-ATPase/synthase from Thermus thermophilus. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:89. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02553-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano A., Kishikawa J.I., Nakanishi A., Mitsuoka K., Yokoyama K. Structural basis of unisite catalysis of bacterial FoF1-ATPase. PNAS Nexus. 2022 doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyer P.D. Catalytic site forms and controls in ATP synthase catalysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1458:252–262. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Löbau S., Weber J., Senior A.E. Nucleotide occupancy of F1-ATPase catalytic sites under crystallization conditions. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:15–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe R., Noji H. Timing of inorganic phosphate release modulates the catalytic activity of ATP-driven rotary motor protein. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3486. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokoyama K., Muneyuki E., Amano T., Mizutani S., Yoshida M., Ishida M., et al. V-ATPase of Thermus thermophilus is inactivated during ATP hydrolysis but can synthesize ATP. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20504–20510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank J. Time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy: recent progress. J. Struct. Biol. 2017;200:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoder N., Jalali-Yazdi F., Noreng S., Houser A., Baconguis I., Gouaux E. Light-coupled cryo-plunger for time-resolved cryo-EM 212(3):107624. J. Struct. Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dandey V.P., Budell W.C., Wei H., Bobe D., Maruthi K., Kopylov M., et al. Time-resolved cryo-EM using Spotiton. Nat. Met. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0925-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishikawa J.I., Nakanishi A., Furuta A., Kato T., Namba K., Tamakoshi M., et al. Mechanical inhibition of isolated V(o) from V/A-ATPase for proton conductance. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.56862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun M., Azumaya C.M., Tse E., Bulkley D.P., Harrington M.B., Gilbert G., et al. Practical considerations for using K3 cameras in CDS mode for high-resolution and high-throughput single particle cryo-EM. J. Struct. Biol. 2021;213 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2021.107745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mastronarde D.N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheres S.H. Relion: implementation of a bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Punjani A., Rubinstein J.L., Fleet D.J., Brubaker M.A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Met. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng S.Q., Palovcak E., Armache J.-P., Verba K.A., Cheng Y., Agard D.A. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Met. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohou A., Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez-Garcia R., Gomez-Blanco J., Cuervo A., Carazo J.M., Sorzano C.O.S., Vargas J. A deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Commun. Biol. 2020;4:874. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02399-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kucukelbir A., Sigworthe F.J., Tagare H.D. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat. Met. 2014;11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Meng E.C., Couch G.S., Croll T.I., et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W.G., Cowtan K. Features and development of coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Afonine P.V., Poon B.K., Read R.J., Sobolev O.V., Terwilliger T.C., Urzhumtsev A., et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 2018;74:531–544. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebschner D., Afonine P.V., Baker M.L., Bunkóczi G., Chen V.B., Croll T.I., et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2019;75:861–877. doi: 10.1107/S2059798319011471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Croll T.I. Isolde: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 2018;74:519–530. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318002425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Cryo-EM density maps and corresponding atomic models have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and Protein Data Bank (PDB), respectively, with the following accession numbers (EMDB, PDB): V1ATP (EMD-34362, 8GXU), V2ATP (EMD-34363, 8GXW), V3ATP (EMD-34364, 8GXX), V2SO4 (EMD-34365, 8GXY), Vsemi1ATP (EMD-34366, 8GXZ). The data that support the findings of this studies are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.