Abstract

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS) is a sulfur compound of importance for the organoleptic properties of beer, especially some lager beers. Synthesis of DMS during beer production occurs partly during wort production and partly during fermentation. Methionine sulfoxide reductases are the enzymes responsible for reduction of oxidized cellular methionines. These enzymes have been suggested to be able to reduce dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as well, with DMS as the product. A gene for an enzymatic activity leading to methionine sulfoxide reduction in Saccharomyces yeast was recently identified. We confirmed that the Saccharomyces cerevisiae open reading frame YER042w appears to encode a methionine sulfoxide reductase, and propose the name MXR1 for the gene. We found that Mxr1p catalyzes reduction of DMSO to DMS and that an mxr1 disruption mutant cannot reduce DMSO to DMS. Mutant strains appear to have unchanged fitness under several laboratory conditions, and in this paper I hypothesize that disruption of MXR1 in brewing yeasts would neutralize the contribution of the yeast to the DMS content in beer.

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS) is a thioether of importance for the aroma and flavor of beer. DMS levels in lager beers regularly exceed the taste threshold level of approximately 30 μg/liter (17). Above the taste threshold level but below approximately 100 μg/liter, DMS contributes to the distinctive taste of some lager beers. When present at more than 100 μg/liter, DMS may impart a usually undesirable flavor described as “cooked sweet corn.” DMS found in beer may be derived through thermal degradation of S-methyl methionine during kiln drying of the malt and wort preparation, and it has been suggested that this is the only pathway of significance for the final DMS content in beer (10, 11). However, there is evidence suggesting that enzymatic conversion of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to DMS by the brewing yeast is important and, under some circumstances, may be the major source of DMS in beer (16). See reference 2 for a review of DMS formation during beer production.

Saccharomyces yeasts contain an NADPH-dependent enzymatic activity that reduces DMSO to DMS (1, 3, 29). A methionine sulfoxide (MetSO) reductase has been isolated from yeast (7, 21) and may be responsible for the DMSO reductase activity (1, 3–6). This enzyme has a higher affinity for MetSO than for DMSO (5, 6), and MetSO inhibits DMSO reduction (1, 3, 6). Thus, the degree of MetSO formation during the preparation of wort influences the degree of DMSO reduction.

The nitrogen content of the growth medium also affects DMS formation. High levels of easily assimilated nitrogen keep DMSO reductase activity at a low level, whereas enzyme activity increases under nitrogen-limiting conditions (13). The high nitrogen content of most worts should keep DMSO reduction at the basal level during fermentation.

Recently, the YER042w open reading frame (ORF) was disrupted in a strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (19). The disruptant was unable to reduce peptide-bound MetSO and retained only 33% of the parental reduction activity against free MetSO; the YER042w-encoded enzyme was shown to be a MetSO reductase (19). We propose the name MXR1 for this gene. Our objective in this study was to test the hypothesis that MXR1 encodes an enzyme responsible for both MetSO reduction and reduction of DMSO to DMS during fermentation of brewer’s wort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains of bacteria and yeast and microbiological methods.

The yeast strains used in this study were S. cerevisiae S288C (MATα SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1), M1997 (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1), and M3750 (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 ura3) (a ura3 derivative of M1997); Saccharomyces carlsbergensis M204 (Carlsberg production strain) (syn. of Saccharomyces pastorianus); and Saccharomyces monacensis CBS1503 (syn. of Saccharomyces pastorianus). Escherichia coli DH5α (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom) was used for selection and propagation of plasmid DNA. SC (synthetic complete) and SD (synthetic dextrose) media were prepared as described by Sherman (25). MP medium was identical to SD medium, except that yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate was used and 2 g of proline per liter was included to serve as the nitrogen source. YPD medium contained 1% Bacto Yeast Extract (Difco, Detroit, Mich.), 2% Bacto Peptone (Difco), and 2% glucose. Sulfur-free B medium was prepared by the method of Cherest and Surdin-Kerjan (9). Brewer’s wort had a gravity of 14.5% Plato and was autoclaved before use. Yeast was grown at 30°C. S. cerevisiae was transformed essentially by the method of Schiestl and Gietz (24).

DNA manipulation.

Plasmid DNA was prepared from E. coli by the method of Sambrook et al. (23) or by using Maxiprep columns (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). DNA manipulations were performed as described by the manufacturers of the enzymes (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Hvidovre, Denmark; Promega, Madison, Wis.; or New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). PCR was performed with Perkin-Elmer Amplitaq polymerase (Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Branchburg, N.J.) as specified by the manufacturer.

Disruption of the YER042w ORF.

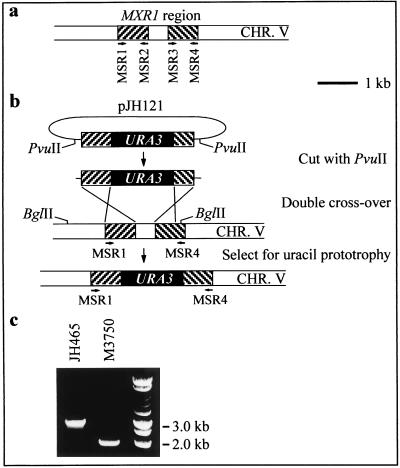

The one-step integration approach of Rothstein (22) was used to exchange most of the MXR1 (YER042w) coding region with a functional URA3 gene (Fig. 1), thereby converting the parental strain, M3750, to uracil prototrophy. A 727-bp DNA fragment, covering nucleotide positions −703 to +24 relative to the start codon of MXR1, was generated by PCR with oligonucleotide primers MSR1 and MSR2 (Fig. 1a) and S. cerevisiae S288C genomic DNA as a template for the reaction. A 719-bp fragment covering nucleotide positions +535 to +1253 also was generated, using oligonucleotide primers MSR3 and MSR4 (Fig. 1a). The 727-bp DNA fragment was inserted into the HindIII and XbaI sites of pUC18 (28), and the 719-bp fragment was inserted into the BamHI and EcoRI sites (an internal EcoRI restriction site decreased the fragment size to 483 bp). Finally, a BamHI-ClaI S. cerevisiae URA3-containing DNA fragment from plasmid YEp24 (8) was inserted into the BamHI and ClaI restriction sites present between the two MXR1 fragments, creating pJH121 (Fig. 1b). Thus, this plasmid carries a URA3-containing disruption cassette, which can be liberated by restriction digestion of pJH121 with PvuII (Fig. 1b). A 10-μg portion of purified disruption cassette DNA was used for transformation of S. cerevisiae M3750. Transformants were selected for uracil prototrophy, and 10 transformant yeast colonies were recovered. Analytical PCR (with primers MSR1 and MSR4) performed on genomic DNA from these clones confirmed the disruption of MXR1 (Fig. 1b and c). A DNA fragment of approximately 3 kb was amplified from all transformants, and a fragment of approximately 2 kb was amplified from the parental M3750 strain, the expected fragment sizes for disruptants and wild-type yeast, respectively. Disruptant JH465 (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 ura3 mxr1::URA3), (Fig. 1c) has been deposited at the American Type Culture Collection as ATCC 74452.

FIG. 1.

One-step gene disruption approach used for deletion of MXR1 in S. cerevisiae M3750 and for confirmation by PCR. (a) MXR1 region and strategy for PCR amplification of disruption cassette elements. (b) Construction of the disruption cassette and strategy used for disruption of MXR1. (c) PCR confirmation of the mxr1 disruptant. CHR. V, chromosome V.

Fermentations for assaying DMS production.

Approximately 106 cells from freshly grown plate cultures (YPD solidified with 2% agar) were inoculated into 200 ml of growth medium (SC, MP, or brewer’s wort with 2% glucose added) in 500-ml polypropylene Erlenmeyer flasks with fermentation locks. Fermentation continued for 7 days with shaking at 50 rpm, after which 10-ml samples were obtained through the side of the flasks with syringes and placed in evacuated blood sampling tubes (26). When the DMS content was above the standard curve of the assay (32 to 3,200 nM), samples were diluted and reassayed. The DMS content was measured by static headspace gas chromatography with sulfur-specific detection (Sievers 350B sulfur chemiluminiscense detector). Headspace sampling was performed with an automated headspace sampler (Perkin Elmer HS-40) with a 0.03-min injection time. The limit of detection for this method is 32 nM, and the standard deviation always below 10%.

DMSO reductase assay.

Purified recombinant yeast peptide MetSO reductase (Mxr1p) was kindly supplied by J. Moskovitz (19). The assay for DMSO reduction was modified from that of Bamforth (4), using a total assay volume of 10 ml (31 to 500 μM DMSO, 15 mM dithiothreitol, 400 μM NADPH, 200 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.0]) in sealed 25-ml crimp-top vials (Chrompack International B.V., Middelburg, The Netherlands). After the assay mixture was heated to 30°C for 20 min, the reaction was initiated by addition of 5 to 25 μg of pure Mxr1p with a microsyringe through the rubber stopper. After 30 or 60 min at 30°C, the headspace was sampled and the DMS content was measured as described above. All concentrations of DMSO substrate were assayed with or without enzyme. Assay mixture without DMSO served as a negative control. The Graflt program (Erithacus Software, Ltd.) was used to fit the data points and to calculate Vmax and Km for the enzyme.

Southern analysis.

Genomic yeast DNA was treated with restriction enzymes and separated on 1% agarose gels, transferred to Hybond-N membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech UK Ltd., Little Chalfont, United Kingdom), covalently bound to the membranes by UV irradiation, hybridized to 32P-labelled probes (random priming) at low stringency (50°C), and washed in 1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M sodium citrate) at the same temperature, essentially by the method of Sambrook et al. (23). Signals were recorded in a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.).

RESULTS

Construction of an mxr1 disruption strain.

No DNA sequences with significant sequence similarity to bacterial DMSO reductases (E. coli and Rhodobacter sphaeroides) were found within the ORFs of the genome of S. cerevisiae. However, the S. cerevisiae YER042w ORF product has high sequence similarity (31 to 42% amino acid identity) to known peptide MetSO reductases (PMSRs) from mammals, plants, fungi, and bacteria. Since the physiological function of the YER042w-encoded protein appears to be reduction of peptide MetSO (19), the name MXR1 (for “peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase 1”) is suggested for this gene. Our working hypothesis was that the same gene encodes the enzymatic activity responsible for reduction of MetSO to methionine and of DMSO to DMS during wort fermentation. To test this hypothesis, we inactivated the MXR1 gene in S. cerevisiae M3750 (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 ura3) by transformation with a disruption cassette, consisting of a functional URA3 gene surrounded by MXR1-proximal sequences (Fig. 1). Thus, a uracil-prototrophic disruption mutant in which 506 of the 555 nucleotides of the MXR1 ORF have been removed was created: JH465 (MATa SUC2 mal mel gal2 CUP1 ura3 mxr1::URA3).

Strain fitness and EthSO resistance of the mxr1 mutant.

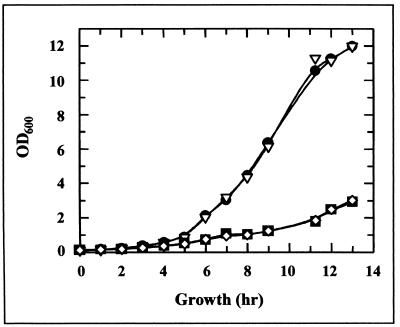

Strain M1997 is the Ura+ strain from which the ura3 strain M3750 was originally created, and it is therefore genetically and physiologically comparable to JH465, except for the mxr1 disruption in the latter. Precultures of strains M1997 and JH465 were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.15 in YPD or SD medium and monitored by observation of OD600 until early stationary phase. There was no difference between the growth abilities of the two strains in either medium (Fig. 2). The same strains were streaked onto solidified YPG (rich medium containing glycerol as the carbon source) and NF (minimal medium containing glycerol as the only carbon source) media. There was no apparent difference in colony size after 7 days of growth on YPG, while on NF there seemed to be a slight decrease in the colony size of strain JH465. The putative peptide MetSO reductase encoded by MXR1 appears not to be vital for growth under most laboratory conditions.

FIG. 2.

Growth in liquid culture (YPD or SD medium) of strains M1997 (wild type) and JH465 (mxr1Δ). ●, M1997, YPD; ▿, JH465, YPD; ■, M1997, SD; ◊, JH465, SD.

Ethionine sulfoxide (EthSO) is a putative analogue of MetSO. Strains M1997 and JH465 were both applied in water suspension onto an SC or an SC − Met (SC medium without methionine) plate, containing a preformed EthSO gradient (Fig. 3). After 4 days of growth, a clear inhibition zone of approximately 22 mm proximal to the filter strip could be seen with strain M1997, an inhibition which was antagonized when methionine was present in the plate (SC). Strain JH465 was clearly more resistant to EthSO on SC − met; very good growth was apparent as far as 17 mm from the filter strip, and significant growth was visible as far as 5 mm from the strip. Under the conditions chosen, Mxr1p probably converts EthSO into ethionine, a toxic methionine analogue (27). The same experiment was performed on MP plates (minimal medium containing proline as the only nitrogen source). Here, EthSO seemed more toxic to strain JH465, indicating that an alternative system for reduction of EthSO is induced under these conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Toxicity of EthSO to strains JH465 (mxr1Δ) and M1997 (wild type). A 200-μl volume of a 0.1 M dl-EthSO was applied to the filter strips, and 50 μl of the yeasts in water suspension was applied to the EthSO gradient. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 4 days.

Growth with MetSO as the sulfur source.

To assess the importance of the MXR1 gene product for utilization of MetSO as the sulfur source, we measured the growth of strains M1997 (wild type) and JH465 (mxr1Δ) with only methionine or MetSO as the sulfur source. The two yeast strains were inoculated in liquid B medium, propagated for 12 h with 100 μM dl-homocysteine, washed in water, and then starved for 16 h in B medium without any sulfur source, at a start density corresponding to an OD600 of 0.01. During this period, the OD600 increased to 0.2 to 0.3, probably due to the endogenous glutathione stock (12). At that point, each culture was divided into three subcultures. To one subculture was added 5 μM l-methionine, to the second was added 5 μM l-MetSO, and the third had no additions; the OD600 was monitored. After 9 h, the density of the wild-type culture (M1997) was 10% higher (standard deviation, 3%) with MetSO than with methionine while the density of the mxr1Δ strain (JH465) was 7% lower (standard deviation, 3%) with MetSO than with methionine. The standard deviations calculated were based on three repeated, identical experiments, and a Student t test showed the mean values for each strain under the two different growth circumstances to be significantly different from each other (5% significance level). Thus, in the wild-type yeast, MetSO is a better sulfur source than methionine while in the mxr1Δ mutant, MetSO is an inferior sulfur source.

Production of DMS from DMSO by strain JH465.

To assess the impact of the mxr1 deletion on the ability to convert DMSO to DMS in vivo, DMS formation by strains M1997 and JH465 during fermentation was measured. The yeasts were allowed to ferment either SD or MP medium with added DMSO or brewer’s wort. Large amounts of DMS were formed in the fermentations of SD medium with strain M1997 when DMSO was added, although only about 0.8% of the substrate was converted (Table 1). The same pattern could be seen with MP medium, but here about 1.4% was converted. Only for MP medium were there indications that JH465 could accomplish any conversion of DMSO at all, and then only to a very small degree. While numbers from the fermentations with synthetic media are sample values, the experiments were repeated with basically the same results (there was never any detectable DMS production from strain JH465 in ammonium medium). Brewer’s wort, having a natural DMSO content, was likewise inoculated with these strains, and the yeast was allowed to propagate under the same conditions as described above. Glucose (2%) was added to ensure good growth, since the strains of S. cerevisiae used (both of the mal genotype) do not ferment maltose very well. The final DMS content was 0.5 μM (standard deviation, 0.03 μM) after fermentation with strain M1997, whereas no DMS was detected after fermentation with strain JH465 (Table 1). No intrinsic DMS could be detected in this batch of wort, which means that less than 0.03 μM is present. All these data were the results of four identical experiments. I conclude that the mxr1Δ strain produces significantly less DMS from wort than does the wild-type strain; taken together, the results of the fermentation experiments strongly indicated that MXR1 encodes the enzymatic activity leading to DMS formation from DMSO.

TABLE 1.

Production of DMS from DMSO added to liquid growth media or already present in brewer’s wort

| Medium | DMS content (μM)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Produced by strain M1997 fermentation | Produced by strain JH465 fermentation | Intrinsic | |

| SD | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SD + DMSO (1.3 mM) | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| MP | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MP + DMSO (1.3 mM) | 18 | 0.1 | 0 |

| Brewer’s wort | 0.5 | NDa | ND |

ND, not detectable (limit of detection for the assay was 32 nM DMS).

DMSO-reducing capability of purified Mxr1p.

To obtain conclusive evidence of the DMSO-reducing capability of Mxr1p, I measured the formation of DMS from DMSO by purified recombinant Mxr1p. Formation of DMS was dependent on the presence of enzyme, and data points for DMS formation for five different concentrations of substrate could be fitted to a Michaelis-Menten curve with a Vmax value for DMSO reduction of 241 pmol of DMS formed min−1 (standard error, 26 pmol min−1) (at 23.7 nM enzyme) and a Km of 86 μM (standard error, 28 μM). From these values, kcat was calculated to be 0.02 s−1 and kcat/Km was calculated to be 200 M−1 s−1.

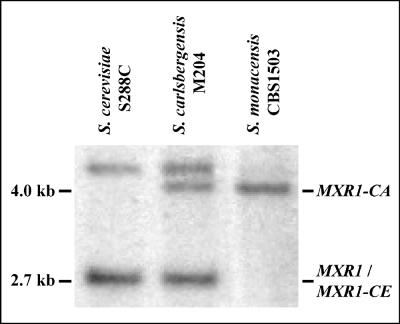

Occurrence of gene sequences similar to the S. cerevisiae MXR1 ORF in a production strain of S. carlsbergensis.

S. carlsbergensis (syn. of S. pastorianus) brewing yeast is a species hybrid, and two divergent but functionally equivalent alleles of a given gene are usually found in this yeast. One of these alleles is normally closely related to the corresponding gene from S. cerevisiae, and the other is normally related to the allele usually found in S. monacensis (syn. of S. pastorianus) (14, 20) (for a comprehensive description of the genetics of S. carlsbergensis brewing yeast, see reference 15). Southern analysis of BglII-digested genomic DNA from the S. carlsbergensis production strain M204, S. monacensis CBS1503, and S. cerevisiae S288C showed that homologous alleles were present in the brewing yeast (Fig. 4). A signal at 2.7 kb is seen in S. cerevisiae and at 4.0 kb in S. monacensis, while both signals are present in the production strain of S. carlsbergensis. A higher-molecular-weight signal seen in S. cerevisiae and S. carlsbergensis may represent a partial digestion of the MXR1 region. Since 2.7 kb is the expected size for an MXR1-containing BglII fragment (Fig. 1b) and since the 2.7-kb signals are still present on high-stringency Southern hybridizations with the same filter (data not shown), these signals represent MXR1 (S. cerevisiae) or a gene basically identical to this, MXR1-CE (S. cerevisiae-like MXR1 in S. carlsbergensis M204). The 4.0-kb signals were not seen in high-stringency Southern hybridizations (data not shown), and they putatively represent a gene somewhat diverged from but functionally analogous to MXR1. This putative gene (present in S. monacensis CBS1503 and S. carlsbergensis M204) was designated MXR1-CA (the S. carlsbergensis-specific MXR1 gene). Thus, S. carlsbergensis brewing yeast appears to possess two homologous genes for DMSO reduction, MXR1-CE and MXR1-CA.

FIG. 4.

Alleles of the MXR1 gene in S. cerevisiae S288C, S. carlsbergensis (syn. of S. pastorianus), and S. monacensis (syn. of S. pastorianus). BglII-digested genomic DNA was probed with S. cerevisiae MXR1.

DISCUSSION

Our results support the hypothesis of Moskovitz et al. (19), that reduction of peptide methionine sulfoxides is the physiological function of the polypeptide encoded by ORF YER042w, and we suggest the name MXR1 (for “peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase 1”) for this gene.

The peptide MetSO reductase encoded by MXR1 appears not to be essential for growth under several laboratory conditions. Even though deletion of MXR1 significantly decreases the value of MetSO as a sulfur source, this compound does satisfy the sulfur demand of strain JH465 to a large extent. This result indicates that MXR1 does not encode the sole enzymatic activity able to convert MetSO into methionine, a hypothesis supported by the fact that the putative MetSO analogue EthSO is still slightly poisonous for JH465. These results are consistent with those of Moskovitz et al. (19), who showed that a yeast strain with MXR1 disrupted retained 66% of its reductase activity against free MetSO. We have as yet no explanation for the observation that a wild-type yeast seems to grow better with MetSO than with methionine as the sulfur source.

Our experiments show that an mxr1 yeast disruption mutant is not able to metabolize DMSO into DMS. These results were seen both with synthetic media to which DMSO had been added and with brewer’s wort with a natural content of DMSO (Table 1), suggesting that MXR1 encodes the yeast enzyme responsible for DMSO reduction. Conclusive evidence for this function came from experiments showing DMSO reductase activity of purified Mxr1p enzyme, in agreement with earlier observations on the yeast enzyme (19a) and on E. coli and bovine peptide MetSO reductase (18). The Km was in the 100 μM range, indicating an intermediate affinity for the DMSO substrate. However, a very low maximal turnover number (approximately 0.02 s−1) accounts for the kcat/Km value of 200 M−1 s−1, which indicates a rather inefficient enzyme with respect to DMSO reduction. This result is consistent with earlier observations on a partially purified DMSO-reducing activity from yeast (4) and with the hypothesis that DMSO is not the physiological substrate of Mxr1p. The kinetics of DMSO reduction by Mxr1p could also explain the low substrate conversion ratio observed in earlier studies (1, 2) as well as in the present study (Table 1).

Mxr1p appears to be the only activity of significance when easily assimilated nitrogen (e.g., ammonium) is abundant, whereas an alternative system is active when only slowly assimilable nitrogen (e.g., proline) is present. This alternative system also could be responsible for the increased EthSO sensitivity on proline medium of the yeast devoid of Mxr1p activity and for the utilization of MetSO as a sulfur source in ammonium medium by the same strain. Thus, S. cerevisiae appears to contain more than one enzymatic system capable of reducing the related compounds MetSO, EthSO, and DMSO, and these systems seem to be more active when only slowly assimilable nitrogen is present (13).

The S. carlsbergensis brewing yeast appears to contain a gene almost identical to MXR1, i.e., MXR1-CE, and an analogous but diverged gene, MXR1-CA. Since an S. cerevisiae strain without MXR1 activity does not seem to lose viability or vitality under most laboratory conditions, and since only the Mxr1p-associated enzymatic system appears to be of significance for DMSO reduction, inactivation of these genes in brewing yeast could decrease the amount of DMS formed during beer production.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Susanne V. Bruun for technical assistance, Joan Winterberg and Lene M. Bech for DMS analyses, Pia F. Johannesen and Claes Gjermansen for critical reading of the manuscript, and Kjeld Olesen for suggestions and help with enzyme kinetics. Jakob Moskovitz is sincerely thanked for supplying yeast peptide MetSO reductase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anness B J. The reduction of dimethyl sulphoxide to dimethyl sulphide during fermentation. J Inst Brew. 1980;86:134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anness B J, Bamforth C W. Dimethyl sulphide—a review. J Inst Brew. 1982;88:244–252. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anness B J, Bamforth C W, Wainwright T. The measurement of dimethyl sulphoxide in barley and malt and its reduction to dimethyl sulphide by yeast. J Inst Brew. 1979;85:346–349. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamforth C W. Dimethyl sulphoxide reductase of Saccharomyces spp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1980;7:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bamforth C W, Anness B J. Dimethyl sulphoxide reduction by yeast. Soc Gen Microbiol Q. 1979;6:160. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamforth C W, Anness B J. The role of dimethyl sulphoxide reductase in the formation of dimethyl sulphide during fermentations. J Inst Brew. 1981;87:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black S, Harte E M, Hudson B, Wartofsky L. A specific enzymatic reduction of l (−) methionine sulfoxide and a related nonspecific reduction of disulfides. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:2910–2916. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botstein D, Falco S C, Stewart S E, Brennan M, Scherer S, Stinchcomb D T, Struhl K, Davis R W. Sterile host yeasts (SHY): a eukaryotic system of biological containment for recombinant DNA experiments. Gene. 1979;8:17–24. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherest H, Surdin-Kerjan Y. Genetic analysis of a new mutation conferring cysteine auxotrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: updating of the sulfur metabolism pathway. Genetics. 1992;130:51–58. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickenson C J. Cambridge Prize Lecture. Dimethyl sulphide—its origin and control in brewing. J Inst Brew. 1983;89:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickenson C J, Anderson R G. European Brewery Convention, Proceedings of the 18th Congress, Copenhagen, 1981. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press Ltd., Information Printing Ltd.; 1981. The relative importance of S-methylmethionine and dimethyl sulphoxide as precursors of dimethyl sulphide in beer; pp. 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elskens M T, Jaspers C J, Penninckx M J. Glutathione as an endogenous sulphur source in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:637–644. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-3-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson R M, Large P J. The influence of assimilable nitrogen compounds in wort on the ability of yeast to reduce dimethyl sulphoxide. J Inst Brew. 1985;91:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen J, Kielland-Brandt M C. Saccharomyces carlsbergensis contains two functional MET2 alleles similar to homologues from S. cerevisiae and S. monacensis. Gene. 1994;140:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kielland-Brandt M C, Nilsson-Tillgren T, Gjermansen C, Holmberg S, Pedersen M B. Genetics of brewing yeasts. In: Wheals A E, Rose A H, Harrison J S, editors. The yeasts. 2nd ed. Vol. 6. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press, Ltd.; 1995. pp. 223–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leemans C, Dupire S, Macron J-Y. European Brewery Convention, Proceedings of the 24th Congress, Oslo, 1993. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press, Oxford University Press; 1993. Relation between wort DMSO and DMS concentration in beer; pp. 709–716. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meilgaard M. Flavor chemistry of beer. II. Flavor and threshold of 239 aroma volatiles. MBAA Tech Q. 1975;12:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moskovitz J, Weissbach H, Brot N. Cloning and expression of a mammalian gene involved in the reduction of methionine sulfoxide residues in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2095–2099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moskovitz J, Berlett B S, Poston J M, Stadtman E R. The yeast peptide-methionine sulfoxide reductase functions as an antioxidant in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9585–9589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Moskovitz, J. Personal communication.

- 20.Pedersen M B. DNA sequence polymorphisms in the genus Saccharomyces. IV. Homoeologous chromosomes III of Saccharomyces bayanus, S. carlsbergensis, and S. uvarum. Carlsberg Res Commun. 1986;51:185–202. doi: 10.1007/BF02904408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porqué P G, Baldesten A, Reichard P. The involvement of the thioredoxin system in the reduction of methionine sulfoxide and sulfate. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:2371–2374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothstein R. Targetting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiestl R H, Gietz R D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sigsgaard P, Rasmussen J N. Screening of the brewing performance of new yeast strains. J Am Soc Brew Chem. 1985;43:104–108. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer R A, Johnston C G, Bedard D. Methionine analogs and cell division regulation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:6083–6087. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.12.6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zinder S H, Brock T D. Dimethyl sulphoxide reduction by micro-organisms. J Gen Microbiol. 1978;105:335–342. doi: 10.1099/00221287-105-2-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]