Abstract

A patient's likelihood to recommend a hospital is used to assess the quality of their experience. This study investigated whether room type influences patients’ likelihood to recommend Stanford Health Care using Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey data from November 2018 to February 2021 (n = 10,703). The percentage of patients who gave the top response was calculated as a top box score, and the effects of room type, service line, and the COVID-19 pandemic were represented as odds ratios (ORs). Patients in private rooms were more likely to recommend than patients in semi-private rooms (aOR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.16–1.51; 86% vs 79%, p < .001), and service lines with only private rooms had the greatest increases in odds of a top response. The new hospital had significantly higher top box scores than the original hospital (87% vs 84%, p < .001), indicating that room type and hospital environment impact patients’ likelihood to recommend.

Keywords: room type, likelihood to recommend, patient experience

Introduction

A patient's likelihood to recommend a hospital to their friends and family is an important metric in assessing their overall hospital experience and quality of care.1 Private rooms offer potential advantages for patients over semi-private rooms, including increased privacy and improved communication with physicians.2,3 However, semi-private rooms, which are shared among 2 or 3 patients, remain a viable care environment and are sometimes necessary with many hospitals at overcapacity.4 Previous studies have found that a patient's room preference depends on their personal priorities.5 For instance, private rooms allow for more privacy, while semi-private rooms offer opportunities for socialization.6,7 It is currently unclear whether a patient's room type significantly impacts their likelihood to recommend. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of room type, service line, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on patients’ likelihood to recommend a hospital to others.

Methods

This retrospective study included patients in all non-ICU units across both hospitals at Stanford Health Care (SHC; n = 10,703). Patients discharged from November 2018 to February 2021 were asked to complete the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey. The original hospital (300P) contains both semi-private and private rooms, while the new hospital (500P) that opened in November 2019 contains only private rooms. Patients are assigned to a unit and room to optimize colocation within each service line. One medicine unit in the new hospital began exclusively treating COVID-19 patients on March 20, 2020.

The percentage of patients who responded “Definitely yes” when asked “Would you recommend this hospital to your friends and family?” was calculated as the likelihood to recommend top box score. The other possible responses to this question were “Definitely no,” “Probably no,” and “Probably yes.” A chi-squared test was used to identify statistically significant differences in top box scores between patients in semi-private and private rooms across both hospitals and within each unit. Differences between patients in private rooms in the original and new hospitals were also analyzed. To assess the overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient experience, top box scores of patients across both hospitals discharged before and after the opening of the COVID-19 unit were compared. COVID-19 patients and non-COVID-19 patients in the same room type and hospital were also compared.

A multivariate regression was performed to estimate the effects of room type, service line, and admission date (before or after the COVID-19 unit opened) on patients’ likelihood to recommend SHC. The association of a top response was represented as an unadjusted odds ratio (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (aOR). A significance level of .05 was used for all statistical tests.

Results

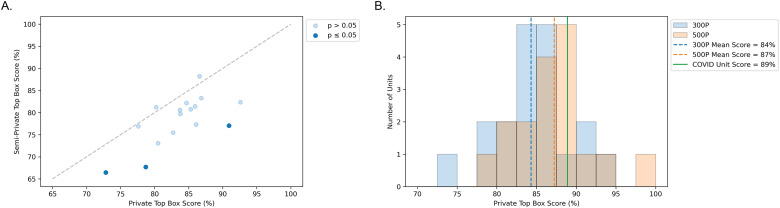

The number of patients in each room type was determined for each service line, as well as across both hospitals before and after the COVID-19 unit opened (Table 1). Across both hospitals, patients in private rooms were more likely to recommend SHC than patients in semi-private rooms, adjusting for the service line and admission date (aOR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.16–1.51; 86% top box score for private rooms vs 79% for semi-private rooms, p < .001). Out of 17 non-ICU units containing both room types, one medicine unit (n = 347, 79% vs 68%, p = .028) and two surgery units (n = 519, 86% vs 77%, p = .013; n = 179, 91% vs 77%, p = .049) had significantly higher top box scores for private rooms compared to semi-private rooms within the same unit (Figure 1A). Twelve other units also had higher top box scores for private rooms but did not show significant differences due to smaller sample sizes.

Table 1.

Number of Patients by Room Type, and Odds Ratios Estimating the Effects of Room Type, Service Line, and Admission Date on Likelihood to Recommend (n = 10,703).

| Number of patients (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-private rooms | Private rooms | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Room type | Semi-private (reference) | - | - | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Private | - | - | 1.54 (1.38–1.70)*** | 1.32 (1.16–1.51)*** | |

| Service line | Medicine (reference) | 552 (35.34%) | 1010 (64.66%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Orthopedics | 0 (0%) | 603 (100%) | 2.28 (1.71–3.04)*** | 2.02 (1.51–2.71)*** | |

| Cardiology | 0 (0%) | 1143 (100%) | 2.18 (1.75–2.73)*** | 1.94 (1.54–2.44)*** | |

| Neurosurgery | 0 (0%) | 467 (100%) | 1.67 (1.25–2.24)*** | 1.49 (1.11–2.00)** | |

| Oncology | 119 (32.69%) | 245 (67.31%) | 1.40 (1.03–1.90)* | 1.39 (1.02–1.88)* | |

| Surgery | 1427 (70.71%) | 591 (29.29%) | 1.08 (0.92–1.27) | 1.20 (1.01–1.42)* | |

| Pulmonary/respiratory | 138 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 1.40 (0.87–2.25) | 1.24 (0.77–2.00) | |

| Neurology | 204 (64.35%) | 113 (35.65%) | 1.01 (0.75–1.36) | 1.10 (0.81–1.49) | |

| Admission date | Pre-COVID-19 (reference) | 3493 (53.31%) | 3059 (46.69%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Post-COVID-19 | 69 (1.66%) | 4082 (98.34%) | 1.37 (1.23–1.52)*** | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | |

*: p ≤ .05; **: p ≤ .01; ***: p ≤ .001.

Figure 1.

Comparison of likelihood to recommend top box scores by room type and hospital. Private rooms had significantly higher top box scores than semi-private rooms, and private rooms in the new hospital (500P) had significantly higher top box scores than private rooms in the original hospital (300P). (A) Likelihood to recommend top box scores for non-ICU units containing both room types. (B) Distribution of private room likelihood to recommend top box scores for non-ICU units in 300P (blue) and 500P (orange). Vertical lines indicate the mean score for units in 300P (blue), mean score for units in 500P (orange), and score for the COVID-19 unit (green).

The service line was also associated with differences in patients’ likelihood to recommend SHC to others. Compared to medicine, the odds of a top response significantly increased in orthopedics (aOR: 2.02; 95% CI: 1.51–2.71), cardiology (aOR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.54–2.44), neurosurgery (aOR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.11–2.00), oncology (aOR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.02–1.88), and surgery (aOR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.01–1.42). However, pulmonary/respiratory and neurology did not have significant differences compared to medicine.

The hospital environment also impacted patients’ likelihood to recommend SHC. Patients in private rooms in the new hospital were more likely to recommend SHC than patients in private rooms in the original hospital (87% vs 84%, p < .001; Figure 1B).

Notably, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic did not significantly affect patients’ likelihood to recommend SHC. Across both hospitals, there was no significant difference in odds of a top response from patients discharged before and after the opening of the COVID-19 unit. In addition, there was no significant difference in patients’ likelihood to recommend SHC when comparing COVID-19 patients to non-COVID-19 patients in the same room type and hospital.

Discussion

This study fills a critical gap in the literature by being the first to evaluate the impact of room type and service line on patients’ likelihood to recommend a hospital to others. Previous studies have found that patients’ interactions with nurses and physicians have the greatest impact on their likelihood to recommend a hospital to others.8–11 Communication with hospital staff is especially important in emergency department settings. Patients who were called back after discharge were more likely to recommend regardless of wait time, length of stay, or triage class.12 In addition, patients who were kept informed by a nurse or physician while in the examination room were more likely to recommend.13 Another study found that technical aspects of care, such as hospital equipment, clinical competence, and outcome of treatment, were also associated with patients’ likelihood to recommend.14

This study found that patients in private rooms were significantly more likely to recommend SHC than patients in semi-private rooms, regardless of service line or admission date. Furthermore, service lines with only private rooms (orthopedics, cardiology, neurosurgery) had the greatest increases in odds of a top response compared to medicine, which has both semi-private and private rooms. The 2 service lines that did not show significant differences in odds of a top response compared to medicine (pulmonary/respiratory and neurology) had most patients in semi-private rooms, suggesting that the disparity in top box scores across service lines could be driven by their different distributions of room types.

Furthermore, private rooms in the new hospital had a significantly higher top box score than private rooms in the original hospital, indicating that the hospital environment also plays an important role in patient satisfaction. Other studies have also found that improved hospital environments are associated with higher likelihood to recommend scores. For instance, patients who were exposed to an arts-enhanced environment were more likely to recommend the hospital to others.15

When evaluating each unit, private room top box scores for units in the original hospital ranged from 73% to 93%, while units in the new hospital ranged from 79% to 100%. However, the overall difference in top box scores between the two hospitals was less significant than the difference between room types, suggesting that a patient's room has a greater impact on their experience than the overall hospital environment.

Limitations

Given this survey's retrospective design and response rate of 20%, the results may not be generalizable to all patients at SHC and other institutions. In addition, there are factors outside the scope of this study that impact patient experience, such as communication with hospital staff or meals. However, this study includes a large and diverse patient cohort, providing evidence that there is a significant relationship between a patient's room type and their likelihood to recommend a hospital to others.

Conclusions

These results can be used to inform quality improvement initiatives to maximize patient experience. Since different service lines have different distributions of room types, it is essential to analyze patient experience by unit or service line instead of the whole hospital. In addition, different patient experience benchmarks should be used for different service lines to ensure that discrepancies in performance are not primarily caused by room type. Future studies should further investigate the impact of a patient's room type and service line on their hospital experience to ensure that all patients receive high-quality care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Michael Yeung for providing the data for this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Ella Atsavapranee https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5824-4521

References

- 1.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e001570. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maben J, Griffiths P, Penfold C, et al. One size fits all? Mixed methods evaluation of the impact of 100% single-room accommodation on staff and patient experience, safety and costs. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(4):241-56. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van de Glind I, van Dulmen S, Goossensen A. Physician-patient communication in single-bedded versus four-bedded hospital rooms. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):215-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verderber S, Todd LG. Reconsidering the semiprivate inpatient room in U.S. Hospitals . HERD. 2012;5(2):7-23. doi: 10.1177/193758671200500202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Pukszta M. Private rooms, semi-open areas, or open areas for chemotherapy care: perspectives of cancer patients, families, and nursing staff. Heal Environ Res Des J. 2018;11(3):94-108. doi: 10.1177/1937586718758445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrlander W, Ali F, Chretien KC. Multioccupancy hospital rooms: veterans’ experiences and preferences. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):22-7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nahas S, Patel A, Duncan J, Nicholl J, Nathwani D. Patient experience in single rooms compared with the open ward for elective orthopaedic admissions. Musculoskeletal Care. 2016;14(1):57-61. doi: 10.1002/msc.1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senti J, LeMire SD. Patient satisfaction with birthing center nursing care and factors associated with likelihood to recommend institution. J Nurs Care Qual. 2011;26(2):178-185. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3181fe93e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer FA, Tuttas C. HCAHPS: nursing’s moment in the sun. Nurse Lead. 2008;6(5):48-51. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2008.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahamson K, Fulton BR, Sternke EA, Davila H, Morgan KH. The resident experience: influences upon the likelihood to recommend a nursing home to others. Seniors Hous Care J. 2017;25(1):85–95.. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=gnh&AN=EP130697628&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinkenberg WD, Boslaugh S, Waterman BM, et al. Inpatients’ willingness to recommend: a multilevel analysis. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36(4):349-58. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182104e4a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guss DA, Gray S, Castillo EM. The impact of patient telephone call after discharge on likelihood to recommend in an academic emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(4):560-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.11.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson MB, Castillo EM, Harley J, Guss DA. Impact of patient and family communication in a pediatric emergency department on likelihood to recommend. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(3):243-6. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182494c83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng SH, Yang MC, Chiang TL. Patient satisfaction with and recommendation of a hospital: effects of interpersonal and technical aspects of hospital care. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2003;15(4):345-55. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slater JK, Braverman MT, Meath T. Patient satisfaction with a hospital’s arts-enhanced environment as a predictor of the likelihood of recommending the hospital. Arts Heal. 2017;9(2):97-110. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2016.1185448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]