Abstract

Background:

Hyposmia is a characteristic of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) whereas progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) typically has normal sense of smell. However, there is a lack of pathologically confirmed data.

Objective:

To study hyposmia in pathologically confirmed PSP patients and compare to PD patients and non-degenerative controls.

Methods:

We studied autopsied subjects in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders who had antemortem olfactory testing and a neuropathological diagnosis of either PD, PSP, or control.

Results:

There were 281 cases included in this study. Those with neuropathologically confirmed PSP (N=24) and controls (N=174) had significantly better sense of smell than those with PD (N=76). While most PSP patients had normal olfaction, there were some with hyposmia, resulting in an overall reduced sense of smell in PSP compared to controls. The sensitivity of having PSP pathologically in those presenting with parkinsonism and normosmia was 93.4% with specificity of 64.7%. Cases with both PSP and PD pathologically had reduced sense of smell similar to PD alone (N=7). Hyposmic PSP patients had significantly higher Lewy body burden not meeting criteria for additional PD/DLB diagnosis.

Conclusion:

Pathologically confirmed PD had reduced olfaction compared with PSP or controls. In the setting of parkinsonism in this sample, the presence of normosmia had high sensitivity for PSP. Hyposmia in PSP suggests the presence of additional Lewy body pathology.

Keywords: UPSIT, Parkinson’s disease, pathology, brain bank

Introduction

Previous studies have shown that hyposmia is a feature of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Hyposmia is likely to begin at prodromal disease stages as it is present in subjects with incidental Lewy body disease (ILBD) and often predates the appearance of motor features.(1–8) On the other hand, patients with clinically determined Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) have been reported to have normal olfaction.(9–13) However, there is a lack of studies done with pathological confirmation of disease state.

We studied patients with PSP in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND) who came to autopsy, comparing them to controls and patients with PD.

Methods

This study was conducted as part of the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND) by the Arizona Parkinson Disease Consortium/Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program (BBDP).(14, 15) All subjects in the BBDP had signed informed consent approved by Banner Sun Health Research Institute IRB and were followed prior to death with annual standardized medical, movement, and cognitive assessments. The database was queried for autopsied cases with olfactory testing who had a clinicopathologic diagnosis of either PD, PSP or control (no neurodegenerative disorder).

All cases analyzed completed the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), an olfactory test that requires subjects to identify, by multiple-choice, 40 odorants microencapsulated on “scratch and sniff” labels.(16) The UPSIT was scored using standard procedures (scores 0 to 40). The battery of UPSIT testing was added to the BBDP in June 2002.

Subjects were autopsied and received a final diagnosis based on clinicopathologic correlation as previously described.(14) Clinically probable PD was defined as those with two of three cardinal features (rest tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity) of PD with one of them being bradykinesia combined with sustained response to levodopa. Possible PD were those having at least 2 of 3 clinical features with either no treatment as yet for PD or inadequate trial of medication. Suspect PD had just one clinical sign. Parkinsonism NOS (Park NOS) was used for who did not respond to dopaminergic drugs, did not progress over 5 years or had parkinsonism in the setting of other conditions such as advanced Alzheimer’s dementia. Clinical PSP was defined according to NINDS criteria.(17) The presence of dementia was determined by annual case conference prior to death. PD was defined clinicopathologically as having clinical parkinsonism with alpha-synuclein immunoreactive neuronal inclusions (Lewy bodies) and neuronal loss in the substantia nigra pars compact (SNpc). PSP was confirmed using standard neuropathological criteria with accumulation of tau protein in astrocytes (“tufted astrocytes”) and neurons (“tangles”) with neuropil threads in typical basal ganglia and brainstem locations.(18, 19) Lewy body density score is a semi-quantitative score (0–4) for each brain region with the total being the sum of all regions.

Statistics

Continuous variable differences were compared among groups using ANOVA F-test or Kruskal-Wallis test when appropriate. Categorical variable differences were compared using Chi squared test. UPSIT score were compared among the four groups using ANCOVA method adjusting for age at smell test and sex. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons between groups were further conducted and Bonferroni method was used to adjusted for multiple comparisons. ROC analysis was conducted was used to investigate how UPSIT can predict final clinicopathologically-diagnosed PD cases (including PD+PSP cases) and final clinicopathologically-diagnosed PSP with parkinsonism. Youden index was used to choose the optimum cut-off point to differentiate these two groups. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated based on the optimum cut-off point.

Results

There were 485 cases with a neuropathological diagnosis included for initial analysis. These included PSP (n= 52), PD (n = 173) PSP and PD (n = 10), and 250 controls. After exclusion of those without antemortem olfactory testing, 281 remained for analysis.

Table 1 shows a comparison of the demographics and clinical characteristics by final clinicopathological diagnosis: PSP only, PD only, PSP + PD and controls. Cases with a final clinicopathological diagnosis of PD (with or without PSP) had significant younger age at death compared to PSP-only patients and controls (p<.001). Patients with final clinicopathological diagnoses of PD or PSP had significantly higher percentages of males compared to controls (p=0.001). Demographics of those without a smell test were similar (data not presented). Only 5/24 PSP-only patients were clinically diagnosed with PSP prior to death with 7 having no diagnosis of parkinsonism. Presence of dementia at death was high in all groups, 62.5% in PSP-only, 54.5% in PD-only and 57.1% in PSP+PD. Controls, by definition, were not demented.

Table 1.

is the demographics and clinical characteristic for the 281 patients who had smell test divided by their final clinicopathological diagnosis.

| Table 1. Demographics and Clinical Characteristics for patients who had smell test by final clinicopath dx | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final clinicopath Diagnosis | ||||||

| PSP only | PD only | PSP + PD | Control | Total | P-value | |

| (N=24) | (N=76) | (N=7) | (N=174) | (N=281) | ||

|

Death Age (y)

Mean (SD) |

86.6 (8.6) | 82.0 (7.3) | 83.9 (3.9) | 88.3 (6.8) | 86.3 (7.5) | <0011 |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (29.2%) | 20 (26.3%) | 2 (28.6%) | 89 (51.1%) | 118 (42.0%) | 0.0012 |

|

Education (y)

Mean (SD) |

16.4 (3.1) | 15.3 (2.9) | 16.0 (3.3) | 15.0 (2.7) | 15.2 (2.8) | 0.2403 |

| FD-M Parkinsonism, n (%) | <.0012 | |||||

| No | 7 (29.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 164 (94.3%) | 171 (60.9%) | |

| Suspect PD/Possible PD | 2 (8.3%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.7%) | 4 (1.4%) | |

| Probable PD | 2 (8.3%) | 66 (86.8%) | 6 (85.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | 75 (26.7%) | |

| Parkinsonism NOS | 8 (33.3%) | 7 (9.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.3%) | 19 (6.8%) | |

| PSP | 5 (20.8%) | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (2.5%) | |

| FD Dementia, n (%) | 15 (62.5%) | 41 (53.9%) | 4 (57.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 60 (21.4%) | <.0012 |

| Time between smell test and expiration date | 1307.0 (1154.0) | 1059.1 (787.1) | 1037.1 (618.1) | 923.2 (745.2) | 995.6 (799.6) | 0.2983 |

| UPSIT (0–40) | <.0011 | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 21.9 (9.4) | 13.8 (5.3) | 16.9 (4.5) | 26.8 (6.8) | 22.6 (8.7) | |

| Median (IQR) | 25 (12, 29) | 13 (10, 17) | 15 (14, 22) | 29 (22, 31) | 24 (15, 30) | |

| Range | 6.0, 36.0 | 5.0, 30.0 | 12.0, 24.0 | 6.0, 38.0 | 5.0, 38.0 | |

ANOVA F-test p-value;

Chi-Square p-value;

Kruskal-Wallis p-value;

PD=Parkinson’s disease; PSP = Progressive supranuclear palsy; NOS= not otherwise specified; SD= standard deviation; IQR= interquartile range.

The last UPSIT score, compared using ANCOVA and post-hoc paired significance tests, showed those with PD (with or without PSP) had significantly lower UPSIT scores compared to PSP-only patients or controls (p<0.001). PSP only was also significantly different than controls (p<0.001). There were no significant differences between PSP+PD and PD only (p=0.966) or PSP+PD and PSP only (p=0.290). The latter may be due to small sample size in this group.

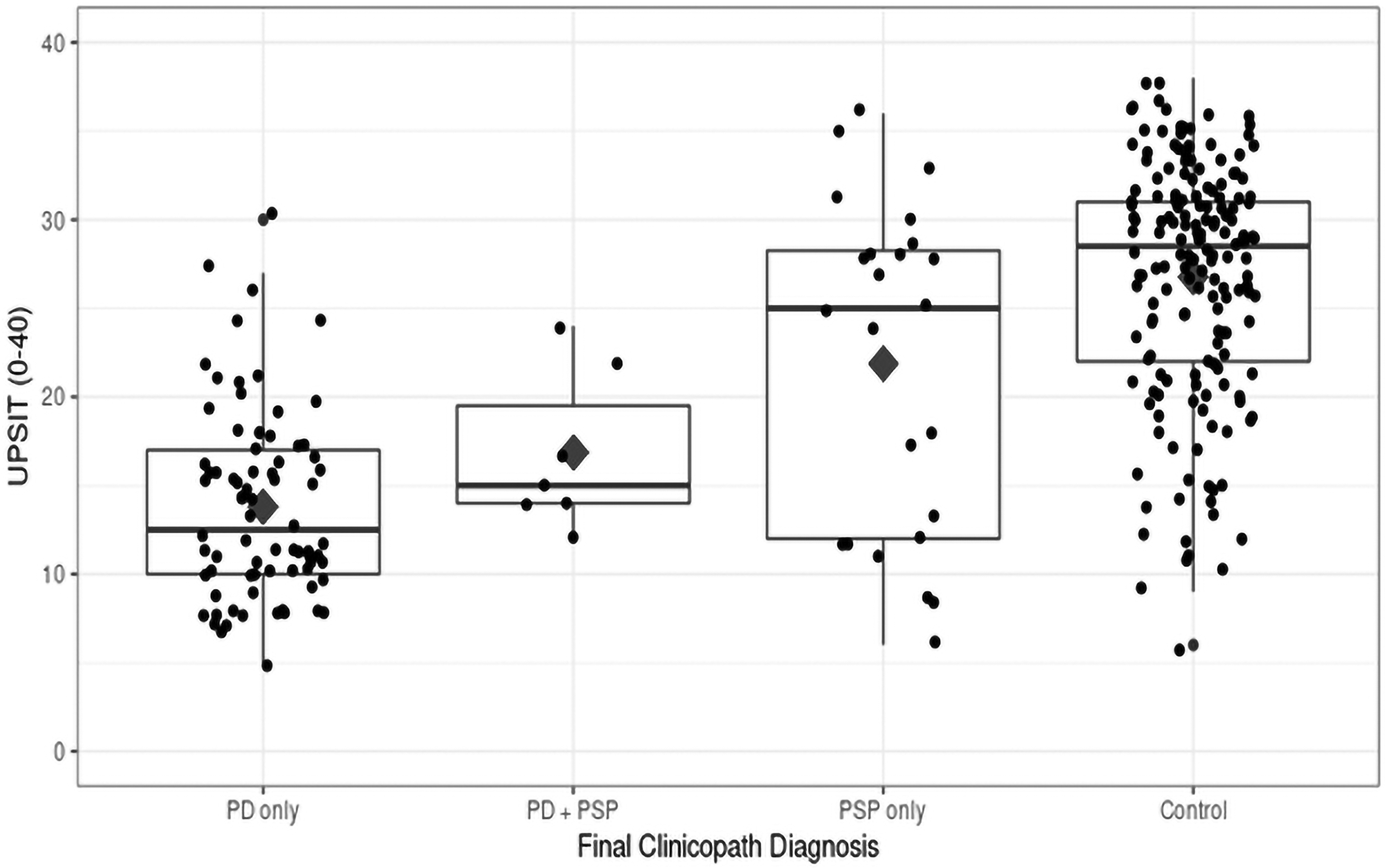

To better illustrate the UPSIT distribution among the four groups, the UPSIT dot plots by final clinicopathological diagnosis are presented in the Figure 1. The Youden index of 19 was chosen as the optimum cut-off score to predict PD and non-PD cases (PSP and controls). The sensitivity of this cut-off in predicting PD pathologically was 84.5% with specificity of 81.4%.

Figure 1:

UPSIT dotplots by final diagnosis group

The 24 PSP-only cases had a bimodal distribution of UPSIT scores, one at 12 (close to PD patients’ UPSIT scores) and one at 30 (close to control patients’ UPSIT scores). Thus, there was no optimal Youden Index to distinguish PSP from controls.

Among the pathologically proven PSP cases only 5 (20.8%) met clinical criteria for PSP while 7 had no signs of parkinsonism. The other 12 cases had signs of parkinsonism with two meeting criteria for clinically probable PD. In those cases with both PSP and PD pathologically, the clinical features were mostly that of Probable PD with only one of 7 having been diagnosed with PSP only prior to death. For this group of PSP presenting with parkinsonism (N=17), mean UPSIT was 23.3 (SD 9.6) compared with 13.8 (SD 5.3) for PD only. ROC analysis showed an optimal cut off of 22. This resulted in a sensitivity of 93.4% with specificity of 64.7% for PSP pathologically.

The UPSIT scores of the 24 PSP-only cases can be divided into UPSIT <=18 and UPSIT >= 24 (there were no UPSIT scores in between). Ten patients had reduced UPSIT, the remainder had an UPSIT >= 24. There were no significant differences between these groups for demographics or clinical characteristics (including UPDRS III, presence of down gaze palsy, square wave jerks). The low UPSIT group had more dementia cases (80% compared to 50%) but this is not significant due to the small sample size (p=0.21). Parkinsonism was seen in 60% (versus 78.6%) of low UPSIT PSP. We further examined neuropathological findings in this hyposmic PSP group. There was no difference in overall tau burden in these subjects. The patients with lower UPSIT score had significantly higher sum of Lewy body density score compared to patients with upper UPSIT score (median (IQR): 3 (0 to 18) vs. 0 (0, 0), p=0.032).

Discussion:

The primary finding of this study is the strong effect of pathologically-proven PD on reduction of olfaction as measured by the UPSIT. Cases of PSP have a near normal sense of smell as a group although some cases had hyposmia. Those subjects with both PD and PSP pathologically have UPSIT scores similar to PD alone.

The presence of hyposmia in the setting of IPD has been well described. (2, 4, 6) Most, if not all patients with PD have reduced or absent sense of smell which is often present prodromally and seems to remain static across the disease course.(1, 3, 7) Underlying pathology of hyposmia is almost certainly at least partially due to early involvement of the olfactory bulb in the central nervous system (20), although the amygdala also contributes to the subjective sense of smell(21), and α-synuclein pathology is almost always severe in both of these regions. Patients with Parkinson’s disease are often aware of reduced sense of smell but it is better confirmed by objective testing.(22)

Most pathologically confirmed cases of PSP appear to have an age-appropriate normal sense of smell. Only 10 of the 24 PSP cases had hyposmia similar to PD. In further analysis of this population, there did not seem to be any other discriminating clinical features other than the presence of cognitive impairment. Neuropathology suggests that hyposmia might be driven by Lewy body pathology not meeting criteria for Parkinson’s or dementia with Lewy bodies. This study was limited by having had only 5 PSP cases with a clinical diagnosis of PSP. Yet that is also a strength as PSP clearly is underdiagnosed clinically and using olfactory testing may improve diagnosis. In this study, 8/12 subjects with parkinsonian features prior to death and PSP pathologically had UPSIT score similar to controls suggesting this may be a useful predictive clinical sign.

A finding that has not been described before is the impact of co-existing pathologies. The cases that met neuropathological criteria for both PD and PSP had hyposmia consistent with those with PD alone. These patients mostly had PD clinically but there was one who had PSP clinically. Therefore, this finding could be quite clinically useful as a patient with a classic PSP phenotype with abnormal sense of smell might be suspected to have concomitant alpha-synuclein pathology.

In summary, using objective smell testing, the presence of hyposmia is useful in predicting PD pathologically whereas having normal olfaction in the setting of clinical parkinsonism suggests the presence of PSP pathologically.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026) the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. The authors thank the participants of the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders.

Shill: Funding received from NIH, Arizona Biomedical Research Commission and Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Zhang: None

Driver-Dunckley: None

Mehta: Arizona Biomedical Research Commission

Adler: Funding received from NIH, Arizona Biomedical Research Commission, Mayo Foundation and Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Beach: Funding received from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24

NS072026), National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610), Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002), Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (no grant number).

Funding sources for study.

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026) the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001) and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

(8) Authors’ Roles

Shill: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2C, 3A

Zhang: 1C, 2A, 2B, 3B

Driver-Dunckley: 1C, 2C, 3B

Mehta: 1C, 2C, 3B

Adler: 1A, 1C, 2C, 3B

Beach: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

(9) Financial Disclosures of all authors (for the preceding 12 months)

Shill:

Stock Ownership in medically-related fields: None

Intellectual Property Rights None

Consultancies: None

Expert Testimony None

Advisory Boards: Acorda, Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Employment: Dignity Health

Partnerships None

Contracts None

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals

Royalties None

Grants: NIH, Barrow Neurological Foundation, Impax Laboratories, Biogen, Sunovion and US World Meds

Other: None

Zhang:

Stock Ownership in medically-related fields None

Intellectual Property Rights: None

Consultancies None

Expert Testimony None

Advisory Boards None

Employment: Mayo Clinic Arizona Partnerships None

Contracts None

Honoraria None

Royalties None

Grants: None

Other: None

Driver-Dunckley:

Stock Ownership in medically-related fields None

Intellectual Property Rights: None

Consultancies None

Expert Testimony None

Advisory Boards None

Employment Mayo Clinic Arizona

Partnerships None

Contracts None

Honoraria None

Royalties None

Grants: Clinical drug studies for PSP with Abbvie, Biogen, UCB Pharma Other

Mehta:

Stock Ownership in medically-related fields None

Intellectual Property Rights: None

Consultancies CNS Ratings, Adamas Pharmaceuticals, Abbott

Expert Testimony None

Advisory Boards None

Employment: Mayo Clinic Arizona

Partnerships None

Contracts None

Honoraria None

Royalties None

Grants: Arizona Biomedical Research Commission, International Essential Tremor Foundation (IETF) Grant, Eli Lilly, Pharma2B and Neuraly.

Other

Adler:

Stock Ownership in medically-related fields: None

Intellectual Property Rights: None

Consultancies- Amneal, Easai, Jazz, Neurocrine, Cionic Expert Testimony: None

Advisory Boards: None

Employment: Mayo Clinic Arizona

Partnerships: None

Contracts: None

Honoraria: None

Royalties: None

Grants: Michael J. Fox Foundation, NINDS

Beach:

Stock Ownership in medically-related fields: Vivid Genomics, Inc.

Intellectual Property Rights: None

Consultancies: Vivid Genomics, Prothena Biosciences

Expert Testimony: None

Advisory Boards: Vivid Genomics

Employment: Banner Sun Health Research Institute

Partnerships: None

Contracts: Research contract with Avid Radiopharmaceuticals

Honoraria: Mayo Clinic Jacksonville

Royalties: None

Grants: National Institute on Aging, National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke,

Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, Arizona Department of Health Services Other: None

References

- 1.Ponsen MM, Stoffers D, Booij J, van Eck-Smit BL, Wolters E, Berendse HW. Idiopathic hyposmia as a preclinical sign of Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(2):173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyamoto T, Miyamoto M, Iwanami M, Hirata K, Kobayashi M, Nakamura M, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med. 2010;11(5):458–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siderowf A, Jennings D, Eberly S, Oakes D, Hawkins KA, Ascherio A, et al. Impaired olfaction and other prodromal features in the Parkinson At-Risk Syndrome Study. Mov Disord. 2012;27(3):406–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKinnon J, Evidente V, Driver-Dunckley E, Premkumar A, Hentz J, Shill H, et al. Olfaction in the elderly: a cross-sectional analysis comparing Parkinson’s disease with controls and other disorders. Int J Neurosci. 2010;120(1):36–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach TG, Adler CH, Zhang N, Serrano GE, Sue LI, Driver-Dunckley E, et al. Severe hyposmia distinguishes neuropathologically confirmed dementia with Lewy bodies from Alzheimer’s disease dementia. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adler CH, Beach TG, Zhang N, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, Caviness JN, et al. Unified Staging System for Lewy Body Disorders: Clinicopathologic Correlations and Comparison to Braak Staging. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2019;78(10):891–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driver-Dunckley E, Adler CH, Hentz JG, Dugger BN, Shill HA, Caviness JN, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in incidental Lewy body disease and Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(11):1260–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerkin RC, Adler CH, Hentz JG, Shill HA, Driver-Dunckley E, Mehta SH, et al. Improved diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease from a detailed olfactory phenotype. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4(10):714–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller A, Mungersdorf M, Reichmann H, Strehle G, Hummel T. Olfactory function in Parkinsonian syndromes. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9(5):521–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silveira-Moriyama L, Hughes G, Church A, Ayling H, Williams DR, Petrie A, et al. Hyposmia in progressive supranuclear palsy. Mov Disord. 2010;25(5):570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahlknecht P, Pechlaner R, Boesveldt S, Volc D, Pinter B, Reiter E, et al. Optimizing odor identification testing as quick and accurate diagnostic tool for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31(9):1408–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki M, Hashimoto M, Yoshioka M, Murakami M, Kawasaki K, Urashima M. The odor stick identification test for Japanese differentiates Parkinson’s disease from multiple system atrophy and progressive supra nuclear palsy. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenning GK, Shephard B, Hawkes C, Petruckevitch A, Lees A, Quinn N. Olfactory function in atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91(4):247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beach TG, Adler CH, Sue LI, Serrano G, Shill HA, Walker DG, et al. Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders and Brain and Body Donation Program. Neuropathology. 2015;35(4):354–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beach TG, Sue LI, Walker DG, Roher AE, Lue L, Vedders L, et al. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9(3):229–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32(3):489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauw JJ, Daniel SE, Dickson D, Horoupian DS, Jellinger K, Lantos PL, et al. Preliminary NINDS neuropathologic criteria for Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome (progressive supranuclear palsy). Neurology. 1994;44(11):2015–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dickson DW. Neuropathologic differentiation of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol. 1999;246 Suppl 2:II6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson DW, Rademakers R, Hutton ML. Progressive supranuclear palsy: pathology and genetics. Brain Pathol. 2007;17(1):74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beach TG, White CL 3rd, Hladik CL, Sabbagh MN, Connor DJ, Shill HA, et al. Olfactory bulb alpha-synucleinopathy has high specificity and sensitivity for Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117(2):169–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patin A, Pause BM. Human amygdala activations during nasal chemoreception. Neuropsychologia. 2015;78:171–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shill HA, Hentz JG, Caviness JN, Driver-Dunckley E, Jacobson S, Belden C, et al. Unawareness of Hyposmia in Elderly People With and Without Parkinson’s Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2016;3(1):43–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]