Abstract

Although available evidence indicates that Mexican-origin (MO) adults experience unique stressful life events, little is known about how stress may influence risk for developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) for this high-risk group. This study investigated the association between perceived stress and NAFLD and explored how this relationship varied by acculturation levels. In a cross-sectional study, a total of 307 MO adults from a community-based sample in the U.S-Mexico Southern Arizona border region completed self-reported measures of perceived stress and acculturation. NAFLD was identified as having a continuous attenuation parameter (CAP) score of ≥ 288 dB/m determined by FibroScan®. Logistic regression models were fitted to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for NAFLD. The prevalence of NAFLD was 50 % (n = 155). Overall, perceived stress was high (Mean = 15.9) for the total sample. There were no differences by NAFLD status (No NAFLD: Mean = 16.6; NAFLD: Mean = 15.3; p = 0.11). Neither perceived stress nor acculturation were associated with NAFLD status. However, the association between perceived stress and NAFLD was moderated by acculturation levels. Specifically with each point increase in perceived stress, the odds of having NAFLD were 5.5 % higher for MO adults with an Anglo orientation and 1.2 % higher for bicultural MO adults. In contrast, the odds of NAFLD for MO adults with a Mexican cultural orientation were 9.3 % lower with each point increase in perceived stress. In conclusion, results highlight the need for additional efforts to fully understand the pathways through which stress and acculturation may influence the prevalence of NAFLD in MO adults.

Keywords: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Liver disease, Acculturation, Perceived stress, Mexican-origin adults

1. Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), characterized by the accumulation of excess fat in the liver cells that is not caused by alcohol consumption, can result in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and progress to irreversible cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. (Alderete et al., 1999) While approximately 25 % of the U.S. population are affected by NAFLD each year, (Baik et al., 2019) Mexican-Origin (MO) adults are disproportionately impacted by NAFLD. When compared to Non-Hispanic Whites (30.6 %) and Non-Hispanic Blacks (21.4 %), MO adults have the highest prevalence of NAFLD (42.8 %). (Balakrishnan et al., 2017) Prior research emphasizes the importance of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors for driving NAFLD disparities, (Berry, 1992) but to the best of our knowledge no research to date has systematically examined the influence of perceived stress on NAFLD for MO adults, despite MO adults facing particularly stressful life experiences such as racial/ethnic discrimination, and acculturation.

Stress is a risk factor for a number of cardio-metabolic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, all of which are well-documented risk factors for the development of NAFLD. (Brown et al., 2020, Cabassa, 2003) Exposure to chronic stress can activate the hypothalamic–pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis and over stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in excessive release of neurotransmitters, hormones, and inflammatory cytokines, all of which could promote the development of NAFLD. (Cabassa, 2003) Further, as a way to cope with chronic stressors, individuals might engage in maladaptive behaviors and lifestyle choices (e.g., poor diet) that can negatively increase NAFLD risk. (Cano et al., 2014, Castañeda et al., 2015) Despite evidence suggesting an underlying association between stress and NAFLD, existent literature in the area is scarce. Results of the few existing studies in this area indicate an independent association between higher levels of perceived stress and a higher prevalence of NAFLD. (Caussy et al., 2018, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018) Yet, no studies to date have specifically focused on MO individuals.

Whether through acculturative challenges or migration-related life experiences, acculturation is a stressful experience for MO adults. Acculturation, the process of adjusting to and adopting a dominant culture, (Cervantes et al., 2016) has been associated with increased risk for hypertension, obesity, poor diet, and physical inactivity, which are all well-documented NAFLD risk factors. (Chalasani et al., 2018, Cigrovski Berkovic et al., 2021, Clark et al., 1999, Cohen and Syme, 1985, Cuellar et al., 1980, Cuellar et al., 1995, Festa et al., 2000, Finch et al., 2004, Garbarino and Magnavita, 2015) Despite acculturation conferring an increased risk for NAFLD, studies exploring the influence of acculturation and NAFLD in MO adults are limited, and those that exist have found no significant association between acculturation and NAFLD. (Berry, 1992, Cuellar et al., 1980) Of important note is that these studies relied on proxy measures of acculturation (i.e., place of birth, language preference, generational status, and length of residence in the U.S.), which have been criticized by their inability to capture the psychological, behavioral, and attitudinal changes that occur during the acculturation process. (Garcia et al., 2017) Thus, building upon existent research, this study sought to quantify the contribution of perceived stress on NAFLD status in MO adults. In addition, as stress exposure might not manifest uniformly across groups, (Hamer et al., 2008) we explored how the association between perceived stress and NAFLD varied by level of acculturation (i.e., Anglo, Bicultural, and Mexican Orientation).

2. Methods

2.1. Study sample

Participants included 307 MO adults residing in Southern Arizona. Eligible participants: 1) were between the ages of 18–64 years, 2) had a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m (Baik et al., 2019), 3) were able to provide informed consent, and 4) had the ability to speak, read, and write in English/Spanish. Individuals were not eligible to participate if they reported ongoing or recent alcohol consumption (≥21 standard drinks on average per week for men and ≥ 14 standard drinks on average per week for women); had a history of exposure to hepatotoxic drugs; were previously diagnosed with liver disease or liver cancer; had an active chronic gastrointestinal disorder (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease); were taking any medication or supplement known to affect body composition; had uncontrolled vascular or metabolic disease (e.g., high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes); had any syndrome or disease known to affect body composition or fat distribution; participated in any structured exercise, nutrition, or weight-loss program within 6 months of recruitment; previously had bariatric surgery; or were currently pregnant or breastfeeding. (Han, 2020).

2.2. Participant recruitment and study procedures

Details regarding study procedures have been published elsewhere. (Hovey, 2000) Briefly, participants were recruited from community-based settings in the Tucson area. Data collection and study procedures took place at Arizona Liver Health in Tucson, AZ. Prior to beginning data collection, informed consent was obtained. Participants completed a 60–90 min in-person visit in which anthropometric measures, NAFLD status, and self-reported questionnaires were obtained. Study visits and self-reported questionnaires were completed in the participants’ preferred language (Spanish or English). All participants received a written summary of their anthropometric assessment, NAFLD status, and a list of available local resources should they choose to seek medical care. After completing all data collection procedures, participants were thanked and compensated US $25 for their time. Recruitment and data collection occurred concurrently during May 2019 and March 2020. The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board (IRB #1902380787) approved all study materials and research protocol.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Non-Alcoholic Fatty liver disease

NAFLD status was identified via vibration-controlled transient elastography (FibroScan® 430 MINI + ). The FibroScan®, a 10 to 15 min procedure, is a non-invasive technique that simultaneously derives the median for continuous attenuation parameter (CAP) and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) values. (Hussain et al., 2021) CAP values range from 100 to 400 dB/m, with higher values indicated higher amounts of liver fat. LSM values range from 1.5 to 75 kPa, with higher values indicating more advanced fibrosis. (Institute and Inc, 2015) For the purposes of the study, NAFLD status was identified as having a continuous attenuation parameter (CAP) score of ≥ 288 dB/m using FibroScan®. (Kallwitz et al., Mar 2015) Scans were considered complete and valid if participants fasted for at least 3 h, more than 10 LSM measures were obtained, and the liver stiffness IQR/median value was<30 %. (Hussain et al., 2021).

2.3.2. Perceived stress

Levels of perceived stress were measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), a valid and reliable measure in Hispanic populations. (Kamody et al., 2021) The four positively worded items (Items 4, 5, 7, 8) were reversed scored and a total score was computed by adding all 10-items ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived stress.

2.3.3. Acculturation

Participants’ acculturation was assessed with the revised Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans II (ARSMA-II). (Kang et al., 2020) Responses were averaged to obtain both an Anglo orientation (AOS) and a Mexican orientation score (MOS). To obtain a linear acculturation score, the MOS mean was subtracted from the AOS mean. The linear acculturation score was classified into three different categories to reflect participants’ acculturation levels: (1) Anglo-oriented (≥1.19); (2) Bicultural (≥ − 1.33 and < 1.19); and (3) Mexican-oriented (<-1.33).

2.3.4. Anthropometric measures

Participants’ height, weight, and waist circumference were collected using standardized methods. (Lambrechts, 2020) Using a wall-mounted stadiometer (ShorrBoard) participants’ height was measured without shoes, twice to the nearest 0.1 cm. In cases where the height measurements differed by more than 0.5 cm, a third measurement was taken. Without shoes and in participants’ street clothes, participants’ weight was measured twice on a calibrated digital scale (Seca 8760 to the nearest 0.1 kg. A third measurement was taken if the two measurements diverged by more than 0.2 kg. The average of the two measurements meeting the criteria for height and weight were used to calculate body mass index (BMI). BMI was computed by dividing the body weight in kilograms by squared height in meters (kg/m2).

2.3.5. Demographic characteristics and Self-reported health status

Descriptive variables including age, sex, self-reported health status (e.g., history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or high cholesterol), marital status, employment status, annual household income, highest level of education completed, health insurance status, and primary language spoken at home were included as covariates in the analyses of the current study.

2.4. Statistical analyses

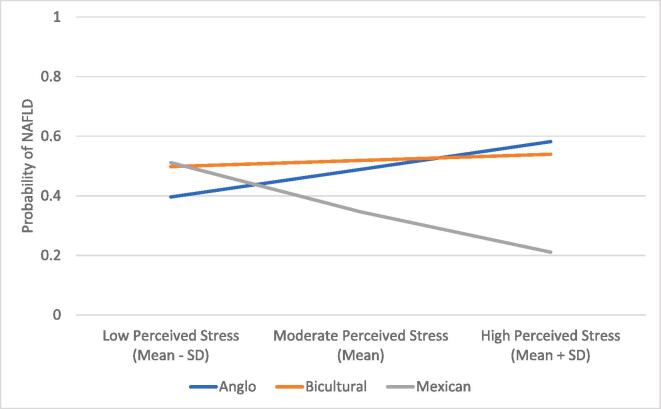

Data analysis was conducted using SAS software. (Lara et al., 2005) Summary statistics were used to describe the sample stratified by NAFLD status. Chi-square tests were performed to explore the distribution of NAFLD risk factors by acculturation level. Bivariate analyses to explore the unadjusted relationship between each of the variables of interest and NAFLD status were conducted. Two multivariate logistic regression models were fit to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for NAFLD status. Model 1 tested the relationship between NAFLD status, perceived stress, and acculturation while controlling for the influence of demographic and health variables. Model 2 regressed NAFLD status on the variables included in model 1 with the addition of an interaction term (perceived stress × acculturation). To better understand statistically significant interactions, simple odds of NAFLD status were computed for each combination of perceived stress and level of acculturation. Predicted probabilities at three different levels of perceived stress (mean ± SD) were obtained and graphed to depict the effect of perceived stress on NAFLD at each level of acculturation. All models were fitted in SAS using PROC LOGISTIC.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

Of the total sample, 155 participants were identified as having NAFLD (50.5 %). Most participants were classified as obese; however, the percentage was higher among those with NAFLD than their peers (59.6 % vs 40.4 %, p < 0.0001). While only 81 participants reported a prior history of high cholesterol, the proportion of participants with high cholesterol was higher among those with NAFLD than their counterparts (61.7 % vs 38.3 %, p = 0.02). No statistically significant differences were observed for perceived stress, acculturation, hypertension, diabetes, and history of emotional/psychiatric problems. All other participant characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Status.

|

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Status |

p-value * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No NAFLD (n = 152) |

NAFLD (n = 155) |

||||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.11 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.6 (6.5) | 15.3 (7.4) | |||||

| Acculturation | |||||||

| Mexican Oriented | 78 | (51.7%) | 73 | (48.3%) | 0.68 | ||

| Bicultural | 63 | (46.7 %) | 72 | (53.3 %) | |||

| Anglo Oriented | 11 | (52.4 %) | 10 | (47.6 %) | |||

| High Blood Pressure | 0.63 | ||||||

| Yes | 29 | (46.8 %) | 33 | (53.2 %) | |||

| No | 123 | (50.2 %) | 122 | (49.8 %) | |||

| High Cholesterol | 0.02 | ||||||

| Yes | 31 | (38.3 %) | 50 | (61.7 %) | |||

| No | 121 | (53.5 %) | 105 | (46.5 %) | |||

| Diabetes | 0.20 | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | (38.7 %) | 19 | (61.3 %) | |||

| No | 140 | (50.7 %) | 136 | (49.3 %) | |||

| Emotional/Psychiatric Problems | 0.14 | ||||||

| Yes | 9 | (69.2 %) | 4 | (30.8 %) | |||

| No | 142 | (48.5 %) | 151 | (51.5 %) | |||

| Weight Category | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Overweight | 72 | (66.1 %) | 37 | (33.9 %) | |||

| Obese | 80 | (40.4 %) | 118 | (59.6 %) | |||

| Sex | 0.47 | ||||||

| Male | 59 | (52.2 %) | 54 | (47.8 %) | |||

| Female | 93 | (47.9 %) | 101 | (52.1 %) | |||

| Age | 0.56 | ||||||

| < 29 years | 20 | (62.5 %) | 12 | (37.5 %) | |||

| 30–39 years | 35 | (48.6 %) | 37 | (51.4 %) | |||

| 40–49 years | 41 | (45.1 %) | 50 | (54.9 %) | |||

| 50–59 years | 42 | (50.6 %) | 41 | (49.4 %) | |||

| greater than 60 years | 14 | (48.3 %) | 15 | (51.7 %) | |||

| Language Spoken at Home | 0.62 | ||||||

| English | 42 | (51.9 %) | 39 | (48.1 %) | |||

| Spanish | 110 | (48.7 %) | 116 | (51.3 %) | |||

| Educational Level | 0.07 | ||||||

| Grades 1–8 | 25 | (56.8 %) | 19 | (43.2 %) | |||

| Attended Some High school | 15 | (32.6 %) | 31 | (67.4 %) | |||

| Graduated High school/GED | 32 | (47.8 %) | 35 | (52.2 %) | |||

| Some College | 31 | (52.5 %) | 28 | (47.5 %) | |||

| Bachelors | 25 | (64.1 %) | 14 | (35.9 %) | |||

| Graduate Degree or Higher | 23 | (45.1 %) | 28 | (54.9 %) | |||

| Employed | 0.08 | ||||||

| Yes | 115 | (52.7 %) | 103 | (47.3 %) | |||

| No | 37 | (41.6 %) | 52 | (58.4 %) | |||

| Annual Household Income | 0.89 | ||||||

| < $29,999 | 79 | (48.4 %) | 81 | (51.6 %) | |||

| $30,000 – $59,000 | 54 | (51.4 %) | 51 | (48.6 %) | |||

| > $60,000 | 22 | (48.9 %) | 23 | (51.1 %) | |||

| Married/living with Partner | 0.32 | ||||||

| Yes | 106 | (47.7 %) | 116 | (52.3 %) | |||

| No | 416 | (54.1 %) | 39 | (45.9 %) | |||

| Health Insurance Status | 0.43 | ||||||

| Yes | 94 | (51.4 %) | 89 | (48.6 %) | |||

| No | 58 | (46.8 %) | 66 | (53.2 %) | |||

Note: Values displayed are means (SD) for continuous variables and counts (%) for categorical variables unless otherwise noted.

*T-test (continuous) and chi-squared test (categorical).

Table 2 presents the distribution of several known NAFLD risk factors by level of acculturation.

Table 2.

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Risk Factors in Mexican-origin Adults by Level of Acculturation.

|

Acculturation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mexican Oriented (n = 151) |

Bicultural (n = 135) |

Anglo Oriented (n = 21) |

p-value * | |||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.61 | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.3 (6.29) | 15.8 (7.24) | 14.8 (10.04) | |||||

| High Blood Pressure | 0.03 | |||||||

| Yes | 38 | (61.3 %) | 18 | (29.0 %) | 6 | (9.7 %) | ||

| No | 113 | (46.1 %) | 117 | (47.8 %) | 15 | (6.1 %) | ||

| High Cholesterol | <0.01 | |||||||

| Yes | 52 | (64.2 %) | 26 | (32.1 %) | 3 | (3.7 %) | ||

| No | 99 | (43.8 %) | 109 | (48.2 %) | 18 | (8.0 %) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.10 | |||||||

| Yes | 20 | (64.5 %) | 8 | (25.8 %) | 3 | (9.7 %) | ||

| No | 131 | (47.8 %) | 127 | (46.0 %) | 18 | (6.5 %) | ||

| Emotional/Psychiatric Problems | 0.92 | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | (53.8 %) | 5 | (38.5 %) | 1 | (7.7 %) | ||

| No | 144 | (49.1 %) | 129 | (44.0 %) | 20 | (6.8 %) | ||

| Weight Category | 0.02 | |||||||

| Overweight | 65 | (59.6 %) | 38 | (34.9 %) | 6 | (5.5 %) | ||

| Obese | 86 | (43.4 %) | 97 | (49.0 %) | 15 | (7.6 %) | ||

*Chi-squared test (categorical).

Mexican oriented participants were more likely to be overweight (59.6 %) than bicultural (34.9 %) and Anglo oriented individuals (5.5 %, p = 0.02). Similarly, the proportion of participants with a self-reported high blood pressure (61.3 %) was higher among Mexican oriented participants than bicultural (29.0 %) and Anglo oriented individuals (9.7 %, p = 0.03). High cholesterol was higher among participants with a Mexican orientation (64.2 %) compared to bicultural (32.1 %) and Anglo oriented participants (3.7 %, p < 0.01). No statistically significant differences were observed for perceived stress, diabetes, and emotional/psychiatric problems.

Table 3 presents unadjusted, adjusted, and moderation logistic regression models of the association between perceived stress and NAFLD status. Neither perceived stress (OR = 0.97, 95 % CI = 0.94, 1.01) nor acculturation levels (bicultural OR = 1.26, 95 % CI = 0.50, 3.16; Mexican oriented OR = 1.03, 95 % CI = 0.41, 2.57) were associated with NAFLD status. When the model accounted for health status variables and demographic characteristics (Model 2), the relationship between perceived stress (OR = 0.98, 95 % CI = 0.94, 1.01), acculturation levels (bicultural OR = 1.32, 95 % CI = 0.44, 3.97; Mexican oriented OR = 0.67, 95 % CI = 0.53, 2.07), and NAFLD remained statistically insignificant. However, self-reported history of high cholesterol (OR = 3.07, 95 % CI = 1.54, 6.04), and obesity status (OR = 4.19, 95 % CI = 2.32, 7.53) were associated with increased odds of having NAFLD. Self-reported high blood pressure, diabetes, emotional/psychiatric problems, sex, age, language spoken at home, educational level, annual household income, marital status, and health insurance were not associated with NAFLD.

Table 3.

Unadjusted, Adjusted, and Multivariate Logistic Moderation Models.

|

Unadjusted Bivariate Logistic Regressions |

Adjusted Multivariate Logistic Regression |

Multivariate Logistic Moderation Model |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | p-value* | OR | 95 % CI | p-value† | OR | 95 % CI | p-value§ | ||||

| Perceived Stress | 0.97 | 0.94-1.01 | 0.11 | 0.98 | 0.94-1.01 | 0.22 | 1.06 | 0.95-1.17 | 0.31 | |||

| Acculturation | ||||||||||||

| Anglo Oriented | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | |||

| Bicultural | 1.26 | 0.50–3.16 | 0.63 | 1.32 | 0.44–3.97 | 0.62 | 2.19 | 0.29–16.75 | 0.45 | |||

| Mexican Oriented | 1.03 | 0.41–2.57 | 0.95 | 0.67 | 0.19–2.42 | 0.54 | 6.15 | 0.69–55.01 | 0.10 | |||

| High Blood Pressure | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 1.05 | 0.53–2.07 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.49–1.94 | 0.95 | ||||||

| High Cholesterol | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 3.23 | 1.63–6.40 | <0.001 | 3.78 | 1.86–7.68 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 1.67 | 0.64–4.33 | 0.29 | 1.44 | 0.54–3.81 | 0.47 | ||||||

| Emotional/Psychiatric Problems | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 0.26 | 0.64–1.07 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.07–1.16 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Weight Category | ||||||||||||

| Overweight | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Obese | 3.89 | 2.17–6.99 | <0.001 | 4.19 | 2.30–7.63 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Female | 0.96 | 0.54–1.72 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.56–1.82 | 0.99 | ||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| < 29 years | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| 30–39 years | 1.80 | 0.66–4.93 | 0.25 | 1.83 | 0.66–5.07 | 0.25 | ||||||

| 40–49 years | 1.83 | 0.66–5.08 | 0.24 | 1.70 | 0.61–4.78 | 0.31 | ||||||

| 50–59 years | 1.55 | 0.55–4.32 | 0.40 | 1.54 | 0.54–4.36 | 0.42 | ||||||

| greater than 60 years | 1.31 | 0.38–4.47 | 0.67 | 1.26 | 0.36–4.37 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Language Spoken at Home | ||||||||||||

| English | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Spanish | 1.36 | 0.63–2.91 | 0.43 | 1.45 | 0.67–3.12 | 0.34 | ||||||

| Educational Level | ||||||||||||

| Grades 1–8 | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Attended Some High school | 2.15 | 0.80–5.78 | 0.13 | 1.75 | 0.63–4.84 | 0.28 | ||||||

| Graduated High school/GED | 1.03 | 0.42–2.52 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 0.31–2.06 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Some College | 1.14 | 0.42–3.07 | 0.80 | 0.98 | 0.35–2.73 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Bachelors | 0.86 | 0.29–2.60 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.25–2.38 | 0.64 | ||||||

| Graduate Degree or Higher | 1.79 | 0.66–4.82 | 0.25 | 1.61 | 0.58–4.46 | 0.36 | ||||||

| Employed | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 0.67 | 0.35–1.31 | 0.24 | 0.66 | 0.33–1.31 | 0.23 | ||||||

| Annual Household Income | ||||||||||||

| < $29,999 | Ref | – | – | |||||||||

| $30,000 – $59,000 | 1.11 | 0.57–2.17 | 0.75 | 1.09 | 0.55–2.14 | 0.81 | ||||||

| > $60,000 | 1.22 | 0.48–3.09 | 0.67 | 1.31 | 0.51–3.36 | 0.58 | ||||||

| Married/living with Partner | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.52–1.88 | 0.97 | 1.03 | 0.53–1.98 | 0.93 | ||||||

| Health Insurance Status | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 0.74 | 0.39–1.38 | 0.34 | 0.74 | 0.39–1.41 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Interaction | ||||||||||||

| Perceived Stress × Acculturation | ||||||||||||

| Anglo Oriented | Ref | – | – | |||||||||

| Bicultural | 0.96 | 0.86–1.08 | 0.48 | |||||||||

| Very Mexican Oriented | 0.86 | 0.76–0.97 | 0.01 | |||||||||

Note: Weight categories were derived based on BMI. Participants with a BMI ≤ 30 were classified as overweight, whereas participants with a BMI ≥ 30 were classified as obese.

*Bivariate logistic regressions.

† Model tested the relationship between NAFLD status, perceived stress, and acculturation while adjusting for the influence of demographic and health variables.

§ Model regressed included variables from multivariate logistic regression with the addition of the interaction term between perceived stress*acculturation. Model adjusted for the effect of demographic and health variables.

Examining the interaction effect (Model 3), the association between perceived stress and NAFLD status was moderated by acculturation levels (Fig. 1). With each point increase in perceived stress, the odds of having NAFLD were 5.5 % higher for MO adults with an Anglo orientation (OR = 1.05, 95 % CI = 0.95, 1.17) and 1.18 % higher for bicultural MO adults (OR = 1.01, 95 % CI = 0.96, 1.07). In contrast, the odds of NAFLD for MO adults with a very Mexican cultural orientation were 9.3 % lower with each point increase in perceived stress (OR = 0.91, 95 % CI = 0.85, 0.97).

Fig. 1.

Mexican-origin adults’ Predicted Probability of having Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease for each Combination of Perceived Stress and Level of Acculturation.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to delineate the roles of perceived stress, and acculturation in NAFLD in a community-based sample of MO adults in Southern Arizona. While half of the sample was identified as having NAFLD, perceived stress that was assessed with the PSS-10 was not predictive of NAFLD. In addition, despite the higher prevalence of NAFLD risk factors among Mexican-oriented individuals (i.e., high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and being overweight), levels of acculturation were not associated with NAFLD. When interaction effects were explored, the effect of perceived stress on NAFLD was modified by levels of acculturation. Specifically, with each point increase in perceived stress, the odds of NAFLD were lower for MO adults with a very Mexican cultural orientation compared to bicultural and Anglo-oriented individuals. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association between perceived stress, levels of acculturation, and NAFLD in MO adults. Thus, additional efforts are warranted to determine the underlying mechanisms through which perceived stress and acculturation may impact Mexican-origin adults’ risk for NAFLD.

Though perceived stress has been previously associated with NAFLD status, (Caussy et al., 2018, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018) in the current study, perceived stress was not directly associated with NAFLD. This is surprising, given that perceived stress has previously been linked to increased adiposity, (Lee et al., 2017) higher risk of cardiovascular disease, (Liu et al., 2009) and metabolic syndrome, (Lohman et al., 1988) well-recognized risk factors for NAFLD. While overall, perceived stress was high in the study sample (M = 15.9), post-hoc analyses indicated that perceived stress was not associated with self-reported history of hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes, or obesity. This suggests some stressors, although prevalent, may not impact MO adults’ health in the expected direction. MO adults are particularly vulnerable to unique stressors associated with the acculturation process. (Mainous et al., 2006) Acculturative stress, the stress that directly results from the acculturation process, (Morrill et al., 2021) has been linked to poor health outcomes that may increase MO adults risk for NAFLD. (Neuhouser et al., 2004, Oeda et al., 2020, Riolo et al., 2005, Ruiz et al., 2018, Ruiz et al., 2016) Yet, acculturative stress has been rarely considered in the context of NAFLD. Further, as it has been reported that some individuals, as a coping response to stress, may not report perceiving any stress but still experience physiological responses to the stressor, (Sabogal et al., 1987, Schneiderman et al., 2005) additional efforts using objective measures of stress (e.g., allostatic load) are warranted.

In contrast to previous work indicating a negative effect of acculturation on health, (Chalasani et al., 2018, Cigrovski Berkovic et al., 2021, Clark et al., 1999, Cohen and Syme, 1985, Cuellar et al., 1980, Cuellar et al., 1995, Festa et al., 2000) in the current study, MO adults with a Mexican cultural orientation (lower acculturation) were more likely to have high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and be overweight. Nevertheless, acculturation was not associated with NAFLD status. The discordant findings of greater prevalence of risk factors for NAFLD among the less acculturated, but lack of an association between acculturation and NAFLD, may be attributed to the utilization of varying acculturation measures. In fact, it has been found that depending on the measure of acculturation, the effect of acculturation in health may be negative, positive, or non-existent. (Festa et al., 2000) For instance, it has been found that type 2 diabetes is more prevalent in Spanish-speaking individuals; (Shaheen et al., Dec 2021) however, birthplace is not a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. (Shea et al., 2021) Furthermore, while one of the strengths of the current study is the use of the multidimensional ARSMA-II scale, this measure only captures behavioral aspects of acculturation (e.g., watching English/Spanish television). (Kang et al., 2020) Thus, as research on the influence of acculturation in NAFLD is in its early stages, further research on the interactions between different components of acculturation (e.g., familism) and NAFLD risk factors will help elucidate the role of acculturation in NAFLD among MO adults.

Nevertheless, acculturation moderated the relationship between perceived stress and NAFLD status. While there was a beneficial effect of perceived stress for MO adults with a very Mexican cultural orientation, this was not the case for MO adults with an Anglo or bicultural orientation. High Mexican cultural orientation (low acculturation) is associated with robust social support, (Simón et al., 2014) perhaps the strongest sociocultural factor shown to buffer the negative effects of stress on health. (Szabó, 2022) However, as individuals become more acculturated, MO adults’ network size and cohesion might be negatively impacted. In fact, it has been documented that endorsement of traditional cultural values such as familism decrease as acculturation increases. (Unger et al., 2004) This is of particular note, as it is hypothesized that traditional cultural values moderate MO adults’ social network size and cohesion. (Ward and Szabó, 2019) Although the study’s findings appear perplexing, they are in line with the Hispanic sociocultural health resilience model that suggests that cultural processes (e.g., traditional cultural values) influence engagement of social networks with higher network resources then leading to health benefits. (Wardle et al., 2011) Taken together, this work suggests that the beneficial effect of perceived stress on NAFLD for MO adults with a very Mexican cultural orientation is a function of a higher number of social resources available to this particular group. Nonetheless, it remains to be determined how social support influences MO adults’ risk for NAFLD across the acculturation spectrum.

Though this study points to the importance of perceived stress and acculturation on MO adults' risk for NAFLD, several limitations should be noted when interpreting the results. First, perceived stress data is based on self-report instead of objective measures of stress. While the use of the PSS-10 to measure MO adults’ perceived stress levels minimized the possibility of reporting bias, the scale might fail to capture unique stressors experienced by MO adults. Thus, future research should incorporate culturally informed stress assessments such as the Hispanic Stress Inventory-2 (Younossi et al., 2016) to capture an accurate representation of the stressors experienced by MO adults. Second, representation of normal-weight individuals was lacking in the current study's sample. This is of note, as it has been demonstrated that NAFLD also develops in individuals with a normal BMI (lean NAFLD). Third, analyses were compelled to assess NAFLD risk factors based on participants’ self-reports of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes, which limit the ability to make inferences regarding actual biological outcomes. Fourth, while lifestyle modification is the gold standard treatment for individuals with NAFLD(Zelber-Sagi et al., 2011), analyses failed to adjust for the influence of physical activity and dietary behaviors on NAFLD risk. Lastly, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to determine a causal relationship between perceived stress, acculturation and NAFLD. Yet, despite these limitations, study findings are still informative as they shed light on the role of perceived stress and acculturation on NAFLD in MO adults, a high-risk and underrepresented subpopulation in the NAFLD literature.

In conclusion, this study is an initial effort to characterize the impact of psychosocial factors on MO adults with NAFLD. The results of this study have significant implications for public health interventions. Specifically, they shed light to the need for cancer-risk reduction interventions to incorporate stress-management strategies to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with hepatocellular carcinoma, particularly when working with MO adults with an Anglo or bicultural cultural orientation. However, future research is necessary to fully understand the pathways through which stress and acculturation influence the prevalence of NAFLD in MO adults.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (Institutional Cancer Research Grant No IRG-16-124-37 to D.G.), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (award number K01MD014761 to D.G.), University of Arizona Health Sciences Center for Health Disparities Research, and University of Arizona Core Facilities Pilot Program to (D.G.). This research used the University of Arizona Cancer Center Behavioral Measurement and Interventions Shared Resource (P30 CA023074).

6. Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the genetic information collected as part of the study.

7. Institutional review board statement

The University of Arizona Institutional Review Board (IRB #1902380787) approved all study materials and research protocol.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

A. Maldonado: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. E.A. Villavicencio: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. R.M. Vogel: . Pace: . J. Ruiz: Writing – review & editing. N. Alkhouri: . Garcia: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all study participants, the Nosotros staff, the Tucson Tanque Verde Swap Meet, the Mexican Consulate, and the University of Arizona Collaboratory for Metabolic Disease Prevention and Treatment. In addition, the University of Arizona Health Sciences Center for Border Health Disparities provided staff support, and Arizona Liver Health provided clinical space and conducted all FibroScans.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Alderete E., Vega W.A., Kolody B., Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Depressive symptomatology: Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors among Mexican migrant farmworkers in California. J. Community Psychol. 1999;27(4):457–471. [Google Scholar]

- Baik S.H., Fox R.S., Mills S.D., et al. Reliability and validity of the Perceived Stress Scale-10 in Hispanic Americans with English or Spanish language preference. J. Health Psychol. 2019;24(5):628–639. doi: 10.1177/1359105316684938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan M., Kanwal F., El-Serag H.B., Thrift A.P. Acculturation and NAFLD Risk among Hispanics of Mexican-Origin: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Associat. 2017;15(2):310. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.09.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J.W. Acculturation and adaptation in a new society. Int. Migr. 1992;30 [Google Scholar]

- Brown L.L., Mitchell U.A., Ailshire J.A. Disentangling the stress process: Race/ethnic differences in the exposure and appraisal of chronic stressors among older adults. J. Gerontol.: Series B. 2020;75(3):650–660. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa L.J. Measuring acculturation: Where we are and where we need to go. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2003;25(2):127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Cano M.Á., Castillo L.G., Castro Y., de Dios M.A., Roncancio A.M. Acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among Mexican and Mexican American students in the US: Examining associations with cultural incongruity and intragroup marginalization. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2014;36(2):136–149. doi: 10.1007/s10447-013-9196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H., Holmes S.M., Madrigal D.S., Young M.-E.-D., Beyeler N., Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2015;36:375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caussy C., Alquiraish M.H., Nguyen P., et al. Optimal threshold of controlled attenuation parameter with MRI-PDFF as the gold standard for the detection of hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2018;67(4):1348–1359. doi: 10.1002/hep.29639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Liver Ultrasound Transient Elastography Procedures Manual 2018. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2017-2018/manuals/2018_Liver_Ultrasound_Elastography_Procedures_Manual.pdf.

- Cervantes R.C., Fisher D.G., Padilla A.M., Napper L.E. The Hispanic Stress Inventory Version 2: Improving the assessment of acculturation stress. Psychol. Assess. 2016;28(5):509. doi: 10.1037/pas0000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani N., Younossi Z., Lavine J.E., et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328–357. doi: 10.1002/hep.29367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigrovski Berkovic M., Bilic-Curcic I., Mrzljak A., Cigrovski V. NAFLD and Physical Exercise: Ready, Steady, Go! Front. Nutr. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.734859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R., Anderson N.B., Clark V.R., Williams D.R. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. Am. Psychol. 1999;54(10):805. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S.E., Syme S. Academic Press; 1985. Social support and health. [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I., Harris L.C., Jasso R. An acculturation scale for Mexican American normal and clinical populations. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1980 [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar I., Arnold B., Gonzalez G. Cognitive referents of acculturation: Assessment of cultural constructs in Mexican Americans. J. Community Psychol. 1995;23(4):339–356. [Google Scholar]

- Festa A., D’Agostino R., Jr, Howard G., Mykkanen L., Tracy R.P., Haffner S.M. Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Circulation. 2000;102(1):42–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch B.K., Frank R., Vega W.A. Acculturation and Acculturation Stress: A Social-Epidemiological Approach to Mexican Migrant Farmworkers' Health 1. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004;38(1):236–262. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino S., Magnavita N. Work stress and metabolic syndrome in police officers. A prospective study. PloS one. 2015;10(12):e0144318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia A.F., Wilborn K., Mangold D.L. The Cortisol Awakening Response Mediates the Relationship Between Acculturative Stress and Self-Reported Health in Mexican Americans. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017;51(6):787–798. doi: 10.1007/s12160-017-9901-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M., Molloy G.J., Stamatakis E. Psychological distress as a risk factor for cardiovascular events: pathophysiological and behavioral mechanisms. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;52(25):2156–2162. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han A.L. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dietary habits, stress, and health-related quality of life in Korean adults. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1555. doi: 10.3390/nu12061555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey J.D. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation in Mexican immigrants. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2000;6(2):134. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M., Howell J.L., Peek M.K., Stowe R.P., Zawadzki M.J. Psychosocial stressors predict lower cardiovascular disease risk among Mexican-American adults living in a high-risk community: Findings from the Texas City Stress and Health Study. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0257940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 14.1 User’s Guide. SAS Institute Inc.; 2015.

- Kallwitz E.R., Daviglus M.L., Allison M.A., et al. Prevalence of suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Hispanic/Latino individuals differs by heritage. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Associat. Mar 2015;13(3):569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamody R.C., Grilo C.M., Vásquez E., Udo T. Diabetes prevalence among diverse Hispanic populations: considering nativity, ethnic discrimination, acculturation, and BMI. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia. Bulimia Obesity. 2021;26(8):2673–2682. doi: 10.1007/s40519-021-01138-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang D, Zhao D, Ryu S, et al. Perceived stress and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in apparently healthy men and women. Scientific Reports. 2020/01/08 2020;10(1):38. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-57036-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lambrechts A.A. The super-disadvantaged in higher education: Barriers to access for refugee background students in England. High. Educ. 2020;80(5):803–822. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M., Gamboa C., Kahramanian M.I., Morales L.S., Bautista D.E. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Kim Y., Friso S., Choi S.-W. Epigenetics in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2017;54:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Probst J.C., Harun N., Bennett K.J., Torres M.E. Acculturation, physical activity, and obesity among Hispanic adolescents. Ethn. Health. 2009;14(5):509–525. doi: 10.1080/13557850902890209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman T.G., Roche A.F., Martorell R. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Human kinetics books. 1988 [Google Scholar]

- Mainous A.G., III, Majeed A., Koopman R.J., et al. Acculturation and diabetes among Hispanics: evidence from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(1):60–66. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill KE, Bland VL, Klimentidis YC, Hingle MD, Thomson CA, Garcia DO. Assessing Interactions between PNPLA3 and Dietary Intake on Liver Steatosis in Mexican-Origin Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Jul 1 2021;18(13)doi:10.3390/ijerph18137055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Neuhouser M.L., Thompson B., Coronado G.D., Solomon C.C. Higher fat intake and lower fruit and vegetables intakes are associated with greater acculturation among Mexicans living in Washington State. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004;104(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeda S., Tanaka K., Oshima A., Matsumoto Y., Sueoka E., Takahashi H. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and factors affecting measurements. Diagnostics. 2020;10(11):940. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10110940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riolo S.A., Nguyen T.A., Greden J.F., King C.A. Prevalence of depression by race/ethnicity: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Am. J. Public Health. 2005;95(6):998–1000. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J.M., Hamann H.A., Mehl M.R., O’Connor M.-F. The Hispanic health paradox: From epidemiological phenomenon to contribution opportunities for psychological science. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016;19(4):462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J.M., Sbarra D., Steffen P.R. Hispanic ethnicity, stress psychophysiology and paradoxical health outcomes: A review with conceptual considerations and a call for research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2018;131:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F., Marín G., Otero-Sabogal R., Marín B.V., Perez-Stable E.J. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn't? Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1987;9(4):397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman N., Ironson G., Siegel S.D. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2005;1:607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen M., Pan D., Schrode K.M., et al. Reassessment of the Hispanic Disparity: Hepatic Steatosis Is More Prevalent in Mexican Americans Than Other Hispanics. Hepatol Commun. Dec 2021;5(12):2068–2079. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S., Lionis C., Kite C., et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and potential links to depression, anxiety, and chronic stress. Biomedicines. 2021;9(11):1697. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9111697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simón H., Ramos R., Sanromá E. Immigrant occupational mobility: Longitudinal evidence from Spain. Eur. J. Popul. 2014;30(2):223–255. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó Á. Addressing the causes of the causes: Why we need to integrate social determinants into acculturation theory. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- Unger J.B., Reynolds K., Shakib S., Spruijt-Metz D., Sun P., Johnson C.A. Acculturation, physical activity, and fast-food consumption among Asian-American and Hispanic adolescents. J. Community Health. 2004;29(6):467–481. doi: 10.1007/s10900-004-3395-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Szabó Á. Affect, behavior, cognition, and development: Adding to the alphabet of acculturation. The handbook of culture and psychology. Oxford University Press; 2019.

- Wardle J., Chida Y., Gibson E.L., Whitaker K.L., Steptoe A. Stress and adiposity: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obesity. 2011;19(4):771–778. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi Z.M., Koenig A.B., Abdelatif D., Fazel Y., Henry L., Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelber-Sagi S., Ratziu V., Oren R. Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: an overview of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2011;17(29):3377. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i29.3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the genetic information collected as part of the study.

Data will be made available on request.