Abstract

l-Sorbose, an excellent cellulase and xylanase inducer from Trichoderma reesei PC-3-7, also induced α-l-arabinofuranosidase (α-AF) activity. An α-AF induced by l-sorbose was purified to homogeneity, and its molecular mass was revealed to be 35 kDa (AF35), which was not consistent with that of the previously reported α-AF. Another species, with a molecular mass of 53 kDa (AF53), which is identical to that of the reported α-AF, was obtained by a different purification procedure. Acid treatment of the ammonium sulfate-precipitated fraction at pH 3.0 in the purification steps or pepsin treatment of the purified AF53 reduced the molecular mass to 35 kDa. Both purified enzymes have the same enzymological properties, such as pH and temperature effects on activity and kinetic parameters for p-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (pNPA). Moreover, the N-terminal amino acid sequences of these enzymes were identical with that of the reported α-AF. Therefore, it is obvious that AF35 results from the proteolytic cleavage of the C-terminal region of AF53. Although AF35 and AF53 showed the same catalytic constant with pNPA, the former showed drastically reduced specific activity against oat spelt xylan compared to the latter. Furthermore, AF53 was bound to xylan rather than to crystalline cellulose (Avicel), but AF35 could not be bound to any of the glycans. These results suggest that AF53 is a modular glycanase, which consists of an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal noncatalytic xylan-binding domain.

Xylan is the most abundant renewable biomass polymer next to cellulose and one of the major components of plant cell walls. Xylan refers to any of a class of heterogeneous plant polysaccharides whose compositions differ depending on their origins. It consists of a backbone of β-1,4-linked xylopyranose and side chains of α-l-arabinofuranoside, an acetyl group, and/or 4-o-methylglucuronic acid at the C-2 and C-3 positions of the xylose units. Xylan-degrading enzyme systems of microorganisms include endo-β-1,4-xylanase (EC 3.2.1.8), β-d-xylosidase (EC 3.2.1.37), and the side chain-debranching enzymes α-l-arabinofuranosidase (EC 3.2.1.55) (α-AF), α-glucuronidase (EC 3.2.1.139), and acetylxylan esterase (EC 3.1.1.72) (20). In addition to xylanase, these side chain-cleaving activities were required for effective degradation of this polysaccharide because the side chains hinder xylanase from accessing the xylan backbone (20).

Plant cell wall hydrolases often contain both catalytic and noncatalytic domains linked by a hinge region. Most cellulose-binding domains (CBDs) are quite common not only in cellulases but also in hemicellulases (24). The role of the CBDs located in hemicellulases is unclear, although it is thought that they bring the hemicellulase into contact with the plant cell wall. Recently, xylan-binding domains (XBDs) were reported to be present in enzymes isolated from Cellulomonas fimi, Thermomonospora fusca, and Streptomyces lividans (2, 7, 8, 23). The amino acid sequences of these XBDs show some similarities to those of bacterial CBDs.

An α-AF can release terminal α-l-1,2- and α-l-1,3-arabinofuranosyl residues from arabinoxylan. These enzymes have been found in many microorganisms, and reports of their purification and gene cloning have been published (20). The filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei is one of the most potent cellulolytic organisms and also produces a xylanolytic system, which contains multiple enzyme activities required for the complete degradation of xylan (1, 10).

An α-AF from T. reesei has been purified and partially characterized, and its cDNA has been cloned (14, 18). In this fungus, l-arabinose was reported to induce the enzyme (11, 12). In our preliminary results, we observed that α-AF activity was also induced by l-sorbose, which is an excellent inducer for the production of cellulase and xylanase by T. reesei PC-3-7, a cellulase-hyperproducing mutant (9, 25). Comparison of the purified α-AF induced by l-sorbose with that induced by arabinose proved that the enzymes differed in their molecular masses. In the present paper, it is reported that the enzyme with the lower molecular mass is the truncated form of the enzyme with the higher molecular mass. It is shown that the latter possesses a noncatalytic XBD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

The strain used in this study was T. reesei PC-3-7, a cellulase-hyperproducing mutant with an enhanced response to l-sorbose as an inducer (9); it was obtained from Kyowa Hakko Kogyo Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). This strain was maintained on a potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco) slant, and the conidia were obtained from a PDA plate culture. Induction experiments were performed in a resting cell system (16). To obtain mycelium, 106 conidia of T. reesei PC-3-7 were inoculated into 50 ml of basal medium with 0.3% (wt/vol) glucose as a carbon source (9) and were incubated for 48 h at 28°C with vigorous shaking (220 rpm). For induction, the mycelium was washed twice with 0.9% (wt/vol) NaCl and the dry weight of the mycelium was determined. The washed mycelium was transferred into an induction medium containing l-sorbose (500 μg/ml) or α-sophorose (250 μg/ml) as previously described by Kawamori et al. (9), giving a final dry weight of about 2.0 mg/ml for the mycelium. The induction was carried out for 24 h at 28°C on a reciprocal shaker at 120 strokes per min. For purification of α-AF, the mycelium obtained was transferred into 800 ml of the induction solution containing l-sorbose in a 2-liter Erlenmeyer flask and was incubated for 60 h at 28°C with shaking (220 rpm).

Enzyme assay.

α-AF and β-d-xylosidase activities were measured by monitoring the release of p-nitrophenol at 420 nm from p-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinofuranoside (pNPA; Sigma) and p-nitrophenyl-β-d-xylopyranoside (pNPX; Sigma), respectively (4). The α-AF activity that liberated α-arabinofuranose from xylan was measured as the amount of reducing sugar liberated during the hydrolysis of oat spelt xylan (Sigma) by the Somogyi-Nelson method (19). β-d-Glucosidase, α-l-arabinopyranosidase, α-d-galactosidase, β-d-mannosidase, and β-d-galactosidase activities were determined by liberation of p-nitrophenol or o-nitrophenol from p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-α-l-arabinopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-mannopyranoside, and o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (all from Sigma), respectively (4, 13, 17). Endoglucanase, xylanase, mannanase, laminarinase, and amylase activities were measured by evaluating the amounts of reducing sugar released from carboxymethyl cellulose (Wako, Tokyo, Japan), oat spelt xylan, locust bean gum (Fluka), laminarin (Sigma), and soluble starch (Wako) by the Somogyi-Nelson method (5, 6, 9, 19, 25). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that liberated 1 μmol of product from the substrate.

The Km and Vmax values for α-AF were determined from Lineweaver-Burk plots using pNPA as a substrate at concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 5.0 mM.

Enzyme purification.

All operations were carried out at 4°C. The crude enzyme was precipitated from 800 ml of the filtrate obtained from the induction medium with ammonium sulfate (40 to 60% saturation) and was dissolved in 20 ml of 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 30% saturated ammonium sulfate. The sample was then applied onto a column (1.5 by 2.8 cm) of phenyl Sepharose HP (Pharmacia) which had been equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed with the buffer, and the enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient of 30 to 0% saturated ammonium sulfate in the buffer at a flow rate of 20 ml/h. The α-AF fractions eluted with 17% saturated ammonium sulfate were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration (PM-10; Amicon). The concentrate was applied onto a column (1 by 96 cm) of Sephacryl S-100 HR (Pharmacia) previously equilibrated with 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 300 mM NaCl and was eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 14 ml/h. Fractions exhibiting α-AF activity were pooled, desalted, and concentrated, and the buffer was changed to 10 mM citrate-phosphate (pH 6.0), by ultrafiltration (PM-10). The sample was subjected to ion-exchange chromatography on a column of SP-Sepharose FF (Pharmacia) (0.8 by 2 cm) previously equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed with the buffer and eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.2 M NaCl in the same buffer at a flow rate of 4 ml/h. The fractions with α-AF activity were pooled and then desalted and concentrated by ultrafiltration (PM-10). The sample was applied onto a Q-Sepharose FF column (0.8 by 2 cm) previously equilibrated with the same buffer (pH 6.0). The column was washed with the same buffer at a flow rate of 4 ml/h. The resulting active fraction without adsorption was concentrated and used as the purified enzyme preparation throughout this study.

The α-AF with a molecular mass of 35 kDa (AF35) was preliminarily purified by SP-Sepharose FF column chromatography (pH 4.0) as the first step after precipitation with ammonium sulfate. As this enzyme was suggested to be an acid protease cleavage product of AF53, the ammonium sulfate precipitate (40 to 60% saturation) was dissolved in a 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.0) and then incubated at 28°C for 24 h for digestion. The enzyme was thereafter purified as described above for AF53.

Endoglucanase I (EGI) used in this experiment was purified from a crude preparation of T. reesei cellulase (Kyowa Hakko) as previously described by Morikawa et al. (15).

pH and temperature optima and stability.

The optimum temperature for the activity against pNPA was determined by performing the assays (see above) at various temperatures between 30 and 70°C in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0. For determination of temperature stability, the purified enzyme preparation in 10 mM citric acid–Na2HPO4 buffer (30 μg of AF53/ml; 50 μg of AF35/ml), pH 6.0, was incubated at different temperatures (0 to 60°C) for 1 h, and aliquots of the samples were thereafter assayed for activity. The optimum pH value was determined by monitoring the activity at different pH values (3.0 to 11.0) at 50°C. The following buffers were used: 0.2 M citric acid–Na2HPO4 (pH 3.0 to 8.0) and 0.2 M H3BO4–Na2CO3 (pH 7.0 to 11.0). For pH stability, the preparation in 0.2 M citric acid–Na2HPO4 buffers (pH 3.0 to 8.0) or in 0.2 M H3BO4–Na2CO3 (pH 7.0 to 11.0) (3.0 μl of AF53/ml; 5.0 μg of AF35/ml) was incubated at 25°C for 1 h. Aliquots of the samples were assayed immediately for activity against pNPA at pH 4.0.

Acid and pepsin treatments (pH 3.0).

The ammonium sulfate-precipitated sample was dissolved in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0), and the buffer was changed to 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.0) by ultrafiltration. After incubation at 28°C for 24 h, the samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Purified AF53 (12.6 μg) was incubated with pepsin (1.4 μg) in 100 μl of 10 mM citric acid–Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 3.0) at 37°C for 0.5, 2, 4, and 12 h. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 μl of 50 μM pepstatin A in 1 M citric acid-NaOH buffer (pH 7.0). The digestion products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and their activities against pNPA and oat spelt xylan were measured.

Substrate-binding assay.

Oat spelt xylan and crystalline cellulose (Avicel) used for the substrate-binding assay were prepared as follows: 0.75 g was washed three times with 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0), and the resulting pellet was suspended in the same buffer to give suspensions of 22.2 mg/ml (xylan) or 29.9 mg/ml (Avicel). For the substrate-binding assay, 50 μl of AF53, AF35, or EGI at various concentrations (0 to 12, 0 to 6, and 0 to 20 μg/ml, respectively) was mixed with 450 μl of the substrate suspensions and held at 4°C for 10 min. This mixture contained bovine serum albumin (BSA) at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml to prevent inactivation caused by dilution. The supernatant was then separated from the insoluble substrate by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 2 min. Immediately after centrifugation, an aliquot of the supernatant was taken, and the activity was assayed.

For analysis of proteins adsorbed to xylan, BSA was omitted from the sample mixture. The pellet after incubation for binding was washed three times with 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) at 4°C, and the resulting pellet was suspended in 50 μl of the SDS-PAGE sample buffer, immersed in a boiling water bath for 2 min, and then analyzed by SDS–PAGE (10% polyacrylamide).

Other analytical methods.

Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (3) with BSA as a standard. SDS-PAGE was carried out by using a MINI-PROTEAN II Electrophoresis Cell (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s manual. The proteins in the gel were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of both of the purified enzymes were identified by automated Edman degradation using a Shimadzu PPSQ-21 protein sequencer.

RESULTS

Induction of α-AF activity by l-sorbose and its purification.

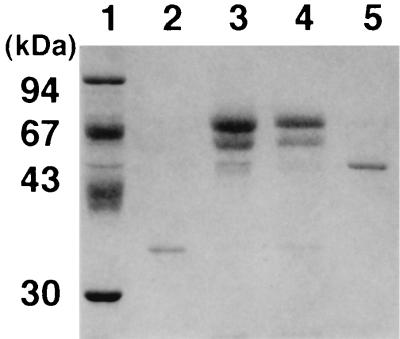

As shown in Table 1, l-sorbose induced α-AF activity, while α-sophorose did not. In order to compare this l-sorbose-induced α-AF with the previously reported enzyme, we purified it, using SP-Sepharose FF chromatography as the first step. The molecular mass of the purified enzyme was 35 kDa when it was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (data not shown), which is in contrast to the previously reported 53 kDa (18). We speculated that proteolysis of the enzyme by an acid protease may have occurred during the SP-Sepharose chromatography step, because some of the SDS-PAGE bands of l-sorbose-induced proteins disappeared when the proteins were incubated under acidic conditions (pH 3.0) (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4).

TABLE 1.

Glycanase activities induced by l-sorbose and α-sophorose by using a washed mycelium of T. reesei PC-3-7

| Enzyme | Activity (U/mg [dry wt] of mycelium)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| l-Sorbose | α-Sophorose | |

| CMCasea | 1.43 | 1.36 |

| β-d-Glucosidase | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Xylanase | 1.43 | 0.75 |

| β-d-Xylosidase | 0.01 | 0 |

| α-AF | 0.36 | 0.01 |

| α-l-Arabinopyranosidase | 0 | 0 |

| α-d-Galactosidase | 0 | 0.01 |

| β-d-Galactosidase | 0 | 0 |

| Mannanase | 0 | 0 |

| β-d-Mannosidase | 0 | 0 |

| Laminarinase | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Amylase | 0.03 | 0.03 |

CMCase, carboxymethyl cellulase.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of the purified α-AFs and the acid-treated sample (pH 3.0) of the crude enzyme induced by l-sorbose. Lane 1, marker proteins (Pharmacia) containing soybean trypsin inhibitor (20 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), BSA (67 kDa), and phosphorylase (94 kDa); lane 2, purified AF35 (2.0 μg of protein); lane 3, crude enzyme after an (NH4)2SO3 precipitation step (12 μg of protein); lane 4, acid-treated crude enzyme (11 μg of protein); lane 5, purified AF53 (2.1 μg of protein).

To avoid proteolysis of the enzyme, we changed the purification step as described in Materials and Methods. The α-AF was purified 32-fold to a specific activity of 120 U/mg of protein with pNPA as a substrate. This enzyme preparation yielded a single band in SDS-PAGE, from which its molecular mass was estimated to be 53 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 5). We named this enzyme AF53. We also purified the enzyme after proteolysis by incubation at pH 3.0. The purification is summarized in Table 2. The enzyme incubated at pH 3.0 was purified 65-fold to a specific activity of 196 U/mg of protein. The molecular mass of this enzyme was determined by SDS-PAGE as 35 kDa (Fig. 1, lane 2), which is in a good agreement with that of the preliminarily purified enzyme described above. We designated this enzyme AF35. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of both enzymes were identical, G-P-X-D-I-Y-S-A-G-G (where “X” stands for an undetermined amino acid), and were also identical to that of the α-AF earlier purified from this fungus (14). Therefore, these results show that AF35 is most probably a C-terminally truncated form of AF53.

TABLE 2.

Purification of AF35

| Purification step | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture broth | 121 | 363 | 3.00 | 100 | 1.00 |

| Acid treatment after (NH4)2SO4 (40 to 60%) precipitation | 67.8 | 228 | 3.36 | 63 | 1.12 |

| Phenyl Sepharose HP | 1.73 | 211 | 122 | 58 | 40.7 |

| Sephacryl S-100 HR | 1.19 | 204 | 171 | 56 | 57.0 |

| SP-Sepharose FF | 0.54 | 103 | 191 | 28 | 63.7 |

| Q-Sepharose FF | 0.48 | 94 | 196 | 26 | 65.3 |

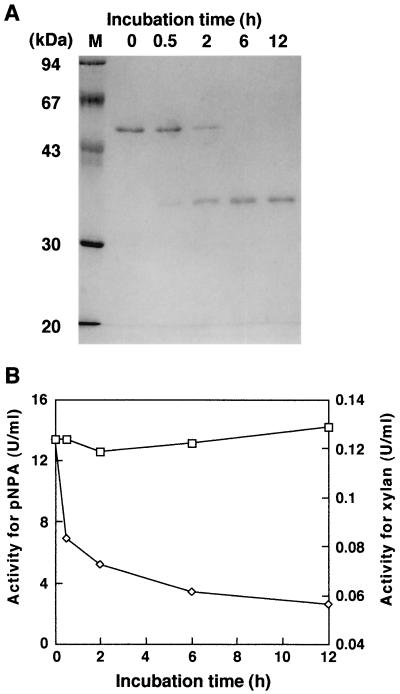

Time course of digestion of AF53 by pepsin.

In vitro proteolysis of purified AF53 with pepsin was performed to verify the conversion of AF53 to AF35. As shown in Fig. 2A, a decrease in the 53-kDa band was accompanied by an increase in the 35-kDa protein band on SDS-PAGE. After an incubation of 6 h, the 53-kDa protein band was completely converted to the 35-kDa band, and for a further 12 h no proteolysis of the 35-kDa band was observed. The enzyme activity against pNPA did not change during proteolysis, whereas that against xylan strongly decreased (Fig. 2B). The time course of the activity with xylan coincided with that of the conversion of the 53-kDa band to a 35-kDa band on SDS-PAGE. Therefore, the conversion of the 53-kDa protein to a 35-kDa protein by pepsin is likely responsible for the decrease in the activity against xylan.

FIG. 2.

(A) In vitro proteolysis of AF53 by pepsin. The course of the remaining protein after the pepsin treatment was followed by SDS-PAGE. Lane M, marker proteins. Numbers above the lanes are incubation times (in hours). (B) Time course of the α-AF activities through in vitro proteolysis of AF53 by pepsin. The hydrolysis activities for pNPA (□) and oat spelt xylan (◊) were plotted.

Enzymological analysis of α-AFs.

The enzymological properties of both α-AFs are summarized in Table 3. The influences of pH and temperature on enzyme activity and stability were largely similar for the two enzymes. The Km and catalytic constant (kcat) values of AF53 and AF35 were 0.9 and 1.1 mM and 269 and 259 s−1, respectively, although the Vmax values of the two enzymes were different from each other. However, the most striking difference between the two enzymes was that the specific activity of AF35 against oat spelt xylan was significantly lower (0.061 U/mg of protein) than that of AF53 (2.6 U/mg of protein) (Table 4). AF35 also exhibited high activities against pNPA and pNPX, as did the 53 kDa enzyme (196 and 1.8 U/mg of protein and 120 and 1.3 U/mg of protein, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Enzymatic properties of AF53 and AF35a

| Characteristic | AF53 | AF35 |

|---|---|---|

| Km (mM) | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Vmax (U/mg) | 304 | 444 |

| kcat (s−1) | 269 | 259 |

| Optimum pH | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Stable pH | 4.5–7.0 | 4.0–7.0 |

| Optimum temp (°C) | 60 | 60 |

| Stable temp (°C) | <40 | <40 |

pNPA was used as a substrate.

TABLE 4.

Substrate specificities of AF53 and AF35

| Enzyme | Sp act (U/mg) against:

|

Xylan/pNPA (relative %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pNPA | pNPX | Oat spelt xylan | ||

| AF53 | 120 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 100 |

| AF35 | 196 | 1.8 | 0.061 | 1.4 |

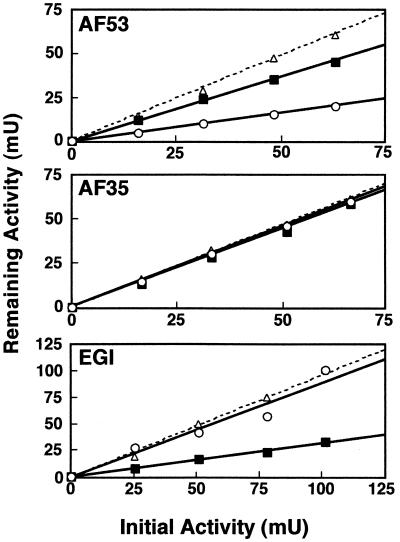

Xylan-binding assay.

To investigate the difference in action on xylan between the two enzymes, their adsorption on xylan and Avicel was tested. T. reesei EGI containing a CBD could bind to Avicel (70% of the added enzyme was bound) but bound to xylan with less avidity (less than 25% was bound) under the conditions used (Fig. 3). The activity of AF53 in the supernatant of the xylan solution decreased appreciably, to 32% of the initially added activity, whereas that in the supernatant of the Avicel solution was reduced only to 74% (Fig. 3). On the other hand, almost all the activity of AF35 remained in both supernatants. Furthermore, the AF53 adsorbed on the xylan was eluted with SDS and detected by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Adsorption of the purified enzymes on insoluble glycans. The remaining activities in the supernatant were determined by the standard assay. The concentrations of oat spelt xylan and Avicel in the binding mixture were 20 and 27 mg/ml, respectively, and various concentrations of the AF53, AF35, and EGI in the mixture (0 to 1.2, 0 to 0.6, and 0 to 2.0 μg/ml, respectively) were used. Symbols represent activity after incubation with oat spelt xylan (○), with Avicel (■), and without substrate (▵).

FIG. 4.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the xylan-bound enzymes. The xylan-bound protein was detected by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, purified AF53; lane 2, xylan-bound fraction of AF53; lane 3, purified AF35; lane 4, xylan-bound fraction of AF35.

DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that l-sorbose is an excellent inducer of cellulase and xylanase formation of T. reesei PC-3-7 (9, 25), but we have been unaware whether the compound also triggers the production of other glycanases. Therefore, we compared the glycanase activities induced by l-sorbose and by α-sophorose, the most potent cellulase inducer, in T. reesei PC-3-7. The results showed that l-sorbose induced higher hemicellulase activities than α-sophorose did, particularly in the case of α-AF, which was formed only by l-sorbose. Recent studies showed that l-arabinose and arabitol induced α-AF expression in T. reesei (11, 12). We show that l-sorbose is also an inducer of α-AF. The l-sorbose-inducible α-AF was therefore purified to ascertain that it was the same enzyme as that induced by l-arabinose. In the purification step, two enzymes, AF35 and AF53, were obtained with and without the acid treatment, respectively. These enzymes share some enzymological properties, such as effects of pH and temperature on enzyme activity and stability, and kinetic properties (Km and kcat) for pNPA. Both enzymes purified in this study also possessed a slight β-d-xylosidase activity, which could be measured by using pNPX as a substrate (Table 4). The β-d-xylosidase activities of AF53 and AF35 were about 1% of the α-AF activities for pNPA, which agrees well with the findings for the T. reesei α-AF previously reported (18). Moreover, the N-terminal amino acid sequences of the two purified enzymes were identical to that of the deduced amino acid from the cloned α-AF cDNA from T. reesei RUT C-30 (14). These results clearly indicated that the enzymes were identical to that previously reported for this fungus (14, 18).

Proteolysis of AF53 by the acid proteases led to a decrease in the molecular mass to 35 kDa and to reduction of the activity against xylan, whereas the activities against pNPA and pNPX were not altered (Tables 3 and 4). The possibility that the AF53 activity on xylan is due, at least in part, to a very slight amount of contaminating xylanase activity cannot be ruled out. For further characterization of the activities of AF53 and AF35 on xylan, it is preferable to use recombinant enzymes produced by a non-xylanase-producing host. A reduction of activity for insoluble substrates as a result of proteolysis has been shown in some polysaccharide-degrading enzymes with modular structures (24). These modular glycanases usually possess a catalytic domain responsible for the hydrolysis reaction itself and a substrate-binding domain promoting adsorption of the enzyme onto insoluble substrates. The two domains of the glycanases are joined by linker peptides (24). In cellobiohydrolase I of T. reesei, limited proteolysis by papain separated the CBD from the catalytic domain, which is fully active on small soluble substrates but has strongly reduced activity against insoluble celluloses (Avicel and phosphoric-acid-swollen cellulose) (22). In our study, AF35, the truncated form in which the C-terminal half of AF53 was removed, lost the binding activity for xylan. Therefore, we suppose that the α-AF from T. reesei is a modular glycanase containing a catalytic domain and a substrate-binding domain. This noncatalytic domain of the enzyme has a higher affinity for xylan than for crystalline cellulose (Avicel). Therefore, it is regarded as an XBD rather than a CBD. Most of the substrate-binding domains of hemicellulases are commonly CBDs. On the other hand, two bacterial xylanases, TfxA from T. fusca and XYLD from C. fimi, and an α-AF (AbfB) from S. lividans were thought to possess XBDs. The XBDs of bacterial xylanases have some homology to CBDs of the same origin (2, 7, 8, 23). Unfortunately, the AF53 XBD was not isolated when AF53 was treated with pepsin because no distinct band appeared except for the AF35 band. Furthermore, no region homologous to the CBD and/or XBD and linkers was found in the deduced amino acid sequence of the α-AF C-terminal half from T. reesei (14). In preliminary experiments performed with various ionic strengths, the amounts of AF53 that bound to xylan varied with the ionic strength (28% of the activity initially added was bound to xylan in the buffer with a concentration of 200 mM), as reported by Tenkanen et al. (21). It is postulated, therefore, that electrostatic interactions may have a significant role in binding to oat spelt xylan. However, AF35 cannot be bound to xylan at all under the same conditions, suggesting that the AF53 C-terminal half without catalytic function can be bound to xylan. This indicates that the type of the XBD would be different from that of CBDs reported so far. In any case, AF53 is, to our knowledge, the first eukaryotic hemicellulase containing an XBD.

We have cloned the α-AF gene, using the PCR technique, from the chromosomal DNA of T. reesei PC-3-7. Now we are trying to express this gene in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and to use this expression system to determine the precise region of the gene corresponding to the XBD in the C-terminal half of AF53.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks go to H. Watanabe for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work has been supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (A), no. 11132218, from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biely P, Tenkanen M. Enzymology of hemicellulose degradation. In: Harman G E, Kubicek C P, editors. Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 2. Enzymes, biological control and commercial applications. London, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 1998. pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black G W, Hazlewood G P, Millward-Sadler S J, Laurie J I, Gilbert H J. A modular xylanase containing a novel non-catalytic xylan-specific binding domain. Biochem J. 1995;307:191–195. doi: 10.1042/bj3070191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Hayn M, Esterbauer H. Purification and characterization of two extracellular β-glucosidases from Trichoderma reesei. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1121:54–60. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90336-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke J H, Rixon J E, Ciruela A, Gilbert H J, Hazlewood G P. Family-10 and family-11 xylanases differ in their capacity to enhance the bleachability of hardwood and softwood paper pulps. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:177–183. doi: 10.1007/s002530051035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de la Cruz J, Pintor-Toro J A, Benítez T, Llobell A, Romero L C. A novel endo-β-1,3-glucanase, BGN13.1, involved in the mycoparasitism of Trichoderma harzianum. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6937–6945. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6937-6945.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupont C, Roberge M, Shareck F, Morosoli R, Kluepfel D. Substrate-binding domains of glycanases from Streptomyces lividans: characterization of a new family of xylan-binding domains. Biochem J. 1998;330:41–45. doi: 10.1042/bj3300041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irwin D, Jung E D, Wilson D B. Characterization of a Thermomonospora fusca xylanase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:763–770. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.763-770.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawamori M, Morikawa Y, Takasawa S. Induction and production of cellulases by l-sorbose in Trichoderma reesei. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1986;24:449–453. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ken K, Wong Y, Saddler N J. Trichoderma xylanases, their properties and application. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1992;12:413–435. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristufek D, Hodits R, Kubicek C P. Coinduction of α-l-arabinofuranosidase and α-d-galactosidase formation in Trichoderma reesei RUT C-30. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;115:259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubicek C P, Penttilä M E. Regulation of production of plant polysaccharide degrading enzymes by Trichoderma. In: Harman G E, Kubicek C P, editors. Trichoderma and Gliocladium, vol. 2. Enzymes, biological control and commercial applications. London, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 1998. pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margolles-Clark E, Tenkanen M, Luonteri E, Penttilä M. Three α-galactosidase genes of Trichoderma reesei cloned by expression in yeast. Eur J Biochem. 1996;240:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0104h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margolles-Clark E, Tenkanen M, Nakkari-Setälä T, Penttilä M. Cloning of genes encoding α-l-arabinofuranosidase and β-xylosidase from Trichoderma reesei by expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3840–3846. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3840-3846.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morikawa Y, Takahashi A, Yano K, Yamasaki M, Okada H. A low molecular weight endoglucanase from Trichoderma reesei. In: Shimada K, Hoshino S, Ohmiya K, Sakka K, Kobayashi Y, Karita S, editors. Genetics, biochemistry and ecology of lignocellulose degradation. Tokyo, Japan: UniPublisher Co., Ltd.; 1994. pp. 458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morikawa Y, Ohashi T, Mantani O, Okada H. Cellulase induction by lactose in Trichoderma reesei PC-3-7. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;44:106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nevalainen K M H. Induction, isolation and characterization of Aspergillus niger mutant strains producing elevated levels of β-galactosidase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:593–596. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.3.593-596.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poutanen K. An α-l-arabinofuranosidase of Trichoderma reesei. J Biotechnol. 1988;7:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somogyi M. Notes on sugar determination. J Biol Chem. 1952;195:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunna A, Antrankian G. Xylanolytic enzymes from fungi and bacteria. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1997;17:39–67. doi: 10.3109/07388559709146606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tenkanen M, Buchert J, Viikari L. Binding of hemicellulases on isolated polysaccharide substrates. Enzyme Microbiol Technol. 1995;17:499–505. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomme P, van Tilbeurgh H, Pettersson G, van Damme J, Vandekerckhove J, Knowles J, Teeri T, Claeyssens M. Studies of the cellulolytic system of Trichoderma reesei QM9414. Analysis of domain function in two cellobiohydrolases by limited proteolysis. Eur J Biochem. 1988;170:575–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent P, Shareck F, Dupont C, Morosoli R, Kluepfel D. New α-l-arabinofuranosidase produced by Streptomyces lividans: cloning and DNA sequence of the abfB gene and characterization of the enzyme. Biochem J. 1997;322:845–852. doi: 10.1042/bj3220845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warren R A J. Microbial hydrolysis of polysaccharides. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:183–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu J, Nogawa M, Okada H, Morikawa Y. Xylanase induction by l-sorbose in a fungus, Trichoderma reesei PC-3-7. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1555–1559. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]