Abstract

Background

Increased weight gain and decreased physical activity have been reported in some populations since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, but this has not been well characterized in pregnant populations.

Objectives

Our objective was to characterize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated countermeasures on pregnancy weight gain and infant birthweight in a US cohort.

Methods

Washington State pregnancies and births (1 January, 2016 to 28 December, 2020) from a multihospital quality improvement organization were examined for pregnancy weight gain, pregnancy weight gain z-score adjusted for pregestational BMI and gestational age, and infant birthweight z-score, using an interrupted time series design that controls for underlying time trends. We used mixed-effect linear regression models, controlled for seasonality and clustered at the hospital level, to model the weekly time trends and changes on 23 March, 2020, the onset of local COVID-19 countermeasures.

Results

Our analysis included 77,411 pregnant people and 104,936 infants with complete outcome data. The mean pregnancy weight gain was 12.1 kg (z-score: −0.14) during the prepandemic time period (March to December 2019) and increased to 12.4 kg (z-score: −0.09) after the onset of the pandemic (March to December 2020). Our time series analysis found that after the pandemic onset, the mean weight gain increased by 0.49 kg (95% CI: 0.25, 0.73 kg) and weight gain z-score increased by 0.080 (95% CI: 0.03, 0.13), with no changes in the baseline yearly trend. Infant birthweight z-scores were unchanged (−0.004; 95% CI: −0.04, 0.03). Overall, the results were unchanged in analyses stratified by pregestational BMI categories.

Conclusions

We observed a modest increase in weight gain after the onset of the pandemic among pregnant people but no changes in infant birthweights. This weight change could be more important in high BMI subgroups.

Keywords: pregnancy, gestational weight gain, infant birthweight, COVID-19, interrupted time series

Introduction

In response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, leaders introduced sweeping changes to health systems and service delivery, policies restricting individuals’ travel outside the home, and closures of schools and workplaces [1]. These have been associated with changes in exercise and nutrition, weight gain and weight loss [[2], [3], [4], [5]], and worsening mental health [6, 7], compared with the prepandemic time period. However, the effects of the pandemic have not been uniform, with disproportionate impacts being felt by those living in poverty, those with existing chronic health conditions, and racialized groups [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted lifestyles and increased stress in pregnant women and birthing people [6]. Antenatal stress may alter weight gain in pregnancy [[9], [10], [11]]; furthermore, pandemic-related stress could have unique impacts [12] on weight change trajectories during pregnancy [13]. Along with increased stress and disrupted lifestyles, health care delivery in the United States has changed, with increased reliance on telehealth and longer spacing between prenatal care visits [14]. These may have decreased the access to nutritional counseling and serial weight assessments during prenatal care. At the same time, food insecurity increased in the United States after the onset of the pandemic [15], and families may have had to increase their reliance on shelf-stable processed foods [16, 17]. This may be particularly important for families living in poverty as both food insecurity and increased use of processed foods have been linked to higher rates of obesity [18].

Weight gain during pregnancy is used as an indicator of nutritional health. Excess pregnancy weight gain is associated with a higher risk of large birthweight infants [19, 20] and pregnancy-related diseases (e.g., hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes) [21, 22] and is a strong determinant of longer-term obesity [23]. We hypothesized that the pandemic-associated countermeasures and stresses, which have impacted weight status among nonpregnant people [[2], [3], [4], [5]], may have altered pregnancy weight gain and infant birthweights compared with the prepandemic times. Increases in maternal obesity or infant birthweights could have long-term health consequences by impacting the rates of postpregnancy obesity, childhood obesity, and chronic diseases such as diabetes. Therefore, we studied births from a multihospital initiative in Washington State, where some of the earliest United States cases of COVID-19 were detected. We aimed to assess the combined impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, pandemic-related policies, and health system disruptions on changes in weight during pregnancy and on infant birthweight.

Methods

Subjects

We used data from a perinatal quality improvement initiative—the Obstetrical Care Outcomes Assessment Program—from 1 January, 2016 to 31 December, 2020, representing approximately one-third of the births in Washington State. The database was populated through both electronic health records and chart abstraction with real-time quality checks and validation [24]. This study was reviewed by the University of British Columbia Harmonized ethics review board and approved as a minimal-risk study (#H20-00741).

We restricted to singleton pregnancies with births that occurred at or beyond 24 weeks of gestation. We excluded records with missing or implausible weight measurements (<30 kg or >350 kg), with no early or prepregnancy weight measurement (<14+0 wk), with a last measured weight taken >28 d from delivery, and with missing or implausible gestational weight gain z-score (>6 SD or less than −6 SD) using the z-score reference of Santos et al. [25]. We excluded infants with missing birthweight or sex, implausible infant birthweight according to the criteria from the study by Alexander et al. [26] and z-scores [using the z-score chart from the study by Aris et al. [27]] as per the approach of Basso and Wilcox [28] (<5 SD or more than −5 SD for term births, >4 SD or less than −3 SD for preterm births).

Study context

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States was in Washington State on January 21, 2020. By 12 March, 2020, social gatherings were banned and all educational institutions were closed, and on 23 March, 2020, the state governor issued a 2-wk “stay-at-home” order. Most broad restrictions on public life remained until early June 2020, followed by a temporary loosening of some restrictions until September 2020, when there was a resurgence of COVID-19 cases. Schools were closed for in-person learning throughout 2020. Hospital-level and health care provider–level infection control countermeasures were based on guidelines from national professional associations [29]. COVID-19 public health and policy actions in Washington State were quantified using publicly available data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker [1] to identify 3 time periods of interest: 1) a prepandemic period (1 January, 2016, to 23 February, 2020), 2) a transition period where new policies were rapidly implemented (24 February, 2020, to 23 March, 2020), and 3) a steady state period where a few pandemic measures were relaxed but most policies were maintained consistently across the state (24 March, 2020, to 28 December, 2020) (Supplemental Figure 1).

Measurements

Pregnancy weight gain, z-scores, and infant birthweight z-scores

We examined pregnancy weight gain using 2 different measures: 1) total pregnancy weight gain in kilograms, defined as the difference between the last weight before delivery (within 28 days of delivery) and pre or early-pregnancy weight (<14+0 wk) and 2) pregnancy weight gain z-scores, which were standardized for pregestational BMI and gestational age using a weight gain for gestational age chart [25, 30] that was derived from >200,000 pregnant women from 33 cohorts in Europe, North America, and Oceania. The pre- or early-pregnancy weights were based on a self-reported prepregnancy weight or the measured weight at the first prenatal visit. The last pregnancy weight before delivery was recorded at the time of admission in labor. We calculated the pregestational BMI using the pre- or early-pregnancy weight and height (cm) [31]. We calculated infant birthweight z-scores, standardized for a gestational week at birth and infant sex, using the US natality-based reference charts by Aris et al. [27, 32].

Demographic and obstetric characteristics

We obtained chart-abstracted data for self-reported race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian or Pacific Islander, Native, other, or mixed race), maternal age at delivery (y), parity (nulliparous [no prior term delivery] or multiparous), pregestational BMI, height, gestational age at delivery (wk, based on obstetric estimated due date), hospital site of delivery, insurance payor type (Medicaid vs. others), rural–urban commuting areas [33] collapsed to 2-levels (rural vs. nonrural) [34], and the Distressed Communities Index [35] (DCI) quintiles (prosperous, comfortable, mid-tier, at risk, and distressed) from the data registry. The DCI quintiles combine 7 socioeconomic indicators into a measure of economic well-being in each zip code relative to its peers [35]. The pregestational BMI (kg/m2) was categorized as underweight or normal (<24.9); overweight (25–29.9); and grade 1 (30–34.9), grade 2 (35–39.9), or grade 3 (≥40) obesity.

Statistical analyses

We used an interrupted time series design [36, 37] to assess pandemic-associated changes in the outcomes while controlling for underlying trends by week of study time. Interrupted time series is one of the strongest quasi-experimental designs to evaluate the effects of a policy, an intervention, or a widespread system’s impact. In this analysis, a time series establishes the underlying trend, and 2 line segments are fitted simultaneously, separated by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The hypothetical scenario if the impact had not occurred is referred to as the “counterfactual.”

The time period of our study was 1 January, 2016, to 28 December, 2020 (261 complete weeks). We chose the COVID-19 pandemic onset as beginning on 23 March, 2020, which we identified as the start of a “steady state” of pandemic-related policies and restrictions in Washington State. Births in a 4-wk period [37] from 24 February, 2020 to 22 March, 2020, were excluded for 2 reasons. First, we hypothesized that an effect of the pandemic on either weight gain or infant birthweight would not occur immediately and that ≥2 wk of pandemic-associated policies would be needed to observe meaningful and detectable weight gain. Second, there were rapid changes in the COVID-19 response policies during this time segment. Excluding births in this 4-wk period meant that for pregnant people who delivered after 23 March 2020, the total weight gain would include ≥2 wks of the pandemic. We hypothesized that the pandemic could cause both a change in level and in the time trend [37] in our outcomes because the impact of the pandemic on weight at the population level could be immediate if diet or activity changed immediately, or could be delayed if there was a more gradual overall change in behavior.

Potential confounders were identified using a directed acyclic graph and from prior studies [[38], [39], [40]]. Pregnancy weight gain was adjusted a priori for gestational age at delivery because gestational duration directly impacts an individual’s opportunity to gain weight [41]. Neither weight gain z-scores nor infant z-score models were adjusted for gestational age because z-scores were gestational age specific. We considered Medicaid insurance payor, rural residence, distressed community indices, race/ethnicity, age, parity, antenatal health care professional type (midwife vs. family practice vs. obstetrician), and pregestational BMI as potential confounders and plotted time series of all potential confounders. If we noted discontinuities at the pandemic onset and if there was no plausible association between that factor and the pandemic, this justified inclusion in the model.

We also adjusted for seasonal trends [42, 43] for both pregnancy weight gain and infant birthweight [40, 44]. Seasonality can be an important confounder in perinatal outcomes, as it may impact both birth rates and exposure-outcome relationships [45]. We used week of conception [45] rather than week of delivery to estimate the impact of season. We also plotted the mean data by the month of conception and superimposed by year. Adjustment for seasonal trends used a single sine term, as this provided the best model fit based on the lowest Akaike’s Information Criterion compared with other approaches (multiple sine-cosine pairs and month indicator variables).

We included, a priori, random effect terms for hospital intercept, slope, and residuals to allow for hospital-level variation in baseline outcomes and over time. To account for sampling uncertainty and repeated measures within the sample study population, parametric bootstrapping techniques were used to calculate CIs. All models were analyzed as generalized linear regression mixed-effect models in R (version 4.0.5) [46]. The final model specification is included in the Supplemental Methods.

Sensitivity analyses

We hypothesized that the pandemic might differentially impact those who were at the higher end of the population distribution of pregnancy weight gain. To assess this, we examined the 90th percentile of all outcomes in quantile regression models [47] using similar interrupted time series models. We also repeated the analyses stratified by pregestational BMI categories. Lastly, we examined the effect of increased duration of exposure to the pandemic by excluding 9 wk of births, from 23 February 2020 to 27 April, 2020, and 15 wk of births, from 23, February 2020 to 8 June, 2020, thereby including pregnancies with longer exposure to pandemic-associated countermeasures.

Results

Study population

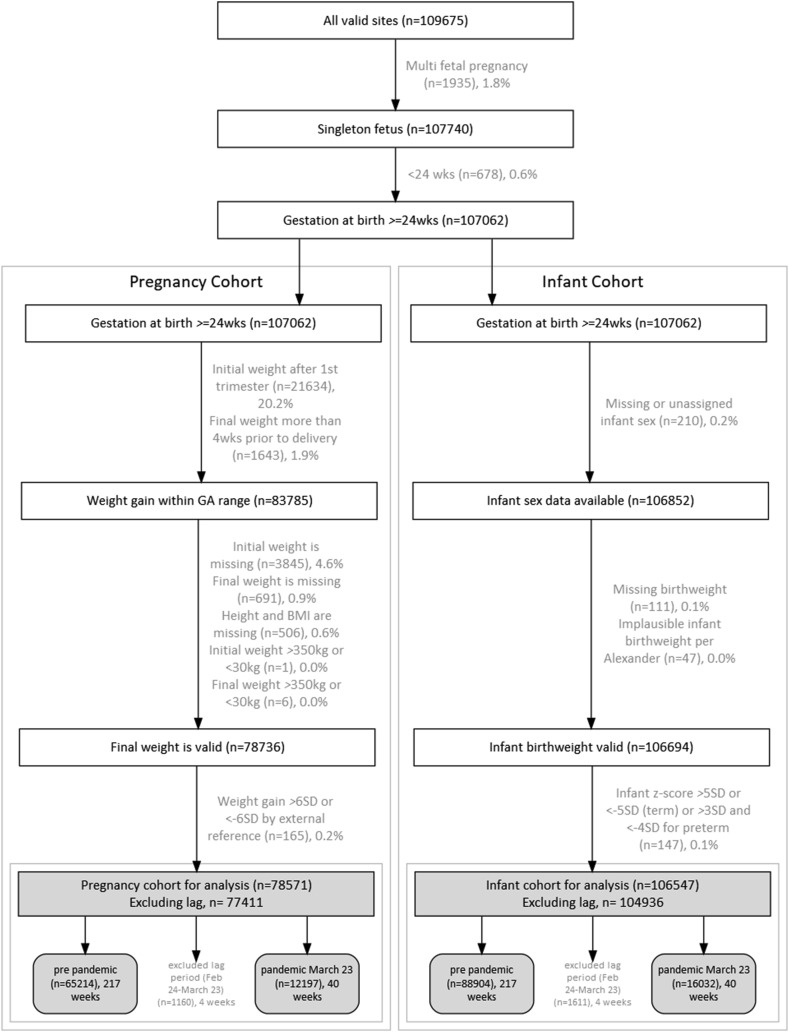

There were 107,062 singleton pregnancies and infants (>24 wk gestational age) during the study period (Figure 1 ). Overall, 23,277 (21.7%) pregnancies were missing weight gain data because their weight data were collected after 14 wk of pregnancy and/or >28 d before delivery, and 5214 (6.2%) pregnancies were excluded because of missing or implausible weight data. Only 515 (0.5%) infants were excluded because of missing or implausible birthweight data. The final sample included 77,411 pregnancies and 104,936 infants. The excluded cases were not biased by the pandemic time period (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of study population and exclusions for a Washington State study of gestational weight gain, infant birthweight, and the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (1 January, 2016 to 28 December, 2020; final sample = 77,411 pregnancies and 104,936 infants). (Excluded data in light gray text). GA, gestational age.

Population characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the pregnancy and infant cohorts showed minor differences between the time periods. Specifically, the pandemic period included a greater proportion of nulliparas, individuals beginning pregnancy with obesity, and individuals with older age at delivery. The time series graphs for demographic or obstetric covariates revealed that any apparent differences were because of gradual trends over time rather than abrupt changes at the pandemic onset; thus, no additional covariates were included in the regression models (Table 1, Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Pregnancy cohort demographic characteristics and outcomes by prepandemic (1 January, 2016 to 23 February, 2020) and pandemic (23 March, 2020 to 28 December, 2020) time periods for a Washington State cohort (N = 77,411 pregnancies)

| Demographics and outcomes | Prepandemic 1 January, 2016 to 23 February, 2020 N = 65,214 mean ± SD or n (%) |

Pandemic 23 March, 2020 to 28 December, 2020 N = 12,197 mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nulliparous | 26,631 (40.8) | 5256 (43.1) |

| Race and ethnicity of birthing women/person | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 34,515 (52.9) | 5967 (48.9) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2670 (4.1) | 512 (4.2) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 10,713 (16.4) | 2046 (16.8) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 13,060 (20.0) | 2548 (20.9) |

| American Indian or Native Alaskan | 696 (1.1) | 103 (0.8) |

| Other or mixed race | 1963 (3.0) | 372 (3.0) |

| Missing | 1597 (2.4) | 649 (5.3) |

| Rural zip code | 5310 (8.1) | 920 (7.5) |

| Missing rural indicator | 1649 (2.5) | 351 (2.9) |

| Medicaid insurance | 19,537 (30.0) | 3351 (27.5) |

| Missing insurance | 2313 (3.5) | 66 (0.5) |

| Distressed Communities Index | ||

| Prosperous | 29,543 (45.3) | 5576 (45.7) |

| Comfortable | 16,137 (24.7) | 3040 (24.9) |

| Mid-tier | 5931 (9.1) | 1155 (9.5) |

| At risk | 10,097 (15.5) | 1765 (14.5) |

| Distressed | 2839 (4.4) | 534 (4.4) |

| Missing | 667 (1.0) | 127 (1.0) |

| Age of birthing person (y) | 30.4 ± 5.4 | 30.8 ± 5.4 |

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 6.6 | 27.4 ± 6.7 |

| Pregestational BMI (kg/m2) categories | ||

| Underweight or normal weight (<24.9) | 30,128 (46.2) | 5454 (44.7) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 17,794 (27.3) | 3288 (27.0) |

| Obese class I (30.0–34.9) | 9362 (14.4) | 1809 (14.8) |

| Obese class II (35.0–39.9) | 4595 (7.0) | 935 (7.7) |

| Obese class III (≥40.0) | 3335 (5.1) | 711 (5.8) |

| Height of birthing person (cm) | 163.1 ± 7.2 | 163.0 ± 7.1 |

| Total pregnancy weight gain (kg) | 12.3 ± 6.1 | 12.4 ± 6.5 |

| Subgroup: pregestational BMI <24.9 | 13.8 ± 5.0 | 14.0 ± 5.2 |

| Subgroup: pregestational BMI 25 to <30 | 12.6 ± 5.9 | 12.8 ± 6.3 |

| Subgroup: pregestational BMI 30+ | 9.3 ± 6.9 | 9.4 ± 7.3 |

| Total pregnancy weight gain z-score | −0.1 ± 1.1 | −0.1 ± 1.2 |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 38.8 ± 1.7 | 38.7 ± 1.7 |

| Infant birthweight (g) | 3367.5 ± 538.3 | 3354.0 ± 533.4 |

Table 2.

Infant cohort demographic characteristics and outcomes by prepandemic (1 January, 2016 to 23 February, 2020) and pandemic (23 March, 2020 to 28 December, 2020) time periods for a Washington State cohort (N = 104,936 infants)

| Demographics and outcomes | Prepandemic 1 January, 2016 to February 23, 2020 N = 88,904 mean ± SD or n (%) |

Pandemic 23 March, 2020, to 28 December, 2020 N = 16,032 mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nulliparous pregnancy | 35,722 (40.2) | 6798 (42.4) |

| Race or ethnicity of birthing person/woman | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 46,023 (51.8) | 7571 (47.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4310 (4.8) | 754 (4.7) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 15,024 (16.9) | 2702 (16.9) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 17,017 (19.1) | 3058 (19.1) |

| American Indian or Native Alaskan | 1241 (1.4) | 197 (1.2) |

| Other or mixed race | 3113 (3.5) | 547 (3.4) |

| Missing | 2176 (2.4) | 1203 (7.5) |

| Rural zip code | 7306 (8.2) | 1285 (8.0) |

| Missing rural indicator | 2460 (2.8) | 480 (3.0) |

| Medicaid insurance | 30,921 (34.8) | 5169 (32.2) |

| Missing insurance | 2464 (2.8) | 89 (0.6) |

| Distressed Communities Index | ||

| Prosperous | 37,144 (41.8) | 6677 (41.6) |

| Comfortable | 22,308 (25.1) | 4106 (25.6) |

| Mid-tier | 8981 (10.1) | 1729 (10.8) |

| At risk | 14,906 (16.8) | 2548 (15.9) |

| Distressed | 4415 (5.0) | 767 (4.8) |

| Missing | 1150 (1.3) | 205 (1.3) |

| Age of birthing person (y) | 30.2 ± 5.6 | 30.5 ± 5.6 |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 38.7 ± 1.9 | 38.6 ± 1.8 |

| Infant birthweight (g) | 3342.2 ± 563.9 | 3332.0 ± 556.4 |

| Infant birthweight z-score | 0.1 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 1.0 |

Pregnancy weight gain and infant birthweight: prepandemic compared with postpandemic

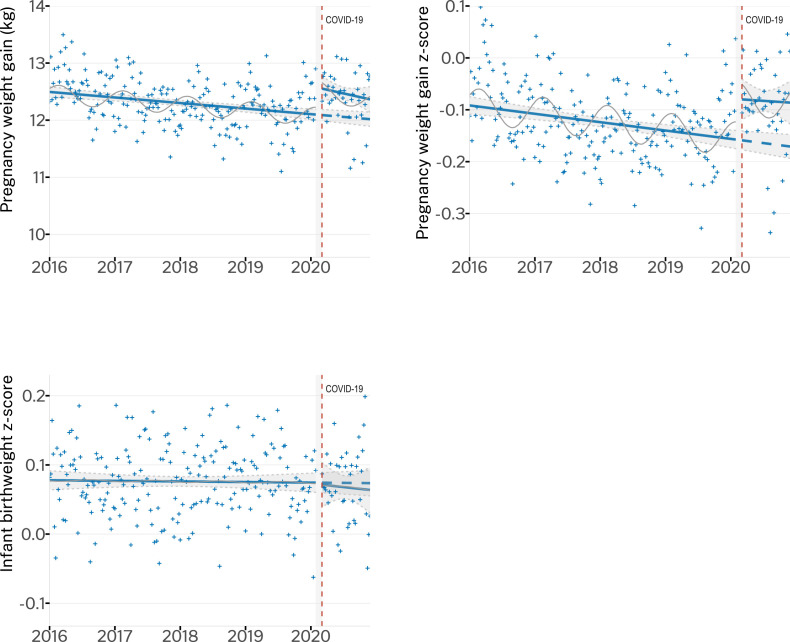

We compared the 40-wk postpandemic data (23 March, 2020, to 28 December, 2020) to the same period in 2019. From March to December 2019, the mean pregnancy weight gain was 12.13 kg (95% CI: 12.02, 12.24 kg) and the z-score was −0.14 (95% CI: −0.16, −0.12), compared with the mean pregnancy weight gain of 12.39 kg (95% CI: 12.28, 12.51 kg) and z-score of −0.092 (95% CI: −0.11, −0.07) in the postpandemic period (March to December 2020). The mean infant birthweight z-scores were unchanged (0.075; 95% CI: 0.063, 0.086) compared with the postpandemic period (0.068; 95% CI: 0.044, 0.091). Interrupted time series (Figure 2 , Supplemental Table 2) models showed decreasing yearly trend before the pandemic in both pregnancy weight gain (−0.12 kg/y; 95% CI: −0.21, −0.03 kg/y) and z-score (−0.016/y, 95% CI: −0.03, 0.00)/y), which represents ∼2% of the study population in 2019 having lower pregnancy weight gain than in 2016.

Figure 2.

Interrupted time series graphs for pregnancy weight gain, z-score, and infant birthweight z-score showing predicted trends and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic onset (23 March, 2020) in a Washington State cohort (1 January, 2016 to 28 December, 2020) (N = 77,411 pregnancies; N = 104,936 infants). Points (+) represent the mean outcome by study week; modeled (predicted) trend is a solid line; the counterfactual is a dashed line; the seasonal modeled effect is a solid thin line; 95% CI for modeled trends in light gray shading. Plotted trendlines are drawn based on models unadjusted by random effects.

Despite this yearly decrease in pregnancy weight gain, infant birthweight z-scores were stable (0.001/y; 95% CI: −0.01, 0.01/y). Our models estimated that at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the mean pregnancy weight gain increased (+0.49 kg; 95% CI: 0.25, 0.73 kg) and the pregnancy weight gain z-scores increased (+0.08; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.13); however, infant z-scores (−0.004; 95% CI: −0.04, 0.03) were unchanged. We found no statistically significant change in the yearly time trends in infant z-scores after the pandemic onset.

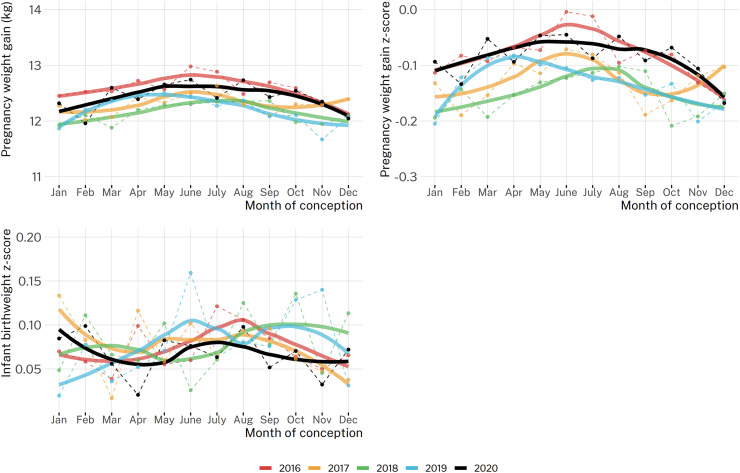

Seasonal effects

Seasonal plots (Figure 3 ) revealed higher pregnancy weight gain and pregnancy weight gain z-scores for pregnancies conceived in the late spring (May–June) than for those conceived in the late fall (November–December). The models estimated a seasonal trend where the difference from the maximum weight gain (births in the last week of February) to the minimum (births in the first week of September) was 0.32 kg (95% CI: 0.26, 0.38 kg) for weight gain, 0.066 (95% CI: 0.055, 0.078) for weight gain z-score (∼3 percentiles change), and nonsignificant (−0.002; 95% CI: −0.010, 0.007) for infant z-score.

Figure 3.

Average pregnancy weight gain, z-score, and infant birthweight z-score by month of conception across study years for a Washington State cohort (1 January, 2016 to 28 December, 2020) (N = 77,411 pregnancies; N = 104,936 infants).

Pregnancy weight gain at the 90th percentile of distribution

Examining the upper end of the weight gain distribution (90th percentile) identified an almost 3-fold increase in both pregnancy weight gain (1.20 kg; 95% CI: 0.75, 1.65 kg) and pregnancy weight gain z-scores (0.20; 95% CI: 0.12, 0.28) only, after the pandemic onset, compared with the population average models (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Quantile regression results for 90th percentiles using an interrupted time series analyses of the effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic onset in a Washington State cohort (1 January 1, 2016 to 28 December, 2020)

| Model terms | Quantile regression (90th percentile) estimate; 95% CI |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) (N = 77, 411) | |

| Level change | 1.20; 0.75, 1.65 |

| Trend change | −0.72; −1.72, 0.27 |

| Pregnancy weight gain z-score (N = 77,411) | |

| Level change | 0.20; 0.12, 0.28 |

| Trend change | −0.11; −0.28, 0.06 |

| Infant birthweight z-score (N = 104,936) | |

| Level change | −0.04; −0.10, 0.02 |

| Trend change | 0.07; −0.06, 0.20 |

Results stratified by pregestational BMI

Stratified results for pregnancy weight gain by pregestational BMI (<25: +0.42 kg; 25 to <30: +0.43; 30+: +0.49) were generally unchanged from the main results (+0.49 kg; 95% CI: 0.25, 0.73), although not statistically significant in the higher BMI categories, potentially because of the small sample size (Supplemental Figures 2–4, Supplemental Table 3). The results for z-scores and infant birthweight were also unchanged from the primary models. Stratified quantile regression results for the 90th percentiles of weight gain were also consistent across pregestational BMI categories (Supplemental Table 3). The mean weight gain decreased by pregestational BMI categories (postpandemic: 14.0 kg for <25 BMI and 9.4 kg for 30+ BMI) (Supplemental Table 4).

Increased duration of exposure to the pandemic

The overall results for all 3 outcomes were similar when excluding 9 or 15 weeks of births, although point estimates for the level change effect for weight gain and weight gain z-score moved away from the null (Supplemental Table 5). Additional sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Figures 5–9, Supplemental Results) did not alter the overall findings.

Discussion

Using rigorous analytic methods that control for underlying time trends, we found a modest (0.5 kg) increase in pregnancy weight gain and in pregnancy z-scores after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in a cohort of deliveries in Washington State. Pandemic-associated changes in pregnancy weight gain were more pronounced in people above the 90th percentile of weight gain. Despite pandemic-associated changes in pregnancy weight gain in this study group, and in subgroups, we found no pandemic-associated changes in infant birthweight z-scores at the population level. The results were consistent across the pregestational BMI categories.

The COVID-19 pandemic and changes in health services, policies, and governmental countermeasures have been linked to increases in stillbirth, maternal deaths, and maternal depression and a decrease in preterm births among high-income countries only [6]. Weight increases after the pandemic have been reported for nonpregnant study groups (adults and children) [4, 48]; however, research on this topic has focused on qualitative measures [49], short postpandemic time periods [23, 50], and “lockdowns” [49] and used “pre–post” designs [51]. Some countries reported fewer low birthweight infants after lockdown [52], but these results have not been confirmed in pooled meta-analyses [6, 53, 54]. Notably, 1 meta-analysis reported increased infant birthweights (mean: 17 g) after the pandemic [53].

Although our study found a statistically significant change, the magnitude of the mean increase in pregnancy weight gain (total of 0.5 kg or 1.1 lb per pregnancy) was relatively small. Our findings are of interest for several reasons. First, this modest increase in pregnancy weight gain could be part of the causal pathway for pandemic-associated decreases in low birthweight infants [6, 53] noted in other settings. Despite no apparent shift in mean infant birthweight z-scores in our cohort, it is possible that a modest increase in pregnancy weight gain contributed to decreases in low birthweight seen elsewhere. Second, increased pregnancy weight gain could alter the trajectory of weight gain throughout pregnancy. For example, a higher trajectory of first trimester pregnancy weight gain has been associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes [55]. Third, this modest change in weight gain impacts the entire population [56], which could shift a relatively large number of people toward “excess” weight gain and, thus, increase the rates of chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes [57]. For example, we noted a stronger pandemic impact (1.2 kg) for those who were already gaining “excess” pregnancy weight, which may further impact chronic health risks. Importantly, the magnitude of both pandemic-associated mean pregnancy weight gain (0.5 kg) and 90th percentile of weight gain (1.2 kg) was similar across all pregestational BMI categories. Therefore, pandemic-associated effects on weight gain may be most important for people with higher pregestational BMI, for whom a lower overall weight gain is recommended (5–9 kg) [23]. Nevertheless, our findings are also generally reassuring and suggest that the pandemic did not have a major impact on weight gain in pregnancy and/or that any effect was counteracted by decreases in commuting or other lifestyle changes [58].

We also found a seasonal effect in pregnancy weight gain, with 0.3 kg higher mean weight gain for pregnancies conceived in late winter than those conceived in early summer. This seasonal effect highlights the importance of controlling for seasonality in weight gain research [45]; otherwise, exposure-outcome or exposure-gestational age [59] relationships could be confounded by season—an issue that is critical when examining time-varying exposures, as in this study. Although seasonal trends in weight gain [44, 60] and infant birthweight [60] have most often been reported in countries where nutritional intake is correlated with the growing season, seasonal patterns also occurred in the United States [40, 60]. In our study, seasonal weight gain could be caused by changes in physical activity because of environmental factors; the fall–winter months in the Pacific Northwest are generally rainy and colder than summer months with moderate outdoor temperatures.

Our analysis did not identify any changes in infant birthweight z-scores, from either the pandemic or seasonality. It is possible that time-varying or neighborhood-level exposures (e.g., air pollution) attenuated the impact of weight gain on infant birthweight in our cohort [61, 62] or, more likely, that the small magnitudes of weight gain that we observed were not sufficient to meaningfully impact infant birthweights.

The strengths of this study include an interrupted time series analysis that controls for underlying time trends, adjustment for seasonality [45], a large sample size, and a longer postpandemic time period than many prior analyses. However, this study also had several limitations. First, we restricted to those with valid weight measurements in the first trimester and near to delivery. However, the proportion of excluded cases was consistent in the pre- and postpandemic time periods. We do not expect that the association between the pandemic and either weight gain or infant birthweight is different in those excluded or included in the study; thus, this should not lead to substantial bias in our primary findings. Second, we were unable to control for individual-level factors such as diet, exercise, employment, or stress. However, we see no indication that these factors would have changed in the population for reasons other than the pandemic onset, which means that our study appropriately characterized pandemic impacts on our outcomes. Last, our study population represents a single US state where pandemic-associated countermeasures were relatively widespread. This may impact generalizability to other US regions where there were relatively few countermeasures that restricted physical activity or movement.

Our study has implications for public health planning for future potential pandemic time periods where antenatal care and lifestyles are broadly disrupted. Virtual exercise programs [63] or fewer restrictions on the use of outdoor spaces (e.g., playgrounds and parks) with a low level of infection risk [64] could be 2 avenues to help promote physical activity and healthy pregnancies in any future pandemics. Although the weight gain effect overall was modest, individuals with higher pregestational BMI were equally impacted; therefore, public health efforts to promote healthy lifestyles after widespread disruptions such as the COVID-19 pandemic could be most relevant in this specific population.

Author contributions

EN, JAH, MRL, and PJ designed the research. EN performed the statistical analysis. EN, JAH, PJ, AK, and MRL wrote the article. EN had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

MRL has received consulting fees from Health Canada, ITAD, and the Conference Board of Canada and payment for expert testimony from the Attorney General of Canada and the Federation of Post-Secondary Educators.

Sources of support for the work

EN was supported by a Canadian Vanier Scholarship (2018–2021). This supporting source had no involvement or restrictions regarding the publication of this work. MRL and JAH received salary support from Canada Research Chair awards from the Canadian Federal Government. The Foundation for Health Care Quality (Obstetrical Care Outcomes Assessment Program) provided in-kind support for dataset creation.

Data Availability

The data described in the manuscript and code book are collected as part of a coordinated quality improvement program and are not publicly available.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2022.09.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Hale T., Angrist N., Goldszmidt R., Kira B., Petherick A., Phillips T., et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker) Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(4):529–538. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhutani S., Vandellen M.R., Cooper J.A. Longitudinal weight gain and related risk behaviors during the Covid-19 pandemic in adults in the us. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):1–14. doi: 10.3390/nu13020671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulugeta W., Desalegn H., Solomon S. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on weight status and factors associated with weight gain among adults in Massachusetts. Clin Obes. 2021;11(4) doi: 10.1111/cob.12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew H.S.J., Lopez V. Global impact of Covid-19 on weight and weight-related behaviors in the adult population: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1–32. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deschasaux-Tanguy M., Druesne-Pecollo N., Esseddik Y., de Edelenyi F.S., Allès B., Andreeva V.A., et al. Diet and physical activity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown (March-May 2020): results from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113(4):924–938. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chmielewska B., Barratt I., Townsend R., Kalafat E., van der Meulen J., Gurol-Urganci I., et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e759–e772. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brülhart M., Klotzbücher V., Lalive R., Reich S.K. Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature. 2021;600(7887):121–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04099-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green H., Fernandez R., MacPhail C. The social determinants of health and health outcomes among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Public Health Nurs. 2021;38(6):942–952. doi: 10.1111/phn.12959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bodnar L.M., Wisner K.L., Moses-Kolko E., Sit D.K.Y., Hanusa B.H. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the likelihood of major depressive disorder during pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(9):1290–1296. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molyneaux E., Poston L., Khondoker M., Howard L.M. Obesity, antenatal depression, diet and gestational weight gain in a population cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(5):899–907. doi: 10.1007/s00737-016-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Badon S.E., Hedderson M.M., Hyde R.J., Quesenberry C.P., Avalos L.A. Pre- and early pregnancy onset depression and subsequent rate of gestational weight gain. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(9):1237–1245. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridgland V.M.E., Moeck E.K., Green D.M., Swain T.L., Nayda D.M., Matson L.A., et al. Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS One. 2021;16(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapadia M.Z., Gaston A., Van Blyderveen S., Schmidt L., Beyene J., McDonald H., et al. Psychological antecedents of excess gestational weight gain: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0535-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onwuzurike C., Meadows A.R., Nour N.M. Examining inequities associated with changes in obstetric and gynecologic care delivery during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(1):37–41. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gundersen C., Hake M., Dewey A., Engelhard E. Food insecurity during COVID-19. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2021;43(1):153–161. doi: 10.1002/aepp.13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niles M.T., Bertmann F., Belarmino E.H., Wentworth T., Biehl E., Neff R. The early food insecurity impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2096–2097. doi: 10.3390/nu12072096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leddy A.M., Weiser S.D., Palar K., Seligman H. A conceptual model for understanding the rapid COVID-19-related increase in food insecurity and its impact on health and healthcare. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(5):1162–1169. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sartorelli D.S., Crivellenti L.C., Zuccolotto D.C.C., Franco L.J. Relationship between minimally and ultra-processed food intake during pregnancy with obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35(4) doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00049318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutcheon J.A., Stephansson O., Cnattingius S., Bodnar L.M., Johansson K. Is the association between pregnancy weight gain and fetal size causal?: a re-examination using a sibling comparison design. Epidemiology. 2019;30(2):234–242. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein R.F., Abell S.K., Ranasinha S., Misso M., Boyle J.A., Black M.H., et al. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2207–2225. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crane J.M.G., White J., Murphy P., Burrage L., Hutchens D. The effect of gestational weight gain by body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)34050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holowko N., Chaparro M.P., Nilsson K., Ivarsson A., Mishra G., Koupil I., et al. Social inequality in pre-pregnancy BMI and gestational weight gain in the first and second pregnancy among women in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(12):1154–1161. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kauffman E., Souter V.L., Katon J.G., Sitcov K. Cervical dilation on admission in term spontaneous labor and maternal and newborn outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):481–488. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos S., Eekhout I., Voerman E., Gaillard R., Barros H., Charles M.A., et al. Gestational weight gain charts for different body mass index groups for women in Europe, North America, and Oceania. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):201. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1189-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander G.R., Himes J.H., Kaufman R.B., Mor J., Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aris I.M., Kleinman K.P., Belfort M.B., Kaimal A., Oken E.A. 2017 US reference for singleton birth weight percentiles using obstetric estimates of gestation. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basso O., Wilcox A. Mortality risk among preterm babies: immaturity versus underlying pathology. Epidemiology. 2010;21(4):521–527. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181debe5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens A.J., Barton J.R., Bentum N.A.A., Blackwell S.C., Sibai B.M. General guidelines in the management of an obstetrical patient on the labor and delivery unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37(8):829–836. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheikh Ismail L., Bishop D.C., Pang R., Ohuma E.O., Kac G., Abrams B., et al. Gestational weight gain standards based on women enrolled in the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st project: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2016;352:i555. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rangel Bousquet Carrilho T.M., Rasmussen K., Rodrigues Farias D., Freitas Costa N.C., Araújo Batalha M., Reichenheim E.M., et al. Agreement between self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and measured first-trimester weight in Brazilian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):734. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duryea E.L., Hawkins J.S., McIntire D.D., Casey B.M., Leveno K.J. A revised birth weight reference for the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rural Urban Commuting Area Codes Data [Internet]. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; 2011 [cited 2022 Aug 14]. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-data.php.

- 34.Nethery E., Gordon W., Bovbjerg M.L., Cheyney M. Rural community birth: maternal and neonatal outcomes for planned community births among rural women in the United States, 2004-2009. Birth. 2018;45(2):120–129. doi: 10.1111/birt.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Economic Innovation Group . 2020. Distressed Communities [Internet]https://eig.org/distressed-communities/ [cited 2022 Aug 18]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kontopantelis E., Doran T., Springate D.A., Buchan I., Reeves D. Regression based quasi-experimental approach when randomisation is not an option: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:1–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernal J.L., Cummins S., Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herring S.J., Rose M.Z., Skouteris H., Oken E. Optimizing weight gain in pregnancy to prevent obesity in women and children. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(3):195–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson K., Linné Y., Rössner S., Neovius M. Maternal predictors of birthweight: the importance of weight gain during pregnancy. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2007;1(4):223–290. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Currie J., Schwandt H. Within-mother analysis of seasonal patterns in health at birth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(30):12265–12270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307582110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutcheon J.A., Moskosky S., Ananth C.V., Basso O., Briss P.A., Ferré C.D., et al. Good practices for the design, analysis, and interpretation of observational studies on birth spacing and perinatal health outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2019;33(1):O15–24. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hategeka C., Ruton H., Karamouzian M., Lynd L.D., Law M.R. Use of interrupted time series methods in the evaluation of health system quality improvement interventions: a methodological systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(10):1–13. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhaskaran K., Gasparrini A., Hajat S., Smeeth L., Armstrong B. Time series regression studies in environmental epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):1187–1195. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fahey C.A., Chevrier J., Crause M., Obida M., Bornman R., Eskenazi B. Seasonality of antenatal care attendance, maternal dietary intake, and fetal growth in the VHEMBE birth cohort, South Africa. PLoS One. 2019;14(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neophytou A.M., Kioumourtzoglou M.A., Goin D.E., Darwin K.C., Casey J.A. Educational note: addressing special cases of bias that frequently occur in perinatal epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(1):337–345. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2021. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koenker R., Hallock K.F. Quantile regression. J Econ Perspect. 2001;15(4):143–156. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin A.L., Vittinghoff E., Olgin J.E., Pletcher M.J., Marcus G.M. Body weight changes during pandemic-related shelter-in-place in a longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kirchengast S., Hartmann B. Pregnancy outcome during the first Covid 19 lockdown in Vienna, Austria. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J., Zhang Y., Huo S., Ma Y., Ke Y., Wang P., et al. Emotional eating in pregnant women during the Covid-19 pandemic and its association with dietary intake and gestational weight gain. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):1–12. doi: 10.3390/nu12082250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Du M., Yang J., Han N., Liu M., Liu J. Association between the COVID-19 pandemic and the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Philip R.K., Purtill H., Reidy E., Daly M., Imcha M., McGrath D., et al. Unprecedented reduction in births of very low birthweight (VLBW) and extremely low birthweight (ELBW) infants during the COVID-19 lockdown in Ireland: a “natural experiment” allowing analysis of data from the prior two decades. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J., D’Souza R., Kharrat A., Fell D.B., Snelgrove J.W., Murphy K.E., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and population-level pregnancy and neonatal outcomes: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(10):1756–1770. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaccaro C., Mahmoud F., Aboulatta L., Aloud B., Eltonsy S. The impact of COVID-19 first wave national lockdowns on perinatal outcomes: a rapid review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):676. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04156-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacDonald S.C., Bodnar L.M., Himes K.P., Hutcheon J.A. Patterns of gestational weight gain in early pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Epidemiology. 2017;28(3):419–427. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doyle Y.G., Furey A., Flowers J. Sick individuals and sick populations: 20 years later. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(5):396–398. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ukah U.V., Bayrampour H., Sabr Y., Razaz N., Chan W.S., Lim K.I., et al. Association between gestational weight gain and severe adverse birth outcomes in Washington State, US: a population-based retrospective cohort study, 2004-2013. PLoS Med. 2019;16(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Werf E.T., Busch M., Jong M.C., Hoenders H.J.R. Lifestyle changes during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1226. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11264-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darrow L.A., Strickland M.J., Klein M., Waller L.A., Flanders W.D., Correa A., et al. Seasonality of birth and implications for temporal studies of preterm birth. Epidemiology. 2009;20(5):699–706. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a66e96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chodick G., Flash S., Deoitch Y., Shalev V. Seasonality in birth weight: review of global patterns and potential causes. Hum Biol. 2009;81(4):463–477. doi: 10.3378/027.081.0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brauer M., Lencar C., Tamburic L., Koehoorn M., Demers P., Karr C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(5):680–686. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miranda M.L., Edwards S.E., Keating M.H., Paul C.J. Making the environmental justice grade: the relative burden of air pollution exposure in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(6):1755–1771. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8061755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silva-Jose C., Sánchez-Polán M., Diaz-Blanco Á, Coterón J., Barakat R., Refoyo I. Effectiveness of a virtual exercise program during COVID-19 confinement on blood pressure control in healthy pregnant women. Front Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.645136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cusack L., Sbihi H., Larkin A., Chow A., Brook J.R., Moraes T., et al. Residential green space and pathways to term birth weight in the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) study. Int J Health Geogr. 2018;17(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12942-018-0160-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data described in the manuscript and code book are collected as part of a coordinated quality improvement program and are not publicly available.