Resumo

Fundamento

A fibrilação atrial (FA) acomete cerca de 2% a 4% da população mundial. Nos pacientes internados em unidades de terapia intensiva, esta incidência pode chegar em até 23% naqueles com choque séptico. O impacto da FA nos pacientes sépticos se reflete em piores desfechos clínicos e o reconhecimento dos fatores desencadeantes pode ser alvo para estratégias de tratamento e prevenção futuras.

Objetivos

Verificar a relação entre desenvolvimento de FA e mortalidade nos pacientes acima de 80 anos incluídos no protocolo sepse e identificar fatores de risco que contribuam para o desenvolvimento de FA nesta população.

Métodos

Estudo observacional retrospectivo, com revisão de prontuários eletrônicos e inclusão de 895 pacientes com 80 anos ou mais, incluídos no protocolo sepse de um hospital privado de alta complexidade em São Paulo/SP, no período de janeiro de 2018 a dezembro de 2020. Todos os testes foram realizados com nível de significância de 5%.

Resultados

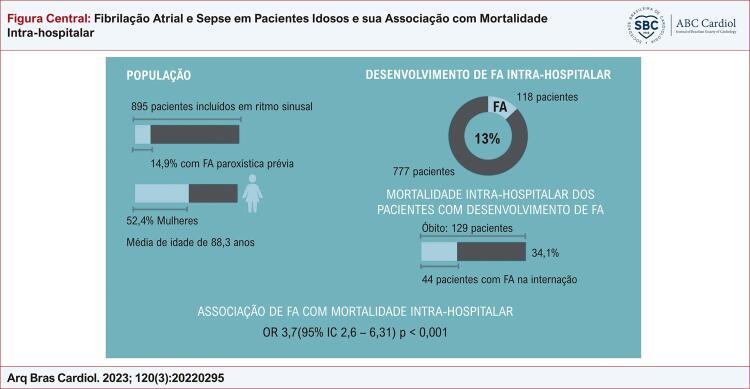

A incidência de FA na amostra foi de 13%. Após análise multivariada por regressão logística múltipla, foi possível demonstrar associação de mortalidade na população estudada, com o escore SOFA ( odds ratio [OR] 1,21 [1,09 – 1,35]), valores mais altos de proteína C-reativa (OR 1,04 [1,01 – 1,06]), necessidade de droga vasoativa (OR 2,4 [1,38 – 4,18]), uso de ventilação mecânica (OR 3,49 [1,82 – 6,71]) e principalmente FA (OR 3,7 [2,16 – 6,31).

Conclusões

No paciente grande idoso (80 anos ou mais) com sepse, o desenvolvimento de FA se mostrou como fator de risco independente para mortalidade intra-hospitalar.

Keywords: Arritmias Cardíacas, Fibrilação Atrial, Idoso, Sepse, Hospitalização, Mortalidade Hospitalar

Introdução

A fibrilação atrial (FA) é a arritmia cardíaca sustentada mais comum, acometendo cerca de 2% a 4% da população mundial, o que implica em grande morbimortalidade e altos custos para os serviços de saúde.1 , 2 Dentre os pacientes que necessitam de internação hospitalar por qualquer outro motivo, a FA segue como a arritmia cardíaca mais detectada, especialmente em pacientes críticos. O risco de desenvolvimento de FA em pacientes admitidos na unidade de terapia intensiva varia entre 4,5% e 11%, chegando até 23% naqueles com choque séptico.3 , 4

Dentre os vários fatores de risco estabelecidos para FA, talvez a idade seja o mais proeminente, e o aumento da longevidade da população deve produzir um crescente número de novos casos,1 , 2 o que torna os idosos, principalmente os grandes idosos (aqueles com idade acima de 80 anos), mais suscetíveis aos efeitos deletérios e riscos já conhecidos decorrentes da doença, agravados inclusive por outras comorbidades, frequentes nesta população, e sua potencial fragilidade.

Apesar de já existir uma relação bem estabelecida entre idade e FA,5 os mecanismos responsáveis pelo desenvolvimento da arritmia em pacientes críticos não são totalmente compreendidos. Provavelmente decorrem de um remodelamento atrial acelerado em combinação com fatores desencadeantes da arritmogênese, habitualmente encontrados em doentes mais graves,4 como inflamação, distúrbios hidroeletrolíticos e medicações pró-arrítmicas, dentre elas vasopressores e inotrópicos.6

O impacto da FA nesta população se reflete em piores desfechos clínicos, destacando-se por sua importância o aumento no tempo de internação hospitalar, o que infere inclusive em custos, aumento no tempo de ventilação mecânica e suas consequências, e maior mortalidade.7 - 10 Entretanto, a sua importância no ambiente crítico ainda não está totalmente clara, ora funcionando como um determinante da piora do paciente, ora como um marcador de gravidade de doenças de base, podendo ser utilizada inclusive como um fator prognóstico.3 , 6

Dentro ainda de várias incertezas existentes no ambiente crítico alusivas à FA, a relação entre a arritmia e sepse, principalmente em idosos, ainda suscita diversas teorias. Apesar de estudos crescentes sobre sepse na última década, poucos trabalhos abordaram sua relação com FA em uma população muito idosa (80 anos ou mais). Estes pacientes talvez sejam os mais beneficiados em se manter em ritmo sinusal ou terem a FA revertida o mais breve possível, visto que são habitualmente mais frágeis e têm menor reserva funcional.

Diante do que foi posto anteriormente, torna-se importante e extremamente relevante um estudo que aborde o tema, trazendo informações adicionais que possam contribuir com a literatura vigente. Baseado nisso, este trabalho tem como objetivo primário verificar a associação de mortalidade intra-hopitalar com o desenvolvimento de FA nos pacientes com sepse e, entre os objetivos secundários, identificar potenciais fatores de risco que contribuam para o desenvolvimento de FA nesta população e comparar o tempo de internação entre os pacientes que desenvolveram FA e aqueles que permaneceram em ritmo sinusal.

Métodos

Trata-se de um estudo observacional retrospectivo, com coleta de dados secundários a partir de prontuários eletrônicos revisados de pacientes com 80 anos ou mais, incluídos no protocolo sepse de um hospital privado de alta complexidade em São Paulo/SP, no período de janeiro de 2018 a dezembro de 2020. O Trabalho foi aprovado pelo Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital Sírio Libanês, Protocolo CAAE 47665721.9.0000.546.

Para definir FA, foram utilizados dados do ritmo cardíaco descritos nos prontuários e, quando disponíveis, registros de eletrocardiograma de 12 derivações anexados.

O protocolo sepse utilizado pelo serviço, o qual foi baseado na definição da diretriz da Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SEPSIS-3) de 2016,11 consistia em foco infeccioso possível ou provável associado a dois dos seguintes marcadores de síndrome da resposta inflamatória sistêmica: frequência cardíaca > 90 bpm, temperatura corporal > 38°C ou < 36°C, frequência respiratória > 20 irpm, leucócitos > 12.000/mm3 ou < 4000/mm3; ou pelo menos um marcador de disfunção orgânica, caracterizados por: lactato > 22 mg/dL, creatinina > 2,0 mg/dL, bilirrubina > 2,0 mg/dL, índice de normalização internacional > 1,5, tempo de tromboplastina ativada > 60 segundos ou plaquetas < 100.000/mm3.

Estavam aptos à inclusão 1339 prontuários e foram excluídos 444 que se apresentavam em arritmia à admissão ou eram portadores de marca-passo cardíaco. Restaram 895 pacientes admitidos em ritmo sinusal, dentre os quais, 14,9% já tinham apresentado FA paroxística previamente ( Figura 1 ).

Figura Central. : Fibrilação Atrial e Sepse em Pacientes Idosos e sua Associação com Mortalidade Intra-hospitalar.

Resumo dos principais resultados encontrados. FA: fibrilação atrial; IC: intervalo de confiança; OR: odds ratio.

As seguintes variáveis foram analisadas: sexo, idade, índice de massa corporal, tempo de internação hospitalar, mortalidade intra-hospitalar, comorbidades associadas (hipertensão arterial sistêmica, insuficiência cardíaca, diabetes mellitus, acidente vascular cerebral, doença arterial coronariana crônica, FA prévia, doença renal crônica dialítica, obesidade ou outras — demais comorbidades não citadas), uso de antiarrítmico prévio (amiodarona, betabloqueador e outros — bloqueador de canal de cálcio, digoxina, propafenona, etc.), dados ecocardiográficos como tamanho do átrio esquerdo e fração de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo (FEVE), foco da sepse (pulmonar, urinário, abdominal, cutâneo e outros — cateter, sistema nervoso central, etc.), escore SOFA (caracterizado pela soma de valores atribuídos de 0 a 4 a cada uma das seguintes variáveis: relação PaO2/FiO2, contagem plaquetária, valores de bilirrubinas totais, pressão arterial média, escala de coma de Glasgow, níveis de creatinina ou quantidade do débito urinário),11 valor de proteína C-reativa (PCR) na admissão, uso de drogas vasoativas (noradrenalina, vasopressina e/ou dobutamina) e necessidade de ventilação mecânica.

A definição de insuficiência cardíaca baseou-se nas comorbidades prévias descritas em prontuários e/ou nos exames de ecocardiografia prévios do paciente demonstrando FE < 40% (Simpsom ou Teicholz), valor que, de acordo com a Diretriz Brasileira de Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica e Aguda, a caracteriza como insuficiência cardíaca de fração de ejeção reduzida.12 Átrio esquerdo aumentado foi definido como a medida linear > 40 mm (valor de referência entre 28 e 40 mm). Resultados de PCR acima de 1 mg/dL, obtido pelo método imunoturbidimetria ultrassensível, devem ser interpretados como indicativos de possível processo infeccioso ou inflamatório.

Análise estatística

As características qualitativas foram descritas com o uso de frequências absolutas e relativas, baseadas no desenvolvimento de FA e foi verificada a associação das características com os grupos com uso de testes qui-quadrado ou testes exatos (teste exato de Fisher ou teste da razão de verossimilhanças).13 As características quantitativas foram descritas, segundo o desenvolvimento de FA, com uso de média e desvio padrão quando a distribuição dos dados foi normal ou mediana e quartis quando a distribuição dos dados não apresentou normalidade, sendo avaliada a normalidade com uso do teste Kolmogorov-Smirnov, e comparadas com uso do teste t-Student não pareado ou testes Mann-Whitney, respectivamente.

Foram estimados os odds ratios (OR) não ajustados para cada característica avaliada para o desfecho com uso de regressão logística bivariada e foi estimado o modelo de regressão logística múltipla, selecionando-se as variáveis que nos testes bivariados apresentaram níveis de significância inferiores a 0,20 (p < 0,20), sendo todas as variáveis inseridas no modelo, mantidas no modelo final ( full model ).

As análises foram realizadas com uso do software IBM-SPSS para Windows versão 22.0 e tabuladas com uso do software Microsoft-Excel 2010; os testes foram realizados com nível de significância de 5%.

Resultados

A média de idade da população estudada foi de 88,3 anos (± 5,3), sendo 52,4% mulheres. Durante a internação 118 pacientes evoluíram com FA, representando aproximadamente 13% do total de indivíduos acompanhados retrospectivamente ( Figura 1 ).

Como esperado, os pacientes que desenvolveram FA tinham uma frequência maior de insuficiência cardíaca e FA prévia em seu histórico, bem como um átrio esquerdo aumentado e FEVE reduzida no ecocardiograma.

Foi observado, entre os pacientes que evoluíram com FA, valores maiores do escore SOFA e níveis mais elevados de PCR.

Estes pacientes com arritmia permaneceram mais tempo internados, necessitaram mais frequentemente de drogas vasoativas e ventilação mecânica. Todos os dados acima encontram-se detalhados na Tabela 1 .

Tabela 1. – Descrição das características avaliadas segundo desenvolvimento de fibrilação atrial e resultado dos testes estatísticos.

| Variável | FA na internação | Total (N = 895) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Não (N = 777) | Sim (N = 118) | |||

| Idade, média ± DP | 88,2 ± 5,2 | 89,1 ± 5,6 | 88,3 ± 5,3 | 0,080** |

| Sexo, n (%) | 0,818 | |||

| Masculino | 371 (47,7) | 55 (46,6) | 426 (47,6) | |

| Feminino | 406 (52,3) | 63 (53,4) | 469 (52,4) | |

| IMC (Admissão), média ± DP | 25,3 ± 4,9 | 25,1 ± 4,8 | 25,3 ± 4,9 | 0,634** |

| Tempo de permanência (em dias), mediana (IIQ) | 10 (7; 16) | 13,5 (8; 25,3) | 10 (7; 17) | <0,001£ |

| HAS, n (%) | 0,145 | |||

| Não | 325 (41,8) | 41 (34,7) | 366 (40,9) | |

| Sim | 452 (58,2) | 77 (65,3) | 529 (59,1) | |

| DM, n (%) | 0,420 | |||

| Não | 523 (67,3) | 75 (63,6) | 598 (66,8) | |

| Sim | 254 (32,7) | 43 (36,4) | 297 (33,2) | |

| Insuficiência cardíaca, n (%) | 0,002 | |||

| Não | 634 (81,6) | 82 (69,5) | 716 (80) | |

| Sim | 143 (18,4) | 36 (30,5) | 179 (20) | |

| AVC, n (%) | 0,321 | |||

| Não | 665 (85,6) | 105 (89) | 770 (86) | |

| Sim | 112 (14,4) | 13 (11) | 125 (14) | |

| DAC crônica, n (%) | 0,647 | |||

| Não | 588 (75,7) | 87 (73,7) | 675 (75,4) | |

| Sim | 189 (24,3) | 31 (26,3) | 220 (24,6) | |

| FA, n (%) | <0,001 | |||

| Não | 688 (88,5) | 74 (62,7) | 762 (85,1) | |

| Sim | 89 (11,5) | 44 (37,3) | 133 (14,9) | |

| DRC não dialítica, n (%) | 0,739* | |||

| Não | 760 (97,8) | 115 (97,5) | 875 (97,8) | |

| Sim | 17 (2,2) | 3 (2,5) | 20 (2,2) | |

| Obesidade, n (%) | 0,969 | |||

| Não | 515 (66,3) | 78 (66,1) | 593 (66,3) | |

| Sim | 262 (33,7) | 40 (33,9) | 302 (33,7) | |

| Outras, n (%) a | 0,269* | |||

| Não | 24 (3,1) | 6 (5,1) | 30 (3,4) | |

| Sim | 753 (96,9) | 112 (94,9) | 865 (96,6) | |

| Foco da sepse, n (%) | 0,886# | |||

| Pulmonar | 436 (56,1) | 71 (60,2) | 507 (56,6) | |

| Urinária | 181 (23,3) | 23 (19,5) | 204 (22,8) | |

| Abdominal | 90 (11,6) | 13 (11) | 103 (11,5) | |

| Cutânea | 23 (3) | 3 (2,5) | 26 (2,9) | |

| Outras b | 47 (6) | 8 (6,8) | 55 (6,1) | |

| Antiarrítmico, n (%) | 0,053 | |||

| Não | 493 (63,4) | 63 (53,4) | 556 (62,1) | |

| Amiodarona | 91 (11,7) | 24 (20,3) | 115 (12,8) | |

| Betabloqueador | 149 (19,2) | 24 (20,3) | 173 (19,3) | |

| Outros c | 44 (5,7) | 7 (5,9) | 51 (5,7) | |

| AE (> 40 mm), n (%)& | 0,021 | |||

| Normal | 308 (46,7) | 38 (34,9) | 346 (45,1) | |

| Aumentado | 351 (53,3) | 71 (65,1) | 422 (54,9) | |

| FE (< 40% ), n (%)& | 0,040 | |||

| Normal | 621 (94,2) | 97 (89) | 718 (93,5) | |

| Diminuída | 38 (5,8) | 12 (11) | 50 (6,5) | |

| Escore SOFA na admissão, média ± DP | 3,2 ± 2,1 | 3,8 ± 2,6 | 3,3 ± 2,2 | 0,004** |

| PCR, mediana (IIQ) | 4,6 (1,4; 10,7) | 7,6 (2,2; 14) | 4,8 (1,4; 11,2) | 0,027£ |

| DVA, n (%) | <0,001 | |||

| Não | 615 (79,2) | 65 (55,1) | 680 (76) | |

| Sim | 162 (20,8) | 53 (44,9) | 215 (24) | |

| VM, n (%) | <0,001 | |||

| Não | 729 (93,8) | 90 (76,3) | 819 (91,5) | |

| Sim | 48 (6,2) | 28 (23,7) | 76 (8,5) | |

Teste qui-quadrado; * Teste exato de Fisher; # Teste da razão de verossimilhanças; ** Teste t-Student; £ Teste Mann-Whitney; & Nem todos possuem a informação. AE: átrio esquerdo; AVC: acidente vascular cerebral; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; DM: diabetes mellitus; DP: desvio padrão; DRC: doença renal crônica; DVA: droga vasoativa; FA: fibrilação atrial; FE: fração de ejeção; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica; IIQ: intervalo interquartil; IMC: índice de massa corpórea; PCR: proteína C-reativa; SOFA: Sequential Organ Faiulure Assessment; VM: ventilação mecânica. a Demais comorbidades não citadas. b Cateter, sistema nervoso central, etc. c Bloqueador de canal de cálcio, digoxina, propafenona, etc.

A taxa de mortalidade intra-hospitalar entre os pacientes que desenvolveram FA foi de 34,1% ( Figura 1 ). Estes pacientes permaneceram mais tempo internados, e os seguintes fatores contribuíram para o desfecho desfavorável, segundo análise estatística: comorbidades como insuficiência cardíaca prévia, o foco inicial da sepse, escore SOFA mais alto, valores mais elevados de PCR, necessidade de droga vasoativa, necessidade de ventilação mecânica e como suspeitado, o desenvolvimento de FA. Todos os dados acima encontram-se detalhados na Tabela 2 .

Tabela 2. – Descrição dos desfechos dos pacientes segundo as características avaliadas e resultado das análises não ajustadas.

| Variável | Status vital do paciente na alta | OR | IC (95%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vivo (N = 766) | Morto (N = 129) | Inferior | Superior | |||

| Idade, média ± DP | 88,3 ± 5,2 | 88,4 ± 5,6 | 1,00 | 0,97 | 1,04 | 0,815** |

| Sexo, n (%) | 0,909 | |||||

| Masculino | 364 (85,4) | 62 (14,6) | 1,00 | |||

| Feminino | 402 (85,7) | 67 (14,3) | 0,98 | 0,67 | 1,42 | |

| IMC (Admissão), média ± DP | 25,4 ± 4,8 | 24,8 ± 5,4 | 0,98 | 0,94 | 1,02 | 0,224** |

| Tempo de permanência (em dias), mediana (IIQ) | 10 (7; 16) | 13 (5; 29) | 1,01 | 1,01 | 1,02 | 0,027£ |

| HAS, n (%) | 0,664 | |||||

| Não | 311 (85) | 55 (15) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 455 (86) | 74 (14) | 0,92 | 0,63 | 1,34 | |

| DM, n (%) | 0,870 | |||||

| Não | 511 (85,5) | 87 (14,5) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 255 (85,9) | 42 (14,1) | 0,97 | 0,65 | 1,44 | |

| Insuficiência cardíaca, n (%) | 0,008 | |||||

| Não | 624 (87,2) | 92 (12,8) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 142 (79,3) | 37 (20,7) | 1,77 | 1,16 | 2,70 | |

| AVC, n (%) | 0,580 | |||||

| Não | 657 (85,3) | 113 (14,7) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 109 (87,2) | 16 (12,8) | 0,85 | 0,49 | 1,50 | |

| DAC crônica, n (%) | 0,298 | |||||

| Não | 573 (84,9) | 102 (15,1) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 193 (87,7) | 27 (12,3) | 0,79 | 0,50 | 1,24 | |

| FA, n (%) | 0,964 | |||||

| Não | 652 (85,6) | 110 (14,4) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 114 (85,7) | 19 (14,3) | 0,99 | 0,58 | 1,67 | |

| DRC não dialítica, n (%) | >0,999* | |||||

| Não | 749 (85,6) | 126 (14,4) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 17 (85) | 3 (15) | 1,05 | 0,30 | 3,63 | |

| Obesidade, n (%) | 0,915 | |||||

| Não | 507 (85,5) | 86 (14,5) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 259 (85,8) | 43 (14,2) | 0,98 | 0,66 | 1,45 | |

| Outras, n (%) a | 0,295* | |||||

| Não | 28 (93,3) | 2 (6,7) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 738 (85,3) | 127 (14,7) | 2,41 | 0,57 | 10,24 | |

| Foco da sepse, n (%) | 0,008# | |||||

| Pulmonar | 442 (87,2) | 65 (12,8) | 1,00 | |||

| Urinária | 182 (89,2) | 22 (10,8) | 0,82 | 0,49 | 1,37 | |

| Abdominal | 78 (75,7) | 25 (24,3) | 2,18 | 1,30 | 3,67 | |

| Cutânea | 22 (84,6) | 4 (15,4) | 1,24 | 0,41 | 3,70 | |

| Outras b | 42 (76,4) | 13 (23,6) | 2,11 | 1,07 | 4,13 | |

| Antiarrítmico, n (%) | 0,889 | |||||

| Não | 479 (86,2) | 77 (13,8) | 1,00 | |||

| Amiodarona | 96 (83,5) | 19 (16,5) | 1,23 | 0,71 | 2,13 | |

| Betabloqueador | 147 (85) | 26 (15) | 1,10 | 0,68 | 1,78 | |

| Outros c | 44 (86,3) | 7 (13,7) | 0,99 | 0,43 | 2,28 | |

| AE (> 40 mm), n (%) | 0,765 | |||||

| Normal | 295 (85,3) | 51 (14,7) | 1,00 | |||

| Aumentado | 363 (86) | 59 (14) | 0,94 | 0,63 | 1,41 | |

| FE (< 40%), n (%) | 0,015 | |||||

| Normal | 621 (86,5) | 97 (13,5) | 1,00 | |||

| Diminuída | 37 (74) | 13 (26) | 2,25 | 1,15 | 4,38 | |

| Escore SOFA na admissão, média ± DP | 3 ± 1,9 | 4,8 ± 2,9 | 1,40 | 1,29 | 1,52 | <0,001** |

| PCR, mediana (IIQ) | 4,4 (1,3; 10,6) | 8,1 (2,6; 17,9) | 1,05 | 1,03 | 1,07 | <0,001£ |

| DVA, n (%) | <0,001 | |||||

| Não | 626 (92,1) | 54 (7,9) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 140 (65,1) | 75 (34,9) | 6,21 | 4,18 | 9,22 | |

| VM, n (%) | <0,001 | |||||

| Não | 731 (89,3) | 88 (10,7) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 35 (46,1) | 41 (53,9) | 9,73 | 5,89 | 16,08 | |

| FA na internação, n (%) | <0,001 | |||||

| Não | 692 (89,1) | 85 (10,9) | 1,00 | |||

| Sim | 74 (62,7) | 44 (37,3) | 4,84 | 3,13 | 7,49 | |

Teste qui-quadrado; * Teste exato de Fisher; # Teste da razão de verossimilhanças; ** Teste t-Student; £ Teste Mann-Whitney. AE: átrio esquerdo; AVC: acidente vascular cerebral; DAC: doença arterial coronariana; DM: diabetes mellitus; DP: desvio padrão; DRC: doença renal crônica; DVA: droga vasoativa; FA: fibrilação atrial; FE: fração de ejeção; HAS: hipertensão arterial sistêmica; IC: intervalo de confiança; IIQ: intervalo interquartil; IMC: índice de massa corpórea; OR: odds ratio; PCR: proteína C-reativa; SOFA: Sequential Organ Faiulure Assessment; VM: ventilação mecânica. a Demais comorbidades não citadas. b Cateter, sistema nervoso central, etc. c Bloqueador de canal de cálcio, digoxina, propafenona, etc.

Após análise multivariada por regressão logística múltipla, foi possível demonstrar associação de mortalidade na população estudada com o escore SOFA, valores mais altos de PCR, necessidade de droga vasoativa, uso de ventilação mecânica e principalmente FA ( Tabela 3 ) ( Figura 1 ).

Tabela 3. – Resultado do modelo ajustado para explicar o óbito nos pacientes do protocolo sepse com 80 anos ou mais.

| Variável | OR | IC (95%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Inferior | Superior | |||

| Insuficiência cardíaca | 1,60 | 0,91 | 2,81 | 0,104 |

| Foco da sepse | ||||

| Pulmonar | 1,00 | |||

| Urinária | 1,26 | 0,68 | 2,34 | 0,457 |

| Abdominal | 1,50 | 0,74 | 3,05 | 0,263 |

| Cutânea | 0,78 | 0,16 | 3,75 | 0,752 |

| Outras a | 1,37 | 0,56 | 3,35 | 0,494 |

| FE (< 40%) - ECO | 1,09 | 0,47 | 2,55 | 0,844 |

| Escore SOFA na admissão | 1,21 | 1,09 | 1,35 | <0,001 |

| PCR | 1,04 | 1,01 | 1,06 | 0,007 |

| DVA | 2,40 | 1,38 | 4,18 | 0,002 |

| VM, n (%) | 3,49 | 1,82 | 6,71 | <0,001 |

| FA na internação, n (%) | 3,70 | 2,16 | 6,31 | <0,001 |

Regressão logística múltipla (full model). DVA: droga vasoativa; FA: fibrilação atrial; FE: fração de ejeção; IC: intervalo de confiança; OR: odds ratio; PCR: proteína C-reativa; SOFA Sequential Organ Faiulure Assessment; VM: ventilação mecânica. a Cateter, sistema nervoso central, etc.

Discussão

A incidência global de FA nova ou recorrente encontrada em nossa população, durante a internação, foi de 13,2%. O que se percebe na literatura é uma grande variabilidade de resultados, por exemplo, em uma metanálise conduzida por Kuipers et al.,14 a incidência de FA em pacientes com sepse, sepse grave e choque séptico foi respectivamente de 8%, 10% e 23%.15 , 16 No estudo de Walkey et al.,17 incluindo mais de 40 mil pacientes, mas apenas com sepse grave (classificação antiga), foi encontrada uma incidência de 5,9% de FA nova. Já em Meierhenrich et al.,9 foram selecionados apenas pacientes com choque séptico e foi encontrada uma incidência de 46% de FA nova, 10 vezes mais do que aqueles pacientes com sepse sem evolução para choque. Entretanto, mais recentemente, a metanálise conduzida por Corica et al.,18 demonstrou prevalência de FA nova em pacientes sépticos de 13,5%, semelhante à do presente estudo. Essa variabilidade pode ser explicada pelos inúmeros critérios de inclusão e diferentes populações abordadas. Este estudo, por sua vez, representa uma parcela muito específica da população idosa cuja incidência de FA é maior, além de não diferenciar aqueles com sepse e choque séptico.

Dentre os fatores de risco que contribuíram para o desenvolvimento de FA durante a internação, destacaram-se o histórico prévio de insuficiência cardíaca e FA e achados ecocardiográficos que caracterizavam aumento do átrio esquerdo e redução da FEVE. Diversos trabalhos que abordaram o tema também tiveram impressões semelhantes,4 , 6 , 15 mas há controvérsias. Salman et al.,19 analisando uma coorte prospectiva, não demonstraram relação entre a apresentação de FA e o tamanho do átrio esquerdo, apesar de associar a queda na FEVE com maior chance de evolução para arritmia. Já Shaver et al.,15 em direção oposta, conseguiram demonstrar associação com o tamanho do átrio esquerdo, mas não com a FEVE. Apesar de não ser alvo deste trabalho, ensaios laboratoriais com o peptídeo natriurético cerebral o colocam em posição de marcador independente no desenvolvimento de FA, como cita Augusto et al.,20 Isso mais uma vez corrobora que a insuficiência cardíaca é um preditor para o surgimento da arritmia tanto ambulatorialmente como no ambiente crítico.21 - 23

Também foi observado neste trabalho, entre os pacientes que evoluíram com FA, valores maiores do escore SOFA e níveis mais elevados de PCR. Hoje, o papel inflamatório gerado pela sepse tem significativa importância no desenvolvimento e manutenção da FA. Steinber et al.,24 destacam que o processo inflamatório predispõe ao estresse oxidativo, apoptose e fibrose, gerando um substrato importante para desencadear a arritmia. Outro agravante nesse contexto é o ambiente pró-trombótico produzido pela inflamação, capaz de induzir disfunção endotelial, ativação plaquetária e a cascata de coagulação. Ambos os efeitos podem ser responsáveis não só pelo início e manutenção da FA, mas também piorar os desfechos trombóticos associados à arritmia.24 Estes achados foram reforçados por Harada et al.,25 que também associaram maiores valores de PCR e escore SOFA ao desenvolvimento de FA, inclusive a mortalidade, após análise ajustada. Launey et al.,23 também encontraram valores maiores de escore de SOFA em pacientes que evoluíram com FA. Meierhenrich et al.,9 evidenciaram que pacientes que desenvolveram FA, sépticos ou não, apresentaram níveis mais altos de PCR antes do evento arrítmico. Chung et al.,26 também demonstraram associação entre valores elevados de PCR e ocorrência e manutenção da FA. Nestes casos, o PCR elevado aponta para um estado inflamatório que promove o desenvolvimento ou a persistência de FA.

Inicialmente, sepse de foco abdominal ou outro (não urinário, pulmonar ou cutâneo) foi associado a maior mortalidade, entretanto, na análise multivariada, não foi encontrada diferença estatística. Apesar de existirem dados que apontem maior incidência de FA com infecções do trato respiratório e foco urinário,10 , 14 , 16 , 23 em nosso estudo, não foi possível determinar a relação entre os sítios de infecção e a incidência de FA.

Além de permanecerem mais tempo internados neste estudo, pacientes que desenvolveram FA também necessitaram mais frequentemente de droga vasoativa e ventilação mecânica. O uso de ventilação mecânica já foi evidenciado como fator de risco para FA em diversos estudos,4 , 7 , 21 mas ainda não é um consenso.15 Em pacientes com sepse que evoluem para choque, a necessidade de droga vasoativa se torna imperativa pela falha na compensação entre a demanda e a oferta de oxigênio aos tecidos, portanto, por si só, já é um fator de pior prognóstico. Esta instabilidade pode resultar em FA assim como a própria arritmia gera necessidade de doses mais altas de vasopressores. Esta relação já foi reproduzida em alguns estudos.4 , 15 , 22

Diversos trabalhos anteriores falharam em encontrar uma associação direta de FA nova ou recorrente com o desfecho de morte durante a internação, mas os resultados encontrados aqui, sugerem que o desenvolvimento de FA em pacientes sépticos, nesta faixa etária, tem forte impacto sobre a mortalidade intra-hospitalar. Tal achado vai de encontro a outros trabalhos recentes, incluindo metanálises de pacientes críticos, com sepse e/ou choque séptico que desenvolveram FA nova, os quais exibiram resultados semelhantes.8 , 10 , 13 , 14

Houve sempre uma grande discussão se a FA tinha um papel a desempenhar na evolução ou desfecho da sepse, ou simplesmente refletia a severidade da doença, como um marcador de gravidade. Como outros trabalhos referidos anteriormente aqui, a FA representou sim uma disfunção orgânica que implicou em piora do desfecho clínico. Diante do que foi exposto, a abordagem adequada da arritmia deve ser elevada a outro patamar de importância no contexto da evolução deste grupo de pacientes, sendo necessário o desenvolvimento de estratégias adequadas de prevenção e tratamento, visando redução de danos.15 Especificamente sobre este tópico, já existem resultados que mostraram que a falha na manutenção do ritmo sinusal em pacientes com sepse foi associada a piores taxas de mortalidade em comparação com aqueles pacientes que obtiveram sucesso na reversão da FA.9 , 16

Este estudo possui algumas limitações, como a definição de FA, que foi baseada em registros clínicos em prontuários e, quando disponíveis, eletrocardiograma de 12 derivações. Isto deixa espaço para possíveis episódios de FA paroxística não diagnosticada ou registrada pelo médico responsável. Também foram incluídos pacientes com FA recorrente, mas isto não se mostrou como viés de amostragem com implicação nos desfechos. Tal fato já tinha sido abordado em trabalhos realizados por Arrigo et al.,3 e Shaver et al.,15 que evidenciaram maiores taxas de mortalidade em pacientes com FA nova, provavelmente por menor tolerância às alterações hemodinâmicas provocadas pela arritmia, diferente de pacientes com FA recorrente, melhor adaptados. Além disso, por se tratar de estudo retrospectivo baseado em coleta de dados de prontuários eletrônicos e, também, por não dispor da causa mortis definitiva dos pacientes que evoluíram a óbito, são necessários novos estudos para elucidação dos resultados obtidos.

Conclusão

No paciente grande idoso (80 anos ou mais) com sepse, o desenvolvimento de FA se mostrou como fator de risco independente para mortalidade intra-hospitalar. Devido às evidências, é cada vez mais urgente abordar este tema nesta população em que a FA incide e tem seu maior impacto. Estes talvez sejam os mais beneficiados ao se manterem no ritmo sinusal ou terem a FA revertida o mais breve possível, visto que são habitualmente mais frágeis e têm menor reserva funcional. Além disso, a identificação de fatores de risco associados à FA no contexto crítico pode servir para eventuais estratégias de controle para prevenção.

Vinculação acadêmica

Este artigo é parte de conclusão de curso de Michele Ouriques Honorato pelo Programa de residência médica – Hospital Sírio Libanês.

Fontes de financiamento: O presente estudo não teve fontes de financiamento externas.

Referências

- 1.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, m-Lundqvist CB, l et. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zimerman LI, Fenelon G, Martinelli M, Filho, Grupi C, Atié J, Lorga A, Filho, et al. Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. Diretrizes Brasileiras de Fibrilação Atrial. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009;92(6) Supl.1:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrigo M, Ishihara S, Feliot E, Rudiger A, Deye N, Cariou A, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients and its association with mortality: a report from the FROG-ICU study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;266:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedford J, Harford M, Petrinic T, Young JD, Watkinson PJ. Risk factors for new-onset atrial fibrillation on the general adult ICU: A systematic review. J Crit care. 2019;53:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosch NA, Cimini J, Walkey AJ. Atrial fibrillation in the ICU. Chest. 2018;154(6):1424–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernando SM, Mathew R, Hibbert B, Rochwerg B, Munshi L, Walkey AJ, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation and associated outcomes and resource use among critically ill adults—a multicenter retrospective cohort study. 15Crit Care. 2020;24(1) doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2730-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian S-A, Schorr C, Ferchau L, Jarbrink ME, Parrillo JE, Gerber DR. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of septic patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation. J Crit Care. 2008;23(4):532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kanjanahattakij N, Rattanawong P, Krishnamoorthy P, Horn B, Chongsathidkiet P, Garvia V, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation is associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Cardiol. 2018;74(2):1–8. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2018.1477035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meierhenrich R, Steinhilber E, Eggermann C, Weiss M, Voglic S, Bogelein D, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with septic shock: at prospective observational study. R108Crit Care. 2010;14(3) doi: 10.1186/cc9057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi S, Litt D, Narula N. New-onset atrial fibrillation in sepsis is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Neth Heart J. 2015;23(2):82–88. doi: 10.1007/s12471-014-0641-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodhes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohde LEP, Montera MW, Bocchi EA, Clausell NO, Albuquerque DC, Rassi S, et al. Diretriz Brasileira de Insuficiência Cardíaca Crônica e Aguda. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;111(3):436–539. doi: 10.5935/abc.20180190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Tiruvoipati R, Green C. Atrial fibrillation and mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective study. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(4):336–341. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuipers S, Klein Klouwenberg PM, Cremer OL. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes of new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients with sepsis: a systematic review. 688Critical Care. 2014;18(6) doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0688-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaver CM, Chen W, Janz DR, May AK, Darbar D, Bernard GR, et al. Atrial Fibrillation Is an Independent Predictor of Mortality in Critically Ill Patients. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(10):2104–2111. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu WC, Lin WY, Lin CS, Huang HB, Lin TZ, Cheng SM, et al. Prognostic impact of restored sinus rhythm in patients with sepsis and new-onset atrial fibrillation. 373Crit Care. 2016;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walkey AJ, Wiener RS, Ghobrial JM, Curtis LH, Benjamin EJ. Incident stroke and mortality associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306(20):2248–2254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corica B, Romiti GF, Basili S, Proietti M. Prevalence of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation and Associated Outcomes in Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 547J Pers Med. 2022;12(4) doi: 10.3390/jpm12040547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salman S, Bajwa A, Gajic O, Afessa B. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients with sepsis. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23(3):178–183. doi: 10.1177/0885066608315838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Augusto JB, Fernandes A, Freitas PT, Gil V, Morais C. Predictors of de novo atrial fibrillation in a non-cardiac intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(2):166–173. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20180022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, Jensen PN, Piccini JP, Sinner MF, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medcare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949–55.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss TJ, Calland JF, Enfield KB, Gomez-Manjarres DC, Ruminski C, DiMarco JP, et al. New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in the Critically Ill. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):790–797. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Launey Y, Lasocki S, Asehnoune K, Gaudriot B, Chassier C, Cinotti R, et al. Impact of low-dose hydrocortisone on the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with septic shock. J Intensive Care Med. 2019;34(3):238–244. doi: 10.1177/0885066617696847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg I, Brogi E, Pratali L, Trunfio D, Giuliano G, Bignami E, et al. Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Septic Shock: A One-Year Observational Pilot Study. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2019;47(3):213–219. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2019.44789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harada M, Van Wagoner DR, Nattel S. Role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology and management. Circ J. 2015;79(3):495–502. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, Wazni O, Kanderian A, Carnes CA, et al. C-reative protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104(24):2886–2891. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.101760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]