ABSTRACT

Mammalian orthoreovirus serotype 3 Dearing is an oncolytic virus currently undergoing multiple clinical trials as a potential cancer therapy. Previous clinical trials have emphasized the importance of prescreening patients for prognostic markers to improve therapeutic success. However, only generic cancer markers such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Hras, Kras, Nras, Braf, and p53 are currently utilized, with limited benefit in predicting therapeutic efficacy. This study aimed to investigate the role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling during reovirus infection. Using a panel of specific p38 MAPK inhibitors and an inactive inhibitor analogue, p38 MAPK signaling was found to be essential for establishment of reovirus infection by enhancing reovirus endocytosis, facilitating efficient reovirus uncoating at the endo-lysosomal stage, and augmenting postuncoating replication steps. Using a broad panel of human breast cancer cell lines, susceptibility to reovirus infection corresponded with virus binding and uncoating efficiency, which strongly correlated with status of the p38β isoform. Together, results suggest p38β isoform as a potential prognostic marker for early stages of reovirus infection that are crucial to successful reovirus infection.

IMPORTANCE The use of Pelareorep (mammalian orthoreovirus) as a therapy for metastatic breast cancer has shown promising results in recent clinical trials. However, the selection of prognostic markers to stratify patients has had limited success due to the fact that these markers are upstream receptors and signaling pathways that are present in a high percentage of cancers. This study demonstrates that the mechanism of action of p38 MAPK signaling plays a key role in establishment of reovirus infection at both early entry and late replication steps. Using a panel of breast cancer cell lines, we found that the expression levels of the MAPK11 (p38β) isoform are a strong determinant of reovirus uncoating and infection establishment. Our findings suggest that selecting prognostic markers that target key steps in reovirus replication may improve patient stratification during oncolytic reovirus therapy.

KEYWORDS: breast cancer, oncolytic viruses, p38 MAPK, prognostic indicators, reovirus, virus entry

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus) is a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus that is widespread in the environment and nonpathogenic in humans. Reovirus type 3 Dearing PL strain (T3DPL) (1) exhibits oncolytic properties and is undergoing clinical trials for breast cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, and multiple myeloma under its clinical name Pelareorep (2). In a randomized phase II trial of Pelareorep in metastatic breast cancer, the median overall survival was extended from 10.4 months to 17.4, with no significant increase in response rate (P = 0.87) or progression-free survival (P = 0.87) (3). In head and neck cancers, a phase III trial found that reovirus therapy provided no clinical benefit over standard of care (4). Retrospective analysis of the patient cohorts, however, suggested that overall survival statistics could be slightly improved by inclusion of signaling pathways that enhance reovirus replication in cancer cells as prognostic markers (namely, epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR], Hras, Kras, Nras, Braf, and/or p53 signaling pathways) (5–10). These findings implore a need to identify additional prognostic markers for outcomes of reovirus therapy. Moreover, since the current prognostic markers EGFR, Hras, Kras, Nras, and Braf are signaling hubs that drive hundreds of downstream signaling cascades, more-specialized pathways could serve as more-specific prognostic markers. Ideally, specialized signaling pathways that impinge on distinct stages of reovirus replication in cancer cells are identified and could be utilized as accurate prognostic markers. For reovirus to initiate an infection, several steps must be carried out: the virus must bind to the host cell, induce endocytosis, and traffic to the endo-lysosome, uncoat efficiently, initiate viral RNA transcription, and establish viral factories. Cell signaling pathways that directly influence each of these replication steps could be useful in identifying more precise prognostic markers for reovirus oncotherapy outcomes.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) stress signaling pathways become activated by exposure to viruses, growth factors, and cytokines, and they govern key cellular processes such as cell growth, apoptosis, differentiation, and inflammatory responses. These processes may be integral to successful virus establishment and spread. MAPK pathways are composed of three kinase families, namely, extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), and p38 MAPKs (11, 12). Previous studies found that inhibitors of p38 MAPK and ERK signaling suppressed reovirus infection in cancer cells, suggesting that these pathways promote reovirus oncolysis (13). Mechanistically, ERK was found to support reovirus spread in cancer cells by downregulating cellular interferon-mediated antiviral responses (10), but the molecular basis for reovirus-promoting effects of p38 MAPK signaling remains unknown.

In the context of cancer, p38 MAPK signaling is proposed to function as a dual regulator. In healthy tissues, p38 MAPK signaling maintains normal processes such as the cell cycle, differentiation, and apoptosis. Contrarily, p38 MAPK signaling in cancer functions to drive tumor progression by inducing processes such as migration, angiogenesis, and inflammation (11, 12). Additionally, p38 MAPK signaling has been linked to the replication of numerous viruses, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), influenza virus, and avian reovirus (14–17). Though the p38 MAPK signaling pathway is involved in virus replication in each case, the precise mechanisms of action are different: for HCV, p38 MAPK directly interacts with the virus, restricting assembly and replication, whereas for avian reovirus, p38 MAPK signaling facilitates entry and endocytosis (14, 17).

This study aimed to elucidate the role of p38 MAPK during reovirus infection, to decipher the associated mechanisms, and to evaluate the potential of utilizing p38 MAPK as a prognostic marker for reovirus oncolytic virotherapy. Using specific p38 MAPK inhibitors and inactive analogs, p38 signaling was found to be essential for early steps of reovirus infection important for productive intracellular replication. Specifically, endocytosis, trafficking to lysosomal compartments, and postuncoating were dependent on p38 signaling. Moreover, the specific p38β isoform correlated strongly with reovirus entry efficacy in a panel of breast cancer cell lines. Collectively, these findings demonstrate how p38 MAPK signaling influences reovirus infection of cancer cells, suggesting p38β as a potential prognostic marker.

RESULTS

p38 MAPK signaling is essential for reovirus to establish infection.

Previous studies found that p38 MAPK is induced during reovirus infection (10) and that a pharmacological inhibitor of p38 signaling decreased reovirus infection (13). To understand how p38 signaling promotes reovirus infection, it was important to next establish which stage(s) of reovirus replication depends on p38 signaling. The transformed and tumorigenic L929 cell line was used for analysis due to its high permissivity to reovirus infection and common use in reovirus studies. However, due to the possibility of functional impairment of signaling pathways in transformed cells, the conventional p38 MAPK signaling cascade was initially characterized in L929 cells. To characterize the p38 MAPK signaling cascade, L929 cells were treated with anisomycin, a common activator of p38 MAPK signaling. Western blot analysis was performed for phosphor-p38 (P-p38), its upstream kinase MKK3/6, and well-established downstream targets of p38: phosphor-MSK1, phosphor-MNK1, phosphor-eEF2, and phosphor-ATF2 (Fig. 1A). Anisomycin treatment was associated with increased P-MKK3/6 and P-p38, as well as the direct p38 target MSK1 (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that p38 MAPK signaling is intact in L929 cells.

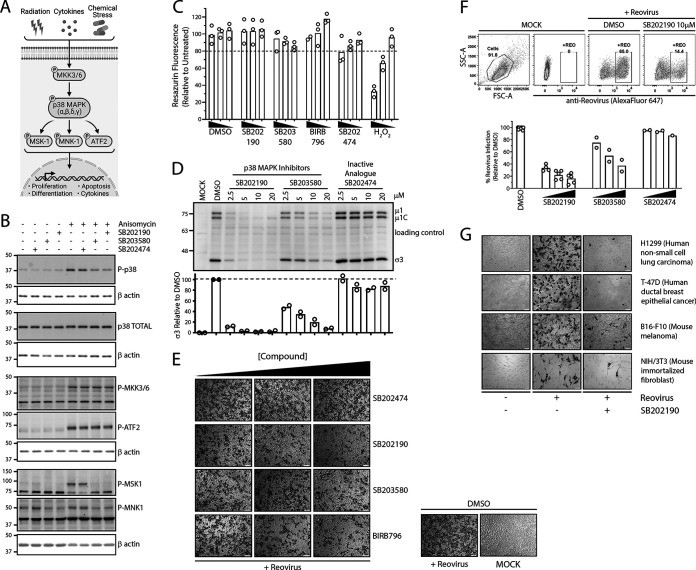

FIG 1.

p38 MAPK signaling promotes establishment of reovirus infection. (A) Summary of p38 MAPK activation and downstream signaling. (B) L929 cells were treated with 10 μM p38 MAPK inhibitors (SB202190 and SB203580) or inactive analogue (SB202474) for 1 h, followed by treatment with 500 nM p38 MAPK activator (anisomycin) for 30 min. Prototypic proteins of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway (A) were assessed using Western blot analysis. (C) L929 cells were treated with SB202190, SB203580, SB202474, or BIRB-796 at 20 μM, 10 μM, or 5 μM and respective DMSO for 12 h, followed by a medium change and additional incubation for 12 h. Cells were incubated in the presence of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 5 mM, 1 mM, or 0.2 mM) for 24 h without a 12-h medium change. Cell viability was assessed using resazurin fluorescence (n = 3 independent experiments). (D to G) Cells were treated with indicated compound dilutions for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then prechilled at 4°C for 1 h, followed by reovirus (MOI, 3) addition and incubation at 4°C for 1 h. Following extensive washing to remove unbound virus, medium was replenished with the indicated compound dilutions and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. (D) L929 cell lysates were assessed for reovirus proteins using Western blot analysis, representative image of 2 independent experiments. A background nonspecific band was used as a loading control. (E and F) L929 cells were fixed at 12 hpi, and virus-infected cells were stained using reovirus-specific antibodies, followed by either processing for immunohistochemistry using BCIP/NBT substrate, representative of 3 independent experiments (E), or flow cytometric analysis using Alexa Fluor 647 secondary antibodies, with 2 to 5 independent experiments depending on the inhibitor (F). (G) Similar to panel E, except that a panel of cell lines was used and SB202190 was used at 10 μM. Image is representative of 3 independent experiments. H1299 (MOI, 1), T-47D (MOI, 1), B16-F10 (MOI, 3), and NIH 3T3 (MOI, 20) cells were used.

To assess the impact and specificity of p38 inhibitors, anisomycin-treated cells were subsequently treated with a p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB202190, SB203580, or BIRB-796) or an inactive analogue (SB202474). SB202190 and SB203580 directly bind to the ATP binding site of p38 MAPK, while BIRB-796 binds to an allosteric site and induces indirect conformational restriction (18). To exclude off-target effects, SB202474, a chemically similar analogue of SB202190, was employed as a control due to its inability to interact with the p38 MAPK active site (19). Since the p38 MAPK signaling pathway is essential for cell survival, long-term experiments such as knockdown or knockout strategies were avoided (20, 21). In cells treated with anisomycin and p38 MAPK inhibitors, P-MKK3/6 increased to an extent similar to that under anisomycin-alone conditions (Fig. 1B); this supported the notion that p38 inhibitors did not disrupt signaling upstream of p38 MAPK. Although p38 MAPK inhibitors SB202190 and SB203580 decreased levels of P-p38 following anisomycin treatment, they did not fully eliminate p38 phosphorylation; this is typical among many other studies (22–27) and is caused by continued phosphorylation of p38 MAPK by upstream kinase MKK3/6 (22, 23). In other words, the inhibitors bind to the ATP binding active site of p38 and thereby stop phosphorylation of downstream targets such as MSK1 and MNK1, but they do not stop phosphorylation of p38 by upstream MKKs. Importantly, samples treated with p38 MAPK inhibitors in the presence of anisomycin resulted in decreased P-MNK1 and P-MSK1, corroborating inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling. The samples treated with the inactive analogue (SB202474) did not disrupt p38 MAPK signaling targets, supporting its use as an off-target control.

Pharmacological treatments can sometimes cause toxicity to cells that produce confounding effects. Therefore, the toxicities of p38 MAPK inhibitors were assessed at compound concentrations and treatment durations used in subsequent assays. L929 cells were treated with various concentrations of p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB202190), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a positive control for 12 h, followed by removal of the drug/DMSO and further incubation for an additional 12 h. These conditions exceeded the planned treatment duration of upcoming assays and were intended to detect any confounding effects. Cell viability was measured using a resazurin fluorescence dye as an indirect measurement of cellular metabolism. At all concentrations of SB202190 tested, no significant (>20%) toxicity was observed (Fig. 1C). Hydrogen peroxide treatment demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability with increasing concentration, confirming functionality of the resazurin assay. At all tested concentrations (5 to 40 μM) of SB202190 and DMSO, minimal cellular toxicity was observed, suggesting the safe use of 10 to 20 μM SB202190 in the L929 cell line model at equivalent treatment durations.

Having validated functional p38 MAPK signaling in L929 cells and the specificity and nontoxicity of p38 MAPK inhibitors, these inhibitors were applied to evaluate the role of p38 MAPK in the context of reovirus infection. Cells were pretreated with various concentrations of p38 MAPK inhibitors or the inactive analogue for 1 h prior to addition of reovirus and subsequently postinfection. Cell lysates were collected at 12 h postinfection (hpi) and subjected to Western blot analysis for reovirus protein expression. Reovirus structural proteins μ1C and σ3 were markedly reduced following p38 MAPK inhibitor treatments relative to those in untreated and inactive-analogue-treated cells (Fig. 1D). SB202190 and SB203580 reduced viral protein expression (μ1C and σ3) in a dose-dependent manner, with SB202190 being the more potent inhibitor at equivalent concentrations. Treatment with inactive analogue SB202474 minimally affected viral protein expression (μ1C and σ3). These results suggested that the benefits of p38 MAPK signaling for reovirus infection were achieved within the initial 12 h of the reovirus replication cycle.

The reduced levels of reovirus proteins following p38 MAPK inhibitor treatment suggested two possibilities: (i) that the proportion of cells that became productively infected by reovirus was reduced and/or (ii) that similar proportions of cells were productively infected but less virus replication occurred per productively infected cell. To distinguish between these possibilities, the effect of p38 MAPK inhibitors on the proportion of reovirus-infected cells was evaluated. L929 cells were exposed to reovirus for 1 h and supplemented with media containing p38 MAPK inhibitors at various doses for 12 h. Samples were fixed and reovirus-infected cells were visualized using immunocytochemistry. Both p38 MAPK inhibitors SB202190 and SB203580 reduced the proportion of cells positive for reovirus infection in a dose-dependent manner, with SB202190 exhibiting the most potent effects (Fig. 1E). Treatment with the inactive p38 MAPK inhibitor analogue (SB202474) did not reduce the number of cells positive for productive reovirus infection, suggesting that off-target effects of SB203580 and SB202190 are not likely responsible for reovirus inhibition (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, a clinically relevant p38 MAPK inhibitor, BIRB-796, also inhibited the number of cells productively infected by reovirus (Fig. 1E). The presence of fewer reovirus-positive cells following p38 inhibitor treatments was also confirmed by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 1F). Altogether, there was a clear reduction in the number of cells that became productively infected by reovirus when p38 MAPK was inhibited.

Finally, to establish whether p38 MAPK signaling was an essential pathway for reovirus infection in general rather than an L929-cell type dependent effect, reovirus infectivity was evaluated following SB202190 p38 MAPK inhibitor treatment in mouse B16-F10 melanoma cells, human H1299 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells, human T-47D breast ductal carcinoma cells, and mouse NIH 3T3 nontransformed fibroblasts. In all four cell lines tested, p38 MAPK inhibition drastically reduced the number of cells that became productively infected by reovirus (Fig. 1G). Therefore, the p38 MAPK signaling pathway is important for establishment of initial reovirus infection, irrespective of cell type and transformation status.

p38 MAPK signaling does not alter reovirus binding but expedites efficient viral entry.

p38 MAPK signaling is important for numerous cellular processes, such as endocytosis and endosomal trafficking, and therefore, treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitors prior to reovirus infection could potentially affect receptor expression on the cell surface and thereby reduce attachment of reovirus to cells. To evaluate if p38 MAPK signaling affects cell attachment of reovirus, L929 cells were pretreated for 1 h with a p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB202190) or activator (anisomycin) or left untreated, followed by reovirus adsorption at 4°C to permit attachment without entry. Unbound reovirus particles were removed by repeated rinsing, and cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for reovirus outer capsid proteins μ1C and σ3 to measure cell-bound virus and β-actin as a loading control. At both virus doses used, levels of cell-associated virus were unchanged between untreated and SB202190- or anisomycin-treated samples (Fig. 2A). As an alternative approach, attachment of 35S-radiolabeled reovirus to L929 cells pretreated with SB202190 was measured by liquid scintillation counting of total cell lysates. At all three reovirus dilutions tested, SB202190 treatment did not affect reovirus attachment (Fig. 2B). Therefore, reduction in the proportion of cells productively infected by reovirus following inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling is unlikely attributable to diminished reovirus-cell binding.

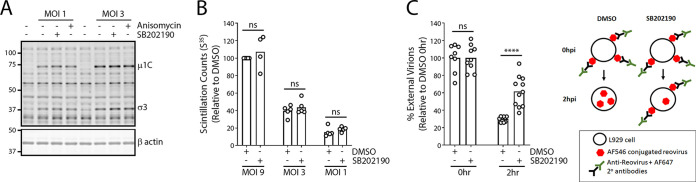

FIG 2.

Reovirus entry but not binding is attenuated upon inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling. (A) L929 cells were treated with the indicated compounds (SB202190, 10 μM; anisomycin, 500 nM) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then prechilled at 4°C for 1 h, followed by reovirus (MOI, 1 or 3) addition and incubation at 4°C for 1 h. Following extensive washing to remove unbound virus, cell lysates were collected and assessed for reovirus proteins using Western blot analysis. Western blots are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Cells were treated similarly to those for panel A, except that 35S-radiolabeled reovirus (MOI, 1, 3, or 9) was used, and cell lysates were collected and run on a scintillation counter. Each point on the bar graphs represents an independent experiment. (C) (Left) Cells were treated similarly to those for panel A, except that Alexa Fluor 546-labeled reovirus was used at an MOI of 20. Cells were fixed at 0 h immediately after binding or after 2 h of incubation at 37°C. External virions were stained using reovirus-specific antibodies without cell permeabilization. Cells were imaged using confocal microscopy, and external (Alexa Fluor 647) and total (Alexa Fluor 546) virions were quantified using the spot identification tool on Harmony high-content imaging and analysis software. Each point on the bar graph represents an individual cell, pooled from 2 independent experiments. ****, P < 0.0001; ns, not significant (P > 0.05) (unpaired t test). (Right) Diagrammatical depiction of the external and internal virion staining strategy.

Previous studies found that entry of avian reovirus via dynamin- and caveolin-mediated endocytosis is p38 MAPK dependent (17). Since mammalian reovirus also utilizes these endocytosis pathways, we assessed whether reovirus entry also depends on p38 MAPK signaling. To quantitatively measure endocytosis, reovirus particles were covalently conjugated to Alexa Fluor 546 (AF546) before addition to cells. Preconjugation of virus particles permitted quantification of both cell surface and internalized reovirus particles. To measure the percentage of virus particles that were not internalized after attachment to cells, extracellular virions were labeled on live cells using anti-reovirus antibodies and respective secondary antibodies conjugated to AF647 immediately prior to fixation. The percentage of external virions (AF647 positive) out of total (AF546 positive) became a reflection of endocytosis. To measure the effects of p38 MAPK signaling on virus particle endocytosis, cells were pretreated with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 for 1 h prior to exposure to AF546-conjugated reovirus at 4°C for 1 h to permit virus binding. Samples were processed immediately after binding (0 hpi) or following 2 h of incubation at 37°C to permit endocytosis. Extracellular virions were then labeled using primary anti-reovirus and AF647-conjugated secondary antibodies (Fig. 2C, left). Stained samples were fixed and imaged using confocal microscopy. At 0 hpi, as expected, the average number of virus particles on the surface of cells was similar between SB202190- and DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 2C). Conversely, at 2 hpi, SB202190-treated samples had an average of 30% virion internalization, while untreated samples had an average of 62% virion internalization, suggesting that p38 MAPK signaling promotes efficient endocytosis of reovirus.

Reovirus endosomal trafficking is facilitated by p38 MAPK signaling.

Treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 reduced the number of reovirus-infected cells ~9-fold (Fig. 1E and F) yet brought only a 2-fold reduction in virus internalization (Fig. 2C); this suggested that one or more steps downstream of endocytosis were also inhibited during SB202190 treatment. While monitoring AF546-conjugated reovirus that entered cells by 1 hpi, we consistently observed that SB202190-treated samples had distinctly larger “clusters” of internalized virions during p38 inhibition than did untreated samples (Fig. 3A, see arrows in bottom rightmost inset representing AF549 total virions at 1 hpi in SB202190-treated samples). The large clusters of incoming virions suggested a potential defect in endosomal trafficking.

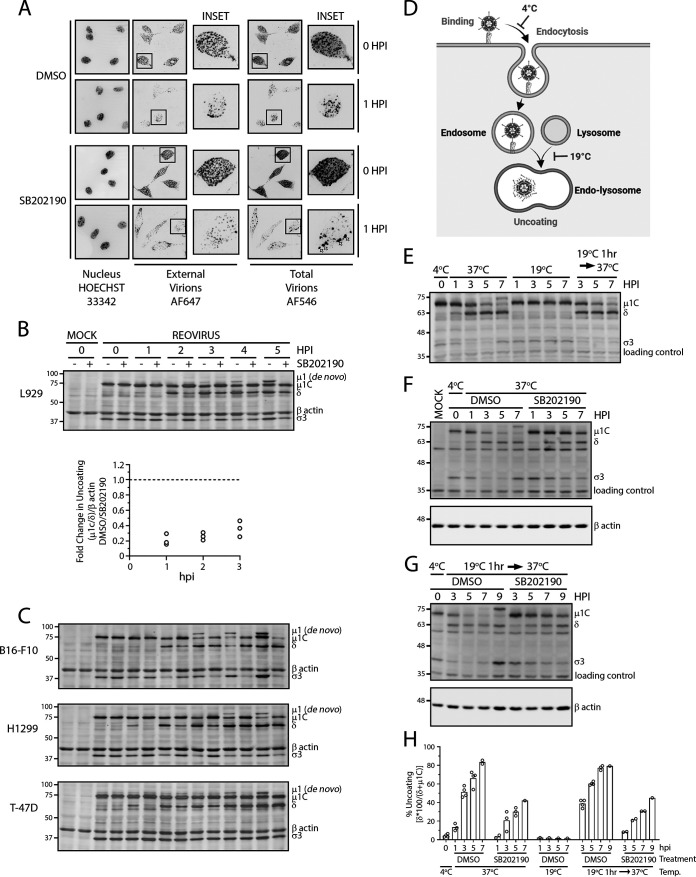

FIG 3.

Reovirus uncoating is mediated by p38 MAPK signaling. (A to C) Cells were treated with indicated compounds for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were then prechilled at 4°C for 1 h, followed by reovirus addition and incubation at 4°C for 1 h. Following extensive washing to remove unbound virus, medium was replenished with the indicated compounds and incubated at 37°C. (A) L929 cells were infected with Alexa Fluor 546-labeled reovirus (MOI, 20) and fixed at the indicated time points, followed by staining of external virions using reovirus-specific antibodies and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibodies. Nuclei were labeled using Hoechst 33342. Cells were imaged using confocal microscopy. Microscopy images are representative of 2 independent experiments. White arrows indicate aggregated virus compartments. (B) (Top) At the indicated time points, cell lysates were collected and assessed for reovirus proteins using Western blot analysis to monitor outer capsid uncoating. (Bottom) Quantification of capsid uncoating [(μ1C/δ)/β-actin], with each point representing an independent experiment (n = 3 total). (C) Similar to panel B but on the indicated cancer cell lines. Representative blots for 2 experiments for H1299 cells and a single experiment for T-47D and B16-F10 cells are shown. An MOI of 3 was used for all cell lines. (D) Summary of temperature effects on key steps of endosomal trafficking based on previous studies referenced in the text. (E to G) Reovirus (MOI, 3) was bound to L929 cells at 4°C cells similarly to what is shown in panel A, and cells were incubated at indicated temperature in the presence or absence of SB202190 at 10 μM. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated time points, and Western blot analysis for reovirus proteins was performed. (H) Quantification summary of capsid uncoating [(δ × 100/(δ + μ1C)] from Western blot analysis in panels E to G. Each circle represents an independent experiment (n = 2 to 5).

Reovirions are composed of two capsid shells: a core capsid that surrounds the dsRNA segmented genome and an outer capsid composed of the μ1 intermediate protein, the σ3 outermost layer, and the σ1 cell attachment proteins. To initiate infection, the outer capsid protein σ3 must be proteolytically degraded and the underlying μ1 must be cleaved into a hydrophobic δ fragment to generate intermediate subviral particles (ISVPs). ISVPs penetrate cellular membranes and deliver core particles to the cytoplasm. During infection of cancer cells, the essential process of outer capsid disassembly, or uncoating, requires lysosomal proteases. Accordingly, reovirus-containing endocytic compartments must adjoin with lysosomes to proteolytically generate ISVPs that penetrate endo-lysosomal membranes (28). If p38 signaling affects the fate of endocytic compartments containing reovirus, then reovirus uncoating should be affected by p38 MAPK inhibitors. To test this hypothesis, reovirus outer capsid disassembly was monitored in L929 cells in the presence or absence of p38 inhibition, using Western blot analysis to detect degradation of σ3 and cleavage of μ1C to δ as hallmarks of uncoating. At 0 hpi, equivalent viral capsid proteins were observed between untreated and SB202190-treated samples (Fig. 3B), validating that SB202190 does not alter virus-cell attachment (Fig. 2A and B). Conversely, μ1C-to-δ cleavage was delayed in SB202190-treated samples relative to that in untreated samples (Fig. 3B), indicating a delay in uncoating during p38 MAPK inhibition. Additionally, using de novo μ1 as an indication of new viral protein synthesis, untreated samples had detectable de novo μ1 as early as 3 hpi, while no detectable de novo μ1 was observed in SB202190-treated samples as late as 5 hpi. Similar trends were observed in mouse melanoma B16-F10 cells, human H1299 lung cancer cells, and T-47D breast cancer cells (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that p38 MAPK inhibition had similar effects on reovirus infection in different cancer cell lines. Therefore, p38 MAPK signaling is necessary for efficient reovirus uncoating, resulting in earlier initiation of viral protein synthesis.

That incoming reovirus particles were aggregating in large spots (Fig. 3A) and undergoing notably less uncoating (Fig. 3B) during p38 MAPK inhibition suggested that there may be altered trafficking of reovirus-containing endosomes. Early endosomes (pH 6.0 to 6.5) transition to late endosomes (pH 5.0 to 5.5) by means of a pH change mediated by the membrane-traversing vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase). Fusion of protease-containing lysosome vesicles facilitates the progression of the late endosome to an endo-lysosome (pH 4.5 to 5.0). Many previous studies in the context of both vesicular transport and rhinovirus entry have established that in cells incubated at a low temperature (18 to 20°C), endocytosis and subsequent transition to late endosomes occur normally, but endo-lysosome formation is inhibited due to vesicle fusion inhibition (29–38). To determine whether p38 MAPK signaling is important for endosome trafficking and/or lysosome fusion, we optimized the low-temperature approach to trap incoming virions in late endosomes and thereby were able to assess if p38 inhibitor activities occurred before or after trafficking to late endosome (Fig. 3D). To establish that 19°C incubation effectively prevents endo-lysosome formation and blocks reovirus uncoating, reovirus particles were bound to L929 cells at 4°C, and then reovirus uncoating at either 19°C or 37°C was monitored over 7 h. At 37°C, reovirus uncoating proceeded with σ3 degradation and μ1C-to-δ cleavage (Fig. 3E). However, at 19°C, σ3 degradation and μ1C cleavage were inhibited. Importantly, when cells were first incubated at 19°C for 1 h and then transitioned to 37°C, reovirus uncoating progressed; this indicated that the temperature-dependent block in reovirus uncoating was reversible. In other words, 19°C incubation blocked reovirus uncoating by trapping virions in late endosomes incapable of accessing lysosomal proteases, but resumption of endo-lysosome fusion by transition to 37°C restored reovirus uncoating. These results indicated that 19°C treatment did not aberrantly redirect endosomes to an alternative fate but rather “trapped” them in endosomes capable of resuming normal trafficking when temperatures rose. Moreover, similar uncoating kinetics were seen between infected cells that were incubated for 1 h at 19°C followed by 2 h at 37°C versus 37°C for the full 3 h, suggesting that reovirus particles were progressing at similar rates toward the endo-lysosomes.

The ability to trap virions in uncoating-incapable late endosomes enabled assessment of the effects of p38 MAPK inhibition on late progression from endosomes to endo-lysosomes independent of preceding endosome trafficking steps. If p38 MAPK signaling supports reovirus entry by mediating endosome-lysosome fusion as opposed to earlier stages of endosome trafficking, then addition of a p38 MAPK inhibitor after admission of reovirus into late endosomes at 19°C should still delay uncoating. To test this hypothesis, reovirus bound to L929 cells at 4°C either was treated immediately with p38 inhibitors and incubated at 37°C or was first incubated at 19°C for 1 h to synchronously trap incoming virions in late endosomes prior to p38 inhibitor treatment and return to 37°C to permit uncoating. One hour was chosen because uncoating begins at 1 hpi (Fig. 3B). Samples were collected at various time points posttreatment and monitored for uncoating by Western blotting. Relative to the DMSO control, p38 inhibitor suppressed reovirus uncoating to similar extent whether added without late-endosome trafficking (Fig. 3F and H) or after viruses were first trapped in late endosomes at 19°C (Fig. 3G and H). In other words, even when endocytosis was enabled in the absence of SB202190 treatment, addition of SB202190 postendocytosis continued to prevent uncoating. Collectively, these results suggest that p38 MAPK signaling facilitates efficient reovirus uncoating by modulating transition from late endosomes to endo-lysosomes.

p38 MAPK signaling also independently enhances postuncoating steps during reovirus replication.

The p38 MAPK pathways affect many processes aside from vesicle transport, and it became important to establish if p38 MAPK effects on reovirus infection are a consequence solely of promoting virus entry or also of other processes downstream of entry. To determine if p38 MAPK inhibits postentry steps of reovirus replication, we determined the time point at which virion uncoating was mostly completed and asked if SB202190 treatment postuncoating affects subsequent steps of virus replication. Ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) was added at various time points postinfection to neutralize lysosomal compartments and inhibit further reovirus uncoating (39). The proportion of cells productively infected by reovirus was monitored at 12 hpi using flow cytometry, reasoning that at the time point when the majority of uncoating was complete, NH4Cl would no longer affect infection. Addition of NH4Cl at 0 hpi resulted in more than 90% inhibition on reovirus infection, which progressively increased with delayed addition of NH4Cl (Fig. 4A). Only a 2-fold reduction in reovirus infection was observed when NH4Cl was added at 2 hpi. When NH4Cl was added at time points after 3 hpi, minimal to no inhibition on reovirus infection was observed, suggesting that uncoating of virions essential for reovirus infection was accomplished between 3 hpi and 4 hpi (Fig. 4A).

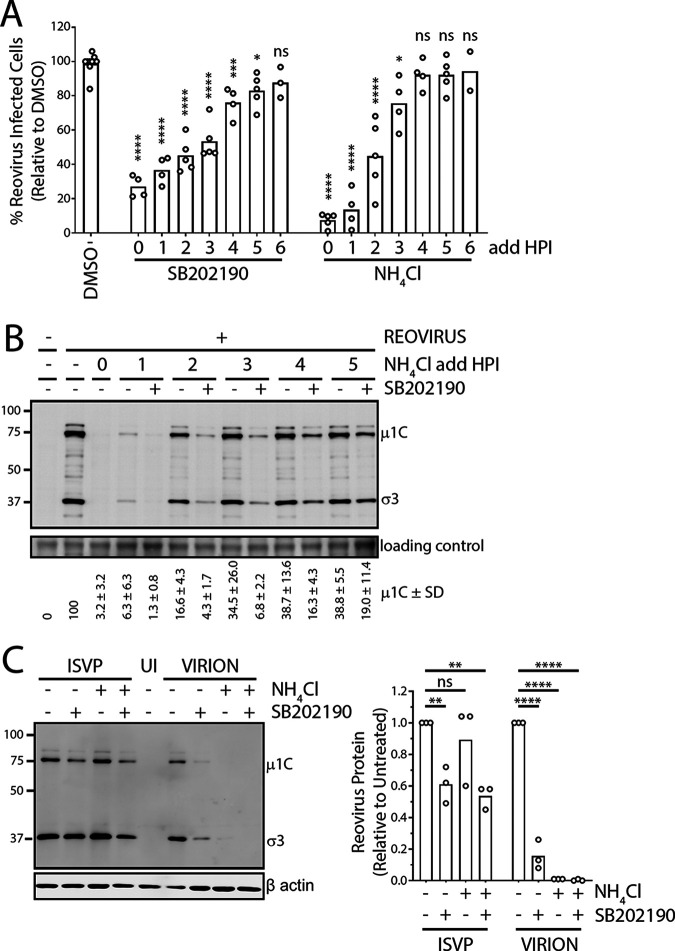

FIG 4.

p38 MAPK signaling facilitates postuncoating steps of reovirus replication. (A) L929 cells were prechilled at 4°C for 1 h, followed by reovirus (MOI, 3) addition and incubation at 4°C for 1 h. Following extensive washing to remove unbound virus, medium was replenished and cells were incubated at 37°C. At the indicated time points, NH4Cl or SB202190 was added, and cells were collected at 12 hpi for flow cytometric analysis to assess the percentage of cells positive for productive reovirus infection. (B) Similar to panel A, except that NH4Cl with or without SB202190 was added at the indicated time points. Cell lysates were collected at 12 hpi and assessed for reovirus proteins using Western blot analysis. Quantification of 2 independent experiments is provided below the blot. (C) Similar to panel A, except that cells were left uninfected (UI), or infected with either reovirus virions or ISVPs followed by treatment with or without NH4Cl and with or without SB202190 as indicated. Cell lysates were collected at 12 hpi and assessed for reovirus proteins using Western blot analysis. (Left) Representative blot of 3 independent experiments. (Right) Average de novo σ3 and μ1 plus μ1C band intensities relative to untreated control are quantified for 3 independent experiments. (A to C) In all experiments, SB202190 was used at 20 μM and NH4Cl at 10 mM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; ns, P > 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test with DMSO).

Given that uncoating is almost complete by 3 hpi, if p38 signaling promotes postuncoating steps of reovirus replication, then SB202190 added at time points after 3 hpi should still be able to reduce reovirus infection. In support of this hypothesis, even when a p38 MAPK inhibitor was added at 4 hpi, the percentage of productively infected cells was consistently reduced to ~80% relative to that of DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 4B). The effects of SB202190 treatment on percentage of infected cells diminished to insignificant levels at 6 hpi, suggesting continued dependency on p38 MAPK activity between 3 to 6 hpi despite completion of uncoating. Since measuring the percentage of reovirus-infected cells could undermine the possible effects of p38 MAPK signaling on the amount of de novo virus replication per infected cell, the effects of SB202190 on de novo reovirus protein expression were also assessed when treatments were conducted at different time points. Specifically, L929 cells were infected with reovirus for different durations prior to addition of NH4Cl to stop further uncoating. SB202190 was included or not with NH4Cl addition to assess effects of p38 MAPK signaling on de novo virus protein expression at 12 hpi by Western blotting. In agreement with the levels of reovirus infection observed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A), NH4Cl addition at ≥3 hpi led to minimal effects on de novo virus protein expression since uncoating was mostly complete (Fig. 4C). As anticipated based on results in Fig. 3, addition of SB202190 at the onset of infection (1 and 2 hpi) resulted in a >90% reduction in viral protein production, suggesting that pre-reovirus uncoating steps are inhibited by SB202190. However, at every given time point, when NH4Cl and SB202190 were combined so that p38 MAPK inhibition affected only postuncoating steps, de novo reovirus protein expression was still strongly affected by SB202190. Importantly, when SB202190 was added at 3 hpi or later, when reovirus uncoating was complete, reovirus protein synthesis was still reduced by ≥50%. Accordingly, p38 MAPK signaling plays a role in post-reovirus uncoating steps, between 3 and 6 hpi, that impact reovirus protein synthesis and productive infection.

As an alternative strategy of circumventing the endocytic pathway during reovirus infection and test effects of p38 MAPK inhibition on postuncoating steps, ISVPs generated in vitro were applied. ISVPs were previously demonstrated to bypass the lysosomal pathway by either direct entry into the cytoplasm from the external cell membrane or cytoplasmic entry from early endosomal vesicles (40). ISVPs consist of virions lacking outer capsid proteins σ3 and μ1 precleaved to δ and were generated by in vitro treatment of reovirus particles with digestive enzymes. If p38 MAPK signaling supports postuncoating steps, then SB202190 would continue to suppress reovirus infection even when cells are exposed to ISVPs. L929 cells were exposed to reovirus ISVPs in the presence or absence of SB202190 treatment for 12 h, and de novo reovirus proteins were measured by Western blotting to indicate the extent of productive infection. NH4Cl treatment did not reduce de novo virus protein expression by ISVPs (Fig. 4C, right), confirming that ISVP infection is lysosome independent. In contrast, treatment with SB202190 inhibited de novo reovirus protein synthesis even when cells were infected with ISVPs, further supporting the notion that postuncoating reovirus replication steps are dependent on p38 MAPK signaling.

Expression of p38β and p38δ MAPK isoforms correlates with reovirus uncoating in a panel of cancer cell lines.

Given that p38 signaling affects multiple stages of reovirus replication and that p38 signaling status varies among cells, we asked if there was a correlation between the p38 signaling capacity of a cancer cell and the magnitude of reovirus infection. A panel of cancer cell lines was used, including MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231, T-47D, Hs578T, BT-549, and MCF7 breast cancer cells, HCT116 colon cancer cells, and H1299 lung cancer cells. First, the panel was wholly characterized in terms of overall susceptibility to reovirus and extent of uncoating (Fig. 5). The extent of infection and uncoating was then compared to p38 isoform levels to determine if correlations exist (Fig. 6).

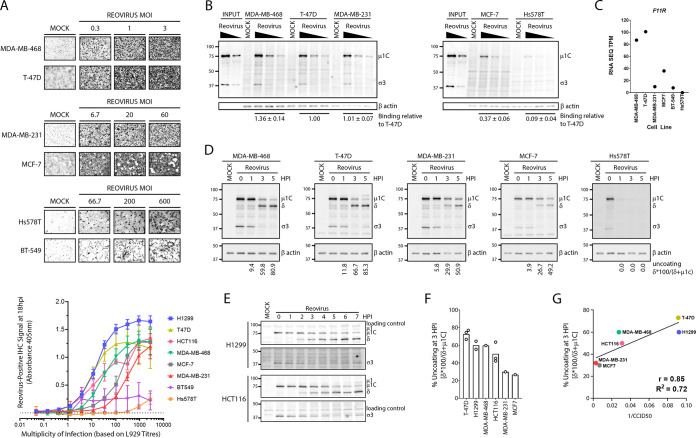

FIG 5.

Differential susceptibility of breast cancer cell lines to reovirus infection. (A) (Top) Breast cancer cell lines were infected with the indicated doses of reovirus for 12 h. Cells were fixed and virus-infected cells stained using reovirus-specific antibodies and BCIP/NBT substrate. MOIs were calculated as per titers on L929 cells. Microscopy images are representative of 2 independent experiments. (Bottom) A panel of cancer cell lines (H1299, T-47D, HCT116, MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7, BT549, and Hs578T) were infected with various doses of reovirus, fixed at 18 hpi, and stained using reovirus-specific antibodies and pNPP substrate. Absorbance at 405 was measured using a plate reader. Error bars depict SD, n = 3 for breast cancer cells, n = 4 for HCT116, and n = 6 for H1299 cells. (B) Breast cancer cell lines were exposed to reovirus (MOI, 0.3, 1, or 3) at 4°C for 1 h to permit binding and washed extensively to remove unbound virus, and cell lysates were collected at 0 hpi for detection of cell-bound viruses by Western blotting. “Input” indicates virus inoculum. (C) Basal transcript levels of F11R were obtained from the EMBL-EBI Expression Atlas database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/home) and compared between cell lines. (D to E) The indicated cells were exposed to reovirus (MOI, 3) for 1 h at 4°C for 1 h, washed extensively to remove unbound virus, and incubated at 37°C. Cell lysates were collected at the indicated time points and assessed for reovirus uncoating using Western blot analysis. (F) Quantification of percent capsid uncoating at 3 hpi for all cell lines tested. Each point on the bar graph represents an independent experiment. (G) Correlation plot of reovirus uncoating at 3 hpi versus overall susceptibility (1/CCID50 calculated from panel E).

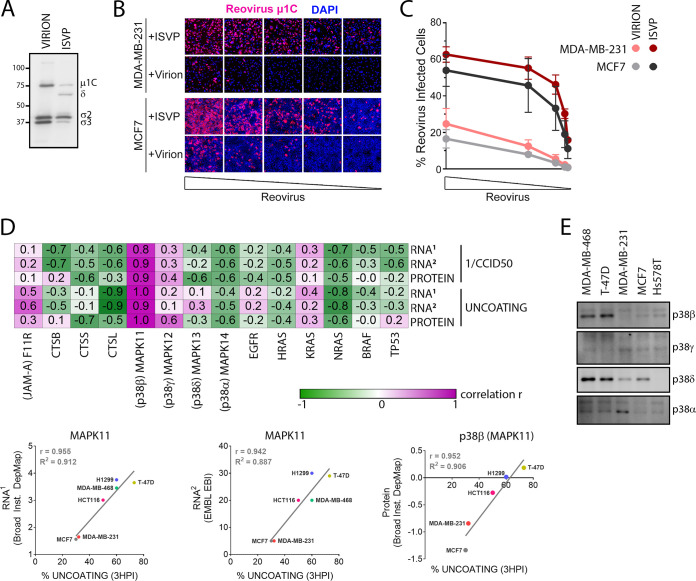

FIG 6.

Reovirus uncoating correlates with expression of p38β isoform. (A) Western blot analysis of whole virions and ISVPs using polyclonal anti-reovirus antibodies. (B, C) MCF7 or MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to serial dilutions (initial MOI, 10) of whole virions or ISVPs, normalized for equal amounts of viral particles. At 12 hpi, reovirus-infected cells were identified by immunofluorescence staining (B) or flow cytometry (C). (D) (Top) Heat map representation of correlations between indicated RNA/protein expression and reovirus uncoating/infectivity (1/CCID50) in H1299, T-47D, HCT116, MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-7 cells. RNA1, log2(TPM + 1) from Broad Institute DepMap; RNA2, TPM from EMBL-EBI Expression Atlas; Protein, normalized protein expression from Broad Institute DepMap. (Bottom) Representative correlation plots for MAPK11 (p38β) from the top. (E) The indicated cell lines were counted and normalized to 1 × 106 cells. Equal volumes of cell lysates were processed by Western blotting for p38 MAPK isoforms. Western blots are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Two approaches were used to assess the overall susceptibility of the cancer cell panel to reovirus infection. First, reovirus infection was allowed to proceed for 12 h and the frequency of productively infected cells was visualized using immunocytochemistry with reovirus-specific antibodies. Multiple doses of reovirus were used to identify a dose that establishes infection of ~50% of cells, but note that the multiplicity of infection (MOI) was calculated based on reovirus titers measured using highly susceptible L929 cells. By Poisson distribution, a cell line equally susceptible to reovirus as L929 cells should therefore show 63.2% of cells infected at an MOI of 1. Accordingly, MDA-MB-468 and T-47D cells were highly susceptible to reovirus infection, similarly to L929 cells, since multiplicities of 0.3 to 1 were sufficient to infect ≥50% of the cells (Fig. 5A, top). MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were intermediate, requiring MOIs of 20 to 60 to obtain ≥50% infected cells. Hs578T and BT-549 cells were highly resistant to initial reovirus infection, requiring ≥10 times higher MOIs than MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells for ≥50% infection. Relative to the other breast cancer cell lines in our panel, BT-549 cells had a long doubling time (~60 h) and were therefore excluded from subsequent analysis to eliminate the confounding effects of cell division.

As a more quantitative assessment of overall infectivity, the experiment described above was repeated, but instead of visualization of immunohistochemistry (IHC), the extent of reovirus protein expression was evaluated by addition of colorimetric substrate for alkaline phosphatase (AP)-labeled secondary antibodies, and optical density was used to quantify relative signal intensity (Fig. 5A, bottom). From the curves of IHC signal versus MOI, the cell culture infectious dose that led to 50% of maximal intensity (CCID50) was calculated (Fig. 5G). The higher the inverse of CCID50 (1/CCID50), the higher the overall susceptibility. Based on these results, the order of susceptibility from highest to lowest was found to be T-47D = H1299 > MDA-MB-468 = HCT116 > MDA-MB-231 = MCF7 ≫ BT549 = Hs578T.

Reovirus binds cells via cell surface junction adhesion molecule (JAM-A) and sialic acids (SA) (41), and since cells can vary in their JAM-A and SA expression levels, reovirus binding was evaluated as a potential step for differential susceptibility among breast cancer cells. Cells were exposed to reovirus at 4°C for 1 h, rinsed extensively, and subjected to Western blot analysis to measure levels of bound reovirus structural proteins. For each cell line, β-actin was normalized on a per-cell basis and used as a correction factor to account for differences in cell size, and hence plate seeding, between the cell lines. Reovirus exhibited strong attachment to the highly susceptible MDA-MB-468 and T-47D cells and the moderately susceptible MDA-MB-231 cells but only ~40% attachment to the moderately susceptible MCF7 cell line (Fig. 5B). There was very low (~10%) virus attachment to Hs578T cells, suggesting that resistance of Hs578T cells to reovirus infection is likely due to inability of the virus to bind to these cells (Fig. 5B). Using the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) cancer cell line Expression Atlas database, expression data for the primary reovirus cell binding receptor F11R (JAM-A) was evaluated. While all the other cell lines had F11R expression varying from 10 to 101 transcripts per million (TPM), Hs578T cells had zero expression (Fig. 5C), suggesting that the lack of JAM-A on Hs578T cells might contribute to poor reovirus binding and subsequent establishment of infection. As discussed below, JAM-A might serve as a possible prognostic marker to eliminate cancers that do not support reovirus infection, but given that MDA-MB-468, T-47D, MDA-MB-231, and to some extent MCF7 cancer cells still supported strong reovirus attachment yet differential susceptibility, there was rationale to assess steps downstream of reovirus binding for possible relationships to overall susceptibility.

Reovirus uncoating was monitored in the cancer cell panel by quantifying μ1C-to-δ cleavage at various time points after reovirus binding using Western blot analysis. For Hs578T cells, even though low levels of reovirus were detected immediately after binding (0 hpi), no viral protein was detected at subsequent time points (1 to 5 hpi), suggesting that the few bound virions had detached from the cells and were not internalized (Fig. 5D). In remaining cells that permitted attachment, reovirus uncoating progressed fastest in T-47D, H1299, MDA-MB-468, and HCT116 cells and slowest in the poorly susceptible MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells (Fig. 5D to F). When susceptibility (1/CCID50) was plotted against the percent uncoating at 3 hpi, there was a strong correlation (r = 0.85).

To establish if the uncoating step was truly a rate-limiting step toward reovirus infection that limited overall susceptibility in the MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 breast cancer cells, these cells were exposed to whole viruses or ISVPs, which can bypass the uncoating process for infection. Generation of ISVPs and establishment of equivalent dose were confirmed using Western blot analysis of μ1C cleavage to δ and degradation of σ3 (Fig. 6A). If uncoating is the main reason behind limited reovirus susceptibility in MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells, then reovirus ISVPs should be able to infect MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells efficiently compared to virions. MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were exposed to equivalent particles of virions or ISVPs, fixed at 12 hpi, and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6B) or flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 6C) with reovirus-specific antibodies to monitor the proportion of productively infected cells. Serial dilutions of viral particles were used to ensure that the measurements were within dynamic range of the assay and that infections by both ISVPs and virions were neither saturated nor below the limit of detection. At equal particle numbers of virions versus ISVPs, both MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were >3-fold more susceptible to infection by reovirus ISVPs compared to virions. Collectively, these results support the importance of reovirus uncoating for efficient reovirus infectivity of cancer cells.

Finally, correlation analysis was performed to determine if levels of various cellular RNA and proteins related to the overall susceptibilities and uncoating efficiencies of reovirus in the cancer cell panel (Fig. 6D). The cancer cell panel has been extensively characterized with respect to cellular mRNA expression levels and is publicly available through the EMBL-EBI Expression Atlas database and Broad Institute DepMap. BT549 and Hs-549 cells were omitted from correlation analysis since there was no infection or uncoating in these cell lines owing to the absence of binding. As for the F11R gene, which encodes the JAM-A receptor involved in reovirus attachment, while very low levels of the F11R gene corresponded with poor binding in the cell line Hs578T (Fig. 5C), for the remaining cells for which cell attachment did occur, there was only a mild positive correlation between F11R and reovirus uncoating (r = 0.3 to 0.6) and even lower correlation to overall susceptibility (r = 0.1 to 0.2). In other words, F11R and JAM-A do seem to be determinants for binding and susceptibility, although for the majority of cell lines for which binding is not a limitation, F11R and JAMA play no further role in uncoating and susceptibility. Reovirus uncoating intracellularly was previously demonstrated to depend on lysosomal cathepsins B, L, and S, yet counterintuitively, the level of each cathepsin transcript and protein was inversely correlated with the percentage of reovirus uncoating and susceptibility. There were also no strong positive correlations between susceptibility or uncoating with EGFR, Hras, Kras, Nras, Braf, or p53; this was not surprising since these cancer cells are all transformed and therefore the Ras and p53 pathways are likely dysregulated independently of direct expression levels of Ras or p53 itself. Of the four p38 MAPK isoforms, MAPK13 and MAPK14 RNAs, as well as their protein products p38δ and p38α, showed poor correlation with reovirus uncoating and overall susceptibility. The expression of MAPK12 (encodes p38γ) showed moderate (r = 0.1 to 0.6) correlation to reovirus uncoating and susceptibility. Strikingly, MAPK11 and the corresponding p38β protein isoform demonstrated a very strong correlation to reovirus susceptibility (r = 0.8 to 0.9) and uncoating (r = 0.9 to 1.0) (Fig. 6D, bottom). Finally, to further validate that p38 MAPK isoform expression in the breast cancer cell lines used in our laboratory corresponds with published protein expression data, protein levels of p38 MAPK isoforms were determined by Western blotting using isoform-specific antibodies. All cell lines were standardized to equivalent number of cells per microliter of lysate to account for differences in cell size. Similar to published RNA and protein levels from the databases used in our analysis, protein expression levels of the p38β and p38δ isoforms were high in MDA-MB-468 and T-47D cells, the two cell lines with the fastest reovirus uncoating. Together with the correlation analysis, these results suggest that the MAPK11 gene and its p38β protein isoform offer the strongest association with efficiency of reovirus uncoating and infection.

DISCUSSION

Ongoing clinical trials with Pelareorep include prescreening patients for activation and/or overexpression mutations in the EGFR, Hras, Kras, Nras, Braf, and p53 genes. However, the inclusion of these prognostic markers has shown very limited success, likely due to these biomarkers being the most commonly occurring mutations in cancers. Additionally, since EGFR and its Ras signaling cascade trigger a wide array of downstream events, an aberrant cancer-inducing mutation in a downstream pathway will nullify the use of EGFR and Ras as prognostic markers. Therefore, there is a need to identify novel downstream prognostic markers associated with enhanced reovirus infection. In this study, we identified p38 MAPK signaling as an essential pathway for establishment of reovirus infection, specifically during reovirus endocytosis, lysosomal uncoating, and postuncoating steps. Moreover, using a breast cancer cell line panel, we demonstrated that reovirus uncoating correlates with expression of p38β.

During reovirus infection, trafficking of the virion to the endo-lysosome is a rate-limiting step; virions in early endosomes are unable to initiate infection, while virions in endo-lysosomes for an extended duration are inactivated (42). Our results suggest that p38 MAPK signaling mediates internalized reovirus vesicular trafficking to endo-lysosomes. Specifically, treatment with a p38 inhibitor restricts intracellular reovirus uncoating, internalized virions reside in larger vesicles following p38 inhibition, and impedance of late endosome and lysosome fusion restricts reovirus uncoating in p38 inhibitor-treated cells. The p38 MAPK signaling pathway is involved in various aspects of endosome trafficking. Endosomes are classified in accordance with the presence of specific markers: Rab5 and early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) for early endosomes and Rab7 and Rab9 for late endosomes (37, 38). It was demonstrated that phosphorylation of guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (GDI) by p38 MAPK results in formation of cytoplasmic P-GDI-Rab5 complexes which are required for Rab5 delivery, docking, and loading onto early endosome membranes. Artificial activation of p38 MAPK using hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or UV treatment increased internalization rates and early endosome formation, whereas inhibition of p38 MAPK using SB203580 had the opposite phenotype of decreased internalization rates and early endosome formation (43, 44). Therefore, our observation that p38 MAPK signaling modulates reovirus internalization could potentially be related to p38 MAPK-GDI-Rab5-mediated early endosome formation. Moreover, our result of internalized fluorescent virions forming larger vesicles in the presence of a p38 MAPK inhibitor could also be an indication of defective early endosome formation.

Extrusion of Rab5 from early endosome membranes occurs concurrently with loading of Rab7, resulting in the transition to late endosomes. Rab7-containing late endosomes are the site of lysosome fusion and subsequent degradation of endosomal contents (38, 45). In our temperature-controlled endosomal trafficking experiment, we established that incubation at 19°C allows endocytosis; however, virus uncoating fails to occur, indicating a block in access to lysosomal contents. When reovirus-infected cells at 19°C were moved to 37°C, reovirus uncoating progressed, suggesting successful interaction of virions with lysosomal contents. Interestingly, in the presence of a p38 MAPK inhibitor, reovirus uncoating did not occur when cells were moved from 19°C to 37°C, proposing a p38 MAPK-regulated defect in late endosome/lysosome fusion and/or lysosome biogenesis. Indeed, p38 MAPK was demonstrated to phosphorylate LAMP2A bound to lysosomes, resulting in dysfunctional lysosomal biogenesis (46).

Establishment of a virus infection in cells relies on the success of multiple steps: binding, entry, viral genome replication, viral protein synthesis, virion assembly, and virus release. Hence, successful identification of prognostic markers requires in-depth understanding of host signaling pathways important during each stage of the virus replication cycle. In a panel of breast cancer cell lines, we quantified reovirus binding and uncoating and attempted to correlate their efficiency with the presence of previously established factors important in these steps. Reovirus binding to cells occurs via cell surface JAM-A (F11R) and sialic acids, whereas endocytosis is triggered by interaction with β1 integrin (47–49). In our breast cancer cell line panel analysis, we observed that any expression of F11R, whether low or high, was sufficient for reovirus binding. However, lack of F11R expression abrogated reovirus binding, suggesting that F11R could be utilized as a potential tumor biomarker to assess for reovirus binding. In a study performed by Kelly et al. with a panel of advanced multiple myeloma cell lines, they also observed that lack of F11R (JAM-A) restricted reovirus infection, further supporting the use of F11R (JAM-A) as a prognostic marker for reovirus therapy (50). Reovirus uncoating is modulated by lysosomal cathepsins (51); however, none of the cathepsins (CTSB, CTSS, and CTSL) were positively correlated with the rate of reovirus uncoating, at least at the transcript level. Strikingly, we observed a very strong positive correlation between MAPK11 (p38β) and the rate of reovirus uncoating, upholding our evidence for the importance of p38 MAPK signaling in reovirus entry and uncoating.

In summary, our study elucidates the functional importance of p38 MAPK signaling during reovirus entry, uncoating, and postuncoating steps during infection and identifies the p38β isoform as a potential biomarker for reovirus uncoating and overall susceptibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

All cell lines were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2, and all media were supplemented with 1× antibiotic antimycotic (A5955; Millipore Sigma). Except for NIH 3T3 medium, which was supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum (NCS; N4637; Millipore Sigma), all media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; F1051; Millipore Sigma). The L929, NIH 3T3, H1299, and B16-F10 cell lines (Patrick Lee, Dalhousie University) were generous gifts. The BT-549, Hs578T, MCF7, T-47D, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-468 cell lines were purchased from the ATCC as part of the NCI-60 cell line panel. L929 cells were cultured in minimal essential medium (MEM; M4655, Millipore Sigma) supplemented with 1× nonessential amino acids (M7145; Millipore Sigma) and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (S8636; Millipore Sigma). The L929 cell line in suspension was cultured in Joklik’s modified MEM (pH 7.2; M0518; Millipore Sigma) supplemented with 2 g/L sodium bicarbonate (BP328; Fisher Scientific), 1.2 g/L HEPES (BP310; Fisher Scientific), 1× nonessential amino acids (M7145; Millipore Sigma), and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (S8636; Millipore Sigma). The H1299, BT-549, Hs578T, MCF7, T-47D, MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-468 cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 (R8758; Millipore Sigma). The NIH 3T3 and B16-F10 cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM; D5796; Millipore Sigma) supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (S8636; Millipore Sigma). All cell lines were routinely assessed for mycoplasma contamination using 0.5 μg/mL Hoechst 33352 (H1399; Thermo Fisher Scientific) staining or PCR (G238; ABM).

Reovirus stocks.

T3D virus seed stock lysates were plaque purified, and second- or third-passage L929 cell lysates were used as large-scale suspension culture inocula. Virus stocks were cesium chloride gradient purified, and virus titers were determined on L929 cells as previously described in detail (1).

Antibodies.

The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-reovirus polyclonal antibody (pAb; 1:10,000) from Patrick Lee (Dalhousie University), rabbit anti-P-p38 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology [CST]; catalogue no. 9215S), rabbit anti-p38 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology [SCBT]; catalogue no. SC-535), mouse anti-β-actin (1:1,000; SCBT; catalogue no. 47778), mouse anti-reovirus μ1C (1:500; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB]; catalogue no. 10F6), rabbit anti-P-ATF2 (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 5112S), rabbit anti-P-MKK3/6 (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 9231S), rabbit anti-P-MSK1 (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 9595P), rabbit anti-P-MNK1 (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 2111S), rabbit anti-p38α (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 9218), rabbit anti-p38β (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 2339), rabbit anti-p38δ (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 2308), rabbit anti-p38γ (1:1,000; CST; catalogue no. 2307), goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch [JIR]; catalogue no. 111-035-144), goat anti-mouse HRP (1:10,000; JIR; catalogue no. 115-035-146), goat anti-rabbit AP (1:10,000; JIR; catalogue no. 111-055-144), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 (1:2,000; JIR; catalogue no. 111-605-144), goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:2,000; JIR; catalogue no. 111-545-144), and goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 (1:2,000; JIR; catalogue no. 115-605-146).

Inhibitor and treatment compounds.

Inhibitor and treatment compounds included SB202190 (100 mM in DMSO; Millipore Sigma; catalogue no. S7067), SB203580 (50 mM in DMSO, Millipore Sigma; catalogue no. S8307), SB202474 (50 mM in DMSO; Millipore Sigma; catalogue no. 559387), anisomycin (18.85 mM in DMSO; Millipore Sigma; catalogue no. A9789), BIRB-796 (125.6 mM in DMSO; Millipore Sigma; catalogue no. 506172), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl; 4 M in H2O; Millipore Sigma; catalogue no. A9434), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; 100 mM in H2O; Fisher Scientific; catalogue no. H312-500).

Reovirus infection.

Cells were prechilled at 4°C for 1 h, followed by reovirus addition (MOI, 3) and incubation at 4°C for an additional hour to facilitate reovirus binding. Virus inoculum was removed, cells were rinsed three times to remove unbound virus, and incubation proceeded at 37°C unless indicated otherwise. For Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated virions, an MOI of 20 was used.

Radiolabeled (35S) reovirus virions.

At 9 h after reovirus infection of L929 cells, cells were washed and medium was replaced with methionine-cysteine-free medium supplemented with [35S]methionine at 100 μCi/mL and dialyzed FBS at a 10% final concentration. At 20 hpi, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630 [NP-40], 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (11873580001; Roche). The lysate was layered on a 20% sucrose cushion and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C. The pellet containing radiolabeled reovirus was resuspended in PBS and stored at 4°C.

Fluorescence (Alexa Fluor 546)-labeled reovirus virions.

Reovirus stock was diluted to 3 × 1012 particles in freshly made 0.05 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 8.5), and Alexa Fluor 546 dye (A20002; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to a 12 μM final dye concentration. After incubation at 4°C for 90 min, an overnight dialysis (molecular weight cutoff [MWCO], 10 to 20 kDa) in PBS was performed and virus was collected, virus titer was determined, and virus was stored at 4°C.

Drug assays.

Cells were pretreated for 1 h with the indicated compound or respective DMSO control prior to virus addition, and compound was maintained for the duration of the virus infection. For the low-temperature endocytosis assays, compound was added after 19°C incubation. For the time-of-addition assays, compound was added at the indicated time point and maintained for the duration of infection.

Resazurin cell viability assay.

L929 cells were treated with p38 MAPK inhibitors, inactive analogue, or hydrogen peroxide at indicated doses for 12 h, followed by compound removal, medium replenishment, and additional incubation for 12 h. Immediately prior to addition to wells, resazurin stock solution was diluted 1/10 in PBS and 10 μL was added per 96 wells. Samples were read on a plate reader (FLUOstar Optima; BMG Lab Tech) every 30 min for 2 h, until signal saturation. Fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 520 nm and an emission wavelength of 584 nm. Resazurin stock solution was prepared at 440 μM in PBS and stored in aliquots at 4°C.

Western blot analysis.

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (11873580001; Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 50 mM sodium fluoride). Following addition of 5× protein sample buffer (250 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 5% SDS, 45% glycerol, 9% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) for a final concentration of 1× protein sample buffer, samples were heated for 5 min at 100°C and loaded onto SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After SDS-PAGE, separated proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using the Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)–Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T; blocking buffer) and incubated with primary and secondary antibodies, with 3 wash steps between antibody incubation steps. Membranes with HRP-conjugated antibodies were exposed to ECL Plus Western blotting substrate (32132; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were visualized using an ImageQuant LAS4010 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Flow cytometry.

Cells were detached with trypsin and washed with medium containing FBS to quench trypsin. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min, followed by permeabilization and blocking in 3% BSA–PBS–Triton X-100 at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were spiked with primary antibody (rabbit anti-reovirus pAb, 1:10,000; mouse anti-reovirus μ1C, 1:500) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed twice and incubated with secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647, 1:2,000; goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647, 1:1,000) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were washed twice and analyzed using FACSCanto (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FCS Express 5 (De Novo Software). A minimum of 10,000 total cells were collected for each sample.

ISVP infections.

Reovirus (T3DT249I) stock was diluted in virus dilution buffer (150 mM NaCl, 15 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]) containing mouse intestinal extract (10% [vol/vol]). Virus-intestinal extract mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by neutralization using equal volume of MEM (M4655; Millipore Sigma) supplemented with 5% FBS (F1051; Millipore Sigma).

Reovirus infectivity staining.

At the indicated time point postinfection, growth medium was removed and cells were washed once with PBS. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. After discarding the paraformaldehyde, cells were washed twice with PBS before blocking for 1 h at room temperature in 3% BSA–PBS–0.1% Triton X-100 (blocking buffer). Blocking buffer was then replaced with primary anti-reovirus antibodies (mouse anti-reovirus μ1C or rabbit anti-reovirus pAb) diluted in blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, following removal of primary antibodies, cells were washed thrice with PBS–0.1% Triton X-100 (wash buffer) and incubated with secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 for fluorescence or goat anti-rabbit AP for colorimetry) in blocking buffer. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1:4,000 in blocking buffer; D1306; Invitrogen) was added as a nuclear counterstain for fluorescence imaging for 1 h at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were discarded and cells were washed thrice with wash buffer. For visual colorimetry, Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT; 300 μg/mL; B8503; Millipore Sigma) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP; 150 μg/mL; N6639; Millipore Sigma) substrates were diluted in AP buffer (100 mM Tris [pH 9.5], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2) and incubated on cells for 30 min. Reactions were stopped by addition of PBS–5 mM EDTA. PBS was then added to each well and imaged on an EVOS FL autoimaging system (Life Technologies). For absorbance measurements, 4-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate (pNPP) (4 mg/mL; CA97061-486; VWR) substrate diluted in diethanolamine buffer was added to cells and incubated for 2 h, followed by absorbance measurements at 405 nm on a plate reader.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This publication is supported through project grants to M.S. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Cancer Research Society (CRS), the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute (CCSRI), a salary award to M.S. from the Canada Research Chairs (CRC), and infrastructure support to M.S. from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI). A.M. received scholarships from an Alberta Cancer Foundation Graduate Studentship, a University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry/Alberta Health Services Graduate Recruitment Studentship, and a University of Alberta Doctoral Recruitment Award. Q.F.L. received scholarships from a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s (CGS M) award, Walter H. Johns Graduate Fellowship award, and Marathon of Hope Graduate Studentship. Flow cytometry was performed at the University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Flow Cytometry Facility, and confocal microscopy was performed at the University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Cell Imaging Core, which receive financial support from the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry and Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Contributor Information

Maya Shmulevitz, Email: shmulevi@ualberta.ca.

Susana López, Instituto de Biotecnologia/UNAM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohamed A, Clements DR, Gujar SA, Lee PW, Smiley JR, Shmulevitz M. 2020. Single amino acid differences between closely related reovirus T3D lab strains alter oncolytic potency in vitro and in vivo. J Virol 94:e01688-19. 10.1128/JVI.01688-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller L, Berkeley R, Barr T, Ilett E, Errington-Mais F. 2020. Past, present and future of oncolytic reovirus. Cancers (Basel) 12:3219. 10.3390/cancers12113219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein V, Ellard SL, Dent SF, Tu D, Mates M, Dhesy-Thind SK, Panasci L, Gelmon KA, Salim M, Song X, Clemons M, Ksienski D, Verma S, Simmons C, Lui H, Chi K, Feilotter H, Hagerman LJ, Seymour L. 2018. A randomized phase II study of weekly paclitaxel with or without pelareorep in patients with metastatic breast cancer: final analysis of Canadian Cancer Trials Group IND.213. Breast Cancer Res Treat 167:485–493. 10.1007/s10549-017-4538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gong J, Sachdev E, Mita AC, Mita MM. 2016. Clinical development of reovirus for cancer therapy: an oncolytic virus with immune-mediated antitumor activity. World J Methodol 6:25–42. 10.5662/wjm.v6.i1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcato P, Shmulevitz M, Lee PW. 2005. Connecting reovirus oncolysis and Ras signaling. Cell Cycle 4:556–559. 10.4161/cc.4.4.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan D, Marcato P, Ahn DG, Gujar S, Pan LZ, Shmulevitz M, Lee PW. 2013. Activation of p53 by chemotherapeutic agents enhances reovirus oncolysis. PLoS One 8:e54006. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan D, Pan LZ, Hill R, Marcato P, Shmulevitz M, Vassilev LT, Lee PW. 2011. Stabilisation of p53 enhances reovirus-induced apoptosis and virus spread through p53-dependent NF-kappaB activation. Br J Cancer 105:1012–1022. 10.1038/bjc.2011.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shmulevitz M, Lee PW. 2012. Exploring host factors that impact reovirus replication, dissemination, and reovirus-induced cell death in cancer versus normal cells in culture. Methods Mol Biol 797:163–176. 10.1007/978-1-61779-340-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shmulevitz M, Marcato P, Lee PW. 2010. Activated Ras signaling significantly enhances reovirus replication and spread. Cancer Gene Ther 17:69–70. 10.1038/cgt.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shmulevitz M, Pan LZ, Garant K, Pan D, Lee PW. 2010. Oncogenic Ras promotes reovirus spread by suppressing IFN-beta production through negative regulation of RIG-I signaling. Cancer Res 70:4912–4921. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Liu HT. 2002. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res 12:9–18. 10.1038/sj.cr.7290105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braicu C, Buse M, Busuioc C, Drula R, Gulei D, Raduly L, Rusu A, Irimie A, Atanasov AG, Slaby O, Ionescu C, Berindan-Neagoe I. 2019. A comprehensive review on MAPK: a promising therapeutic target in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 11:1618. 10.3390/cancers11101618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman KL, Hirasawa K, Yang AD, Shields MA, Lee PW. 2004. Reovirus oncolysis: the Ras/RalGEF/p38 pathway dictates host cell permissiveness to reovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11099–11104. 10.1073/pnas.0404310101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng Y, Sun F, Wang L, Gao M, Xie Y, Sun Y, Liu H, Yuan Y, Yi W, Huang Z, Yan H, Peng K, Wu Y, Cao Z. 2020. Virus-induced p38 MAPK activation facilitates viral infection. Theranostics 10:12223–12240. 10.7150/thno.50992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borgeling Y, Schmolke M, Viemann D, Nordhoff C, Roth J, Ludwig S. 2014. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase impairs influenza virus-induced primary and secondary host gene responses and protects mice from lethal H5N1 infection. J Biol Chem 289:13–27. 10.1074/jbc.M113.469239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarn C, Zou L, Hullinger RL, Andrisani OM. 2002. Hepatitis B virus X protein activates the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in dedifferentiated hepatocytes. J Virol 76:9763–9772. 10.1128/jvi.76.19.9763-9772.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang WR, Wang YC, Chi PI, Wang L, Wang CY, Lin CH, Liu HJ. 2011. Cell entry of avian reovirus follows a caveolin-1-mediated and dynamin-2-dependent endocytic pathway that requires activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Src signaling pathways as well as microtubules and small GTPase Rab5 protein. J Biol Chem 286:30780–30794. 10.1074/jbc.M111.257154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark JE, Sarafraz N, Marber MS. 2007. Potential of p38-MAPK inhibitors in the treatment of ischaemic heart disease. Pharmacol Ther 116:192–206. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweeney G, Somwar R, Ramlal T, Volchuk A, Ueyama A, Klip A. 1999. An inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase prevents insulin-stimulated glucose transport but not glucose transporter translocation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and L6 myotubes. J Biol Chem 274:10071–10078. 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams RH, Porras A, Alonso G, Jones M, Vintersten K, Panelli S, Valladares A, Perez L, Klein R, Nebreda AR. 2000. Essential role of p38alpha MAP kinase in placental but not embryonic cardiovascular development. Mol Cell 6:109–116. 10.1016/S1097-2765(05)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mudgett JS, Ding J, Guh-Siesel L, Chartrain NA, Yang L, Gopal S, Shen MM. 2000. Essential role for p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase in placental angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:10454–10459. 10.1073/pnas.180316397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S, Jiang MS, Adams JL, Lee JC. 1999. Pyridinylimidazole compound SB 203580 inhibits the activity but not the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 263:825–831. 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young PR, McLaughlin MM, Kumar S, Kassis S, Doyle ML, McNulty D, Gallagher TF, Fisher S, McDonnell PC, Carr SA, Huddleston MJ, Seibel G, Porter TG, Livi GP, Adams JL, Lee JC. 1997. Pyridinyl imidazole inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase bind in the ATP site. J Biol Chem 272:12116–12121. 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Levy R, Hooper S, Wilson R, Paterson HF, Marshall CJ. 1998. Nuclear export of the stress-activated protein kinase p38 mediated by its substrate MAPKAP kinase-2. Curr Biol 8:1049–1057. 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han X, Chen H, Zhou J, Steed H, Postovit LM, Fu Y. 2018. Pharmacological inhibition of p38 MAPK by SB203580 increases resistance to carboplatin in A2780cp cells and promotes growth in primary ovarian cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 19:2184. 10.3390/ijms19082184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meng M, Chen Y, Chen X, Zhang Q, Guo W, Zhou X, Zou J. 2020. IL-1alpha regulates osteogenesis and osteoclastic activity of dental follicle cells through JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Stem Cells Dev 29:1552–1566. 10.1089/scd.2020.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miura H, Kondo Y, Matsuda M, Aoki K. 2018. Cell-to-cell heterogeneity in p38-mediated cross-inhibition of JNK causes stochastic cell death. Cell Rep 24:2658–2668. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverstein SC, Astell C, Levin DH, Schonberg M, Acs G. 1972. The mechanisms of reovirus uncoating and gene activation in vivo. Virology 47:797–806. 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Punnonen EL, Ryhänen K, Marjomäki VS. 1998. At reduced temperature, endocytic membrane traffic is blocked in multivesicular carrier endosomes in rat cardiac myocytes. Eur J Cell Biol 75:344–352. 10.1016/s0171-9335(98)80067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haylett T, Thilo L. 1991. Endosome-lysosome fusion at low temperature. J Biol Chem 266:8322–8327. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)92978-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentzsch M, Chang XB, Cui L, Wu Y, Ozols VV, Choudhury A, Pagano RE, Riordan JR. 2004. Endocytic trafficking routes of wild type and DeltaF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mol Biol Cell 15:2684–2696. 10.1091/mbc.e04-03-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ludwig T, Griffiths G, Hoflack B. 1991. Distribution of newly synthesized lysosomal enzymes in the endocytic pathway of normal rat kidney cells. J Cell Biol 115:1561–1572. 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schober D, Kronenberger P, Prchla E, Blaas D, Fuchs R. 1998. Major and minor receptor group human rhinoviruses penetrate from endosomes by different mechanisms. J Virol 72:1354–1364. 10.1128/JVI.72.2.1354-1364.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prchla E, Kuechler E, Blaas D, Fuchs R. 1994. Uncoating of human rhinovirus serotype 2 from late endosomes. J Virol 68:3713–3723. 10.1128/JVI.68.6.3713-3723.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunn WA, Hubbard AL, Aronson NN, Jr. 1980. Low temperature selectively inhibits fusion between pinocytic vesicles and lysosomes during heterophagy of 125I-asialofetuin by the perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem 255:5971–5978. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)70726-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baravalle G, Schober D, Huber M, Bayer N, Murphy RF, Fuchs R. 2005. Transferrin recycling and dextran transport to lysosomes is differentially affected by bafilomycin, nocodazole, and low temperature. Cell Tissue Res 320:99–113. 10.1007/s00441-004-1060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott CC, Vacca F, Gruenberg J. 2014. Endosome maturation, transport and functions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 31:2–10. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huotari J, Helenius A. 2011. Endosome maturation. EMBO J 30:3481–3500. 10.1038/emboj.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Canning WM, Fields BN. 1983. Ammonium chloride prevents lytic growth of reovirus and helps to establish persistent infection in mouse L cells. Science 219:987–988. 10.1126/science.6297010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borsa J, Morash BD, Sargent MD, Copps TP, Lievaart PA, Szekely JG. 1979. Two modes of entry of reovirus particles into L cells. J Gen Virol 45:161–170. 10.1099/0022-1317-45-1-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandes JP, Cristi F, Eaton HE, Chen P, Haeflinger S, Bernard I, Hitt MM, Shmulevitz M. 2019. Breast tumor-associated metalloproteases restrict reovirus oncolysis by cleaving the sigma1 cell attachment protein and can be overcome by mutation of σ1. J Virol 93:e01380-19. 10.1128/JVI.01380-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mainou BA, Dermody TS. 2011. Src kinase mediates productive endocytic sorting of reovirus during cell entry. J Virol 85:3203–3213. 10.1128/JVI.02056-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]