ABSTRACT

Coinfection of human papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been detected in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Although HPV and EBV replicate in differentiated epithelial cells, we previously reported that HPV epithelial immortalization reduces EBV replication within organotypic raft culture and that the HPV16 oncoprotein E7 was sufficient to inhibit EBV replication. A well-established function of HPV E7 is the degradation of the retinoblastoma (Rb) family of pocket proteins (pRb, p107, and p130). Here, we show that pRb knockdown in differentiated epithelia and EBV-positive Burkitt lymphoma (BL) reduces EBV lytic replication following de novo infection and reactivation, respectively. In differentiated epithelia, EBV immediate early (IE) transactivators were expressed, but loss of pRb blocked expression of the early gene product, EA-D. Although no alterations were observed in markers of epithelial differentiation, DNA damage, and p16, increased markers of S-phase progression and altered p107 and p130 levels were observed in suprabasal keratinocytes after pRb knockdown. In contrast, pRb interference in Akata BX1 Burkitt lymphoma cells showed a distinct phenotype from differentiated epithelia with no significant effect on EBV IE or EA-D expression. Instead, pRb knockdown reduced the levels of the plasmablast differentiation marker PRDM1/Blimp1 and increased the abundance of c-Myc protein in reactivated Akata BL with pRb knockdown. c-Myc RNA levels also increased following the loss of pRb in epithelial rafts. These results suggest that pRb is required to suppress c-Myc for efficient EBV replication in BL cells and identifies a mechanism for how HPV immortalization, through degradation of the retinoblastoma pocket proteins, interferes with EBV replication in coinfected epithelia.

IMPORTANCE Terminally differentiated epithelium is known to support EBV genome amplification and virion morphogenesis following infection. The contribution of the cell cycle in differentiated tissues to efficient EBV replication is not understood. Using organotypic epithelial raft cultures and genetic interference, we can identify factors required for EBV replication in quiescent cells. Here, we phenocopied HPV16 E7 inhibition of EBV replication through knockdown of pRb. Loss of pRb was found to reduce EBV early gene expression and viral replication. Interruption of the viral life cycle was accompanied by increased S-phase gene expression in postmitotic keratinocytes, a process also observed in E7-positive epithelia, and deregulation of other pocket proteins. Together, these findings provide evidence of a global requirement for pRb in EBV lytic replication and provide a mechanistic framework for how HPV E7 may facilitate a latent EBV infection through its mediated degradation of pRb in copositive epithelia.

KEYWORDS: HPV, EBV, organotypic raft, replication, cell cycle, epithelium, Epstein-Barr virus, human papillomavirus

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous DNA tumor virus found in over 90% of the human population as a lifelong infection (1, 2). Such lifelong infections result from latent infection and viral lytic reactivation in B lymphocytes and productive lytic replication in the epithelium. EBV infections are typically benign, but in rare cases, EBV has been implicated as the causative agent in a variety of diseases, including infectious mononucleosis, B and epithelial cell malignancies, and multiple sclerosis (3–10). Both latent and lytic phases of the EBV life cycle have been implicated in pathogenesis. In EBV-associated cancers, such as Burkitt lymphoma (BL), nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), and gastric carcinoma, latent EBV infection and expression of viral oncoproteins are associated with aberrant cell growth and survival. However, high viral loads and elevated antibody titers against EBV lytic proteins have been observed to precede the clinical onset of BL and NPC, implicating viral replication in the early development of EBV-associated cancers (11–14).

EBV lytic replication is regulated by host and viral transcription factors. Although lytic replication can be activated by various means in vitro, cellular differentiation is a physiological signal for activation of the EBV lytic gene expression cascade (15–18). Within the epithelium, expression of cellular differentiation transcription factors Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) and PR domain zinc finger protein 1 (PRDM1) are required for expression of EBV immediate early (IE) BRLF1 and BZLF1 genes (19, 20). In B cells, memory B cell differentiation to a plasma cell and expression of PRDM1 also initiate expression of IE genes (15). BZLF1 and BRLF1 genes encode viral transactivators Z and R, which trigger a cascade of viral gene expression, leading to sequential expression of early and late EBV genes (21–26). Early genes encode the viral DNA replication machinery, such as the viral processivity factor (EA-D), which facilitates genome amplification. The IE Z transactivator also coordinates replication with the viral gene expression cascade through binding and activation of the EBV lytic origin of DNA replication, OriLyt (27). Late genes include structural proteins that encapsidate newly synthesized viral genomes for transmission and spread.

In EBV-associated carcinomas, EBV is found as a latent infection, suggesting interruption of viral replication in these cancer tissues. In NPC, evidence suggests that interruption of the viral life cycle is mediated by preexisting genetic alterations found in premalignant lesions that facilitate a latent EBV infection (28–30). Common alterations observed are the overexpression of cyclin D1 and loss of p16. Cyclin D1 and p16 are cellular factors that, along with the retinoblastoma (Rb) family of pocket proteins, are involved in regulation of the cell cycle. These genetic alterations can occur due to exposure to environmental carcinogens or infection with another virus, such as human papillomavirus (HPV). We previously observed that a subset of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) was coinfected with EBV and HPV (31). By modeling EBV and HPV coinfections in organotypic raft culture, we observed that EBV replication was inhibited in HPV-immortalized tissues and that HPV16 E7 was sufficient to reduce EBV lytic replication (32). HPV E7 has no known enzymatic activities or DNA binding domains but acts primarily as a transcriptional regulator that is essential for HPV genome amplification and virion morphogenesis. Most notably, HPV E7 is known to bind and facilitate the degradation of the Rb family of pocket proteins, which include family members pRb (p105), p107, and p130 (33, 34).

Pocket proteins are classically described for their role in the regulation of cell cycle progression. pRb was the first identified tumor suppressor and has been well characterized to control the G1/S transition during the cell cycle (35). During G0, hypophosphorylated pRb binds activator E2F transcription factor family members and restricts cell cycle progression. In late G1, hyperphosphorylation of pRb via cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes results in pRb dissociation from activator E2Fs, expression of S-phase genes, and progression to S phase (36–38). In contrast, p130 and p107 alternatively bind repressive E2F family members in the dimerization partner, Rb-like, E2F, and multivulval class B (DREAM) complex to repress cell cycle gene expression during G0 (39). p107/p130 dissociation results in destabilization of the DREAM complex and release of the repression of cell cycle gene expression, thereby promoting progression to G1.

pRb has also been implicated in the regulation of cellular differentiation, chromatin stability, and apoptosis. pRb binds and restricts the activity of the inhibitor of differentiation 2 (ID2) to promote cellular differentiation (40, 41). In addition, knockout of pRb is lethal in embryonic mice, as both the hematopoietic and nervous system fail to develop properly (42). Furthermore, hypophosphorylated pRb has been noted to persist in differentiating cells, supporting the role of pRb in promoting epithelial differentiation while restricting cell cycle progression (43, 44). pRb regulates chromatin stability through recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes that can function to activate or repress transcription at sites with E2F and other transcription factors (45–48). Independently of transcriptional control, pRb also serves as a protein adaptor to facilitate target protein degradation (49, 50).

Modulation of pRb activity has been documented during the EBV life cycle; however, it is unclear whether pRb is required for EBV replication. The IE transactivator R can bind to pRb outside the E2F binding pocket at early times after induction of lytic replication in B cells (51). Lytic replication in B cells has also been associated with an accumulation of hyperphosphorylated pRb (52). In contrast, the EBV-encoded protein kinase BGLF4 has been reported to phosphorylate pRb but did not facilitate release of E2F (53). In fact, BGLF4 expression resulted in a delay in S-phase progression and an interruption of cellular DNA synthesis. Consistent with these results, EBV replication has been reported to occur in the absence of cellular DNA synthesis in a G0/G1 to early S-phase environment (54, 55).

Here, we examined whether EBV requires pRb for lytic replication following de novo infection in differentiated epithelia and reactivation in EBV-positive Akata BX1 Burkitt lymphoma cells (here termed Akata BL). Organotypic raft cultures were used to promote the stratification and differentiation of epithelial cells, providing a physiologically relevant model to study EBV replication in differentiated epithelia (56). Partial pRb knockdown (KD) in raft tissues and in Akata BL was achieved after small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection. In differentiated epithelium, we observed S-phase progression in suprabasal keratinocytes, consistent with a functional effect after loss of pRb, and epithelial differentiation was preserved. We also observed deregulation of other pocket protein family members, p107 and p130, in pRb KD rafts, consistent with S-phase progression. Following pRb KD in keratinocytes grown in organotypic raft culture, EBV replication was reduced compared to that in controls. Interestingly, expression of the IE BRLF1 gene and gene product Z correlated with EBV DNA foci regardless of pRb levels. In contrast, the early gene product EA-D and late gene product gp350 were significantly reduced in tissue areas that correlated with loss of pRb. In Akata BL, pRb KD also resulted in reduced EBV DNA replication following EBV reactivation from latency. However, EBV IE and BMRF1 gene expression were not affected. Instead, loss of pRb appeared to interfere with B cell differentiation based on PRDM1/Blimp1 expression and increased expression of c-Myc. Together, these results indicate that EBV requires pRb for efficient lytic replication in differentiated epithelia and latently infected BL cells.

RESULTS

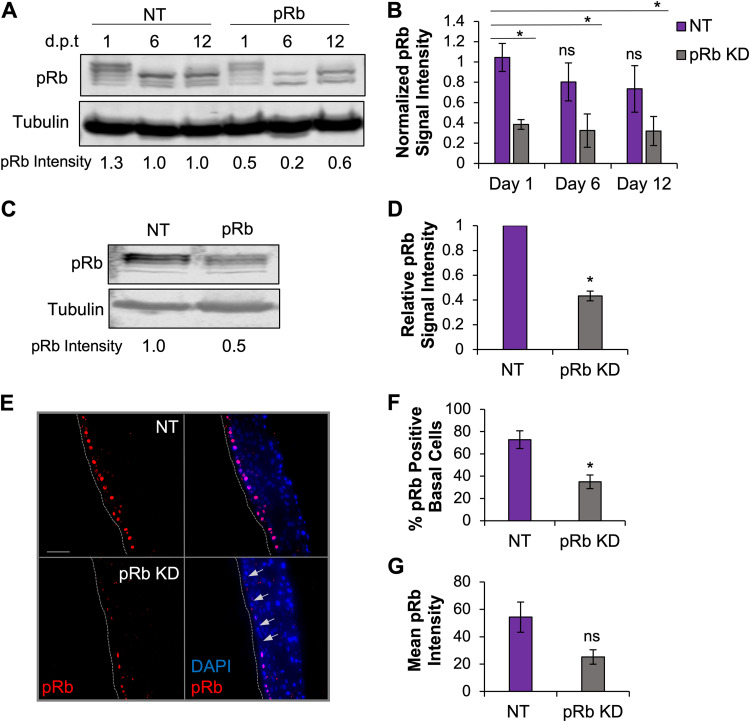

Partial pRb KD was maintained in epithelial raft culture.

Previously, we reported that HPV16 E7 inhibited EBV replication in organotypic raft culture (32). Although E7 is known to interact with a number of cellular regulators, E7 binding and facilitated degradation of the Rb family of pocket proteins is a critical interaction for HPV replication. Here, we explored whether the inhibition of EBV replication by HPV16 E7 could be phenocopied by loss of pRb in differentiated epithelia. We transfected human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT)-immortalized normal oral keratinocytes (NOKs) with siRNA specific to pRb and nontarget (NT) controls. Transfected keratinocytes were then grown in organotypic raft culture (57). EBV infection was established through coculture with EBV-positive Akata BL at day 4 after lifting cells to the air-liquid interface. Infected epithelial tissues were harvested 7 days postinfection, which is 11 days total in raft culture. To confirm if pRb KD would persist for the duration of raft culture, pRb KD efficiency was evaluated in keratinocytes cultured in monolayer for 12 days after siRNA transfection (Fig. 1A). Protein lysates were harvested on the day of raft seeding (day 1), the day of EBV infection (day 6), and 1 day after the day of raft harvest (day 12) (Fig. 1A). We confirmed that a pRb KD of approximately 66% was maintained for 12 days in the monolayer (Fig. 1B). pRb KD in cells on day 1 of raft culture was also confirmed by Western blotting of pRb/p105 protein levels (Fig. 1C). On average, siRNA transfection resulted in 50% pRb KD compared to that of NT controls (Fig. 1D). pRb KD was also evaluated via immunofluorescence (IF) in tissues harvested at the end of raft culture (Fig. 1E). A 50% reduction in the percentage of pRb-positive cells in the basal layer of epithelial tissue and a 50% reduction in pRb mean fluorescence intensity per cell were observed (Fig. 1F and G). Together, these data indicate that a partial pRb KD was maintained for the duration of raft culture.

FIG 1.

pRb knockdown (KD) was maintained in raft culture. (A) NOKs were transfected with siRNAs targeting pRb and scrambled (NT) controls and grown in monolayer culture. Protein lysates were harvested 1, 6, and 12 days post-siRNA transfection (dpt), and pRb knockdown efficiency was examined by Western blotting. A representative Western blot is shown. (B) Quantification of pRb signal intensity from 3 independent siRNA transfections. pRb signal intensity was normalized to tubulin and compared to that of an NT control from day 1, arbitrarily set to 1. (C) NOKs to be used in raft culture were transfected with siRNAs targeting pRb and NT. Protein lysates were harvested 16 to 24 h after siRNA transfection, and pRb knockdown efficiency was examined by Western blotting. A representative Western blot is shown. (D) Quantification of pRb signal intensity from 4 independent siRNA transfections. pRb signal intensity was normalized to tubulin and compared to that of NT controls, arbitrarily set to 1. (E) Immunofluorescence analysis of pRb (red) and nuclear stain DAPI (blue) in raft tissues. Gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer. Scale bars, 50 μm. Arrows depict DAPI-positive basal cells with reduced pRb. (F) pRb-positive basal cells were quantified as a percentage of DAPI-positive cells. (G) Mean pRb fluorescence intensity in the basal layer was calculated as the sum of the pRb mean pixel intensity divided by the number of DAPI-positive cells. Three rafts generated from siRNA-independent transfections were analyzed; six images per raft were quantified using ImageJ. Mean values are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls; ns, no statistical significance.

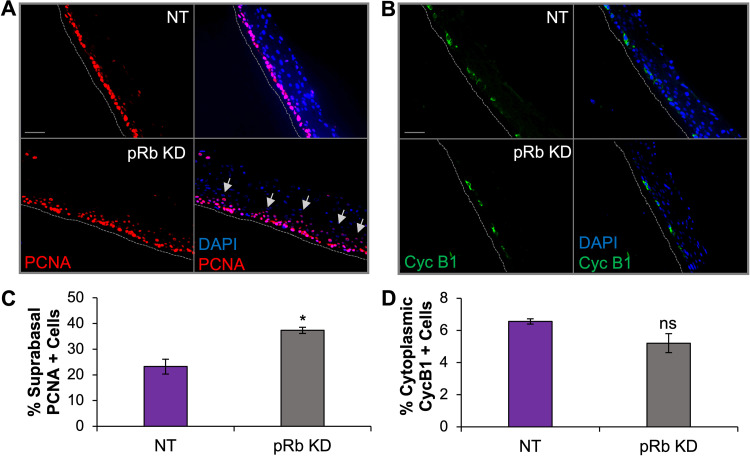

Enhanced S-phase progression was evident in suprabasal epithelial cells as a functional readout for partial loss of pRb in raft tissues.

Cell cycle reentry and progression to S phase can be achieved in postmitotic cells via loss of pRb, as evident by HPV16 E7-facilitated degradation of pRb and the observed unscheduled S-phase entry in keratinocytes normally proceeding through terminal differentiation (58–60). To determine if the partial loss of pRb promoted cell cycle progression in our tissues, we examined the cell cycle markers proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and cyclin B1 (Cyc B1), which served as markers for S phase and G2, respectively. The number of PCNA-positive cells was significantly higher in the suprabasal layers of pRb KD rafts than in the NT controls, indicative of S-phase progression in postmitotic keratinocytes (Fig. 2A and C). No significant change was observed in the number of cells positive for cytoplasmic cyclin B1 after pRb KD (Fig. 2B and D). Thus, while a functional effect after pRb KD with an accumulation of suprabasal cells in S phase was observed, pRb KD alone did not lead to an accumulation of cells in G2.

FIG 2.

Increased S-phase progression in suprabasal cells is evident in raft tissue with partial pRb KD. NOK raft tissues were immunostained to detect PCNA, an S-phase marker, or cytoplasmic cyclin B1, a G2 cell cycle marker. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis of PCNA (red signal). (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of cyclin B1 (Cyc B1, green signal). The nuclear stain DAPI is shown in blue. Scale bars, 50 μm. Gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer of tissue. Gray arrows indicate elevated PCNA in suprabasal layers. (C) Nuclear PCNA was quantified as a percentage of DAPI-positive cells in suprabasal layers. (D) Cytoplasmic cyclin B1 was quantified as a percentage of the total DAPI-positive cells. Three independent rafts from independent siRNA transfections were analyzed. Six images per raft were quantified using ImageJ. Mean values are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls; ns, no statistical significance.

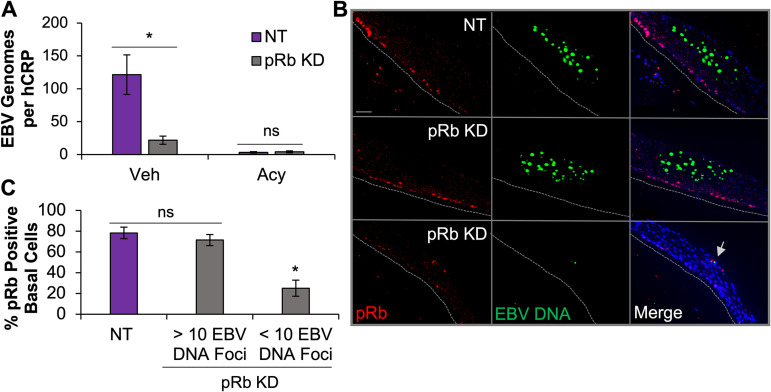

pRb was required for EBV replication in differentiated epithelia.

To establish the effects of depleting pRb on the EBV life cycle in differentiated epithelia, we evaluated EBV replication in our pRb KD rafts. To measure EBV replication, we used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to quantify the number of EBV genomes per cellular DNA control human c-reactive protein gene (hCRP). We found that the number of EBV genomes was significantly lower after pRb KD than in NT controls (Fig. 3A). Treatment with acyclovir, a nucleoside analog that selectively inhibits EBV DNA replication, reduced the number of EBV genomes per cellular DNA in rafts, supporting that the variation in EBV DNA levels in vehicle NT and pRb KD rafts reflected decreased DNA replication and not differences in infectivity between rafts.

FIG 3.

Loss of pRb inhibits EBV replication after de novo infection. (A) The relative EBV genome copy number per DNA copy (human C-reactive protein [hCRP]) was determined using qPCR in NOKs transfected with NT siRNA (NT, n = 5) or siRNA specific to pRb (n = 7). Acyclovir (Acy) treatment was used to block EBV replication and control for infectivity (NT, n = 6, and pRb, n = 6). Veh, vehicle. (B) EBV DNA in raft tissue was visualized using DNAscope followed by immunofluorescence analysis for pRb. Gray dotted lines indicate the tissue basal layer. Scale bars, 50 μm. A gray arrow indicates reduced EBV DNA foci. (C) Nuclear pRb-positive cells were quantified as a percentage of DAPI-positive cells in the basal layer of raft tissue from NT rafts and pRb KD rafts (n = 2). Data from pRb KD rafts were divided into regions with >10 or <10 EBV DNA foci. A minimum of two images per raft were quantified for NT and pRb KD rafts from regions with <10 EBV DNA foci. One to two images were quantified for pRb KD rafts with >10 EBV DNA foci based on availability. Mean values are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for four (A) and two (C) independent siRNA transfections. *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls; ns, no statistical significance.

To corroborate the qPCR findings, DNAscope was used to visualize EBV DNA replication in our raft tissues. DNAscope is a sensitive and specific in situ assay that can detect limited copies of DNA and be combined with immunostaining to visualize both target DNA and protein in tissue. We used a combination of DNAscope and immunofluorescence analysis to evaluate EBV DNA and pRb protein levels in our raft tissues. In the NT control rafts, we observed large patches of tissue positive for EBV DNA, on average 40 EBV DNA foci per patch (Fig. 3B and C). pRb was detected in the basal cells whereas EBV replication was in the upper epithelial layers, and the signals did not appear to overlap. In the pRb KD rafts, we observed two distinct types of DNA patches that correlated with the effectiveness of pRb KD. Large patches of tissue positive for >10 EBV DNA foci, similar to what was observed in the NT control rafts, were detected in tissue areas where basal pRb levels were present. In contrast, tissue areas with low pRb levels in the basal layer correlated with <10 EBV DNA foci per patch (Fig. 3B and C). These data support the observation that pRb is required for EBV replication in differentiated epithelial cells.

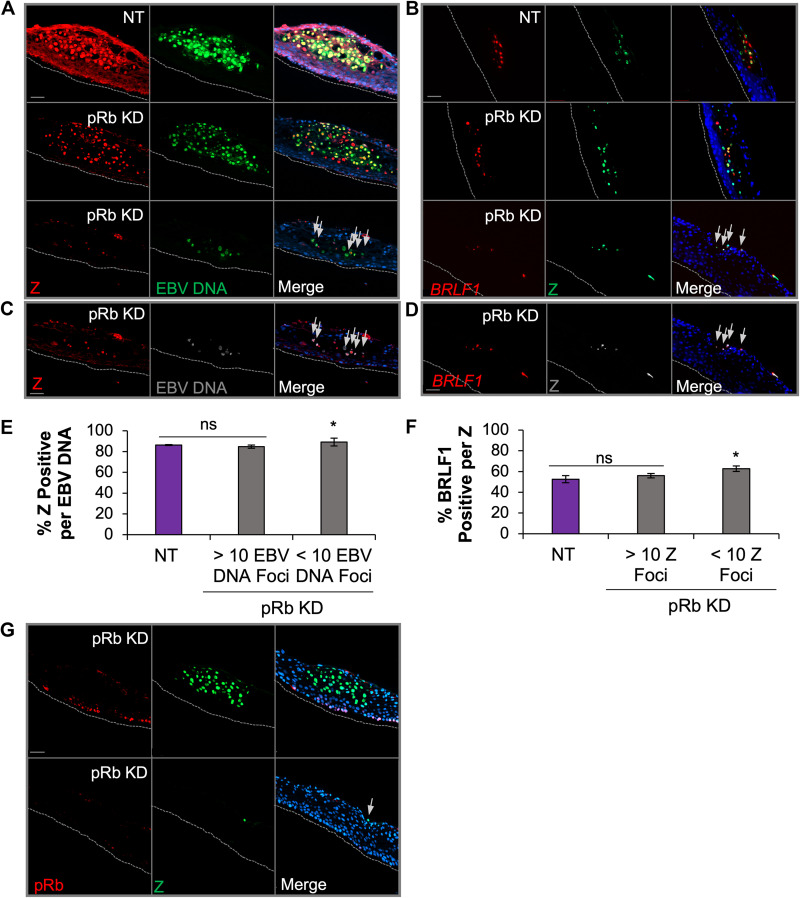

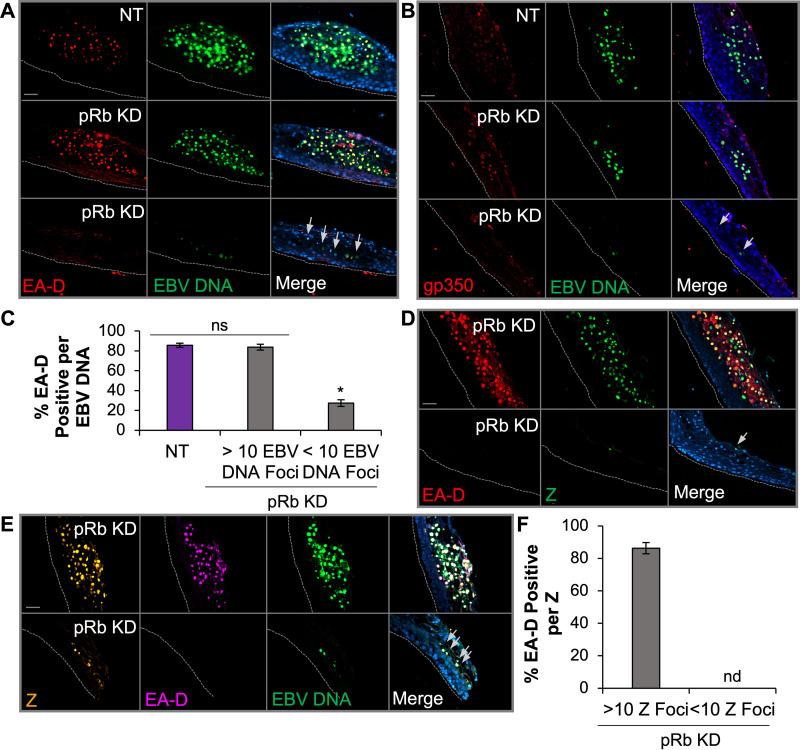

Loss of pRb restricted EBV early and late gene expression despite detection of EBV IE gene products in de novo-infected epithelial rafts.

To determine if the block in EBV replication was related to inhibition of EBV lytic gene expression, DNAscope was used to visualize EBV DNA and immunofluorescence for viral proteins. Analysis of BZLF1 (Z protein), an IE transactivator involved in initiating the cascade of lytic gene expression, revealed that approximately 85% of Z signals colocalized to EBV DNA foci in NT rafts (Fig. 4A, C, and E). Similar to NT rafts, large patches of EBV DNA in pRb KD rafts also showed that at least 85% of the EBV DNA foci were positive for Z. In contrast, tissue areas in the pRb KD rafts with <10 EBV DNA foci per patch showed reduced Z levels, as indicated by the diminished fluorescence intensity. However, when correlating the number of Z-positive EBV DNA foci, we observed that patches with <10 EBV DNA foci were just as likely to be positive for Z as those observed in NT controls and areas of pRb KD rafts with >10 EBV DNA foci per patch (Fig. 4E).

FIG 4.

EBV IE gene expression is not dependent on pRb in raft tissues. (A) DNAscope for EBV DNA (green) was followed by immunofluorescence for Z (red) in NT and pRb KD rafts. (B) RNAscope for BRLF1 RNA (red) was followed by immunofluorescence for Z (green) in NT and pRb KD rafts. The nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 is shown in blue. Arrows in the merged image indicate foci positive for EBV DNA and Z (A and C) or BRLF1 and Z (B and D). (C) Enhanced exposure of the bottom panel in panel A showing Z signal (red) and EBV DNA foci (gray) in pRb KD. (D) Enhanced exposure of the bottom panel in panel B showing R (red) and Z (gray) colocalization pRb KD. (E) The percentage of Z positive per EBV DNA focus was manually counted. (F) Percentage of BRLF1 RNA signal per Z-positive (pos) focus. NT siRNA and pRb KD rafts with <10 EBV DNA foci were quantified from three biologically independent rafts with a minimum of three images per raft analyzed. Areas with >10 EBV DNA foci in pRb KD tissue were quantified from one to two images per raft from two biologically independent rafts. Mean values are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls; ns, no statistical significance. (G) Representative images are shown for detection of Z (green) and pRb (red) in pRb KD raft tissues. Gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer of the tissue. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To analyze the expression of the BRLF1 IE gene product, we employed in situ RNA hybridization (RNAscope) combined with Z immunofluorescence analysis. We were unable to directly visualize EBV DNA and R protein, as several antibodies against the R protein appeared to lack specificity in our tissue staining. Instead, we colocalized BRLF1 RNA with Z protein. Remarkably, detection of Z protein showed a 50% overlap with BRLF1 RNA in both NT and pRb KD rafts in areas with pRb and active EBV replication (Fig. 4B, D, and F). A reduced fluorescence intensity was observed for Z and BRLF1 RNA in areas with <10 EBV DNA signals, which likely reflects the reduced EBV copy number in areas previously shown to correlate with loss of pRb in the basal layer. Furthermore, immunostaining for Z and pRb protein in pRb KD rafts showed that Z was detected despite loss of basal layer pRb (Fig. 4G). Thus, detection of Z and BRLF1, together with the high correlation of Z expression with EBV DNA in areas where EBV replication was reduced, suggests that expression of IE gene transactivators from individual EBV genomes is not dependent on pRb.

Next, we assessed expression of the early viral processivity factor EA-D by using the combination of DNAscope and immunofluorescence analysis. EA-D was detected in tissue areas with large patches positive for EBV DNA in both NT and pRb KD rafts, with at least 85% of EA-D signals colocalizing to EBV DNA foci (Fig. 5A and C). In contrast, areas of tissue with reduced EBV DNA in pRb KD rafts had significantly fewer EA-D-positive signals per EBV DNA, with only 27% of EBV DNA foci being positive for EA-D (Fig. 5A and C). Comparable results were also observed for a late marker of the EBV lytic cycle, gp350, which was not detected in EBV DNA-positive cells in areas of the raft with effective pRb KD (Fig. 5B). To ensure that the loss in EA-D expression was not due to DNAscope signal quenching, sequential immunofluorescence for EA-D and Z was performed starting with the EA-D monoclonal antibody (Fig. 5D and F). A second EA-D monoclonal antibody (Millipore MAB8186) was used, as it showed less background signal. Quantitation of EA-D colocalizing with Z protein in pRb KD rafts detected no EA-D in areas with <10 Z-positive signals (Fig. 5F). Tissue areas with >10 Z-positive signals in pRb KD rafts showed at least 80% copositivity between EA-D and Z signals (Fig. 5F). To visualize Z, EA-D, and EBV DNA simultaneously, we performed DNAscope followed by sequential immunofluorescence for Z and EA-D (Fig. 5E). Further confirming our previous results, we found Z in the absence of EA-D colocalized with areas of tissue with <10 EBV DNA foci (Fig. 5E). Together, these data demonstrate that the inhibition of EBV replication due to loss of pRb correlated with a lack of EBV early gene (EA-D) and late gene (gp350) expression. Thus, these data suggest that pRb is required for early gene expression and progression of the EBV lytic cycle in differentiated epithelia.

FIG 5.

pRb was required for production of EBV early and late genes in differentiated epithelia. (A) DNAscope of EBV DNA followed by immunofluorescence of EA-D (Capricorn no. EBV-018-48180). (B) DNAscope of EBV DNA followed by immunofluorescence of gp350 in rafts. The nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 is shown in blue. Arrows depict EBV DNA foci negative for EA-D (A, D, and E) or gp350 (B). (C) Quantification of EBV DNA foci positive for EA-D in rafts. Images were manually quantified as a percentage of EA-D-positive EBV DNA foci from 3 biologically independent rafts. NT siRNA and regions with <10 EBV DNA foci were quantified from a minimum of three images per raft. Regions with >10 EBV DNA foci were quantified from 1 to 2 images per raft. *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls; ns, no statistical significance. (D) Sequential immunofluorescence of EA-D (Sigma-Aldrich no. MAB8186) followed by Z. (E) Sequential immunofluorescence of Z and then EA-D, followed by DNAscope of EBV DNA. Gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer of tissue. Scale bars, 50 μm. (F) Percentage of Z- and EA-D-positive foci from sequential immunofluorescence (D). Mean values were manually quantified from 2 biologically independent rafts from a minimum of three images per raft. Mean values with error bars representing the standard error of the mean are shown. nd, no detection of EA-D in 10 Z-positive foci.

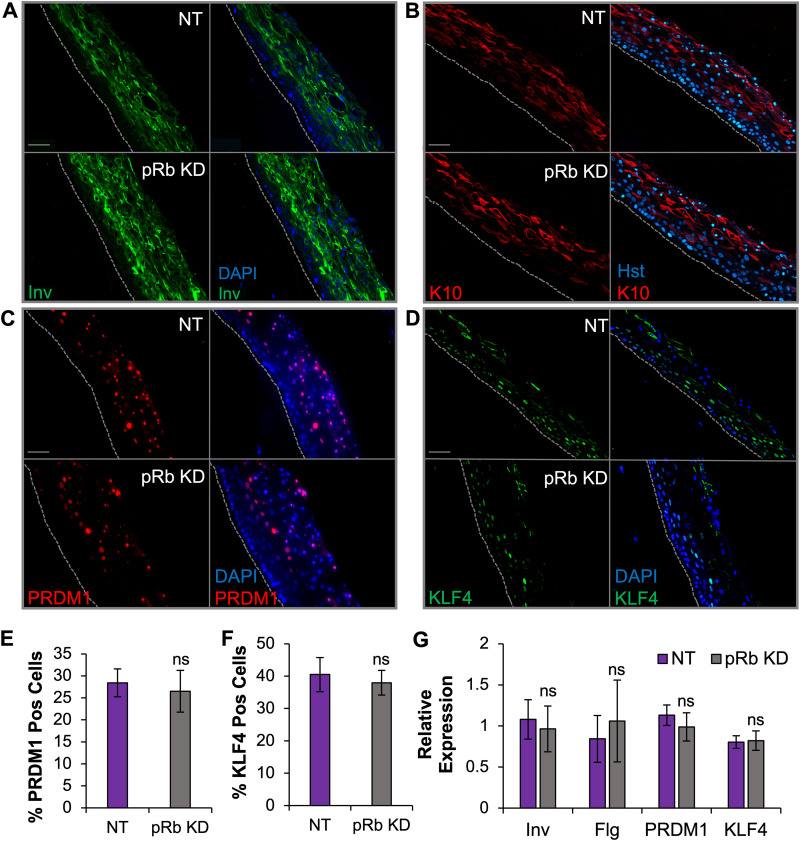

Similar levels of epithelial differentiation markers were observed after pRb KD.

Loss of pRb has been associated with defects in differentiation in cell lines and mouse models (42, 61–65). As EBV replication is associated with terminal differentiation, we examined whether defects in epithelial differentiation in pRb KD rafts would explain the EBV replication defect upon loss of pRb. We first evaluated the levels of KLF4 and PRDM1, cellular transcription factors known to be required for expression of EBV IE genes (19, 20). Using immunofluorescence analysis, we observed no change in the percentage of KLF4- or PRDM1-positive cells in pRb KD rafts compared that of controls (Fig. 6C to F). These results lend further support that pRb is not required for EBV IE gene expression (Fig. 4). Furthermore, there were no observable changes in the levels of early differentiation markers involucrin (Fig. 6A) and cytokeratin 10 (K10) (Fig. 6B). The RNA levels of KLF4, PRDM1, involucrin, and a late terminal differentiation marker, filaggrin, also showed no significant difference in expression after pRb KD (Fig. 6G). Histologically, pRb knockdown and NT tissues also appeared to produce similar stratified tissues (Fig. 7D). Together, these data suggest that partial loss of pRb did not elicit a major deficit in differentiation in our epithelial tissue.

FIG 6.

Differentiation markers following pRb KD were comparable to those of NT controls. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed to examine the following: involucrin (Inv) (A), cytokeratin 10 (K10) (B), PRDM1 (C), and KLF4 (D). Tissue nuclei (blue) were visualized with DAPI or Hoechst 33342 (Hst). Scale bars, 50 μm. Gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer of tissue. (E and F) Quantification of total PRDM1 (E) and KLF4 (F). Positive cells were quantified as a percentage of total DAPI-positive cells from three biologically independent rafts with six images analyzed per raft. (G) The mRNA expression levels of Inv, filaggrin (Flg), PRDM1, and KLF4 were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Marker expression was normalized to cyclophilin and compared to that of an NT raft arbitrarily set to 1. The mean relative expression is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean from a minimum of 5 rafts per group. ns, no statistical significance relative to the NT control.

FIG 7.

Raft tissues with partial loss of pRb did not influence p16 levels or activation of the DNA damage response. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on raft tissues as follows: γH2AX in rafts from NOKs transfected with NT or pRb siRNAs (KD) (A); γH2AX in rafts from human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) immortalized with HPV16 E6E7 (B). Scale bars, 50 μm. Gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer of tissue. (C) Percentage of γH2AX- positive cells in NOK raft tissue (n = 4). γH2AX signal was quantified as a percentage of DAPI- or Hoechst 33342 (Hst)-positive cells using six images per raft. The mean percentage is shown, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean. ns, no statistical significance relative to the NT control. (D) Immunohistochemistry evaluating p16 levels in NOKs and HPV16 E6E7-positive HFK raft tissue. Scale bars, 100 μm. Black dotted lines indicate the basal layer of tissue.

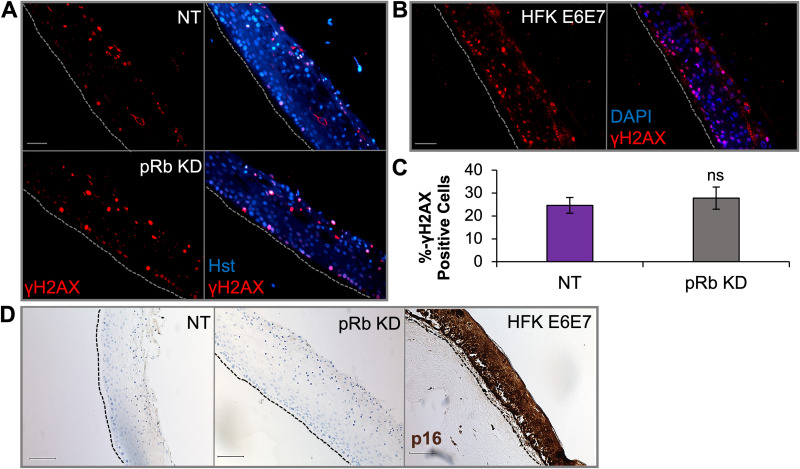

pRb knockdown did not enhance γH2AX focus formation or p16 activation as observed in HPV16 E6E7 rafts.

Aberrant cell cycle progression has been shown to result in replication stress and chromosomal instability, which lead to the activation of the DNA damage response (DDR) (66–69). EBV infection and lytic replication have also been shown to induce the DDR. Activated ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM), a serine/threonine kinase and major DDR transducer recruited to areas with double-strand DNA breaks, is required for EBV replication (70–72). As loss of pRb facilitated an increase in S-phase progression, we examined whether an alteration in the DDR would explain the lack of EBV replication in pRb KD rafts. The levels of γH2AX, a marker for activated ATM, was examined using immunofluorescence. While expression of HPV16 oncogenes E6 and E7 leads to a positive γH2AX signal observed throughout raft tissues, consistent with previous reports, we did not observe any alteration in γH2AX levels after pRb KD compared to that in controls (Fig. 7A to C).

A hallmark of HPV-positive tissue and expression of E7 is the upregulation of p16, a tumor suppressor and CDK inhibitor which functions to inactivate cyclin/CDK complexes that phosphorylate pRb (73, 74). As increased S-phase progression following pRb KD localized to suprabasal cells, we examined whether p16 was increased to control cell proliferation in differentiated tissues. In pRb KD rafts, no increase in p16 levels was observed (Fig. 7D). In contrast, p16 levels were elevated throughout HPV16 E6E7-positive rafts (Fig. 7D). Together, these data suggest that EBV replication inhibition after partial loss of pRb was not due to aberrant activation of the DDR or p16.

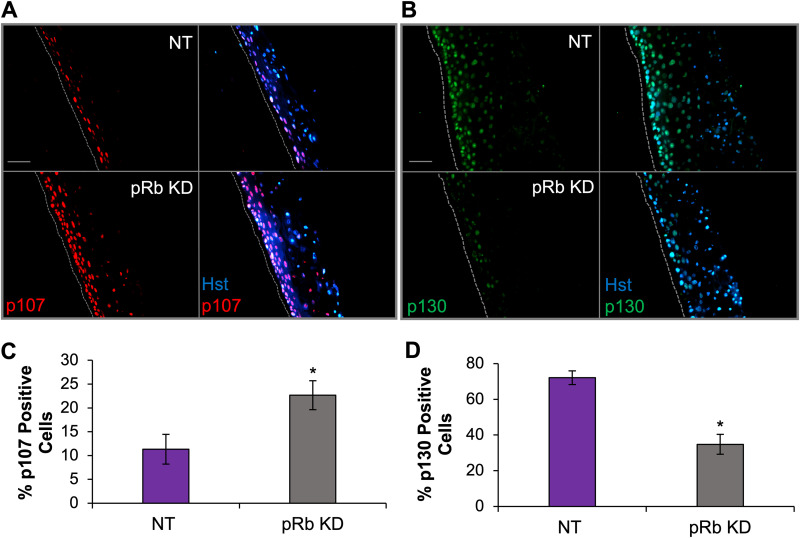

p107 was upregulated while p130 was diminished in pRb KD rafts.

Previous studies have shown that loss of pRb is associated with altered activities of other pocket proteins to enforce cell cycle progression and exit (75, 76). With loss of pRb showing increased S-phase markers restricted to the suprabasal layers without a major deficit in epithelial differentiation, we examined p107 and p130 levels, as these retinoblastoma pocket proteins can have compensatory activities with pRb (75–78). We observed that the number of p107-positive cells increased while the number of p130-positive cells significantly decreased after pRb KD (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with previous reports of pocket protein expression levels during S-phase progression, as hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of pRb during S-phase progression result in upregulation of p107 levels and downregulation of p130 levels (35, 79–81). Together, these data suggest that the restriction of EBV replication following loss of pRb may also involve deregulated expression of the other pocket proteins (p107 and p130) and unscheduled S-phase entry induced by loss of pRb in differentiated epithelia.

FIG 8.

Retinoblastoma pocket proteins, p107 and p130, are deregulated following pRb knockdown. Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on the following NOK-derived raft tissues: p107 (A) and p130 (B). Scale bars, 50 μm; gray dotted lines indicate the basal layer of tissue. (C and D) The number of positive cells in raft tissues was quantified for p107 (C) and p130 (D) and is represented as the percentage of the total Hoechst 33342 (Hst)-positive cells. The average percentages from two (C) and three (D) biologically independent rafts are shown, with a minimum of three images captured per raft. The mean percentage is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean. *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls.

pRb was required for efficient EBV lytic DNA replication in Akata Burkitt lymphoma cells.

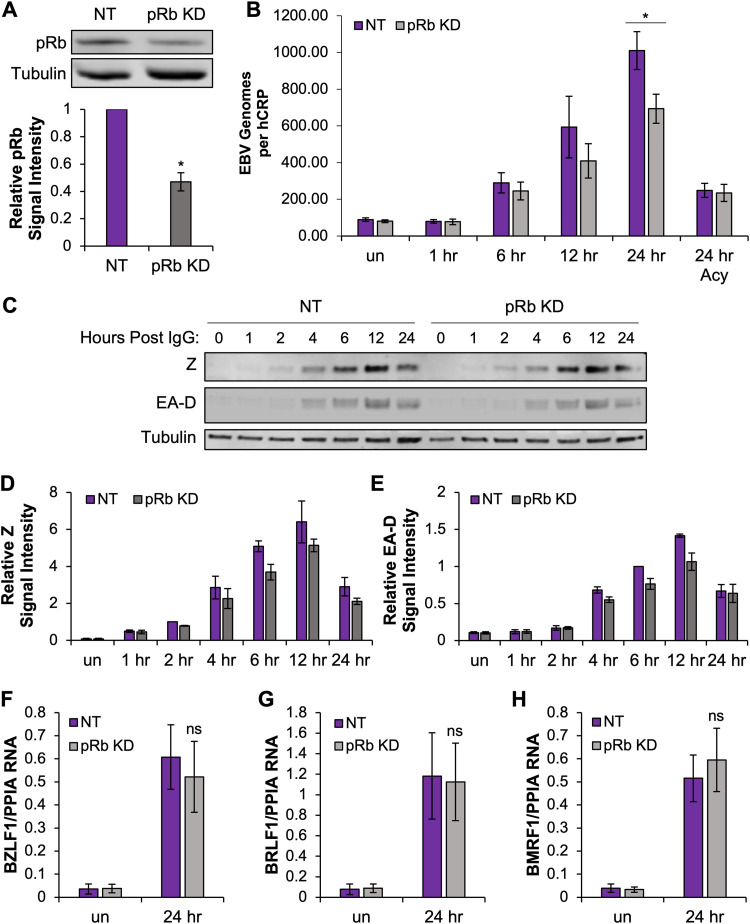

To determine if pRb was required for EBV reactivation from latency, as was observed for de novo infection of differentiated epithelial cells, we used the latently infected Akata Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cell line that carries the same recombinant virus (Akata BX1) used for infection of the epithelial rafts. This Akata BL cell line can be efficiently reactivated from latency by cross-linking the B cell receptor, with up to 95% of cells being reactivated, and allows us to investigate the mechanisms behind the requirement for pRb in EBV lytic replication. Transfection of siRNAs in Akata BL resulted in a 50% knockdown in pRb protein levels (Fig. 9A). Twenty-four hours post transfection, cells were treated with anti-human IgG to cross-link the B cell receptor and induce EBV lytic replication. EBV DNA levels were measured at various intervals. Despite the partial knockdown, pRb KD reduced EBV DNA levels at 12 and 24 hours compared to that in NT controls (Fig. 9B). Acyclovir-treated controls showed a reduced number of EBV genomes at 24 h after IgG treatment with no significant difference between pRb knockdown and NT controls (Fig. 9B). The lower number of EBV genomes in the acyclovir-treated controls measures the expected reduction in EBV replication following treatment. However, the EBV DNA levels were higher in the acyclovir-treated group than in uninduced cells as electroporation induced some cells to reactivate. We next explored if loss of pRb in Akata BL interfered with EBV early gene expression similar to what was observed following de novo infection of differentiated epithelial cells. Interestingly, pRb KD did not significantly affect expression of EBV IE genes or the early gene EA-D (Fig. 9C to H). Protein levels of Z and EA-D appeared sufficient to induce EBV replication (Fig. 9C). Although densitometric analysis of Z and EA-D protein levels following pRb KD showed a slight reduction compared to that of NT controls; the small change was not statistically significant (Fig. 9D and E).

FIG 9.

pRb KD reduces EBV DNA levels following reactivation of Akata BL. (A) Akata BX1 BL cells were electroporated with siRNAs targeting pRb and scrambled siRNA NT controls. Protein lysates were harvested 24 h after siRNA transfection, and pRb KD efficiency was examined by Western blotting. A representative Western blot is shown. Densitometric quantification of pRb signal intensity from 6 independent siRNA transfections was used to measure the pRb KD efficiency. pRb signal intensity was normalized to tubulin and compared to that of an NT control, arbitrarily set to 1. *, P < 0.05. (B) At 24 h posttransfection, cells were treated with 50 μg/mL human anti-IgG antibody to cross-link the B cell receptor and induce EBV reactivation. DNA was collected at 1, 6, 12, and 24 h postinduction. The relative EBV genome copy number per DNA copy (human C-reactive protein [hCRP]) was determined using qPCR in cells transfected with NT siRNA or siRNA specific to pRb (n = 6). Acyclovir (Acy) treatment was used to block EBV replication and control for induction (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 relative to NT controls. un, uninduced. (C) Protein lysates were harvested at various intervals up to 24 h after IgG treatment and blotted for Z and EA-D. A representative Western blot is shown. (D and E) The signal intensities for Z (D) and EA-D (E) from 3 independent siRNA transfections were normalized to tubulin. The mean from 3 independent siRNA transfections is shown and compared to that of the NT control, arbitrarily set to 1. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 3). RNA was collected prior to induction with 50 μg/mL human anti-IgG antibody and then at 24 h postinduction. (F to H) The mRNA expression levels of BZLF1 (F), BRLF1 (G), and BMRF1 (H) were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Viral gene expression was normalized to cyclophilin (PPIA). The mean relative expression is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (n = 6). ns, no statistical significance relative to the NT control.

Loss of pRb attenuated B cell differentiation and maintained elevated c-Myc levels in reactivating Akata BL.

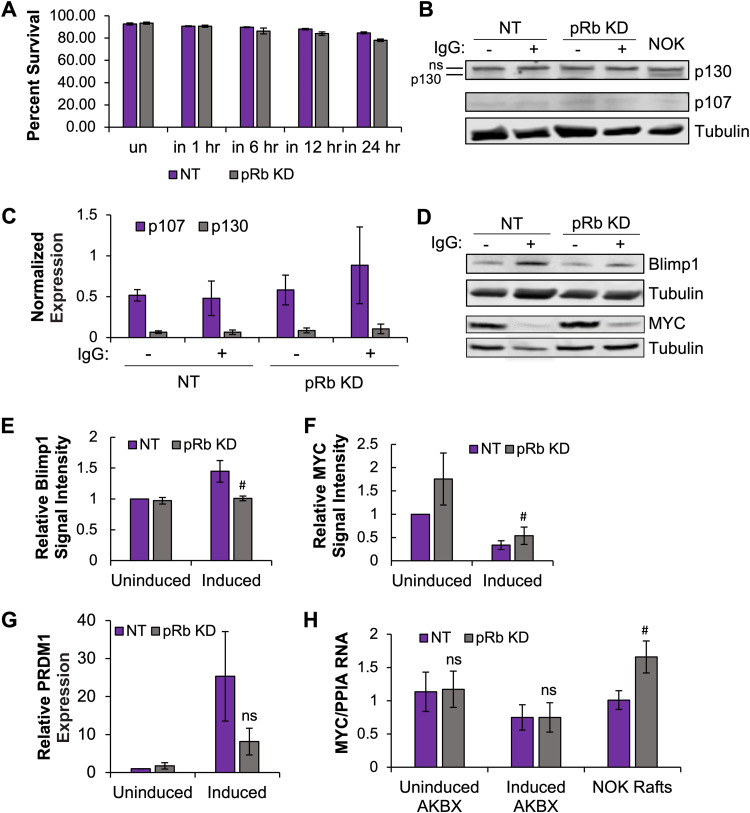

To elucidate how pRb was involved in EBV reactivation, several targets of pRb were studied. First, we examined cell viability following loss of pRb in reactivating Akata BL. Compared to results with NT controls, trypan blue exclusion analysis showed a slight loss in cell viability of about 6% at 24 h following pRb KD (Fig. 10A). However, the slight loss in viability of the pRb KD cells was likely too low to result in the 30% decrease in DNA levels observed (Fig. 9B). B cell differentiation into plasma B cells is a known trigger for EBV reactivation. In the EBV latent state, Akata BL are highly proliferative, but B cell receptor (BCR) cross-linking is a differentiation stimulus that promotes exit from the cell cycle enforced by pRb, p107, and p130. As expected for cycling cells, the level of p107 and p130 was low in latently infected Akata BL (Fig. 10B). Surprisingly, induction of differentiation and EBV reactivation did not change p107 or p130 levels regardless of pRb status (Fig. 10B and C), different from the pRb KD effects on p107 and p130 in epithelial rafts (Fig. 8). Notably, p130 protein was significantly lower in Akata BL than in NOKs (Fig. 9B). In BL, alterations in p130/RBL2 that have been observed include mutations and a restricted cytoplasmic cellular localization (82). As EBV can undergo efficient lytic replication in Akata BL, whether p130 is required for EBV replication in either differentiated epithelium or BL cells is unclear. With unchanged p130 and p107 levels, we next examined whether loss of pRb attenuated the differentiation response. PRDM1/Blimp1 is a cellular transcription factor that is expressed when B cells undergo terminal differentiation to plasmablasts. Akata BL induced to reactivate EBV showed a 40% decrease in PRDM1/Blimp1 protein, supporting a statistical trend for loss of pRb in attenuating B cell differentiation upon BCR cross-linking (Fig. 10D and E). A 3-fold decrease in RNA abundance in pRb KD cells compared to that in NT controls was also observed (Fig. 10G); however, this change did not reach statistical significance. Several confounding factors may contribute to variability following electroporation of siRNAs into Akata BL: (i) electroporation alone stimulated EBV reactivation prior to siRNA KD taking effect and (ii) differences in the efficiency of pRb KD also contributed to the variability in our assays.

FIG 10.

Loss of pRb attenuated B cell differentiation following EBV reactivation in Akata BL. Akata BX1 BL cells were transfected with siRNAs targeting pRb (pRb KD) and scrambled siRNA NT controls and then 24 h posttransfection were induced with 50 μg/mL human anti-IgG antibody. (A) Cells were stained with trypan blue at various intervals, and the percentage of live cells is shown (n = 3). NT and pRb KD protein lysates were harvested prior to induction (un) and various intervals up to 24 h postinduction (in). (B) A representative Western blot for p130 and p107 is shown. (C) The mRNA expression for p130 and p107 was analyzed by RT-qPCR and normalized to cyclophilin (PPIA). The average normalized expression relative to cyclophilin is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (n = 3). (D) A representative Western blot for PRDM1/Blimp1 and c-Myc is shown. Protein levels were measured by densitometric analysis for (E) PRDM1/Blimp1 and c-Myc (F). The signal intensity from 3 to 4 independent siRNA transfections was normalized to tubulin and compared to values of the uninduced NT control, arbitrarily set to 1. The average is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (n = 3 for PRDM1/Blimp1 [P < 0.1]; n = 4 for c-Myc [P < 0.08]). (G) PRDM1/Blimp1 RNA levels were normalized to cyclophilin and compared to that of uninduced NT cells, arbitrarily set to 1. The average is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (n = 6). (H) c-Myc RNA levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR. RNA levels were normalized to PPIA (cyclophilin). The average ratio of MYC to PPIA RNA is shown, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (n = 6 for Akata [AKBX] BL, n = 3 for NOK epithelial rafts [P < 0.06]). #, P < 0.1; ns, no statistical significance relative to the NT control.

The requirement of pRb for B cell differentiation was not observed in the NOK rafts, suggesting that the distinct roles of pRb in promoting EBV replication in differentiated epithelium and BL are dependent on the cellular context. Burkitt lymphoma is characterized by a hallmark chromosomal translocation that places c-Myc in the immunoglobulin locus that results in c-Myc overexpression (83, 84). Myc has been shown to regulate the latent-lytic switch of EBV by binding to the lytic origin of DNA replication, OriLyt, and blocking DNA looping to the BZLF1 promoter (85). Upon lytic reactivation, c-Myc protein is depleted to allow BZLF1 binding to OriLyt and initiation of lytic DNA replication (27, 85). Analysis of c-Myc expression in Akata BL showed loss of c-Myc at 24 h after induction of reactivation compared to uninduced cells (Fig. 10D and F). However, pRb KD showed a 2-fold increase in c-Myc protein levels in uninduced cells compared to NT controls that remained 40% elevated 24 hours after induction of EBV reactivation (Fig. 10D and F). Consistent with the attenuation in differentiation, pRb KD cells induced to reactivation showed a 40% increase in c-Myc protein levels, but levels did not reach statistical significance. c-Myc RNA levels were not affected by loss of pRb (Fig. 10H). However, partial pRb KD in NOK epithelial rafts showed a 1.6-fold increase in RNA levels. Overall, our results support a global role for pRb in EBV lytic replication in both differentiated epithelium and BL cells. Although variability existed in the reactivation of EBV in Akata BL, statistical trends suggested that the inhibitory effect of pRb loss on EBV replication was related to attenuation of B cell differentiation and maintenance of c-Myc protein levels. How pRb regulates EBV replication in differentiated epithelium may be distinct and still needs to be defined.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that de novo EBV infection of HPV16-immortalized keratinocytes grown in organotypic raft culture inhibited EBV replication and that HPV16 E7 was sufficient to inhibit EBV replication (32). As E7 facilitates the degradation of pRb, we questioned whether EBV required pRb for viral replication in differentiated epithelia. To address this question, we evaluated the EBV life cycle in organotypic rafts grown using an hTERT-immortalized oral keratinocyte cell line (NOK) transfected with siRNAs to deplete pRb. pRb KD efficiency ranged from 50 to 66%, with partial KD lasting for the duration of organotypic raft culture (Fig. 1). These results are consistent with previous reports that have also successfully used siRNA technology to knock down a protein of interest in raft culture (86). We were also able to achieve a 50% pRb KD in Akata BL (Fig. 9A). Results from qPCR analysis from organotypic raft tissues and Akata BL demonstrated a reduction in the number of EBV genomes in pRb KD compared to that in controls (Fig. 3A and 9B). Treatment with acyclovir showed comparable levels of infection between NT and pRb KD rafts and confirmed activation of EBV lytic DNA replication in vehicle NT controls (Fig. 3A and 9B). These data support a global requirement of pRb in EBV lytic DNA replication.

DNA viruses have evolved mechanisms to inactivate pRb and promote S-phase entry for efficient viral replication. Herpesviruses, including EBV, encode several viral factors that interact with pRb. EBV R, but not Z, binds to pRb (51). The EBV protein kinase BGLF4 also phosphorylates pRb without affecting E2F1 levels (53). Conflicting evidence also suggests that forced expression of R can induce S-phase entry and increased E2F1 levels, required for S-phase gene expression (87). E2F1 has also been shown to be required for transactivation of the EBV DNA polymerase gene (88). On the other hand, functions of pRb appear to be required for herpesvirus replication. Overexpression of EBV Z and R can result in a G1 cell cycle arrest, consistent with previous reports that EBV replication occurs in the absence of cellular DNA synthesis (53–55). In quiescent cells, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) expressing HPV E7 partially rescued viral titers in the absence of the protein kinase UL97, but a growth deficit was still evident (89). Notably, pRb KD prior to infection with human cytomegalovirus resulted in an inhibition of viral DNA replication without affecting IE gene expression (90). In the present study, loss of pRb had no effect on the expression of the EBV IE BZLF1 and BRLF1 genes from individual genomes in differentiated epithelial cells. Expression of the early gene product, EA-D, and the late gene product, gp350, was significantly inhibited in areas where basal pRb was lost. Inhibition of gp350 likely resulted from the block in DNA replication, as late gene expression depends on viral replication (91). Interestingly, in the context of HPV-immortalized raft tissues, we also noted that IE gene expression was preserved, while BMRF1 (EA-D) and BALF2 early gene expression was inhibited (32). In Akata BL, activation of EBV lytic gene expression, including IE and BMRF1 gene expression was not significantly affected and suggest a different mechanism for pRb in EBV reactivation (Fig. 5 and 9). Expression of the late gene marker, gp350, was not examined in Akata BL. These studies indicate that IE gene expression was not dependent on pRb. However, in the context of differentiated epithelial cells, loss of pRb may interfere with the transactivator functions of R and/or Z, affecting early gene expression and production of viral replicative factors for replication or Z binding to OriLyt for initiation of DNA replication. Future studies aim to determine if pRb is required for EBV R and/or Z transactivator function in differentiated epithelial cells.

A prior study establishing EBV infection of epithelial rafts showed that as early as 2 days postinfection, EBV replication, determined by detection of Z protein, was observed in the upper layers of the epithelium that spread downward into the stratum spinosum (17). It is yet unclear if EBV infects and replicates in the basal layer of the epithelial raft (17). In our epithelial raft infection model, EBV infection was initiated from the apical surface and replicated in the upper differentiated layers. However, in our study, nuclear pRb expression appeared restricted to the basal layer (Fig. 1). A second anti-pRb antibody (Origene) showed nuclear pRb signals in the basal and suprabasal layers, as previously reported (data not shown) (92, 93). However, nuclear pRb signal did not appear to reach the upper differentiated layers, where EBV replication occurred. As we infected rafts on day 4 after lifting, it is possible that EBV may come in contact early in infection with pRb-positive suprabasal cells, which get pushed into the upper layers. Alternatively, pRb-dependent cellular changes that occur during epithelial differentiation are required for EBV replication. Indeed, loss of pRb stimulated S-phase progression in postmitotic keratinocytes, as indicated by the observed increase in suprabasal PCNA-positive cells and altered expression of p107 and p130 pocket proteins in our epithelial rafts (Fig. 2A and 8A and B) (94, 95).

Pocket proteins are critical for control of cell cycle progression and cellular differentiation. Deregulation of pocket protein expression has been associated with aberrant cell cycle progression and delays in differentiation. As cellular differentiation is a key trigger to induce EBV reactivation and replication, we were surprised that epithelial differentiation was not altered after pRb KD, as indicated by similar levels of KLF4- and PRDM1/Blimp1-positive cells in epithelial rafts (Fig. 6). We also identified no alterations in activation of γH2AX or p16. As we achieved a partial pRb KD in tissues, the expression of pRb in some cells could support epithelial differentiation. Alternatively, p107 and p130 have been shown to compensate for the loss of pRb and may contribute to the cell cycle exit required for epithelial differentiation (75–77). p107 and p130 enforce cellular quiescence by forming repressive complexes that inhibit E2F activity through interactions with other MuvB protein complexes that form the DREAM complex (96). It is possible that available pools of p107 and p130 contribute to the cell cycle exit, promote epithelial differentiation, and limit the activation of γH2AX and p16 in pRb KD rafts. The increase in p107 after pRb KD in the epithelial rafts would suggest that increased p107 may enforce cell cycle exit in the suprabasal cells in the absence of pRb, while loss of p130 levels may destabilize E2F levels and disrupt the repressive DREAM complex, enabling the observed S-phase progression in suprabasal keratinocytes. Intriguingly, p130 is expressed in the upper differentiated layers initially infected by EBV, suggesting that p130 may facilitate EBV replication early in the lytic cycle after de novo infection of the epithelia. While it remains unclear if inactivation of p107 and p130 is required for EBV replication following de novo infection, the EBV-encoded protein kinase, EBV-PK, has been shown to phosphorylate both p107 and p130 following overexpression in an osteosarcoma cell line (97). In addition, HCMV and herpes simplex virus 1 have been reported to require p130, but not p107 in the case of HCMV, for viral replication (90, 97, 98). As HPV E7 facilitates the degradation of pRb, p107, and p130 to promote S-phase entry in postmitotic keratinocytes and delay epithelial differentiation (60, 92, 99), future studies will explore whether p130 or p107 is required for EBV replication.

Our studies with the Akata BL cell line suggest that the cellular context can influence the mechanism of pRb regulation of EBV lytic replication. pRb KD in Akata BL resulted in a decrease in EBV DNA levels following induction of viral reactivation compared to those in NT controls (Fig. 9B). However, loss of pRb did not appear to affect lytic viral gene expression (Fig. 9). Instead, pRb was required for the efficient B cell differentiation noted by the decreased expression of PRDM1/Blimp1 in pRb KD BL cells induced for viral reactivation (Fig. 10D), which was not observed following pRb KD in epithelial rafts (Fig. 6). A slight elevation in c-Myc protein levels also suggests a direct interference with BZL1 activation of OriLyt for initiation of DNA replication. Cross talk between c-Myc and pRb has been observed, where c-Myc can also control S-phase progression in the absence of pRb (100, 101). C-Myc and E2F1 can also interfere with BZLF1 transactivator activity to explain the inhibitory effects of pRb loss on EBV lytic replication (102). Whether inhibition of EBV replication in differentiated epithelium is related to c-Myc needs to be further studied. It is known that p107, which is upregulated following loss of pRb in differentiated epithelium, directly interacts with c-Myc to repress Myc transactivator activity and S-phase progression (103). We previously showed increased Myc RNA levels in HPV E6E7 immortalized rafts similar to what we observed upon pRb KD in epithelial rafts (Fig. 10H) (32). However, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) treatment, which should suppress Myc activity and activate BZLF1 expression, of HPV E6E7 immortalized rafts did not rescue EBV replication despite a decrease in Myc RNA levels (32). It may be interesting to examine whether the elevated p107 levels following loss of pRb in differentiated epithelia restrict c-Myc to initiate EBV lytic replication.

Together, our data demonstrate a role for pRb in EBV lytic replication after de novo infection of the epithelia and in reactivation from latency in EBV-positive BL. Although pRb is required for EBV early gene expression and replication in differentiated epithelia, the functions of pRb that are required for viral lytic replication and reactivation remain unclear. In BL, pRb was required for efficient terminal differentiation and depletion of c-Myc. In both cell types, EBV IE genes were expressed but IE transactivator activity may be restricted by factors downstream of pRb. In BL, one such factor appeared to be c-Myc. The observation that EBV replicates in the absence of host DNA replication may suggest that repressive complexes, like the retinoblastoma pocket proteins, are needed to restrict host DNA replication in G1/early S phase, such that stimulation of S-phase progression would interfere with EBV replication. Similarly, in vitro EBV infection of cycling cells tends to result in latent infections. It will be interesting to explore and define the cell cycle gene expression states, which are deregulated in cancer, that coordinate latency and viral replication. In sum, this study provides novel insight into cellular factors required for EBV replication after de novo infection in the epithelia and identify pRb as an important factor that explains how HPV E7 inhibits EBV replication in copositive epithelia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

hTERT-immortalized normal oral keratinocytes (NOKs; gifted by Karl Munger [104]) were maintained in 1× keratinocyte serum-free medium (Gibco no. 10724-011) supplemented with human recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF) and bovine pituitary extract (Gibco no. 37000-015). For siRNA transfection of NOKs, cells were seeded at 1.2 × 106 cells per 100-mm by 20-mm dish. The following day, NOKs were transfected with 10 nM siRNA (Dharmacon no. D-003296-05-0020) and 5 μL/mL of DharmaFECT transfection reagent 1 (Dharmacon no. T-2001-03) in 6 mL of transfection medium for 5 h. For transfection medium, 20 nM siRNA, DharmaFECT transfection reagent, and Opti-MEM medium (Gibco no. 31985-070) were combined to a final volume of 3 mL and incubated on ice for 20 min. The mixture was then combined with 3 mL of growth medium for each 100-mm dish. After the 5-h incubation, transfection medium was replaced with growth medium. Cells were incubated overnight and seeded on collagen plugs (see “Organotypic raft culture”). The Akata BX1 Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cell line was grown in 1× RPMI medium (Corning no. 10-040-CV) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Akata BX1 BL cells were induced in 1× RPM1 medium supplemented with 1% FBS and 100 μg/mL goat anti-human IgG antibody for 24 to 48 h. NIH 3T3 mouse J2 fibroblasts were propagated in 1× Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Corning no. 10-013-CV) supplemented with 10% calf serum. All cell lines were maintained in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2, incubator. For siRNA transfection of Akata BX1 cells, the Invitrogen Neon electroporation system was used. A total of 1 × 106 cells were washed two times with prewarmed 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 100 μL of resuspension buffer R with 500 nM siRNA. The cell/siRNA suspension was drawn into the Neon pipette tip and electroporated at 1,375 V for 10 ms with 3 pulses. Electroporated cells were dispensed into 2 mL of prewarmed 1× RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS for a final concentration of siRNA at 25 nM. Cells were allowed to recover for 24 h and then induced with 50 μg/mL AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment goat anti-human IgG (H+L) antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 1 to 24 h.

Organotypic raft culture.

Organotypic rafts were generated as previously described with the following modifications (32, 56, 105). Briefly, 6.25 × 105 3T3 fibroblasts were embedded on ice in a 2.5-mL collagen mixture comprising 80% rat tail collagen type 1 (Corning no. 354236), 10% reconstitution buffer (0.05 M NaOH, 2.2% sodium bicarbonate, 4.8% HEPES), 10% 10× Hams F-12, and 0.24% 1 N NaOH. A 2.5-mL volume of the collagen mixture containing fibroblasts was added to a 6-well dish and incubated overnight in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2, incubator. Following the overnight incubation, the plugs were equilibrated with 1 mL of supplemented keratinocyte serum-free medium (KSFM) for approximately 10 min at room temperature. After equilibration, 2 × 106 NOKs were seeded in 1 mL of supplemented KSFM into each plug and incubated overnight. The following day, the plugs were washed with 1× PBS, lifted onto a stainless-steel grid, and fed below with E-medium supplemented with 5% FBS and 10 μM C8 (Santa Cruz no. 202397). The medium was changed every 48 h. At 4 days postlifting, rafts were scored with a sterile razor blade and 2.5 × 106 induced Akata BX1 cells resuspended in 200 μL of 1× PBS were added dropwise to the apical surface of the raft and incubated for approximately 10 min at room temperature before replacement of the growth medium. Rafts treated with acyclovir received 100 μg/mL acyclovir (Sigma no. A4669) added to the growth medium following Akata BX-1 inoculum incubation. At 7 days postinfection, the rafts were harvested for further analysis. Tissues were stored at −20°C prior to DNA isolation or frozen at −80°C prior to RNA isolation. Tissues harvested for immunofluorescence/DNAscope were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. Tissues were then washed three times with 1× PBS for 15 min at 4°C and stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C prior to tissue processing and paraffin embedding.

Western blotting.

Approximately 1 × 106 NOKs were lysed in 1× NuPAGE buffer (25% 4× NuPAGE buffer [Invitrogen no. NP0007], 1% 100× protease inhibitor cocktail [ThermoFisher no. 1860932], 1% 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 1% 100× phosphatase inhibitor 2 [Sigma no. P5726], 1% 100× phosphatase inhibitor 3 [Sigma no. P0044], 10% 1 M dithiothreitol [DTT], and 61% autoclaved water). Approximately 0.3 × 106 Akata BX1 BL cells were lysed in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (25% RIPA buffer, 1% 100 mM PMSF, 1% 100× phosphatase inhibitor 2 [Sigma no. P5726], 1% 100× phosphatase inhibitor 3 [Sigma no. P0044], 10% 1 M DTT, 1% 100× Halt protease inhibitor cocktail [Thermo Scientific no. 1861278], 60% autoclaved water). Protein lysates were denatured by incubation at 70 to 95°C for 3 to 10 min and placed on ice. Equal volumes of each sample were loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gels and run for 3 h at 90 V. Proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon no. IPFL00010) for 1 h 30 min at 100 V. Blocking and antibody incubations were performed using Odyssey Intercept blocking buffer as previously described (106). Primary antibodies at a 1:1,000 dilution were used for pRb (Santa Cruz no. sc-102), β-tubulin (LiCor no. C80827-01), PCNA (Santa Cruz no. sc-56), p107 (Santa Cruz no. sc-250), p130 (Sigma-Aldrich no. HPA019703), Blimp1/PRDM1 (Cell Signaling no. 9115), cMYC (Cell Signaling no. 139875), BZLF1 (Santa Cruz no. sc-53904), and EA-D (Sigma-Aldrich no. MAB8186). After washing, membranes were incubated with a 1:15,000 dilution of LI-COR secondary antibodies. Membranes were washed four times in 1× Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST). Membranes were stored in 1× TBS and imaged using an Odyssey infrared imaging system and quantified using Image Studio.

qPCR analysis.

EBV DNA levels were quantified using qPCR as described previously (32). Briefly, DNA was isolated using the QIAamp blood minikit (Qiagen no. 51106). Serial dilutions of DNA isolated from the EBV-positive Namalwa cell line were used for standard curve analysis. For reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-PCR) analysis, RNA was purified and treated with TURBO DNase (Invitrogen no. AM1907) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated using the LunaScript RT supermix kit (NEB no. E3010L). Serial dilutions of cDNA generated from EBV-negative rafts or induced Akata BX1 cells were used for standard curve analysis. All qPCRs were performed using a 7500 FAST Applied Biosystems thermocycler, with reaction mixtures containing 10 ng of DNA or 50 ng of cDNA, 300 nM concentrations of forward and reverse primers, 200 nM probe (for TaqMan), nuclease-free water, and TaqMan universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems no. 4304437) or Luna Universal qPCR master mix (NEB no. M3003E) in a 15-μL reaction mixture. For primer sequences, see Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in PCR

| Gene name | Sequence (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| EBV BHRF1 | F: CGTGTGCATGGAAATGGTACC |

| R: CGAAAGGCGGAGAGGTGTT | |

| Probe: TGCATCCTGTGTTGGAGCTAGCAGCA | |

| hCRP | F: CTTGACCAGCCTCTCTCATGC |

| R: TGCAGTCTTAGACCCCACCC | |

| Probe: TTTGGCCAGACAGGTAAGGGCCACC | |

| KLF4 | F: CGAACCCACACAGGTGAGAA |

| R: TACGGTAGTGCCTGGTCAGTTC | |

| PRDM1/Blimp1 | F: TACATACCAAAGGGCACACG |

| R: TGAAGCTTCCCTCTGGAATA | |

| Involucrin | F: TCCTCCAGTCAATACCCATCAG |

| R: CAGCAGTCATGTGCTTTTCCT | |

| Filaggrin | F: TGAAGCCTATGACACCACTGA |

| R: TCCCCTACGCTTTCTTGTCCT | |

| PPIA | F: CCTGGGCCGCGTCTCC |

| R: GCAGGAACCCTTATAACCAAATCC | |

| BZLF1 | F: TTGGGCACATCTGCTTCAACAGGA |

| R: AATGCCGGGCCAAGTTTAAGCAAC | |

| BRLF1 | F: AATCTCCACACTCCCGGCTGTAAA |

| R: TGGCTTGGAAGACTTTCTGAGGCT | |

| BMRF1 | F: CAGGCTGAGGAACGAGCAG |

| R: CAACGAGGAAGCCGTCTTG | |

| cMYC | F: CGTTCTCACACATCAGCACAA |

| R: CACTGTCCAACTTGACCCTCTTG | |

| RBL1 (p107) | F: TGCCAATGTCTCCTCTAATGC |

| R: AGTCTTCTCTTAGCACTCCCT | |

| RBL2 (p130) | F: GTGACTGAAGTTCGTGCTGA |

| R: GCTGTACCTATCGTATAATGTGGT |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (32). Briefly, 5-μm tissue sections on charged glass slides (VWR no. 48311-703) were baked for 2 h at 60°C and cooled to room temperature for 30 min prior to staining. Deparaffinized tissue sections in xylene were hydrated with a decreasing ethanol gradient (100% to 50%). Antigen retrieval in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and 0.05% Tween 20 was performed using a pressure cooker for 9 min. Slides were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 45 min at room temperature and incubated with blocking buffer (5% bovine serum albumin [BSA] in 1× PBS) for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Primary antibody was added to 2.5% BSA in 1× PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Primary antibodies used include antibodies specific for pRb (1:25, BD Pharmingen no. 554136), involucrin (1:100, Santa Cruz no. sc-28557), K10 (1:50, Santa Cruz no. sc-52318), KLF4 (1:100, Sigma no. HPA002926), PRDM1 (1:50, Cell Signaling no. 9115), PCNA (1:300, Santa Cruz no. sc-56), cyclin B1 (1:100, Abcam no. 32053), p107 (1:50, Santa Cruz no. sc-250), and p130 (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich no. HPA019703). Tissue sections were extensively washed and incubated with secondary antibodies (Invitrogen no. A11029, A11032, A11034, and A11058) diluted 1:1,000 in 1× PBS for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified chamber. For sequential staining, slides were incubated with a poly-horseradish peroxidase (poly-HRP)-conjugated antibody (Invitrogen no. B40961) for 1 h at 37°C after the first primary antibody incubation. Tissues were then incubated with Opal dyes (Akoya no. FP1495001KT) or tyramide-488 (Invitrogen no. B40953) for 10 min at room temperature and protected from light. Antigen retrieval was then performed using a pressure cooker for 15 min with the buffer previously outlined. After cooling for 20 min, the slides were incubated with blocking buffer and a second primary antibody as previously described. Following the second primary antibody incubation, tissues were incubated with the poly-HRP antibody and Opal dyes as mentioned above. Tissues were mounted with ProLong diamond antifade mountant with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Invitrogen no. P36962). For slides stained with Hoechst, a 1:1,000 dilution of Hoechst (Thermo Fisher no. 62249) was added at the time of secondary antibody or Opal dye incubation and mounted with Invitrogen ProLong glass antifade mountant (no. P36980). Slides were imaged on a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 inverted fluorescence microscope in the Research Core Microscopy Imaging Core at LSU Health Shreveport. Images were equally brightened with ImageJ. For quantification, images were manually quantified or quantified with ImageJ when indicated.

DNAscope/RNAscope.

DNAscope was performed as previously described with minor modifications (107). Following RNase denaturation, tissue sections were denatured in 70% formamide at 76°C for 3 min. Slides were then washed with water, and denatured probes were added to tissues and incubated for 15 min at 60°C in a humidified chamber and transferred to 40°C for overnight hybridization. Probes used were specific for EBV BARF1 (ACDBio no. 485371) and Bacillus subtilis dapB, a negative control (ACDBio no. 310043). The next day, slides were washed with 0.5× wash buffer (ACDBio no. 310091) and amplification and detection were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ACDBio). For subsequent immunofluorescence staining, slides were blocked for 45 min in 5% goat serum, primary antibody was added in 2.5% goat serum, and slides were incubated overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Primary antibodies used include antibodies specific for pRb (1:25, BD Pharmingen no. 554136), BZLF1 (1:200, Santa Cruz no. sc-53904), and EA-D (1:10, Capricorn no. EBV-108-48180 or Sigma-Aldrich no. MAB8186). Following overnight incubation, tissues were incubated with a poly-HRP antibody and Opal dyes (Akoya no. FP1488001KT and FP1496001KT), mounted, imaged, and analyzed as described for immunofluorescence staining. For sequential immunofluorescence staining following DNAscope, after secondary and Opal dye incubation following the first antibody incubation, tissues were steamed in a pressure cooker in target retrieval reagent (ACDBio no. 322000) for 15 min and incubated with HRP blocker for 15 min at 40°C. Subsequent blocking and incubation with primary antibody, secondary antibody, and Opal dyes were performed as previously described.

The RNAscope procedure was performed as previously described, with RNase A incubation omitted (107). After protease plus treatment, slides were incubated with a prewarmed probe specific for BRLF1 (ACDBio no. 1153831-Cl) for 2 h at 40°C and incubated with fluorescent detection reagents as indicated in the manufacturer’s protocol (ACDBio). For subsequent immunofluorescence staining, slides were washed with TBST wash buffer and blocked for 30 min at room temperature in 10% goat serum in TBS–1% BSA. Primary antibody was then diluted in TBS–1% BSA and incubated overnight in a humidified chamber. The next day, the slides were rinsed in TBST wash buffer and incubated with a poly-HRP secondary antibody for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, tissues were incubated with Opal dyes, dried, mounted, imaged, and analyzed as previously described.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed from raft tissues generated from biologically independent siRNA transfections. For most analyses, data were averaged from a minimum of 3 images per raft and a minimum of 3 rafts per group and as indicated in the figure legends. P values were calculated using Student's t test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jianfeng Liu and Corey Gemelli for support in tissue processing and staining, Ellen Friday for RNA extraction, Joseph Tod Guidry and the LSU Health Shreveport Research Core Facility Microscopy Imaging Core for technical input and support.

This research was supported by NIH grant no. R01 R01DE025565 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research to R.S.S., grant no. R01AI118904 from the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases to J.M.B., and grant no. R01CA211576 from the National Cancer Institute to M.S., by CoBRE grant no. P30GM110703 (Center for Molecular and Tumor Virology) and P20GM134974 (Center for Applied Immunology and Pathological Processes) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and by a Carroll Feist predoctoral fellowship from the LSU Health-Shreveport Feist-Weiller Cancer Center to J.E.M.

Contributor Information

Rona S. Scott, Email: rona.scott@lsuhs.edu.

Lawrence Banks, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen JI. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med 343:481–492. 10.1056/NEJM200008173430707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niedobitek G, Meru N, Delecluse HJ. 2001. Epstein-Barr virus infection and human malignancies. Int J Exp Pathol 82:149–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu JL, Glaser SL. 2000. Epstein-Barr virus-associated malignancies: epidemiologic patterns and etiologic implications. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 34:27–53. 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao SW, Tsang CM, Lo KW. 2017. Epstein-Barr virus infection and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 372:20160270. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady G, Macarthur GJ, Farrell PJ. 2008. Epstein-Barr virus and Burkitt lymphoma. Postgrad Med J 84:372–377. 10.1136/jcp.2007.047977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, Kuhle J, Mina MJ, Leng Y, Elledge SJ, Niebuhr DW, Scher AI, Munger KL, Ascherio A. 2022. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 375:296–301. 10.1126/science.abj8222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanz TV, Brewer RC, Ho PP, Moon JS, Jude KM, Fernandez D, Fernandes RA, Gomez AM, Nadj GS, Bartley CM, Schubert RD, Hawes IA, Vazquez SE, Iyer M, Zuchero JB, Teegen B, Dunn JE, Lock CB, Kipp LB, Cotham VC, Ueberheide BM, Aftab BT, Anderson MS, DeRisi JL, Wilson MR, Bashford-Rogers RJM, Platten M, Garcia KC, Steinman L, Robinson WH. 2022. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 603:321–327. 10.1038/s41586-022-04432-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pathmanathan R, Prasad U, Chandrika G, Sadler R, Flynn K, Raab-Traub N. 1995. Undifferentiated, nonkeratinizing, and squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Variants of Epstein-Barr virus-infected neoplasia. Am J Pathol 146:1355–1367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei KR, Xu Y, Liu J, Zhang WJ, Liang ZH. 2011. Histopathological classification of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 12:1141–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young LS, Dawson CW. 2014. Epstein-Barr virus and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Chin J Cancer 33:581–590. 10.5732/cjc.014.10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji MF, Wang DK, Yu YL, Guo YQ, Liang JS, Cheng WM, Zong YS, Chan KH, Ng SP, Wei WI, Chua DT, Sham JS, Ng MH. 2007. Sustained elevation of Epstein-Barr virus antibody levels preceding clinical onset of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 96:623–630. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao SM, Liu Z, Jia WH, Huang QH, Liu Q, Guo X, Huang TB, Ye W, Hong MH. 2011. Fluctuations of Epstein-Barr virus serological antibodies and risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective screening study with a 20-year follow-up. PLoS One 6:e19100. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henle W, Ho HC, Henle G, Kwan HC. 1973. Antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus-related antigens in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Comparison of active cases with long-term survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 51:361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coghill AE, Hildesheim A. 2014. Epstein-Barr virus antibodies and the risk of associated malignancies: review of the literature. Am J Epidemiol 180:687–695. 10.1093/aje/kwu176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reusch JA, Nawandar DM, Wright KL, Kenney SC, Mertz JE. 2015. Cellular differentiation regulator BLIMP1 induces Epstein-Barr virus lytic reactivation in epithelial and B cells by activating transcription from both the R and Z promoters. J Virol 89:1731–1743. 10.1128/JVI.02781-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laichalk LL, Thorley-Lawson DA. 2005. Terminal differentiation into plasma cells initiates the replicative cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J Virol 79:1296–1307. 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1296-1307.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Temple RM, Zhu J, Budgeon L, Christensen ND, Meyers C, Sample CE. 2014. Efficient replication of Epstein-Barr virus in stratified epithelium in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:16544–16549. 10.1073/pnas.1400818111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li QX, Young LS, Niedobitek G, Dawson CW, Birkenbach M, Wang F, Rickinson AB. 1992. Epstein-Barr virus infection and replication in a human epithelial cell system. Nature 356:347–350. 10.1038/356347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nawandar DM, Wang A, Makielski K, Lee D, Ma S, Barlow E, Reusch J, Jiang R, Wille CK, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS, Mertz JE, Hutt-Fletcher L, Johannsen EC, Lambert PF, Kenney SC. 2015. Differentiation-dependent KLF4 expression promotes lytic Epstein-Barr virus infection in epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005195. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai DL, Li X, Wang L, Xie C, Jin Y, Zeng MS, Zuo Z, Xia TL. 2021. Identification of an N6-methyladenosine-mediated positive feedback loop that promotes Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Biol Chem 296:100547. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heilmann AM, Calderwood MA, Portal D, Lu Y, Johannsen E. 2012. Genome-wide analysis of Epstein-Barr virus Rta DNA binding. J Virol 86:5151–5164. 10.1128/JVI.06760-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takada K, Shimizu N, Sakuma S, Ono Y. 1986. trans activation of the latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genome after transfection of the EBV DNA fragment. J Virol 57:1016–1022. 10.1128/JVI.57.3.1016-1022.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zalani S, Holley-Guthrie E, Kenney S. 1996. Epstein-Barr viral latency is disrupted by the immediate-early BRLF1 protein through a cell-specific mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:9194–9199. 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feederle R, Kost M, Baumann M, Janz A, Drouet E, Hammerschmidt W, Delecluse HJ. 2000. The Epstein-Barr virus lytic program is controlled by the co-operative functions of two transactivators. EMBO J 19:3080–3089. 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ragoczy T, Heston L, Miller G. 1998. The Epstein-Barr virus Rta protein activates lytic cycle genes and can disrupt latency in B lymphocytes. J Virol 72:7978–7984. 10.1128/JVI.72.10.7978-7984.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rooney CM, Rowe DT, Ragot T, Farrell PJ. 1989. The spliced BZLF1 gene of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) transactivates an early EBV promoter and induces the virus productive cycle. J Virol 63:3109–3116. 10.1128/JVI.63.7.3109-3116.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schepers A, Pich D, Hammerschmidt W. 1996. Activation of oriLyt, the lytic origin of DNA replication of Epstein-Barr virus, by BZLF1. Virology 220:367–376. 10.1006/viro.1996.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lo KW, Chung GT, To KF. 2012. Deciphering the molecular genetic basis of NPC through molecular, cytogenetic, and epigenetic approaches. Semin Cancer Biol 22:79–86. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsang CM, Yip YL, Lo KW, Deng W, To KF, Hau PM, Lau VM, Takada K, Lui VW, Lung ML, Chen H, Zeng M, Middeldorp JM, Cheung AL, Tsao SW. 2012. Cyclin D1 overexpression supports stable EBV infection in nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:E3473–E3482. 10.1073/pnas.1202637109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsang CM, Deng W, Yip YL, Zeng MS, Lo KW, Tsao SW. 2014. Epstein-Barr virus infection and persistence in nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Chin J Cancer 33:549–555. 10.5732/cjc.014.10169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang R, Ekshyyan O, Moore-Medlin T, Rong X, Nathan S, Gu X, Abreo F, Rosenthal EL, Shi M, Guidry JT, Scott RS, Hutt-Fletcher LM, Nathan CA. 2015. Association between human papilloma virus/Epstein-Barr virus coinfection and oral carcinogenesis. J Oral Pathol Med 44:28–36. 10.1111/jop.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidry JT, Myers JE, Bienkowska-Haba M, Songock WK, Ma X, Shi M, Nathan CO, Bodily JM, Sapp MJ, Scott RS. 2019. Inhibition of Epstein-Barr virus replication in human papillomavirus-immortalized keratinocytes. J Virol 93:e01216-18. 10.1128/JVI.01216-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]