ABSTRACT

Biodesulfurization poses as an ideal replacement to the high cost hydrodesulfurization of the recalcitrant heterocyclic sulfur compounds, such as dibenzothiophene (DBT) and its derivatives. The increasingly stringent limits on fuel sulfur content intensify the need for improved desulfurization biocatalysts, without sacrificing the calorific value of the fuel. Selective sulfur removal in a wide range of biodesulfurization strains, as well as in the model biocatalyst Rhodococcus qingshengii IGTS8, occurs via the 4S metabolic pathway that involves the dszABC operon, which encodes enzymes that catalyze the generation of 2-hydroxybiphenyl and sulfite from DBT. Here, using a homologous recombination process, we generate two recombinant IGTS8 biocatalysts, harboring native or rearranged, nonrepressible desulfurization operons, within the native dsz locus. The alleviation of sulfate-, methionine-, and cysteine-mediated dsz repression is achieved through the exchange of the native promoter Pdsz, with the nonrepressible Pkap1 promoter. The Dsz-mediated desulfurization from DBT was monitored at three growth phases, through HPLC analysis of end product levels. Notably, an 86-fold enhancement of desulfurization activity was documented in the presence of selected repressive sulfur sources for the recombinant biocatalyst harboring a combination of three targeted genetic modifications, namely, a dsz operon rearrangement, a native promoter exchange, and a dszA-dszB overlap removal. In addition, transcript level comparison highlighted the diverse effects of our genetic engineering approaches on dsz mRNA ratios and revealed a gene-specific differential increase in mRNA levels.

IMPORTANCE Rhodococcus is perhaps the most promising biodesulfurization genus and is able to withstand the harsh process conditions of a biphasic biodesulfurization process. In the present work, we constructed an advanced biocatalyst harboring a combination of three genetic modifications, namely, an operon rearrangement, a promoter exchange, and a gene overlap removal. Our homologous recombination approach generated stable biocatalysts that do not require antibiotic addition, while harboring nonrepressible desulfurization operons that present very high biodesulfurization activities and are produced in simple and low-cost media. In addition, transcript level quantification validated the effects of our genetic engineering approaches on recombinant strains’ dsz mRNA ratios and revealed a gene-specific differential increase in mRNA levels. Based on these findings, the present work can pave the way for further strain and process optimization studies that could eventually lead to an economically viable biodesulfurization process.

KEYWORDS: biocatalysis, biodesulfurization, dibenzothiophene, genetic engineering, metabolic engineering, dsz

INTRODUCTION

Biodesulfurization has gained attention over the last several decades, either as an alternative method or a complementary method to the hydrodesulfurization bioprocess for the removal of dibenzothiophene (DBT) derivatives from petroleum products. It takes place, through the intracellular enzymatic action of microbial biocatalysts that functionally express the 4S metabolic pathway (1). Rhodococcus qingshengii IGTS8, previously known as R. erythropolis IGTS8 (2), is probably the most extensively studied desulfurizing Gram-positive bacterium, wherein the desulfurization operon dszABC was discovered for the first time (3). These genes encode a DBT-sulfone monooxygenase (DszA), a 2-hydroxybiphenyl-2-sulfinate (HBPS) desulfinase (DszB), and a DBT monooxygenase (DszC), respectively. DszA and DszB are flavin-dependent enzymes and require the flavin reductase DszD for activity. The highly conserved dszABC operon of R. qingshengii IGTS8 is localized on the 150-kb megaplasmid pSOX, in contrast to the chromosomally localized gene dszD. Notably, plasmid-borne dsz genes have also been reported in other rhodococci (4), but the dszABC operon of Gordonia spp. is located on the bacterial chromosome (5, 6). The enzymatic reactions are sequentially performed by DszC, DszA, and DszB in this order, allowing for the stepwise conversion of DBT to DBTO2, HBPS, and finally, 2-hydroxybiphenyl (2-HBP) (7) (Fig. 1). This selective carbon-sulfur bond cleavage allows for sulfur removal without reducing the calorific value of the fuel (8). Natural desulfurizing biocatalysts reported to date include several species belonging to the genera Achromobacter (9), Brevibacterium (10), Chelatococcus (11), Gordonia (12, 13), Mycobacterium (14), Microbacterium (15), Nocardia (16), Paenibacillus (17, 18), Sphingomonas (19), and Rhodococcus (20–24). Despite the fact that several additional biocatalysts have also been generated via genetic engineering, a commercial biodesulfurization process has not been developed yet for any petroleum product (1). Several known limitations impede the process, many of which are the result of intrinsic properties of the native dsz operon, including the Pdsz promoter repression caused by inorganic sulfate and by the sulfur-containing amino acids l-methionine and l-cysteine (25). Desulfurization activity repression is common in dszABC operons of most desulfurizing strains, including the genera Rhodococcus, Corynebacterium, Gordonia, and Sphingomonas. This repression of biodesulfurization (BDS) activity has been related to the inhibitory effect of readily bioavailable sulfur sources on the production of DBT desulfurization enzymes (19, 25–31). Moreover, a translational coupling caused by gene overlap between the stop codon of dszA and the start codon of dszB, results in reduced expression levels of DszB, the enzyme responsible for the rate-limiting step of the 4S pathway (8, 32). In the native operon of R. erythropolis DS-3, the dszA/dszB/dszC mRNA ratio was shown to be decreasing relative to the gene order, a phenomenon attributed to the correlation of transcriptional levels and gene proximity to the Pdsz promoter. Moreover, the protein levels of DszB were far lower than that of DszC, as indicated by Western blot analysis. Therefore, the deduced lower efficiency of dszB mRNA translation compared to the other two dsz genes is suspected to contribute to the DszB-dependent limitation of biodesulfurization rate (33). Within the scope of overcoming the aforementioned limitations and enhancing biodesulfurization, the genetic manipulations implemented to date include either the removal of the gene overlap between dszA and dszB (34), or a change in the order of dsz genes (33, 35), or expression of the dsz genes under the control of a different promoter (27, 30, 36, 37). Importantly, the optimized gene order has been established as dszBCA, based on the catalytic activities of the enzymes and the order of reactions in the metabolic pathway. Following rearrangement, the ratio of mRNA was changed and the enhanced protein levels of DszB and DszC significantly increased the biodesulfurization capability of the recombinant strain (33).

FIG 1.

4S pathway in Rhodococcus strain IGTS8. A diagram depicting the 150-kb plasmid (pSOX) of wild-type R. qingshengii IGTS8, the dsz mRNA transcript (dszA-dszB-dszC), and the enzymatic background for biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene (DBT) is shown.

For the development of advanced recombinant Rhodococcus strains via genetic engineering, the aforementioned approaches commonly include the utilization of nonintegrative expression vectors or the random integration of nonreplicating suicide vectors (38–42). Although these genome-editing strategies are simple and fast, they are preferably implemented on R. erythropolis dsz-null strains and not native desulfurizing rhodococci, so that an isogenic background is ensured for comparison purposes (33, 43). Importantly, however, more stable genetic changes are required for industrial-scale fermentation, since plasmid instability necessitates antibiotic addition, a practice prohibitive from both an environmental and a sustainability point of view (44).

Notably, in a biphasic system, Gram-positive Rhodococcus cells are advantageous against their Gram-negative desulfurizing counterparts due to the robust hydrophobic cell wall they harbor (45, 46). However, the extremely low amenability of the genus to genetic manipulations in contrast to the model bacteria Escherichia and Pseudomonas spp. renders the generation of recombinant Rhodococcus biocatalysts laborious and time-consuming. The main reason for the challenging nature of targeted genetic manipulations is the low efficiency of RecA-mediated integration compared to the significantly more prominent nonhomologous recombination events (44).

Precise genome editing via a two-step homologous recombination process can introduce unmarked, scarless, and stable modifications in the genome of the biocatalyst. In our previous work, we successfully applied this method for the construction of genetically engineered Rhodococcus strains in an effort to study the metabolic interplay among the transsulfuration and desulfurization pathways (47). Here, using the same methodology, we generate two recombinant strains harboring native or rearranged, nonrepressible desulfurization operons within the native dsz locus of R. qingshengii IGTS8. To mitigate the effect of sulfate repression, we selected the alternative rhodococcal promoter Pkap1, which is not repressed by sulfate and exhibits 2-fold higher activity than that of the 16S rRNA promoter, rrn (30). Importantly, a unique combination of rearrangement of the dsz operon and overlap removal for dszA and dszB, as well as simultaneous promoter exchange, is achieved in the present work. In this way, we monitored the positive effects of both promoter-associated insensitivity to repressive sulfur sources and operon rearrangement in isogenic genetic backgrounds. The genetically engineered strains do not require antibiotic addition and are produced in simple and low-cost media while harboring nonrepressible desulfurization operons that exhibit very high biodesulfurization activities. Thus, we managed to enhance biodesulfurization in the model biocatalyst Rhodococcus strain IGTS8 through targeted editing of the native dsz operon.

RESULTS

Growth and desulfurization of genetically engineered strains in the presence of DBT.

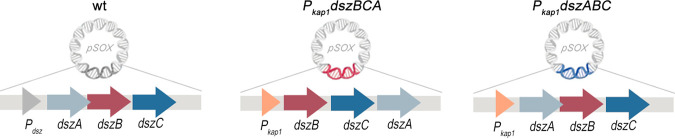

The genetic engineering approaches employed here resulted in the construction of two recombinant biocatalysts that express the dsz genes under the control of the 340-bp kap1 promoter element isolated from R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 (30), either in the regular or in a rearranged order (Fig. 2). First, an in-locus exchange of the native Pdsz promoter with Pkap1 was employed for the generation of a recombinant strain that expresses the native dszABC operon (strain Pkap1-dszABC). In addition, a dszΔ strain lacking the entire promoter and operon region (PdszΔ dszAΔ dszBΔ dszCΔ) was constructed and used for the generation of a second desulfurizing recombinant strain, that harbors a combination of genetic changes integrated in the former dsz locus. These included the rearranged operon dszBCA instead of the native dszABC, a reconstructed ribosome-binding site (RBS) for dszB, and expression under the control of Pkap1 instead of the native Pdsz promoter (strain Pkap1-dszBCA) (Fig. 2; see also Materials and Methods). The RBS for dszB was reconstructed based on the corresponding sequence of dszA RBS. As expected, no biodesulfurization activity was detected for the dszΔ strain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The constructed strains were isogenic, allowing for direct comparison of biodesulfurization activities to the wild-type (wt) IGTS8 strain, since no locus other than dsz was modified. Moreover, the recombinants generated did not require antibiotic addition, as the utilized vector pK18mobsacB was completely excised during the second homologous recombination event (47). To examine the functionality of the newly introduced DNA sequences, wt and recombinant strains of approximately the same initial inoculum size were grown on a synthetic medium (chemically defined medium [CDM]) in the presence of ethanol as the sole carbon source and DBT (0.1 mM) as the sole sulfur source (47) (Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

Organization of dsz loci. A diagram depicting the dsz locus located within the 150-kb plasmid, pSOX, of wild-type R. qingshengii IGTS8 (Pdsz-dszA-dszB-dszC) compared to the same locus of genetically engineered isogenic strains Pkap1-dszBCA and Pkap1-dszABC is shown. Notice the gene overlap between dszA and dszB, which is present only in the native operons.

FIG 3.

Growth and biodesulfurization in the presence of DBT. The growth (biomass, g/L) and desulfurization capability for wt and recombinant strains grown in the presence of 0.1 mM DBT as the sole sulfur source are compared. The calculated growth kinetic parameters are presented in the top left inset (gray = wt, red = Pkap1-dszBCA, and blue = Pkap1-dszABC). The concentrations (μM) of produced 2-HBP and DBTO2 are quantified at four time points (24, 48, 72, and 96 h). Asterisks indicate P values (*, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001; n = 5) for comparison of total concentrations (in μM) of 2-HBP and DBTO2 produced by each strain.

The formation of the 4S-pathway products was monitored by sample collection and measurement of the produced 2-HBP concentration (μM) at four time points (24, 48, 72, and 96 h). Notably, in addition to 2-HBP production, DBTO2 was also detected, validated, and quantified by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Statistical analysis highlighted a significant increase in DBT utilization rate of Pkap1-dszBCA strain compared to the wt strain, evident after 48 h. The Pkap1-dszABC strain also exhibited significantly increased biodesulfurization (after 24 and 48 h) compared to the wt strain. Moreover, for comparative evaluation of growth, the kinetic parameters specific growth rate (μmax) and maximum biomass concentration (Cmax) were calculated through nonlinear fitting of the experimental data to the mathematical growth model (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 3, top left inset). Statistical analysis of the calculated parameters revealed a marginal decrease in μmax and a significant increase in Cmax for the Pkap1-dszBCA strain, compared to the wt strain (P < 0.05), whereas calculated values for the Pkap1-dszABC strain exhibited no significant differences.

Effect of rich culture media on strain growth and biodesulfurization activity.

To assess the insensitivity of the Pkap1 promoter to repressive sulfur sources, all strains were grown in rich culture media such as lysogeny broth (LB) or nutrient broth (NB) without the addition of DBT. The biodesulfurization phenotype was detected with the implementation of desulfurization assays using resting cells collected at three time points, during early, middle, and late log phases of the actively growing cultures (Fig. 4). Recombinant strains exhibited significant desulfurization activity despite the presence of various repressive sulfur sources in the culture medium, in contrast to the wt strain that expresses the dszABC operon under the control of Pdsz promoter (t = 12 h, LB, 0.04 ± 0.01 U/mg dry cell weight [DCW]; t = 12 h, NB, 0.03 ± 0.01 U/mg DCW). The genetic modifications of the Pkap1-dszBCA strain led to maximum catalytic activities of 5.0 ± 0.27 U/mg DCW in LB (t = 12 h) and 4.1 ± 0.24 U/mg DCW in NB (t = 12 h), whereas the Pkap1-dszABC strain produced slightly lower maximum biodesulfurization activities of 3.5 ± 0.12 U/mg DCW (t = 12 h; LB) and 3.3 ± 0.12 U/mg DCW (t = 12 h; NB), respectively. Growth was not affected by the genetic modifications, since the attained specific growth rates and maximum biomass concentrations of the two recombinant strains were not significantly different from those of the wt strain (see Table S1).

FIG 4.

Desulfurization of strains grown in rich culture media. The biomass (g/L) and desulfurization capabilities (units of DBT converted to 2-HBP and DBTO2/mg DCW) for genetically modified Pkap1-dszBCA (red) and Pkap1-dszABC (blue) strains, using either LB or NB as the culture media, are compared to the wt strain (gray). Measurement of desulfurization activity was performed after 6, 12, and 18 h of growth.

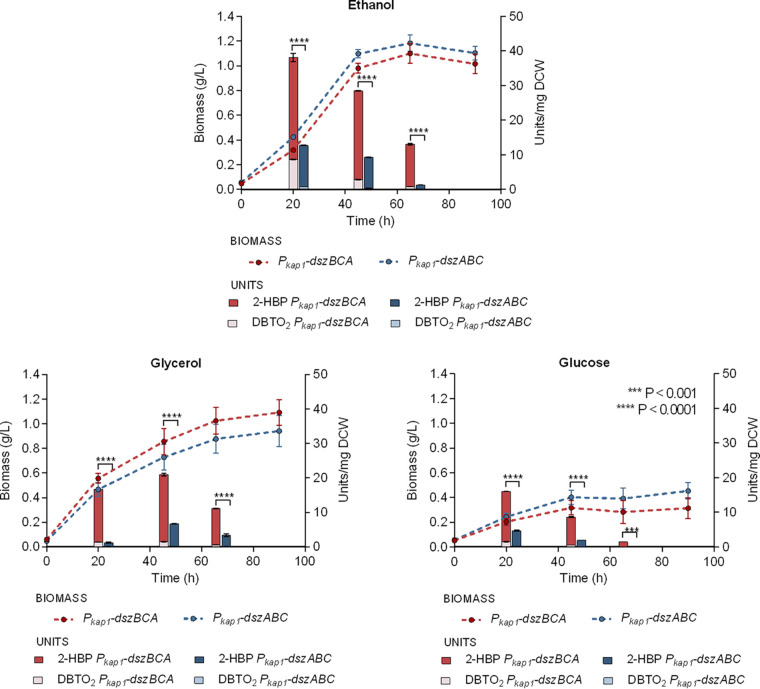

Effect of sulfur sources on strain growth and catalytic activity.

The biodesulfurization activity of the wt strain R. qingshengii IGTS8 is known to be controlled by repressive sulfur sources such as sulfate, methionine, and cysteine (8, 25, 47, 48). However, since the genetically engineered strains were able to desulfurize after growth in rich culture media, we further assessed the individual effect of different sulfur sources on the desulfurization capability of the strains. Rhodococcus cultures were grown on CDM in the presence of ethanol as the sole carbon source, with the supplementation of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), sulfate, l-methionine, or l-cysteine as the sole sulfur source (Fig. 5). Supplementation of DMSO in the culture medium as the sole sulfur source revealed a significant enhancement of biodesulfurization activity for strain Pkap1-dszBCA compared to the wt strain (P < 0.001), while a significant reduction in biodesulfurization was observed when the gene order remained in its native state under the control of Pkap1 for the recombinant Pkap1-dszABC strain (P < 0.01). Importantly, both strains harboring the promoter exchange exhibited remarkable desulfurization in the presence of sulfate compared to the wt strain (Pkap1-dszBCA, 86-fold increase, P < 0.001; Pkap1-dszABC, 24-fold increase, P < 0.01). Methionine or cysteine supplementation as the sole sulfur source in the culture medium resulted in lower overall desulfurization activity, compared to DMSO and sulfate as sole sulfur sources. However, the biodesulfurization phenotype was significantly enhanced for the recombinant strains in comparison to the wt strain, showing an ~10-fold increase for methionine and an up to 40-fold increase for cysteine (Fig. 5 and Table 1). Comparison of calculated growth kinetic parameters for recombinants versus the wt strain did not reveal any statistically significant differences (see Table S2). Importantly, although supplementation of different sulfur sources (0.5 mM sulfur) had no significant effect on growth of each examined strain, biodesulfurization was significantly affected by the choice of sulfur source. DMSO was the preferred sulfur source for all tested strains (wt, P < 0.0001 for DMSO versus sulfate, methionine, and cysteine; Pkap1-dszBCA and Pkap1-dszABC, P < 0.01 for DMSO versus sulfate and P < 0.0001 for DMSO versus methionine and cysteine), followed in order by sulfate (P < 0.01 compared to DMSO), cysteine, and methionine (P < 0.0001 and P < 0.001, respectively, compared to sulfate), for both recombinant strains. Notably, we also confirmed that the wt strain was unable to desulfurize efficiently when sulfate, methionine, or cysteine was provided as sole sulfur source (0.5 mM), whereas DMSO showed no repression of desulfurization in the wt strain.

FIG 5.

Effects of different sulfur sources on growth and biodesulfurization activity. Growth curves (biomass, g/L) and desulfurization capabilities (units of DBT converted to 2-HBP and DBTO2/mg DCW) of wt, Pkap1-dszBCA, and Pkap1-dszABC isogenic strains grown in the presence of 0.5 mM DMSO, sulfate, methionine, or cysteine as the sole sulfur sources are presented. Ethanol was used as the sole carbon source (165 mM). Measurement of desulfurization activity was performed after 20, 45, and 65 h of growth. See also Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Attained biodesulfurization values for strains grown in the presence of different S sources

| Sulfur source and log phase | Mean activity ± the SEMa |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| wt | Pkap1-dszBCA | Pkap1-dszABC | |

| DMSO | |||

| Early | 31.52 ± 0.31 | 47.58 ± 0.82 | 14.73 ± 0.32 |

| Middle | 21.09 ± 0.07 | 38.75 ± 0.73 | 12.07 ± 0.03 |

| Late | 15.25 ± 0.75 | 32.58 ± 0.44 | 8.76 ± 0.04 |

| Sulfate | |||

| Early | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 36.94 ± 0.52 | 10.45 ± 0.57 |

| Middle | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 25.78 ± 0.17 | 6.71 ± 0.14 |

| Late | 0.43 ± 0.07 | 20.33 ± 0.03 | 4.5 ± 0.41 |

| Methionine | |||

| Early | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 1.38 ± 0.08 | 1.22 ± 0.03 |

| Middle | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.04 |

| Late | 0.03 ± 0.001 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.03 |

| Cysteine | |||

| Early | 0.04 ± 0.015 | 6.61 ± 0.24 | 3.63 ± 0.01 |

| Middle | 0.32 ± 0.001 | 13.74 ± 0.55 | 5.42 ± 0.15 |

| Late | 0.22 ± 0.002 | 6.91 ± 0.10 | 1.89 ± 0.01 |

Desulfurization activities (units of DBT converted to 2-HBP and DBTO2/mg DCW) of wt and recombinant strains (Pkap1-dszBCA and Pkap1-dszABC) grown in the presence of different sulfur sources (DMSO, sulfate, methionine, and cysteine; 0.5 mM). Maximum biodesulfurization activities for each strain are indicated in boldface. DCW, dry cell weight. See also Fig. 5.

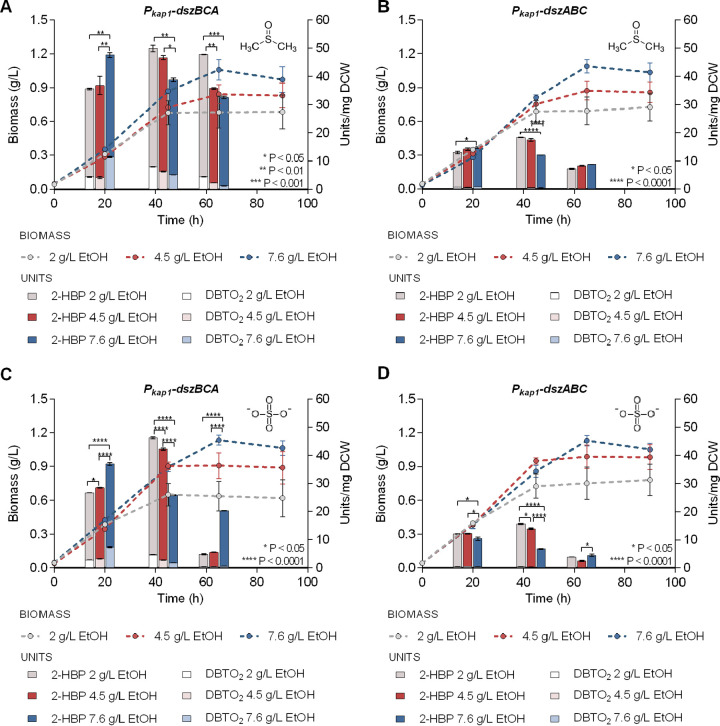

Effect of carbon source type and concentration on recombinant strain growth and catalytic activity.

The type of carbon source is also known to exert major effect on growth and catalytic capability (47, 49) of R. qingshengii IGTS8. In fact, bacterial cultures of wt IGTS8 strain supplemented with ethanol and DMSO as the sole carbon and sulfur sources, respectively, exhibit increased biodesulfurization compared to the combination of glucose or glycerol, and DMSO (47). To determine the preferred carbon source for the two recombinant strains when sulfate (0.5 mM) is provided as the sole sulfur source, we studied growth and biodesulfurization of resting cells with the supplementation of either ethanol, glycerol, or glucose as the sole carbon source (330 mM carbon) in the culture medium (Fig. 6). Biodesulfurization capability of Pkap1-dszBCA and Pkap1-dszABC strains was significantly enhanced with the supplementation of ethanol compared to glucose (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). However, the differences observed between ethanol and glycerol were significant only for the early log phase, while those between glycerol and glucose were not statistically significant. Moreover, the strain harboring the operon rearrangement exhibited increased desulfurization activity compared to Pkap1-dszABC strain for all carbon sources tested and all growth phases assessed (early, middle, and late log phases, P < 0.001). Growth phenotypes were also affected by the carbon source used for both recombinant strains. Glucose proved to be quite problematic since growth in glucose cultures, after short and fast growth for the first 20 h, practically leveled off at a final biomass concentration that was 70% lower than the corresponding ethanol and glycerol cultures (see also Table S3).

FIG 6.

Effects of different carbon sources on growth and biodesulfurization activity. The biomass (g/L) and desulfurization capabilities (units of DBT converted to 2-HBP and DBTO2/mg DCW) for genetically modified Pkap1-dszBCA (red) and Pkap1-dszABC (blue) strains, using either ethanol, glycerol, or glucose as the sole carbon source (330 mM carbon), are compared. Sulfate was used as the sole carbon source (0.5 mM). Measurement of desulfurization activity was performed after 20, 45, and 65 h of growth.

Since ethanol was shown to be the preferred carbon source for satisfactory growth and maximum biodesulfurization of recombinant strains, we further examined the impact of different ethanol concentrations (2, 4.5, and 7.6 g/L) in the presence of two sulfur sources (DMSO, Fig. 7A and B; sulfate, Fig. 7C and D). In general, desulfurization activity exhibited growth phase-dependent variations depending on the carbon source concentration. Importantly, for the Pkap1-dszBCA strain the biodesulfurization maximum appeared during the early log phase when grown on 7.6 g/L ethanol, but during mid-log phase for lower ethanol concentrations (P < 0.01; Fig. 7A and C). The measured activities for Pkap1-dszABC strain were overall lower, whereas supplementation of 2 g/L ethanol resulted in slightly elevated biodesulfurization mid-log phase (P < 0.05; Fig. 7B and D). Comparison of growth kinetic parameters revealed a statistically significant increase in μmax for both strains for the lower ethanol concentration (2 g/L versus 4.5 g/L, P < 0.01; 2 g/L versus 7.6 g/L, P < 0.0001), regardless of the sulfur source supplemented. Respective Cmax values became significantly higher for each strain as the supplemented carbon concentration increased (2 g/L versus 4.5 g/L versus 7.6 g/L, P < 0.01) (see Table S4).

FIG 7.

Optimization of ethanol concentration. The biomass (g/L) and desulfurization capabilities (units of DBT converted to 2-HBP and DBTO2/mg DCW) for the genetically modified Pkap1-dszBCA (A and C) and Pkap1-dszABC strains (B and D), using 2, 4.5, and 7.6 g/L ethanol as the sole carbon source, are compared. DMSO (A and B) or sulfate (C and D) were used as the sole sulfur source (0.5 mM). Measurement of desulfurization activity was performed after 20, 45, and 65 h of growth.

Quantification of dsz transcript levels.

To investigate the effect of promoter exchange and gene order rearrangement on dsz gene expression levels, a series of qPCRs were performed in the presence of a nonrepressive or a repressive sulfur source, i.e., DMSO or sulfate, respectively. Both sulfur sources were supplemented to the culture medium at 0.5 mM, which is the concentration used throughout our biodesulfurization studies (Fig. 8). All expression levels were normalized to the internal reference gene, gyrB, to allow the comparative evaluation of gene expression (for details, see Materials and Methods). Notably, biodesulfurization-repressive conditions were characterized by a statistically significant reduction of up to 47.43% in dsz gene expression for the wt strain compared to the supplementation of a nonrepressive sulfur source (dszABC DMSO versus dszABC sulfate; P < 0.05). Notably, the corresponding transcript levels of the recombinants exhibit strain- and gene-dependent variations when sulfate was supplemented instead of DMSO (see Fig. S2). For within-gene comparison between different strains grown on the same sulfur source, the expression levels of dszA, dszB, and dszC genes of the wt strain, were set as 1 arbitrary unit (AU). Next, the relative fold change was estimated for the recombinant strains Pkap1-dszBCA and Pkap1-dszABC (DMSO, Fig. 8A; sulfate, Fig. 8B). The Pkap1-dszBCA strain exhibited elevated dsz expression levels overall compared to the wt strain. The transcript levels of dszC, located in the second position of the rearranged operon Pkap1-dszBCA, were significantly enhanced compared to the respective levels of dszC in its native position, for both sulfur sources supplemented (2.8- to 4-fold, P < 0.05). However, the positive fold change observed for the other two genes (dszB and dszA) of strain Pkap1-dszBCA compared to their native positioning was relatively smaller and not statistically significant. The Pkap1-dszABC strain also exhibited marginal differences in dsz transcript levels compared to the wt strain. Notably, dszB and dszC mRNA levels were elevated for the Pkap1-dszBCA strain compared to the Pkap1-dszABC strain, hence accounting for the recorded superiority of the former. In addition, within-sample comparison of dszA versus dszB versus dszC gene expression levels was performed (Fig. 8C and D; see also Fig. S3), with the lowest gene expression of each sample set as 1 AU and the fold change of the other two genes estimated relative to the latter. Importantly, under nonrepressive conditions (DMSO) the wt strain (Pdsz-dszABC) showed slightly, but not significantly increased expression for dszB gene, which is positioned second in the native operon, compared to dszA. Increased transcript levels were also observed under desulfurization conditions for the second gene of the rearranged operon Pkap1-dszBCA, dszC, followed by dszB and dszA (sulfate and DMSO; P < 0.05 for dszA and dszB versus dszC). Comparison of the dsz transcript levels for strain Pkap1-dszABC revealed dszA to be the most abundant transcript regardless of the sulfur source supplemented (dszA versus dszB, P < 0.05; dszA versus dszC, P < 0.01), followed in order by dszB and dszC. Overall, the qPCR results offered valuable information on the effect of dsz gene positioning and expression levels on biodesulfurization activities and are discussed further below.

FIG 8.

Engineered loci exhibit differential dsz gene expression. (A and B) Within-gene comparison of dszA, dszB, and dszC transcriptional levels for the wt strain (Pdsz-dszABC) and genetically engineered strains (Pkap1-dszBCA and Pkap1-dszABC) in the presence of DMSO (A) or sulfate (B) as the sole sulfur sources. The fold change is expressed relative to the expression of the wt strain (the expression of the wt strain is set to 1 AU). A logarithmic scale was used. Values represent means ± the SEM. (C and D) Within-sample comparison of mRNA expression for wt and recombinant strains. Fold changes are presented relative to the lowest gene expression of each sample (set as 1 AU; values are displayed inside the circles). For an alternative graphical representation and statistical significance, see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material. Strains were grown in the presence of DMSO (C) or sulfate (D) as the sole sulfur source. All sulfur sources were supplemented at a concentration of 0.5 mM. Ethanol (165 mM) was used as the sole carbon source. All values were normalized to the housekeeping gene, gyrB. Number of biological/technical replicates = 2/2.

DISCUSSION

Several genetic engineering approaches have been employed for the enhancement of biodesulfurization in isolated biocatalysts or in related, nondesulfurizing species. Biodesulfurization is a complex, tightly regulated biological process; therefore, it is imperative to follow a suitable approach for the generation of recombinant biocatalysts. Integration of stable genetic changes via precise genome editing of a single locus allows the comparative study and targeted enhancement of the process by utilizing the native biocatalyst as a model system. We recently reported the targeted knockout of reverse transsulfuration genes in Rhodococcus qingshengii IGTS8 (47), allowing the elucidation of certain regulatory aspects of biodesulfurization.

Here, we employed a combination of genetic approaches for the development of two novel recombinant strains that effectively desulfurize under well-established repressive conditions. More specifically, we exchanged the native promoter of the dsz operon with the nonrepressible Pkap1 promoter derived from R. erythropolis KA2-5-1 for the construction of a recombinant IGTS8 biocatalyst. In addition, we combined this promoter replacement strategy with a rearrangement in the order of dsz genes and reconstruction of the dszB RBS for the generation of a second recombinant strain. Promoter replacement was employed previously as a strategy for overcoming the Pdsz repression problem in certain desulfurizing species, such as Arthrobacter sp. with utilization of the neomycin promoter (36) and in Rhodococcus spp. with the alternative promoters rrn (27), kap1 (30), P600 (37), and chloramphenicol resistance promoter (8). Rearrangement of the dsz operon was also examined as a means to enhance bacterial desulfurization activity of native or heterologous hosts (33, 35). However, all of the aforementioned approaches were based on expression of the dsz genes from small plasmids, raising the issue of biocatalyst stability (44). Here, all of the performed changes were integrated in the native dsz locus of the IGTS8 strain.

R. qingshengii recombinant strain growth remained largely unaffected by the genetic modifications for all sulfur sources supplemented except for DBT, indicating the neutrality of the dsz locus regarding basic sulfur assimilation regulation. Notably, comparison of the two recombinant strains in the presence of DBT as a sole sulfur source revealed that the combination of dsz operon rearrangement, gene overlap removal, and promoter replacement—and not promoter exchange alone—results in the transient accumulation of produced DBTO2. This observation underscores a delay in the DszA-dependent catalysis step, likely rendering DszA the new rate-limiting enzyme of the 4S pathway for the recombinant strain Pkap1-dszBCA. However, as growth of the strain progressed in DBT cultures the phenomenon was ameliorated, since DBTO2 is probably further converted to the end product 2-HBP. Notably, DBTO2 was also produced by strain Pkap1-dszABC grown on rich media, but not on any other sulfur source tested in the present study. This observation resembled the findings of Matsui et al. (27), wherein product formation profiles were associated with distinct sulfur sources. Importantly, the calculated maximum biomass concentration of recombinant Pkap1-dszBCA exhibited a statistically significant difference when grown in the presence of DBT, likely reflecting the increased capability for sulfur extraction from DBT and assimilation into biomass. The small differences observed between the calculated Cmax values and the attained biomass concentrations at 96 h can be attributed to the phase of the culture, which probably had not yet exited the deceleration growth phase at the time of the final growth measurement. The combination of promoter replacement, gene overlap removal, and operon rearrangement led to the highest biodesulfurization activities compared to the other two strains, while desulfurization of the Pkap1-dszABC recombinant compared to the wt strain was also enhanced for all culture media, except for CDM supplemented with DMSO as the sole sulfur source. This is possibly explained by the slightly reduced dszB and dszC transcript levels of the strain in the presence of DMSO, considering also that DszB is known to be responsible for the rate-limiting step of the process in the native operon (50).

The acquired advantage of promoter replacement on biodesulfurization capability became increasingly evident with the single supplementation of otherwise repressive sulfur sources, and especially sulfate, since an 86-fold increase was observed for the Pkap1-dszBCA recombinant compared to the wt strain. Notably, a lower carbon content resulted in the highest growth rates, whereas higher carbon concentrations led to higher biomass concentrations. Elucidation of these operational parameters is expected to help toward bioprocess scale-up for industrial applications, since maximum biocatalyst growth without losses in desulfurization activity is necessary for an efficient and economically viable biphasic BDS process with resting cells as biocatalysts (51).

Investigation of the dsz transcription profile of recombinant R. qingshengii IGTS8 strains suggests that the marginally to significantly enhanced dsz expression levels in the presence of sulfate (dszB and dszC for Pkap1-dzBCA; dszA for Pkap1-dszABC) might be responsible for the significant biodesulfurization enhancement observed for both recombinant strains. Importantly, any change concerning dszB gene expression might have an even more serious impact on the BDS phenotype, since DszB is known to be responsible for the rate-limiting step of the desulfurization process (32), and the gene overlap in the native dsz operon is known to disproportionally affect DszB protein levels (34). Therefore, the dszB RBS reconstruction in recombinant strain Pkap1-dszBCA is expected to have an extra positive effect on desulfurization activity that is nondetectable at a transcriptional level. Another puzzling observation is that the transcriptional levels of the wt strain were significantly reduced but not completely diminished in the presence of 0.5 mM sulfate, and these low mRNA levels did not correspond to a detectable biodesulfurization activity. Rhodococcus spp. cannot desulfurize in the presence of more than 0.25 mM sulfate (30) and exhibit dosage-dependent repression for cosupplementation of sulfate and DBT via a presumably indirect mechanism (25, 52). Sulfate supplementation led to repression of dszABC operon expression and nondetectable BDS activity of the wt strain, when a high concentration was used (1 mM), but the strain exhibited desulfurization activity when 0.1 mM sulfate was supplemented (47). In addition, it was reported that transcription from the dsz promoter is strongly repressed by a very high concentration of sulfate (50 mM) under cosupplementation with 1.5 mM DMSO (25). To our knowledge, there are currently no studies reporting the transcript levels of dsz enzymes under low concentrations of supplemental sulfate (<1 mM) as the sole sulfur source. The effect of sulfate addition is usually studied under DBT or DMSO cosupplementation and is correlated with a reduction in the production of 2-HBP and Dsz protein levels (8, 25, 27). Therefore, although the observed decrease in the presence of 0.5 mM sulfate is seemingly low, it is possible that a certain critical dsz mRNA threshold is required for expression initiation by the translation machinery, and/or regulation in the presence of sulfate as sole sulfur source occurs at the posttranscriptional level (53–55). Certain examples of similar repression mechanisms are reported for the expression of the cys genes, which is reduced to 40 to 50% of fully derepressed values during growth in the presence of excess inorganic sulfate (56, 57).

Within-sample analysis of transcript levels also unveiled certain variations of dsz gene expression. Transcript abundance was not always reduced according to the distance from the promoter as with plasmid-borne operons (33), but in contrast, when expressed from the same genomic locus, the promoter per se, gene positioning inside the operon, and sulfur source type, seemingly affected the mRNA ratios. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear; however, transcriptional abundance is often correlated with culture conditions and with genomic features, including local neighboring regions, positioning of cis-regulatory elements, and sequence intrinsic properties (50, 58–61). Notably, the kap1 promoter elicits a strong polarization effect on the native but not on the rearranged operon, likely due to dszB gene-specific properties (50). Furthermore, it is possible that not only dsz expression levels, but also the dsz transcript ratio, has a regulatory role in the Dsz protein expression and/or the biodesulfurization activity of strain IGTS8.

Overall, our results highlight the importance of performing genetically stable changes, not only for the enhancement of bacterial desulfurization but also for collecting valuable information on the complex mechanisms underlying the process. The advanced R. qingshengii IGTS8 biocatalysts generated here harbor stable genetic modifications and simultaneously exhibit an important enhancement of biodesulfurization activity, especially in the presence of selected sulfur sources that are repressive for the wild-type strain IGTS8. Thus, they present excellent candidates for further process optimization studies and could be exploited in the prospect of developing of a more viable commercial oil biodesulfurization process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Rhodococcus qingshengii IGTS8 was purchased from ATCC (53968). Escherichia coli DH5a and S17-1 strains were used for restriction-ligation cloning and conjugation purposes, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this studya

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. qingshengii | ||

| IGTS8 (wt) | DBT-degrading bacterium, wt strain | ATCC 53968 |

| dszΔ | Genetically engineered IGTS8 strain with Pdsz-dszA-dszB-dszC operon deletion | This study |

| Pkap1-dszABC | Genetically engineered IGTS8 strain harboring Pkap1-dszA-dszB-dszC operon in the dsz locus | This study |

| Pkap1-dszBCA | Genetically engineered IGTS8 strain harboring Pkap1-dszB-dszC-dszA rearranged operon in the dsz locus; derived from the dszΔ strain | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5a | F– Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 hsdR17 (rK– mK+) recA1 endA1 relA1 | Laboratory stock |

| S17-1 | recA pro hsdR RP4-2-Tc::Mu-Km::Tn7 | Laboratory stock |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK18mobsacB | Suicide vector derived from plasmid pK18; RP4 mob, sacB; Kanr | 63 |

| pIGTS8dszΔ | Derived from pK18mobsacB for dsz locus deletion; RP4 mob, sacB; Kanr | This study |

| pIGTS8-5′Pdsz-3′Pdsz | Derived from pK18mobsacB, harboring the flanking regions of Pdsz promoter; RP4 mob, sacB; Kanr | This study |

| pIGTS8-5′Pdsz-Pkap1-3′Pdsz | Derived from pIGTS8-5′Pdsz-3′Pdsz for replacing Pdsz with Pkap1; RP4 mob, sacB; Kanr | This study |

| pIGTS8-Pkap1-dszBCA | Derived from pIGTS8dszΔ for insertion of rearranged operon Pkap1-dszBCA in the dsz locus; RP4 mob, sacB; Kanr | This study |

wt, wild type; Kanr, kanamycin resistance.

R. qingshengii strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani peptone (LBP) broth (1% [wt/vol] Bacto peptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, and 1% [wt/vol] NaCl) at 30°C with shaking (180 rpm) or on LBP agar plates at 30°C. E. coli strains were grown in LB medium (1% [wt/vol] Bacto tryptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, and 1% [wt/vol] NaCl) at 37°C with shaking (180 to 200 rpm) or on LB agar plates at 37°C. Kanamycin (50 μg/mL) was used for plasmid selection in E. coli. Kanamycin (200 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL) were used to select R. qingshengii transconjugants in culture media. Counterselection was performed on no-salt LBP (NSLBP) plates with 10% (wt/vol) sucrose. Sulfur sources were supplemented at a final concentration of 0.5 mM S, unless stated otherwise. For biodesulfurization studies, R. qingshengii cells were grown on LB broth (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl), nutrient broth (3 g/L meat extract, 5 g/L gelatin peptone), or a sulfur-free synthetic medium (CDM), as previously described (47). CDM was supplemented with 0.5 mM MgSO4, DMSO, l-methionine, l-cysteine, or 0.1 mM DBT as the sole sulfur source and 165 mM ethanol, 55 mM glucose, or 110 mM glycerol as carbon sources (330 mM carbon), unless stated otherwise. pK18mobsacB (Life Science Market, Europe) was used as a cloning and mobilization vector.

Enzymes and chemicals.

All restriction enzymes were purchased from TaKaRa Bio (Lab Supplies Scientific SA, Hellas, Greece). Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Kappa Lab SA, Hellas, Greece) and AppliChem (Bioline Scientific SA, Hellas, Greece). Conventional and high-fidelity PCR amplifications were performed using KAPA Taq DNA and Kapa HiFi polymerases, respectively (Kapa Biosystems, Lab Supplies Scientific SA). All oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurofins Genomics (Vienna, Austria) and are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Technique and oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Strain construction | |

| dszUp-F | CGCGAAGCTTGAACGTGGTGACCGACTCGGC |

| dszUp-R | CGCGCTGCAGTCGGGTCAAGGTGACGGTGACGG |

| dszDown-F | CGCGCCCGGGGGATCTGAGGCGCTGATCGAGG |

| dszDown-R | CGCGGAATTCGTGACGGTGACCGCACCGCGG |

| PdszUp-F | GCGCAAGCTTGGTTTCAGTCCTGGGCGGTCACC |

| PdszDown-F | CGCGCGGATCCATGACTCAACAACGACAAATGCATCTGG |

| PdszDown-R | GCGCGAATTCTCATGAAGGTTGTCCTTGCAGTTGTG |

| Pkap1Nat-F | GCGCCTGCAGGACGTGGCTGTTGCTGACCGTC |

| Pkap1Nat-R | GCGCGGATCCTCCTCCTTTCGAATTGTCTTCTGGCGCGTC |

| Pkap1Re-F | GCGCGTCTAGAGACGTGGCTGTTGCTGACCGTC |

| Pkap1Re-R | GCGCAGATCTTCGAATTGTCTTCTGGCGCGTC |

| dszB-F | GCGCAGATCTAAGGAGGATATGAAATGACAAGCCGCGTCGACCC |

| dszB-R | GCGCTCTAGATCCTCCTTCTATCGGTGGCGATTGAGGCTG |

| dszC-F | GCGCTCTAGAATGACACTGTCACCTGAAAAGCAG |

| dszC-R | CGCGGCGGCCGCCCTCCTTTCAGGAGGTGAAGCCGGGAATC |

| dszA-F | CGCGGCGGCCGCATGACTCAACAACGACAAATGCATCTG |

| dszA-R | GCGCGACTAGTTCATGAAGGTTGTCCTTGCAGTTG |

| Sequencing | |

| M13F | AGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGACGTT |

| M13R | GAGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG |

| dsz-5F-check | GTCAGGCTCAACGTTGACTGCAC |

| dsz-3R-check | CGCCACCTCAACTTCTACGAGAC |

| 1200-dsz-F-check | CGGACCGAGCACCCGAGAGCAC |

| 500-dsz-F-check | CATTGGAAGCTCATGCGCGAGCATC |

| dszA-check | GACACTCCGATCAAGGACATCCTG |

| dszB-check | CCTCGCCCTCCTGGAGCGCACACAGC |

| dszC-check | GCGCACCCACTCCCTGCACGACCCGG |

| qPCR | |

| QdszAF | CTACTATCCCCCGTATCACGTTG |

| QdszAR | CGTCGTGTTCCAGATGCTGAT |

| QdszBF | GCGTATCGACCGGAGCAGT |

| QdszBR | GCAAGTTGTTGGTGAGCAGGA |

| QdszCF | GGTTCCACGGACTTCCACAA |

| QdszCR | GCGATCCCCAGATAGACGTTG |

| QgyrBF | GCTGCCCAGAAGTCAGATACA |

| QgyrBR | TCGACGACCTCCCAAATGAG |

Genetic manipulations, DNA sequence analysis, and gene synthesis.

The genomic DNA of IGTS8 was isolated using the NucleoSpin tissue DNA extraction kit (Macherey-Nagel, Lab Supplies Scientific SA, Hellas) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmid isolations were performed using the Nucleospin plasmid kit, while DNA gel extraction or PCR product purification were performed using the Nucleospin Extract II kit (Macherey-Nagel, Lab Supplies Scientific SA). DNA sequences were determined by Sanger sequencing by Eurofins-Genomics. The DNA sequence for promoter kap1 was synthesized by Eurofins-Genomics based on the published sequence (GenBank accession number AB083090.1).

Construction of genetically engineered strains.

An unmarked, precise gene deletion of the entire dsz locus (Pdsz-dszA-dszB-dszC) was created using a two-step allelic exchange protocol (62). Upstream and downstream flanking regions of the locus were amplified and cloned into the pK18mobsacB vector (63), using the primer pairs dszUp-F/dszUp-R and dszDown-F/dszDown-R, respectively, yielding plasmid pIGTS8dszΔ. For exchanging the Pdsz promoter with Pkap1, the flanking regions of Pdsz promoter sequence were cloned into the pK18mobsacB vector, using primer pairs PdszUp-F/PdszUp-R and PdszDown-F/PdszDown-R yielding plasmid pIGTS8-5′Pdsz-3′Pdsz. The Pkap1 fragment was cloned into pIGTS8-5′Pdsz-3′Pdsz using the primer pair Pkap1Nat-F/Pkap1Nat-R, to construct the plasmid pIGTS8-5′Pdsz-Pkap1-3′Pdsz. For operon rearrangement, Pkap1, dszB, dszC, and dszA were cloned into plasmid pIGTS8dszΔ using the primer pairs Pkap1Re-F/Pkap1Re-R, dszB-F/dszB-R, dszC-F/dszC-R, and dszA-F/dszA-R, respectively, yielding plasmid pIGTS8-Pkap1-dszBCA. Escherichia coli S17-1 competent cells were transformed with each of the modified plasmids. R. qingshengii IGTS8 genetically modified strains were created after conjugation (39) with E. coli S17-1 transformants, using a two-step homologous recombination (HR) process. For the generation of the dszΔ and Pkap1-dszABC strains, wild-type R. qingshengii IGTS8 was used as the recipient strain. For the construction of the Pkap1-dszBCA strain, the knockout dszΔ strain was used as the recipient strain. Mating was performed on LBP agar plates. Following the first crossover event, R. qingshengii transconjugants were grown on LBP plates supplemented with kanamycin (200 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (10 μg/mL). Selected transconjugants were streak purified in the presence of kanamycin and nalidixic acid on LBP plates or on NSLBP plates supplemented with 10% (wt/vol) sucrose. Sucrose-sensitive and kanamycin-resistant IGTS8 transconjugants were screened with PCR using the primers dsz-5F-check, dsz-3R-check, M13F, and M13R (Table 3) and grown in LB overnight to induce the second HR event. Recombinant strains were grown on selective media containing 10% (wt/vol) sucrose and tested for kanamycin sensitivity to remove incomplete crossover events. All manipulations in the dsz locus were verified with PCR and confirmed by DNA sequencing using the external primer pair dsz-5F-check/dsz-3R-check and the internal sequencing primers listed in Table 3. The sequences of the dsz loci from genetically engineered Rhodococcus dszΔ, Pkap1-dszBCA, and Pkap1-dszABC strains are provided in the supplemental material.

Growth and desulfurization studies.

For growth studies and resting cell biodesulfurization assays, wt and recombinant R. qingshengii strains were grown in rich media (LB and NB) or in CDM under different carbon and sulfur source types and concentrations. The inoculum was prepared by cell harvesting and two washes in S-free Ringer’s solution (pH 7.0) as described by Martzoukou et al. (47). For each condition, an initial biomass concentration of 0.045 to 0.055 g/L was applied. Biomass concentration, expressed as the dry cell weight (DCW), was estimated by measurement of optical density at 600 nm with a Multiskan GO microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and calculations were based on an established calibration curve. For the DBT cultures shown in Fig. 3, strains were grown in glass culture tubes with a working volume of 5 mL at 30°C and 180 rpm, while five identical cultures were used for each strain. Samples (0.15 mL) were collected from the actively growing cultures in Eppendorf tubes, and an equal volume of acetonitrile was added. Suspensions were vortexed and centrifuged (14,000 × g; 10 min). Supernatant was collected for HPLC analysis. For the results shown in Fig. 4 to 8, growth took place in 96-well cell culture plates (F-bottom; Greiner Bio-One, Fisher Scientific, USA) with a 150-μL working volume in thermostated plate-shakers at 30°C and 600 rpm (PST-60HL, BioSan; Pegasus Analytical SA), while 17 to 27 identical well cultures were used. A simple unstructured logistic kinetic model was employed for microbial growth modeling as previously described (47).

The resting cell biodesulfurization assays were performed essentially as described previously (47). In brief, cells from two to four identical well cultures were collected by centrifugation, washed with a S-free Ringer solution (pH 7.0), and resuspended in 0.45 mL of 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 8.0). Suspensions were split into three 0.15-mL aliquots with an equal volume of a 2 mM DBT solution in the same buffer being subsequently added in each. A desulfurization reaction was performed under shaking (1,200 rpm) for 30 min at 30°C in a thermostated shaker (Thermo Shaker TS-100; BOECO, Germany) and terminated with the addition of 0.3 mL of acetonitrile under vigorous vortexing. Suspensions were centrifuged (14,000 × g; 10 min), and the supernatant was collected for biodesulfurization product analysis through HPLC. One of the tubes, where 0.3 mL of acetonitrile was added immediately after DBT addition (t = 0), was used as blank. The desulfurization capability was expressed as units per mg DCW, with one unit corresponding to the release of 1 nmol of 2-HBP per hour. Assay linearity was verified previously (47) for different biomass concentrations, up to 2 h reaction time and up to 100 μM of produced 2-HBP.

HPLC analysis.

HPLC was used to quantify 2-HBP and DBTO2. The analysis was performed on an Agilent HPLC 1220 Infinity LC System equipped with a fluorescence detector (FLD). A C18 reversed-phase column (Poroshell 120 EC-C18, 4 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm; Agilent) was used for the separation. The elution profile (at 1.2 mL/min) consisted of a 4-min isocratic elution with 60/40 (vol/vol) acetonitrile/H2O, followed by a 15-min linear gradient to 100% acetonitrile. Fluorescence detection was performed at an excitation wavelength of 245 nm and an emission wavelength of 345 nm. Quantification was performed using appropriate calibration curves with the corresponding standards (linear range, 10 to 1,000 ng/mL).

Extraction of total RNA.

R. qingshengii IGTS8 wt, Pkap1-dszBCA, and Pkap1-dszABC strains were grown in CDM containing DMSO or MgSO4 as the sole sulfur source (0.5 mM S). Ethanol was used as a carbon source to a final concentration of 165 mM (330 mM carbon). Cells were harvested at mid-log phase and incubated with lysozyme (20 mg/mL) for 2 h at 25°C. Total RNA isolation was performed using a NucleoSpin RNA kit (Macherey-Nagel, Lab Supplies Scientific SA) according to manufacturer guidelines. RNA samples were treated with DNase I as part of the kit procedure to eliminate any genomic DNA contamination. RNA concentration and purity were determined at 260 and 280 nm using a μDrop Plate with a Multiskan GO microplate spectrophotometer, while RNA integrity was evaluated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

First-strand cDNA synthesis.

Reverse transcription took place in a 20-μL reaction mixture containing 500 ng of total RNA template, 0.5 mM dNTP Mix, 200 U of SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Antisel SA, Hellas, Greece), 40 U of RNaseOUT recombinant RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen, Antisel SA), and 4 μM random hexamer primers (TaKaRa Bio, Lab Supplies Scientific SA). Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C for 50 min, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70°C for 15 min.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

qPCR assays were performed on a 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) using SYBR green I dye for the quantification of dszA, dszB, and dszC transcript levels. Specific primers were designed based on the published sequences of IGTS8 desulfurization operon (GenBank accession no. U08850.1 for dszABC) and IGTS8 chromosome (GenBank accession no. CP029297.1 for gyrB) and are listed in Table 3. The gene-specific amplicons generated were 143 bp for dszA, 129 bp for dszB, 152 bp for dszC, and 158 bp for gyrB. The qPCR mixtures and thermal protocol were set up as described previously (47). All qPCRs were performed using two biological and two technical replications for each tested sample and target. The average threshold cycle (CT) of each duplicate was used in quantification analyses according to the 2–ΔΔCT relative quantification (RQ) method for comparison of the expression of each gene in different samples. For within-sample gene expression comparisons, the 2–ΔCT formula was applied. A cDNA sample derived from R. qingshengii IGTS8 grown on 1 mM DMSO for 66 h was used as the assay calibrator. The DNA gyrase subunit B (gyrB) gene from strain IGTS8 was used as an internal reference gene for normalization purposes. All qPCRs were performed according to the minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments (MIQE) guidelines (47). According to the procedure described above in “Growth and desulfurization studies,” every biological replicate (n = 2) further corresponds to the biological mean of two to five replicate wells.

Statistical analysis.

All reported values represent means ± standard error of mean (SEM). One-sample t test was performed to test significance within samples. For comparison of two data sets, a two-sided paired t test was performed. For comparison of three or more data sets, results were statistically analyzed by performing one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. The confidence level was set to 95% in all analyses. GraphPad Prism 6.1 software was used for statistical analyses.

Data availability.

Data are available upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research project was supported by Action RESEARCH–CREATE–INNOVATE cofinanced by the European Union and national resources through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation (EPAnEK)/NSRF (2014 to 2020; project T1EDK-02074, MIS 5030227).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Dimitris G. Hatzinikolaou, Email: dhatzini@biol.uoa.gr.

Arpita Bose, Washington University in St. Louis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kilbane JJ. 2017. Biodesulfurization: how to make it work? Arab J Sci Eng 42:1–9. 10.1007/s13369-016-2269-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson D, Cognat V, Goodfellow M, Koechler S, Heintz D, Carapito C, Van Dorsselaer A, Mahmoud H, Sangal V, Ismail W. 2020. Phylogenomic classification and biosynthetic potential of the fossil fuel-biodesulfurizing Rhodococcus strain IGTS8. Front Microbiol 11:1417. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denome SA, Olson ES, Young KD. 1993. Identification and cloning of genes involved in specific desulfurization of dibenzothiophene by Rhodococcus sp. strain IGTS8. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:2837–2843. 10.1128/aem.59.9.2837-2843.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denis-Larose C, Labbé D, Bergeron H, Jones AM, Greer CW, Al-Hawari J, Grossman MJ, Sankey BM, Lau PCK. 1997. Conservation of plasmid-encoded dibenzothiophene desulfurization genes in several rhodococci. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:2915–2919. 10.1128/aem.63.7.2915-2919.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shavandi M, Sadeghizadeh M, Khajeh K, Mohebali G, Zomorodipour A. 2010. Genomic structure and promoter analysis of the dsz operon for dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization from Gordonia alkanivorans RIPI90A. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87:1455–1461. 10.1007/s00253-010-2605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Ma T, Lian K, Zhang Y, Tian H, Ji K, Li G. 2013. Genetic analysis of benzothiophene biodesulfurization pathway of Gordonia terrae strain C-6. PLoS One 8:e84386. 10.1371/journal.pone.0084386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher JR, Olson ES, Stanley DC. 1993. Microbial desulfurization of dibenzothiophene: a sulfur-specific pathway. FEMS Microbiol Lett 107:31–35. 10.1016/0378-1097(93)90349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piddington CS, Kovacevich BR, Rambosek J. 1995. Sequence and molecular characterization of a DNA region encoding the dibenzothiophene desulfurization operon of Rhodococcus sp. strain IGTS8. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:468–475. 10.1128/aem.61.2.468-475.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bordoloi NK, Rai SK, Chaudhuri MK, Mukherjee AK. 2014. Deep-desulfurization of dibenzothiophene and its derivatives present in diesel oil by a newly isolated bacterium Achromobacter sp. to reduce the environmental pollution from fossil fuel combustion. Fuel Process Technol 119:236–244. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2013.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai Y, Shao R, Qi G, Ding B-B. 2014. Enhanced dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization by immobilized cells of Brevibacterium lutescens in n-octane–water biphasic system. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 174:2236–2244. 10.1007/s12010-014-1184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bordoloi NK, Bhagowati P, Chaudhuri MK, Mukherjee AK. 2016. Proteomics and metabolomics analyses to elucidate the desulfurization pathway of Chelatococcus sp. PLoS One 11:e0153547. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohebali G, Ball AS, Rasekh B, Kaytash A. 2007. Biodesulfurization potential of a newly isolated bacterium, Gordonia alkanivorans RIPI90A. Enzyme Microb Technol 40:578–584. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akhtar N, Akhtar K, Ghauri MA. 2018. Biodesulfurization of thiophenic compounds by a 2-hydroxybiphenyl-resistant Gordonia sp. HS126-4N carrying dszABC genes. Curr Microbiol 75:597–603. 10.1007/s00284-017-1422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada H, Nomura N, Nakahara T, Maruhashi K. 2002. Analysis of dibenzothiophene metabolic pathway in Mycobacterium strain G3. J Biosci Bioeng 93:491–497. 10.1016/S1389-1723(02)80097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Zhang Y, Wang MD, Shi Y. 2005. Biodesulfurization of dibenzothiophene and other organic sulfur compounds by a newly isolated Microbacterium strain ZD-M2. FEMS Microbiol Lett 247:45–50. 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang JH, Rhee S-K, Chang YK, Chang HN. 1998. Desulfurization of diesel oils by a newly isolated dibenzothiophene-degrading Nocardia sp. strain CYKS2. Biotechnol Prog 14:851–855. 10.1021/bp9800788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Davaadelger B, Salazar JK, Butler RR, Pombert J-F, Kilbane JJ, Stark BC. 2015. Isolation and characterization of an interactive culture of two Paenibacillus species with moderately thermophilic desulfurization ability. Biotechnol Lett 37:2201–2211. 10.1007/s10529-015-1918-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nassar HN, Abu Amr SS, El-Gendy NS. 2021. Biodesulfurization of refractory sulfur compounds in petro-diesel by a novel hydrocarbon tolerable strain Paenibacillus glucanolyticus HN4. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 28:8102–8116. 10.1007/s11356-020-11090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunam IBW, Yaku Y, Hirano M, Yamamura K, Tomita F, Sone T, Asano K. 2006. Biodesulfurization of alkylated forms of dibenzothiophene and benzothiophene by Sphingomonas subarctica T7b. J Biosci Bioeng 101:322–327. 10.1263/jbb.101.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohshiro T, Hirata T, Izumi Y. 1996. Desulfurization of dibenzothiophene derivatives by whole cells of Rhodococcus erythropolis H-2. FEMS Microbiol Lett 142:65–70. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08409.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kobayashi M, Onaka T, Ishii Y, Konishi J, Takaki M, Okada H, Ohta Y, Koizumi K, Suzuki M. 2000. Desulfurization of alkylated forms of both dibenzothiophene and benzothiophene by a single bacterial strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett 187:123–126. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu B, Ma C, Zhou W, Wang Y, Cai X, Tao F, Zhang Q, Tong M, Qu J, Xu P. 2006. Microbial desulfurization of gasoline by free whole cells of Rhodococcus erythropolis XP. FEMS Microbiol Lett 258:284–289. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohamed ME-S, Al-Yacoub ZH, Vedakumar JV. 2015. Biocatalytic desulfurization of thiophenic compounds and crude oil by newly isolated bacteria. Front Microbiol 6:112. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kilbane JJ, Jackowski K. 1992. Biodesulfurization of water-soluble coal-derived material by Rhodococcus rhodochrous IGTS8. Biotechnol Bioeng 40:1107–1114. 10.1002/bit.260400915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li MZ, Squires CH, Monticello DJ, Childs JD. 1996. Genetic analysis of the dsz promoter and associated regulatory regions of Rhodococcus erythropolis IGTS8. J Bacteriol 178:6409–6418. 10.1128/jb.178.22.6409-6418.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohshiro T, Suzuki K, Izumi Y. 1996. Regulation of dibenzothiophene degrading enzyme activity of Rhodococcus erythropolis D-1. J Ferment Bioeng 81:121–124. 10.1016/0922-338X(96)87588-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsui T, Noda K, Tanaka Y, Maruhashi K, Kurane R. 2002. Recombinant Rhodococcus sp. strain T09 can desulfurize DBT in the presence of inorganic sulfate. Curr Microbiol 45:240–244. 10.1007/s00284-002-3739-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim YJ, Chang JH, Cho K-S, Ryu HW, Chang YK. 2004. A physiological study on growth and dibenzothiophene (DBT) desulfurization characteristics of Gordonia sp. Korean J Chem Eng 21:436–441. 10.1007/BF02705433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alves L, Salgueiro R, Rodrigues C, Mesquita E, Matos J, Gírio FM. 2005. Desulfurization of dibenzothiophene, benzothiophene, and other thiophene analogs by a newly isolated bacterium, Gordonia alkanivorans strain 1B. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 120:199–208. 10.1385/abab:120:3:199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noda K, Watanabe K, Maruhashi K. 2003. Cloning of a rhodococcal promoter using a transposon for dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization. Biotechnol Lett 25:1875–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee S-K, Chang JH, Chang YK, Chang HN. 1998. Desulfurization of dibenzothiophene and diesel oils by a newly isolated Gordona strain, CYKS1. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:2327–2331. 10.1128/AEM.64.6.2327-2331.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray KA, Pogrebinsky OS, Mrachko GT, Xi L, Monticello DJ, Squires CH. 1996. Molecular mechanisms of biocatalytic desulfurization of fossil fuels. Nat Biotechnol 14:1705–1709. 10.1038/nbt1296-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li G, Li S, Zhang M, Wang J, Zhu L, Liang F, Liu R, Ma T. 2008. Genetic rearrangement strategy for optimizing the dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization pathway in Rhodococcus erythropolis. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:971–976. 10.1128/AEM.02319-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li G, Ma T, Li S, Li H, Liang F, Liu R. 2007. Improvement of dibenzothiophene desulfurization activity by removing the gene overlap in the dsz operon. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 71:849–854. 10.1271/bbb.60189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martínez I, Mohamed MES, Rozas D, García JL, Díaz E. 2016. Engineering synthetic bacterial consortia for enhanced desulfurization and revalorization of oil sulfur compounds. Metab Eng 35:46–54. 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serbolisca L, de Ferra F, Margarit I. 1999. Manipulation of the DNA coding for the desulphurizing activity in a new isolate of Arthrobacter sp. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 52:122–126. 10.1007/s002530051498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franchi E, Rodriguez F, Serbolisca L, De Ferra F. 2003. Vector development, isolation of new promoters and enhancement of the catalytic activity of the Dsz enzyme complex in Rhodococcus sp. Oil Gas Sci Technol Rev IFP 58:515–520. 10.2516/ogst:2003035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sallam KI, Tamura N, Imoto N, Tamura T. 2010. New vector system for random, single-step integration of multiple copies of DNA into the Rhodococcus genome. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:2531–2539. 10.1128/AEM.02131-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Geize R, Hessels GI, van Gerwen R, van der Meijden P, Dijkhuizen L. 2001. Unmarked gene deletion mutagenesis of kstD, encoding 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase, in Rhodococcus erythropolis SQ1 using sacB as counter-selectable marker. FEMS Microbiol Lett 205:197–202. 10.1016/S0378-1097(01)00464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim HM, Chae TU, Choi SY, Kim WJ, Lee SY. 2019. Engineering of an oleaginous bacterium for the production of fatty acids and fuels. Nat Chem Biol 15:721–729. 10.1038/s41589-019-0295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Round JW, Roccor R, Eltis LD. 2019. A biocatalyst for sustainable wax ester production: re-wiring lipid accumulation in Rhodococcus to yield high-value oleochemicals. Green Chem 21:6468–6482. 10.1039/C9GC03228B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakashima N, Tamura T. 2004. A novel system for expressing recombinant proteins over a wide temperature range from 4 to 35°C. Biotechnol Bioeng 86:136–148. 10.1002/bit.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirasawa K, Ishii Y, Kobayashi M, Koizumi K, Maruhashi K. 2001. Improvement of desulfurization activity in Rhodococcus erythropolis KA2-5-1 by genetic engineering. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65:239–246. 10.1271/bbb.65.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang Y, Yu H. 2021. Genetic toolkits for engineering Rhodococcus species with versatile applications. Biotechnol Adv 49:107748. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boltes K, Alonso del Aguila R, García-Calvo E. 2013. Effect of mass transfer on biodesulfurization kinetics of alkylated forms of dibenzothiophene by Pseudomonas putida CECT5279. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 88:422–431. 10.1002/jctb.3877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent AT, Nyongesa S, Morneau I, Reed MB, Tocheva EI, Veyrier FJ. 2018. The mycobacterial cell envelope: a relict from the past or the result of recent evolution? Front Microbiol 9:2341. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martzoukou O, Glekas PD, Avgeris M, Mamma D, Scorilas A, Kekos D, Amillis S, Hatzinikolaou DG. 2022. Interplay between sulfur assimilation and biodesulfurization activity in Rhodococcus qingshengii IGTS8: insights into a regulatory role of the reverse transsulfuration pathway mBio 13:e00754-22. 10.1128/mbio.00754-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang P, Krawiec S. 1996. Kinetic analyses of desulfurization of dibenzothiophene by Rhodococcus erythropolis in batch and fed-batch cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:1670–1675. 10.1128/aem.62.5.1670-1675.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan H, Kishimoto M, Omasa T, Katakura Y, Suga KI, Okumura K, Yoshikawa O. 2000. Increase in desulfurization activity of Rhodococcus erythropolis KA2-5-1 using ethanol feeding. J Biosci Bioeng 89:361–366. 10.1016/S1389-1723(00)88959-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reichmuth DS, Blanch HW, Keasling JD. 2004. Dibenzothiophene biodesulfurization pathway improvement using diagnostic GFP fusions. Biotechnol Bioeng 88:94–99. 10.1002/bit.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohebali G, Ball AS. 2016. Biodesulfurization of diesel fuels: past, present and future perspectives. Int Biodeter Biodegrad 110:163–180. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2016.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka Y, Yoshikawa O, Maruhashi K, Kurane R. 2002. The cbs mutant strain of Rhodococcus erythropolis KA2-5-1 expresses high levels of Dsz enzymes in the presence of sulfate. Arch Microbiol 178:351–357. 10.1007/s00203-002-0466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richards J, Sundermeier T, Svetlanov A, Karzai A. 2008. Quality control of bacterial mRNA decoding and decay. Biochim Biophys Acta 1779:574–582. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson GE, Lalanne J-B, Peters ML, Li G-W. 2020. Functionally uncoupled transcription–translation in Bacillus subtilis. Nature 585:124–128. 10.1038/s41586-020-2638-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vargas-Blanco DA, Shell SS. 2020. Regulation of mRNA stability during bacterial stress responses. Front Microbiol 11:2111. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.02111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kertesz MA. 2000. Riding the sulfur cycle: metabolism of sulfonates and sulfate esters in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24:135–175. 10.1016/S0168-6445(99)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tao H, Bausch C, Richmond C, Blattner FR, Conway T. 1999. Functional genomics: expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J Bacteriol 181:6425–6440. 10.1128/JB.181.20.6425-6440.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brooks AN, Hughes AL, Clauder-Münster S, Mitchell LA, Boeke JD, Steinmetz LM. 2022. Transcriptional neighborhoods regulate transcript isoform lengths and expression levels. Science 375:1000–1005. 10.1126/science.abg0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scholz SA, Lindeboom CD, Freddolino PL. 2022. Genetic context effects can override canonical cis regulatory elements in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res 50:10360–10375. 10.1093/nar/gkac787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goormans AR, Snoeck N, Decadt H, Vermeulen K, Peters G, Coussement P, Van Herpe D, Beauprez JJ, De Maeseneire SL, Soetaert WK. 2020. Comprehensive study on Escherichia coli genomic expression: does position really matter? Metab Eng 62:10–19. 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brandis G, Cao S, Hughes D, Agashe D. 2019. Operon concatenation is an ancient feature that restricts the potential to rearrange bacterial chromosomes. Mol Biol Evol 36:1990–2000. 10.1093/molbev/msz129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang H, Yu T, Wang Y, Li J, Wang G, Ma Y, Liu Y. 2018. 4-Chlorophenol oxidation depends on the activation of an AraC-type transcriptional regulator, CphR, in Rhodococcus sp. strain YH-5B Front Microbiol 9:2418. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger W, Kalinowski J, Thierbach G, Pühler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73. 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download aem.01970-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.6 MB (622.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.