Abstract

Background

Delirium is a common, under-recognized, and often fatal condition in critically ill patients, characterized by acute disorder of attention and cognition. The global prevalence varies with a negative impact on outcomes. A paucity of Indian studies exists that have systematically assessed delirium.

Objective

A prospective observational study designed to determine the incidence, subtypes, risk factors, complications, and outcome of delirium in Indian intensive care units (ICUs).

Patients and methods

Among 1198 adult patients screened during the study period (December 2019–September 2021), 936 patients were included. The confusion assessment method score (CAM-ICU) and Richmond agitation sedation scale (RASS) were used, with additional confirmation of delirium by the psychiatrist/neurophysician. Risk factors and related complications were compared with a control group.

Results

Delirium occurred in 22.11% of critically ill patients. The hypoactive subtype was the most common (44.9%). The risk factors recognized were higher age, increased acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE-II) score, hyperuricemia, raised creatinine, hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, alcoholism, and smoking. Precipitating factors included patients admitted on noncubicle beds, proximity to the nursing station, requiring ventilation, as well as the use of sedatives, steroids, anticonvulsants, and vasopressors. Complications observed in the delirium group were unintentional removal of catheters (35.7%), aspiration (19.8%), need for reintubation (10.6%), decubitus ulcer formation (18.4%), and high mortality (21.3% vs 5%).

Conclusion

Delirium is common in Indian ICUs with a potential effect on length of stay and mortality. Identification of incidence, subtype, and risk factors is the first step toward prevention of this important cognitive dysfunction in the ICU.

How to cite this article

Tiwari AM, Zirpe KG, Khan AZ, Gurav SK, Deshmukh AM, Suryawanshi PB, et al. Incidence, Subtypes, Risk factors, and Outcome of Delirium: A Prospective Observational Study from Indian Intensive Care Unit. Indian J Crit Care Med 2023;27(2):111–118.

Keywords: Acute confusional state, Complications, Delirium, Intensive care unit, Mortality, Motor subtypes of delirium, Risk factors

Highlights

Delirium is a common, under-recognized, and often fatal condition in critically ill patients. A paucity of Indian studies exists that have systematically assessed delirium. The present Indian study is single-center prospective clinical observational noninterventional study with a large sample study population of 936 critically ill patients from Indian ICU.

Introduction

Delirium is a medical diagnosis defined by the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders fifth edition (DSM-5), as acute disturbance in attention and awareness with fluctuating course, with either disorganized thinking or an altered level of consciousness.1

Prevalence of delirium varies across the globe depending on factors such as the cohort of the patient studied, admission in intensive care, medical or surgical settings, need for ventilation, and screening tool used to diagnose it.2 A recent systematic review of 42 studies reported the incidence of delirium as high as 31.8% critically ill patients.3

Delirium is common in the ICU because it frequently occurs in the context of multiorgan failure and critical illness. Clinical manifestation of delirium varies from hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed subtypes, with hypoactive delirium being reported as most frequent among critically ill patients.4

It is often underrecognized, although having a significant and potential negative impact, resulting in extended lengths of stay and poor outcomes for ICU patients. The overall effect of delirium, apart from increased mortality and morbidity, translates into higher cost both within the ICU and hospital, as evident from the recent systematic review and meta-analysis.5

It is quite relevant to the Indian setting as far as the cost burden to the patient and caregiver is concerned.

In order to optimize healthcare spending and cut costs, delirium prevention or early detection of its precipitating and predisposing risk factors in the ICU may be a priority.

There are a few clinical studies that have reported delirium in Indian ICUs. We conducted a prospective observational study to estimate the incidence, subtypes, risk factors, associated complications, and outcome of delirium in Indian ICU settings.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

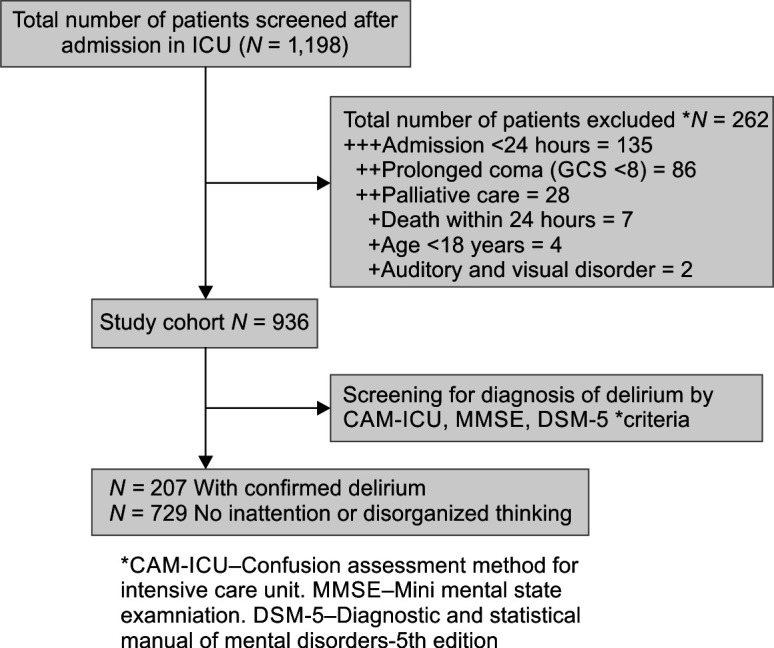

This single-center prospective observational study was performed after obtaining Institutional Ethical committee (IEC) approval in the critical care unit of tertiary care hospital in India. The study center is a level 3 semiclosed 48-bed ICU with a median APACHE-II score of 11 (8–14) and monthly standard mortality rate (SMR) of 0.75 in the preceding year. The study included all adult patients (age >18 years) who were admitted to the critical care unit for more than 24 hours during the study period (December 2019–September 2021). Patients with the Glasgow coma scale (GCS) <8, those with a mental disability or with a history of treatment for the same, patients with auditory or visual disorders, and patients who were under palliative care were excluded from the study sample (Flowchart 1).

Flowchart 1.

Flowchart of the patient

Data Collection

The study group patient's data were collected prospectively for age, gender, comorbid condition, history of alcohol and tobacco (habitual consumption), APACHE-II, GCS, subset category of admission (medical/surgical), infrastructural variable after admission to the ICU, including bed type (cubicle/noncubicle), presence or absence of window, proximity to nursing station/entrance or exit of critical care unit, and laboratory parameters, including serum electrolytes, renal function tests (urea/creatinine), and liver function tests (serum albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and serum albumin). There were additional data regarding use of mechanical ventilation (invasive vs noninvasive), need of drug opioids, sedatives, steroids, anticonvulsants, and vasopressors. Similarly, complications and outcome parameters, including events of removal of catheter, aspirations, reintubation, decubitus ulcers, length of stay in the ICU, length of stay in the hospital, and in-hospital mortality, were recorded prospectively both for the study populations and control group (100 nondelirium patients were included) for comparison.

Delirium Assessment

Diagnosis of delirium and subtype identification was made in study participants after fulfilling inclusion criteria, by following three steps:

First, they underwent evaluation on RASS. Richmond agitation sedation score components were assessed as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Richmond agitation sedation score (RASS)

| Score | Clinical condition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| +4 | Combative | Violent, immediate threat to staff |

| +3 | Very agitated | Pull at devices or remove tubes |

| +2 | Agitated | Nonpurposeful movements fight ventilator |

| +1 | Restless | Anxious, apprehensive |

| 0 | Alert and calm | |

| –1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert, sustained awakening to voice (eye-opening and contact >10 seconds) |

| –2 | Light sedation | Briefly awakens to voice (eye-opening and contact <10 seconds) |

| –3 | Moderate sedation | Movement or eye-opening to voice, no eye contact |

| –4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice, but eye-opening to physical stimuli |

| –5 | Unarousable | No response to voice or physical stimuli |

RASS >-2 proceed to ICU-CAM, RASS <-2 stop reassess later

It is the standard 10-point sedation scale with four levels of anxiety or agitation (+1 to +4), one level to denote a calm and alert state (0), and 5 levels to assess the level of sedation (−1 to −5). A score of −4 indicates that the patient is unresponsive to verbal stimulation and finally culminating in unarousable states (–5). It has good interrater reliability and validity.

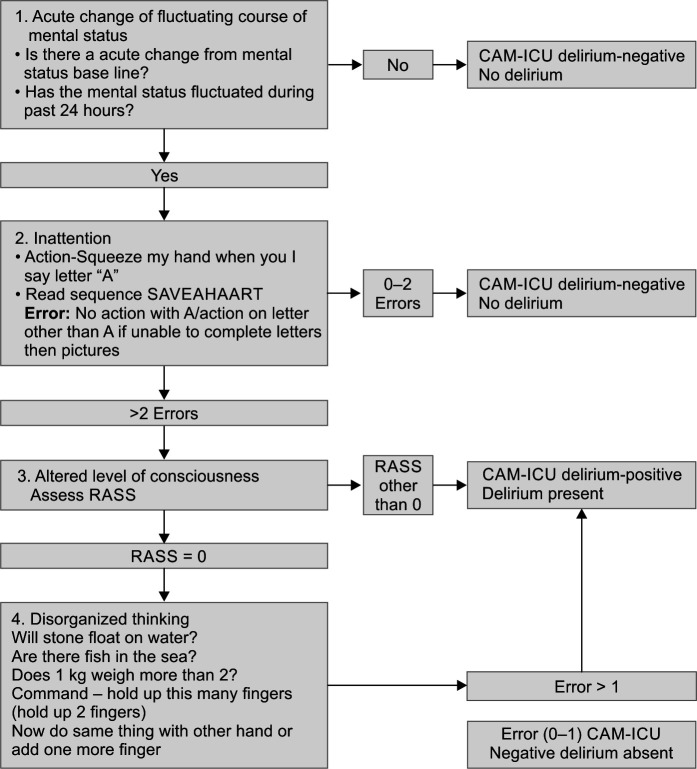

In the second step, those patients who were −3 to +4 on the RASS scale were evaluated further with CAM-ICU score shown in Flowchart 2.

Flowchart 2.

CAM-ICU screening used

It is the most reliable tool to diagnose delirium in all subsets of ICU patients, including those on mechanical ventilation.

In the final third step, motor subtyping of patients was done who were positive on CAM-ICU screening by the rating of RASS into three types:

Hyperactive delirium: persistently positive rating of RASS (+1 to +4) during most of the period while in delirium.

Hypoactive delirium: negative rating of RASS (0 to −4) during most of the period while in delirium.

Mixed type: considered when both positive and negative RASS values during the period of delirium.

A postgraduate critical care trainee doctors administered the CAM-ICU for the study. Patients positive in CAM-ICU were screened further either by a neurologist with the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) or a psychiatrist using the DSM-5 criteria. The diagnosis of delirium was confirmed by mutual consensus between the ICU team and psychiatrist/neurophysician. The duration of delirium was noted from the first positive CAM-ICU till three consecutive days of negative CAM-ICU assessment.

Informed Consent

The IEC approved the study protocol, and an observational study waived the need for patient-informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

Prospectively collected data were entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet and were tabulated. The incidence of delirium was calculated after the completion of data entry of the study population. Categorical variables were expressed by frequency and percentage. Quantitative data variables were expressed by using mean and standard deviation (SD). Data were further analyzed using student's t-test (continuous data) and Chi-square test (categorical data), using SPSS and Microsoft Excel. P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The present prospective observational single-center study was conducted at the critical care unit of a tertiary care hospital during the period from December 2019 to September 2021.

A total of 1198 patients admitted during the study period were screened, 262 patients were excluded. A total of 936 adult patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were analyzed as shown in Flowchart 1. On CAM-ICU screening, 216 patients tested positive for delirium, however, after additional review by a psychiatrist, 9 (4.34%) of 216 patients were removed due to differences in opinion, and a total of 207 (22.11%) patients were unanimously identified as delirium-positive.

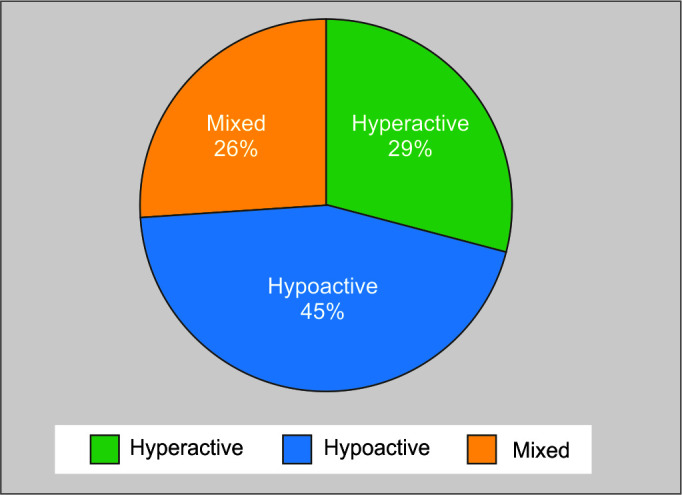

Number and incidence of hypoactive subtype 93 (44.9%) was predominant compared with hyperactive 60 (29%) and mixed 54 (26.1%), respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Subtypes of delirium

The mean duration of hyperactive delirium was 2.82 ± 1.00 days, of hypoactive delirium was 3.75 ± 0.84 days, and mixed delirium was 2.56 ± 0.82 days, respectively.

As depicted in Table 2 in the comparison of demographic profile and predisposing factors in delirium and nondelirium control group, advanced age (mean >58 years), hypothyroidism, addiction to alcohol, and smoking were found significantly associated (p < 0.05*) with delirium. Thirty people in this study group (14.5% of those who got delirium overall) had a history of alcoholism. Among the metabolic parameters, higher blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, total bilirubin, and lower albumin-level differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05*) in delirium group.

Table 2.

Demographics, predisposing, and precipitating factors in study and control group

| Variables | Delirium group n = 207 (22%) | Nondelirium group n = 100 (78%) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean | 58.19 | 47.85 | 0.001* |

| Sex (male/female) | 162/45 | 72/28 | NS |

| Medical case | 135 | 52 | |

| Surgical case | 72 | 48 | |

| Predisposing factors | |||

| Hypertension | 103 | 39 | NS |

| Diabetes | 94 | 35 | NS |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 | 12 | 0.037* |

| Ischemic heart disease (IHD) | 23 | 8 | NS |

| Chronic kidney disease (CKD) | 7 | 6 | NS |

| Chronic liver disease | 12 | 1 | NS |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 11 | 3 | NS |

| Malignancy | 10 | 10 | NS |

| Others (AKI, collagen vascular disease) | 8 | 0 | NS |

| Addiction | |||

| Alcohol history | 30 | 4 | 0.006* |

| Tobacco history | 4 | 0 | NS |

| Smoking history | 16 | 2 | 0.045* |

| Metabolic | |||

| Serum sodium (Na), mean | 136.18 | 136.54 | NS |

| Serum potassium (K), mean | 3.98 | 4.13 | NS |

| BUN | 54.84 | 33.03 | 0.001* |

| Creatinine | 1.33 | 0.95 | 0.015* |

| Serum albumin | 3.06 | 3.47 | 0.001* |

| Total bilirubin | 1.55 | 0.77 | 0.014* |

| Serum AST | 48.32 | 41.58 | NS |

| Serum ALT | 37.54 | 30.26 | NS |

| Precipitating factors | |||

| APACHE-II score, mean | 15.72 | 10.90 | 0.001* |

| Medications | |||

| Opioids | 58 | 16 | 0.021* |

| Sedatives | 34 | 0 | 0.001* |

| Steroids | 73 | 12 | 0.001* |

| Anticonvulsant | 76 | 20 | 0.003* |

| Vasopressors/septic | 44 | 6 | 0.001* |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||

| Noninvasive | 37 | 7 | 0.011* |

| Invasive | 77 | 11 | 0.001* |

| ICU bed | |||

| Cubicle | 37 | 7 | NS |

| Noncubicle | 170 | 93 | 0.011* |

| With window | 84 | 45 | NS |

| Without window | 123 | 55 | NS |

| Proximity of ICU bed to nursing station | |||

| Entrance/Exit | 42 | 11 | |

| Washroom | 25 | 7 | |

| Nursing station | 89 | 22 | 0.001* |

Analysis by Chi-square (categorical variables) or t-test (continuous variables).

*p-value <0.05 was significant

With respect to precipitating risk factors, high APACHE score (15.72 vs 10.90, p < 0.001*) and use of medications such as sedatives, steroids, anticonvulsants, opioids, and vasopressors were found significant for the delirium group.

As regards, bed proximity to nursing station and noncubicle bed were significant factors associated with delirium.

The need for mechanical ventilation noninvasive (37 vs 7, p < 0.01*)/invasive (77 vs 11, p < 0.001*) was both associated with delirium and was statistically significant with regard to complications and outcomes, as depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Outcome of delirium

| Complications n (%) | Delirium group (n = 207) | Nondelirium group (n = 100) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Removal of catheters | 74 (35.7) | 0 | 0.001* |

| Aspirations | 41 (19.8) | 1 (1) | 0.001* |

| Reintubations | 22 (10.6) | 0 | 0.001* |

| Decubitus ulcers | 38 (18.4) | 0 | 0.001* |

| Length of stay in the ICU, mean (SD) | 16.27 (12.30) | 5.78 (3.32) | 0.001* |

| Hospital length of stay, mean (SD) | 19.72 (12.89) | 8.07 (3.44) | 0.001* |

| Mortality n (%) | 44 (21.3) | 5 (5) | 0.001* |

Analysis by Chi-square (categorical variables) or t-test (continuous variables).

*p-value <0.05 was significant

Accidental removal of catheters, number of reintubation, decubitus ulcers, and aspirations were significantly more in the delirium group (p < 0.05*).

Increased length of stay in the ICU (mean 16.27 vs 5.78, p < 0.001*) and hospital length of stay (19.72 vs 8.07, p < 0.001*) were significantly associated with delirium. Overall mortality [44/(21.3%) vs 5 (5%), p < 0.01*] was found significant in delirium group.

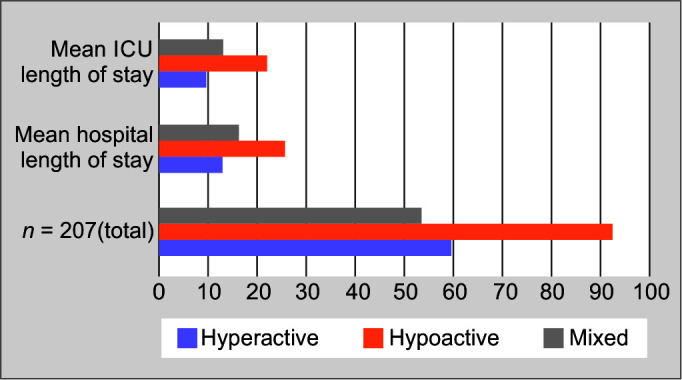

The hypoactive subtype was associated with increased mean length of stay in the ICU as well as hospital length of stay along with concurrent highest mortality of 34.4% compared with other delirium subtypes as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Subtypes of delirium – mean length of hospital and ICU stay

Discussion

Delirium is a prevalent form of acute cognitive impairment in patients in ICUs. The incidence of delirium and its key risk factors should be identified to aid in its prevention.6

There is a wide range (11–70%) of reported delirium occurrence rates across medical and surgical ICUs.7 Differences in delirium incidence rates are likely to be related to patient categories, screening tools, and treatment factors.8

The incidence of delirium was found to be 22.11% among adults admitted to ICUs in the current Indian study. The incidence rate observed is in concurrence with the comprehensive review and meta-regression analysis conducted by Rood et al.,9 reporting a mean incidence of ICU delirium as 29.

The most common subtype of delirium reported in various studies and meta-analysis is hypoactive delirium.10 The present study shows similar results, with predominant hypoactive delirium in (n = 93, 44.9%), followed by hyperactive delirium (n = 60, 29%) and mixed subtype (n = 54, 26.1%) respectively, further higher incidence of hypoactive delirium was associated with increased mean length of ICU and hospital stay and mortality compared with other subtypes.11

The clinical implication of this finding is that hypoactive delirium is “silent,” and its diagnosis is expected to be overlooked in more than two-thirds of patients. These individuals may not be recognized as delirious, missing out on treatment chances, and being at a higher risk of unfavorable outcomes.

The impact of increasing age and high severity of illness scoring on occurrence of delirium is well established in previous studies.7,8 The current finding of delirium being significant with advanced age (mean >58 years) and high APACHE-II score (mean ≥15.72) confirms earlier work. Delirium incidence with a higher proportion in relation to increasing age was also reported in a large retrospective study from Japan.12 Meticulous screening with CAM ICU and RASS scoring system in this group of patients should be done proactively.

Delirium being multifactorial is also associated with various predisposing factors and comorbid conditions. Possible correlation (positive or otherwise) of predisposing factors on the incidence of delirium has been well reported in earlier studies.13 Among the various comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, IHD, CKD, COPD, and chronic liver disease malignancy, in the present study, hypothyroidism was found to have a significant association with delirium.

Hypothyroidism can cause changes in mental status and cognition, which can manifest clinically as delirium. It is evident from various recent case reports.14–16

This implies that specific conditions apart from routine comorbidities must be identified by the treating physician in the ICU to possibly address and avert delirium.

Cigarette smoking and nicotine withdrawal, possibly by upregulation and subsequent desensitization of nicotinic Ach (acetylcholine receptor), with long-term exposure prior to hospital admission and later unoccupied state during abstinence, may contribute to delirium. Habitual use of tobacco in smoking but not in chewing or oral use was found significant in delirium group in the current study. The literature on this subject has produced mixed results. A systematic review by Hseih et al. looked at the association of cigarette smoking with the occurrence of delirium in intensive care patients and concluded that there is insufficient evidence to prove the association.17

Our finding in the study group with higher mean age (58 years) and smoking concurs with the prospective German study, which reported population age >55 years with active smoking associated with delirium.18

Through use of tobacco being a modifiable risk factor, the authors suggest use of nicotine replacement therapy in the form of dermal patch and counseling regarding cessation of use during discharge.

Similarly, habitual positive history of frequent and active alcohol use was also identified as a predisposing factor of delirium in the present study. We did not flag cases of delirium tremens, however, a subtyping of delirium was done in this group. We identified 15 patients who were in hyperactive delirium. Alcohol withdrawal delirium is typically present with hyperactive type. Chronic alcohol use causes complex modulation regulation of Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors and N-methyl D-aspartate receptors, leading to influx of calcium and decreased influx of chloride, leading to excitation and hyperactivity.19

Intensivists should be aware of substance abuse prior to admission as a modifiable predisposing factor of delirium and also should exercise caution while taking history as it is often underreported by the patient himself and his surrogates.

In delirium, there appear to be some connections between pathophysiology and motor behavior. In contrast to substance abuse, metabolic parameters like raised bilirubin, deranged urea, and creatinine lead to hypoactive subtypes. The correlation between higher blood urea nitrogen and creatinine is evident among various prediction models of delirium.20,21

Observations regarding metabolic parameters (higher blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, total bilirubin, and lower albumin level) were statistically significant predisposing factors for delirium in the present research. These findings are in concurrence with a recent Indian study.22 Complex and incompletely understood interplay of neurotransmitters plays a role in the causation of delirium. Screening of these metabolic parameters is suggested in critically ill patients.

Use of therapeutic interventions like steroids, anticonvulsants, opioids, and initiation of mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients as precipitating factors of delirium are well reported in previous studies from India as well as western countries.23

The present study also concurs with these findings as the use of these precipitating factor drug groups mentioned and the use of mechanical ventilation (invasive/noninvasive) were statistically significant in the study group compared with control. A study from Taiwan24 reported that patients on mechanical ventilation who had sepsis or hypoalbuminemia were more likely to experience delirium during the initial stages of their ICU stay and also its association with the need of prolonged mechanical ventilation and mortality, which is in agreement with our observations in the current study. The authors suggest the importance of avoidance and minimization of these interventions, following ventilation protocol of sedation interruption and wise choice of pharmacotherapeutic agent, by differentiating the need of analgesia or sedation in individual patients and newer agents like dexmedetomidine for prevention of the delirium.

The effect of acoustical profiles of different hospital units and patient's environment has been studied and reported in previous studies.25 We also observed that patients in noncubicle and bed proximity to the nursing station were associated with delirium.

Noise level and disturbance of sleep pattern could play a role as a predisposing factor for occurrence of delirium.26 We did not quantify and collect the sound-level data differences in cubicle, noncubicle bed, and proximity to the nursing station in various shifts. Evidence suggests monitoring of noise levels in the ICU as an important modifiable factor.27

Finally, evidence regarding complications and the negative impact of delirium on outcome is quite evident.28 Hyperactive delirium may lead to accidental removal of devices in critically ill patients.29 Accidental removal of catheters, reintubation, decubitus ulcers, and aspirations were the significant complications observed in the present study along with the clinical outcome of the increased length of stay in the ICU, hospital, and mortality. These findings are similar to the one reported in meta-analysis by Zhang et al. in critically ill patients.30

The strength of the present Indian study is a single-center prospective clinical observational noninterventional study with a large sample study population of 936 critically ill patients from the Indian ICU. In addition, diagnosis of delirium was made with use of a standard screening tool along with additional confirmation by psychiatrists, while most of the previous studies relied on the screening tool alone.

It is also having some limitations, recent effect of the pandemic cannot be underestimated, owing to its impact on monitoring, patient care, increased use of sedatives, and restricted family visits.

Haloperidol, olanzapine, and dexmedetomidine are currently the main medications used at our center to control delirium. Since this was not an interventional trial, we did not assess the records of the medication used for this particular patient population. Doses of sedatives and steroids were not recorded, so we cannot determine the therapeutic relationship with delirium. Finally, we did not assess the long-term outcomes to detect persistent cognitive impairment. Hence, a long-term follow-up study is needed.

Conclusion

Delirium is highly prevalent in Indian ICUs with significant impact on the length of stay and mortality. Hypoactive delirium subtype is more common. Implementation of CAM-ICU bedside screening tool along with psychiatrist confirmation will strengthen identification and help early recognition. Prevention by identification of incidence and risk factors is the first step toward the goal of future delirium-free ICU.

Orcid

Anand Mohanlal Tiwari https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9791-8365

Kapil Gangadhar Zirpe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8140-727X

Afroz Ziyaulla Khan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3170-496X

Sushma Kirtikumar Gurav https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6875-2071

Abhijit Manikrao Deshmukh https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5602-291X

Prasad Bhimrao Suryawanshi https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7306-8434

Upendrakumar S Kapse https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5279-4485

Prajkta Prakash Wankhede https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3620-3390

Shrirang Nagorao Bamne https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1128-4793

Abhaya Pramodrao Bhoyar https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0460-3162

Ria Vishal Malhotra https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1026-0274

Santosh M Sontakke https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6528-8573

Pankaj B Borade https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2436-6341

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: Dr Kapil Gangadhar Zirpe is associated as the Editorial Board member of this journal and this manuscript was subjected to this journal's standard review procedures, with this peer review handled independently of this editorial board member and his research group.

References

- 1.Marcantonio ER. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(15):1456–1466. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1605501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson JE, Mart MF, Cunningham C, Yahya S, Girard TD, MacLullich AMJ, et al. Delirium (Primer). Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):90. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00223-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damluji A, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015:350. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krewulak KD, Stelfox HT, Leigh JP, Ely EW, Fiest KM. Incidence and prevalence of delirium subtypes in an adult ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):2029–2035. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dziegielewski C, Skead C, Canturk T, Webber C, Fernando SM, Thompson LH, et al. Delirium and associated length of stay and costs in critically ill patients. Crit Care Res Pract. 2021;2021:6612187. doi: 10.1155/2021/6612187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan Y, Yan J, Jiang Z, Luo J, Zhang J, Yang K. Incidence, risk factors, and cumulative risk of delirium among ICU patients: A case-control study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6(3):247–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouimet S, Kavanagh BP, Gottfried SB, Skrobik Y. Incidence, risk factors and consequences of ICU delirium. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(1):66–73. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, Thompson J, Pun BT, Morris JA, Jr, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for development of delirium in surgical and trauma ICU patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(1):34–41. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31814b2c4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rood P, Huisman-de Waal G, Vermeulen H, Schoonhoven L, Pickkers P, van den Boogaard M. Effect of organisational factors on the variation in incidence of delirium in intensive care unit patients: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Aust Crit Care. 2018;31(3):180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson JF, Pun BT, Dittus RS, Thomason JW, Jackson JC, Shintani AK, et al. Delirium and its motoric subtypes: A study of 614 critically ill patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jayaswal AK, Sampath H, Soohinda G, Dutta S. Delirium in medical intensive care units: Incidence, subtypes, risk factors, and outcome. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(4):352–358. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_583_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kubota K, Suzuki A, Ohde S, Yamada U, Hosaka T, Okuno F, et al. Age is the most significantly associated risk factor with the development of delirium in patients hospitalized for more than five days in surgical wards: Retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2018;267(5):874–877. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aldemir M, Özen S, Kara IH, Baç B. Predisposing factors for delirium in the surgical intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2001;5(5):265–270. doi: 10.1186/cc1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilješ AP. Case report: Delirium and hypothyroidism. Acta Med-Biotech. 2021;14(1) doi: 10.18690/actabiomed.216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernández-Sandí A, Quirós-Baltodano D, Oconitrillo-Chaves M. Delirium, caused by suspending treatment of hypothyroidism. Ment Illn. 2016;8(2):6787. doi: 10.4081/mi.2016.6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris MS, Mathew RJ, Webb WW. Delirium associated with lithium-induced hypothyroidism: A case report. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(3):355–356. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh SJ, Shum M, Lee AN, Hasselmark F, Gong MN. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for delirium in hospitalized and intensive care unit patients. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(5):496–503. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201301-001OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hessler JB, Brönner M, Etgen T, Gotzler O, Förstl H, Poppert H, et al. Smoking increases the risk of delirium for older inpatients: A prospective population-based study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(4):360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steiner LA. Postoperative delirium. Part 1: Pathophysiology and risk factors. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(9):628–636. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e328349b7f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller MO. Evaluation and management of delirium in hospitalized older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(11):1265–1270. 19069020 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, Hurst LD, Tinetti ME. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):474–481. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-6-199309150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagari N, Babu MS. Assessment of risk factors and precipitating factors of delirium in patients admitted to intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital. Br J Med Pract. 2019;12(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma A, Malhotra S, Grover S, Jindal SK. Incidence, prevalence, risk factor and outcome of delirium in intensive care unit: a study from India. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(6):639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin S-M, Huang C-D, Liu C-Y, Lin H-C, Wang C-H, Huang P-Y, et al. Risk factors for the development of early-onset delirium and the subsequent clinical outcome in mechanically ventilated patients. J Crit Care. 2008;23(3):372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harari RM, Prasad MG. Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE and NOISE-CON Congress and Conference. 2. Vol. 248. Institute of Noise Control Engineering; 2014. Sep 8, The relationship between patients and delirium as affected by hospital acoustics. pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaney LJ, Litton E, Van Haren F. The nexus between sleep disturbance and delirium among intensive care patients. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2021;33(2):155–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goeren D, John S, Meskill K, Iacono L, Wahl S, Scanlon K. Quiet time: A noise reduction initiative in a neurosurgical intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurse. 2018;38(4):38–44. doi: 10.4037/ccn2018219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Junior MM, Kumar A, Kumar P, Gupta P. Assessment of delirium as an independent predictor of outcome among critically ill patients in intensive care unit: A prospective study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2022;26(6):676–681. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tilouche N, Hassen MF, Ali HB, Jaoued O, Gharbi R, El Atrous SS. Delirium in the intensive care unit: Incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018;22(3):144–149. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_244_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Pan L, Ni H. Impact of delirium on clinical outcome in critically ill patients: A meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(2):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]