Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), as well as their concurrence, represent the most common types of cognitive dysfunction. Treatment strategies for these two conditions are quite different; however, there exists a considerable overlap in their clinical manifestations, and most biomarkers reveal similar abnormalities between these two conditions.

Purpose

To evaluate the potential of cerebral oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) as a biomarker for differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and VCI. We hypothesized that in Alzheimer’s disease OEF will be reduced (decreased oxygen consumption due to decreased neural activity), while in vascular diseases OEF will be elevated (increased oxygen extraction due to abnormally decreased blood flow).

Study Type

Prospective cross-sectional.

Population

Sixty-five subjects aged 52–89 years, including 33 mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 7 dementia, and 25 cognitively normal subjects.

Field Strength / Sequence

3T T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging (FLAIR).

Assessment

OEF, consensus diagnoses of cognitive impairment, vascular risk factors (such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, smoking, and obesity), cognitive assessments, and cerebrospinal fluid concentration of amyloid and tau.

Statistical Tests

Multiple linear regression analyses of OEF with diagnostic category (normal, MCI, or dementia), vascular risks, cognitive performance, amyloid and tau pathology.

Results

When evaluating the entire group, OEF was found to be lower with more severe cognitive impairment (β=−2.70±1.15, T=−2.34, P=0.02), but was higher with greater vascular risk factors (β=1.36±0.55, T=2.48, P=0.02). Further investigation of the subgroup of participants with low vascular risks (N=44) revealed that lower OEF was associated with worse cognitive performance (β=0.04±0.01, T=3.27, P=0.002) and greater amyloid burden (β=92.12±41.23, T=2.23, P=0.03). Among cognitively impaired individuals (N=40), higher OEF was associated with greater vascular risk factors (β=2.19±0.71, T=3.08, P=0.004).

Data Conclusion

These findings suggest that OEF is differentially affected by Alzheimer’s disease and VCI pathology and may be useful in etiology-based diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

Keywords: oxygen extraction fraction, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular cognitive impairment, vascular risk factors, CSF amyloid

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment (VCI), as well as their concurrence, represent the most common types of cognitive dysfunction (1). Treatment strategies for these two conditions are very different. However, there exists a considerable overlap in clinical symptoms and neuroimaging features between them (2). Indeed, virtually all proposed dementia biomarkers to-date showed similar alterations in Alzheimer’s disease and VCI (2). Therefore, we still lack effective tools for differential diagnosis between these two conditions, which is important for treatment development and planning.

Cerebral oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) reflects a delicate balance between vascular (e.g. blood supply) and neural (e.g. oxygen consumption) function (3,4). In large-vessel diseases, such as carotid artery occlusion, OEF is a valuable biomarker, and a higher OEF predicts a greater risk for stroke (5). This is because, in ischemic tissue, there is insufficient blood supply relative to metabolic demand; thus, the brain has to extract a higher fraction of oxygen from the incoming blood. In Alzheimer’s disease, on the other hand, tissue metabolic demand is diminished secondary to amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration (6), while vascular function, e.g. cerebrovascular reactivity (7), is relatively intact. Therefore, we hypothesized that in Alzheimer’s disease OEF will be reduced (decreased oxygen consumption due to decreased neural activity) while in vascular diseases OEF will be elevated (increased oxygen extraction due to abnormally decreased blood flow).

OEF is traditionally very difficult to measure, requiring the use of a short (2 min) half-life radiotracer, 15O, with continuous arterial blood sampling inside a positron emission tomography (PET) scanner (8). In this work, we used a T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI technique that can provide a global measurement of OEF based on the association between blood T2 and oxygenation (9,10). The accuracy of TRUST global OEF quantification has recently been validated with gold standard 15O PET (11). Advantages of the TRUST technique over 15O PET are that it is radiation-free, rapid, non-invasive (without injecting any contrast agent), and scalable (can be used on any 3T MRI scanner without special hardware) (12,13).Our aim was to examine the relationship of OEF, as measured by MRI, to Alzheimer’s pathology and vascular risk factors in a group of cognitively impaired patients with mixed Alzheimer’s and vascular pathology.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Consensus Diagnosis

The study protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects provided written informed consent before participating in this study. Elderly subjects (>50 years old) were recruited from the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Comprehensive Diabetes Center and local outpatient clinics, between April 2017 and July 2018. Subjects were excluded if they had any MRI contraindications (e.g. claustrophobia), major psychiatric disorders (e.g. severe depression), history of cancers, strokes, heart attacks or head traumas, or other neurological diseases (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease).

Current standard diagnoses of cognitive impairment are largely based on symptoms and it is often difficult to determine the exact etiology, i.e., whether the impairment is caused by Alzheimer’s disease or VCI (14). Therefore, the participants in this study were first classified in accordance with this standard practice. Specifically, based on clinical summaries and neuropsychological assessments, each subject was given a diagnosis of cognitively normal, MCI, or dementia, through a consensus diagnosis among a neuropsychologist (M.A., 41-year experience), a gerontologist (S.Y., 32-year experience) and a psychiatrist (P.R., 35-year experience). The diagnostic procedures followed recommendations of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup (14). Information about disease etiology was obtained from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) assay and vascular risk determination, as detailed below.

Cognitive Assessments

All subjects underwent a detailed battery of neuropsychological tests, covering four cognitive domains: [1] verbal episodic memory tested by Logical Memory Delayed-recall (15) and Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Recall over Trials 1–5 (16); [2] executive function tested by Digit Span Backwards (15), Trial Making Test Part B (17), Digit Symbol Test (18), and Stroop Color-Word Score (19); [3] processing speed tested by Trial Making Test Part A (17) and Stroop Color and Word Scores (19); and [4] language tested by Multilingual Naming Test (20), Letter (F & L), and Category (animal, vegetables) Fluency Tasks (21).

Cognitive scores were created for each domain by computing a z-score for each test score and then averaging the z-scores within each domain. As an index of overall cognitive function, a composite cognitive score was calculated by averaging the z-scores of the four domains.

Amyloid and Tau Pathology Assessed from CSF

In a subset of subjects (N=43), CSF samples were collected through lumbar puncture. Concentrations (in picograms/ml) of CSF β-amyloid-42 (Aβ42), β-amyloid-40 (Aβ40), total tau, and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) were measured using electrochemiluminescence Lumipulse assays on the Fujirebio platform in a single batch (Fujirebio Lumipulse, Malvern, PA). The Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was used as an index for amyloid pathology (22). Total tau and p-tau were used to assess tau pathology.

Vascular Risk Assessments

Five vascular risk factors, based on self-reported medical history interview, were considered, as proposed in the literature (23). The vascular risk factors were coded as binary variables: [1] hypertension history (1=recent, 0=remote/absent), [2] hypercholesterolemia history (1=recent, 0=remote/absent), [3] diabetes history (1=recent, 0=remote/absent), [4] smoking history (1 if smoked >100 cigarettes in his/her life, 0 if not), and [5] body-mass-index (BMI; 1 if BMI>30, 0 if not) (23). As an index for overall vascular risks, a vascular risk score (VRS), ranging from 0 to 5, was created by summing the five binary-coded factors.

MRI Experiments

All subjects were scanned on a Philips 3T Achieva system (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). A 32-channel receive head coil was used, and the body coil was used for transmission. Foam padding was placed around the head of the subject to minimize motion during the scan.

Each subject underwent a TRUST scan and a fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) scan, among other sequences. Sequence parameters of TRUST were: single slice, axial field-of-view (FOV) = 220×220×5 mm3, voxel size = 3.44×3.44×5 mm3, repetition time (TR) = 3 s, inversion time (TI) = 1.02 s, echo time (TE) = 3.6 ms, labeling slab thickness = 100 mm, gap = 22.5 mm, four effective echo times (eTEs) = 0, 40, 80 and 160 ms, and total scan time = 1.2 min. The imaging slice of TRUST MRI was placed to be parallel to the anterior-commissure–posterior-commissure line and 20mm above sinus confluence, following previous reports (13). Test-retest studies with subject repositioning showed that the OEF results are minimally dependent on the slice location (12). Sequence parameters of FLAIR were: 3D acquisition, sagittal FOV = 240 × 240 × 165 mm3, voxel size = 1.1×1.1×1.1 mm3, TR = 4.8 s, TI = 1.65 s, TE = 276 ms, and total scan time = 4.2 min.

During the TRUST MRI scan, a nasal canula (Model 4000F-7, Salter Labs, Arvin, CA, USA) was used to sample the exhaled gas, and the end-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) of the subject was recorded using a capnograph device (NM3 Respiratory Profile Monitor, Model 7900, Philips Healthcare, Wallingford, CT, USA).

MRI Data Processing

The processing of the TRUST MRI data followed previous literature (9), using in-house MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) scripts. Briefly, after motion correction, pairwise subtraction between labeled and control images was performed to produce difference images, on which a preliminary region-of-interest (ROI) was drawn to encompass the superior sagittal sinus (SSS). Four voxels with the highest signal intensities inside the preliminary ROI were selected as the final mask, and the signals within the final mask were spatially averaged. By fitting the averaged blood signals as a mono-exponential function of eTEs, T2 of the blood was obtained and then converted to Yv through known calibration models (10). The T2-Yv conversion took into account the subject’s hematocrit level, which was measured from each subject through a blood draw. Since SSS drains the majority of the cerebral cortex, TRUST MRI provides an assessment of the global OEF of the brain. As a metric of the uncertainty of OEF measurement, the width of the 95% confidence interval of the transverse relaxation rate (1/T2 or R2) was calculated from the mono-exponential fitting procedure and was referred to as ΔR2. Data with ΔR2 ≥ 5Hz were considered to have poor quality and were excluded from statistical analyses.

The global OEF was calculated as:

| (1) |

where Ya is the arterial oxygenation and was assumed to be 98% for all subjects in this study (24).

A previous study showed that normal variations in OEF are largely (~50%) attributed to the subjects’ EtCO2 levels (25). Therefore, to reduce physiological variations, we measured EtCO2 of each subject during the TRUST MRI scan and used it to correct OEF by:

| (2) |

where OEFraw is the OEF value before correction, is the averaged EtCO2 across subjects. The coefficient α was obtained by linear regression between OEF and EtCO2 across subjects (Supplementary Figure S1) and was found to be −0.87±0.16%/mmHg (P=2×10−6). The corrected OEF were used in all subsequent analyses.

FLAIR MRI images were reviewed by a board-certified neuroradiologist (J.P., 28-year experience) and confirmed by two independent observers (D.J., 8-year experience of MRI and Z.L., 6-year experience of MRI) to evaluate white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in deep white matter and periventricular white matter, respectively, using the Fazekas scale (26) (see Supplementary Figure S2 for examples). The final Fazekas score for each subject was the average of the deep white matter and periventricular white matter scores, ranging from 0 to 3.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Matlab R2016b (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, 2016). One-way ANOVA analyses were used to examine whether there were differences in age, sex, VRS, education, or EtCO2 among the three diagnostic groups.

To evaluate the association of OEF with diagnostic category and vascular risks, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted using OEF as the dependent variable and VRS and diagnosis as the independent variables. The diagnostic category was treated as a categorical variable (0=normal, 1=MCI, 2=dementia). A Diagnosis×VRS interaction term was also tested. If a significant interaction effect was observed, we then divided the subjects into subgroups based on VRS or diagnosis and conducted separate analyses. We first divided the subjects into a low-VRS (VRS≤2) and a high-VRS (VRS>2) subgroup, and investigated the association between OEF and diagnosis. We then divided the subjects into a normal and an impaired (MCI or dementia) subgroup, and examined the association between OEF and VRS.

To investigate the relationship of OEF with cognition, we used linear regressions, in which the cognitive test scores were dependent variables (separately for composite cognitive score and the four domain-specific scores), and OEF was the independent variable.

We also assessed the associations of OEF with amyloid, tau, and WMH using linear regressions, in which OEF was the dependent variable and Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, total tau, p-tau, or Fazekas score was the independent variable (separately for each parameter).

In all linear regression analyses, age and sex were covariates. In regressions involving cognitive functions, education was also added as a covariate. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. For analyses performed separately for each cognitive domain, Bonferroni correction was conducted.

Results

Characteristics of Participants

Ninety-two subjects were screened. Twenty-one subjects were excluded due to MRI contraindications (N = 6), major psychiatric disorders (N = 5), history of cancers (N = 1), stroke (N = 1), heart attack (N = 1) or head traumas (N = 3) and other neurological diseases (N = 4). Among the 71 recruited subjects (69.6±7.5 years old, 32 males and 39 females), six had poor OEF data quality (ΔR2≥5Hz) and were excluded from further analyses. In the remaining 65 subjects, 25 were diagnosed as cognitively normal, 33 as MCI, and 7 as dementia. The characteristics of the included subjects are listed in Table 1. One-way ANOVA analyses found no significant differences in age (P=0.052), sex (P=0.11), VRS (P=0.17), education (P=0.07), or EtCO2 (P=0.48) among the three diagnostic groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Whole group | Normal | MCI | Dementia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 65 | 25 | 33 | 7 |

| Age (years) | 69.1±7.2 | 69.5±6.7 | 67.6±6.8 | 74.7±8.7 |

| Sex (male) | 29 (44.6%) | 7 (28.0%) | 18 (54.5%) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Composite cognitive score | 0.1±0.6 | 0.6±0.3 | −0.1±0.4 | −0.7±0.6 |

| VRS | 2.0±1.3 | 1.7±1.2 | 2.1±1.3 | 2.7±1.6 |

| OEF (%) | 45.5±6.1 | 46.9±5.1 | 44.9±6.6 | 43.2±6.9 |

| Fazekas score | 1.6±0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | 1.6±0.7 | 2.0±1.0 |

| Education (years) | 16.2±3.2 | 16.2±2.6 | 15.6±3.6 | 18.6±2.0 |

| EtCO2 (mmHg) | 37.7±4.6 | 36.8±4.6 | 38.2±4.5 | 38.4±5.6 |

| N with CSF samples | 43 | 18 | 23 | 2 |

| Aβ42 (picograms/ml) | 1465±612 | 1595±451 | 1311±566 | 2059±1910 |

| Aβ40 (picograms/ml) | 12654±4266 | 13504±3204 | 11213±3352 | 21574±11080 |

| Aβ42 / Aβ40 | 0.116±0.030 | 0.120±0.026 | 0.117±0.032 | 0.084±0.046 |

| Total tau (picograms/ml) | 310±130 | 305±111 | 290±118 | 601±136 |

| p-tau (picograms/ml) | 43±20 | 42±15 | 40±18 | 94±1 |

MCI: mild cognitive impairment; VRS: vascular risk score; EtCO2: end-tidal carbon dioxide; OEF: oxygen extraction fraction, corrected for EtCO2; Aβ42: β-amyloid-42; Aβ40: β-amyloid-40; p-tau: phosphorylated tau.

Note: Unless otherwise specified, data are mean ± standard deviation. Data in parentheses are percentages.

Dependence of OEF on Diagnosis and VRS

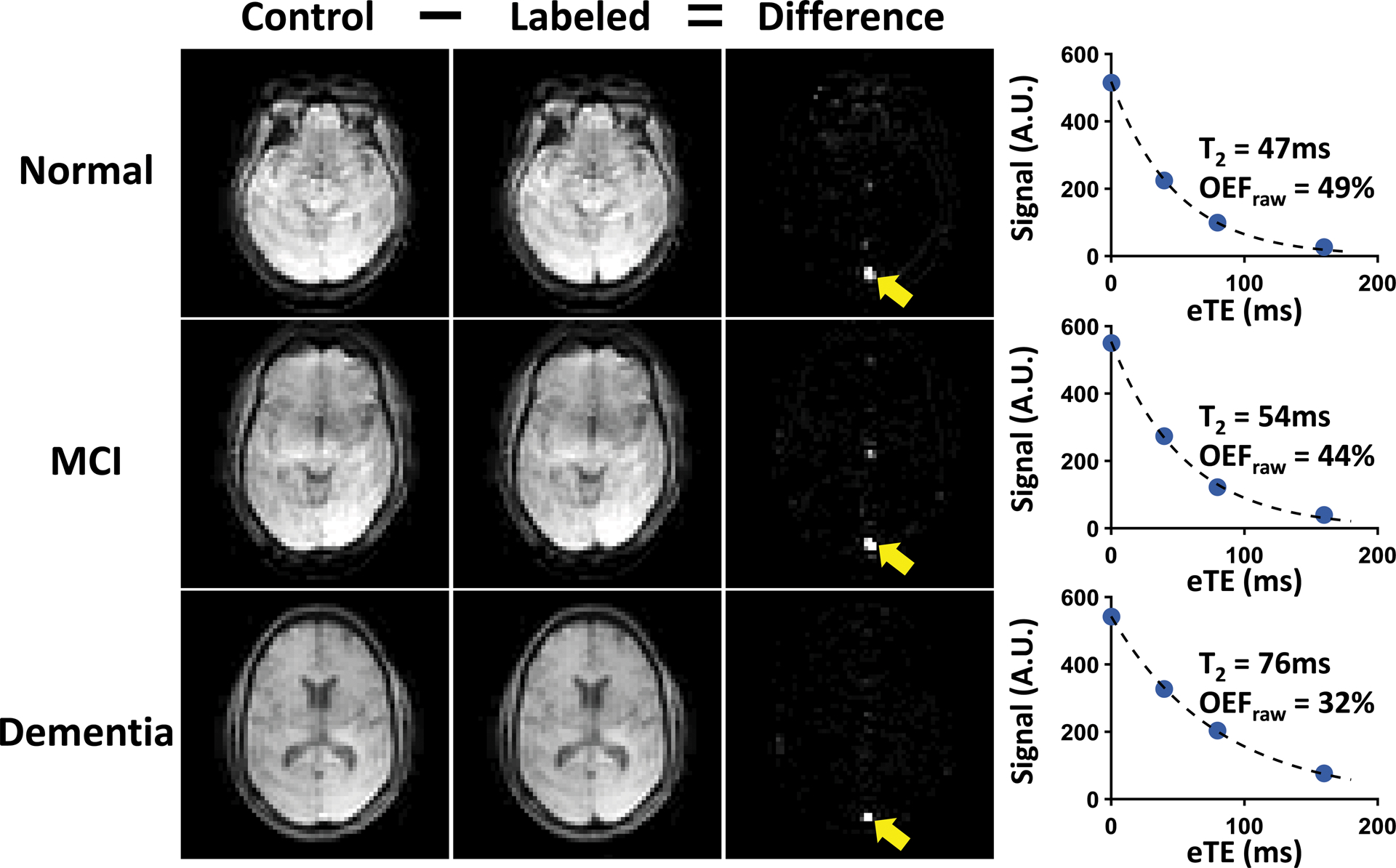

Representative TRUST OEF data are shown in Figure 1. Multi-linear regression analysis (Table 2, Model 1) revealed that OEF was significantly associated with diagnostic category (β=−2.70±1.15, T=−2.34, P=0.02). Specifically, OEF was lower in patients with MCI and dementia. On the other hand, OEF was higher in individuals with worse (higher) VRS (β=1.36±0.55, T=2.48, P=0.02). Additionally, OEF increased with age (β=0.25±0.10, T=2.50, P=0.02), consistent with previous reports (24,27). OEF was not related to sex (P=0.69). We also examined the relationship between OEF and each vascular risk factor separately, and found that OEF had a positive but insignificant association with each factor (P>0.4, Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1:

Representative TRUST OEF data. Representative data of normal (top row), MCI (second row) and dementia (bottom row) subjects are shown. Subtraction between control (first column) and labeled (second column) images yields strong venous blood signal in the superior sagittal sinus (yellow arrows) in the difference images (third column). The scatter plots on the far right show venous signal as a function of effective echo times (eTEs). Fitted venous blood T2 and the corresponding OEF values (before correction) are also shown.

Table 2.

Multi-linear regression models between OEF, diagnosis and VRS in the whole group (N=65). In all models, OEF was the dependent variable, the independent variables are listed below.

| Independent variables | β±SE | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Diagnosis | −2.70±1.15 | 0.02 |

| VRS | 1.36±0.55 | 0.02 | |

| Age | 0.25±0.10 | 0.02 | |

| Sex | 0.59±1.48 | 0.69 | |

| Model 2 | Diagnosis | −2.99±1.13 | 0.01 |

| VRS | 1.19±0.54 | 0.03 | |

| Diagnosis×VRS | 1.69±0.78 | 0.04 | |

| Age | 0.22±0.10 | 0.03 | |

| Sex | −0.03±1.46 | 0.99 |

β: standardized beta coefficient; SE: standardized error; VRS: vascular risk score; OEF: oxygen extraction fraction.

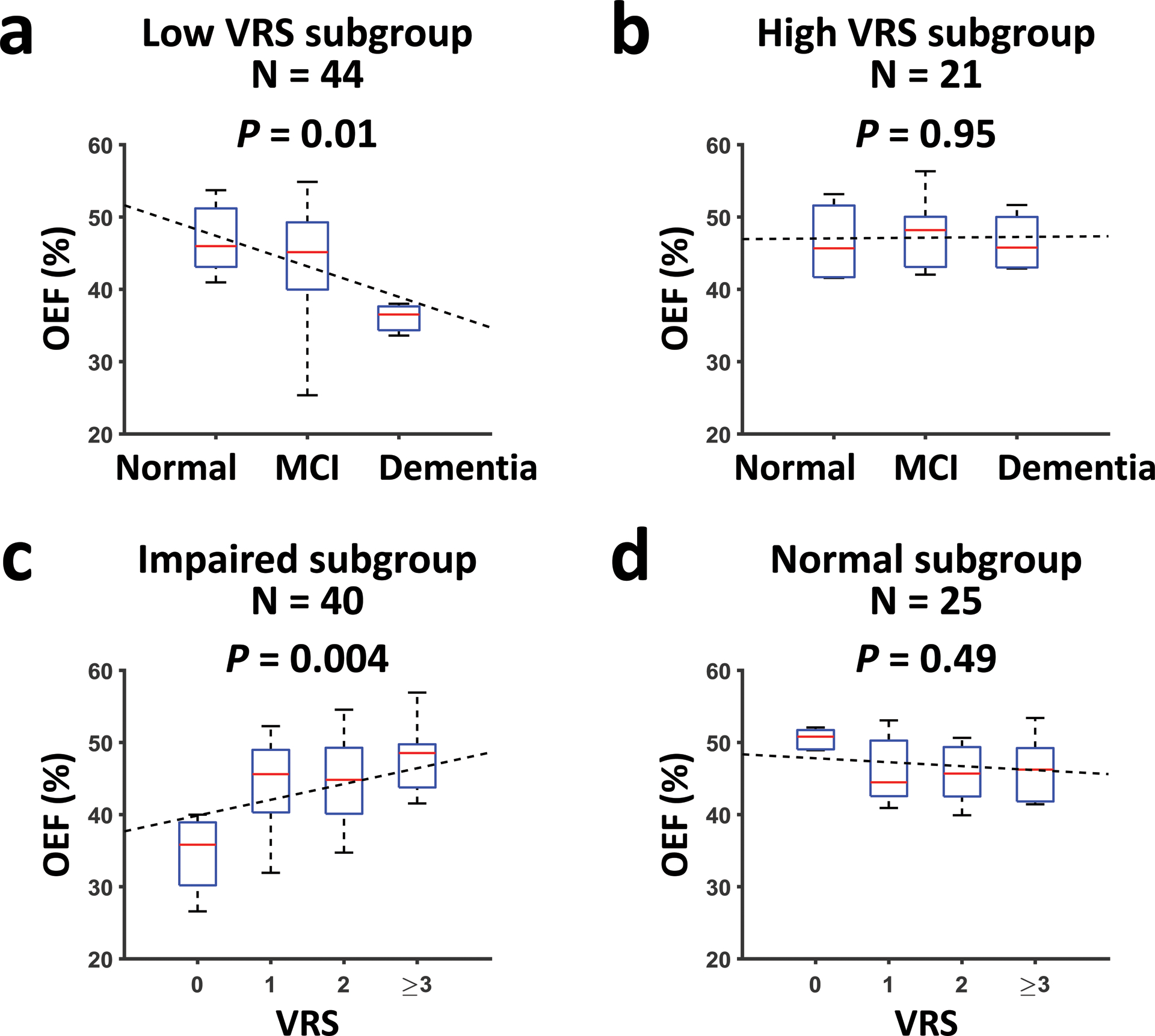

When further adding the Diagnosis×VRS interaction term (Table 2, Model 2), a significant interaction effect was observed (β=1.69±0.78, T=2.15, P=0.04). Therefore, we divided the subjects into subgroups and conducted further analyses for each subgroup. We first divided the subjects by VRS. Supplementary Table S2 lists the characteristics of subjects in the low-VRS and high-VRS subgroups, showing no significant difference in age (P=0.76) or sex (P=0.74) between the two subgroups. As shown in Figure 2a, in the low-VRS subgroup (N=44), OEF was inversely associated with clinical diagnosis (β=−4.22±1.62, T=−2.60, P=0.01). On the other hand, as shown in Figure 2b, in the high-VRS subgroup (N=21), OEF was not associated with clinical diagnosis (P=0.95).

Figure 2:

OEF values in participants stratified by diagnosis and VRS. (a) The relationship between OEF and diagnostic category in participants with low VRS. (b) The relationship between OEF and diagnostic category in participants with high VRS. (c) The relationship between OEF and VRS in participants with cognitive impairment (MCI or dementia). (d) The relationship between OEF and VRS in cognitively normal participants. All figures have been adjusted for age and gender. Median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum of the data points are shown in the box plots. Dashed lines show the fitted linear regression lines.

Next, we separated the subjects by clinical diagnosis. As illustrated in Figure 2c, among cognitively impaired individuals (MCI or dementia, N=40), OEF was positively associated with VRS (β=2.19±0.71, T=3.08, P=0.004). OEF was not associated with VRS (P=0.49) in the normal subgroup (N=25, Figure 2d).

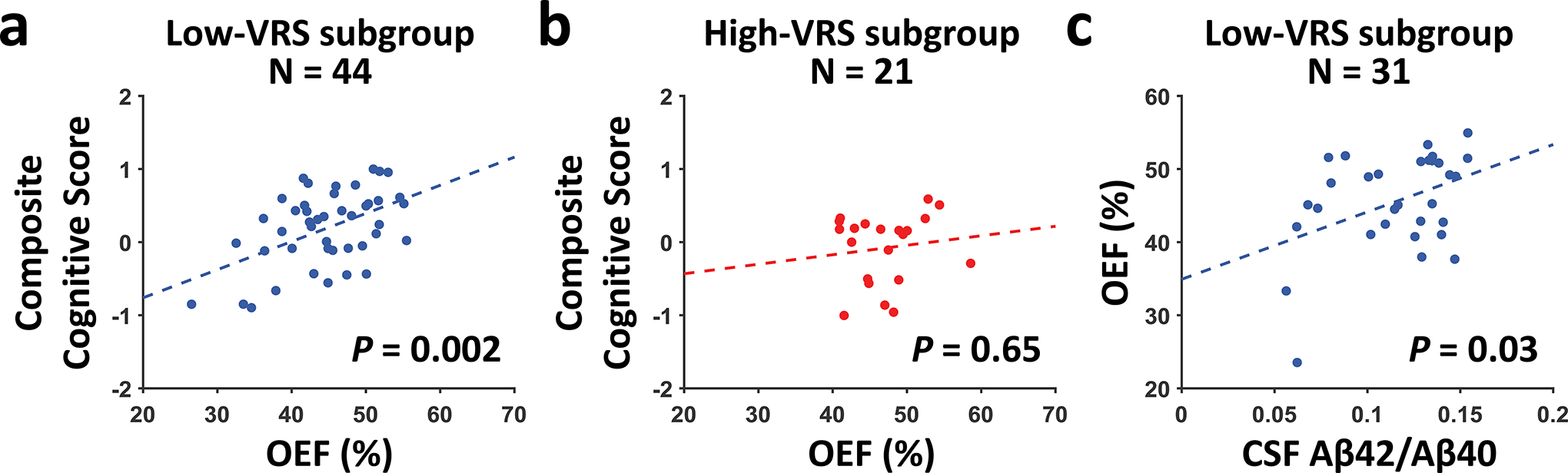

Relationship of OEF with Cognition, Amyloid and Tau Pathology, and WMH

When examining the relationship between OEF and cognitive function in the whole group (Table 3), higher OEF was associated with better composite cognitive score (N=65, β=0.03±0.01, T=2.23, P=0.03). For individual cognitive domains, OEF was positively associated with processing speed (β=0.04±0.02, T=2.62, P=0.04) but not associated with the other domain scores (with language score showing an effect before Bonferroni correction) (Table 3). We further investigated the association between cognition and OEF in the low-VRS and high-VRS subgroups, respectively. As shown in Figure 3a, in the low-VRS subgroup (N=44), composite cognitive score was positively associated with OEF (β=0.04±0.01, T=3.27, P=0.002). For individual domain scores, in the low-VRS subgroup (Table 4), OEF was positively associated with processing speed (β=0.07±0.02, T=3.94, P=0.001), but not with the other domain scores. No association between OEF and cognition was found in the high-VRS subgroup (N=21, P=0.65 for composite cognitive score, Figure 3b, Supplementary Table S3).

Table 3.

Multi-linear regression between OEF and cognition in the whole group (N=65). In all models, OEF was the independent variable, age, sex and education were covariates.

| Dependent variable | 1β±SE for OEF | P-value | 2Corrected P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite cognitive score | 0.03±0.01 | 0.03 | 3N.A. |

| Processing speed, z score | 0.04±0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Episodic memory, z score | 0.02±0.02 | 0.32 | 0.79 |

| Executive function, z score | 0.02±0.01 | 0.25 | 0.69 |

| Language, z score | 0.03±0.01 | 0.045 | 0.17 |

β: standardized beta coefficient; SE: standardized error; OEF: oxygen extraction fraction.

Corrected P-value: P-value with Bonferroni correction.

N.A.: no correction was applied because we only had one composite cognitive score in this study.

Figure 3:

Relationship of OEF with composite cognitive score and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. (a) Scatter plots between composite cognitive score and OEF in the low-VRS subgroup. (b) Scatter plots between composite cognitive score and OEF in the high-VRS subgroup. (a) and (b) have been adjusted for age, gender, and education. (c) Scatter plot between OEF and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in the low-VRS subgroup, adjusted for age and sex. Dashed lines indicate the fitted linear regression lines.

Table 4.

Multi-linear regression models between OEF and cognition in the low-VRS subgroup (N=44). In all models, OEF was the independent variable, age, sex, and education were covariates.

| Dependent variable | 1β±SE for OEF | P-value | 2Corrected P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite cognitive score | 0.04±0.01 | 0.002 | 3N.A. |

| Processing speed, z score | 0.07±0.02 | 0.0003 | 0.001 |

| Episodic memory, z score | 0.02±0.02 | 0.17 | 0.54 |

| Executive function, z score | 0.03±0.01 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Language, z score | 0.03±0.01 | 0.07 | 0.24 |

β: standardized beta coefficient; SE: standardized error; OEF: oxygen extraction fraction, corrected for EtCO2.

Corrected P-value: P-value with Bonferroni correction.

N.A.: no correction was applied because we only had one composite cognitive score in this study.

In the subset of subjects with CSF measurements (N=43), we found a trend of positive association between OEF and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (P=0.06). Further analysis revealed that in the low-VRS subgroup (N=31), OEF was positively associated with CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (β=92.12±41.23, T=2.23, P=0.03), as shown in Figure 3c. No association between OEF and CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio was observed in the high-VRS subgroup (N=12, P=0.71). Similar analyses with total tau and p-tau yielded no significant effects on OEF (P=0.37 for total tau, and P=0.57 for p-tau).

We found no association between OEF and Fazekas score (P=0.86).

Discussion

It is recognized that pathological markers, such as CSF assay or amyloid-PET imaging, by themselves are not sufficient to establish a clinical diagnosis of cognitive impairment, as approximately 20% of cognitively normal elderly individuals are amyloid-positive (28). Therefore, complementary markers indexing brain function are urgently needed (29–31). OEF reflects the brain’s oxygen extraction ability and thus may be a useful diagnostic marker. Several studies have investigated the association of OEF with cognitive impairment, but the results were mixed (7,8,32,33). An early study by Frackowiak et al. found no changes of OEF in patients with either Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia (8). The lack of alterations of OEF in vascular dementia was also reported by a later study in patients with Binswanger’s disease (32). In patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease, Nagata et al. reported an increased OEF, which was, however, attributed by the authors to a possible microvascular disturbance (33). Our study reconciles these discrepancies by showing that OEF is altered in individuals with MCI or dementia, but the change is dependent on the sub-types of the impairment. If the impairment is primarily attributed to Alzheimer’s disease, OEF is diminished due to reduced brain metabolism (7). This notion is further supported by our observation that, in individuals with low vascular risks, lower OEF was associated with worse cognitive performance and lower CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio (corresponding to a higher brain amyloid burden). These findings are consistent with a previous study which showed that, in a cohort carefully selected to exclude patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases, MCI patients had lower OEF than age-matched controls (7).

On the other hand, in patients with vascular diseases, OEF is unchanged or slightly elevated. When examining the entire group, OEF was higher in individuals with worse VRS. This effect was particularly prominent in the cognitively impaired group. This is because higher vascular risks are postulated to be associated with poorer brain perfusion, thus a higher fraction of oxygen must be extracted from the blood to meet the neuron’s metabolic needs (8,32).

Findings from the present study suggest that OEF has several potential utilities in clinical diagnosis of dementia. First, for patients whose clinical and neuropsychological assessments (14) have determined that the patient is cognitively impaired but the etiology is unclear, OEF can be used to differentiate the likelihood of Alzheimer’s versus vascular sub-type. Second, if the patient has no vascular risks (e.g. hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes) but has cognitive complaints, OEF can be used to determine if the patient is likely having MCI. Third, if the patient has genetic or pathological risks for Alzheimer’s disease, OEF can be used to determine if they may have early brain dysfunction. For example, a previous study showed that even among cognitively normal individuals, the carriers of the apolipoprotein-E4 gene, a major genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, manifest diminished OEF (34).

It is known that breakdown of blood-brain-barrier (BBB) plays an important role in cognitive impairment (2). For example, a recent study showed that BBB leakage of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β, which indicates loss of pericytes, predicts cognitive impairment independently from Alzheimer’s pathology (35). Since it has been reported that pericyte degeneration diminishes cerebral blood flow (36), an elevated OEF is expected. The relationship between BBB breakdown and OEF shall be further elucidated in future research.

Limitations

First, our sample size (N=65) is modest. Second, we used a cross-sectional design, while longitudinal design is important to test the predictive value of OEF. Third, the consensus diagnosis used in our study, while being the current clinical standard, could not determine the exact etiology of the cognitive impairment, thus we did not have a gold standard of whether the subjects were having Alzheimer’s disease or VCI. Fourth, the present study has primarily accounted for amyloid deposition in the brain parenchyma and considered amyloid and vascular disease as separate underlying causes of dementia. However, amyloid is also known to accumulate in cerebral vessels, known as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). If CAA causes vessel narrowing and reduces blood flow, OEF is expected to increase, which is opposite to the effect of parenchyma amyloid but similar to that of other vascular risk factors. This is consistent with the notion that CAA is often considered one sub-type of small vessel diseases. Fifth, although TRUST is relatively fast (1.2 min scan time), motion during the scan can still degrade the data quality and caused six subjects to be excluded in our study. Finally, our study only provides a global OEF measure and lacks spatial information. Since certain types of VCI, such as post-stroke VCI, may affect focal brain regions, a localized measure of OEF may be needed to provide sufficient diagnostic sensitivity under those conditions. Therefore, techniques that can measure regional OEF are desirable and are being developed in the field (37–40).

Conclusion

We showed that OEF is differentially affected by Alzheimer’s and vascular pathology in elderly individuals with cognitive impairment. This functional measure of the brain may be a complementary marker to amyloid and tau imaging in clinical diagnosis of dementia and may help enrich trial cohorts for targeting Alzheimer’s disease and/or VCI interventions.

Supplementary Material

Grant Support:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health: NIH R01 MH084021, NIH R01 NS106711, NIH R01 NS106702, NIH R01 AG047972, NIH R21 NS095342, NIH R21 NS085634, NIH P41 EB015909, NIH S10 OD021648, and NIH UH2 NS100588.

List of Abbreviations

- Aβ40

β-amyloid-40

- Aβ42

β-amyloid-42

- BBB

blood-brain-barrier

- BMI

body mass index

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- EtCO2

end-tidal carbon dioxide

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated-inversion-recovery

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OEF

oxygen extraction fraction

- PET

positron emission tomography

- p-tau

phosphorylated tau

- TRUST

T2-relaxation-under-spin-tagging

- VCI

vascular cognitive impairment

- VRS

vascular risk score

- WMH

white matter hyperintensities

References

- 1.Stevens T, Livingston G, Kitchen G, Manela M, Walker Z, Katona C. Islington study of dementia subtypes in the community. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg GA, Wallin A, Wardlaw JM, et al. Consensus statement for diagnosis of subcortical small vessel disease. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2016;36:6–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roman GC, Erkinjuntti T, Wallin A, Pantoni L, Chui HC. Subcortical ischaemic vascular dementia. Lancet Neurol 2002;1:426–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buxton RB, Uludag K, Dubowitz DJ, Liu TT. Modeling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage 2004;23:S220–S233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubb RL Jr., Derdeyn CP, Fritsch SM, et al. Importance of hemodynamic factors in the prognosis of symptomatic carotid occlusion. JAMA 1998;280:1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edison P, Archer HA, Hinz R, et al. Amyloid, hypometabolism, and cognition in Alzheimer disease: an [11C]PIB and [18F]FDG PET study. Neurology 2007;68:501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas BP, Sheng M, Tseng BY, et al. Reduced global brain metabolism but maintained vascular function in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017;37:1508–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frackowiak RS, Pozzilli C, Legg NJ, et al. Regional cerebral oxygen supply and utilization in dementia. A clinical and physiological study with oxygen-15 and positron tomography. Brain 1981;104:753–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu H, Ge Y. Quantitative evaluation of oxygenation in venous vessels using T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med 2008;60:357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu H, Xu F, Grgac K, Liu P, Qin Q, van Zijl P. Calibration and validation of TRUST MRI for the estimation of cerebral blood oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 2012;67:42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang D, Deng S, Franklin C, et al. Validation of T2-based Oxygen Extraction Fraction Measurement with 15O Positron Emission Tomography. Magn Reson Med 2020; Under Revision. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang D, Liu P, Li Y, Mao D, Xu C, Lu H. Cross-vendor harmonization of T2 -relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI for the assessment of cerebral venous oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 2018;80:1125–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P, Dimitrov I, Andrews T, et al. Multisite evaluations of a T2 -relaxation-under-spin-tagging (TRUST) MRI technique to measure brain oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 2016;75:680–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia 2011;7:270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale - Revised. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandt J, Benedict R. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised, professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reitan RM. The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol 1955;19:393–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wechsler D WAIS-R Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised Manual. New York, NY: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanova I, Salmon DP, Gollan TH. The multilingual naming test in Alzheimer’s disease: clues to the origin of naming impairments. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2013;19:272–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benton A, Hamsher K. Multilingual Aphasia Examination manual. Iowa City: University of Iowa; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewczuk P, Esselmann H, Otto M, et al. Neurochemical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia by CSF Aβ42, Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio and total tau. Neurobiology of aging 2004;25:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottesman RF, Schneider AL, Zhou Y, et al. Association Between Midlife Vascular Risk Factors and Estimated Brain Amyloid Deposition. JAMA 2017;317:1443–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu H, Xu F, Rodrigue KM, et al. Alterations in cerebral metabolic rate and blood supply across the adult lifespan. Cereb Cortex 2011;21:1426–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang D, Lin Z, Liu P, et al. Normal variations in brain oxygen extraction fraction are partly attributed to differences in end-tidal CO2. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019:271678X19867154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. Am J Roentgenol 1987;149:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aanerud J, Borghammer P, Chakravarty MM, et al. Brain energy metabolism and blood flow differences in healthy aging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012;32:1177–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1509–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tijms BM, Wink AM, de Haan W, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: connecting findings from graph theoretical studies of brain networks. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:2023–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musiek ES, Chen Y, Korczykowski M, et al. Direct comparison of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mak HK, Chan Q, Zhang Z, et al. Quantitative assessment of cerebral hemodynamic parameters by QUASAR arterial spin labeling in Alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal Elderly adults at 3-tesla. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;31:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao H, Sadoshima S, Kuwabara Y, Ichiya Y, Fujishima M. Cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism in patients with vascular dementia of the Binswanger type. Stroke 1990;21:1694–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagata K, Buchan RJ, Yokoyama E, et al. Misery perfusion with preserved vascular reactivity in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997;826:272–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Z, Sur S, Soldan A, et al. Brain Oxygen Extraction by Using MRI in Older Individuals: Relationship to Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Amyloid Burden. Radiology 2019;292:140–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med 2019;25:270–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, et al. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron 2010;68:409–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gauthier CJ, Hoge RD. Magnetic resonance imaging of resting OEF and CMRO(2) using a generalized calibration model for hypercapnia and hyperoxia. Neuroimage 2012;60:1212–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu B, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Prince M, Wang Y. Flow compensated quantitative susceptibility mapping for venous oxygenation imaging. Magn Reson Med 2014;72:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bulte DP, Kelly M, Germuska M, et al. Quantitative measurement of cerebral physiology using respiratory-calibrated MRI. Neuroimage 2012;60:582–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Germuska M, Wise RG. Calibrated fMRI for mapping absolute CMRO2: Practicalities and prospects. Neuroimage 2019;187:145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.