Abstract

The genes encoding NAD+-dependent alanine dehydrogenases (AlaDHs) (EC 1.4.1.1) from the Antarctic bacterial organisms Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 (SheAlaDH) and Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 (CarAlaDH) were cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli. Of all of the AlaDHs that have been sequenced, SheAlaDH exhibited the highest level of sequence similarity to the AlaDH from the gram-negative bacterium Vibrio proteolyticus (VprAlaDH). CarAlaDH was most similar to AlaDHs from mesophilic and thermophilic Bacillus strains. SheAlaDH and CarAlaDH had features typical of cold-adapted enzymes; both the optimal temperature for catalytic activity and the temperature limit for retaining thermostability were lower than the values obtained for the mesophilic counterparts. The kcat/Km value for the SheAlaDH reaction was about three times higher than the kcat/Km value for VprAlaDH, but it was much lower than the kcat/Km value for the AlaDH from Bacillus subtilis. Homology-based structural models of various AlaDHs, including the two psychrotrophic AlaDHs, were constructed. The thermal instability of SheAlaDH and CarAlaDH may result from relatively low numbers of salt bridges in these proteins.

The enzymes of psychrophilic microorganisms adapted to permanently low temperatures have attracted much less attention than the enzymes of thermophiles. However, cold-adapted enzymes produced by psychrophiles could be useful for various industrial applications and also for studying the structure-stability relationship in proteins (14, 23, 30). However, only a limited number of cold-adapted enzymes have been characterized.

Cold-adapted enzymes with high levels of catalytic activity at low temperatures are believed to have acquired, through evolution, increased flexibility in their protein structures in order to increase their catalytic abilities. Crystal structures (1, 3, 31) and three-dimensional models (2, 11, 28, 35) of cold-adapted enzymes have shown that these enzymes contain a reduced number of protein stabilization factors, such as salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and aromatic-aromatic contacts, and reduced proline and arginine contents compared with their mesophilic counterparts. However, little attention has been paid to the taxonomic similarities of source organisms as a crucial factor for comparing psychrophilic and mesophilic enzymes; reasonable comparisons can be made only by studying a set of enzymes from organisms belonging to similar taxonomic groups.

NAD+-dependent alanine dehydrogenase (AlaDH) (EC1.4.1.1), which catalyzes reversible deamination of l-alanine to pyruvate, can be used for enantioselective production of optically active amino acids (13, 15). In particular, various d-amino acids are produced efficiently from the corresponding α-keto acids by a multienzyme system that includes AlaDH, alanine racemase (EC 5.1.1.1), d-amino acid aminotransferase (EC 2.6.1.21), and formate dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.1.2) (15). However, some of the substrate α-keto acids (e.g., oxaloacetate and β-chloropyruvate) are unstable and are degraded during prolonged incubation at moderate temperatures, such as 37°C. Cold-adapted enzymes that exhibit high levels of activity at low temperatures should be useful for converting such unstable α-keto acids, because they are relatively stable at low temperatures. Thus, we have been looking for cold-active enzymes in cold-adapted microorganisms in order to use them in the production system described above. We have previously obtained cold-active alanine racemases from cold-adapted bacterial strains (29, 38). Here we describe characteristics of cold-active AlaDHs of cold-adapted microorganisms.

AlaDH genes were cloned from mesophilic and thermophilic gram-positive bacteria (4, 19) and a gram-negative bacterium, Vibrio proteolyticus (17). Recently, the X-ray structure of the AlaDH from the cyanobacterium Phormidium lapideum (PlaAlaDH) was determined at high resolution (6). We cloned AlaDH genes from two psychrotrophic bacterial strains belonging to different divisions in the bacterial domain, Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 and Carnobacterium sp. strain St2. We constructed three-dimensional structural models of the cold-active AlaDHs of these organisms in order to compare them with their mesophilic and thermophilic counterparts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes, chemicals, bacterial strains, and plasmids.

AlaDH from Bacillus subtilis (BsuAlaDH) was purchased from Sigma, and AlaDH from Bacillus stearothermophilus (BstAlaDH) was provided by Hitoshi Kondo of Unitika Ltd., Osaka, Japan. AlaDH from V. proteolyticus (VprAlaDH) was purified from recombinant strain E. coli TG1 containing plasmid pVprAlaDH (17). Restriction enzymes and other DNA-modifying enzymes were purchased from Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan, or Toyobo, Osaka, Japan. All other chemicals were obtained from Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan, or Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan. The oligonucleotides were purchased from Biologica, Nagoya, Japan. The gram-positive psychrotrophic organism Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 was isolated from Antarctic seawater and was cultivated in 1 liter of a medium (pH 7.5) containing (per liter) 1.2 g of yeast extract, 2.3 g of Polypeptone, 0.3 g of sodium citrate, 0.3 g of glutamic acid, 50 mg of sodium nitrate, 5 mg of ferrous sulfate, and synthetic sea salts (Jamarin S; Jamarin Laboratory). The gram-negative psychrotrophic organism Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 was cultured as described previously (18).

Escherichia coli has no NAD+-dependent AlaDH activity, and we used E. coli TG1 [F′ traD36 proAB lacIq ΔlacZ M15 Δ(lac-pro) thi hsdR ara], JM109 [recA 1 F′ traD36 proAB e14(McrA) lacIq ΔlacZ M15 Δ(lac-pro) girA96 thi hsdR17 relA1 supE44 ara], or C600 [F− thr-1 leu56 e14(McrA) thi supE44 lacY1 rfbD1 fhuA21] for expression of AlaDH genes.

Fatty acid composition.

The fatty acid composition of Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 was determined with a Shimadzu model GC-14A gas-liquid chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector and a type HR101 capillary column as described previously (18).

DNA manipulation and sequence analysis.

DNA was sequenced with an Applied Biosystems model 377B automated DNA sequencer and a dye-labeled terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The PCR was performed with a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) by using 0.05 ml of a mixture containing deoxynucleoside triphosphates at a total concentration of 0.2 mM, 100 pmol of each primer, 10 ng of template DNA, an appropriate reaction buffer, and 2.5 U of exTaq or LATaq DNA polymerase (Takara). The 16S rRNA genes (rDNA) were amplified by PCR performed with the chromosomal DNA of Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 as the template by using the method of Weisburg et al. (36) and were sequenced. The sequences were compared with sequences retrieved from the Ribosomal Database Project (22), as well as from the GenBank and EMBL databases; they were classified with the GenCANS-RDP system (36a, 37). Sequences were aligned and phylogenetic trees were constructed with the MEGALIGN program by using the CLUSTAL method (10).

Gene cloning and plasmid construction.

Fragments of the chromosomal DNA of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 and Carnobacterium sp. strain St2, which were obtained by partial digestion with Sau3AI, were ligated into the BamHI site of pUC118. E. coli TG1 was used as the host for library construction. Positive clones carrying AlaDH genes were selected from gene libraries by colony hybridization with DNA probes labeled with digoxigenin. DNA probes specific for AlaDH genes were obtained by performing PCR with the following primers designed for two consensus sequences in AlaDHs: forward primer 5′-GAA(orG)ATT(or C or A)AAA(orG)AAT(or C)AAT(or C)GAA(or G)TA and reverse primer 5′-CCIGCIACT(or C)TCIG(or C)A(or T)CATIGG. The following program was used: 45 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 33 to 38°C for 2 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. All AlaDH genes that contained no flanking regions were prepared further by performing PCR with cloned AlaDH genes for production of overproducing plasmids. The following primers were used: for Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 AlaDH (SheAlaDH), 5′-CGAGGATCCATATATGATTATTGGTGTTCCAACAG (forward) and 5′-TACGAATTCAAGCAAGTAGGCTTTTTGG (reverse); and for Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 AlaDH (CarAlaDH), 5′-GAGGGATCCTTATATGAAAATCGGTATACCTAAAG (forward) and 5′-TTTGAATTCTATTTATTGAAACAAGTACTTGC (reverse). The genes obtained were digested with BamHI and EcoRI and then ligated as described previously (13) into the BamHI-EcoRI site of plasmid pFDHAlaDH downstream of the lac and tac promoters, which were tandemly connected. The resulting plasmids encoding the AlaDH genes of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 and Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 were designated pSheAlaDH2 and pCarAlaDH2, respectively.

Assays.

AlaDH activity was assayed by monitoring the reduction of NAD+ at 25°C in a 1-ml mixture containing 200 μmol of glycine-KCl-KOH buffer (pH 10.0), 70 μmol of l-alanine, 1.0 μmol of NAD+, and AlaDH. Protein was assayed with Coomassie blue dye by using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyzed the formation of 1 μmol of NADH per min. Kinetic constants were determined from duplicate or triplicate measurements of the initial rates by varying the concentrations of one substrate when the concentration of the second substrate was kept constant. Data fitting was conducted with KaleidaGraph software (Adelbeck Software). Protein molecular masses were estimated by gel filtration performed with a Superdex-200 fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer supplemented with 200 mM NaCl (pH 7.2). The molecular mass markers used were bovine liver catalase (240 to 250 kDa), yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), bovine serum albumin (68 kDa), bovine erythrocyte carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), and horse heart cytochrome c (12 kDa).

Protein purification.

SheAlaDH was purified from recombinant E. coli TG1 cells carrying pSheAlaDH2. All procedures were performed in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). The cells (2.7 g [wet weight]) were suspended in 10 ml of buffer and subjected to sonication. After centrifugation, ammonium sulfate was added to the supernatant solution to a final concentration of 2 M. After centrifugation, the supernatant solution was applied to a Phenyl-Superose FPLC column (Pharmacia). The enzyme was eluted with a 2 to 0 M ammonium sulfate gradient. The active fractions were pooled and concentrated with a Centricon-50 concentrator (Amicon); they were then applied to an FPLC Superdex 200 column (Pharmacia). In the final step, the enzyme solution was applied to a MonoQ FPLC column (Pharmacia) and was eluted with a 0 to 0.4 M NaCl gradient.

Molecular modeling and structural analysis.

The structures of AlaDHs were predicted by homology modeling. This was done on the basis of the PlaAlaDH structure, which was used as a reference, by using the program MODELLER, version 4 (32). There is intense interaction between the A and D subunits of homohexameric PlaAlaDH (6); the coordinates of both subunits were used. Five models were generated for each AlaDH by using complete optimization cycles, conjugate gradients, and simulated annealing. The quality of each structure was examined with PROCHECK (21), and the models with the best stereochemical parameters were selected for generation of hexameric structures with QUANTA 4.0 (Molecular Simulations, Burlington, Mass.). Corrections were made with QUANTA rotameric libraries to avoid close contact of the side chains at other intersubunit interfaces. The quality of the models was evaluated further with the Protein Health and 3D profile (8) modules of QUANTA. All other estimates of structural parameters were obtained with the software packages Quanta 4.0 and Insight II (Molecular Simulations). Calculations were performed with a Silicon Graphics Indigo 2 workstation.

A salt bridge was defined as an ion pair with a distance of 2.5 to 4 Å between charged nonhydrogen atoms (7). The distance cutoff was applied to carboxylate oxygen atoms of Glu and Asp; NE, NH1, and NH2 of Arg; NZ of Lys; and ND1 and ND2 of His. In the case of surface residues, we used essentially the same procedure that Szilagyi and Zavodszky (34) used. The rotamer conformations of charged residue pairs were obtained from QUANTA rotameric libraries and were checked for the possibility of salt bridge formation. Aromatic-aromatic interactions were defined as pairs of aromatic residues in which the distance between phenyl ring centroids was less than 7 Å (9). The hydrogen bonds were calculated by using a cutoff distance between the hydrogen donor and acceptor atoms of 3.3 Å. The cutoff angle formed by the acceptor, hydrogen, and donor atoms was set at 90°.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the nucleotide sequences which we determined are as follows: 16S rDNA of Carnobacterium sp. strain St2, AF061558; CarAlaDH, AF070714; SheAlaDH, AF070715; and VprAlaDH, AF070716.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Screening of cold-adapted bacteria carrying the AlaDH gene.

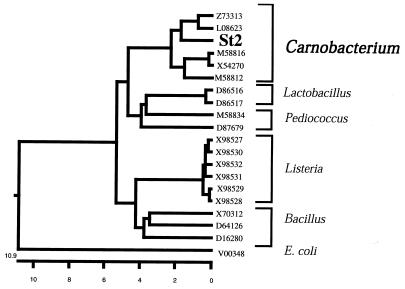

We searched for cold-adapted bacterial strains carrying AlaDH genes in our stock cultures by using PCR and found that gram-positive strain St2 is a carrier of the gene. This strain grows well at 4°C, and its optimum growth temperature is around 20°C; it grows little at temperatures higher than 30°C. According to Morita’s definition (26), strain St2 is classified as a psychrotroph. We found that docosahexaenoic acid accounted for 6% of the total fatty acids in this strain and that this organism contained polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid, which is characteristic of cold-adapted microorganisms (30). Strain St2 seemed to be a member of the low-G+C-content gram-positive bacterial group on the basis of its 16S rDNA sequence (Fig. 1). It was most similar to an Antarctic organism, Carnobacterium alterfunditum (12). Therefore, we referred to this strain as Carnobacterium sp. strain St2. Shewanella sp. strain Ac10, a gram-negative Antarctic psychrotroph, is another strain in our stock cultures which has an AlaDH gene. This strain grows well at 4°C, and optimum growth occurs at temperatures around 20°C; little growth occurs at temperatures above 30°C. The taxonomic properties and fatty acid composition of this strain have been reported previously (18).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship between the 16S rDNA sequence of Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 and the 16S rDNA sequence of other Carnobacterium strains and selected Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Listeria, and Bacillus strains. The balanced cladogram was constructed from a matrix of pairwise genetic distances generated by the CLUSTAL method by using the MEGALIGN program (10). The scale indicates percentages of sequence divergence. GenBank accession numbers for the 16S rDNA sequences of various bacteria are shown.

Cloning and expression of AlaDH genes.

We obtained the AlaDH genes from Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 and Carnobacterium sp. strain St2, as described above. The level of expression of SheAlaDH in the clone cells (E. coli TG1 carrying pSheAlaDH2) was around 10% of the total soluble protein, as determined on the basis of the specific activity of AlaDH in the cell extract (about 4 U/mg of protein). The specific activity was not influenced by cultivation temperatures between 20 and 37°C. However, this was not the case with expression of CarAlaDH. No AlaDH activity was found in the extract of E. coli TG1 cells harboring pCarAlaDH2 when the cells were cultured at 37°C, although a low but definite level of activity (0.03 to 0.07 U/mg of protein) was detected in the extract when the culture was grown at temperatures lower than 30°C. The expression system consisting of E. coli TG1 as the host strain and pFDHAlaDH (13), from which pCarAlaDH2 was derived, as the host vector exhibited the highest level of AlaDH activity among all of the combinations examined, including systems in which pUC118, pKK233-2, or pFDHAlaDH was the vector and E. coli JM109, C600, or TG1 was the host strain. None of these combinations exhibited detectable AlaDH activity when they were cultured at 37°C.

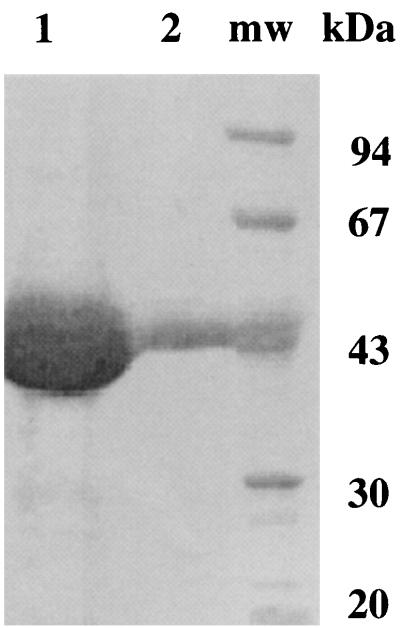

SheAlaDH was purified with a satisfactory yield (Table 1) to the level of a single major protein band on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (Fig. 2). On the other hand, CarAlaDH was inactivated extensively during purification and could not be purified from either E. coli TG1 harboring pCarAlaDH2 or Carnobacterium sp. strain St2; CarAlaDH is extremely unstable and is easily lysed.

TABLE 1.

Purification of SheAlaDH from E. coli TG1 carrying pSheAlaDH2a

| Prepn | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 96 | 340 | 3.5 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate fractionation | 54 | 260 | 4.8 | 76 |

| Phenyl Superose hydrophobic chromatography (FPLC) | 5.9 | 140 | 24 | 41 |

| Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography (FPLC) | 3.6 | 120 | 33 | 35 |

| MonoQ anion-exchange chromatography (FPLC) | 2.5 | 100 | 40 | 29 |

Data were obtained with an extract obtained from 2.7 g (wet weight) of cells.

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of purified SheAlaDH fractions N1 (lane 1) and N2 (lane 2) after the last stage of enzyme purification on a MonoQ ion-exchange column. Lane mw contained molecular weight markers.

Sequence similarity and phylogenetic analysis.

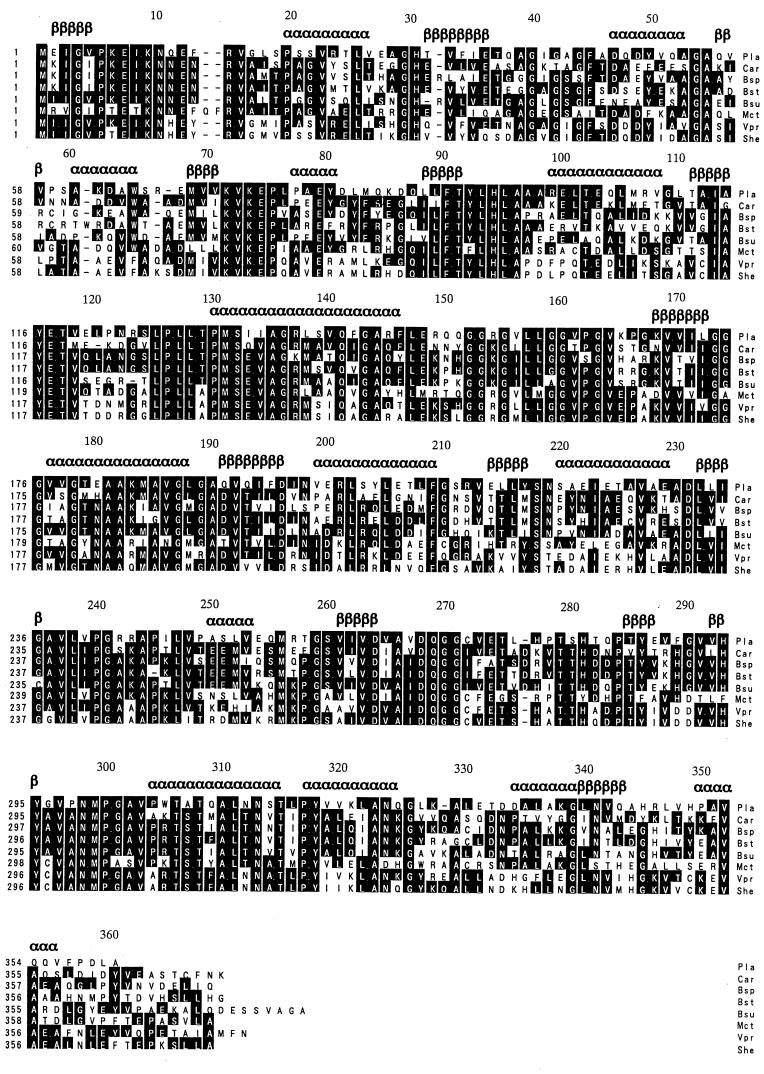

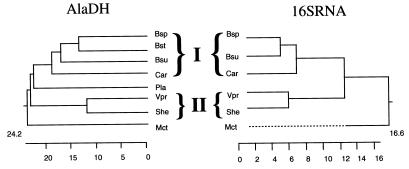

The amino acid sequences of CarAlaDH and SheAlaDH were compared with the sequences of AlaDHs from other bacterial sources (Fig. 3). CarAlaDH exhibited the highest overall levels of identity (58.5 to 62.8%) with the enzymes from members of the same group of bacteria (the low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria), such as B. stearothermophilus. Furthermore, SheAlaDH was most similar (level of identity, 76.5%) to VprAlaDH; V. proteolyticus is a mesophilic gram-negative bacterium belonging to the same group in the γ-subdivision of the class Proteobacteria as Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. However, the level of sequence identity between SheAlaDH and CarAlaDH was low (47.4%). The phylogenetic relationships among AlaDHs were compared with the phylogenetic relationships among 16S rDNAs from the same organisms (Fig. 4). The branching patterns in the two phylogenetic trees were similar, indicating that the relationships among the AlaDH genes were not discontinuous due to, for, example horizontal gene transfer. Each AlaDH probably evolved separately from other AlaDHs in order to fulfill the individual metabolic requirements of each strain. Thus, it is reasonable to classify AlaDHs in two clusters, AlaDHs from low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria and AlaDHs from members of the γ-subdivision of the Proteobacteria (gram-negative phylum). Structural factors that affect adaptation of AlaDHs to different temperatures may be determined by comparing AlaDHs from members of the same group.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of AlaDHs from Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 (Car), B. subtilis (Bsu), Bacillus sphaericus (Bsp), V. proteolyticus (Vpr), Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 (She), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mct), B. stearothermophilus (Bst), and P. lapideum (Pla). Secondary-structure elements of PlaAlaDH are indicated by α and β. The numbers are residue numbers in PlaAlaDH.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of phylogenetic trees for AlaDHs and 16S rDNAs from various bacterial strains. I and II indicate low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria and members of the γ-subdivision of the Proteobacteria, respectively. AlaDHs from P. lapideum (Pla) and B. stearothermophilus (Bst) were also included in the analysis, although the 16S rDNA sequences of these organisms could not be obtained. For other abbreviations see the legend to Fig. 3.

Characterization of psychrotrophic AlaDHs.

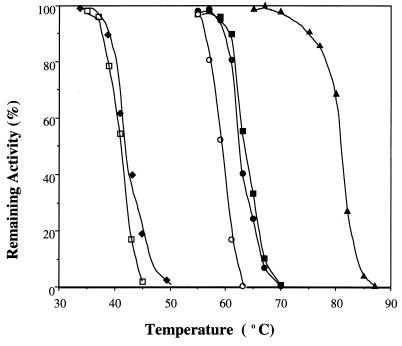

The optimum temperatures for catalytic activities of AlaDHs (Table 2) are in the same range as the half-inactivation temperatures. SheAlaDH was more stable than CarAlaDH but was less stable than all of the AlaDHs from mesophilic and thermophilic strains (Fig. 5). Thus, both of the AlaDHs from psychrotrophs have features that are characteristic of cold-adapted enzymes. The thermal stability of CarAlaDH did not change whether it was produced by recombinant E. coli TG1/pCarAlaDH2 cells or original Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 cells (Fig. 5). The instability of CarAlaDH is probably an inherent characteristic of the enzyme.

TABLE 2.

Properties of AlaDHs

| Parameter | Source of AlaDH gene

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Subdivision of the Proteobacteria

|

Low-G+C-content gram-positive bacteria

|

||||

| V. proteolyticus | Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 | B. stearothermophilus | B. subtilis | Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 | |

| Optimum growth temp (°C) | 37 | 20 | 57 | 37 | 20 |

| Thermostability (°C)a | 63 | 59 | 81 | 64b | 41c |

| Maximum activity temp (°C) | 53–57 | 47–50 | 75–80 | 60–64b | 35–38c |

| Km for l-alanine (mM) | 30 | 7.6 | NDd | 1.73b | 3.8c |

| Km for NAD+ (mM) | 0.21 | 0.24 | ND | 0.18b | 0.2c |

| kcat (s−1) | 36 | 27 | ND | 47–140b | ND |

| kcat/Km for l-alanine (mM−1 s−1) | 1.2 | 3.5 | ND | 27–81b | ND |

| Arg/(Arg + Lys) ratio | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.5 | 0.34 | 0.19 |

| Proline content (%) | 4.5 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Glycine content (%) | 8.8 | 9.4 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 10.1 |

| No. of salt bridgese | 117 | 87 | 132 | 99 | 60 |

| No. of aromatic interactionse | 36 | 30 | 54 | 42 | 48 |

| No. of hydrogen bondse | 1,892 | 1,986 | 1,936 | 1,947 | 1,962 |

| Hydrophobic interactionsf | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| No. of loop insertions/no. of deletionsg | 2/0 | 2/0 | 3/1 | 2/1 | 2/1 |

Temperature at which the enzyme loses 50% of its original level of activity after 30 min of incubation.

Data obtained from reference 36.

The values were estimated from the results obtained with a crude enzyme preparation.

ND, Not determined.

Total number in hexamer.

Ratio of buried apolar surface area to polar surface area.

Compared with PlaAlaDH.

FIG. 5.

Thermal stabilities of AlaDHs from the psychrotropic organisms Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 (recombinant [□] and wild type [⧫]) and Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 (○), the mesophilic organisms V. proteolyticus (●) and B. subtilis (■), and the thermophilic organism B. stearothermophilus (▴). The activities of AlaDHs remaining after incubation for 30 min at different temperatures in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) are shown.

The measured temperature indices (temperature-activity and temperature-stability relationships) of SheAlaDH and VprAlaDH differ only by several degrees centigrade. On the other hand, CarAlaDH is significantly different from BsuAlaDH and BstAlaDH. Therefore, the AlaDHs from gram-positive strains should be good tools for studying structure-stability relationships. However, we used a crude extract of E. coli TG1/pCarAlaDH2 cells to characterize CarAlaDH.

The kinetic properties of the psychrotrophic enzymes are shown in Table 2. Although the kcat value of SheAlaDH is slightly lower than the kcat value of VprAlaDH, the kcat/Km value of SheAlaDH is nearly three times as high as the kcat/Km value of VprAlaDH. However, the kcat/Km value of BsuAlaDH is at least nine times higher than the kcat/Km value of SheAlaDH. AlaDH is known to be essential for normal sporulation of B. subtilis (33). It may be interesting to assume that AlaDHs from spore-forming bacteria are more advanced evolutionarily and more active than AlaDHs from nonsporulating bacteria. AlaDHs from gram-negative (non-spore-forming) bacteria may have been subjected to lower selective pressures during evolution than AlaDHs from gram-positive bacteria.

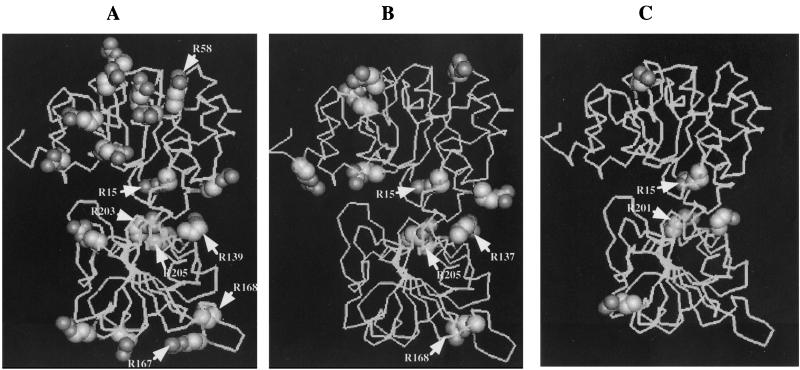

Structural characteristics of psychrotrophic AlaDHs.

Arginine residues form more stable bonds and provide more favorable interactions at protein-protein and protein-solvent interfaces than lysine residues. Thus, the arginine residue content is considered an important factor for protein stability (5, 25, 27). We found that there was a clear relationship between the arginine residue content and thermostability in the three AlaDHs from gram-positive bacteria, CarAlaDH, BsuAlaDH, and BstAlaDH (Fig. 6). We observed a similar relationship between the thermostability of the three AlaDHs and the molar ratio of arginine residues relative to total basic residues (Arg plus Lys) (Table 2). Therefore, the thermal instability of CarAlaDH may be explained by its low arginine residue content and its low ratio of Arg to Arg plus Lys. SheAlaDH is less thermostable than VprAlaDH, but the difference is slight (Table 2). Thus, the difference between SheAlaDH and VprAlaDH is probably determined by factors other than those related to arginine residues (Table 2). Proline and glycine residues are thought to modulate the entropy of protein unfolding by affecting backbone flexibility (24). However, the thermal stability of AlaDHs cannot be explained by the contents of these amino acids (Table 2). Furthermore, we found that the psychrotrophic and mesophilic AlaDHs did not differ in other indices calculated by using amino acid compositions, such as hydropathicity (20) and aliphatic index (16) (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Locations of arginine residues in the three-dimensional structural models of AlaDHs from the thermophilic organism B. stearothermophilus (A), the mesophilic organism B. subtilis (B), and the psychrotrophic organism Carnobacterium sp. strain St2 (C). The arginine residues are shown as space-filling models, and the residues that form salt bridges are indicated by arrows. The lines indicate the Cα traces of the protein monomers.

Homology modeling of psychrotrophic AlaDHs.

PlaAlaDH is a homohexamer (6), and other AlaDHs, such as VprAlaDH (17) and BstAlaDH (19), have been found to have the same subunit structure. The molecular mass of SheAlaDH was estimated to be about 240,000 Da by gel filtration. This result, together with the SDS-PAGE results (Fig. 2), indicates that SheAlaDH is also a homohexamer. Although the molecular mass of CarAlaDH could not be determined due to the instability of this enzyme, we assumed that CarAlaDH is also a homohexamer. Using the X-ray structure of PlaAlaDH as a reference, we constructed structural models for two psychrotrophic AlaDHs, two mesophilic AlaDHs, and one thermophilic AlaDH by using homology modeling. Various factors that may determine the thermal stabilities of the psychrotrophic AlaDHs were estimated based on the structures.

We found that the total numbers of salt bridges declined in the order thermophilic AlaDH-mesophilic AlaDHs-psychrotrophic AlaDHs when we compared AlaDHs from members of the same bacterial subgroups (SheAlaDH and VprAlaDH; and BstAlaDH, BsuAlaDH, and CarAlaDH) (Table 2). The structural model for CarAlaDH indicates that it has two and five fewer arginine residues forming salt bridges per subunit than BsuAlaDH and BstAlaDH, respectively (Fig. 6). The thermal instability of CarAlaDH may be explained by the lower total number of salt bridges, in particular salt bridges formed by arginine residues, in the enzyme. However, other structural features often found in proteins isolated from cold-adapted organisms, such as lower numbers of extended surface loops (14, 34) and aromatic-aromatic interactions (14, 28), were not evident in the structural models of the psychrotrophic AlaDHs. Thus, the cold-adapted AlaDHs are unique in that their thermal instability depends primarily on lower salt bridge contents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Rice and Patrick Baker of Sheffield University, Sheffield, United Kingdom, for helpful discussions and for kindly providing the coordinates of the PlaAlaDH structure. We are also grateful to Charles Gerday, University de Liege, Liege, Belgium, Minoru Kanehisa, Junji Fukumoto, and other members of Supercomputer Laboratory, Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University, for their encouragement and valuable discussions.

This work was supported in part by a research grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Research for the Future).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aghajari N, Feller G, Gerday C, Haser R. Structures of the psychrophilic Alteromonas haloplanctis α-amylase give insights into cold adaptation at a molecular level. Structure. 1998;6:1503–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aittaleb M, Hubner R, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Gerday C. Cold adaptation parameters derived from cDNA sequencing and molecular modeling of elastase from Antarctic fish Notothenia neglecta. Protein Eng. 1997;10:475–477. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.5.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez M, Zeelen J P, Mainfroid V, Rentier-Delrue F, Martia J A, Wyns L, Wierenga R K, Maes D. Triose-phosphate isomerase (TIM) of the psychrophilic bacterium Vibrio marinus. Kinetic and structural properties. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2199–2206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen A B, Andersen P, Ljungqvist L. Structure and function of a 40,000-molecular-weight protein antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2317–2323. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2317-2323.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argos P, Rossman M G, Grau U M, Zuber H, Frank G, Tratschin J D. Thermal stability and protein structure. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5698–5703. doi: 10.1021/bi00592a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker P J, Sawa Y, Shibata H, Sedelnikova S E, Rice D W. Analysis of the structure and substrate binding of Phormidium lapideum alanine dehydrogenase. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:561–567. doi: 10.1038/817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow D J, Thornton J M. Ion-pairs in proteins. J Mol Biol. 1983;168:867–885. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowie J U, Luthy R, Eisenberg D. A method to identify protein sequences that fold into a known three-dimensional structure. Science. 1991;253:164–170. doi: 10.1126/science.1853201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burley S K, Petsko G A. Aromatic-aromatic interaction: a mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science. 1995;229:23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.3892686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clewley J P, Arnold C. MEGALIGN. The multiple alignment module of LASERGENE. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;70:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feller G, Zekhnini Z, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Gerday C. Enzymes from cold-adapted microorganisms. The class C β-lactamase from the Antarctic psychrophile Psychrobacter immobilis A5. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:186–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzmann P D, Hopfl P, Weiss N, Tindall B J. Psychrotrophic, lactic acid-producing bacteria from anoxic waters in Ace Lake, Antarctica; Carnobacterium funditum sp. nov. and Carnobacterium alterfunditum sp. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:255–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00262994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galkin A, Kulakova L, Yoshimura T, Soda K, Esaki N. Synthesis of optically-active amino acids from the corresponding α-keto acids with Escherichia coli cells expressing heterologous genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4651–4656. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4651-4656.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerday C, Aittaleb M, Arpigny J L, Baise E, Chessa J P, Garsoux G, Petrescu I, Feller G. Psychrophilic enzymes: a thermodynamic challenge. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1342:119–131. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hummel W, Kula M-R. Dehydrogenase for the synthesis of chiral compounds. Eur J Biochem. 1989;184:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikai A. Thermostability and aliphatic index of globular proteins. J Biochem. 1980;88:1895–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato S, Ohshima T, Ishihara K, Galkin A, Yoshimura T, Esaki N, Soda K. Purification and properties of alanine dehydrogenase from Vibrio proteolyticus. Nihon Nougeikagaku Kaishi. 1997;71:293. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulakova L, Galkin A, Kurihara T, Yoshimura T, Esaki N. Cold-active serine alkaline protease from the psychrotrophic bacterium Shewanella strain Ac10: gene cloning and enzyme purification and characterization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:611–617. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.611-617.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroda S, Tanizawa K, Sakamoto Y, Tanaka H, Soda K. Alanine dehydrogenase from two Bacillus species with distinct thermostabilities: molecular cloning, DNA and protein sequence determination, and structural comparison with other NAD(P)-dependent dehydrogenases. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1009–1015. doi: 10.1021/bi00456a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thornton J M. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J, Woese C R. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–111. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marshall C J. Cold-adapted enzymes. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:359–364. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews B W, Nicholson H, Becktel W J. Enhanced protein thermostability from site-directed mutations that decrease the entropy of unfolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6663–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menendez-Arias L, Argos P. Engineering protein thermal stability. Sequence statistics point to residue substitutions in α-helices. J Mol Biol. 1989;206:397–406. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morita R Y. Psychrophilic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1975;39:144–167. doi: 10.1128/br.39.2.144-167.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrabet N T, Van den Broeck A, Van den Brande I, Stanssens P, Laroche Y, Lambeir A M, Matthijssens G, Jenkins J, Chiadmi M, Van Tilbeurgh H. Arginine residues as stabilizing elements in proteins. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2239–2253. doi: 10.1021/bi00123a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narinx E, Baise E, Gerday C. Subtilisin from psychrophilic Antarctic bacteria: characterization and site-directed mutagenesis of residues possibly involved in the adaptation to cold. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1271–1279. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.11.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okubo Y, Yokoigawa K, Esaki N, Soda K, Kawai H. Characterization of psychrophilic alanine racemase from Bacillus psychrosaccharolyticus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:333–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell N J. Physiology and molecular biology of psychrophilic micro-organisms. In: Herbert R A, Sharp R J, editors. Molecular biology and biotechnology of extremophiles. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall, Inc.; 1992. pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell R J, Gerike U, Danson M J, Hough D W, Taylor G L. Structural adaptations of the cold-active citrate synthase from an Antarctic bacterium. Structure. 1998;6:351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sali A, Blundell T L. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siranosian K J, Ireton K, Grossman A D. Alanine dehydrogenase (ald) is required for normal sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6789–6796. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6789-6796.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szilagyi A, Zavodszky P. Structural basis for the extreme thermostability of d-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase from Thermotoga maritima: analysis based on homology modeling. Protein Eng. 1995;8:779–789. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.8.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallon G, Lovett S T, Magyar C, Svingor A, Szilagyi A, Zavodszky P, Ringe D, Petsko G A. Sequence and homology model of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase from the psychrotrophic bacterium Vibrio sp. 15 suggest reasons for thermal instability. Protein Eng. 1997;10:665–672. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Wu, C. Protein Information Resource. http://pir.georgetown.edu/gfserver/genefind.html. [26 July 1999, last date accessed.]

- 37.Wu C, Shivakumar S. Back-propagation and counter-propagation neural networks for phylogenetic classification of ribosomal RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4291–4299. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokoigawa K, Kawai H, Endo K, Lim Y H, Esaki N, Soda K. Thermolabile alanine racemase from a psychrotroph, Pseudomonas fluorescens; purification and properties. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:93–97. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida A, Freese E. Enzymic properties of alanine dehydrogenase of Bacillus subtilis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;96:248–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]