Abstract

The Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, has resulted in unprecedented morbidity and mortality worldwide. While COVID-19 typically presents as viral pneumonia, cardiovascular manifestations such as acute coronary syndromes, arterial and venous thrombosis, acutely decompensated heart failure (HF), and arrhythmia are frequently observed. Many of these complications are associated with poorer outcomes, including death. Herein we review the relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes among patients with COVID-19, cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19, and cardiovascular complications associated with COVID-19 vaccination.

Keywords: COVID-19, Acute coronary syndrome, Thrombosis, Heart failure

Key points

-

•

Pre-existing cardiovascular comorbidities significantly increase the risk of hospitalization and death secondary to COVID-19 infection.

-

•

Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 include acute coronary syndromes, arterial and venous thrombosis, acutely decompensated heart failure (HF), myopericarditis, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmia.

-

•

COVID-19 vaccination-related cardiac adverse events have been reported, but these occur far less frequently than cardiovascular and other complications related to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Introduction

The Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus, has resulted in unprecedented morbidity and mortality worldwide. Since March 2020, there have been more than 80 million cases, 4 million hospital admissions, and approximately 980,000 deaths in the US alone.1 The US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) emergency use authorization (EUA) of 3 COVID-19 vaccines (Pfizer BioNTech, Moderna, and Janssen/Johnson & Johnson) has led to more than 500 million vaccinations, with 83% of the US population partially and 71% fully vaccinated at the time of writing.2 COVID-19 vaccines offer immense protection, both in reducing the contraction of disease and in reducing the risk of severe illness requiring hospitalization. The risks of testing positive and of dying from COVID-19 are 4 and 15 times higher in unvaccinated individuals than among those who are vaccinated, respectively.

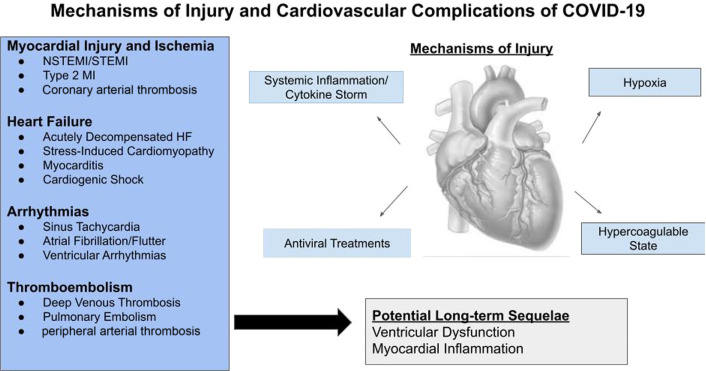

While COVID-19 typically presents as viral pneumonia, cardiovascular manifestations including acute myocardial injury and acute coronary syndromes (ACS), venous and arterial thrombosis, cardiomyopathy, and arrhythmia have all been observed (Fig. 1 ). Herein we review the relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and COVID-19 outcome, and the cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19. Patients with COVID-19, particularly those with underlying comorbidities, are at significant risk for both acute and postrecovery cardiovascular complications.

Association between cardiovascular comorbidities and COVID-19 outcomes

Observational studies published early in the pandemic have suggested that underlying cardiovascular comorbidities and risk factors, including coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure (HF), hypertension (HTN), and diabetes mellitus (DM), were associated with worse outcomes in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 infection.3, 4, 5, 6 In an observational study of 1590 patients admitted with COVID-19 in China, DM [hazard ratio (HR) 1.59 (95% confidence interval (CI):: 1.03–2.45), P = .037], HTN [HR 1.58 (95% CI: 1.07–2.32), P = .022], and the presence of 2 or more preadmission comorbidities [HR 2.59 (95% CI: 1.61–4.17), P < .001] significantly increased the risk of intensive care unit (ICU) admission, invasive ventilation, or death.3 In an analogous observational study of 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area, 56% had HTN, 42% were obese, 11% had CAD, and 7% had underlying HF.6 In a large multicenter database analyzing 132,312 patients with a history of HF who were hospitalized from April 2020 to September 2020%, 6.4% were hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. Nearly 1 in 4 patients with HF hospitalized with COVID-19 died during hospitalization.7 Other cohort studies have also correlated an increased likelihood of ICU level of care4 and worse survival5 among those with overt cardiovascular disease at baseline.

Cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19

Myocardial Injury

The Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction defines acute myocardial injury as a rise and/or fall of cardiac troponin with at least one value > 99th percentile of the upper reference limit without otherwise meeting the criteria for an acute myocardial infarction (symptoms of myocardial ischemia, new ischemic ECG changes, development of pathologic Q waves, imaging evidence suggesting loss of viable myocardium, or the identification of coronary thrombus).8 Given that myocardial injury can occur in the setting of acute stressors such as infection, hypoxemia, anemia, hypotension/shock, acute kidney injury, and congestive HF, it is unsurprising that patients admitted with COVID-19 are frequently found to have myocardial injury.9, 10, 11 The prevalence of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 ranges from 5% to 38%, with an overall crude prevalence of approximately 20%.12

Myocardial injury occurs with relatively higher frequency in patients with COVID-19 who have underlying cardiovascular disease. In a retrospective case series of 187 patients from Wuhan City, China hospitalized with COVID-19, patients with elevated Tn-T levels were more likely to have HTN, CAD, or cardiomyopathy at baseline, compared to those without elevated troponin.9 Similarly, in a cohort of 416 patients admitted with COVID-19, cardiac injury was associated with chronic HTN, DM, CAD, and cerebrovascular disease. In both of the above reports, patients with myocardial injury were more likely to present with abnormal laboratory results including higher elevations in white blood cell counts, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, and creatinine, and with lower levels of platelets and albumin, all of which suggests that those with myocardial injury are more critically ill.9 , 10

The presence of myocardial injury in those with COVID-19 has also been associated with a significant increase in mortality. Guo and colleagues9 observed markedly higher in-hospital adverse events including death, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), malignant arrhythmias, acute coagulopathy, and acute kidney injury in patients with elevated Tn-T levels compared with patients with normal Tn-T. Shi and colleagues10 similarly found that patients with myocardial injury experienced higher rates of mortality, both from time of symptom onset and from index admission date. Additionally, in a study of 179 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, elevated troponin-I (Tn-I) was a predictor of mortality.11 The presence of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 suggests critical systemic illness, and these patients fare poorly even if the criteria for myocardial infarction are absent.

Acute Coronary Syndromes

Acute viral infections, such as SARS-CoV-2, are associated with the activation of inflammatory, prothrombotic, and procoagulant cascades,13 which likely play an important role in the increased risk of ACS through coronary plaque instability and thrombosis.13 At the onset of the pandemic, significant reductions in hospitalizations for chest pain and ACS14 , 15 and an increased incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest were noted.16 Although uncertain, these observations were likely in part related to containment measures implemented to help mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and patient fears of nosocomial COVID-19 infection.

Among patients who did present to hospitals with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) during this time, comorbid conditions, including dyslipidemia, DM, and tobacco use disorder, were more common, and patients were more likely to present with cardiogenic shock.17 While primary PCI remained the gold standard for the treatment of ACS, strained hospital resources, perceived risk to catheterization laboratory personnel, and system delays negatively impacting door-to-balloon time prompted conversations about the use of fibrinolytics for patients presenting with STEMI.18 , 19 In a large observational study evaluating in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized with STEMI, fibrinolytics were used more frequently as reperfusion therapy in patients with COVID-19 than in patients without COVID-19 (0.2% vs 1.9%; P < .001), but their use was still much less common than that of primary percutaneous coronary intervention.20

Patients with STEMI and COVID-19 have increased in-hospital mortality. In a retrospective analysis of 28,189 patients with STEMI in China between December 27, 2019 – February 20, 2020, a higher likelihood of in-hospital mortality [odds ratio (OR): 1.21; (95% CI: 1.07–1.37); P = .003] was observed in those with versus without COVID-19.21 Similarly, in a retrospective cohort study of 80,449 US patients from the Vizient Clinical Database admitted between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2020, rates of in-hospital mortality among patients propensity matched on the likelihood of COVID-19 were higher in those who were COVID-19 positive than COVID-19 negative both for out-of-hospital (15.2% vs 11.2%, P = .007) and in-hospital STEMI (78.5% vs 46.1%; P < .001).20 Additionally, the composite outcome of death, stroke, or MI and the composite outcome of death or stroke were both more frequently observed in the in- and out-of-hospital STEMI cohorts.20 Reassuringly, the mortality rate among patients with STEMI without COVID-19 were similar during the pandemic when compared with 2019, suggesting that alterations in systems of care were not to blame for the increased mortality.20

Thrombotic Complications

Complex interactions between SARS-CoV-2 and platelets, viral-mediated microvascular trauma, proinflammatory cytokine release, and endothelial dysfunction results in micro- and macrovascular complications.22, 23, 24 Markers of systemic inflammation and hypercoagulability are elevated in patients with severe COVID-19, particularly those requiring ICU level of care,4 , 25 and an elevated D-dimer has been shown to independently predict the likelihood of developing an arterial thrombotic event.26 Furthermore, baseline elevations and up-trending D-dimer levels throughout a patient’s hospital course have been associated with increased mortality risk.4 , 5 , 27

Studies have noted a variable but elevated incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.27, 28, 29, 30, 31 The risk of VTE seems to be significantly higher in hospitalized than ambulatory patients with COVID-19.29 In a meta-analysis of 48 studies with a total pooled sample of 18,093 patients, the overall pooled incidence of VTE, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) was 17.0% (95% CI: 13.4–20.9), 12.1% (95% CI: 8.4%–16.4%), and 7.1% (95% CI: 5.3%–9.1%), respectively.32 The incidence of VTE is significantly higher among patients cared for in the ICU compared with a medical ward (27.9% vs 7.1%).32 Other venous thromboses have been reported, including catheter-associated thrombosis,31 renal replacement therapy (RRT) filter thrombosis,33 and portal and mesenteric vein thromboses.34

Arterial thromboembolism including acute ischemic stroke, ACS, acute limb ischemia (ALI), mesenteric, renal, and splenic infarcts have all been documented in patients with COVID-19.26 , 27 , 33 , 35 , 36 In a study of patients with COVID-19 presenting with STEMI, those with COVID-19 were more likely to have multivessel coronary thrombosis, stent thrombosis and more likely to require adjunctive glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor agents, aspiration thrombectomy, and multivessel PCI compared with patients without COVID-19.37 Furthermore, grade 2 to 3 myocardial blush suggesting improved myocardial perfusion was more common in patients without than with COVID-19.37 An observational study from the Lombardi region of Italy noted a significant rise in cases of ALI during a 3-month period compared with the prior year (16.3% vs 1.8%, P < .001).38 Notable predictors of ALI included greater than 50% lung involvement on CT scan, elevated D-dimer, and low fibrinogen.26 Furthermore, in-hospital death was significantly higher in patients with COVID-19 and an acute thrombotic event than in those with COVID-19 but without a thrombotic event (40% vs 16.2%, P = .002); relatedly, those with both a thrombotic event and COVID-19 had a higher in-hospital mortality rate than those with a thrombotic event in the absence of concomitant COVID-19 infection (40% vs 3.1%, P < .001).26

Acute ischemic stroke secondary to large vessel occlusion has also been documented in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.36 In a retrospective, self-controlled case series of 5119 patients with COVID-19 in a Danish hospital, the incidence of ischemic stroke was approximately 10 times higher (incidence ratio 12.9 [95% CI: 7.1–23.5; P < .001)] when compared with patients during a pre–COVID-19 control time interval.36 A higher rate of stroke has been observed in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 than influenza.39 Importantly, however, in a retrospective study of 8163 patients, only 1.3% with symptomatic COVID-19 and 1.0% of asymptomatic COVID-19 developed an acute ischemic stroke, suggesting that while the relative risk of stroke is significantly increased, the absolute risk remains low.40 Nonetheless, in this cohort, in-hospital mortality was significantly higher following acute ischemic stroke in those with COVID-19 than without COVID-19 (19.4% vs 6.2%, P < .0001%).40

Heart Failure and Cardiogenic Shock

Patients with chronic HF are particularly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Early in the pandemic, reductions in ED visits and hospitalizations for acute decompensated HF were noted.41 , 42 Despite these reductions, chronic HF remained an important risk factor for admission in patients with COVID-19.43

In-hospital complications including death were more frequently observed in patients with underlying HF admitted for COVID-19.44 , 45 In a study of 6439 patients admitted with COVID-19, the risk of ICU admission [adjusted OR: 1.71; (95% CI: 1.25–2.34); P = .001], intubation and mechanical ventilation [adjusted OR: 3.64; (95% CI: 2.56–5.16); P < .001, and in-hospital mortality [adjusted OR: 1.88; (95% CI: 1.27–2.78); P = .002] were significantly higher in patients with than without pre-existing HF.44 Notably, risk was similar irrespective of whether patients had HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) or HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).44 In a meta-analysis of 18 studies, mortality in patients with both COVID-19 and pre-existing HF was significantly higher than in patients with COVID-19 without pre-existing HF [OR: 3.46; (95% CI: 2.52–4.75); P < .001].45

Myocarditis with or without pericardial involvement (myopericarditis) is an uncommon but well-documented complication of viral infection and can result in hospitalization, HF, arrhythmia, and sudden death.46 Myocarditis has been reported secondary to influenza47 and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)48 in previously healthy patients. Pathologic mechanisms responsible for viral myocarditis are hypothesized to include a postviral autoimmune reaction, antigenic mimicry, and direct immune injury with cytokine storm.49 , 50 Presenting signs and symptoms of acute myocarditis are nonspecific (dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, peripheral edema, presyncope/syncope) and can delay diagnosis. In patients with suspected acute myocarditis, diagnostic strategies should include the assessment of cardiac biomarkers, inflammatory markers, and echocardiographic evaluation of ventricular function.

There have been many reports of COVID-19-associated myocarditis since the onset of the pandemic.51 Using a large, US hospital-based administrative database from more than 900 hospitals, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) assessed the association between COVID-19 and myocarditis and observed that patients with COVID-19 were approximately 15 times more likely to be diagnosed with myocarditis than those without COVID-19.52 COVID-19-related myocarditis seems to have a male predominance and can occur irrespective of comorbid conditions.53 Furthermore, myocardial injury, reductions in left ventricular (LV) systolic function, pericardial effusions with or without tamponade physiology, and cardiogenic shock have all been documented.53 , 54

Stress-induced (“Takotsubo”) cardiomyopathy with apical ballooning has also been documented in patients with COVID-19. Case reports have described this complication in both male and female patients with and without pre-existing comorbidities.55 Proposed etiologic mechanisms are similar to those of acute myocarditis including an exaggerated immune response with cytokine storm, overstimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, and microvascular dysfunction.55 Documented complications of stress-induced cardiomyopathy include LV dysfunction, cardiogenic shock, LV thrombus, dynamic LV outflow tract obstruction, QT prolongation, atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, pericardial effusions, and death.56

Cardiac Arrhythmias

Both atrial and ventricular arrhythmias are commonly observed in patients with COVID-19. Palpitations have been reported as the presenting symptom in 10% of patients,57 and sinus tachycardia has been documented as the most common cardiac rhythm disturbance, likely as a physiologic compensation mechanism to acute illness.58 An early report from China noted that 17% of their total cohort and 44% of patients requiring ICU level of care had documented arrhythmia4; however, in a larger cohort of 700 patients admitted to a Pennsylvania hospital with COVID-19, no cases of heart block, sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), or ventricular fibrillation (VF) were noted, and only 9 episodes of clinically significant bradyarrhythmia resulting in hypotension, 25 incidents of atrial fibrillation requiring amiodarone and diltiazem, and 10 nonsustained VT episodes were observed.59

Atrial fibrillation and flutter (AF) are the most commonly encountered cardiac dysrhythmias in the United States60 and are associated with an increased risk of stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), and other arterial emboli. Both the risk of mortality61 and thromboembolic complications62 are higher among patients with COVID-19 who also have preexisting AF. In a large systematic review and analysis of 19 studies totaling 21,653 patients hospitalized with COVID-19, the pooled prevalence of AF was 11%. In subgroup analysis, patients ≥ 60 years old exhibited a 2.5-fold higher prevalence, and patients with severe COVID-19 had a 6-fold higher prevalence of AF compared with younger and less critically ill patients, respectively.63 The use of pre-admission oral anticoagulation (OAC) with either a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) or vitamin K antagonist (VKA) in patients with AF admitted with COVID-19 has been associated with lower composite rates of in-hospital death or thrombotic events, and less severe COVID-19. These observations, while hypothesis generating, may suggest that subclinical and clinical thrombosis are prevented by the use of pre-admission OAC.64

The initial EUA of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19 sparked concern regarding the risk of QT prolongation and Torsade de Pointes. However, subsequent studies observed modest QT/QTc prolongation, with low rates of major ventricular arrhythmia rates and no-arrhythmia-related deaths. Furthermore, in retrospective studies65 and prospective randomized controlled trials,66 the use of hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin did not improve clinical status or mortality. As a result, hydroxychloroquine has fallen out of favor.

COVID-19 vaccines

COVID-19 vaccine-induced complications have been described following the release of COVID-19 and adenoviral-vector vaccines. Cases of presumed vaccine-induced pericarditis and myocarditis confirmed by cardiac MRI have been observed in otherwise healthy adolescents and young adults within days of vaccination.67 , 68 Large observational studies subsequently confirmed a very low incidence of vaccine-associated myocarditis, seen more commonly among White males.69 , 70 Other cardiovascular complications after COVID-19 adenoviral vector vaccines (eg, AstraZeneca and Janssen/Johnson & Johnson) have been reported including immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (TTS),71 cerebral venous sinus thrombosis,71 VTE, TIA and stroke, acute myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and large-vessel vasculitis including Kawasaki disease.72 Nonetheless, these complications are rare and occur much less commonly than following SARS-CoV-2 infection.73

Long-term consequences of COVID-19

The long-term cardiovascular effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection have not been fully established and remain a focus of ongoing studies. Using a national cohort of 153,760 patients from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Xie and colleagues74 observed that prior infection with COVID-19 was associated with an increased incidence of cerebrovascular disorders, dysrhythmias, pericarditis, myocarditis, ischemic heart disease, HF, and thromboembolic events 1 year after infection, when compared with both contemporary and historical control groups. Notably, the increase in cardiovascular complications was observed regardless of whether patients had a history of prior cardiovascular disease and regardless of whether they required hospitalization or ICU admission during active infection. Nevertheless, the severity of initial SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with the likelihood of postinfection cardiovascular complications.74

Long-COVID, a term used to describe persistent symptoms after recovery from acute COVID-19 infection, is also being closely investigated. Symptoms including fatigue, sleep disturbances, nonspecific chest pain, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal upset have all been reported. Quantitative findings supportive of multi-organ involvement have been documented, including abnormalities in liver enzymes, acute kidney injury, reductions in circulating T and B lymphocytes, and elevated troponin.75 Long-term follow-up of patients with long-COVID is needed to better understand the consequences of COVID-19 infection.

Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant morbidity and mortality worldwide. There has been increasing progress in understanding and defining cardiovascular manifestations of COVID-19 illness. Patients hospitalized with COVID-19, particularly those with underlying cardiovascular comorbidities, are at high risk for developing serious cardiovascular manifestations such as acute myocardial injury and ACS, HF and cardiogenic shock, systemic thromboembolism, and arrhythmia. A thorough understanding of these complications may better prepare clinicians and improve patient outcomes.

Clinics care points

-

•

Patients with cardiovascular risk factors and overt cardiovascular disease are more likely to be hospitalized, have more severe disease, and experience poorer outcomes in the setting of COVID-19.

-

•

COVID-19 vaccination is essential among patients with cardiovascular risk factors and overt disease to ameliorate these risks.76

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

This article originally appeared in Cardiology Clinics, Volume 40, Issue 3, August 2022.

References

- 1.CDC - Cases, Deaths, & Testing. Available at: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days. Accessed February 25, 2022.

- 2.CDC – COVID Data Tracker COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations_vacc-total-admin-rate-total Available at: Acessed February 25, 2022.

- 3.Guan W jie, hua Liang W., Zhao Y., et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with COVID-19 in China: a nationwide analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000547. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson S., Hirsch J.S., Narasimhan M., et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt A.S., Jering K.S., Vaduganathan M., et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure hospitalized with COVID-19. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9(1):65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., Jaffe A.S., et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., et al. Cardiovascular Implications of fatal outcomes of patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7):802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du R.H., Liang L.R., Yang C.Q., et al. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000524. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bavishi C., Bonow R.O., Trivedi V., et al. Acute myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63(5):682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandoval Y., Januzzi J.L., Jaffe A.S. Cardiac troponin for the diagnosis and risk-stratification of myocardial injury in COVID-19: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(10):1244–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filippo O.D., D’Ascenzo F., Angelini F., et al. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during Covid-19 outbreak in northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(1) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helal A., Shahin L., Abdelsalam M., et al. Global effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the rate of acute coronary syndrome admissions: a comprehensive review of published literature. Open Heart. 2021;8(1):e001645. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2021-001645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai P.H., Lancet E.A., Weiden M.D., et al. Characteristics associated with out-of-hospital cardiac arrests and resuscitations during the novel Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in New York City. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(10):1154–1163. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia S., Dehghani P., Grines C., et al. Initial findings from the North American COVID-19 myocardial infarction registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(16):1994–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang N., Zhang M., Su H., et al. Fibrinolysis is a reasonable alternative for STEMI care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(10) doi: 10.1177/0300060520966151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels M.J., Cohen M.G., Bavry A.A., et al. Reperfusion of ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction in the COVID-19 era. Circulation. 2020;141(24):1948–1950. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saad M., Kennedy K.F., Imran H., et al. Association between COVID-19 diagnosis and in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2021;326(19):1940–1952. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang D., Xiang X., Zhang W., et al. Management and outcomes of patients with STEMI during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(11):1318–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page E.M., Ariëns R.A.S. Mechanisms of thrombosis and cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2021;200:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miesbach W., Makris M. COVID-19: coagulopathy, risk of thrombosis, and the rationale for anticoagulation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620938149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goshua G., Pine A.B., Meizlish M.L., et al. Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: evidence from a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(8):e575–e582. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fournier M., Faille D., Dossier A., et al. Arterial thrombotic events in adult inpatients with COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(2):295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilaloglu S., Aphinyanaphongs Y., Jones S., et al. Thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a New York City health system. JAMA. 2020;324(8):799–801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middeldorp S., Coppens M., Haaps TF van, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roubinian N.H., Dusendang J.R., Mark D.G., et al. Incidence of 30-day venous thromboembolism in adults tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection in an integrated health care system in Northern California. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(7):997–1000. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodigiani C., Iapichino G., Carenzo L., et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez D., Garcia-Sanchez A., Rali P., et al. Incidence of VTE and bleeding among hospitalized patients with Coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2021;159(3):1182–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F., et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry O de, Mekki A., Diffre C., et al. Arterial and venous abdominal thrombosis in a 79-year-old woman with COVID-19 pneumonia. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15(7):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah A., Donovan K., McHugh A., et al. Thrombotic and haemorrhagic complications in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multicentre observational study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):561. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03260-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oxley T.J., Mocco J., Majidi S., et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choudry F.A., Hamshere S.M., Rathod K.S., et al. High thrombus burden in patients with COVID-19 presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(10):1168–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bellosta R., Luzzani L., Natalini G., et al. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(6):1864–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merkler A.E., Parikh N.S., Mir S., et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(11):1366–1372. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qureshi A.I., Baskett W.I., Huang W., et al. Acute ischemic stroke and COVID-19. Stroke. 2020;52(3):905–912. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frankfurter C., Buchan T.A., Kobulnik J., et al. Reduced rate of hospital presentations for heart failure during the Covid-19 pandemic in Toronto, Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36(10):1680–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cox Z.L., Lai P., Lindenfeld J. Decreases in acute heart failure hospitalizations during COVID-19. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(6):1045–1046. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrilli C.M., Jones S.A., Yang J., et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez-Garcia J., Lee S., Gupta A., et al. Prognostic impact of prior heart failure in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(20):2334–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yonas E., Alwi I., Pranata R., et al. Effect of heart failure on the outcome of COVID-19 — a meta analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kindermann I., Barth C., Mahfoud F., et al. Update on myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(9):779–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar K., Guirgis M., Zieroth S., et al. Influenza myocarditis and myositis: case presentation and review of the literature. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(4):514–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alhogbani T. Acute myocarditis associated with novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36(1):78–80. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maisch B., Ristić A.D., Hufnagel G., et al. Pathophysiology of viral myocarditis the role of humoral immune response. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2002;11(2):112–122. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(01)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawakami R., Sakamoto A., Kawai K., et al. Pathological evidence for SARS-CoV-2 as a cause of myocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(3):314–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rathore S.S., Rojas G.A., Sondhi M., et al. Myocarditis associated with Covid-19 disease: a systematic review of published case reports and case series. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(11):e14470. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehmer T.K., Kompaniyets L., Lavery A.M., et al. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data - United States, March 2020-January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(35):1228–1232. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawalha K., Abozenah M., Kadado A.J., et al. Systematic review of COVID-19 related myocarditis: insights on management and outcome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;23:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mele D., Flamigni F., Rapezzi C., et al. Myocarditis in COVID-19 patients: current problems. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16(5):1123–1129. doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02635-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah R.M., Shah M., Shah S., et al. Takotsubo syndrome and COVID-19: associations and implications. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46(3):100763. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moady G., Atar S. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy—considerations for diagnosis and management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Medicina. 2022;58(2):192. doi: 10.3390/medicina58020192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu K., Fang Y.Y., Deng Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus cases in tertiary hospitals in Hubei Province. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(9):1025–1031. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cho J.H., Namazi A., Shelton R., et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a prospective observational study in the western United States. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bhatla A., Mayer M.M., Adusumalli S., et al. COVID-19 and cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(9):1439–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeLago A.J., Essa M., Ghajar A., et al. Incidence and mortality trends of atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter in the United States 1990 to 2017. Am J Cardiol. 2021;148:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen M.Y., Xiao F.P., Kuai L., et al. Outcomes of atrial fibrillation in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrison S.L., Fazio-Eynullayeva E., Lane D.A., et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of 30-day incident thromboembolic events, and mortality in adults ≥ 50 years with COVID-19. J Arrhythm. 2020;37(1):231–237. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Z., Shao W., Zhang J., et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated mortality among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:720129. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.720129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Louis D., Kennedy K., Saad M., et al. Pre-admission oral anticoagulation is associated with fewer thrombotic comlpications in patients admitted with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(9S):1798. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosenberg E.S., Dufort E.M., Udo T., et al. Association of Treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York State. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2493–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cavalcanti A.B., Zampieri F.G., Rosa R.G., et al. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2041–2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patel Y.R., Louis D.W., Atalay M., et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in young adult patients with acute myocarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: a case series. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2021;23(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s12968-021-00795-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shaw K.E., Cavalcante J.L., Han B.K., et al. Possible association between COVID-19 vaccine and myocarditis: clinical and CMR findings. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14(9):1856–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Witberg G., Barda N., Hoss S., et al. Myocarditis after Covid-19 vaccination in a large health care organization. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oster M.E., Shay D.K., Su J.R., et al. Myocarditis cases reported after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccination in the US from December 2020 to August 2021. JAMA. 2022;327(4):331–340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.24110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kammen MS van, Sousa DA de, Poli S., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine–induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(11):1314–1323. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cari L., Alhosseini M.N., Fiore P., et al. Cardiovascular, neurological, and pulmonary events following vaccination with the BNT162b2, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines: an analysis of European data. J Autoimmun. 2021;125:102742. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patone M., Mei X.W., Handunnetthi L., et al. Risks of myocarditis, pericarditis, and cardiac arrhythmias associated with COVID-19 vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01630-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xie Y., Xu E., Bowe B., et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crook H., Raza S., Nowell J., et al. Long covid—mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021;374:n1648. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leong D.P., Banerjee A., Yusuf S. COVID-19 vaccination prioritization on the basis of cardiovascular risk factors and number needed to vaccinate to prevent death. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37(7):1112–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]