Abstract

A key function of dendritic cells (DCs) is to induce either immune tolerance or immune activation. Many new DC subsets are being recognized, and it is now clear that each DC subset has a specialized function. For example, different DC subsets may express different cell surface molecules and respond differently to activation by secretion of a unique cytokine profile. Apart from intrinsic differences among DC subsets, various immune modulators in the microenvironment may influence DC function; inappropriate DC function is closely related to the development of immune disorders. The most exciting recent advance in DC biology is appreciation of human DC subsets. In this review, we discuss functionally different mouse and human DC subsets both in lymphoid organs and non-lymphoid organs, the molecules that regulate DC function, and the emerging understanding of the contribution of DCs to autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Dendritic cells, Tissue-resident dendritic cells, Tolerogenic dendritic cells, Autoimmunity

1. Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are potent antigen presenting cells (APCs) and play an important role in regulating T cell function. DCs can be distinguished from other immune cells by surface markers. They are derived from common myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow but then diverge from other myeloid cells along specific differentiation pathways. Although DCs are fewer in number than lymphocytes, they are present throughout the body and are crucial sentinels for invading pathogens. Soon after the identification of DCs in lymphoid organs, DCs with functional specificity were recognized to be present in various mucosal tissues as well as in each solid organ. DCs are composed of functionally heterogeneous subsets, whose function can be further modulated by environmental stimuli. Abnormalities in the differentiation and function of DCs can directly cause various immune disorders. This review will discuss major advances in our understanding of conventional DC (cDC) subsets and the contribution of DC dysregulation to immune diseases, especially autoimmune diseases. Another major DC subset, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) will not be discussed in detail. The review will also focus on intestinal DCs as an example of non-lymphoid DCs since growing evidence demonstrates that the intestinal immune response closely communicates with the systemic immune system.

2. DC differentiation and turn-over rate

2.1. Differentiation

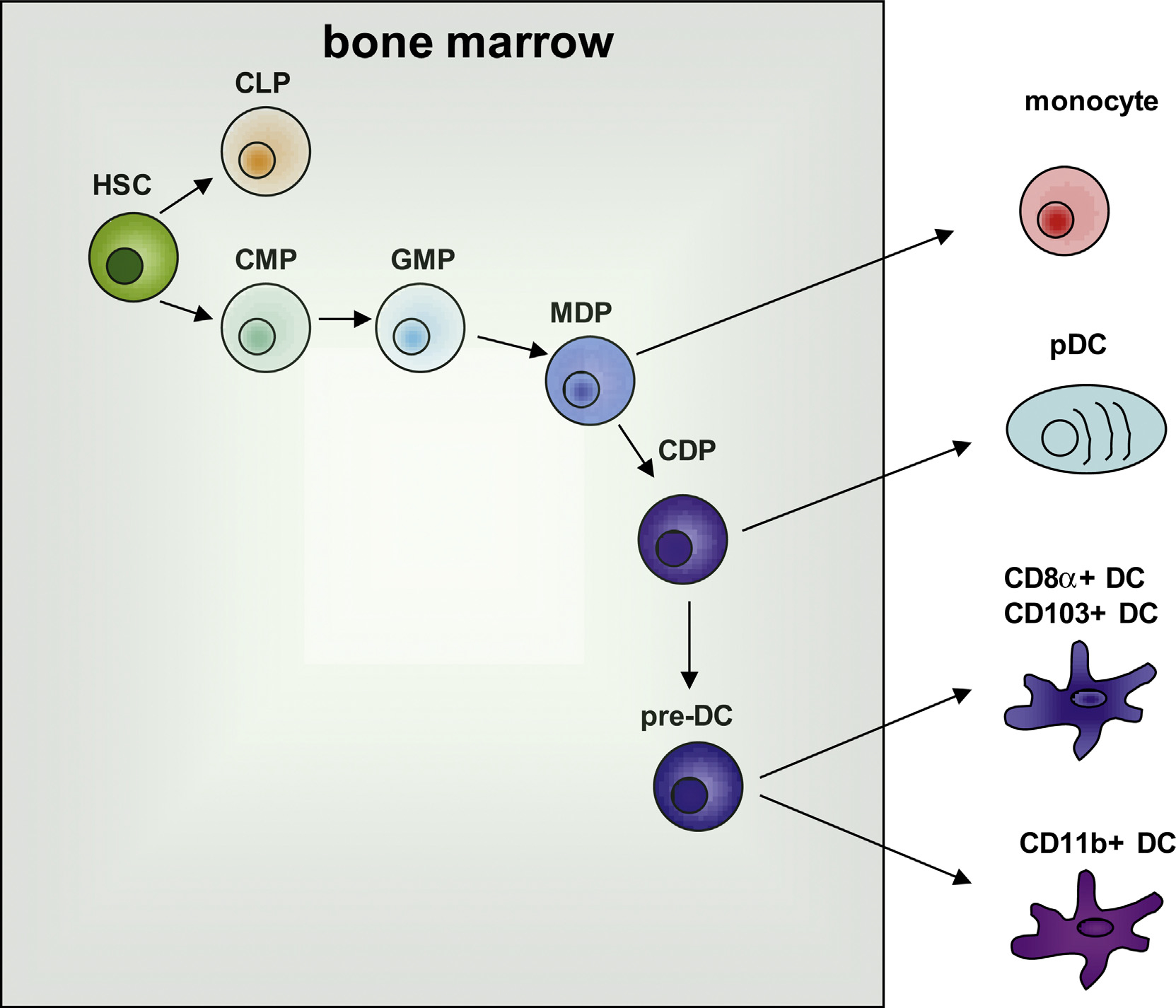

With the exception of epidermal Langerhans cells that are derived from fetal liver and york sac-derived myeloid progenitors [1], it is generally accepted that DCs are derived from bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells (Fig. 1). Most cDCs arise from a hematopoietic lineage that is distinct from the precursor for other leukocytes. The identification of DC-progenitors has relied on adoptive transfer studies and fate mapping studies using genetic models. In the bone marrow, early DC-precursors, common DC precursor cells (CDPs; Lin-Sca1-IL7Rα-CD16/32lowc-kitintCD11b-CD115+CD135+) can be differentiated from macrophage DC precursor cells (MDP; Lin-Sca1-IL7Rα-CD16/32hic-kit+CX3CR1+CD11b-CD115+CD135+). Adoptive transfer of MDPs into irradiated mice can reconstitute spleen macrophages, lymphoid and non-lymphoid resident cDCs and, to some extent, pDCs [2–4]. In contrast, CDPs give rise to spleen and lymph node (LN) cDCs, pDCs and non-lymphoid resident cDCs, but not to macrophages [3,5]. Studies in parabiotic mice confirmed that CDPs are immediately downstream of MDPs [6]. These studies demonstrated that CDPs are the first dedicated precursors of DCs. CDPs give rise to a cell termed precursor of cDCs (pre-cDCs; CD11c+MHCII−) and pDCs (CD11cintSiglec-H+) that migrate from the bone marrow to lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissue [6,7]. Pre-cDCs can differentiate in the periphery, giving rise to CD8α+ and CD11b+ cDCs but not pDCs in spleen and LNs [6]. Pre-cDCs also produce CD103+CD11b− cDCs and CD103+CD11b+ cDCs in the intestine [3,4]. Although cDCs show functional plasticity upon environmental stimulation, there is no clear evidence for reversibility in fate decision among the terminally differentiated DC subsets. While one study shows that DC subset fate decision is not interchangeable under the steady state condition [8], it is not fully determined whether this is also true under inflammatory conditions.

Fig. 1.

DC commitment and differentiation. The illustration shows that DCs and monocytes originated from a common myeloid progenitor (CMP) which is derived from hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). HSCs give rise to common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) and CMPs. CMPs differentiate into granulocyte macrophage progenitors (GMPs), which differentiate into granulocyte and macrophage DC progenitors (MDP). MDPs give rise to monocytes and common DC progenitors (CDP), and CDPs further differentiate into plasmacytoid DCs (pDC) or pre-DCs. Pre-DCs can migrate out of bone marrow and undergo final differentiation into CD8α+ DCs or CD11b+ DCs in lymphoid organs or CD103+ DCs or CD11b+ DCs in non-lymphoid tissue. Shaded box represents bone marrow.

2.2. DC turn-over rate

Homeostasis of DCs in lymphoid and non-lymphoid tissues is maintained by constant replacement with new cells. In vivo studies with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling and results from studies of parabiotic mice have revealed that 5% of LN DCs and pre-cDCs are actively cycling, repopulating the cDC pool [6,9]. Although pre-cDCs proliferate locally with a small burst size in the absence of Tregs, they do not self-renew in the steady state and are continuously replaced by cells from the blood [10–12]. Reconstitution of DCs in different organs occurs at different rates. For example, DCs in the spleen are entirely replaced by bone marrow derived cells in 10–14 days, while DCs in the intestine are more rapidly replaced [3].

3. Functional classification of DCs

DCs play a role in both the initiation of an antigen (Ag)-specific immune response and the maintenance of immune tolerance. Their maturation stage (immature versus mature) and functional capacity (immunogenic versus tolerogenic) are critical factors in the subsequent immune response as is the form of Ag and the place where Ag is encountered. Moreover, the DC subset that encounters Ags is also a critical determinant in decisions of immunological consequence. There are several subsets of DCs presently classified by developmental stage, phenotype, and location including cDCs (CD8α+ DC and CD11b+ DCs in spleen, CD103+CD11b− DCs and CD103+CD11b+ DCs in tissues) and pDCs. Depending on the local micro-environment and on inflammatory stimuli, tissue-resident immature tolerogenic DCs with functional plasticity may differentiate into immunogenic DCs. Tolerogenic DCs induce immune silence to encountered Ag; however, tolerogenic DCs can become immunogenic DCs when stimulated to undergo maturation. Proper regulation of tolerogenic DCs and immunogenic DCs is critical, since abnormal or prolonged generation of these DC subsets is closely related to the development of immunodeficiency or autoimmune diseases.

3.1. Inflammatory DCs

Inflammatory DCs are a population of DCs that are transiently formed in response to microbial infection or inflammatory stimuli. Multiple subsets of inflammatory DCs have been characterized in mice. Initially, inflammatory DCs were all believed to be monocyte-derived cells, but DC-precursor-derived-inflammatory DCs were later identified under different inflammatory conditions. Monocyte-derived inflammatory DCs differentiate from Ly6Chi monocytes, and disappear once inflammation has resolved. TNFα/iNOS-producing DCs (TipDCs) are a well characterized example of monocyte-derived inflammatory DCs; they are generated in animals infected with Listeria monocytogenes [13]. Although they are named DCs, TipDCs are not considered to be genuine DCs due to their lack of expression of the DC-specific zinc finger transcription factor, zbtb46. Furthermore, they develop normally in zbtb46-diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) mice treated with DT, suggesting that they are more closely related to activated monocytes or macrophages [14,15] than to DCs. Differentiation of TipDCs appears to require IFNγ-producing TH1 cells [16] and Toll-like receptor (TLR)4- or TLR9-mediated MyD88-dependent signaling [17]. TipDCs are beneficial in the clearance of intracellular pathogens and parasites [18]. In addition to TipDCs, Ly6C+CD11b+MHCII+CD11cint-inflammatory DCs (Ly6C+ inflammatory DCs) arise from Ly6Chi circulating monocytes [19,20]. Ly6C+ inflammatory DCs accumulate in the LN in response to LPS injections and express the lectin DC-SIGN and the mannose receptor CD206 [21,22]. Although they express a high level of the monocyte marker, Ly6C, LPS-induced inflammatory DCs are considered to be bona fide DCs since they express zbtb46 and because their development is dependent on Flt3L or zbtb46 in mice [14,15].

Inflammatory DCs clearly demonstrate potent TH1 stimulatory function. CD11c+CD11bhiGr-1+ inflammatory DCs (Gr-1+ inflammatory DCs) produce IL-12 p70 and stimulate IFNγ-producing TH1 cells. This subset of DCs is enriched in plt (‘paucity of lymph node T cells’) mice due to the low number of other subsets of DCs in LNs. The representation of DCs in other organs in this strain has not been reported [23]. Until recently, it was not clear whether inflammatory DCs also trigger the differentiation of TH17 cells. However, a recent study identified another inflammatory DC subset, E-cadherin+ DCs, that induces severe pathology in colitis with a higher number of IL-17+ CD4+ T cells, suggesting a role for inflammatory DCs in the induction of TH17 type responses [24].

3.2. Tolerogenic DCs

Tolerogenic DCs induce immune tolerance mainly by modulation of T cell activation. They participate in both central tolerance and peripheral tolerance. It has been demonstrated experimentally that thymic DCs can delete or silence (anergize) autoreactive T cells [25,26]. Since central tolerance is incomplete, however, there is a need for peripheral tolerance. Peripheral tolerance occurs in various locations, including peripheral lymphoid organs as well as tissues. Therefore, the mechanisms to accomplish peripheral tolerance are complicated and various types of DCs participate in these processes. At steady-state, tissue-resident immature DCs readily uptake and present antigens from their environment; they are poorly immunogenic due to a lack of proinflammatory cytokine production and a low level of co-stimulatory molecule expression. In mouse experiments, the CD8α+ subset of splenic DCs and CD103+ DCs in intestinal lamina propria (LP) and mesenteric LNs uptake dying cells and cross-present cell-associated antigens leading to tolerance of CD8+ T cells [27,28].

DCs also contribute to tolerance through the induction of regulatory T cells (Treg) [29]. Tregs suppress effector functions of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, contributing a critical layer of immune tolerance [30]. The repetitive stimulation of T cells with immature DCs generates IL-10 producing Tregs in vitro [31]. IL-10 or TGFβ produced by DCs are key soluble inducers of Treg differentiation, and various subsets of immature or mature DCs from lymphoid organs and non-lymphoid organs can secrete those cytokines [32–34]. Indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression in DCs is another mechanism of immune tolerance since IDO inhibits effector T cell proliferation [35]. PDCs were first identified as major IDO producing DCs, and, following this observation, intestinal LP CD103+ DCs were also found to express IDO. Intestinal LP CD103+ DCs produce retinoic acid (RA) together with IDO, and these molecules are critical for Treg differentiation in the intestine [36,37]. Some skin-derived DCs can also produce RA [38], and IDO expression is inducible in DCs by a variety of environmental signals, including TGFβ, IFNγ, and engagement of glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein (GITR) [38–40]. Therefore, DCs can adapt environmental inputs to acquire or sustain tolerogenic capacities.

4. Regulators of tolerogenic DCs function

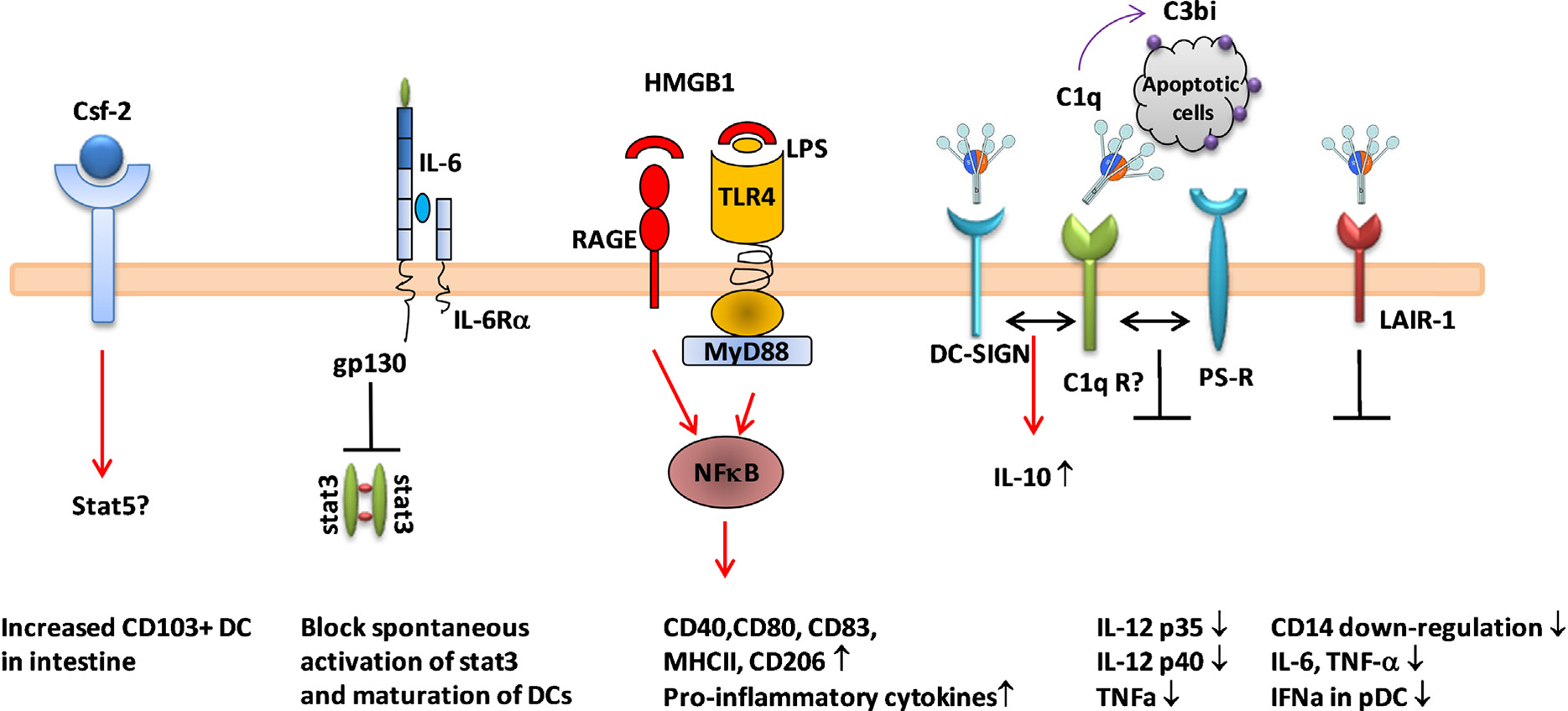

Due to a critical contribution to immune responses, DC function is expected to be tightly regulated under steady state and inflammatory conditions. Concordant with the role of DCs in homeostasis, there are various factors involved in fine tuning of DC function, including intrinsic regulators (transcription factors) and extrinsic regulators (Fig. 2). Although numerous regulators have been identified in various DC activation pathways, our discussion will be focused on transcription factors and soluble factors whose function is directly related to DC function. In most cases, as expected, a specific defect of each regulator (separately or in combination) leads to abnormalities in animals and humans.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of DC function by soluble factors. Various soluble proteins regulate function of DCs. Csf-2 which is expressed during inflammation, binds to Csf-2 receptor in DCs leading to increase CD103+ cDC survival. Csf-2R engagement also increases CD103 expression in cDCs in a stat5-dependent fashion. A low level of circulating IL-6 can trigger gp130 activation and inhibit stat3 activation in DCs. This signaling is required to maintain an immature DC phenotype. HMGB1 secreted from necrotic cells can bind to RAGE or TLR4 on the surface of DCs, and activate NFκB signaling pathway leading to upregualtion of co-stimulatory molecule expression and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Regulation by C1q on DCs occurs through multiple receptors. C1q can bind to C1q receptors (gC1qR, C1qRp and collectin), DC-SIGN, collagen receptor, LAIR-1 and dispose of apoptotic debris. C1q binding to C1q receptors might execute signaling alone or by cross-talk between receptors. The consequence of C1q binding to receptors is downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine expression and blocking of monocytes to DC differentiation.

4.1. Transcription factors

Transcriptional profiling has shown that several transcription factors have critical roles in DC function (Table 1). Interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 8 (also known as IFN consensus sequence-binding protein: ICSBP) is an important transcription factor for myeloid cell differentiation [41,42]. In addition to its role in DC development, IRF8 controls type I IFN production following viral infection and IL-12 p40 or IL-15 production in CD11c+ DCs. IRF8-deficient DCs display phenotypic alterations in costimulatory molecules and chemokine receptor expression resulting in impaired Ag-specific T cell activation [43]. Expression of IRF8 is also required for the acquisition of IDO competence in murine CD8α+ DCs [44].

Table 1.

Transcription factors regulating DC function.

| Gene | Deletion protocol | DC population | Phenotype | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| T-bet | Null mice in RAG2−/− (BALB/c) | NC | Severe ulcerative colitis and colorectal | Increased expression of TNFα in intestinal DCs response to commensal bacteria | [143] |

| Stat3 | CD11c-CRE | pDC, CD8α+ and CD8α− cDC ↓↓↓ | Spontaneous development of cervical lymphadenopathy and mild ileocolitis | Hyper activation of antigen specific T cell activation and due to increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines and refractoryto IL-10 mediated DC suppressive feedback | [46] |

| Prdm1 (BLIMP-1) | CD1c-CRE | Normal development CD8α+ cDC↑ in spleen, CD103+ cDC↑ in intestine LP | Spontaneous development of SLE-like disease due to increased germinal center reaction | Increased secretion of IL-6 upon TLR activation and preferential differentiation of follicular helper T cells by DCs | [52] |

| Foxo3 | Null mice (C57BL/6) | pDc, CD8α+ and CD11b+ cDC↑ | Abnormal expansion of T cell response to viral infection | Increased T cell survival due to IL-6 from DCs | [144] |

| Nf-κb1 | Null mice in RIP-gp Transgenic mice | CD11c+ cDC and pDC ↓ in spleen | Spontaneous development of diabetes | TNFα dependent disruption of CD8+ T cell tolerance | [145] |

| RelB | Null mice | CD8α− cDC ↓ in spleen and LN | Lack of helper T cell priming and cross-presentation | Lack of upregulation of costimulatory molecules, MHCII, CD80 and CD40 | [146] |

| Irf1 | Null mice | NC | Inefficient priming of TH1 cells | Required for optimal production of IFNβ, iNOS, and IL-12 p35 in IFNγ treated cells | [147] |

| Irf7 | Null mice | NC | ND | Hyper activation of DCs in response to TLR2 activation with low IL-12 and high IL-10 production | [148] |

| Irf8 | Null mice | pDC, CD8α+ cDC, CD103+ cDC ↓↓↓ | Susceptible to viral infection (NDV) | DCs fail to produce IFNα or IL-12p40 in response to viral infection | [43] |

NC, not changed; ND, not determined.

Zinc finger protein, Gfi1, determines myeloid cell differentiation at the point of the bifurcation of macrophages and DCs through the regulation of another transcription factor, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3). Gfi1-deficient mice have a markedly reduced number of all DCs in lymphoid organs. The DCs that are present in Gfi1-deficient mice display functional abnormalities, including reduced expression of MHCII molecules, lack of induced expression of co-stimulatory molecules, and failure to activate Ag-specific T cell [45]. Stat3 conditional knockout (CKO) mice generated by CD11c-cre transgene expression develop cervical lymphadenopathy and ileocolitis demonstrating that STAT3 is a cell-intrinsic negative regulator linked to chronic mucosal inflammation [46]. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (Ppar-γ) is ubiquitously expressed in immune cells and has been shown to regulate inflammatory responses in DCs by reducing expression of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-12, IL-15, TNFα and IL-6 [47,48].

Another transcriptional repressor, B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (BLIMP-1) has also been shown to regulate DC function. Expression of BLIMP-1 is up-regulated in activated DCs through p38 MAPK and NFκB pathways, and controls DC homeostatic function by regulating several genes, including IL-6, MHC II transactivator (CIITA) and microRNA let-7c [49–51]. BLIMP-1-deficient DCs show an increased level of MHC II, pro-inflmmatory cytokines and chemokines and DC restricted BLIMP-1 CKO mice develop autoantibodies in a gender and strain dependent manner [52]. Recently, B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6), a counter regulator of BLIMP-1, has been shown to be required for CD4+ and CD8α+ cDC development in the periphery [53], however, its role in DC function has not been fully investigated.

4.2. Soluble regulators

Various cytokines are known to regulate DC function. Colony stimulating factor 2 (CSF-2, GM-CSF) acts in the steady state to promote survival of tissue-resident CD103+ and CD11b+ DCs and is critical for cross-presentation which is needed for CD8+ T cell activation in vivo [54]. CSF-2 also regulates CD103 expression on tissue DCs, suggesting that it is involved in the final stage of DC differentiation and in the acquisition of the capacity to cross-present antigen [54,55]. A low basal level of IL-6 is required for the maintenance of immature DCs for regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation [56]. In mature DCs, IL-6 can inhibit the LN homing receptor, CCR7, through NFκB signaling and IL-10 secretion [57]. Interestingly, estrogen is required for increased production of IL-6 in splenic cDCs which contribute for development of lupus-like phenotype (S.J. Kim and B. Diamond personal observation). These data clearly suggest that a tight regulation of IL-6 expression is required for controlling DC phenotype under both steady state and inflammatory conditions.

High-mobility group B1 protein (HMGB1) is an endogenous immune adjuvant released by necrotic cells and by inflammatory cells. HMGB1-deficient cells have a reduced ability to activate DCs and macrophages [58]. HMGB1, through binding to the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE), and perhaps TLR4, both receptors of HMGB1, is a functional regulator of DCs, with a positive role in type I IFN secretion in human pDCs [59] and in induction of phenotypic maturation of DCs with increased CD83, CD80, CD40, MHCII, and decreased CD206 expression [60]. The B-box domain of HMGB1 is functionally responsible for increased expression of co-stimulatory molecules and pro-inflammatory cytokines, favoring TH 1 polarization [60]. Although RAGE is the most studied HMGB1 receptor, some reports indicate that TLR4 can directly recognize HMGB1 and this interaction results in secretion of TNFα [61]. A recent study demonstrated an immunogenic function of HMGB1 in intestinal LP DCs, as HMGB1 facilitated an early activation and differentiation of CD11c+CD11b+Ly6Chi inflammatory DCs for CD8α+ T cell activation against neoplastic cells [62,63].

Complement components, especially the early complement component C1q, are known to exert immunoregulatory functions on DCs. The complement cascade is a critical pathway involved in protecting the host against infection. It functions by opsonizing pathogens, facilitating uptake by phagocytes and generating components (C3 and C5 to C3b and C5a, respectively) that bring inflammatory immune cells to the infected region. In addition to its role in activation of the complement cascade, C1q has non-complement functions, regulating several aspects of DC function [64,65]. Although data from different studies are not entirely consistent, it is generally accepted that C1q-opsonized apoptotic cells downregulate DC production of cytokines. In one study, however, C1q was shown to increase IL-12 production by DCs when the cells were stimulated with LPS and apoptotic cells [66]. Some studies suggest that the anti-inflammatory function of C1q characterized as inhibition of IL-12 p40 and TNFα expression is due to decreased NFκB, p38, c-Jun and ERK activation [67,68]. Apoptotic cells opsonized with complement components can also inhibit IL-12 production directly through the negative regulation of transcription of IL-12 p35 [69]. Interestingly, apoptotic cells incubated with C1q-deficient serum lost their anti-inflammatory function, highlighting the key role of C1q in the suppressive function of apoptotic cells in DCs (Kim SJ and Ma, X personal observation). C1q and dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) engagement on DCs enhances the immunosuppressive function of DCs by increasing production of IL-10 [70]. Monocyte derived-DCs (MDDCs) differentiated with exogenous C1q show reduced IL-12 and IL-23 production, but elevated IL-10 production [71,72]. More recently, C1q was shown to indirectly inhibit regulatory function by sequestering immune complexes, thereby preventing type I IFN secretion from pDCs [73,74]. Moreover, C1q binds to leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1 (Lair-1; CD305) on monocytes which inhibits monocyte differentiation to MDDCs in vitro [75] and TLR-mediated production of type I IFNs. Thus C1q regulates immune homeostasis through preventing the differentiation of monocytes to DCs and through regulation of cytokine production by DCs (Fig. 2).

5. microRNA: a novel regulator of DC function

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs which negatively regulate specific target genes by mRNA degradation or translational repression [76]. MiRNAs are numerous and reside throughout the genome showing a range of spatial and temporal expression patterns. The importance of miRNA in DCs was investigated by studies of conditional deletion of miRNA. There was a minimal effect observed from DC specific (CD11c-driven) Dicer knockout mice which showed only a slight reduction in miRNA expression [77]. However, direct inhibition of specific miRNAs using miRNA inhibitors or by specific miRNA knockout have demonstrated functional specificity of different miRNAs in DCs (reviewed in [78]). The importance of understanding how miRNA expression affects DC function is enhanced by the finding that miRNA can be transferred between cells by exosomes and can affect gene expression in recipient cells [79,80].

5.1. Role of miRNA expression during DC development

Studies of miRNA expression patterns have identified several miRNAs that are regulated during DC differentiation (Table 2). In human MDDCs, the level of miR-21 and miR-34a is increased during differentiation, and their expression is required for the coordinated regulation of translation of Wnt-1 and Jagged-1 [81]. Treatment of monocytes with miR-21 and miR-34 inhibitors partially blocked MDDC differentiation, supporting a positive role for these miRNAs during MDDC differentiation. In mice, the miR-23a/24/27a cluster is more highly expressed in cDCs than pDCs and has been reported to inhibit lymphopoiesis and positively regulate myelopoiesis [82]. It is interesting that pDCs which bifurcate from cDCs during differentiation share a miRNA expression pattern with lymphocytes and lymphocyte progenitors rather than DC progenitors [83,84].

Table 2.

Summary of miRNAs involved in modulation of TLR signaling and DC function.

| miRNA | Verified targets | Mechanism in DCs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Let-7 family | TLR4, SOCS-1, IL-6 | Regulation of DC maturation and cytokine production | [51,92] |

| miR-142-3p | IL-6 | Inhibition of IL-6 production | [98] |

| miR-146 | IRAK1, IRAK2, TRAF6 | Negatively regulate TLR signaling | [90] |

| miR-148/152 | CaMKIIα | Inhibition of antigen presentation and cytokine production (IL-12, IL-6, TNFα, and IFNβ) | [149] |

| miR-155 | MyD88, TAB2, SHIP1, SOCS-1 | Alteration of DC maturation and cytokine profile | [85] |

| miR-155* | IRAKM | Positive regulation of type I IFN expression | [105,106] |

| miR-199 | IKKα | Enhanced NFκB signaling | [92] |

| miR-21 | IL-12 p35, PDCD4 | Altered cytokine production | [86,94] |

| miR-223 | TLR3, TLR4, IKKα | Alteration of TLR expression and TLR signaling | [88,89] |

| mR-579/221/125b | TNFα | Alteration of DC maturation and cytokine profile | [99] |

| miR-9 | NFκB | Negative feedback of NFκB activation | [93] |

5.2. Role of miRNA in DC maturation and function

Expression studies have shown that the level of several miRNAs is upregulated or downregulated after DC activation. Specific sets of miRNA target molecules are involved in various steps of DC activation; the TLR signaling pathway is the one that has been most extensively studied (Table 1). Although there are significant differences in miRNA expression profiles in different DC subsets, miR-21, miR-146 and miR-155 are ubiquitously increased upon TLR4 stimulation in DCs [85,86]. There is also evidence that certain miRNAs are downregulated upon TLR stimulation. In general, regulation of miRNA-mediated TLR activity is accomplished through targeting intracellular signaling molecules rather than targeting TLR itself. However, a few miRNAs can directly target TLRs; TLR4 RNA can be recognized by miR-223 and the let-7 family and TLR3 by miR-223 [87–89]. Although these data point to the regulation of certain TLRs by miRNAs, the limited data may underscore the importance of constitutive expression of TLRs in DCs.

MiR-146 has been shown to directly target IL-1R-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNFR-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) in human monocytes; miR-146 also negatively regulates the TLR-MyD88-NFκB pathway [90]. MyD88 and TAK1-binding protein 2 (TAB2), signaling molecules downstream of TRAF6 were confirmed as direct targets of miR-155 [85]. In addition to the proximal signaling molecules, molecules that are further downstream of TLR activation and effector molecules, such as cytokines or chemokines, are targets of miRNAs. The negative regulator of the NFκB pathway, IKKα, was recently shown to be a target of miR-223 in macrophages [91] and miR-199 in ovarian cancer cells [92]. More recently, miR-9 was shown to directly target NFκB1 which is cleaved to form the NFκB p50 subunit [93]. Several miRNAs can target cytokine and chemokine encoding mRNAs. Of note, miR-21 has a strong anti-inflammatory effect by targeting IL-12 p35 mRNA directly [94] and regulating IL-10 production through the binding of programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) [86], which functions as an inhibitor of translation by inhibiting eukaryotic translation-initiation factor 4F (EIF4F) [95,96]. IL-6 mRNA contains a target site for let-7c and miR-142–3p [97], [98]. The 3′ UTR of TNFα mRNA contains binding sites for miR-221, miR-579, and miR-125b [99,100]. In many studies, Src homology 2 (SH2) domain containing inisitol-5′-phosphatase 1 (SHIP1) has been shown to be a target of miR-155 and increased expression of miR-155 results in decreased expression of SHIP1 following LPS stimulation or pathogen infection [101–103]. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS-1) has been demonstrated to be targeted by miR-155 and let-7 family members in DCs; direct targeting was demonstrated by luciferase assays [51,104]. Differentially processed miRNA, miR-155 and miR-155*, show opposite roles in type I IFN production in human pDCs: negative regulation by miR-155 by targeting TAB2 and positive regulation by miR-155* by suppressing IRAKM, a negative regulator of TLR signaling which inhibits the dissociation of IRAK/IRAK4 from MyD88 [105,106]. Conversely, miRNA also can compete with RNA-binding proteins to protect mRNA from destabilization, demonstrated by increased stability of IL-10 mRNA in the presence of miR-4661 [107].

Together, these observations indicate that expression of miRNAs is another critical layer in regulating DC function at many different stages of maturation and activation. Most data on miRNA derive from a limited number of innate cell types (macrophages, splenic DCs, and MDDCs) or cancer cells. DCs are composed of numerous subsets in lymphoid organs and even more complicated subsets in non-lymphoid organs. Therefore, comprehensive studies of the expression profile of miRNAs and their role in different lymphoid and non-lymphoid resident DC subsets need to be performed to further understand their physiological role in DCs.

6. Human DCs

Until recently, most studies of human DC biology were performed with in vitro differentiated DCs, obtained either from peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes stimulated with GM-CSF and IL-4 (MDDCs) [108] or from cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors stimulated with GM-CSF and TNFα [109]. A major hurdle to the identification of genuine DCs in humans are the discordant phenotypic markers between mouse and human DCs. Increased refinement of flow cytometry approaches and gene expression profile studies have identified heterogeneous human DC subsets and even the counterparts of mouse DCs. Currently, four different populations of DCs in human are generally accepted to be present in blood (Table 3). All the DC subsets are negative for Lin markers (CD3, D19, CD14, CD20, CD56 and glycophorine A) and are HLA-DR positive; pDCs (CD11clowCD1a-CD123hiBDCA2+BDCA4+) [110], CD1c+ DCs (CD11c+CD1a-BDCA1+BDCA3+/−CD11blow) [111], BDCA3+ DCs (CD141+ DCs; CD11c+CD1a-BDCA1-BDCA3+ CD11blow) [112], and CD16+ DCs (Slan-DCs; CD11c+CD16+) [113]. Unlike CD1c+ DC and CD141+ DCs, CD16+ DCs are absent from tissues and are considered to represent a monocyte subset despite their name [114]. In addition to their specific surface markers, human DCs also have distinct sets of pattern recognition receptors, resembling their mouse DC counterparts.

Table 3.

Phenotype of human DCs.

| CD1c DC | BDCA3+ DC (CD141+) | pDC | CD16+ DC | MO-DC (CD14+)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Surface markers | CD11chi, HLA-DRhi, CD11b+, SIRPα+, BDCA1+ | CD11chi, HLA-DRhi, XCR1 CLEC9A+, BDCA3, CD1a−, BDCA1−, CD11blow, CD141+, Dec-205hi | CD11c−, HLA-DR+, CD123hi, BDCA2+, BDCA4+, CD1a− | CD11chi, HLA-DRhi, CD11b+, CD16+ | CD11chi,HLA-DRhi, CD1a−CD11b+, CD1a−, CD14+, BDCA1+, DC-SIGN+, CD163− |

| TLRs | TLR1+, TLR2+, TLR3+, TLR4+, TLR5+, TLR6+, TLR7−, TLR8+, TLR9−b | TLR1+, TLR2+, TLR3+, TLR4−, TLR5−, TLR6+, TLR7−, TLR8+, TLR9− | TLR1+, TLR2−, TLR3−, TLR4−, TLR5−, TLR6+, TLR7+, TLR8−, TLR9+ | TLR1+, TLR2+, TLR3−, TLR4+, TLR5+, TLR6+, TLR7+, TLR8, TLR9+ | TLR1−, TLR2+, TLR3−, TLR4+, TLR5+, TLR6−, TLR7−, TLR8−, TLR9+b |

| Transcription factors | IRF4 and Notch2 | BATF3 | E2-2 | ND | ND |

| Specific functions | Presentation of antigen and secrete IL-6 and IL-23 | Cross-presentation of antigen to activate CD8+ T cells and secrete high level of IL-12 | Presentation of antigen only after activation and secrete type 1 IFN | Secrete high level of TNFα and IL-12 | Present HLA-DR restricted antigen and secrete high level of TNFα and iNOS |

| Location | Blood and lymphoid tissue | Blood and lymphoid tissue | Blood and lymphoid tissue | Blood | Cutaneous tissue |

| Mouse DC counterpart | CD11b+ DC | CD103+ cDC CD8α+ cDCs | pDC | CD11chiMHCIIhi CX3CR1hi DC | ND |

BATF3, basic leucine zipper transcription factor ATF-like 3; BDCA, blood dendritic cell antigen; CLEC9A, C-type lectin domain family 9 member A; SIRPα, signal-regulatory protein-1; XCR1, the C sub-family chemokine receptor; ND, not determined.

CD14+ MO-DCs are observed only under inflammatory condition.

TLR measurement was performed by qPCR and not confirmed protein expression.

Two DC subsets, CD1c+ DC and CD141+ DCs are found in human spleens and tonsils, and correspond to mouse lymphoid tissue-resident DCs [115–117]. Gene chip analyses of the transcriptome of multiple subsets of mouse and human DCs have suggested that human CD141+ DCs are related to mouse CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs, whereas human CD1c+ DCs are related to mouse CD11b+ DCs [118]. Several studies have confirmed a functional resemblance between human CD141+ DCs and mouse CD8α+ DCs [115,117]. CD141+ DCs express Clec9A, high BATF3, IRF8 but not IRF4, TLR9, and CD11b. Moreover, they can cross-present cell-associated antigens to CD8α+ T cells. Blocking of BATF3 during in vitro culture inhibits CD141+ DCs but not CD1c+ DCs [119], again suggesting that they developmentally resemble mouse CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs. In contrast to mouse, an IRF8 mutation in two immunodeficient patients leads to either a complete absence of DCs and monocytes or a specific depletion of CD1c+ DCs but not CD141+ DCs [42].

7. DCs in autoimmune diseases

Since DCs are major regulators of fate-decisions of antigen-specific T cells and subsequent B cell activation, abnormal DC function can directly disrupt immune tolerance resulting in autoimmune disease. An initial question regarding DCs in autoimmunity was whether the actual size of the DC population contributes to the development of autoimmunity. An initial report of a constitutive ablation of cDCs in mice showed a myeloproliferative and autoimmune syndrome in a mixed genetic background [120], but normal development of T cells and no obvious autoimmune phenotypes in inbred strains [121]. Constitutive ablation of cDCs in mice with an autoimmune prone background ameliorated rather than exacerbated the disease [122]. Moreover, deletion of specific subsets of DCs, including CD8α+ cDCs and pDCs, did not cause any detectable autoimmunity [123,124]. Increases in the number of CD11chi cDCs and CD103+ DCs have been associated with Treg expansion resulting in a more tolerogenic environment [125,126]. Thus, the mere loss or gain of DC number seems not to directly cause autoimmunity.

Studies of mice with DC-specific targeting of single genes have uncovered the effects of particular genes in DCs on autoimmunity and have demonstrated that changes in DC functionality might induce inflammation and/or autoimmune manifestations (Table 1). It should be noted that most of the genes studied so far are negative regulators of pro-inflammatory signals (T-bet, Foxo3 and Blimp1) or molecules that are upstream or downstream of inflammatory signals (Stat3, Nfκb and Irfs). They are general regulators of immune function and alterations in their expression in other cell types also cause inflammation and/or autoimmunity. However, studies of BLIMP-1 show that it has a cell-type dependent regulatory function; gain-of-function in B cells and loss-of-function in DCs and T cells are both correlated with autoimmunity. Therefore, DC-specific regulators that prevent DC hyperactivation and autoimmunity remain mostly unknown and need to be identified.

7.1. DC-mediated modification of T cells in autoimmunity

As discussed above, DCs can affect T helper (TH) cell differentiation and TH cell function by producing various combinations of pro- and/or anti-inflammatory cytokines thereby affecting the development of autoimmunity. Several, but not all, studies have shown that systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients have a reduced number of circulating Treg cells [127–129]. Moreover, there is an inverse correlation between the number of Treg cells and SLE disease activity [130] and the level of autoantibodies [131]. TGFβ is a critical cytokine for Treg differentiation, and a strong association of a genetic variant of TGFβ with SLE has been identified [132]. TGFβ is expressed in many cells including DCs and its expression in DCs is, indeed, regulated by apoptotic cells and pathogens, among other factors. Over production of IL-6 from DCs has been shown to inhibit Treg regulatory function in the B6.Sle1.Sle2.Sle3 triple congenic mouse model of SLE [133], supporting the role of DCs as key regulators in Treg differentiation and function.

After follicular helper T cells (TFH) were identified, their functional involvement in autoimmunity was investigated. TFH cells directly interact with B cells in germinal centers (GCs) and provide support for B cell differentiation to antibody producing plasma cells [134]. TFH cell differentiation is determined by expression of the master transcription factor, Bcl-6, and the cytokines IL-6 and IL-21 [135,136]. DCs have been known to be key players in the initial stage of TFH cell differentiation by providing cytokines and an ICOS/ICOS-ligand interaction to naïve T cells [137]. An increase in the number of TFH cells is associated with an autoimmune syndrome in genetically modified mice [138] and there is evidence of increased circulating TFH-like cells in SLE patients [139]. Mice with a DC-specific ablation of Blimp-1 are of particular interest. Blimp-1 deficient DCs were shown to induce TFH cell differentiation preferentially through increased IL-6 production, enhancing GC reactions and leading to the activation of autoreactive B cells [140]. Strikingly, the resulting phenotype occurs predominantly in female animals, which recapitulates the strong female bias of SLE. Polymorphisms in the PRDM1 gene have been associated with SLE in humans [141,142], consistent with its function as a DC regulator. Thus, these studies underscore the need for tight regulation of TFH cell differentiation and demonstrate that aberrant activation of DCs can be directly involved in autoimmunity.

8. Conclusions and future directions

Understanding the homeostatic signals that control DC function and maturation demonstrates how altered DC maturation or altered DC cytokine expression are involved in disease development. It is now clear that there is an extraordinarily complex network of cDCs, and their functional properties are regulated by the environment, causing them to diverge into tolerogenic DCs or immunogenic DCs. The immunological contribution of cDCs depends on their location. A large number of molecules regulating DCs have been discovered and their contributions to DC function have been proven by genetic modification in animal models. However, most of the biological functions of putative regulators need to be confirmed in more refined models. A challenge in this field is how to translate phenotypes in animals to complex human diseases. Recent advances in human DC biology achieved by the identification of specific surface molecules enable researchers to confirm their role in the human system. Together with the advance in human DC biology, fine mapping and functional evidence of each (or multiple) contributors need to be achieved.

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Davidson and Y.R. Zou for valuable discussion and comments on this manuscript. S.J.K. has been supported by National Institutes of Health grant K01AR059378; and B.D. has been supported by The Alliance for Lupus Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Hoeffel G, Wang Y, Greter M, See P, Teo P, Malleret B, et al. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J Exp Med 2012;209:1167–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Fogg DK, Sibon C, Miled C, Jung S, Aucouturier P, Littman DR, et al. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science 2006;311:83–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Helft J, Shang L, Hashimoto D, Greter M, et al. Origin of the lamina propria dendritic cell network. Immunity 2009;31:513–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ginhoux F, Liu K, Helft J, Bogunovic M, Greter M, Hashimoto D, et al. The origin and development of nonlymphoid tissue CD103+ DCs. J Exp Med 2009;206:3115–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, et al. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity 2009;31:502–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, et al. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science 2009;324:392–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Naik SH, Metcalf D, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Wicks I, Wu L, O’Keeffe M, et al. Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes. Nat Immunol 2006;7:663–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Naik S, Vremec D, Wu L, O’Keeffe M, Shortman K. CD8alpha+ mouse spleen dendritic cells do not originate from the CD8alpha− dendritic cell subset. Blood 2003;102:601–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kabashima K, Banks TA, Ansel KM, Lu TT, Ware CF, Cyster JG. Intrinsic lymphotoxin-beta receptor requirement for homeostasis of lymphoid tissue dendritic cells. Immunity 2005;22:439–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liu K, Waskow C, Liu X, Yao K, Hoh J, Nussenzweig M. Origin of dendritic cells in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. Nat Immunol 2007;8:578–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Manz MG, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Dendritic cell potentials of early lymphoid and myeloid progenitors. Blood 2001;97:3333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Traver D, Akashi K, Manz M, Merad M, Miyamoto T, Engleman EG, et al. Development of CD8alpha-positive dendritic cells from a common myeloid progenitor. Science 2000;290:2152–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Serbina NV, Salazar-Mather TP, Biron CA, Kuziel WA, Pamer EG. TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells mediate innate immune defense against bacterial infection. Immunity 2003;19:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Satpathy AT, Kc W, Albring JC, Edelson BT, Kretzer NM, Bhattacharya D, et al. Zbtb46 expression distinguishes classical dendritic cells and their committed progenitors from other immune lineages. J Exp Med 2012;209:1135–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Meredith MM, Liu K, Darrasse-Jeze G, Kamphorst AO, Schreiber HA, Guermonprez P, et al. Expression of the zinc finger transcription factor zDC (Zbtb46, Btbd4) defines the classical dendritic cell lineage. J Exp Med 2012;209:1153–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].De Trez C, Magez S, Akira S, Ryffel B, Carlier Y, Muraille E. iNOS-producing inflammatory dendritic cells constitute the major infected cell type during the chronic Leishmania major infection phase of C57BL/6 resistant mice. PLoS Pathog 2009;5:e1000494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Copin R, De Baetselier P, Carlier Y, Letesson JJ, Muraille E. MyD88-dependent activation of B220-CD11b+LY-6C+ dendritic cells during Brucella melitensis infection. J Immunol 2007;178:5182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Guilliams M, Movahedi K, Bosschaerts T, VandenDriessche T, Chuah MK, Herin M, et al. IL-10 dampens TNF/inducible nitric oxide synthase-producing dendritic cell-mediated pathogenicity during parasitic infection. J Immunol 2009;182:1107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Randolph GJ, Inaba K, Robbiani DF, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity 1999;11:753–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 2003;19:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cheong C, Matos I, Choi JH, Dandamudi DB, Shrestha E, Longhi MP, et al. Microbial stimulation fully differentiates monocytes to DC-SIGN/CD209(+) dendritic cells for immune T cell areas. Cell 2010;143:416–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Segura E, Albiston AL, Wicks IP, Chai SY, Villadangos JA. Different cross-presentation pathways in steady-state and inflammatory dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nakano H, Lin KL, Yanagita M, Charbonneau C, Cook DN, Kakiuchi T, et al. Blood-derived inflammatory dendritic cells in lymph nodes stimulate acute T helper type 1 immune responses. Nat Immunol 2009;10:394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fei M, Bhatia S, Oriss TB, Yarlagadda M, Khare A, Akira S, et al. TNF-alpha from inflammatory dendritic cells (DCs) regulates lung IL-17A/IL-5 levels and neutrophilia versus eosinophilia during persistent fungal infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011;108:5360–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Laufer TM, DeKoning J, Markowitz JS, Lo D, Glimcher LH. Unopposed positive selection and autoreactivity in mice expressing class II MHC only on thymic cortex. Nature 1996;383:81–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Barclay AN, Mayrhofer G. Bone marrow origin of Ia-positive cells in the medulla rat thymus. J Exp Med 1981;153:1666–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Belz GT, Behrens GM, Smith CM, Miller JF, Jones C, Lejon K, et al. The CD8alpha(+) dendritic cell is responsible for inducing peripheral self-tolerance to tissue-associated antigens. J Exp Med 2002;196:1099–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med 2007;204:1757–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Maldonado RA, von Andrian UH. How tolerogenic dendritic cells induce regulatory T cells. Adv Immunol 2010;108:111–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mason D, Powrie F. Control of immune pathology by regulatory T cells. Curr Opin Immunol 1998;10:649–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Schuler G, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of interleukin 10-producing, nonproliferating CD4(+) T cells with regulatory properties by repetitive stimulation with allogeneic immature human dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2000;192:1213–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, Parcellier A, Schmitt E, Solary E, et al. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-beta-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med 2005;202:919–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Li X, Yang A, Huang H, Zhang X, Town J, Davis B, et al. Induction of type 2T helper cell allergen tolerance by IL-10-differentiated regulatory dendritic cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010;42:190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fujita S, Sato Y, Sato K, Eizumi K, Fukaya T, Kubo M, et al. Regulatory dendritic cells protect against cutaneous chronic graft-versus-host disease mediated through CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood 2007;110:3793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Puccetti P, Grohmann U. IDO and regulatory T cells: a role for reverse signalling and non-canonical NF-kappaB activation. Nat Rev Immunol 2007;7:817–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Swiecki M, Colonna M. Unraveling the functions of plasmacytoid dendritic cells during viral infections, autoimmunity, and tolerance. Immunol Rev 2010;234:142–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Grohmann U, Volpi C, Fallarino F, Bozza S, Bianchi R, Vacca C, et al. Reverse signaling through GITR ligand enables dexamethasone to activate IDO in allergy. Nat Med 2007;13:579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Guilliams M, Crozat K, Henri S, Tamoutounour S, Grenot P, Devilard E, et al. Skin-draining lymph nodes contain dermis-derived CD103(−) dendritic cells that constitutively produce retinoic acid and induce Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells. Blood 2010;115:1958–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Belladonna ML, Volpi C, Bianchi R, Vacca C, Orabona C, Pallotta MT, et al. Cutting edge: autocrine TGF-beta sustains default tolerogenesis by IDO-competent dendritic cells. J Immunol 2008;181:5194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Matteoli G, Mazzini E, Iliev ID, Mileti E, Fallarino F, Puccetti P, et al. Gut CD103+ dendritic cells express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase which influences T regulatory/T effector cell balance and oral tolerance induction. Gut 2010;59:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Becker AM, Michael DG, Satpathy AT, Sciammas R, Singh H, Bhattacharya D. IRF-8 extinguishes neutrophil production and promotes dendritic cell lineage commitment in both myeloid and lymphoid mouse progenitors. Blood 2012;119:2003–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hambleton S, Salem S, Bustamante J, Bigley V, Boisson-Dupuis S, Azevedo J, et al. IRF8 mutations and human dendritic-cell immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med 2011;365:127–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Sestili P, Borghi P, Venditti M, Morse HC 3rd, et al. ICSBP is essential for the development of mouse type I interferon-producing cells and for the generation and activation of CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2002;196:1415–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Orabona C, Puccetti P, Vacca C, Bicciato S, Luchini A, Fallarino F, et al. Toward the identification of a tolerogenic signature in IDO-competent dendritic cells. Blood 2006;107:2846–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rathinam C, Geffers R, Yucel R, Buer J, Welte K, Moroy T, et al. The transcriptional repressor Gfi1 controls STAT3-dependent dendritic cell development and function. Immunity 2005;22:717–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Melillo JA, Song L, Bhagat G, Blazquez AB, Plumlee CR, Lee C, et al. Dendritic cell (DC)-specific targeting reveals Stat3 as a negative regulator of DC function. J Immunol 2010;184:2638–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Faveeuw C, Fougeray S, Angeli V, Fontaine J, Chinetti G, Gosset P, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators inhibit interleukin-12 production in murine dendritic cells. FEBS Lett 2000;486:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nencioni A, Grunebach F, Zobywlaski A, Denzlinger C, Brugger W, Brossart P. Dendritic cell immunogenicity is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Immunol 2002;169:1228–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chan YH, Chiang MF, Tsai YC, Su ST, Chen MH, Hou MS, et al. Absence of the transcriptional repressor Blimp-1 in hematopoietic lineages reveals its role in dendritic cell homeostatic development and function. J Immunol 2009;183:7039–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Smith MA, Wright G, Wu J, Tailor P, Ozato K, Chen X, et al. Positive regulatory domain I (PRDM1) and IRF8/PU.1 counter-regulate MHC class II transactivator (CIITA) expression during dendritic cell maturation. J Biol Chem 2011;286:7893–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kim SJ, Gregersen PK, Diamond B. Regulation of dendritic cell activation by microRNA let-7c and BLIMP1. J Clin Invest 2013;123:823–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kim SJ, Zou YR, Goldstein J, Reizis B, Diamond B. Tolerogenic function of Blimp-1 in dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2011;208:2193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ohtsuka H, Sakamoto A, Pan J, Inage S, Horigome S, Ichii H, et al. Bcl6 is required for the development of mouse CD4+ and CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Immunol 2011;186:255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Greter M, Helft J, Chow A, Hashimoto D, Mortha A, Agudo-Cantero J, et al. GM-CSF controls nonlymphoid tissue dendritic cell homeostasis but is dispensable for the differentiation of inflammatory dendritic cells. Immunity 2012;36:1031–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhan Y, Carrington EM, van Nieuwenhuijze A, Bedoui S, Seah S, Xu Y, et al. GM-CSF increases cross-presentation and CD103 expression by mouse CD8(+) spleen dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 2011;41:2585–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Park SJ, Nakagawa T, Kitamura H, Atsumi T, Kamon H, Sawa S, et al. IL-6 regulates in vivo dendritic cell differentiation through STAT3 activation. J Immunol 2004;173:3844–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hegde S, Pahne J, Smola-Hess S. Novel immunosuppressive properties of interleukin-6 in dendritic cells: inhibition of NF-kappaB binding activity and CCR7 expression. FASEB J 2004;18:1439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rovere-Querini P, Capobianco A, Scaffidi P, Valentinis B, Catalanotti F, Giazzon M, et al. HMGB1 is an endogenous immune adjuvant released by necrotic cells. EMBO Rep 2004;5:825–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dumitriu IE, Baruah P, Bianchi ME, Manfredi AA, Rovere-Querini P. Requirement of HMGB1 and RAGE for the maturation of human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 2005;35:2184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Messmer D, Yang H, Telusma G, Knoll F, Li J, Messmer B, et al. High mobility group box protein 1: an endogenous signal for dendritic cell maturation and Th1 polarization. J Immunol 2004;173:307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Yang H, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Palmblad K, Wang H, Ochani M, Li J, et al. A critical cysteine is required for HMGB1 binding to Toll-like receptor 4 and activation of macrophage cytokine release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:11942–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ma Y, Adjemian S, Mattarollo SR, Yamazaki T, Aymeric L, Yang H, et al. Anti-cancer chemotherapy-induced intratumoral recruitment and differentiation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity 2013;38:729–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bianchi ME, Manfredi AA. High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) protein at the crossroads between innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev 2007;220:35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Elkon KB, Santer DM. Complement, interferon and lupus. Curr Opin Immunol 2012;24:665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lu JH, Teh BK, Wang L, Wang YN, Tan YS, Lai MC, et al. The classical and regulatory functions of C1q in immunity and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol 2008;5:9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Baruah P, Dumitriu IE, Peri G, Russo V, Mantovani A, Manfredi AA, et al. The tissue pentraxin PTX3 limits C1q-mediated complement activation and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol 2006;80:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Waggoner SN, Cruise MW, Kassel R, Hahn YS. gC1q receptor ligation selectively down-regulates human IL-12 production through activation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. J Immunol 2005;175:4706–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Yamada M, Oritani K, Kaisho T, Ishikawa J, Yoshida H, Takahashi I, et al. Complement C1q regulates LPS-induced cytokine production in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 2004;34:221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kim S, Elkon KB, Ma X. Transcriptional suppression of interleukin-12 gene expression following phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Immunity 2004;21:643–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Hosszu KK, Valentino A, Vinayagasundaram U, Vinayagasundaram R, Joyce MG, Ji Y, et al. DC-SIGN, C1q, and gC1qR form a trimolecular receptor complex on the surface of monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells. Blood 2012;120:1228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Teh BK, Yeo JG, Chern LM, Lu J. C1q regulation of dendritic cell development from monocytes with distinct cytokine production and T cell stimulation. Mol Immunol 2011;48:1128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Castellano G, Woltman AM, Schlagwein N, Xu W, Schena FP, Daha MR, et al. Immune modulation of human dendritic cells by complement. Eur J Immunol 2007;37:2803–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Santer DM, Hall BE, George TC, Tangsombatvisit S, Liu CL, Arkwright PD, et al. C1q deficiency leads to the defective suppression of IFN-alpha in response to nucleoprotein containing immune complexes. J Immunol 2010;185:4738–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lood C, Gullstrand B, Truedsson L, Olin AI, Alm GV, Ronnblom L, et al. C1q inhibits immune complex-induced interferon-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells: a novel link between C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3081–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Son M, Santiago-Schwarz F, Al-Abed Y, Diamond B. C1q limits dendritic cell differentiation and activation by engaging LAIR-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:E3160–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004;116:281–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Kuipers H, Schnorfeil FM, Fehling HJ, Bartels H, Brocker T. Dicer-dependent microRNAs control maturation, function, and maintenance of Langerhans cells in vivo. J Immunol 2010;185:400–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Turner ML, Schnorfeil FM, Brocker T. MicroRNAs regulate dendritic cell differentiation and function. J Immunol 2011;187:3911–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Hunter MP, Ismail N, Zhang X, Aguda BD, Lee EJ, Yu L, et al. Detection of microRNA expression in human peripheral blood microvesicles. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan ML, Karlsson JM, et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood 2012;119:756–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Hashimi ST, Fulcher JA, Chang MH, Gov L, Wang S, Lee B. MicroRNA profiling identifies miR-34a and miR-21 and their target genes JAG1 and WNT1 in the coordinate regulation of dendritic cell differentiation. Blood 2009;114:404–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kong KY, Owens KS, Rogers JH, Mullenix J, Velu CS, Grimes HL, et al. MIR-23A microRNA cluster inhibits B-cell development. Exp Hematol 2010;38:629–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Kuipers H, Schnorfeil FM, Brocker T. Differentially expressed microRNAs regulate plasmacytoid vs. conventional dendritic cell development. Mol Immunol 2010;48:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Xiao C, Srinivasan L, Calado DP, Patterson HC, Zhang B, Wang J, et al. Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17–92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 2008;9:405–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Ceppi M, Pereira PM, Dunand-Sauthier I, Barras E, Reith W, Santos MA, et al. MicroRNA-155 modulates the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:2735–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, Martin C, O’Leary JJ, Ruan Q, et al. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol 2010;11:141–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 2004;303:83–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Androulidaki A, Iliopoulos D, Arranz A, Doxaki C, Schworer S, Zacharioudaki V, et al. The kinase Akt1 controls macrophage response to lipopolysaccharide by regulating microRNAs. Immunity 2009;31:220–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Chen XM, Splinter PL, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF. A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J Biol Chem 2007;282:28929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:12481–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Li T, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Zhang Y, Kim YS, Liu ZG. MicroRNAs modulate the noncanonical transcription factor NF-kappaB pathway by regulating expression of the kinase IKKalpha during macrophage differentiation. Nat Immunol 2010;11:799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Chen R, Alvero AB, Silasi DA, Kelly MG, Fest S, Visintin I, et al. Regulation of IKKbeta by miR-199a affects NF-kappaB activity in ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene 2008;27:4712–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Bazzoni F, Rossato M, Fabbri M, Gaudiosi D, Mirolo M, Mori L, et al. Induction and regulatory function of miR-9 in human monocytes and neutrophils exposed to proinflammatory signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:5282–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Lu TX, Munitz A, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA-21 is up-regulated in allergic airway inflammation and regulates IL-12p35 expression. J Immunol 2009;182:4994–5002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Yang HS, Jansen AP, Komar AA, Zheng X, Merrick WC, Costes S, et al. The transformation suppressor Pdcd4 is a novel eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A binding protein that inhibits translation. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Loh PG, Yang HS, Walsh MA, Wang Q, Wang X, Cheng Z, et al. Structural basis for translational inhibition by the tumour suppressor Pdcd4. EMBO J 2009;28:274–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. An epigenetic switch involving NF-kappaB, Lin28, Let-7 MicroRNA, and IL6 links inflammation to cell transformation. Cell 2009;139:693–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Sun Y, Varambally S, Maher CA, Cao Q, Chockley P, Toubai T, et al. Targeting of microRNA-142–3p in dendritic cells regulates endotoxin-induced mortality. Blood 2011;117:6172–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, Costinean S, Dumitru CD, Adair B, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol 2007;179:5082–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].El Gazzar M, McCall CE. MicroRNAs distinguish translational from transcriptional silencing during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem 2010;285:20940–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].McCoy CE, Sheedy FJ, Qualls JE, Doyle SL, Quinn SR, Murray PJ, et al. IL-10 inhibits miR-155 induction by Toll-like receptors. J Biol Chem 2010;285:20492–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].O’Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:7113–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Cremer TJ, Ravneberg DH, Clay CD, Piper-Hunter MG, Marsh CB, Elton TS, et al. MiR-155 induction by F. novicida but not the virulent F. tularensis results in SHIP down-regulation and enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokine response. PLoS ONE 2009;4:e8508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Wang P, Hou J, Lin L, Wang C, Liu X, Li D, et al. Inducible microRNA-155 feedback promotes type I IFN signaling in antiviral innate immunity by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. J Immunol 2010;185:6226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Zhou H, Huang X, Cui H, Luo X, Tang Y, Chen S, et al. miR-155 and its starform partner miR-155* cooperatively regulate type I interferon production by human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood 2010;116:5885–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Kobayashi K, Hernandez LD, Galan JE, Janeway CA Jr, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell 2002;110:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ma F, Liu X, Li D, Wang P, Li N, Lu L, et al. MicroRNA-466l upregulates IL-10 expression in TLR-triggered macrophages by antagonizing RNA-binding protein tristetraprolin-mediated IL-10 mRNA degradation. J Immunol 2010;184:6053–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med 1994;179:1109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. GM-CSF and TNF-alpha cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature 1992;360:258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Reizis B, Bunin A, Ghosh HS, Lewis KL, Sisirak V. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: recent progress and open questions. Annu Rev Immunol 2011;29:163–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Ito T, Inaba M, Inaba K, Toki J, Sogo S, Iguchi T, et al. A CD1a+/CD11c+ subset of human blood dendritic cells is a direct precursor of Langerhans cells. J Immunol 1999;163:1409–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Dzionek A, Fuchs A, Schmidt P, Cremer S, Zysk M, Miltenyi S, et al. BDCA-2, BDCA-3, and BDCA-4: three markers for distinct subsets of dendritic cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol 2000;165:6037–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Lindstedt M, Lundberg K, Borrebaeck CA. Gene family clustering identifies functionally associated subsets of human in vivo blood and tonsillar dendritic cells. J Immunol 2005;175:4839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Liebman RM, Schakel K. The CD16(+) (FcgammaRIII(+)) subset of human monocytes preferentially becomes migratory dendritic cells in a model tissue setting. J Exp Med 2002;196:517–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Poulin LF, Salio M, Griessinger E, Anjos-Afonso F, Craciun L, Chen JL, et al. Characterization of human DNGR-1+ BDCA3+ leukocytes as putative equivalents of mouse CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2010;207:1261–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].McIlroy D, Troadec C, Grassi F, Samri A, Barrou B, Autran B, et al. Investigation of human spleen dendritic cell phenotype and distribution reveals evidence of in vivo activation in a subset of organ donors. Blood 2001;97:3470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Jongbloed SL, Kassianos AJ, McDonald KJ, Clark GJ, Ju X, Angel CE, et al. Human CD141+ (BDCA-3)+ dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. J Exp Med 2010;207:1247–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Robbins SH, Walzer T, Dembele D, Thibault C, Defays A, Bessou G, et al. Novel insights into the relationships between dendritic cell subsets in human and mouse revealed by genome-wide expression profiling. Genome Biol 2008;9:R17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Poulin LF, Reyal Y, Uronen-Hansson H, Schraml BU, Sancho D, Murphy KM, et al. DNGR-1 is a specific and universal marker of mouse and human Batf3-dependent dendritic cells in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues. Blood 2012;119:6052–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Ohnmacht C, Pullner A, King SB, Drexler I, Meier S, Brocker T, et al. Constitutive ablation of dendritic cells breaks self-tolerance of CD4 T cells and results in spontaneous fatal autoimmunity. J Exp Med 2009;206:549–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Birnberg T, Bar-On L, Sapoznikov A, Caton ML, Cervantes-Barragan L, Makia D, et al. Lack of conventional dendritic cells is compatible with normal development and T cell homeostasis, but causes myeloid proliferative syndrome. Immunity 2008;29:986–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Teichmann LL, Ols ML, Kashgarian M, Reizis B, Kaplan DH, Shlomchik MJ. Dendritic cells in lupus are not required for activation of T and B cells but promote their expansion, resulting in tissue damage. Immunity 2010;33:967–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Edelson BT, Kc W, Juang R, Kohyama M, Benoit LA, Klekotka PA, et al. Peripheral CD103+ dendritic cells form a unified subset developmentally related to CD8alpha+ conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2010;207:823–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Cervantes-Barragan L, Lewis KL, Firner S, Thiel V, Hugues S, Reith W, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control T-cell response to chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:3012–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Darrasse-Jeze G, Deroubaix S, Mouquet H, Victora GD, Eisenreich T, Yao KH, et al. Feedback control of regulatory T cell homeostasis by dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med 2009;206:1853–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Collins CB, Aherne CM, McNamee EN, Lebsack MD, Eltzschig H, Jedlicka P, et al. Flt3 ligand expands CD103(+) dendritic cells and FoxP3(+) T regulatory cells, and attenuates Crohn’s-like murine ileitis. Gut 2012;61:1154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Lyssuk EY, Torgashina AV, Soloviev SK, Nassonov EL, Bykovskaia SN. Reduced number and function of CD4+CD25highFoxP3+ regulatory T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Adv Exp Med Biol 2007;601:113–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Franz B, Fritzsching B, Riehl A, Oberle N, Klemke CD, Sykora J, et al. Low number of regulatory T cells in skin lesions of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:1910–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Miyara M, Amoura Z, Parizot C, Badoual C, Dorgham K, Trad S, et al. Global natural regulatory T cell depletion in active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2005;175:8392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Valencia X, Yarboro C, Illei G, Lipsky PE. Deficient CD4+CD25high T regulatory cell function in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2007;178:2579–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Lee JH, Wang LC, Lin YT, Yang YH, Lin DT, Chiang BL. Inverse correlation between CD4+ regulatory T-cell population and autoantibody levels in paediatric patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology 2006;117:280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Barreto M, Ferreira RC, Lourenco L, Moraes-Fontes MF, Santos E, Alves M, et al. Low frequency of CD4+CD25+ Treg in SLE patients: a heritable trait associated with CTLA4 and TGFbeta gene variants. BMC Immunol 2009;10:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Wan S, Xia C, Morel L. IL-6 produced by dendritic cells from lupus-prone mice inhibits CD4+CD25+ T cell regulatory functions. J Immunol 2007;178:271–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, Ellwart J, Sallusto F, Lipp M, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med 2000;192:1545–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity 2008;29:138–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Dienz O, Eaton SM, Bond JP, Neveu W, Moquin D, Noubade R, et al. The induction of antibody production by IL-6 is indirectly mediated by IL-21 produced by CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med 2009;206:69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Choi YS, Kageyama R, Eto D, Escobar TC, Johnston RJ, Monticelli L, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity 2011;34:932–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Linterman MA, Rigby RJ, Wong RK, Yu D, Brink R, Cannons JL, et al. Follicular helper T cells are required for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med 2009;206:561–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Simpson N, Gatenby PA, Wilson A, Malik S, Fulcher DA, Tangye SG, et al. Expansion of circulating T cells resembling follicular helper T cells is a fixed phenotype that identifies a subset of severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:234–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Kim SJ, Caton M, Wang C, Khalil M, Zhou ZJ, Hardin J, et al. Increased IL-12 inhibits B cells’ differentiation to germinal center cells and promotes differentiation to short-lived plasmablasts. J Exp Med 2008;205:2437–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet 2009;41:1228–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Zhou XJ, Lu XL, Lv JC, Yang HZ, Qin LX, Zhao MH, et al. Genetic association of PRDM1-ATG5 intergenic region and autophagy with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese population. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1330–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Garrett WS, Lord GM, Punit S, Lugo-Villarino G, Mazmanian SK, Ito S, et al. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell 2007;131:33–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Dejean AS, Beisner DR, Ch’en IL, Kerdiles YM, Babour A, Arden KC, et al. Transcription factor Foxo3 controls the magnitude of T cell immune responses by modulating the function of dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 2009;10:504–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Dissanayake D, Hall H, Berg-Brown N, Elford AR, Hamilton SR, Murakami K, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB1 controls the functional maturation of dendritic cells and prevents the activation of autoreactive T cells. Nat Med 2011;17:1663–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Zanetti M, Castiglioni P, Schoenberger S, Gerloni M. The role of relB in regulating the adaptive immune response. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;987:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Negishi H, Fujita Y, Yanai H, Sakaguchi S, Ouyang X, Shinohara M, et al. Evidence for licensing of IFN-gamma-induced IFN regulatory factor 1 transcription factor by MyD88 in Toll-like receptor-dependent gene induction program. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006;103:15136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Owens BM, Moore JW, Kaye PM. IRF7 regulates TLR2-mediated activation of splenic CD11c(hi) dendritic cells. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e41050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Liu X, Zhan Z, Xu L, Ma F, Li D, Guo Z, et al. MicroRNA-148/152 impair innate response and antigen presentation of TLR-triggered dendritic cells by targeting CaMKIIalpha. J Immunol 2010;185:7244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]