Abstract

The ability of the gram-positive, food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes to tolerate environments of elevated osmolarity and reduced temperature is due in part to the transport and accumulation of the osmolyte glycine betaine. Previously we showed that glycine betaine transport was the result of Na+-glycine betaine symport. In this report, we identify a second glycine betaine transporter from L. monocytogenes which is osmotically activated but does not require a high concentration of Na+ for activity. By using a pool of Tn917-LTV3 mutants, a salt- and chill-sensitive mutant which was also found to be impaired in its ability to transport glycine betaine was isolated. DNA sequence analysis of the region flanking the site of transposon insertion revealed three open reading frames homologous to opuA from Bacillus subtilis and proU from Escherichia coli, both of which encode glycine betaine transport systems that belong to the superfamily of ATP-dependent transporters. The three open reading frames are closely spaced, suggesting that they are arranged in an operon. Moreover, a region upstream from the first reading frame was found to be homologous to the promoter regions of both opuA and proU. One unusual feature not shared with these other two systems is that the start codons for two of the open reading frames in L. monocytogenes appear to be TTG. That glycine betaine uptake is nearly eliminated in the mutant strain when it is assayed in the absence of Na+ is an indication that only the ATP-dependent transporter and the Na+-glycine betaine symporter occur in L. monocytogenes.

The gram-positive, food-borne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes is able to tolerate environmental stresses, such as reduced water activity and temperature extremes (5, 6, 16, 45). This high degree of adaptability is one reason that the pathogen can be difficult to control in a number of foods, since treatments used in food processing and preservation utilize the very environmental stresses to which L. monocytogenes shows resistance. Hence, the focus of research in a number of laboratories is the molecular mechanism by which L. monocytogenes adapts to environmental stresses. One area in particular that has received considerable attention is the mechanism of adaptation to osmotic stress. It has been shown that L. monocytogenes responds to elevated osmolarity in the environment by the intracellular accumulation of compatible solutes, called osmolytes. These osmolytes function in the cytosol by counterbalancing the external osmolarity without adversely affecting macromolecular structure or function (7, 47). Glycine betaine and carnitine, which are highly effective osmolytes in certain bacteria (7), were also found to protect L. monocytogenes against osmotic stress (3, 21, 39). However, these osmolytes were found to play the additional role of chill stress protectant in L. monocytogenes, a function which thus far is known to occur only in this pathogen (21).

The accumulation of glycine betaine and carnitine is achieved by osmotically activated and chill-activated transport from the medium rather than by de novo synthesis by the cell (21, 31, 39). Recent research on the characterization of these transport systems has shown that carnitine is accumulated via an ATP-dependent transport system (44), while glycine betaine uptake proceeds by symport with Na+ (11). This absolute requirement for Na+ was detected in vesicles; it was not observed in whole cells (20). In addition, the Na+-coupled transport system in vesicles showed classical Arrhenius behavior with temperature and did not appear to be activated by cold (11). These observations suggested that more than one transport system is responsible for stress-activated glycine betaine accumulation in L. monocytogenes.

In this article, we describe the isolation of a glycine betaine transport mutant of L. monocytogenes from a Tn917-LTV3 transposon insertional library and report the nucleotide sequences of genes encoding a glycine betaine transport system distinct from that described by Gerhardt et al. (11).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

L. monocytogenes strains used in this work were the wild-type isolate 10403S (41) and its derivatives, DP-L1044 (hly::Tn917-LTV3) (41) and LTG59 (this work). L. monocytogenes cultures were maintained on solid trypticase soy agar medium at 4°C, and brain heart infusion (BHI) (Difco) broth was used as rich medium. Luria-Bertani broth (37) was used to maintain Escherichia coli strains. When defined medium was required, the medium described by Pine and coworkers (33, 34) containing 0.5% glucose but lacking choline (modified Pine’s medium) was used. M63 (30) was used as the defined medium for E. coli WG439 (putP proP proU) (8). [Methyl-14C]glycine betaine was prepared by the oxidation of [methyl-14C]choline (NEN Research Products) (32). Kanamycin (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (50 μg/ml), and chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) were used as appropriate.

Measurements of growth rate and glycine betaine transport.

Growth rates of bacterial cultures were determined by turbidimetry as previously described (21). Experimental treatments were carried out at least in duplicate. Except where noted, glycine betaine transport rates were determined in duplicate by using [methyl-14C]glycine betaine as described previously (21). In experiments designed to determine the monovalent cation requirement, cultures were grown in K+-deficient modified Pine’s medium with 4% NaCl or in Na+-deficient modified Pine’s medium supplemented with 4% KCl. Cultures were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended to 1/10 of their original volumes in ACES (N-[2-acetamido]-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid) buffer (pH 6.75) containing the same concentration of chloride salt as the growth medium. Transport assays were initiated by the addition of 100 μM [14C]glycine betaine, and protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (27).

Isolation of glycine betaine transport-deficient mutants.

Glycine betaine transport-deficient mutants were isolated from a pool of transposon insertional mutants of L. monocytogenes 10403S containing Tn917-LTV3 (4) (provided by B. Walsh, University of California, Davis). This transposon confers resistance to chloramphenicol and kanamycin in L. monocytogenes and contains a promoterless lacZ gene, polylinker cloning sites, and ColE1 replication functions which allow direct cloning of the L. monocytogenes chromosomal DNA adjacent to the proximal side of lacZ (4). The pool was subjected to three rounds of penicillin enrichment in BHI medium containing 8% NaCl and 1 μg of penicillin per ml. Mutants were initially screened for growth on solid modified Pine’s medium, for resistance to chloramphenicol, and for the inability to be rescued by 100 μM glycine betaine when stressed by 8% NaCl. Putative transport mutants were subsequently analyzed for growth in liquid medium in the presence and absence of added NaCl and glycine betaine and for the uptake of [14C]glycine betaine. One mutant, strain LTG59, which exhibited reduced osmotic tolerance and a reduced rate of glycine betaine uptake was used for DNA sequence analysis and further studies.

DNA isolation and sequence analysis.

The nucleotide sequence of the L. monocytogenes LTG59 genomic DNA flanking the transposon was determined as follows. First, L. monocytogenes genomic DNA proximal to lacZ was cloned into E. coli DH5α (37), taking advantage of the ColE1 replication functions of Tn917-LTV3. Standard methods (37) were used for digestion with restriction enzymes, ligation, and gel electrophoresis, except where noted. Genomic DNA of mutant strain LTG59 was extracted as described by Flamm et al. (10) and was digested with XbaI, which restricts the transposon at the polylinker site (4). The desired DNA fragment, which was approximately 17 kb in length, was identified by probing with a 3-kb BglII fragment of the kanamycin resistance gene (neo) derived from Tn5 (provided by B. Walsh). DNA hybridization was detected by chemiluminescence with an ECL gene detection kit (Amersham) and nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher and Schuell) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. XbaI-digested genomic DNAs from 10403S and DP-L1044 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

The digested DNA was precipitated by the addition of ethanol and then brought to a concentration of 1 μg/ml in ligation reaction buffer (4). Five units of T4 DNA ligase (BRL-GIBCO) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 26°C overnight to allow the DNA to self-ligate. The DNA was precipitated by the addition of ethanol, redissolved in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0), and used to transform E. coli DH5α by electroporation with a gene pulser (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. E. coli transformants containing the desired plasmid (designated pLTG59X) were selected by kanamycin resistance, and the presence of the transposon fragment in pLTG59X was confirmed by Southern blot analysis with the probe for neo as described above.

L. monocytogenes genomic DNA was sequenced in both the forward and reverse directions by the Molecular Genetics Instrumentation Facility at the University of Georgia with an Applied Biosystems (ABI) 373 Sequencer and Taq terminator chemistry. Primers were synthesized with an ABI 394 DNA-RNA oligonucleotide synthesizer at the Protein Structure Laboratory of the University of California, Davis. The first primer used, F1 (GTTAAATGTACAAAATAACAGCGA), was derived from the sequence of Tn917-LTV3, on the proximal side of lacZ and about 70 bp from its end (38).

To obtain the nucleotide sequence flanking the other side of the transposon insertion, inverse PCR was carried out with a PTC-200 thermal cycler (MJ Research) using EcoRI-digested genomic DNA of strain 10403S as a template. Conditions used for PCR amplifications are described in reference 37. The size of the PCR-amplified DNA fragment was 1.5 kb, although the size expected from analysis of restriction endonuclease digests was about 7 kb. Apparently, a region of homology to one of the primers occurred within the DNA fragment, generating a smaller fragment which was amplified more efficiently. In view of this anomaly, a second amplification was performed with primers F11 (TGAACCACTTTTTGAGTAAATCATTTTTTG) and B9 (CAATAACTTGCCCAGTTAACGTGAGCGAAT), which yielded a 3.5-kb fragment. Both fragments were used in the determination of the nucleotide sequence of the entire coding region.

Analysis of the nucleotide sequence was performed with DNAsis version 3 software (Hitachi Software Engineering Co.). Peptide homology searches were carried out at the National Center for Biotechnology Information by using the BLAST programs.

Cloning the glycine betaine transport genes and complementation of E. coli WG439.

A 3,456-bp fragment of genomic L. monocytogenes DNA was amplified by PCR with primers G5 (GGGAATTCCCACTTTTGAGTAAATCATT), which contains a terminal EcoRI site followed by the sequence located 389 bp upstream from the start codon of the first open reading frame, and G3 (GGCTGCAGATGCATCTTCCTCCTAG), which contains a terminal PstI site and the complementary DNA sequence located 116 bp downstream from the stop codon of the third open reading frame. The amplified DNA fragment was ligated with pUC18 (43) at the EcoRI and PstI sites, and the resulting recombinant plasmid (pGBU18) was used to transform E. coli WG439 by electroporation. Transformants were selected by ampicillin resistance and were screened for glycine betaine transport and osmotic tolerance in M63 medium supplemented with NaCl and glycine betaine as described in the legend of Fig. 7. The identity of the insert in pUC18 was verified by DNA sequence analysis with the G3 and G5 primers and M13 forward and reverse primers (Pharmacia Biotech).

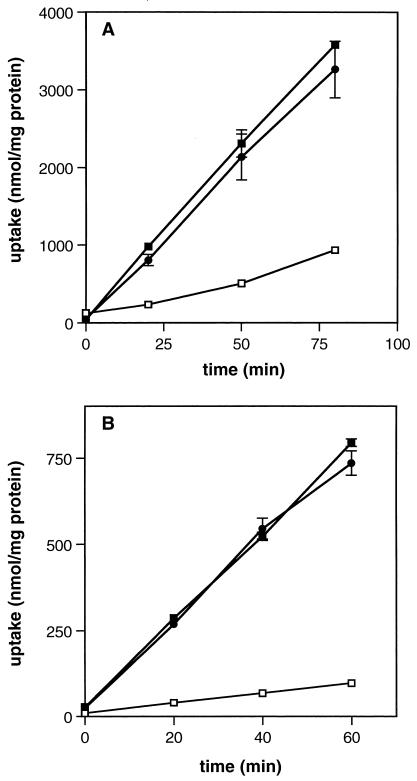

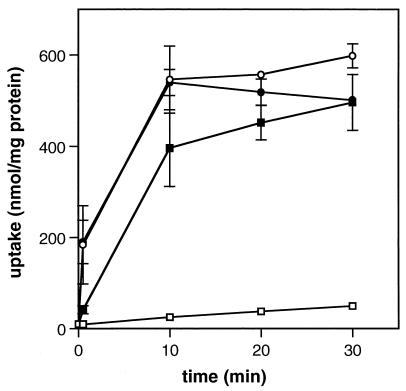

FIG. 7.

Restoration of the glycine betaine-dependent osmotic tolerance phenotype in E. coli WG439 transformants. For glycine betaine transport experiments (A), cultures grown aerobically at 37°C in M63 medium supplemented with ampicillin were used to inoculate M63 containing 0.4 M NaCl and ampicillin. After several hours of growth, 100 μM [14C]glycine betaine was added to initiate transport. For growth rate experiments (B), cultures were grown in M63 containing 0.7 M NaCl and 1 mM glycine betaine and ampicillin. The strains used were WG439 (■), WG439(pUC18) (○), and WG439(pGBU18) (□). The ranges of duplicate values are indicated by error bars.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequences of L. monocytogenes gbuA, gbuB, and gbC and flanking regions have been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF039835.

RESULTS

Isolation and analysis of glycine betaine transport-deficient mutants.

Mutants impaired in their ability to transport glycine betaine were isolated from a pool of Tn917-LTV3 L. monocytogenes mutants by screening for the loss of glycine betaine-dependent salt tolerance. Of approximately 3,600 mutants that were screened, 17 that displayed both a reduction in growth under osmotic stress conditions and a reduction in osmoregulated glycine betaine uptake were isolated. In addition, each mutant yielded a 17-kb DNA fragment that hybridized with the neo probe for Tn917-LTV3 after digestion with XbaI (data not shown); therefore, only one mutant, LTG59, was used for further studies. The growth characteristics in liquid medium of mutant LTG59 were compared to those of the parent strain 10403S and strain DP-L1044, a derivative of 10403S that contains the transposon Tn917-LTV3 in the hly locus (41) (Fig. 1). At 8% NaCl and 100 μM glycine betaine, the growth rate of the mutant strain LTG59 was about one-half that of the parent strains 10403S and DP-L1044, and the lag phase was twofold longer than those of the other strains. No differences in growth rates were observed among the strains in unstressed cultures grown at 30°C, nor were differences observed in cultures stressed with NaCl in the absence of glycine betaine (data not shown).

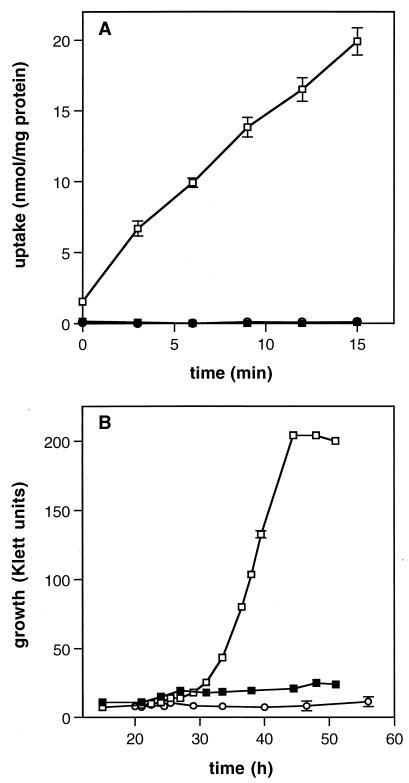

FIG. 1.

Growth characteristics of L. monocytogenes LTG59. Cultures of 10403S (■), DP-L1044 (●), and the glycine betaine transport mutant LTG59 (□) were grown in BHI and inoculated into modified Pine’s medium (1% inoculum). These cultures were grown to late log phase and used to inoculate (1%) modified Pine’s medium containing 100 μM glycine betaine. Cultures were grown at 30°C with 8% NaCl (A) or at 7°C without added NaCl (B). The ranges of duplicate values are indicated by error bars.

At 7°C, the growth rate of LTG59 was slightly lower (0.023 generation h−1) than those of 10403S and DP-L1044 (0.027 generation h−1), but the lag phases were indistinguishable (Fig. 1B). Hence, the effect of this mutation on chill tolerance is more subtle than it is on the osmotic tolerance of the cell.

Uptake rates of [14C]glycine betaine by LTG59, 10403S, and DP-L1044 were measured in modified Pine’s medium with 8% NaCl and at 7°C without additional salt (Fig. 2). While the glycine betaine uptake rate of DP-L1044 was identical to that of the parent strain 10403S (45 nmol of glycine betaine min−1 mg of cellular protein−1), the uptake rate of the mutant strain LTG59 (11 nmol of glycine betaine min−1 mg of cellular protein−1) was about fourfold lower than that of either of the other two strains in osmotically stressed cells (Fig. 2A). The effect of the mutation on chill-stimulated uptake was more pronounced than that on salt-activated uptake (Fig. 2B). For example, the rate of glycine betaine uptake by LTG59 (3.0 nmol of glycine betaine min−1 mg of cellular protein−1) was about eightfold lower than the rate by 10403S (25 nmol of glycine betaine min−1 mg of cellular protein−1). Taken together, the results of growth rate and uptake rate experiments indicate that the mutant strain LTG59 is impaired in the transport of glycine betaine at elevated osmolarity and at decreased temperature and that this mutation decreases the ability of the strain to tolerate elevated osmolarity and, to some extent, low temperature.

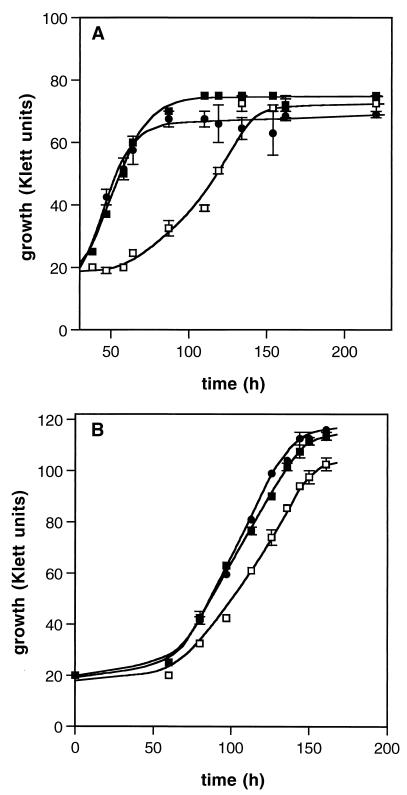

FIG. 2.

Glycine betaine transport activity of L. monocytogenes LTG59. Uptake of 100 μM [14C]glycine betaine was measured in 10403S (■), DP-L1044 (●), and the mutant LTG59 (□) grown to late log phase in modified Pine’s medium at 30°C with 8% NaCl (A) or at 7°C without added NaCl (B). Transport was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The ranges of duplicate values are indicated by error bars.

The fact that glycine betaine transport was not completely blocked is consistent with our previous finding that glycine betaine transport in L. monocytogenes may be the result of two transport systems: one uptake system which is responsible for most of the observed glycine betaine transport and another which has an absolute requirement for Na+ (11). It is therefore possible that the Tn917-LTV3 insertion eliminated the major activity but left the Na+-dependent activity intact. To determine if Na+ was required for the residual glycine betaine uptake activity observed in LTG59, uptake was assayed in ACES buffer containing 4% KCl or NaCl as the stressing salt (Fig. 3). While a deficiency in Na+ did not significantly affect the rate of glycine betaine uptake in 10403S, it did reduce the rate of uptake in LTG59 to about 1% that of the parent strain 10403S, indicating that nearly all of the residual activity observed in LTG59 is dependent on Na+.

FIG. 3.

Effect of Na+ and K+ deficiency on the uptake of glycine betaine in L. monocytogenes strains. Cultures of 10403S (○, ●) and LTG59 (□, ■) were grown and assayed for [14C]glycine betaine uptake in either 4% KCl (open symbols) or 4% NaCl (closed symbols) as described in Materials and Methods. The ranges of duplicate values are indicated by error bars.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the L. monocytogenes DNA fragment encoding the glycine betaine transport system.

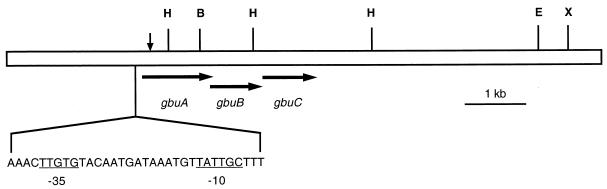

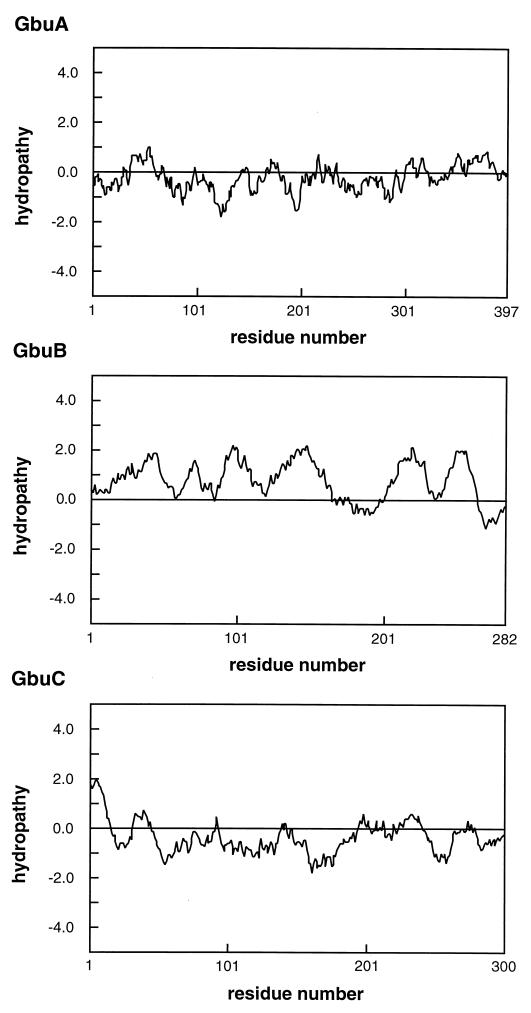

Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the L. monocytogenes DNA fragment flanking Tn917-LTV3 in strain LTG59 revealed the presence of three open reading frames (Fig. 4) with G+C contents of 39.8%, which is not atypical for members of the genus Listeria (9). The open reading frames are oriented in the same direction and are 1,194 (gbuA), 849 (gbuB), and 903 bp (gbuC) in length. The first open reading frame, gbuA, and the third open reading frame, gbuC, have an unusual translational start codon, TTG, a point that is discussed below. Also, the three open reading frames are closely arranged. The end of gbuA overlaps the beginning of gbuB by 8 bp, and the intergenic distance between gbuB and gbuC is 13 bp, suggesting that the three open reading frames are genetically arranged in an operon. Consistent with this suggestion is the fact that a region upstream from the first open reading frame is homologous to the promoter sequences of the opuA and proU operons (18, 28). Furthermore, a palindromic region 7 to 59 bp downstream of the stop codon of gbuC that could function as a transcription terminator was found (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Physical map of the cloned L. monocytogenes gbu region. The locations of the three open reading frames (gbuA, gbuB, and gbuC) and the direction of transcription are indicated by horizontal arrows. The start codon of gbuB overlaps with the stop codon of gbuA by 8 bp, and the intergenic distance between gbuB and gbuC is 13 bp. The sequence of the putative promoter is shown with the −35 and −10 regions underlined. The position of the Tn917-LTV3 insertion is indicated by the vertical arrow. Also shown are restriction sites for HindIII (H), BamHI (B), EcoRI (E), and XbaI (X).

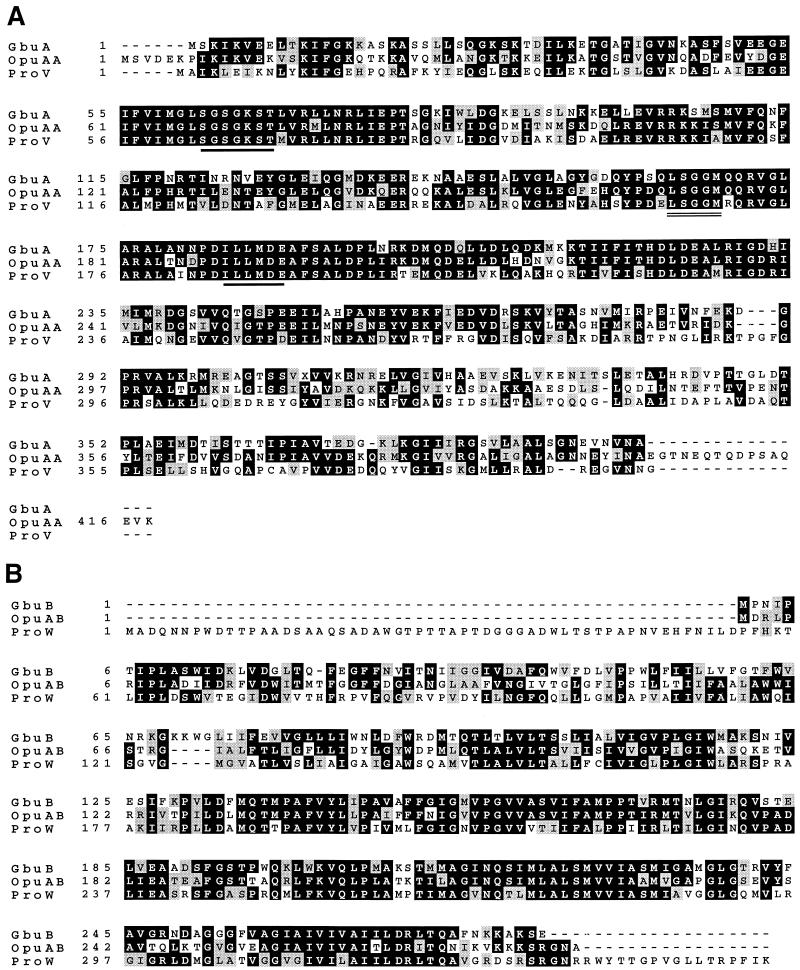

A comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of the three open reading frames with known protein sequences yielded the strongest homologies to two known glycine betaine transporters: OpuA from Bacillus subtilis (18) and ProU from E. coli (12). These transporters belong to the superfamily of ATP-dependent transport systems, which in bacteria usually consist of three kinds of protein subunits: an ATPase, a transmembrane protein, and a substrate-binding protein (1). The ATPase and transmembrane protein components form a membrane complex, while the substrate-binding protein is a soluble protein residing in the periplasm in gram-negative bacteria. In the absence of a periplasm, the substrate-binding protein is necessarily tethered to the cytoplasmic membrane of gram-positive bacteria (42). The open reading frame gbuA is predicted to encode a highly hydrophilic protein 397 amino acid residues in length (Mr, 43,624). Inspection of the deduced amino acid sequence of GbuA revealed 60.2 and 48.1% identities to OpuAA and ProV, respectively, which have been proposed to form the ATPase subunit of OpuA and ProU. Moreover, the GbuA sequence contains the Walker A and B motifs and Loop 3 (Fig. 5), the highly conserved sequences of the ATPase subunit of these transporters (15), providing further evidence that GbuA is the ATPase subunit.

FIG. 5.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences encoded by gbu from L. monocytogenes with the homologous systems from B. subtilis and E. coli. Identical amino acids are shaded in black, and conservative substitutions are in gray. (A) The sequence of GbuA is compared with those of OpuAA from B. subtilis and ProV from E. coli. The Walker motifs A and B, two highly conserved sequences found in ATP-dependent transporters, are underlined. Another highly conserved region, Loop 3, is indicated by a double underline. (B) Comparison of GbuB with the corresponding OpuAB protein from B. subtilis and ProW protein of E. coli. (C) Comparison of GbuC with the glycine betaine binding protein OpuAC from B. subtilis and ProX protein from E. coli. The position of the predicted cleavage site of the signal peptide is indicated by the vertical line (between residues 20 and 21 of GbuC).

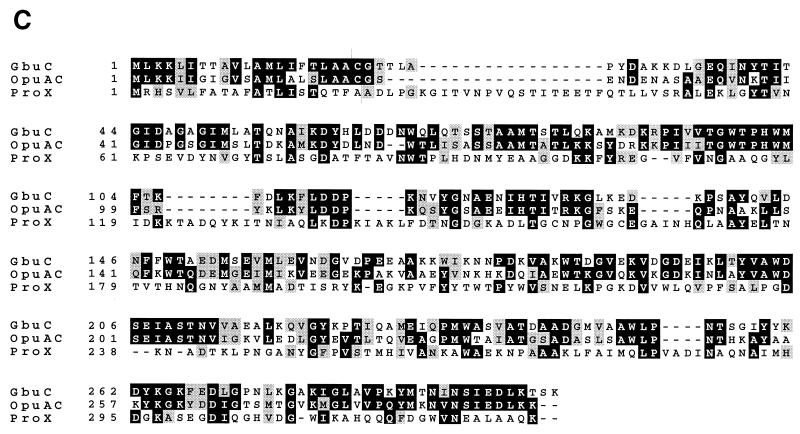

The gbuB open reading frame encodes a hydrophobic protein 282 amino acid residues in length (Mr, 30,917). Analysis of the hydropathic characteristics of the amino acid sequence indicates that the protein contains six segments with sufficient hydrophobicity and length to span the membrane (Fig. 6) (24). Consistent with transmembrane proteins in general, these hydrophobic regions occur in sections of the sequence that are predicted to be largely helical (36). In addition, the deduced amino acid sequence is homologous to OpuAB (54.6% identity) from B. subtilis and ProW (44.7% identity) from E. coli, which are the transmembrane protein components of their respective transporters (Fig. 5). The gbuB gene product is therefore proposed to form a transmembrane channel.

FIG. 6.

Hydropathy profiles of GbuA, GbuB, and GbuC. The hydrophobicity of the protein is represented as a hydropathy index, computed by using the method of Kyte and Doolittle (24). A window of 20 amino acids was used.

The final open reading frame, gbuC, is predicted to encode a relatively hydrophilic, 300-amino-acid protein (Mr, 33,274) which is presumed to be the substrate-binding protein. The L. monocytogenes sequence has significantly greater homology to OpuAC (Fig. 5) (51.0% identity) than to ProX (14.7% identity), as expected considering the differing structural requirements of the binding protein in gram-positive versus -negative bacteria. It is noteworthy that a 20-amino-acid region at the N terminus of GbuC contains a high proportion of hydrophobic residues (Fig. 6), characteristic of signal peptides. Furthermore, both GbuC and OpuAC contain the signal peptide consensus sequence (Leu-Ala-Ala-Cys) of substrate-binding proteins from gram-positive bacteria (19, 42). This sequence is of particular significance, since in this class of proteins, proteolytic cleavage has been shown to occur between Ala and Cys to provide an N-terminal Cys, the point of attachment of the protein to the cellular membrane (19, 42).

Functional complementation of E. coli WG439.

To verify that gbu from L. monocytogenes encodes a glycine betaine transport system, complementation experiments were carried out with E. coli WG439, a strain which is devoid of glycine betaine transport activity, and pGBU18, which harbors the gbu genes. Osmotically stressed transformants containing pGBU18 effectively transported glycine betaine (Fig. 7A), but unstressed transformants did not (data not shown). The enhancement of glycine betaine-dependent osmotic tolerance of the culture by pGBU18 was also observed (Fig. 7B). At 0.7 M NaCl and 100 μM glycine betaine, growth was observed in strain WG439(pGBU18) but not in WG439(pUC18) or in untransformed cells. In the absence of glycine betaine in the stressing medium, none of the strains grew, and in the absence of NaCl stress, all three strains grew at approximately the same rate (0.95 to 1.0 generation h−1). Hence, it appears that not only was glycine betaine uptake activity detectable but also it was sufficient to confer osmotic tolerance upon the complemented strain.

DISCUSSION

The intracellular accumulation of glycine betaine in L. monocytogenes contributes significantly to the osmotic tolerance of the cell (3, 21). Furthermore, the accumulation is effected by transport of this osmolyte from the growth medium (21, 31) or food substrate (39). Previously we showed that osmoregulated glycine betaine uptake is coupled to Na+ transport (11) but that an additional transporter in L. monocytogenes was likely. Evidence of a second glycine betaine transport system in L. monocytogenes that belongs to the superfamily of ATP-dependent transporters and is not Na+ dependent has been provided in this report.

The deduced amino acid sequences of the three open reading frames showed extensive homology with OpuA from B. subtilis and somewhat less homology with ProU from E. coli. Both of these systems are ATP-dependent glycine betaine transporters. In addition, the nucleotide sequence revealed that the three open reading frames are in close proximity. In fact, the end of gbuA overlaps the start of gbuB by 8 nucleotides. Interestingly, proU, which encodes a second betaine transporter from B. subtilis (26), and proU from E. coli (12) both show similar overlaps between their first and second open reading frames. Whether these overlaps are indicative of regulatory elements or are examples of genetic economy (22) is unclear at this time. Another unusual feature is the TTG start codon of gbuA and gbuC. While this start codon is rare, it has been reported for L. monocytogenes (25, 29). Moreover, 13% of all genes in B. subtilis start with the TTG codon (23). In the case of the gbu genes, the view that TTG is the start codon for two of the genes in the transport system arose from the observed homology with the deduced N-terminal sequences of OpuAA and OpuAC of B. subtilis upstream from the first ATG codon of GbuA and GbuC (59 and 58%, respectively). Also, located 7 and 8 bp upstream from the putative TTG start codons of gbuA and gbuC, respectively, were GA-rich regions which could serve as ribosome binding sites. In addition, similar GA-rich regions optimally spaced for ribosome binding from the first occurring ATG codons of both gbuA and gbuC were not found.

While the putative promoter region of the gbu operon shows extensive homology to the promoters of opuA and proU (18, 28), none of these promoters contains consensus sequences recognized by any known sigma factor from gram-positive or -negative bacteria (13, 14). Even so, Becker et al. (2) recently reported that a mutation in the stress transcription factor ςB of L. monocytogenes decreased the glycine betaine-dependent osmotic tolerance of the cell and reduced the rate of glycine betaine transport. One explanation for this apparent incongruity is that ςB might affect transport activity indirectly via modulation of a regulatory protein that controls gbu expression or betaine transport activity. However, when one also considers that the decrease in glycine betaine uptake in the ςB knockout mutant reported by Becker et al. (2) was less than twofold, a simpler explanation is that a second, ςB-dependent, transporter occurs in L. monocytogenes.

The fact that glycine betaine uptake was not completely blocked in the osmotically stressed mutant strain LTG59 is another indication that one additional transport system is present in L. monocytogenes. Furthermore, when Na+ was omitted from the assay mixture, glycine betaine uptake activity was virtually eliminated in LTG59 but remained unchanged in the parent strain, 10403S. Taken together, these results indicate that two transport systems occur in L. monocytogenes: a highly active ATP-dependent transporter and a less active Na+-glycine betaine symporter. Multiple transport systems in prokaryotes are not uncommon, and such systems have been observed for glycine betaine transport. In B. subtilis, three glycine betaine uptake systems, encoded by opuA, opuD, and opuC (proU), have been identified (17, 26), and two each have been identified in Staphylococcus aureus (35, 40) and E. coli (46).

Why should L. monocytogenes have two osmotically regulated glycine betaine transport systems? Apparently glycine betaine accumulation is an important process in L. monocytogenes, conferring both osmotic and chill tolerance (21). Furthermore, it is accumulated in unstressed cells (21), albeit to relatively low concentrations, presumably to contribute to the high turgor pressure found in gram-positive bacteria. Unlike the transport systems in S. aureus (35, 40) and E. coli (46), both transporters in L. monocytogenes appear to give low Km values (11, 21, 28a), which also indicates the importance of glycine betaine to this species. However, these systems are not truly redundant considering the differences in their relative rates of activity and modes of energy coupling. In assigning separate functions to these transporters, it would be an oversimplification to assume that the major role of the ATP-dependent system is merely the transport of glycine betaine in the absence of Na+, since is unlikely that an Na+-free environment would be encountered in nature. It is more likely a question of energetics. Na+-metabolite symporters are generally single transmembrane proteins, which are much simpler and more economical for the cell to manufacture than multicomponent, ATP-dependent transporters. Moreover, although little is known about the stoichiometry of these transport systems, it is generally accepted that transport of nutrients by ion-metabolite symporters is also less costly, energetically, than ATP-coupled transport. However, a benefit of the ATP-dependent transporters is that they are able to concentrate metabolites to a much higher level than ion-metabolite symporters. Hence, symport may be the primary route of glycine betaine accumulation in energy-depleted cells, while the ATP-coupled system may be more important during rapid growth, when energy is plentiful.

Finally, disruption of gbu by transposon insertion significantly reduced chill-activated transport, indicating that gbu is responsible for most of the chill-activated uptake. This result agrees with our previous observation that the Na+-glycine betaine symporter could not support chill-activated transport in vesicles (11). Whether the residual chill-activated transport is a result of passive diffusion or is due to this or another transport system needs to be addressed to elucidate the specific functions of each transport system in nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. M. Wood for the culture of E. coli and R. B. Walsh for DNA samples and for the cultures of L. monocytogenes. We also thank G. M. Smith for helpful discussions.

This research was supported by USDA grant 9601744.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames G F-L. Structure and mechanism of bacterial periplasmic transport systems. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1988;20:1–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00762135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker L A, Cetin M S, Hutkins R W, Benson A K. Identification of the gene encoding the alternative sigma factor ςB from Listeria monocytogenes and its role in osmotolerance. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4547–4554. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4547-4554.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beumer R R, Te Giffel M C, Cox L J, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Effect of exogenous proline, betaine, and carnitine on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in a minimal medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1359–1363. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1359-1363.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilli A, Portnoy D A, Youngman P. Insertional mutagenesis of Listeria monocytogenes with a novel Tn917 derivative that allows direct cloning of DNA flanking transposon insertions. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3738–3744. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3738-3744.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole M B, Jones M V, Holyoak C. The effect of pH, salt concentration and temperature on the survival and growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conner D E, Brackett R E, Beuchat L R. Effect of temperature, sodium chloride, and pH on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in cabbage juice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:59–63. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.1.59-63.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csonka L N, Hanson A D. Prokaryotic osmoregulation: genetics and physiology. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1991;45:569–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.45.100191.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culham D E, Lasby B, Marangoni A G, Milner J L, Steer B A, van Nues R W, Wood J M. Isolation and sequencing of Escherichia coli gene proP reveals unusual structural features of the osmoregulatory proline/betaine transporter, ProP. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:268–276. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes: a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flamm R K, Hinrichs D J, Tomashow M F. Introduction of pAMβ1 into Listeria monocytogenes by conjugation and homology between native L. monocytogenes plasmids. Infect Immun. 1984;44:157–161. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.1.157-161.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerhardt P N M, Smith L T, Smith G M. Sodium-driven, osmotically activated glycine betaine transport in Listeria monocytogenes membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6105–6109. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6105-6109.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gowrishankar J. Nucleotide sequence of the osmoregulatory proU operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1923–1931. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.1923-1931.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helmann J D, Chamberlin M J. Structure and function of bacterial sigma factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:839–872. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.004203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins C F. ABC transporters: from microorganism to man. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juneja V K, Foglia T A, Marmer B S. Heat resistance and fatty acid composition of Listeria monocytogenes: effect of pH, acidulant, and growth temperature. J Food Prot. 1998;61:683–687. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.6.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kappes R M, Kempf B, Bremer E. Three transport systems for the osmoprotectant glycine betaine operate in Bacillus subtilis: characterization of OpuD. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5071–5079. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5071-5079.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempf B, Bremer E. OpuA, an osmotically regulated binding protein-dependent transport system for the osmoprotectant glycine betaine in Bacillus subtilis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16701–16713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempf B J, Gade J, Bremer E. Lipoprotein from the osmoregulated ABC transport system OpuA of Bacillus subtilis: purification of the glycine betaine binding protein and characterization of a functional lipidless mutant. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6213–6220. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.20.6213-6220.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko R. Adaptation mechanisms of Listeria monocytogenes under hyperosmotic and low temperature stress. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Davis; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko R, Smith L T, Smith G M. Glycine betaine confers enhanced osmotolerance and cryotolerance on Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:426–431. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.2.426-431.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozak M. Comparison of initiation of protein synthesis in procaryotes, eucaryotes, and organelles. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:1–45. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.1.1-45.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunst F, Ogasawara N, Moszer I, Albertini A M, Alloni G, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leimeister-Wachter M, Domann E, Chakraborty T. Detection of a gene encoding a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C that is co-ordinately expressed with listeriolysin in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:361–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Y, Hansen J N. Characterization of a chimeric proU operon in a subtilin-producing mutant of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6874–6880. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6874-6880.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May G, Faatz E, Lucht J M, Harrdt M, Bolliger M, Bremer E. Characterization of the osmoregulated Escherichia coli proU promoter and identification of ProV as a membrane-associated protein. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1521–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Mendum, M., and L. T. Smith. Unpublished results.

- 29.Mengaud J, Braun-Breton C, Cossart P. Identification of phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C activity in Listeria monocytogenes: a novel type of virulence factor? Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:367–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patchett R A, Kelly A F, Kroll R G. Transport of glycine betaine by Listeria monocytogenes. Arch Microbiol. 1994;162:205–210. doi: 10.1007/BF00314476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perroud B, Le Rudulier D. Glycine betaine transport in Escherichia coli: osmotic modulation. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:393–401. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.1.393-401.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pine L, Franzus M, Malcolm G. Guanine is a growth factor for Legionella species. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;23:163–169. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.1.163-169.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pine L, Malcom G, Brooks J, Daneshvar M. Physiological studies on the growth and utilization of sugars by Listeria species. Can J Microbiol. 1989;35:245–254. doi: 10.1139/m89-037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pourkomailian B, Booth I R. Glycine betaine transport by Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for feedback regulation of the activity of the two transport systems. Microbiology. 1994;140:3131–3138. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rost B, Sander C, Schneider R. PHD—an automatic mail server for protein secondary structure prediction. CABIOS. 1994;10:53–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw J H, Clewell D B. Complete nucleotide sequence of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-resistance transposon Tn917 in Streptococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:782–796. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.782-796.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith L T. Role of osmolytes in adaptation of osmotically stressed and chill-stressed Listeria monocytogenes grown in liquid media and on processed meat surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3088–3093. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3088-3093.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stimeling K W, Graham J E, Kaenjak A, Wilkinson B J. Evidence for feedback (trans) regulation of, and two systems for, glycine betaine transport by Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 1994;140:3139–3144. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun A N, Camilli A, Portnoy D A. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3770–3778. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3770-3778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sutcliffe I C, Russell R R B. Lipoproteins of gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1123–1128. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1123-1128.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takeshita S, Sato M, Toba M, Masahashi W, Hashimoto-Gotoh T. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ α-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene. 1987;61:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verheul A, Rombouts F M, Beumer R R, Abee T. An ATP-dependent l-carnitine transporter in Listeria monocytogenes Scott A is involved in osmoprotection. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3205–3212. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3205-3212.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker S, Archer P, Banks J. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes at refrigeration temperatures. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;68:157–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wood J M. Proline porters effect the utilization of proline as nutrient or osmoprotectant for bacteria. J Membr Biol. 1988;106:183–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01872157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yancey P H, Clark M E, Hand S C, Bowlus R D, Somero G N. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982;217:1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]