Abstract

Toluene–o-xylene monooxygenase is an enzymatic complex, encoded by the touABCDEF genes, responsible for the early stages of toluene and o-xylene degradation in Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. In order to identify the loci involved in the transcriptional regulation of the tou gene cluster, deletion analysis and complementation studies were carried out with Pseudomonas putida PaW340 as a heterologous host harboring pFB1112, a plasmid that allowed regulated expression, inducible by toluene and o-xylene and their corresponding phenols, of the toluene–o-xylene monooxygenase. A locus encoding a positive regulator, designated touR, was mapped downstream from the tou gene cluster. TouR was found to be similar to transcriptional activators of aromatic compound catabolic pathways belonging to the NtrC family and, in particular, to DmpR (83% similarity), which controls phenol catabolism. By using a touA-C2,3O fusion reporter system and by primer extension analysis, a TouR cognate promoter (PToMO) was mapped, which showed the typical −24 TGGC, −12 TTGC sequences characteristic of ς54-dependent promoters and putative upstream activating sequences. By using the reporter system described, we found that TouR responds to mono- and dimethylphenols, but not the corresponding methylbenzenes. In this respect, the regulation of the P. stutzeri system differs from that of other toluene or xylene catabolic systems, in which the hydrocarbons themselves function as effectors. Northern analyses indicated low transcription levels of tou structural genes in the absence of inducers. Basal toluene–o-xylene monooxygenase activity may thus transform these compounds to phenols, which then trigger the TouR-mediated response.

In bacteria, the ability to switch on different metabolic routes at the right time is fundamental for successful adaptation to new environmental conditions. Regulatory elements that control the expression of a specific set of genes play a primary role in this regard.

Known regulators for toluene catabolism include XylR, which controls the transcription of the xyl upper operon of Pseudomonas putida PaW1, and TbuT, which controls the expression of toluene-3-monooxygenase in Burkholderia pickettii PKO1. Both XylR and TbuT belong to a distinct subfamily of the major family of NtrC-like regulators and positively control the transcription of catabolic operons from a distinct class of promoters (5, 16, 17). DmpR and PhhR, which control phenol catabolism in Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 and P. putida P35X, respectively, belong to the same subfamily (27, 40).

Although these regulators control the expression of very different catabolic pathways and enzymes, they appear to act in a similar manner. All of them are monocomponent regulatory systems, able to recognize and to respond directly to the presence of small effector molecules (37). Like eukaryotic transcriptional factors, these regulators are composed of distinct functional domains (for reviews, see references 26 and 29). In XylR and DmpR, it was demonstrated that the amino-terminal domain (A domain) acts as the receiver module, able to directly recognize aromatic compounds as effectors (8, 12, 38, 39). It thus confers specificity to the regulatory protein and is the most variable domain among the regulators belonging to the NtrC subfamily. The A domain is immediately adjacent to the highly conserved central C domain, which contains a nucleotide binding motif. The C domain is believed to interact with the ς54 RNA polymerase and to hydrolyze ATP. Finally, the carboxy-terminal D domain contains a helix-turn-helix motif putatively involved in DNA binding (28, 31).

Regulators belonging to the NtrC family control transcription from invariant −24 (GG), −12 (GC) promoters recognized by RNA polymerase that utilizes the alternative factor ς54 and bind to specific DNA sequences (upstream activating sequences [UASs]), usually located 100 to 200 bp upstream from the promoter they control (7, 20, 21).

Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1 degrades toluene and o-xylene through two successive hydroxylation steps of the aromatic ring (2) catalyzed by toluene–o-xylene monooxygenase (ToMO). From a P. stutzeri OX1 gene library, we previously isolated the cosmid pFB3401, which codes for the enzymes involved in the transformation of toluene and o-xylene into their corresponding ring fission products, and mapped the ToMO gene cluster (touABCDEF) to a 5.6-kb DraI-EcoNI fragment (3, 4).

In the present work, we report the identification of the elements involved in the regulation of the ToMO expression, namely the ToMO regulatory gene (touR) and the TouR-responsive ToMO promoter (PToMO).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. Plasmids were isolated from P. putida as described by Hansen and Olsen (14) and from Escherichia coli by standard procedures (33) or by the use of purification kits purchased from Qiagen. Recombinant plasmids were constructed by standard procedures (33) and introduced into the bacterial host strains by electroporation (11). E. coli JM109 (43) was routinely used for plasmid construction and selection.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| P. putida PaW340 | Tol−o-Xyl− Dmp− Cre− Trp− Smr | 13 |

| E. coli JM109 | recA1 hsd17 thi Δ (lac-proAB) (F′ traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15) | 43 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFB3401 | Tcr; pLAFR1 derivative, contains 28-kb EcoRI partial DNA fragments from P. stutzeri OX1 | 3 |

| pFB1112 | Tcr; partial EcoRI deletion of pFB3401 | 3 |

| pFB1230 | Tcr; partial EcoRI deletion of pFB3401 | 3 |

| pFB1198 | Tcr; partial EcoRI deletion of pFB3401 | 3 |

| pGEM-11Z | Apr; cloning vector | Promega |

| pSP72 | Apr; cloning vector | Promega |

| pLAFR3 | Tcr; cloning vector | 41 |

| pMP7285 | Apr; pSP72 derivative, contains an 8.5-kb ApaI-ApaI fragment of pFB1198 cloned in pGEM-11Z and then transferred in pSP72 as an XhoI-XbaI cassette | This work |

| pFP3067 | Tcr; pLAFR3 derivative, contains a 6.7-kb ApaI-NotI fragment of pFB1198 | This work |

| pFP3038 | Tcr; 2.9-kb ApaI-KpnI deletion of pFP3067 | This work |

| pFP3028 | Tcr; 1-kb KpnI-HindIII deletion of pFP3038 | This work |

| pGEM-3Z | Apr; cloning vector | Promega |

| pBZ3120BS | Apr; pGEM-3Z derivative, contains a 2-kb BamHI-XhoI P. stutzeri OX1DNA fragment coding for C2,3O | This work |

| pFM1020 | Apr; pBZ2120BS derivative, contains a 4.0-kb HindIII fragment of pFB1112 | This work |

| pKGB4 | Kmr; cloning vector, compatible with pLAFR1 and pLAFR3 | 32 |

| pKGB4213 | Kmr; partial EcoRI deletion of pFB1112 cloned in pKGB4 | This work |

| pPP4062 | Kmr; pKGB4 derivative, contains the 5.7-kb SacI-SacI fragment of pFM1020 | This work |

| pPP4162 | Kmr; same insert as pPP4062 in the opposite orientation | This work |

| pPP4052 | Kmr; as pPP4062, BamHI-BamHI deletion | This work |

| pPP4043 | Kmr; as pPP4062, BamHI-ClaI deletion | This work |

| pPP4056 | Kmr; as pPP4062, HpaI-ClaI deletion | This work |

| pPP4035 | Kmr; as pPP4062, HpaI-BamHI deletion | This work |

| pPP4145 | Kmr; as pPP4162, HpaI-HpaI deletion | This work |

Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin; Sm, streptomycin; Tc, tetracycline; Tol, toluene; o-Xyl, o-xylene; Cre, cresols; Dmp, dimethylphenols; Trp, tryptophan.

Recombinant plasmids of the FB series were previously isolated and described by Bertoni et al. (3). To obtain the plasmids of the FP series, the 8.5-kb ApaI-ApaI fragment from pFB1198 was cloned in pGEM11Z (Promega) and then transferred in pSP72 (Promega) as an XhoI-XbaI cassette, giving plasmid pMP7285. Deletions were carried out in pMP7285, and the inserts were transferred in pLAF3 (41) as BamHI-BamHI cassettes.

The reporter system was constructed by fusion of DNA fragments with a catechol 2,3-dioxygenase (C2,3O)-encoding gene. Plasmid pBZ3120BS contains the P. stutzeri OX1 C2,3O structural gene in a 2-kb BamHI-XhoI fragment cloned into the pGEM-3Z vector. A 4-kb HindIII fragment placed immediately upstream from the ToMO gene cluster and which partially overlapped the first ToMO gene (touA) (4) was cloned in the correct orientation into the HindIII site of pBZ3120BS upstream from the P. stutzeri OX1 C2,3O gene, giving plasmid pFM1020. The reporter system obtained was excised as a SacI cassette by using a SacI site present in the cloned HindIII fragment distal from the reporter gene. The SacI cassette was then cloned in the broad-host-range vector pKGB4 (32), leading to plasmid pPP4062. Deletions in the 4-kb HindIII fragment were obtained in pFM1020, and then the SacI cassettes were transferred in pKGB4, leading to the formation of pPP4052, pPP4043, pPP4056, and pPP4035. Plasmid pPP4145 was obtained directly from pPP4162, which carries the same insert as pPP4062, but cloned in the opposite orientation.

Media and culture conditions.

P. putida PaW340 and E. coli JM109 were routinely grown in Luria broth (LB) (33) at 30 and 37°C respectively. Ampicillin, kanamycin, and tetracycline were used in selective media at 150, 30, and 25 μg/ml, respectively. In induction experiments, P. putida PaW340 cells were grown in M9 medium (19) containing 20 mM malate, 0.05 mM tryptophan, and the appropriate antibiotic(s). The overnight cultures were diluted in the same medium and grown for 2 h before adding the inducer. As inducers, aromatic compounds were supplied at a final concentration of 2 mM (dimethylphenols [DMPs] and cresols) or in the vapor phase (o-xylene and toluene). In testing for enzymatic activities, cells were harvested after an additional 3 h of growth, in the exponential growth phase (optical density at 600 nm, ≅0.7). Samples for RNA extraction were collected at 30-min intervals after inducer addition.

Enzyme assays.

ToMO activity was determined in whole cells by monitoring the increase in concentration of phenolic compounds in the medium with an established colorimetric assay (3, 24). Briefly, a culture grown as described above was washed twice in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) and suspended in the same buffer to obtain A600 ≅2. Glucose (final concentration, 5 mM) and 35 μl of 4% (vol/vol) toluene in N,N-dimethylformamide were added to the cell suspension. At 2-min intervals after incubation at 30°C, 1-ml samples were collected and mixed with 100 μl of 1 M NH4OH and 25 μl of 2% 4-aminoantipyrine. After the addition of 25 μl of 8% K3Fe(CN)6, the samples were briefly centrifuged (14,000 × g), and the A500 of the supernatant was measured. Phenolic compound concentrations were calculated by reference to a standard curve for m-cresol. Cells were resuspended in 0.1 M NaOH and incubated in boiling water for 20 min before the protein concentration assay was performed.

C2,3O was assayed in crude extracts by measuring the rate of formation of the ring fission product of catechol (30) in a 1.5-ml reaction mixture containing 3 mM catechol, 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), and cell extract. Crude extracts were prepared as follows. Cells from 10 to 20 ml of culture (depending on the A600) were collected and resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (KCl, 150 mM; MgCl2, 5 mM; dithiothreitol, 1 mM; Triton X-100, 0.01%; Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 20 mM). Fifty microliters of glass beads (150 to 212 μm in diameter; Sigma Chemical Co.) was added to the cell suspension in a microcentrifuge tube. The sample was frozen in liquid nitrogen and vortex mixed for 2 min. This step was repeated three times. Two hundred microliters of lysis buffer was then added to the sample, and after a brief mixing, cell debris was removed by centrifugation (5 min at 14,000 × g) to give the crude extract used in the assay.

The protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (Sigma Chemicals Co.), with bovine serum albumin as a protein standard.

Specific activities were reported as nanomoles of compounds produced per minute per milligram of cell protein.

RNA purification and primer extension analysis.

RNA was isolated from P. putida PaW340 cells carrying pFB1112 grown as described before. Cells from 1.5-ml samples were collected by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 4°C), resuspended in 200 μl of lysis buffer (sodium acetate [pH 5.5], 20 mM; sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.5%; EDTA, 1 mM), and extracted for 5 min at 65°C with 200 μl of prewarmed phenol saturated with 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5). After centrifugation, the aqueous phase was extracted with an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1 [vol/vol]), and the nucleic acids were precipitated by the addition of 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 6.0) and 3 volumes of absolute ethanol. The precipitate was suspended in 50 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water and incubated for 15 min at 37°C with 20 U of RNase-free DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim). The RNA was subsequently phenol extracted twice, ethanol precipitated, and dissolved in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water. The RNA concentration was estimated by measuring the OD260 and OD280.

The transcription start sites of the ToMO operon and of touR were determined by primer extension analysis. The oligonucleotides EXT1PT (5′-TCAATCCGGTCAGGGCGGTG-3′) and EXT1PR (5′-TATAACACCTGACTGGAAAC-3′), which are complementary to the regions spanning from +101 to +120 and from +108 to +127 downstream from the ToMO and the TouR promoters, respectively, were 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham), annealed to 50 μg of total RNA, and extended in the presence of reverse transcriptase. The extended products were analyzed on 6% urea–polyacrylamide gels.

In Northern hybridization analyses, 20 μg of total RNA samples was denatured with formamide and formaldehyde, analyzed at 4°C on a 1.2% agarose gel containing formaldehyde, transferred to a Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham) (33), and then probed with touA. The probe was isolated from pMZ1201 (4) as a SalI-MluI 1,330-bp fragment and labeled with [α-32P]dATP by using a random primer DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim).

Nucleotide sequence determination and sequence analysis.

Nucleotide sequences were determined directly from plasmids by the dideoxy chain termination technique (34) with the Deaza G/AT7 Sequencing Mixes kit according to the supplier’s instructions (Pharmacia Biotech). [α-35S]dATP and T7, SP6, or specific synthetic primers were used. The sequences were analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, Wis.) GCG software package (10) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLASTP program (1).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of touR has been submitted to the EMBL data bank under accession no. AJ005663.

RESULTS

Mapping the regulatory loci controlling P. stutzeri OX1 ToMO expression.

To check the inducibility of ToMO and to initially map the elements involved in ToMO regulation, we assayed ToMO activity in the heterologous host, unable to degrade hydrocarbons and phenols, with P. putida PaW340 harboring different plasmids and grown under different cultural conditions.

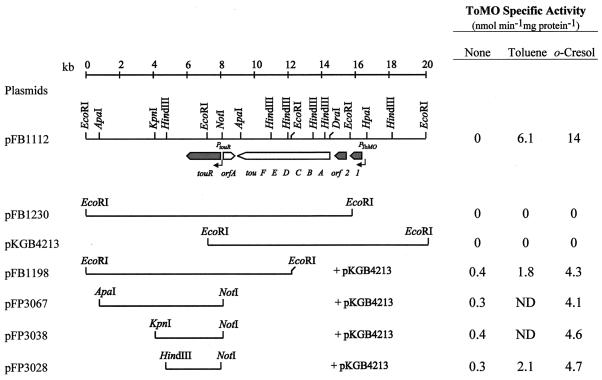

In P. putida PaW340 cells carrying pFB1112, ToMO expression appeared to be tightly regulated (Fig. 1). ToMO activity was undetectable in P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cells grown in the absence of inducers, but increased upon exposure to both toluene and o-cresol, indicating that its insert contains all of the elements involved in ToMO regulation. Further deletions and complementation studies allowed mapping of the loci involved in ToMO regulation. The deletion of a single EcoRI fragment at either the 5′ or the 3′ end of the insert cloned in pFB1112 led to the loss of ToMO expression. However, pFB1198 restored the regulated expression of ToMO in P. putida PaW340(pKGB4213). Thus, considering the previously determined direction of transcription of the tou genes (4), we could tentatively map a cis-acting element(s) to the 4.5-kb EcoRI fragment at the right end of the DNA fragment cloned in pFB1112, whereas a trans-acting element could be present in the DNA fragment cloned in pFB1198.

FIG. 1.

Restriction maps of pFB1112, which allows regulated expression of ToMO, and its derivatives. Only the relevant restriction sites are shown. Under the map of pFB1112, the white arrows indicate the location and the direction of transcription of the previously described ToMO gene cluster (touABCDEF) and orfA, putatively coding for a transposase (4). Shaded arrows indicate the regulatory gene (touR) and two additional ORFs (orf1 and orf2) identified in this work. Black thin arrows represent the touR (PtouR) and ToMO (PToMO) promoters. ToMO specific activity was measured in P. putida PaW340 cells carrying the indicated plasmids grown in the absence or in the presence of either toluene or o-cresol supplied as inducers. A minimum of three independent experiments (variation within 10%) were performed for each strain; results from representative assays are shown. ND, not determined.

Because pFB1198 was able to restore the regulated expression of ToMO in P. putida PaW340(pKGB4213) cells, we subcloned single DNA fragments from the pFB1198 insert to further define the complementing region. Each fragment was subcloned in the broad-host-range vector pLAF3, and the plasmids obtained, pFP3067, pFP3038, and pFB3028, were transformed into P. putida PaW340(pKGB4213) cells. All of the plasmids tested were found to restore regulated ToMO expression (Fig. 1). The lower levels of ToMO activity in the complementation assays might be due to unbalanced plasmid copy number and/or gene dosage. Similar results were obtained when each insert was cloned in the other orientation with respect to the Plac promoter of the vector (data not shown), suggesting that in all of the plasmids tested, the trans-acting element could be expressed from its own promoter. The complementing region was thus localized to the 2.8-kb insert cloned in pFP3028.

Nucleotide sequence of touR and determination of its 5′-mRNA start.

Approximately 2,200 bp of the 2.8-kb fragment cloned in pFP3028 was sequenced starting from the NotI site. Sequence analysis revealed a complete open reading frame (ORF) in the same direction of transcription of the tou structural genes, putatively coding for a 569-amino-acid polypeptide with an expected molecular mass of approximately 67 kDa, named touR.

Comparison of the TouR deduced amino acid sequence with those in a nonredundant peptide sequence database revealed a high degree of similarity to several members of the NtrC family of transcriptional activators involved in the regulation of aromatic compound catabolic pathways (5, 16, 27, 40). TouR revealed the highest degree of similarity to DmpR and PhhR (83%), which regulate operons for catabolism of phenols in Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600 and P. putida P35X, respectively, whereas the similarities to XylR (80%) and TbuT (65%), which regulate operons involved in catabolism of methylbenzenes, such as m-xylene, p-xylene, and toluene, in P. putida PaW1 and toluene in B. pickettii PKO1, respectively, were lower. PILEUP multiple sequence alignment analyses (not shown) allowed the recognition of typical A, C, and D domains in TouR, where putative ATP-binding (amino acids [aa] 263 to 269; GETGVGK) and helix-turn-helix DNA-binding (aa 533 to 549; AM-X9-AA-X2-LG) motifs are conserved. Pairwise comparisons of each domain revealed that the C and D domains of TouR were highly similar to the corresponding domains of DmpR (90 and 89%, respectively) and XylR (89 and 81%, respectively). Interestingly, the A domain of TouR was found to be more similar to that of DmpR (83%) than to that of XylR (77%) or TbuT (66%). Because the A domain is believed to confer specificity to these regulatory proteins, differences could be expected between TouR and other NtrC-like regulators of methylbenzene catabolism with regard to their effector range.

The sequence upstream from touR did not reveal any significant homology compared with the corresponding region of dmpR or xylR. However, a putative ς70-dependent −35 TTGG, −10 TAAT promoter was identified 223 bp upstream from the touR ATG initiation codon.

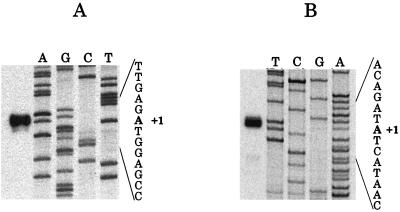

To identify the transcription start of touR in vivo, primer extension analysis was performed. By using the oligonucleotide EXT1PR (see Materials and Methods), a single band, corresponding to an A residue located 7 nucleotides (nt) downstream from the −10 TAAT consensus sequence was detected (Fig. 2A). This result confirms the direction of transcription of touR and places its transcriptional start at a position consistent with initiation of transcription from the −35, −10 promoter.

FIG. 2.

Mapping of the 5′-mRNA start of the touR gene (A) and of the tou operon (B). Primer extension analyses were performed as described in Materials and Methods. The primer extension products were run next to the sequence reactions performed on pFP3038 (A) and pPP4062 (B). To the right of each panel, an expanded view of the nucleotide sequence surrounding the transcriptional start site (+1) is shown.

Effector range of TouR.

Since in P. putida Paw340(pFB1112), ToMO expression is inducible by both toluene and o-cresol, whereas the primary structure of the A domain of TouR is more similar to that of DmpR than to that of XylR or TbuT, we investigated the TouR responsiveness to compounds able to induce ToMO activity.

The inducer range of ToMO was determined by assaying ToMO activity in P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cells exposed to different aromatic compounds. It was observed that toluene and o-xylene, which are the first substrates of the catabolic pathway, induced low ToMO activity levels (6.4 and 1.4 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1, respectively), whereas their corresponding monohydroxylated catabolic intermediates promoted a higher response (12 and 6.3 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1 for m-cresol and 2,3-DMP, respectively). The best inducer of ToMO activity was o-cresol (14 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1). However, since both toluene and o-xylene are ToMO substrates, no clear conclusion could be drawn about the actual efficiency of the two compounds to act as TouR effectors.

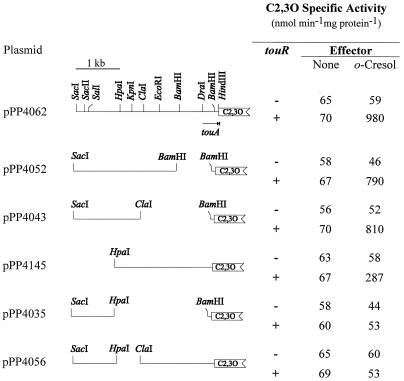

A reporter system was developed to study the TouR effectors in the absence of possible transformation by ToMO. From pFB1112, a 3.5-kb SacI-HindIII fragment, partially overlapping the first ToMO gene (touA) (coordinates 14 to 17.5 in Fig. 1) was cloned immediately upstream from a C2,3O reporter gene. The plasmid obtained, named pPP4062 (for the map, see Fig. 3), was transformed into P. putida PaW340(pFP3028) cells, and C2,3O activity was measured after exposure to hydrocarbons or phenols. The data (Table 2) confirmed the presence of a cognate TouR-responsive promoter(s) within the cloned fragment and showed that toluene and o-xylene could not act as TouR effectors, whereas all of the phenolic compounds tested, even those not derived from toluene and o-xylene, could induce high C2,3O activity levels. Among the phenolic compounds tested, monomethylated phenols turned out to be more efficient effectors than the dimethylated ones. Thus, consistent with the high degree of similarity detected between the A domains of TouR and DmpR, the TouR effector range was demonstrated to be more similar to that of regulators which control phenol catabolism than to that of regulators that control methylbenzene catabolism.

FIG. 3.

Deletion analysis of the putative ToMO promoter region. Portions of the putative ToMO promoter region were cloned upstream from the C2,3O reporter gene as described in Materials and Methods. The arrow represents the location of the incomplete touA ORF. C2,3O specific activity was measured in P. putida PaW340 cells carrying the pPP4062 derivatives shown in trans (+) or not (−) with touR, cloned in pFB3028, and grown in the presence (o-cresol) or absence (none) of the effector. A minimum of three independent experiments (variation within 10%) were performed for each strain; results from representative assays are shown.

TABLE 2.

Effector range of TouR

| Effector | C2,3O sp act (nmol min−1 mg of protein−1)a |

|---|---|

| None | 70 |

| o-Xylene | 58 |

| Toluene | 62 |

| 2,5-DMP | 395 |

| 2,4-DMP | 412 |

| 3,4-DMP | 424 |

| 2,3-DMP | 496 |

| p-Cresol | 532 |

| m-Cresol | 726 |

| o-Cresol | 980 |

C2,3O specific activity, expressed from the PToMO promoter fused to the C2,3O-encoding gene, was measured in P. putida PaW340(pPP4062) cells carrying touR in trans upon exposure to the indicated compounds. A minimum of three independent experiments (variation within 10%) were performed for each compound; results from representative assays are shown.

Identification of the ToMO promoter.

To identify the ToMO promoter region, the reporter system (pPP4062) described above was used. A series of deletions were carried out inside the 3.5-kb SacI-HindIII fragment cloned upstream from the reporter gene. The new recombinant plasmids were then transformed in P. putida PaW340 cells carrying touR (pFP3028) in trans, and the C2,3O activity was measured after exposure to o-cresol (Fig. 3). P. putida PaW340 cells carrying touR and the plasmid pPP4052 or pPP4043 retained the ability to respond to o-cresol, whereas in cells carrying the plasmid pPP4145, the activation of the reporter gene was strongly compromised, but not totally abolished. This suggested that the HpaI site is located in a critical region of the TouR-responsive promoter. In cells carrying the plasmids pPP4035 and pPP4056, the regulated expression of the reporter gene was completely lost, thus confirming the crucial role played by the region surrounding the HpaI site in regulating the expression of the reporter gene. A putative promoter could thus be mapped about 2 kb upstream from the ATG initiation codon of the first gene (4) coding for the ToMO enzymatic complex.

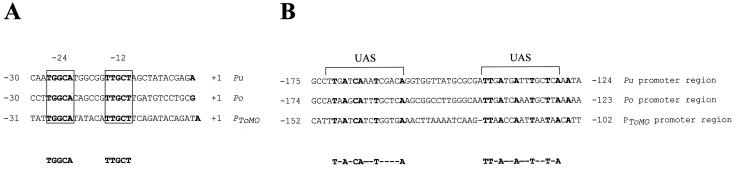

The 2-kb region upstream from touA was completely sequenced. Close to the HpaI restriction site, a region shown to be essential for the expression of the reporter gene, a putative ς54-dependent −24 TGGC, −12 TTGC promoter, was identified. Seventy-seven base pairs upstream from the putative −24 consensus sequence, two 15-bp repeats, highly homologous to the UASs recognized by several transcriptional activators of the catabolic pathway belonging to the NtrC family, were detected (Fig. 4). Two putative ORFs (orf1 and orf2 in Fig. 1) of unknown function were detected between the ToMO promoter and the first ToMO structural gene, touA.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of the ToMO promoter region. (A) DNA sequence alignment of the ς54-dependent promoter sequences of the xyl upper operon (Pu) (23), the dmp operon (Po) (40), and the tou operon (PToMO). The −24 and −12 sequences within the consensus sequence are boxed and labeled accordingly. The transcription starts are shown in boldface. (B) DNA sequence alignment of the palindromic regions (UASs) upstream of the promoters mentioned above. Nucleotides conserved in all three sequences are shown in boldface. The consensus sequences established from the comparison of the regions within and upstream of the Pu, Po, and PToMO operons are displayed below each alignment. Gaps, indicated by dashes, were introduced to maximize homology.

To identify the in vivo transcriptional start of tou transcript, primer extension analysis was performed with RNA isolated from o-cresol-induced P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cells. By using the oligonucleotide EXT1PT (see Materials and Methods), a single band, corresponding to an A residue located 13 nt downstream from the −12 consensus sequence was detected (Fig. 2B). This result places the start of the TouR-mediated operon transcript at a position consistent with initiation of transcription from the −24, −12 promoter.

Northern analyses.

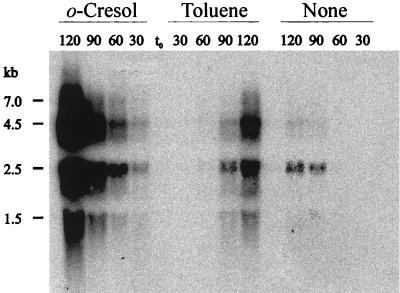

Since TouR was shown to be unable to recognize o-xylene and toluene as effectors, the ability of the two hydrocarbons to induce ToMO activity in PaW340(pFB1112) cells could be explained by hypothesizing that they were transformed into their corresponding monohydroxylated catabolic intermediates by virtue of a basal ToMO activity. To test this hypothesis, Northern analysis was carried out. RNA was extracted from P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cells not exposed or exposed to either o-cresol or toluene for different times. The presence of tou transcript(s) was detected by using touA as the probe (Fig. 5). In o-cresol-induced cells, a transcript whose size was consistent with the dimension of the entire tou operon (7 kb) was detectable. Major transcripts, which displayed lower molecular weight and suggested that the tou operon mRNA might be processed, were detectable after 30 min of exposure. In contrast, tou transcripts appeared in toluene-induced cells only 90 min after the addition of the inducer. In uninduced P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cell samples collected after 30 and 60 min of incubation, ToMO transcripts were undetectable, but low levels of ToMO transcription were observed in samples collected after 90 min, indicating that transcription of tou structural genes may occur in the absence of inducers. These data strongly suggest that, in the presence of toluene, ToMO activity may contribute to switching on its own transcription by converting the hydrocarbon into the actual TouR effectors. The delay in the appearance of ToMO transcripts in toluene-induced samples is consistent with this hypothesis.

FIG. 5.

Northern analysis of the ToMO transcripts. RNA was extracted from P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cells not exposed (none) or exposed to either toluene or o-cresol. Samples were collected at 30-min intervals (shown at the top) after addition of the inducer (t0). From each sample, 20 μg of RNA was analyzed by gel electrophoresis and probed with the touA gene to detect the ToMO transcripts.

DISCUSSION

The ToMO cloned from P. stutzeri OX1 was found to be regulated and inducible by toluene and o-xylene and their phenolic derivatives. A regulatory gene, designated touR, whose product positively controlled ToMO expression, was mapped downstream from and in the same direction of transcription of the tou structural genes (4).

Although this organization resembles the one described for the tbu genes coding for toluene-3-monooxygenase in B. pickettii PKO1 and the regulatory gene tbuT (5, 6), in P. stutzeri OX1, an additional ORF, orfA (Fig. 1), putatively coding for a transposase (4) is located on the opposite strand between touF and touR. Moreover, the regulatory circuits of the B. pickettii and the P. stutzeri systems appear to be very different. In the B. pickettii system, tbuT expression is driven by read-through transcription from the tbuA1 cognate promoter (5). In contrast, a rho-independent terminator was detected, downstream from touF, in the P. stutzeri tou gene cluster (4). This terminator could block read-through transcription. Indeed, as demonstrated here, touR is transcribed from a typical ς70 promoter. However, compared with the promoter regions of other regulatory genes of catabolic pathways, the touR promoter region displayed a peculiar feature. In xylR and dmpR, the ATG codon lies immediately downstream from the −35, −10 consensus promoter sequences (15, 40). In contrast, the translation start of touR lies 211 nt downstream from the determined transcriptional start. The analysis of the sequence between the touR +1 and its ATG did not reveal any significant homology to known catabolic regulatory genes. The functional significance of this region is unclear.

Based on polypeptide sequence comparison, TouR appeared to belong to the subfamily of NtrC-like regulators that positively control methylbenzene (XylR) and phenol (DmpR) catabolic pathways. These regulators bind to specific DNA sequences (UASs) and activate transcription from ς54-dependent promoters (17, 40). A TouR-responsive promoter (PToMO) was mapped approximately 2 kb upstream from touA, which is the first gene of the six structural genes coding for the subunits of ToMO (4). As expected, PToMO showed the typical −24 (GG), −12 (GC) consensus sequences of ς54-dependent promoters and putative UASs.

Between the PToMO promoter and touA, a 2-kb DNA region is present, where two putative ORFs were detected. Although this region was not further analyzed, the two putative ORFs are clearly inessential for the enzyme activity, as demonstrated by the ToMO activity levels measured in E. coli cells carrying a plasmid missing both of them (pBZ1260) (3, 4). In this respect, the tou upper operon resembled the pWW0 xyl upper operon, in which two genes, xylUW, not essential for xylene catabolism were mapped between the Pu promoter and the genes coding for the catabolic enzymes (42). A similar organization was also observed in the DNA region cloned from Pseudomonas mendocina PKR1, in which the tmo genes, coding for toluene-4-monoxygenase, are preceded by two ORFs of unknown function (44). However, the two ORFs detected in P. stutzeri did not show any homology to known sequences.

Interestingly, compared with the other NtrC-like catabolic regulators, TouR was found to be more similar to proteins which regulate phenol catabolism, like DmpR and PhhR, than to those which control methylbenzene catabolism, like XylR or TbuT. Besides the amino acid sequence, TouR and DmpR also showed similarities with regard to their effector range. In fact, the effector range of TouR consisted essentially of mono- and dimethylphenols and thus appears to be very similar to that of DmpR (39). This was not surprising, considering that the A domains of TouR and DmpR, which are believed to confer specificity, are highly similar. To the contrary, the inability of o-xylene and toluene to act as TouR effectors was less expected, considering that TouR regulates the expression of genes involved in the degradation of these compounds. Other known regulators of toluene catabolism, such as XylR, TbuT, and TbmR, recognize toluene as a strong effector. Phenols are not recognized by XylR (12, 39), but they interact very weakly with TbuT and TbmR (5, 18, 22). Thus, the specificity of TouR contrasts with that of other regulators of toluene degradation pathways. To the best of our knowledge, TouR is the first characterized hydrocarbon-degradation-controlling NtrC-like regulator that recognizes phenols as the sole effectors.

In its ability to recognize intermediates of the catabolic pathway, but not the primary substrates, as effectors, TouR resembles some regulators belonging to the LysR family of transcriptional activators, such as CatR, ClcR, and NahR (25, 36). In particular, NahR activates the transcription of both the nah (naphthalene degradation) and the sal (salicylate degradation) operons in the presence of salicylate, an intermediate of naphthalene catabolism. Low-level transcription and translation of the nah operon allow naphthalene to be slowly converted to salicylate, which then triggers the NahR-mediated transcription of both operons (35). A similar model can be proposed for the regulation of the P. stutzeri OX1 tou operon. In P. putida PaW340 cells carrying pFB1112, low levels of ToMO activity may slowly convert the hydrocarbons into the corresponding phenols. The phenols interact with TouR, which then promotes ToMO transcription. In this way, a cascade effect is established, which leads to increased synthesis of the monooxygenase. Considering that ς54-dependent promoters are not known to display basal transcription activity, the P. stutzeri system appears particularly interesting. Moreover, it is worth noting that in uninduced P. putida PaW340(pFB1112) cells, ToMO transcripts appeared only after 90 min of incubation, and their levels seem to increase with time. To the best of our knowledge, these features have not been described in any other ς54-dependent catabolic operon. Further experiments are in progress to elucidate this phenomenon both in the recombinant P. putida (pFB1112) strain and in the wild-type P. stutzeri OX1 strain.

Comparison between TouR and the other NtrC-like regulators of toluene degradative pathways supports the hypothesis of an independent evolution of regulatory proteins and circuits (9). According to the hypothesis of evolutionary recruitment of a preexisting regulatory gene for the expression of novel catabolic pathways (12), our data strongly suggest that TouR might have been recruited from a catabolic gene cluster different from the ToMO one, likely from a dmp-like operon or, at least, a gene cluster involved in phenol catabolism. It thus seems that even very similar catabolic operons may be controlled by distinct regulators following different schemes, even though the regulatory proteins likely act in a similar manner. This seems to be the case for the tou and the tbu gene clusters, which, although highly similar in organization and coded functions (4, 6), are regulated in a different way by very different regulators. It is thus reasonable to hypothesize that these two toluene monooxygenase-coding operons underwent distinctly different evolutions, at least with regard to their regulation. This hypothesis is also supported by the differences detected in touR and tbuT expression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (Rome), grant no. 97.01028.PF49 of the Target Project on Environmental Biotechnology, and by the Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (Rome) under the Programma di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale, contract “Characterisation of biodegradative enzymatic systems: oxidases and oxygenases” of P.B.

We are grateful to E. Coloubret and R. Macchi for collaboration on the experimental work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggi G, Barbieri P, Galli E, Tollari S. Isolation of a Pseudomonas stutzeri strain that degrades o-xylene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2129–2132. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2129-2132.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertoni G, Bolognese F, Galli E, Barbieri P. Cloning of the genes for and characterization of the early stages of toluene and o-xylene catabolism in Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3704–3711. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3704-3711.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertoni G, Martino M, Galli E, Barbieri P. Analysis of the gene cluster encoding toluene/o-xylene monooxygenase from Pseudomonas stutzeri OX1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3626–3632. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3626-3632.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne A M, Olsen R H. Cascade regulation of the toluene-3-monooxygenase operon (tbuA1UBVA2C) of Burkholderia pickettii PKO1: role of the tbuA1 promoter (PtbuA1) in the expression of its cognate activator, TbuT. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6327–6337. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6327-6337.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne A M, Kukor J J, Olsen R H. Sequence analysis of the gene cluster encoding toluene-3-monooxygenase from Pseudomonas pickettii PKO1. Gene. 1995;154:65–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00844-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collado-Vides J, Magasanik B, Gralla J D. Control site location and transcriptional regulation in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:371–394. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.371-394.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado A, Ramos J L. Genetic evidence for activation of the positive transcriptional regulator XylR, a member of the NtrC family of regulators, by effector binding. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8059–8062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Lorenzo V, Pérez-Martin J. Regulatory noise in prokaryotic promoters: how bacteria learn to respond to novel environmental signals. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1177–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devereux J, Haeberly P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6125–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández S, Shingler V, de Lorenzo V. Cross-regulation by XylR and DmpR activators of Pseudomonas putida suggests that transcriptional control of biodegradative operons evolves independently of catabolic genes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5052–5058. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.5052-5058.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin F C H, Williams P A. Construction of a partial diploid for the degradative pathway encoded by the TOL plasmid (pWW0) from Pseudomonas putida mt-2: evidence for a positive nature of the regulation by the xylR gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1980;177:321–328. doi: 10.1007/BF00267445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen J B, Olsen R H. Isolation of large bacterial plasmids and characterization of the P2 incompatibility group plasmids pMG1 and pMG5. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:227–238. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.1.227-238.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Determination of the transcription initiation site and identification of the protein product of the regulatory gene xylR for xyl operons on the TOL plasmid. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:863–869. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.863-869.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye S, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Nucleotide sequence of the regulatory gene xylR of the TOL plasmid from Pseudomonas putida. Gene. 1988;66:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inouye S, Gomada M, Sangodkar U M, Nakazawa A, Nakazawa T. Upstream regulatory sequence for transcriptional activator XylR in the first operon of xylene metabolism on the TOL plasmid. J Mol Biol. 1990;216:251–260. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80317-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson G R, Olsen R H. Multiple pathways for toluene degradation in Burkholderia sp. strain JS150. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4047–4052. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4047-4052.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn M, Kolter R, Thomas C M, Figurski D, Meyer R, Remaut E, Helinski D R. Plasmid cloning vehicles derived from plasmid ColE1, F, RK6 and RK2. Methods Enzymol. 1979;68:268–280. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)68019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kustu S, North A K, Weiss D S. Prokaryotic transcriptional enhancers and enhancer-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:397–342. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90163-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kustu S, Santero E, Keener J, Popham D, Weiss D. Expression of ς54 (ntrA)-dependent genes is probably united by a common mechanism. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:367–376. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.3.367-376.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leahy J G, Johnson G R, Olsen R H. Cross-regulation of toluene monooxygenases by the transcriptional activators TbmR and TbuT. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3736–3739. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3736-3739.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marques S, Ramos J L. Transcriptional control of the Pseudomonas putida TOL plasmid catabolic pathways. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:923–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin R W. Rapid colorimetric estimation of phenol. Anal Chem. 1949;21:1419–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFall S M, Chugani S A, Chakrabarty A M. Transcriptional activation of the catechol and chlorocatechol operons: variations on the theme. Gene. 1998;223:257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morett E, Segovia L. The ς54 bacterial enhancer-binding protein family: mechanism of action and phylogenetic relationship of their functional domains. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6067–6074. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6067-6074.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ng L C, Poh C L, Shingler V. Aromatic effector activation of the NtrC-like transcriptional regulator PhhR limits the catabolic potential of the (methyl)phenol degradative pathway it controls. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1485–1490. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.6.1485-1490.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng L C, O’Neill E, Shingler V. Genetic evidence for interdomain regulation of the phenol-responsive ς54-dependent activator DmpR. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17281–17286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.North A K, Klose K E, Stedman K M, Kustu S. Prokaryotic enhancer-binding proteins reflect eukaryote-like modularity: the puzzle of nitrogen regulatory protein C. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4267–4273. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4267-4273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nozaki M, Kotani S, Ono K, Seno S. Metapyrocatechase. Substrate specificity and mode of ring fission. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;220:213–223. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(70)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez-Martin J, De Lorenzo V. In vitro activities of an N-truncated form of XylR, a ς54-dependent transcriptional activator of Pseudomonas putida. J Mol Biol. 1996;258:575–587. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polissi A, Bertoni G, Acquati F, Dehò G. Cloning and transposon vectors derived from satellite bacteriophage P4 for genetic manipulation of Pseudomonas and other gram-negative bacteria. Plasmid. 1992;28:101–114. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(92)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schell M A. Transcriptional control of the nah and sal hydrocarbon-degradation operons by the nahR gene product. Gene. 1985;36:301–309. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schell M A. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:597–626. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shingler V. Signal sensing by ς54-dependent regulators: derepression as a control mechanism. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:409–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.388920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shingler V, Pavel H. Direct regulation of the ATPase activity of the transcriptional activator DmpR by aromatic compounds. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shingler V, Moore T. Sensing of aromatic compounds by the DmpR transcriptional activator of phenol-catabolizing Pseudomonas sp. strain CF600. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1555–1560. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1555-1560.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shingler V, Bartilson M, Moore T. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the positive regulator (DmpR) of the phenol catabolic pathway encoded by pVI150 and identification of DmpR as a member of the NtrC family of transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1596–1604. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1596-1604.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staskawicz B, Dahlbeck D, Keen N, Napoli C. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race 0 and race 1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5789–5794. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5789-5794.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams P A, Shaw L M, Pitt C W, Vrecl M. XylUW, two genes at the start of the upper pathway operon of TOL plasmid pWW0, appear to play no essential part in determining its catabolic phenotype. Microbiology. 1997;143:101–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vector and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yen K, Karl M R, Blatt L M, Simon M J, Winter R B, Fausset P R, Lu H S, Harcourt A A, Chen K K. Cloning and characterization of a Pseudomonas mendocina KR1 gene cluster encoding toluene-4-monooxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5315–5327. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5315-5327.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]