Abstract

Objectives:

The purpose of this study is to establish a novel, reproducible technique to obtain the BIC area (BICA) between zygomatic implants and zygomatic bone based on post-operative cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images. Three-dimensional (3D) image registration and segmentation were used to eliminate the effect of metal-induced artifacts of zygomatic implants.

Methods:

An ex-vivo study was included to verify the feasibility of the new method. Then, the radiographic bone-to-implant contact (rBIC) of 143 implants was measured in a total of 50 patients. To obtain the BICA of zygomatic implants and the zygomatic bone, several steps were necessary, including image preprocessing of CBCT scans, identification of the position of zygomatic implants, registration, and segmentation of pre- and post-operative CBCT images, and 3D reconstruction of models. The conventional two-dimensional (2D) linear rBIC (rBICc) measurement method with post-operative CBCT images was chosen as a comparison.

Results:

The mean values of rBIC and rBICc were 15.08 ± 5.92 mm and 14.77 ± 5.14 mm, respectively. A statistically significant correlation was observed between rBIC and rBICc values ( =0.86, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions:

This study proposed a standardized, repeatable, noninvasive technique to quantify the rBIC of post-operative zygomatic implants in 3D terms. This technique is comparable to conventional 2D linear measurements and seems to be more reliable than these conventional measurements; thus, this method could serve as a valuable tool in the performance of clinical research protocols.

Keywords: Bone-to-implant contact, zygomatic implants, atrophic edentulous maxilla, post-operative radiographic bone-to-implant contact, CBCT imaging

Introduction

With a long-term survival rate of 97.72±1.06%, zygomatic implants have gradually become a reliable choice for patients with atrophic maxillae. 1 In addition, zygomatic implants make immediate loading possible in edentulous patients, which presents a unique and overwhelming advantage compared to conventional methods. However, immediate loading may increase the occurrence of micromovement, 2 which may lead to osseointegration failure.

Bone-to-implant contact (BIC) was first described in 1913 by Greenfield. 3 By means of “contact-osseointegration”, the healing cascade occurs so that implants attain secondary stability. 4,5 Traditionally, BIC is termed the proportion of mineralized bone tissue from the surface of implants based on histomorphometry. 6 This means that when clinicians need to quantify BIC, a biopsy of the implant with the surrounding tissue is indispensable. However, it is important to point out that from a clinicians’ point of view, this method of measuring BIC is inapplicable in that this approach is invasive. To cope with this issue, many authors use imaging data, such as computed radiography (CR) periapical radiographs with parallel techniques and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), to evaluate the distance from the apex of the implant to the most coronal bone that is in direct contact with the implant, which is called radiographic BIC (rBIC). 7–9 As mentioned by Hausmann in 2000, CR periapical radiographs are reliable for implant measurement because the implant itself provides the means of correction. Moreover, the advantage of CBCT is that CBCT allows clinicians to visually identify the marginal bone level (MBL) 10 and have an acceptable correlation with histologic measurements. 11,12

However, titanium dental implants, especially zygomatic implants, which are much larger than conventional implants, can cause severe streaking artifacts and shading artifacts due to their high attenuation of X-rays. Therefore, clinicians prefer CR periapical radiography to CBCT in daily clinical practice to measure the post-operative rBIC because the MBL of conventional implants is relatively regular, whereas CBCT inevitably results in a considerable number of metal-induced artifacts, 13 such as blooming of the implant with enlargements easily reaching 12–15% of the implant diameter. 14

Unfortunately, in regard to zygomatic implants, everything is different. First, a CR periapical radiograph cannot be taken because the zygomatic bone is not an intraoral site. Furthermore, the margin can only be roughly identified in CBCT images due to metal-induced artifacts. Even when the diameter of the zygomatic implant is measured after the operation, the boundary of the zygomatic implant is difficult to recognize, which leads to poor predictability, and the measurement becomes unrepeatable. Even worse, the shape of zygomatic bone is irregular and differs in every patient. Owing to the irregularity of the zygomatic bone, the bone margin “level” of zygomatic implants is more of “an irregular curve” than “a horizontal line”. Previous studies 15,16 have obtained the rBIC of zygomatic implants once a clear image of implants was visible. The rBIC measurements were the average values of one or more sections. However, the rBIC measurements of zygomatic implants differ from each other in different sectional areas in CT, and a clear image of implants is innumerable when you rotate the image an angle along the long axis of zygomatic implants. That is, the rBIC measurement of zygomatic implants hampers from the irregular bone margin level and urgently requires standardization.

Therefore, this study aimed to establish a novel, reproducible technique to measure the rBIC of zygomatic implants after surgery. This approach could eliminate the effect of metal-induced artifacts on post-operative CBCT images to the greatest extent.

Methods and materials

Patients

The study protocol was scrutinized by the Ethical Committee of the Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SH9H-2021-T237-1). All patients signed informed consent on the day of surgery.

From September 2016 to June 2021, a total of 50 patients with 143 zygomatic implants were enrolled in this study, one or two zygomatic implants were placed in one side. This study focused on patients with a severe deficiency of the maxillary alveolar ridge whose maxillary residual bone volume presented with Cawood & Howell Class IV, V or VI classification. Most patients were completely edentulous or partially edentulous with hopeless teeth. All patients underwent a CBCT scan during pre-operative preparation. The implant planning software Nobel Clinician (Nobel Biocare AB, Sweden) was utilized to place the zygomatic implants virtually. Then, patients underwent zygomatic implant surgery. The effective diameter of all zygomatic implants was 3.75 mm and the length was ranged from 45 to 52.5 mm. After surgery, all patients underwent a post-operative CBCT examination. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with anatomical abnormalities of the zygoma, including but not limited to patients with congenital edentulism; (2) patients with severe facial asymmetry in any condition; and (3) the CT images had insufficient visual fields or were blurred. Only images that contained complete and clear images of the maxillary and zygomatic regions were included in this study.

CBCT standardization

CBCT images were acquired from the supraorbital edge to the border of the mandible of the participants. The voxel size was 0.2 mm, and the manufacturer’s recommended settings of 80 kV and 5 mA (i-Cat, Imaging Sciences International, LLC, Hatfield, Pennsylvania) or 96 kV and 5.6 mA (Planmeca ProMax 3D, Helsinki, Finland) were employed. All CBCT data were saved in Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format.

An ex-vivo study

To verify the feasibility of the new method, three 3D printing model skulls were used for physical measurements to compare the error between the actual BICA and the measured values. Before implant placement, image acquisition was performed for all samples by using CBCT devices. Six zygomatic implants were placed in both side of three skulls and the contact margin between the zygomatic implant and the zygomatic bone was supposed to be clearly visible, tracing the margin using a marker pen (Figure 1). After implant placement, a post-operative CBCT was performed for the measurement of the new method. Then, the zygomatic implant was screwed out. Using a topological approach, the margin was traced on a grid paper to obtain the contact area between the zygomatic implant and the zygomatic bone (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The contact margin was traced by a marker pen (red marker). Then, the zygomatic implant was extracted, and the contact margin curve was rubbed on a piece of grid paper.

Figure 2.

The rubbing of the contact margin was traced by a marker pen on the grid paper.

Imaging analysis

This measurement technique was based on the concept of the first mean value theorem for definite integrals in advanced mathematics called the “First Fundamental Theorem of Calculus”. If is a Riemann-integrable function on a close interval , when , the mean value of is as follows: . This means that the mean value of is the area of on divided by the length of .

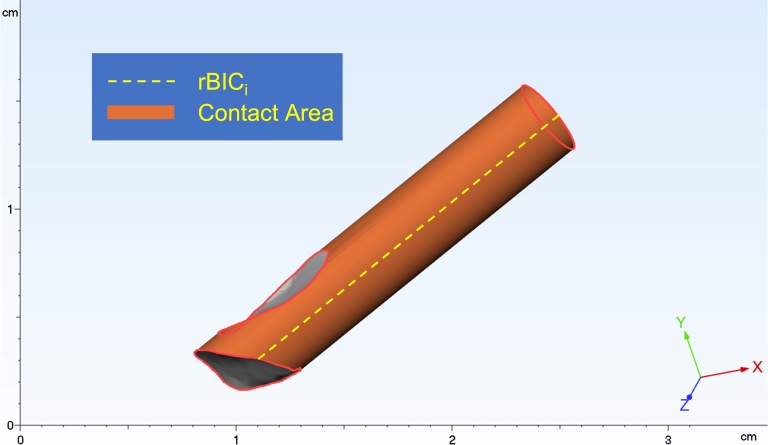

To apply this concept in the measurements of rBIC, the zygomatic implant was divided into indefinite parts along the axis of the zygomatic implant, and every part was called rBICi. The mean value of rBIC was the area of BICA between the zygomatic implant and the zygomatic bone divided by the circumference of the zygomatic implant (Figure 3). In all, in this study, the length of is the circumference of the zygomatic implant and the area of on is the area of BICA.

Figure 3.

This image depicts the interface between the zygomatic implant and the zygomatic bone (orange); this surface can be segmented into countless rBICi (yellow dashed line) regions. rBIC, radiographic BIC.

Therefore, the most critical problem in this study was the measurement of the area of BICA. The concrete steps taken are described below.

Image pre-processing for pre-operative CBCT

To reconstruct the skull from the CBCT data, the region of interest (ROI) was first labeled using Mimics Research 20.0 (Materialise’s interactive medical image control system, Materialise NV, Belgium) software to perform the following three semiautomatic steps. (1) The threshold was set as 250 HU, which was the default value for bone. As shown in the picture below (Figure 4A), the morphological structure of the zygomatic bone was clearly recognized, but due to the cancellous bone cavities, part of the ROI was unselected and needed fine-tuning. (2) The marking tool was used to fill the cavities (Figure 4B). (3) After labeling, the marching cubes algorithm 17 was applied to obtain a high-accuracy 3D model of the skull exported in STereoLithography (STL) format.

Figure 4.

The green label shows the zygomatic bone once the threshold was set (A). The blue label indicates a cavity of cancellous bone filled semiautomatically (B).

Image pre-processing for post-operative CBCT

The virtual zygomatic implant constructed in the software was always a simulation model with screw thread. In daily rBIC measurements, the effect of screw thread was not considered; hence, this study established a cylinder zygomatic implant model for measurement (Figure 5). A model with a length of 52.5 mm (the longest zygomatic implant available) and a diameter of 3.75 mm was established in coDiagnostiX PRODUCER 10.4 (Dental wings GmbH, Germany). Because the apex of the zygomatic implant was conical, though the model was unable to simulate this narrowing shape, all zygomatic implants were divided into two categories in the post-operative CBCT analysis depending on whether the apex of zygomatic implants was completely wrapped by the zygomatic bone (Figure 6A and B).

Figure 5.

The diameter was set as 3.75 mm, and the top & height was set as 52.5 mm using the tool “Implant Designer” in the coDiagnostiX implant planning software. Then, the new model was published to the implant database.

Figure 6.

The yellow line shows the border line of the zygomatic bone. As shown above, the apex of the zygomatic implant was completely wrapped by the zygomatic bone but seemed to be partially wrapped on the cylinder model (the blue line) (A). That problem did not occur when zygomatic implants were punched through the zygomatic bone (B). To correct this error, the study divided post-operative implants into two types according to whether the apex was completely wrapped so that the error (the red part) could be compensated for in subsequent steps.

The cylinder model was aligned with the zygomatic implant in the post-operative CBCT images semi-automatically using the function of the implant-centered tool. In that case, the influence of metal-induced artifacts was eliminated, and the precise position of the post-operative zygomatic implant was obtained.

Image alignment and registration

The metal-induced artifacts of zygomatic implants were emanative, which made the image blurry; therefore, it was difficult to recognize the margin of the zygomatic bone. To completely erase the effect of metal-induced artifacts, this study first performed registration between post- and pre-operative CBCT images automatically. After the above steps were completed, we finally gained the exact position of post-operative zygomatic implants on pre-operative CBCT images. The contact area of the cylinder model aligned, and the pre-operative CBCT presented as the BICA of the post-operative zygomatic implants and the zygomatic bone. Finally, the cylinder models were exported in STL format under the pre-operative CBCT coordinate system.

Image segmentation

To procure the intersection of the model of pre-operative CBCT and the cylinder models, the Visualization Toolkit (VTK) module, 18 vtkBooleanOperationPolyDataFilter class, was used. More specifically, the intersection of the zygomatic implants and the zygomatic bone was computed by bool operation and was labeled as the part of zygomatic implants drilled in the zygomatic bone during surgery. The bool operation is like the operational rules of set theory in three-dimensional (3D) space (“and”, “or”, “not” operational rules). The surface of this part (excluding the top and bottom area) was selected as the BICA of the zygomatic implants and the zygomatic bone (rBIC area). Every cylinder model was then exported in STL format as a contact part and a non-contact part.

rBIC measurements

After the above procedures were performed, there was a 3D model of the pre-operative CBCT images for each patient, and the zygomatic implants were divided into two parts under the same coordinate system (Figure 7). To identify the BICA and calculate the area of rBIC automatically, 3-matic Research 13.0 (Materialise NV, Belgium) was utilized. The 3D models were imported, and the contact area was marked. For the zygomatic implants completely wrapped by the zygomatic bone, the error was compensated for. The area of the marked surface was calculated automatically (Figure 8). The mean rBIC we were interested in was calculated by dividing these data divided by the circumference of the cylinder model.

Figure 7.

As shown in the image, the models (the 3D reconstruction model of the skull and virtual zygomatic implants) were imported into the 3-matic software. Every zygomatic implant was separated into two parts (red: contact area and green: non-contact area). 3D, three-dimensional.

Figure 8.

Using the marking tool, the contact area (orange: marked area) was selected. If the zygomatic implant was the type completely wrapped by the zygomatic bone, the apex surface was selected together. The software was capable of computing the marked area (the highlighted line in the bottom of the right corner).

Conventional method

The conventional method to measure rBIC was chosen for comparison in this study. Although the rBIC would never be perfectly consistent between the two methods, the overall trend was expected to be uniform. This study measured four data points in both the coronal section and median sagittal section (Figure 9A and B). In addition, the rBICc was the average of the four data points. Due to metal-induced artifacts, the margin of the zygomatic bone was determined by constantly adjusting the layer being viewed depending on the experience of the clinician.

Figure 9.

Using the function of the implant-centered tool, the section was adjusted to (A) and (B). The distance was measured on both the facial side and the temporal side.

Statistical analysis

All statistical data were analyzed by SPSS Statistics (SPSS v. 26.0, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). The correlation of rBIC and rBICc was determined by linear analysis. Pearson’s coefficient ( ) was calculated by SPSS 26.0. The significance level was p < 0.05.

Results

Error between the actual value and measured value

The actual value and measured value of 6 zygomatic implants are listed in Table 1. The mean linear error between the actual value and measured value is −0.18 mm and all linear errors are within 1 mm.

Table 1.

Actual values and measured values of six zygomatic implants placed in three model skulls

| Actual value (mm2) | Measured value (mm2) | Linear error (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 231 | 229.1966 | 0.15 |

| 2 | 257 | 264.3566 | −0.62 |

| 3 | 221 | 223.6769 | −0.23 |

| 4 | 233.5 | 232.0302 | 0.12 |

| 5 | 214.5 | 219.2890 | −0.41 |

| 6 | 289 | 290.2945 | −0.11 |

| Mean value | 241 | 243.1406 | −0.18 |

Patient demographics

50 patients (males = 22, females = 28; mean age = 50.68±12.74 years; age range: 20–75 years; median age: 53 years) with 143 zygomatic implants were included in this study. Of 2 patients placed 1 zygomatic implant, 25 placed 2 zygomatic implants, 1 placed 3 zygomatic implants, and 22 placed 4 zygomatic implants.

Values and statistical analysis of rBIC and rBICc

The mean value, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median of rBIC and rBICc are listed in Table 2. ICC revealed excellent intraexaminer agreements for both examiners 1 (ICC = 0.998, p < 0.0001) and 2 (ICC = 0.996, p < 0.0001). Likewise, interexaminer agreement was excellent (ICC = 0.998, p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of rBIC and rBICc values

| rBIC (mm) | rBICc (mm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 15.08 | 14.77 |

| Standard deviation | 5.92 | 5.14 |

| Minimum | 5.56 | 5.93 |

| Maximum | 41.66 | 32.15 |

| Median | 13.67 | 14.38 |

rBIC, radiographic BIC.

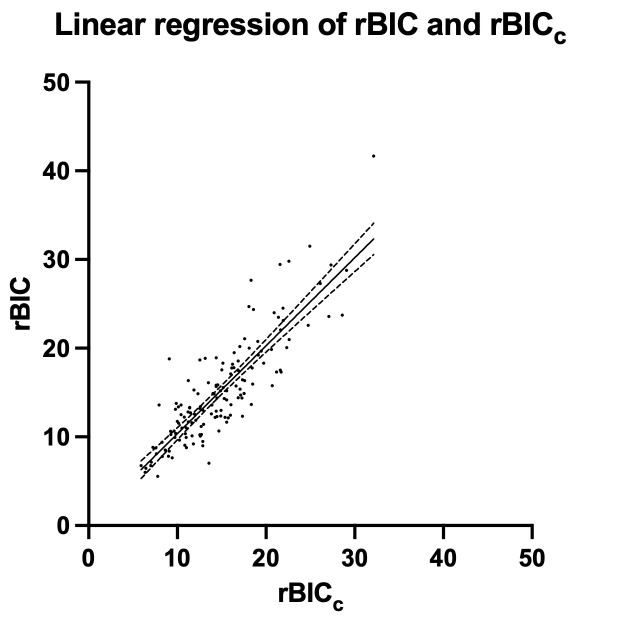

Correlation of rBIC and rBICc values

A statistically significant correlation was observed between rBIC and rBICc values ( =0.86, p < 0.0001). Linear regression of rBIC and rBICc values is shown in Figure 10. The equation of rBIC and rBICc was . The Pearson’s correlation coefficient indicated that the linear trends of rBIC and rBICc were significantly correlated.

Figure 10.

This graph shows the linear regression of rBIC and rBICc, including 95% confidence bands of the best-fit line. Residual errors were distributed normally. rBIC, radiographic BIC.

Discussion

In 2008, the measurement of zygomatic implant length was first established by N Pena, 19 non-metallic radiopaque markers were used to determine the entry and exit site for 10 dry human crania. The linear measurement of zygomatic implant was quantified by the best coronal CT slides chosen by an experienced dental radiologist.

The area of the zygomatic implant surface in contact with the zygomatic bone determines the BIC. It is well acknowledged that the length of the BIC is a crucial factor in determining the success and survival rate of implants. 20 The rBIC of zygomatic implant has been widely used in the past 10 years, and the measurement of rBIC of zygomatic implant has been retained in 2D terms, 15,16,21–26 which is widely accepted. Almost all studies 15,16,21–25 used the clear image in coronal slide to measure the linear rBIC, and one latest article 26 used the mean value of the coronal plane and sagittal plane, our study chose the conventional method based on the previous studies. However, since zygomatic implants are placed into a 3D anatomical structure, it seems more appropriate to calculate the rBIC in 3D terms than in 2D terms.

A previous investigation 27 calculated the sufficiency of zygomatic bone volume for virtual zygomatic implants engaged by manually drawing the implants layer by layer. As stated by Stoppie et al’s study, 28 a layer of metal artifacts around an implant was evident between the inserted implant and bone in CT images. Moreover, the great metal-induced artifacts that post-operative zygomatic implants produce make it difficult to segment the zygomatic implants and the zygomatic bone, let alone draw the implant. To prevent the problem of metal-induced artifacts, in a previous model study, 29 bone specimens and dental implants were scanned separately by micro-CT so that the 3D models of artificial bone and dental implants could be created individually. Similar to the previous study, our study separated zygomatic implants and zygomatic bone based on pre- and post-operative CBCT images. In our study, the measurement of volume or area was feasible, but we preferred area to volume because the contact area is the direct performance of BIC, not the bone we drilled then removed. To overcome this important clinical issue that remains unresolved by previous studies in the scientific literature, using unions and intersections, our team skillfully avoided the inclusion of metal-induced artifacts.

The data from our study are comparable to the study performed by Balshi et al, who stated in their study that of 77 patients receiving 173 zygomatic implants, the mean rBIC was 15.3 ± 5.6 mm. Balshi et al mentioned that as little as 4.9 mm of zygomatic BIC can provide enough implant anchorage immediately. 15 For edentulous patients with atrophic maxilla, the anchorage provided by zygomatic implants is crucial for the foundation of an immediate loading prosthesis. In our study, the minimum rBIC was 5.56 mm, which is larger than the limitation. This suggested that the treatment of zygomatic implants seems to be a reliable alternative for edentulism.

Furthermore, we sincerely hope that this method can be applied to the study of the peri-implantitis, which the level of bone loss is irregular, similar to the situation of the zygomatic implants. Also, this method needs more operating time than conventional 2D measurement method and the clinicians should have a good command of several image processing software programs, so we hope to develop a new software including all functions above can be developed in the future.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of this study, a reproducible technique to quantify the rBIC of post-operative zygomatic implants without invasion was proposed. Compared to the 2D linear measurement, quantifying the area of BICA seems to be more repeatable and more reliable. Also, the results of 3D measurements are comparable to the 2D measurements. The assessment of rBIC after zygomatic implant insertion may provide quantitative and valuable information about the interaction between the zygomatic implants and the zygomatic bone, which contributes to a proper clinical decision of loading strategy.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: We acknowledge the grants of Clinical Research Plan of SHDC (SHDC2020CR3049B). We also acknowledge the awards of CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (Project No. 2019-I2M-5–037), “Multidisciplinary Team” Clinical Research Project of Ninth People’s Hospital affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University, School of Medicine (2017-1-005), Industry supporting program of Huangpu District (XK2020014), and the Integrated Fund Project of the Ninth People’s Hospital.

Disclosure of interest: The authors do not have any financial interests, either directly or indirectly, in the products or information listed in the paper.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT: Research data are not shared.

Contributor Information

Yuwei Gu, Email: yuweigu_9hospital@foxmail.com.

Dingzhong Zhang, Email: dzzhang96@sjtu.edu.cn.

Baoxin Tao, Email: taobx3314@sjtu.edu.cn.

Feng Wang, Email: diana_wangfeng@aliyun.com.

Xiaojun Chen, Email: xiaojunchen@sjtu.edu.cn.

Yiqun Wu, Email: yiqunwu@hotmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sales P-H, Gomes M-V, Oliveira-Neto O-B, de Lima F-J, Leão J-C. Quality assessment of systematic reviews regarding the effectiveness of zygomatic implants: an overview of systematic reviews. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2020; 25: e541–48. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stokholm R, Spin-Neto R, Nyengaard JR, Isidor F. Comparison of radiographic and histological assessment of peri-implant bone around oral implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 2016; 27: 782–86. doi: 10.1111/clr.12683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenfield, EJ. Implantation of artificial crown and bridge abutments. Dent Cosmos 1913; 55: 364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davies JE. Understanding peri-implant endosseous healing. J Dent Educ 2003; 67: 932–49. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2003.67.8.tb03681.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Puleo DA, Nanci A. Understanding and controlling the bone-implant interface. Biomaterials 1999; 20: 2311–21. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00160-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Donath K, Breuner G. A method for the study of undecalcified bones and teeth with attached soft tissues. The säge-schliff (sawing and grinding) technique. J Oral Pathol 1982; 11: 318–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1982.tb00172.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Isidor F. Clinical probing and radiographic assessment in relation to the histologic bone level at oral implants in monkeys. Clin Oral Implants Res 1997; 8: 255–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1997.080402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fritz ME, Jeffcoat MK, Reddy M, Koth D, Braswell LD, Malmquist J, et al. Implants in regenerated bone in a primate model. J Periodontol 2001; 72: 703–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ritter L, Elger MC, Rothamel D, Fienitz T, Zinser M, Schwarz F, et al. Accuracy of peri-implant bone evaluation using cone beam CT, digital intra-oral radiographs and histology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2014; 43(6): 20130088. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20130088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hausmann E. Radiographic and digital imaging in periodontal practice. J Periodontol 2000; 71: 497–503. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corpas L dos S, Jacobs R, Quirynen M, Huang Y, Naert I, Duyck J. Peri-implant bone tissue assessment by comparing the outcome of intra-oral radiograph and cone beam computed tomography analyses to the histological standard. Clin Oral Implants Res 2011; 22: 492–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.02029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernaerts A, Barbier L, Abeloos J, De Backer T, Bosmans F, Vanhoenacker FM, et al. Cone beam computed tomography imaging in dental implants: a primer for clinical radiologists. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2020; 24: 499–509. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1701496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Antila K, Lilja M, Kalke M. Segmentation of facial bone surfaces by patch growing from cone beam CT volumes. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2016; 45(8): 20150435. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20150435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vanderstuyft T, Tarce M, Sanaan B, Jacobs R, de Faria Vasconcelos K, Quirynen M. Inaccuracy of buccal bone thickness estimation on cone-beam CT due to implant blooming: an ex-vivo study. J Clin Periodontol 2019; 46: 1134–43. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balshi TJ, Wolfinger GJ, Shuscavage NJ, Balshi SF. Zygomatic bone-to-implant contact in 77 patients with partially or completely edentulous maxillas. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 70: 2065–69. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang F, Bornstein MM, Hung K, Fan S, Chen X, Huang W, et al. Application of real-time surgical navigation for Zygomatic implant insertion in patients with severely atrophic maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018; 76: 80–87: S0278-2391(17)31144-8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lorensen WE, Cline HE. Marching cubes: a high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. SIGGRAPH Comput Graph 1987; 21: 163–69. doi: 10.1145/37402.37422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schroeder W, Martin K, Lorensen B. The visualization toolkit. Kitware, ISBN 978-1-930934-19-1 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pena N, Campos PSF, de Almeida SM, Bóscolo FN. Determination of the length of zygomatic implants through computed tomography: establishing a protocol. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2008; 37: 453–57. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/16676031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Al-Nawas B, Wagner W. 7.19 Materials in Dental Implantology. In: Ducheyne P, ed. Comprehensive Biomaterials II. Elsevier; 2017., : ages [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aparicio C, Manresa C, Francisco K, Ouazzani W, Claros P, Potau JM, et al. The long-term use of zygomatic implants: a 10-year clinical and radiographic report. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2014; 16: 447–59. doi: 10.1111/cid.12007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aparicio C, Manresa C, Francisco K, Aparicio A, Nunes J, Claros P, et al. Zygomatic implants placed using the Zygomatic anatomy-guided approach versus the classical technique: a proposed system to report rhinosinusitis diagnosis. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2014; 16: 627–42. doi: 10.1111/cid.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pu L-F, Tang C-B, Shi W-B, Wang D-M, Wang Y-Q, Sun C, et al. Age-related changes in anatomic bases for the insertion of zygomatic implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 43: 1367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lombardo G, D’Agostino A, Trevisiol L, Romanelli MG, Mascellaro A, Gomez-Lira M, et al. Clinical, microbiologic and radiologic assessment of soft and hard tissues surrounding zygomatic implants: a retrospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016; 122: 537–46. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hung KF, Ai QY, Fan SC, Wang F, Huang W, Wu YQ. Measurement of the Zygomatic region for the optimal placement of quad Zygomatic implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2017; 19: 841–48. doi: 10.1111/cid.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang TY, Hsia YJ, Sung MY, Wu YT, Hsu PC. Three-dimensional measurement of radiographic bone-implant contact lengths of zygomatic implants in zygomatic bone: a retrospective study of 66 implants in 28 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; 50: 1100–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bertos Quílez J, Guijarro-Martínez R, Aboul-Hosn Centenero S, Hernández-Alfaro F. Virtual quad zygoma implant placement using cone beam computed tomography: sufficiency of malar bone volume, intraosseous implant length, and relationship to the sinus according to the degree of alveolar bone atrophy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018; 47: 252–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stoppie N, van der Waerden J-P, Jansen JA, Duyck J, Wevers M, Naert IE. Validation of microfocus computed tomography in the evaluation of bone implant specimens. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2005; 7: 87–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2005.tb00051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsu J-T, Wu AY-J, Fuh L-J, Huang H-L. Effects of implant length and 3D bone-to-implant contact on initial stabilities of dental implant: a microcomputed tomography study. BMC Oral Health 2017; 17(1): 132. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0422-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT: Research data are not shared.