Abstract

Introduction

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is an evolving problem with varied presentation. No definite treatment guidelines are available at present that may reduce rate of recurrence. Current evidence suggests a ductal pathology behind IGM, which leads to periductal mastitis, leakage and sinus/fistula formation. Thus, excision of the sinus/fistulous tract with en-bloc wide local excision (WLE) of the lesion could be curative. The objective of this study was to look for the basic aetiology of IGM and evaluate the effectiveness of WLE with total or partial duct excision as a curative approach.

Methods

An institutional prospective comparative study was conducted over 4 years (2015–2019), in which 59 cases of IGM were randomly divided into three groups. After necessary investigations, patients in group A received steroid therapy, those in group B received WLE and patients in group C received WLE with total or partial duct excision as the mode of treatment. Postoperative follow-up was between 6 months and 3 years.

Results

Histopathological examination (HPE) was found to be the most suitable diagnostic procedure. Patients in group B showed the highest rate of recurrence (73.6%), followed by group A (35.0%) and group C (5.0%). Patients in group C had a significantly lower chance of recurrence compared with both group A and group B (p < 0.05). HPE reports of excised ducts from patients in group C showed ductal disruption and leakage along with periductal granuloma in 70% of cases.

Conclusions

The presence of duct granuloma indicates the association of ductal pathology in IGM. IGM is therefore a disease of the mammary ducts and en-bloc duct excision is curative in non-responding cases.

Keywords: Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis, Aetiology, Surgery, Steroid, Wide local excision, Duct excision

Introduction

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is a relatively new entity in the breast subspeciality (Figures 1 and 2). Definite aetiological factors causing IGM are yet to be identified and some studies suggest an autoimmune origin for the disease.1–4 IGM is also found to be associated with hyperprolactinaemia during the postpartum period and drug-induced hyperprolactinaemia.5–7 Tuberculosis has often been identified as a major cause in low/mid socio-economic countries.2,4,8

Figure 1 .

Granulomatous mastitis with multiple sinus and underlying mass and the postoperative result

Figure 2 .

Granulomatous mastitis showing non-healing ulcer with underlying mass and the postoperative result

IGM presents with clinical and radiological features that often mimic malignancy and, as a result, delay its diagnosis. Because of its unknown aetiology and overlapping clinicoradiological features, selecting appropriate treatment for patients with IGM remains a clinical challenge. Delayed diagnosis coupled with improper therapies cause chronic changes in breast parenchyma and wider involvement of the breast, which is often more difficult to treat.

Very few studies are currently available on which treatment guidelines can be based. Treatment with wide local excision (WLE), steroids or other immunosuppressives has been advocated, but recurrence remains a major issue. Some studies hypothesise that ductal pathology leads to periductal mastitis and leakage.9–13 This periductal disease causes an inflammatory collection that ruptures and leads to sinus or fistulous formation. Thus, excision of sinus/fistulous tract with en-bloc wide local removal of the lesion has the potential to be a curative mode of treatment.

The aims of the study were to: (a) find out whether there is any ductal pathology involved in IGM; and (b) evaluate the effectiveness of total or partial duct excision along with WLE as curative treatment in recurrent IGM.

Methods

An institutional prospective observational study was conducted over a period of 4 years (December 2015 to December 2019). Before commencement, ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee.

After obtaining informed consent, patients with histopathologically proven granulomatous mastitis and recurrent disease were included in the study. For the purpose of this study, cases that presented with persistence of symptoms after conservative treatment for more than 6 months with antibiotics and/or steroids and prolactin inhibitors (eg, Cabergoline) for hyperprolactinemia were considered as recurrent disease.

Patients who presented with lump and recurrent breast abscess underwent open drainage or ultrasonography (USG)-guided aspiration. The pus was sent for culture and sensitivity, Gram staining, acid fast bacilli staining and BACTEC study. Biopsies were taken from the abscess cavity. These were sent for histopathological examination (HPE) and culture sensitivity studies to rule out tubercular or mycobacterium other than tuberculosis (MOTT) infection. In the case of patients presenting with sinus or non-healing ulcers without lump, incisional biopsies were taken and sent for HPE and bacteriological study for definite diagnosis. In patients with predominant breast mass, core biopsies were taken from the mass for the purpose of definite tissue diagnosis.

Cases with confirmed tuberculosis and MOTT infection were excluded from this study. Patients with disease involving multiple breast quadrants and those with autoimmune diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) were also excluded.

In total, 59 patients were included in the study. The selected patients were evaluated by triple assessment: USG was undertaken in all 59 patients, mammography in 11 cases, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the bilateral breast in 9 patients.

All 59 patients were randomly allocated to one of three groups (on a sequential basis). Group A underwent steroid therapy (20 patients), group B underwent WLE of the mass (19 patients) and group C underwent WLE of the clinically evident mass/sinus tract along with en-bloc total or partial duct excision (20 patients) (Figures 3 and 4). In group A, patients were given prednisolone at a dose of 30mg/day for 4 weeks primarily. Depending on the outcome and disease regression, this was continued up to 24 weeks.3 In the other groups (B and C), after surgical treatment, patients were not given steroid during the follow-up period of 6 months.

Figure 3 .

Allocation of selected patients into three treatment groups (n = 59)

Figure 4 .

Lactiferous duct showing the origin of the inflammation. The course of periductal progression leading to sinus formation is demonstrated. The dotted zone depicts the zone of curative resection.

After surgery (groups B and C), specimens from all cases were sent for histopathology and in patients in whom ductal excision was also performed (group C), ducts were evaluated by histopathological examination. All patients were followed up clinically and radiologically over a period of 6 months to 3 years after completion of treatment. During follow-up, significant clinical findings (eg, recurrent ulcer/sinus/abscess) and radiological features (eg, localised collection at operated site/features of recurrent mastitis) after a minimum of 6 months of treatment and/or follow-up were considered as recurrence. A chi-squared test was used to assess whether there was a significant difference in the risk of recurrence between these three groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

More than three-quarters of patients (n = 45, 76.3%) presented with IGM within 2 years of the birth of their most recent child and around 88.1% (n = 52) presented within 5 years. Of the patients, 35.6% (n = 21) had a previous history of oral contraceptive pill (OCP) intake, none had a history of smoking and 3.4% (n = 2) had a history of previous trauma to breast on the affected side.

All patients presented with one or two of the following features. Breast mass was the most common presenting symptom (n = 52, 88.1%), followed by sinus formation (n = 46, 77.9%) and chronic breast abscess (n = 22, 37.3%). Axillary lymphadenopathy (n = 21, 35.5%), peau d’orange (n = 4, 6.7%), persistent breast ulceration (n = 11, 18.5%) and nipple inversion (n = 8, 13.5%) were also encountered. The coexistence of two symptoms was found in 20 cases (33.9%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 .

Distribution of patients according to presenting feature (n=59) (multiple options)

In our patients, USG showed a hypoechoic or mixed echogenic mass with architectural distortion, diffuse skin thickening, fluid collection and axillary lymphadenopathy. USG misinterpreted the mass as malignant in 12 cases (20.3%) and as suspected malignancy in 5 cases (8.4%). These 17 cases were re-evaluated by mammogram and/or MRI. Mammogram and MRI reports were inconclusive in 36.4% (4 of 11) and 22.2% (2 of 9) of cases, respectively.

Histopathology was the most sensitive diagnostic method because non-caseating granuloma was found in all 59 patients (100%). Excised ducts from patients in group C were sent for HPE. Reports revealed ductal disruption and leakage along with periductal granuloma in 14 of the 20 patients (70.0%); 3 patients (15.0%) had significant inflammatory cells within the ducts.

On follow-up, 35.0% (n = 7) of patients in group A showed disease recurrence. In group B, 73.6% (n = 14) showed recurrence and in group C, recurrence was seen in one case (5.0%).

WLE as a single mode of treatment (group B) was associated with a significantly higher risk of recurrence when compared with steroid treatment (group A) [odds ratio (OR) 5.200, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.317–20.54]. Risk of recurrence was significantly lower in patients in whom both WLE and total duct excision was performed (group C) when compared with WLE alone (group B) (OR 0.019, 95% CI 0.002–0.179). In addition, there was a significant difference in the risk of recurrence in between group A and group C, the risk being lower in group C (OR 0.097, 95% CI 0.011–0.892) (Table 1).

Table 1 .

Association of recurrence with different treatment modalities (n=59)

| Treatment modality | Recurrence | Total | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurred | Did not recur | ||||

| Steroid | 7 | 13 | 20 | Reference | < 0.05 |

| WLE | 14 | 5 | 19 | 5.200 (1.317–20.54) | |

| WLE | 14 | 5 | 19 | Reference | < 0.05 |

| WLE+TDE | 1 | 19 | 20 | 0.019 (0.002–0.179) | |

| Steroid | 7 | 13 | 20 | Reference | < 0.05 |

| WLE+TDE | 1 | 19 | 20 | 0.097 (0.011–0.892) | |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio; TDE = total duct excision; WLE = wide local excision

Discussion

This study highlights sinus formation and indurated lumps as the commonest modes of presentation in IGM. Similar reports were found in some existing studies.12,14–17 As per our observation, radiological evaluation proved to be a poor diagnostic tool in the case of IGM. USG only shows heterogenous hypoechoic lesions and lymphadenopathy.3 Mammogram and MRI have limited roles in diagnosis, with the exception of differentiating between non-malignant and malignant lesions.3,15,18,19 In line with other work, this study emphasises that histopathological examination is required in every suspected case of IGM to reach a definite diagnosis.3,4,17,20,21

Understanding the pathogenesis of IGM is the cornerstone of treatment planning. Although a few studies suggest IGM to be of autoimmune origin,1–4 none of our patients had any known systemic autoimmune disease because such cases were excluded from this study. However, local inflammatory reaction seems to be the most important causative factor for IGM. The disease pathology starts as ductal dilation, likely related to pregnancy and postpartum breast changes. This is followed by leakage. Most of our patients (88.1%) presented within 5 years of the birth of their most recent child. Therefore, the disease can be related to ductal pathology, which is manifested after the lactational period.10,22 Ductal pathology due to inflammatory changes has also been reported by some studies. Retained milk proteins in the dilated ducts can produce local autoimmune inflammatory reactions, which might lead to granulomatous diseases of the breast.3,23 Cytokine release causes periductal parenchymal destruction, finally leading to single or multiple cutaneous sinus/fistulae.

The presence of non-caseating epithelioid granulomas is the hallmark of IGM. In developing countries, mycobacterium tuberculosis is often found to be associated with IGM. However, this can be ruled out by acid fast bacilli staining/BACTEC study and an absence of central caseation. The literature suggests that smoking and OCP intake are significantly associated with IGM.3 Around one-third of our patients had a history of OCP intake. However, none of our patients had a history of smoking, perhaps due to the low prevalence of women smokers in India compared with the West.24

Blind lumpectomy often has the worst outcome. In most circumstances, the recurrence is worse than the original presentation. Simple excision should therefore not be considered in the management of IGM. The use of steroids is based on the hypothesis that the disease has an autoimmune origin. Steroid usage is associated with a better outcome than lumpectomies, but has a poorer outcome than WLE with en-bloc total/partial duct excision, and is more unpredictable. Steroid use is further contraindicated in the presence of pus-discharging sinus and indurated mass with intralesional collections. The long-term side effects are often problematic for young women, although steroid use continues to have a role in predominantly lump-only lesions in the young age group. Treatment with methotrexate is another option for conservative management, but has limited evidence. The risk to benefit ratio of using methotrexate is also controversial in women of childbearing age.13

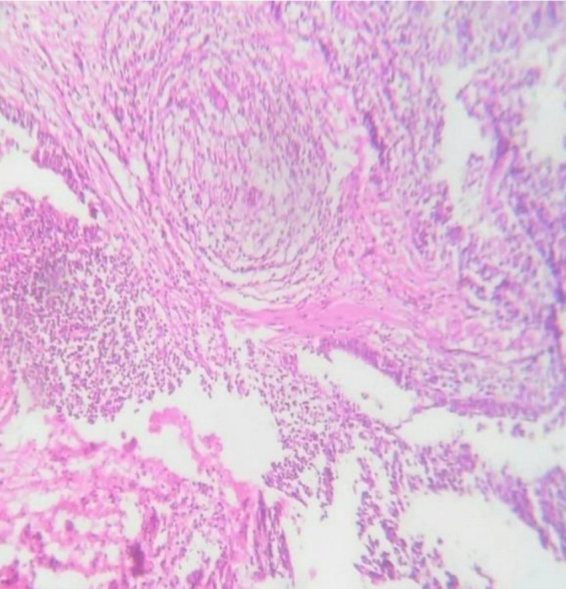

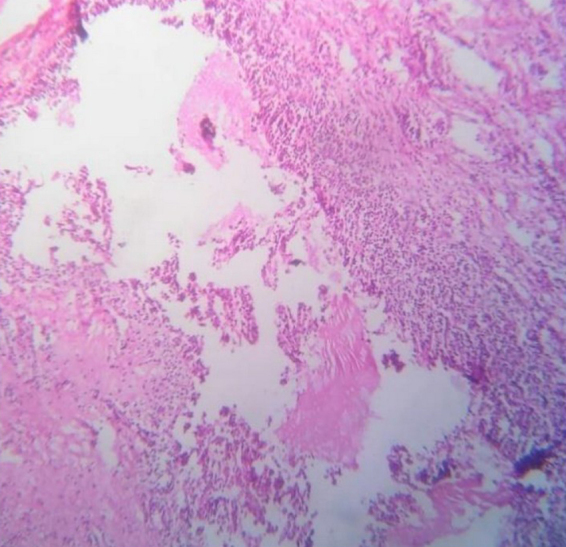

This study establishes the ‘ductal origin’ hypothesis of IGM. We found ductal disruption and periductal or intraductal granuloma in more than 70% of cases (Figures 6 and 7). The disease process as identified can be compared with sinus or fistula anywhere in the body, where complete excision of the sinus/fistulous tract is curative. Following the same principle, WLE of the mass along with total duct excision was carried out in patients enrolled in group C, who had the best and most predictable curative outcome compared with the other two groups (Figure 4). Mobilising the breast plate and apposing it after large volume resections can improve the cosmetic outcome in these patients.

Figure 6 .

Granuloma in relation to the large mammary duct

Figure 7 .

Large mammary duct infiltrated by mixed inflammatory cells

Multi-quadrant sinuses and fistulae remain a major surgical and medical challenge in the treatment of IGM. Duct excision can be a relative contraindication in individuals desirous of future lactation.

Conclusions

This study strengthens the claim for a ‘ductal origin’ of IGM, likely to be associated with recent onset hyperprolactinaemia-induced ductal dilation and local inflammation. WLE with en-bloc duct excision is associated with the best curative and cosmetic outcome in patients with recurrent disease not responding to conservative management.

References

- 1.Maffini F, Baldini F, Bassi Fet al. Systemic therapy as a first choice treatment for idiopathic granulomatous mastitis. J Cutan Pathol 2009; 36: 689–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gautier N, Lalonde L, Tran-Thanh Det al. Chronic granulomatous mastitis: imaging, pathology and management. Eur J Radiol 2013; 82: e165–e175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson JR, Dumitru D. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: presentation, investigation and management. Future Oncol Lond Engl 2016; 12: 1381–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghajanzadeh M, Hassanzadeh R, Alizadeh Sefat Set al. Granulomatous mastitis: presentations, diagnosis, treatment and outcome in 206 patients from the north of Iran. Breast Edinb Scotl 2015; 24: 456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolaev A, Blake CN, Carlson DL. Association between hyperprolactinemia and granulomatous mastitis. Breast J 2016; 22: 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khaffaf B, Knox F, Bundred NJ. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a 25-year experience. J Am Coll Surg 2008; 206: 269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor GB, Paviour SD, Musaad Set al. A clinicopathological review of 34 cases of inflammatory breast disease showing an association between corynebacteria infection and granulomatous mastitis. Pathology (Phila) 2003; 35: 109–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fayed WI, Soliman KE, Ahmed YHet al. Schematic algorithm for surgical treatment of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis using combined steroids and therapeutic mammoplasty techniques. Egypt J Surg 2019; 38: 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kok KYY, Telisinghe PU. Granulomatous mastitis: presentation, treatment and outcome in 43 patients. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel 2010; 8: 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hur SM, Cho DH, Lee SKet al. Experience of treatment of patients with granulomatous lobular mastitis. J Korean Surg Soc 2013; 85: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boufettal H, Essodegui F, Noun Met al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: a report of twenty cases. Diagn Interv Imaging 2012; 93: 586–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pluguez-Turull CW, Nanyes JE, Quintero CJet al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: manifestations at multimodality imaging and pitfalls. Radiographics 2018; 38: 330–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfrum A, Kümmel S, Theuerkauf Iet al. Granulomatous mastitis: A therapeutic and diagnostic challenge. Breast Care 2018; 13: 413–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazzio RT, Shah SS, Sandhu NP, Glazebrook KN. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: imaging update and review. Insights Imaging 2016; 7: 531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oztekin PS, Durhan G, Nercis Kosar Pet al. Imaging findings in patients with granulomatous mastitis. Iran J Radiol 2016; 13: e33900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen LJH, Peyvandi B, Klipfel Net al. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: imaging. Diagnosis, and Treatment. Am J Roentgenol 2009; 193: 574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurleyik G, Aktekin A, Aker Fet al. Medical and surgical treatment of idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis: a benign inflammatory disease mimicking invasive carcinoma. J Breast Cancer 2012; 15: 119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dursun M, Yilmaz S, Yahyayev Aet al. Multimodality imaging features of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: outcome of 12 years of experience. Radiol Med (Torino) 2012; 117: 529–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozturk M, Mavili E, Kahriman Get al. Granulomatous mastitis: radiological findings. Acta Radiol Stockh Swed 1987 2007; 48: 150–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiyak G, Dumlu EG, Kilinc Iet al. Management of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis: dilemmas in diagnosis and treatment. BMC Surg 2014; 14: 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2482-14-66 (cited 2020 March 9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6294038_Idiopathic_Granulomatous_Mastitis_A_Heterogeneous_Disease_with_Variable_Clinical_Presentation Idiopathic Granulomatous Mastitis: A Heterogeneous Disease with Variable Clinical Presentation [Internet]. ResearchGate. (cited February 2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Akcan A, Akyıldız H, Deneme MAet al. Granulomatous lobular mastitis: A complex diagnostic and therapeutic problem. World J Surg 2006; 30: 1403–1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0476-0 (cited 2020 March 9). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omranipour R, Mohammadi S-F, Samimi P. Idiopathic granulomatous lobular mastitis – report of 43 cases from Iran; introducing a preliminary clinical practice guideline. Breast Care 2013; 8: 439–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42580 atlas6.pdf [Internet]. (cited February 2023).