Abstract

Introduction

Gastrectomy remains the primary curative treatment modality for patients with gastric cancer. Concerns exist about offering surgery with a high associated morbidity and mortality to elderly patients. The study aimed to evaluate the long-term survival of patients with gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy comparing patients aged <70 years with patients aged ≥70 years.

Methods

Consecutive patients who underwent gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma with curative intent between January 2000 and December 2017 at a single centre were included. Patients were stratified by age with a cut-off of 70 years used to create two cohorts. Log rank test was used to compare overall survival and Cox multivariable regression used to identify predictors of long-term survival.

Results

During the study period, 959 patients underwent gastrectomy, 520 of whom (54%) were aged ≥70 years. Those aged <70 years had significantly lower American Society of Anesthesiologists grades (p<0.001) and were more likely to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy (39% vs 21%; p<0.001). Overall complication rate (p=0.001) and 30-day postoperative mortality (p=0.007) were lower in those aged <70 years. Long-term survival (median 54 vs 73 months; p<0.001) was also favourable in the younger cohort. Following adjustment for confounding variables, age ≥70 years remained a predictor of poorer long-term survival following gastrectomy (hazard ratio 1.35, 95% confidence interval 1.09, 1.67; p=0.006).

Conclusions

Low postoperative mortality and good long-term survival were demonstrated for both age groups following gastrectomy. Age ≥70 years was, however, associated with poorer outcomes. This should be regarded as important factor when counselling patients regarding treatment options.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Gastrectomy, Adenocarcinoma, Aged

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer death.1 Incidence is strongly related to age, with approximately 65% of new cases in the UK presenting in patients aged over 70 years.2 Although there have been steady increases in life expectancy over the past few decades,3 more than one-third of those living beyond the age of 70 years now have multiple chronic health conditions. This percentage increases further with advancing age.4 The incidence of gastric cancer has declined in the general population; however, it is rising among the elderly in some parts of the world. This is likely to be a result of this increased life expectancy.5 As such, more elderly and comorbid patients are now being diagnosed with the disease.

In patients with potentially curative gastric cancer, gastrectomy remains the definitive treatment modality. Despite improved outcomes over time, 30-day postoperative mortality remains high, ranging between 4.1% and 7.4% in recent studies.6–10 A number of risk factors for adverse postoperative outcomes have been suggested, particularly the influence of age and the associated prevalence of comorbidities in the elderly population.8,9

Improvements in outcomes have led to surgeons offering gastrectomy with curative intent to an increasing number of older patients. Some studies have even suggested that survival comparable with that in younger cohorts is achievable.11 However, the importance of advanced age as a risk factor, alongside markers of frailty and physical performance, must be duly considered. Strategies aimed at the reduction of postoperative morbidity and mortality may be of particular benefit in this higher risk patient group.

The aim of this study was to evaluate long-term outcomes in patients with gastric cancer who underwent surgery, comparing patients aged under 70 years with those aged 70 and over.

Methods

Patient population

A contemporaneously maintained database of consecutive patients with adenocarcinoma of the stomach, between January 2000 and June 2017, was reviewed. All patients who underwent total or subtotal gastrectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy with curative intent at the Northern Oesophagogastric Unit in Newcastle upon Tyne were included for analysis. A cut-off of age 70 years was chosen to define the elderly because this is a commonly reported threshold within the existing literature.9,12,13

Staging

All patients were discussed at a multidisciplinary team meeting and appropriate staging investigations were completed. These comprised endoscopy with biopsy and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis. In patients thought to have locally advanced disease, a staging laparoscopy was also performed. Endoscopic ultrasound and positron emission tomography CT were utilised in selected patients.

Treatment

Multiple adjuvant and neoadjuvant regimens were used in this patient cohort, determined by the standard of care and clinical trials recruiting at the time of treatment. Total or subtotal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection was performed within 4–8 weeks after completion of neoadjuvant therapy. Total gastrectomy was performed either due to diffuse-type disease or if the tumour’s proximity to the gastro-oesophageal junction did not allow the minimum of 5cm of clearance required for a subtotal gastrectomy.

Surgical technique

Resections were performed via an open approach with radical en bloc D2 lymphadenectomy in all cases. For total gastrectomy, a retrocolic oesophagojejunal anastomosis was formed using a circular stapling device to create an end-to-side anastomosis. The small bowel end was closed using a stapler before continuity was restored via a 45cm Roux limb with a two-layered continuous end-to-side hand-sewn jejunojejunal anastomosis. Subtotal gastrectomy involved the stomach being transected at an appropriate level with a stapling device before the Roux limb was formed as above. An end-to-side gastrojejunostomy was created in two layers via a hand-sewn anastomosis. Resectional and reconstruction phases are performed in this manner by all consultants and senior trainees in the department for both operations.

Histopathology

Following resection en bloc, specimens were dissected by the operating surgeon into respective lymph node stations. Reporting was carried out by specialist gastrointestinal pathologists with tumour type and differentiation, the depth of tumour infiltration and tumour regression all detailed according to the Mandard criteria.14 The total numbers of nodes from each anatomical location and any nodal metastases were recorded.15 Margin status for resections was considered according to longitudinal measurements. Also noted was the presence of extracapsular, lymphatic, venous and peri-neural invasion. Pathological stage was determined according to the eighth edition of the AJCC TNM staging system.16

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was overall survival, defined as time from surgery to last follow-up or death. Secondary outcomes were 30-day postoperative mortality and postoperative complications.

Definitions of complications

Complications following gastrectomy were defined as those that featured on the recent, internationally agreed, consensus definition list.17 The severity of these was then classified according to the Clavien–Dindo scoring system for postoperative complications.18 Anastomotic leak was defined as a full-thickness defect of the gastrointestinal tract involving an anastomosis formed intraoperatively. This was confirmed using either contrast swallow, CT scan or endoscopy.

Follow-up

During the first two years of follow-up, all patients were seen as outpatients at three- to six-month intervals. Following this, review was every six months or annually. After five years, follow-up was on a yearly basis for a total of 10 years. For the purposes of this study, follow-up was extended until June 2019, ensuring that the included patients had a minimal potential follow-up of 24 months.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were stratified by age at diagnosis (<70 vs ≥70 years). Categorical variables were compared using a chi-squared test and non-normally distributed data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Overall survival was estimated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and comparison was made between groups using the log-rank test. Inpatient deaths were included in analyses for overall survival. Multivariable analyses used Cox proportional hazards modelling to identify predictors of long-term survival. A p-value of <0.050 was considered to be statistically significant in all cases. Data analyses were performed using R Foundation Statistical software (R v. 3.2.2) with TableOne, ggplot2, Hmisc, Matchit and survival packages (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

During the study period, 959 patients underwent a total (42%) or subtotal (58%) gastrectomy, and 624 (65%) of them were male. The median age for the cohort was 71 years (range 24–93 years), 520 (54%) were aged ≥70 years. Across the more elderly group, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grades were significantly higher (p<0.001) with almost half of patients recorded as grade 3 or 4 (Table 1).

Table 1 .

Baseline demographics by age

| Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <70 | ≥70 | Overall | p value | |

| Number of patients | 439 (46) | 520 (54) | 959 | |

| Age* | 62.0 [13] | 76.0 [6] | 71 [13] | 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.180 | |||

| Male | 296 (67) | 328 (63) | 624 (65) | |

| Female | 143 (33) | 192 (37) | 335 (35) | |

| BMI* | 26 [6] | 25 [5] | 25 [6] | 0.013 |

| ASA grade | <0.001 | |||

| Grade 1 | 54 (12) | 14 (3) | 68 (7) | |

| Grade 2 | 232 (53) | 230 (44) | 462 (48) | |

| Grade 3 | 124 (28) | 238 (46) | 362 (38) | |

| Grade 4 | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | 11 (1) | |

| Unknown | 24 (5) | 32 (6) | 56 (6) | |

| Treatment modalities | <0.001 | |||

| NA chemotherapy + surgery | 170 (39) | 107 (21) | 277 (29) | |

| NA CRT + surgery | 2 (0) | 2 (0) | 4 (0) | |

| Surgery + adjuvant CRT | 5 (1) | 2 (0) | 7 (1) | |

| Surgery + adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy | 15 (3) | 6 (1) | 21 (2) | |

| Surgery only | 247 (56) | 403 (78) | 650 (68) | |

| Surgery type | <0.001 | |||

| Subtotal gastrectomy | 223 (51) | 333 (64) | 556 (58) | |

| Total gastrectomy | 216 (49) | 187 (36) | 403 (42) | |

| Overall clinical tumour staging | 0.894 | |||

| Stage 0 | 28 (6) | 35 (7) | 63 (7) | |

| Stage 1 | 83 (19) | 99 (19) | 182 (19) | |

| Stage 2 | 201 (46) | 242 (46) | 443 (46) | |

| Stage 3 | 109 (25) | 129 (25) | 238 (25) | |

| Stage 4 | 18 (4) | 15 (3) | 33 (3) | |

| Overall pathological tumour staging | 0.259 | |||

| Stage 0 | 13 (3) | 9 (2) | 22 (2) | |

| Stage 1 | 161 (37) | 184 (35) | 345 (36) | |

| Stage 2 | 134 (30) | 190 (37) | 324 (34) | |

| Stage 3 | 93 (21) | 108 (20) | 201 (21) | |

| Unknown | 38 (9) | 29 (6) | 67 (7) | |

| Tumour grade | 0.247 | |||

| Moderate | 173 (43) | 231 (48) | 404 (46) | |

| Poor | 209 (51) | 222 (46) | 431 (49) | |

| Unknown | 24 (6) | 26 (5) | 50 (6) | |

| Lymph nodes examined* | 29 [17] | 29 [18] | 29 [18] | 0.976 |

| R1 margin status | 32 (7) | 28 (5) | 60 (6) | 0.280 |

| Lymph node involvement | 234 (53) | 295 (57) | 529 (55) | 0.318 |

| Venous involvement | 179 (41) | 226 (43) | 405 (42) | 0.439 |

| Perineural involvement | 226 (51) | 233 (45) | 459 (48) | 0.046 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; CRT = chemoradiotherapy; NA = neoadjuvant

Values are shown as n (%) or median [interquartile range, Q3 minus Q1]

χ2 test for difference except *non-normally distributed data using Mann–Whitney U test

Treatment modalities

Among those aged ≥70 years, 36% underwent total gastrectomy, compared with 49% aged <70 years (p<0.001). On subgroup analysis, the median (interquartile range [IQR]) age was lower for those who underwent a total gastrectomy compared with a subtotal gastrectomy (72 [65, 78] vs 69 [62, 74] years). Patients also trended towards higher ASA grades in the subtotal gastrectomy group (Appendix 1a and 2a – available online).

Use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment modalities varied greatly between the older and younger cohorts (p<0.001; Table 1). Patients aged <70 years were more likely to receive neoadjuvant treatment (39% vs 21%); in almost all cases this was neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The younger cohort was also more likely to receive adjuvant treatment. As such, patients above the age of 70 were more likely to undergo surgery alone (78% vs 56%).

Clinical and pathological staging

The clinical staging of tumours was comparable between patients aged <70 and ≥70 years (p=0.894). In both cohorts, patients most frequently presented with stage 2 disease. Pathological tumour staging was comparable between age groups (p=0.259), with the majority of patients having pT1 or pT2 malignancies.

Histopathological findings

A higher percentage of patients aged <70 years had poorly differentiated tumours (51% vs 46%) but this difference did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.247).

A median of 29 (IQR 18) lymph nodes were examined across the total patient cohort. This figure was almost identical on comparison between those aged <70 and ≥70 years (p=0.976). Although a slightly higher percentage of older patients demonstrated lymph node involvement (57% vs 53%), this difference was again not statistically significant (p=0.318).

A R0 resection was completed in the vast majority of patients in both age groups (93% aged <70 years vs 95% aged ≥70 years). Rates of venous invasion (p=0.439) were also similar. More patients aged <70 years were noted to have perineural involvement (51% vs 45%; p=0.046).

Postoperative outcomes

Overall postoperative complication rate was higher in those aged ≥70 years (49% vs 38%; p=0.003) (Table 2). Complications in both age groups were most commonly of Clavien–Dindo grade I or II (31% aged <70 years vs 39% aged ≥70 years). A notably higher rate of grade III and above complications was seen among patients aged ≥70 years (11% vs 7%). Whereas the incidences of pulmonary complications and anastomotic leak were similar, cardiac complications were over twice as common in the older cohort (10% vs 4%). On subgroup analysis, according to the operation performed, overall complication rates were higher following total (53%) compared with subtotal (37%) gastrectomy. In each subgroup, those aged ≥70 years were at higher risk (both p=0.004). In particular, cardiac complications (16% vs 5%; p=0.040) and anastomotic leaks (17% vs 9%; p=0.040) were more common in more elderly patients following total gastrectomy. This trend was not observed in the subtotal gastrectomy cohort (Appendix 1b and 2b – available online).

Table 2 .

Postoperative outcomes by age

| Age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <70 | ≥70 | Overall | p value | |

| Length of stay* | 12 [7] | 14 [9] | 13 [8] | <0.001 |

| Critical care length of stay* | 0 [1] | 0 [2] | 0 [2] | 0.003 |

| Overall complications | 167 (38) | 255 (49) | 422 (44) | 0.003 |

| Clavien–Dindo grade I–II | 136 (31) | 200 (39) | 336 (35) | |

| Clavien–Dindo grade III | 12 (3) | 16 (3) | 28 (3) | |

| Clavien–Dindo grade IV | 15 (3) | 21 (4) | 36 (4) | |

| Clavien–Dindo grade V | 4 (1) | 18 (4) | 22 (2) | |

| Select complications | ||||

| Surgical site infection | 42 (10) | 40 (8) | 82 (9) | 0.358 |

| Pulmonary complications | 32 (7) | 49 (9) | 81 (8) | 0.286 |

| Cardiac complications | 17 (4) | 50 (10) | 67 (7) | 0.001 |

| Anastomotic leak | 27 (6) | 39 (8) | 66 (7) | 0.487 |

| Overall in-hospital mortality | 8 (2) | 26 (5) | 34 (4) | 0.013 |

| 30-Day postoperative mortality | 4 (1) | 20 (4) | 24 (3) | 0.007 |

Values are shown as n (%) or median with [interquartile range, Q3 minus Q1]

χ2 test for difference except *non-normally distributed data using Mann–Whitney U test

Patients aged ≥70 years also had significantly increased in-hospital mortality (p=0.013) with most of these deaths occurring in the 30-day postoperative period. Although mortality rates among those who had undergone subtotal gastrectomy were similar between age groups, total gastrectomy in patients aged ≥70 years was associated with a significantly increased in-hospital (p=0.020) and 30-day postoperative (p=0.009) mortality.

Overall survival

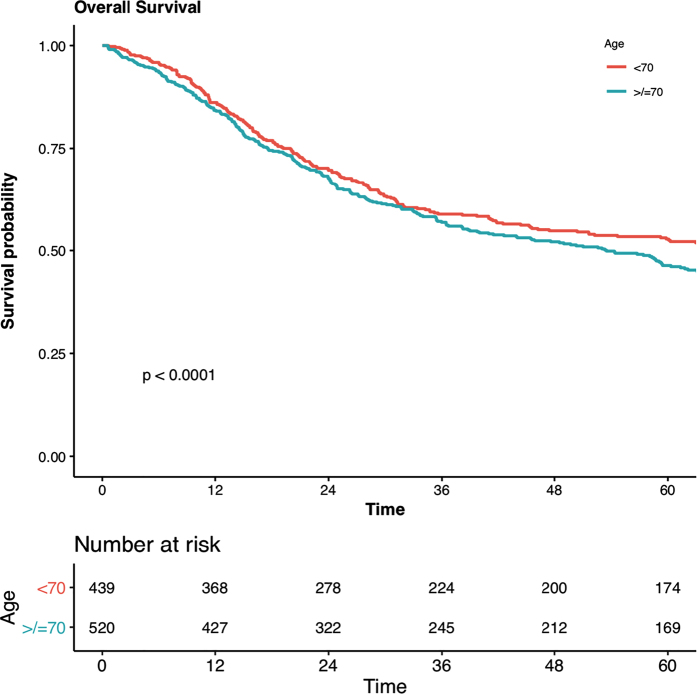

The median follow-up for the overall patient cohort was 59.2 months. Patients aged <70 years had a median long-term survival of 73.1 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 50.4, 93.3; Figure 1). Survival at 1, 3 and 5 years was 86%, 59% and 53%, respectively. This was a significantly improved overall survival when compared with those aged ≥70 years (median 53.5 months, 95% CI 40.0, 63.1; p<0.001). The proportions of elderly patients alive were similarly lower at 1 year (84%), 3 years (57%) and 5 years (46%).

Figure 1 .

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (<70 vs ≥70 years old) and number at risk for study cohort

On subgroup comparison of survival by pathological stage, comparable survival rates were noted between age groups in stage pT3 (p=0.17) and pT2 (p=0.075) malignancies. Among those staged pT1, however, significantly improved survival was evident in patients aged <70 years (Appendix 3 – available online).

After adjustment for confounding variables, age ≥70 years was confirmed as an adverse predictor of long-term survival following gastrectomy (hazard ratio [HR] 1.35, 95% CI 1.09, 1.67; p=0.006) (Table 3). Patients with higher ASA grades were also found to have an associated increased mortality risk (ASA 3: HR 1.23, 95% CI 0.80, 1.90; ASA 4: HR 2.07, 95% CI 0.76, 5.63) but this was not statistically significant following multivariable adjustment. Choice of treatment modality did not influence survival.

Table 3 .

Cox multivariable regression analysis of factors influencing overall survival following gastrectomy

| HR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| <70 years | 1.00 | |

| ≥70 years | 1.35 (1.09, 1.67) | 0.006 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.00 | |

| Male | 1.14 (0.93, 1.40) | 0.211 |

| BMI | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.004 |

| ASA grade | ||

| Grade 1 | 1.00 | |

| Grade 2 | 0.93 (0.61, 1.42) | 0.741 |

| Grade 3 | 1.23 (0.80, 1.90) | 0.351 |

| Grade 4 | 2.07 (0.76, 5.63) | 0.153 |

| ASA unknown | 1.05 (0.60, 1.86) | 0.854 |

| Operation year | ||

| 2000–2008 | 1.00 | |

| 2009–2017 | 0.96 (0.76, 1.21) | 0.738 |

| Treatment modalities | ||

| NA chemotherapy + surgery | 1.00 | |

| NA CRT + surgery | 0.49 (0.12, 2.00) | 0.320 |

| Surgery + adjuvant CRT | 1.21 (0.56, 2.63) | 0.632 |

| Surgery + adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy | 1.03 (0.53, 1.99) | 0.926 |

| Surgery only | 1.07 (0.83, 1.37) | 0.610 |

| Overall pathological stage | ||

| Stage 0 | 1.00 | |

| Stage 1 | 0.98 (0.28, 3.39) | 0.977 |

| Stage 2 | 1.78 (0.51, 6.22) | 0.363 |

| Stage 3 | 2.87 (0.82, 10.04) | 0.099 |

| Tumour grade | ||

| Moderate | 1.00 | |

| Poor | 1.31 (1.06, 1.61) | 0.011 |

| Unknown | 0.86 (0.49, 1.51) | 0.599 |

| Lymph nodes examined | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.007 |

| R1 margin status | 2.02 (1.43, 2.86) | <0.001 |

| Lymph node involvement | 1.30 (1.02, 1.64) | 0.032 |

| Venous involvement | 1.18 (0.94, 1.48) | 0.159 |

| Perineural involvement | 1.44 (1.14, 1.81) | 0.002 |

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; CRT = chemoradiotherapy; HR = hazard ratio; NA = neoadjuvant

Among histopathological findings, tumours graded as poorly differentiated were associated with decreased long-term survival (p=0.011). Tumours resected with positive margins were found to have the highest risk of adversely affecting survival (HR 2.02, 95% CI 1.43, 2.86; p<0.001). Lymph node or perineural involvement were also found to adversely affect patients’ survival (p=0.032 and p=0.002 respectively).

Discussion

This study demonstrated low postoperative mortality and good long-term survival following gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma. Although acceptable outcomes were seen across both age groups, significant differences were evident among our more elderly patient cohort. Patients aged ≥70 years were found to have a median survival following surgery of 54 months, whereas patients aged <70 years could expect to survive more than 18 months longer. There was also an increased risk of 30-day postoperative mortality and morbidity observed among the elderly population.

Although the incidence of gastric cancer has fallen by approximately 50% within the UK over the past 30 years, age remains a strong risk factor. Approximately 65% of those diagnosed in the UK are above the age of 70;2 a higher proportion than that seen in this study. This may suggest that a greater proportion of the more elderly cohort have been deemed not suitable for, or have opted against, gastrectomy. It may even be reflective of a higher rate of patients in this age group presenting with metastatic disease. As is seen in the wider population,4 older patients with gastric cancer tend towards having more comorbidities.19 Among this study cohort, almost 50% of these patients ≥70 years old were ASA grade 3 or 4. Because elderly patients appear to commonly be of poorer premorbid state, the potential role of preoperative optimisation (prehabilitation) should be considered of particular interest for this age group. Numerous clinical trials in this area are recruiting patients with oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma20–22 with much still to be learnt regarding this relatively new group of interventions. Optimum protocols for groups of patients, such as the elderly, or for particular operative procedures are yet to be established.

Age and comorbidity are undoubtedly important variables, and more detailed consideration of patient factors during treatment planning is likely to be of further benefit. Frailty is more commonly seen in the elderly population, but considerable variation in the degree of frailty has been observed even within this age group.23 A growing body of literature has highlighted frailty as an additional risk factor24 alongside sarcopenia,25 performance status and preoperative weight loss26 for patients undergoing gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Such variables may be captured by a comprehensive geriatric assessment and future research into the influence of age would benefit from their consideration. In addition, objective measures of preoperative fitness, such as cardiopulmonary exercise testing or the incremental shuttle walk test have been shown to strongly correlate with survival in patients who have undergone an oesophagogastric resection,27,28 thus indicating their value prior to multidisciplinary team decision-making.

Significant variations in the treatment modalities utilised were noted in the analyses. Total gastrectomy was performed significantly more frequently in patients aged <70 years (49% vs 36%). It could be postulated that a higher proportion of older patients had diffuse-type disease or proximal tumours; these data was unfortunately not available and intrinsic bias may instead be present owing to total gastrectomy being known to carry a greater postoperative risk.7 These findings concur with this higher risk, with increased rates of postoperative complications and mortality noted in more elderly patients following total gastrectomy. Conversely, mortality outcomes following subtotal gastrectomy were comparable between age groups.

Clinical practice regarding the use of oncological therapies in patients with gastric cancer has changed considerably over the study period. The evolution of care for patients with gastric cancer has trended away from unimodality surgery, as reported previously at this institution.29 In the majority of more contemporary cases of locally advanced cancer, chemotherapy was given as per the MAGIC regime;30 however, we note that the proportion of patients who received neoadjuvant is slightly lower than that reported by the National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit across similar periods.31–33 Younger patients in this study were more likely to receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, yet over half of those aged <70 years and over three-quarters of those ≥70 years underwent surgery alone. A recent national registry analysis from The Netherlands similarly found a considerable difference in the use of adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy when comparing patients by age group.9 However, far fewer patients in each age group underwent surgery alone when comparing their study population with this study (age <70: 20% vs 56%; age ≥70: 60% vs 78%). This disparity could be a due to a multitude of factors including patient preference, frailty or comorbidities that may preclude neoadjuvant treatment. An important difference to also note when comparing these two cohorts is the differences in tumour staging. Most patients in Nelen et al’s study had pT3 or pT4 disease (61%), whereas our study cohort contained a lot more patients with pT1 or pT2 disease (70%). The more advanced pathological staging of patients in the Dutch study is therefore more comparable with those from large randomised controlled trials, such as the FLOT34 and MAGIC30 trials, which demonstrated the benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with more locally advanced adenocarcinoma. In the current study patients were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in recent years, although factors such as poor renal function or concerns regarding frailty and possible preoperative deconditioning often precluded wider use, particularly among elderly patients. These findings do, however, highlight the possibility that elderly patients are more likely to receive suboptimal treatment. Further exploration of the shared decision-making model for adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies is certainly required in this patient group.

The 30-day postoperative mortality rate of 3% demonstrated within this cohort compares favourably within the existing western literature.6–11 These outcomes reflect all patients undergoing a radical lymphadenectomy, as evidenced by high lymph node yield; a procedure traditionally feared to be associated with greater postoperative morbidity and mortality,35 and thus not always the standard of care across some other comparator case series. This study’s results did, however, highlight a fourfold increase in postoperative mortality among patients aged ≥70 years. Nelen et al observed similarly increased mortality following multivariable adjustment, but found age not to be a predictor of postoperative death.9 Results from a large Italian cohort study revealed a postoperative mortality rate of only 3% with similarly no difference between age groups36 although the majority of other papers have identified higher mortality among more elderly patients.11,37–39 The evidence for advanced age being associated with postoperative morbidity is more conclusive9,38,40 and the current study’s results certainly supported this. In particular, results from this cohort demonstrated a more than twofold increase in cardiac complications among more elderly patients (10% vs 4%) which is in keeping with findings from previous comparator research.11,41 In particular, cardiac complications and anastomotic leaks were more frequently observed, where no such differences were noted in those who had undergone a subtotal gastrectomy. Considering this increased risk, the question must be raised as to whether further preoperative investigation, such as echocardiograms, may be of benefit for patients in this age group.

This study’s results showed significantly improved overall survival in patients aged <70 years (73.1 vs 53.5 months; p<0.001). This compared favourably, across both age groups, with a recent population-based analysis of the Netherland’s Cancer Registry. Brenkman et al identified a median overall survival of 58 months in patients aged <75 years39 with survival less than half among their more elderly patient group (27 months). The negative influence of advanced age on overall survival is noted consistently throughout the existing literature.11,13,37,38,42 However, when attempting to isolate the influence of age following adjustment of other confounding variables, the findings become less clear. The current study showed age ≥70 years to be a predictor of poorer long-term survival following gastrectomy (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.09, 1.67) but this contrasts with some previous research. Despite survival being lower among elderly cohorts, adjustment for other prognostic factors, such as comorbidities, previously clarified age to not be a risk factor.36,42 A large propensity-score matched analysis by Zhang et al did support the current study’s results; however, their regression did not include data on patients’ comorbid status, thus limiting conclusions that can be drawn.43 Zhang et al also used the age of 50 years as a cut-off, which is considerably lower than that used in the wider literature. The variety of ages used to split cohorts is certainly a limitation for the comparisons that can be drawn, with no consensus age for what defines an elderly patient agreed.

This study describes contemporaneously collected data from a single tertiary institution and thus the associated potential for bias could be considered a limitation. As discussed previously, there are characteristic differences between our study cohort and comparator previous publications. As such, these findings may also not be generalisable for other patient populations. The extensive experience demonstrated by this large patient cohort, combined with the standardised approach to preoperative treatment planning and surgical technique, is conversely a strength of the study that allowed a thorough investigation of the impact of age among this UK-based patient population. The evolution in treatment for patients with gastric adenocarcinoma is evident across our study period, and future developments in both oncological and surgical therapies will undoubtedly merit ongoing research into improving care for these patients. Although the proportion of gastrectomies performed with minimally invasive surgical techniques remains low in the UK, we anticipate that the growing evidence base for improved perioperative outcomes via this44 or even robotic approaches45 will lead to a greater uptake over the coming years.

Conclusion

This study highlights that excellent postoperative and long-term survival outcomes are achievable in patients aged ≥70 years. Elderly patients must, however, be counselled regarding the increased risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality, and the poorer long-term survival following gastrectomy when compared with younger patients. This, alongside other clinicopathological features and markers of physical performance, can help in the shared decision-making process during treatment planning for gastric adenocarcinoma.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram Iet al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Research UK. 2020. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/stomach-cancer/incidence#heading-One Stomach cancer incidence statistics [Internet]. . Available from: (cited February 2023).

- 3.Bongaarts J. How long will we live? Popul Dev Rev 2006; 32: 605–628. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office for National Statistics. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13#what-are-the-implications-of-living-longer-for-health-services Living longer - how our population is changing and why it matters. ; 1–53. (cited February 2023).

- 5.Ahn HS, Lee HJ, Yoo MWet al. Changes in clinicopathological features and survival after gastrectomy for gastric cancer over a 20-year period. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papenfuss WA, Kukar M, Oxenberg Jet al. Morbidity and mortality associated with gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2014; 21: 3008–3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin AN, Das D, Turretine FEet al. Morbidity and mortality after gastrectomy: identification of modifiable risk factors. J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 20: 1554–1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Gestel YRBM, Lemmens VEPP, De Hingh IHJTet al. Influence of comorbidity and age on 1-, 2-, and 3-month postoperative mortality rates in gastrointestinal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20: 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelen SD, Bosscha K, Lemmens VEPPet al. Morbidity and mortality according to age following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2018; 105: 1163–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norero E, Vega EA, Diaz Cet al. Improvement in postoperative mortality in elective gastrectomy for gastric cancer: analysis of predictive factors in 1066 patients from a single centre. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017; 43: 1330–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gretschel S, Estevez-Schwarz L, Hünerbein Met al. Gastric cancer surgery in elderly patients. World J Surg 2006; 30: 1468–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saif MW, Makrilia N, Zalonis Aet al. Gastric cancer in the elderly: An overview. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010; 36: 709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang YX, Deng JY, Guo HHet al. Characteristics and prognosis of gastric cancer in patients aged ≥70 years. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19: 6568–6578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandard A-M, Dalibard F, Mandard J-Cet al. Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer 1994; 73: 2680–2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin M, Greene F, Edge Set al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more ‘personalized’ approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baiocchi GL, Giacopuzzi S, Marrelli Det al. International consensus on a complications list after gastrectomy for cancer. Gastric Cancer 2019; 22: 172–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clavien P-A, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML V. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koppert LB, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Louwman MWJet al. Comparison of comorbidity prevalence in oesophageal and gastric carcinoma patients: A population-based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 16: 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Roy B, Pereira B, Bouteloup Cet al. Effect of prehabilitation in gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma: study protocol of a multicentric, randomised, control trial-the PREHAB study. BMJ Open 2016; 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chmelo J, Phillips AW, Greystoke Aet al. A feasibility study to investigate the utility of a home-based exercise intervention during and after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for oesophago-gastric cancer-the ChemoFit study protocol. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2020; 6: 4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen S, Brown V, Prabhu Pet al. A randomised controlled trial to assess whether prehabilitation improves fitness in patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment prior to oesophagogastric cancer surgery: study protocol. BMJ Open 2018; 8: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmar KL, Law J, Carter Bet al. Frailty in older patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. Ann Surg 2021; 273: 709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim G, Min SH, Won Yet al. Frailty in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Dig Surg 2021; 38: 66–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamarajah SK, Bundred J, Tan BHL. Body composition assessment and sarcopenia in patients with gastric cancer : a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer 2018; 22: 10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pujara D, Mansfield P, Ajani Jet al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in patients with gastric and gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma undergoing gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol 2015 Dec; 112: 883–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whibley J, Peters CJ, Halliday LJet al. Poor performance in incremental shuttle walk and cardiopulmonary exercise testing predicts poor overall survival for patients undergoing esophago-gastric resection. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018; 44: 594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chmelo J, Khaw RA, Sinclair RCFet al. Does cardiopulmonary testing help predict long-term survival after esophagectomy? Ann Surg Oncol 2021; 28: 7291–7297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin SM, Kamarajah SK, Navidi Met al. Evolution of gastrectomy for cancer over 30-years: changes in presentation, management, and outcomes. Surgery 2021; 170: 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SPet al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer david. N Engl J Med 2006; 335: 11–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit Project Team. National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit 2009. 2009.

- 31.National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit Project Team. National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit 2013. 2013. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB11093/clin-audi-supp-prog-oeso-gast-2013-rep.pdf (cited February 2023).

- 32.National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit Project Team. National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer Audit 2016. 2016.

- 33.Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Pauligk Cet al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): a randomised, phase2/3 trial. Lancet 2019; 393: 1948–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cuschieri A, Fayers P, Fielding Jet al. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: preliminary results of the MRC randomised controlled surgical trial. Lancet 1996; 347: 995–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orsenigo E, Tomajer V, Di PSet al. Impact of age on postoperative outcomes in 1118 gastric cancer patients undergoing surgical treatment. Gastric Cancer 2007; 10: 39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeshita H, Ichikawa D, Komatsu Set al. Surgical outcomes of gastrectomy for elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg 2013; 37: 2891–2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujiwara Y, Fukuda S, Tsujie Met al. Effects of age on survival and morbidity in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017; 9: 257–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenkman HJF, Goense L, Brosens LAet al. A high lymph node yield is associated with prolonged survival in elderly patients undergoing curative gastrectomy for cancer: A Dutch population-based cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 2213–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin HS, Oh SJ, Suh BJ. Factors related to morbidity in elderly gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomies. J Gastric Cancer 2014; 14: 173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee KG, Lee HJ, Yang JYet al. Risk factors associated with complication following gastrectomy for gastric cancer: retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data based on the Clavien-Dindo system. J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 18: 1269–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dittmar Y, Rauchfuss F, Götz Met al. Impact of clinical and pathohistological characteristics on the incidence of recurrence and survival in elderly patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg 2012; 36: 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Gan L, Xu MDet al. The prognostic value of age in non-metastatic gastric cancer after gastrectomy: A retrospective study in the U.S. and China. J Cancer 2018; 9: 1188–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Straatman J, van der Wielen N, Cuesta MAet al. Minimally invasive versus open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcomes and completeness of resection : surgical techniques in gastric cancer. World J Surg 2016; 40: 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ojima T, Nakamura M, Hayata Ket al. Short-term outcomes of robotic gastrectomy vs laparoscopic gastrectomy for patients with gastric cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 2021; 156: 954–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamarajah SK, Griffiths EAet al. Robotic techniques in esophagogastric cancer surgery: an assessment of short- and long-term clinical outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol 2021; 156: doi: 10.1245/s10434-021-11082-y. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]