Abstract

Crowding in Emergency Departments (EDs) has emerged as a global public health crisis. Current literature has identified causes and the potential harms of crowding in recent years. The way crowding is measured has also been the source of emerging literature and debate. We aimed to synthesize the current literature of the causes, harms, and measures of crowding in emergency departments around the world. The review is guided by the current PRIOR statement, and involved Pubmed, Medline, and Embase searches for eligible systematic reviews. A risk of bias and quality assessment were performed for each review, and the results were synthesized into a narrative overview. A total of 13 systematic reviews were identified, each targeting the measures, causes, and harms of crowding in global emergency departments. Key among the results is that the measures of crowding were heterogeneous, even in geographically proximate areas, and that temporal measures are being utilized more frequently. It was identified that many measures are associated with crowding, and the literature would benefit from standardization of these metrics to promote improvement efforts and the generalization of research conclusions. The major causes of crowding were grouped into patient, staff, and system-level factors; with the most important factor identified as outpatient boarding. The harms of crowding, impacting patients, healthcare staff, and healthcare spending, highlight the importance of addressing crowding. This overview was intended to synthesize the current literature on crowding for relevant stakeholders, to assist with advocacy and solution-based decision making.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11739-023-03239-2.

Keywords: Emergency Department, Crowding, Overcrowding, Emergency Room, Quality Assurance

Introduction

Emergency Department (ED) crowding presents a global public health crisis and results from the inability of health care systems to provide adequate service, leaving the ED to serve as the safety valve for dysfunction or insufficient resources. ED crowding is defined as a situation where demand for emergency services exceeds the ability of an ED to provide care within an appropriate time frame [1]. Globally, several individual healthcare systems and the International Federation of Emergency Medicine have identified ED crowding as a public health concern and health equity issue [1–3].

A conceptual framework has been developed to classify and measure crowding within emergency departments. This framework includes three “buckets”: input, throughput, and output [4]. Input is defined as any factor that may increase the number of visitors to emergency departments, which can include a lack of access to primary care, an increase in the number of acutely presenting patients, and inefficient triage procedures [4, 5]. Throughput is defined as the flow of patients through the ED, which includes triage, time to diagnostic testing, and treatment [4]. Discharge of patients and movement to inpatient units represents the output component and represents a commonly cited reason for crowding in emergency departments [4, 6–9]. Output reflects challenges within healthcare systems as whole. This is especially emphasized considering when boarding of admitted inpatients within emergency departments is decreased, crowding and wait times are significantly reduced [4, 9].

The challenges for both staff and patients related to crowding and emergency department boarding were highlighted particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, where ED crowding spiked due to access block and the transmissibility of the coronavirus [10]. Furthermore, access block causes a dose–response increase in the rate of mortality for patients boarded in emergency departments [7, 11].

Further harms associated with crowding and increased boarding in EDs include longer time to treatment, which may in turn impact disposition and chances of admission [12]. Crowding has also been shown to increase chances of return visits to emergency departments and increased healthcare utilization [13]. These outcomes are also not equal to every patient, the longstanding impacts of crowding have been shown to disproportionately impact disadvantaged populations to a greater degree [3].

The metrics of crowding have been measured and reported in several ways to optimize reporting of causes and harms of crowding. Metrics include patient flow in hospital beds, ED length of stay, or ED volume [5, 14]. These metrics were developed to assist in studying and understanding research to influence clinical practice guidelines.

There is a growing body of literature investigating the causes, measures, and harms of crowding in emergency departments. Approximately 200 total studies have been published yearly on emergency crowding in the last five years. Of these, approximately 20 are systematic reviews. The selected systematic reviews inform further research on interventions which may then be used to provide solutions to the current crisis of crowding in emergency departments. However, the global literature has not yet been summarized in an overview of reviews format, which aims to summarize the current state of the literature on these issues. While solutions for the crowding concerns may be local, there is a need for evidence-based decision making, thus data synthesis is useful in this field.

This overview of reviews seeks to synthesize the field of ED crowding with a focus on the causes, harms, and measures of overcrowding in emergency departments. This review will apply a global perspective and will cover facets of emergency department crowding from the perspective of input, throughput, and output. A second overview of reviews, which will analyze data from 2010 onwards, will focus on interventions and solutions and be presented in a subsequent paper.

Methods

We compiled evidence from self-defined systematic reviews that assessed the factors that cause ED crowding, appraised the measures of ED crowding, and analyzed the outcomes and harms related to crowding. Methodology was supported by the current PRIOR statement [15] for overview of reviews.

Eligibility

Articles were considered to be within scope of the study if they were: self-defined systematic reviews; if the reviews included an analysis of input, throughput, or output in the emergency department; had quantitative data available on the metrics of overcrowding; included data on the harms of overcrowding; analyzed the causes of overcrowding; or if the reviews were emergency department reviews. Studies were excluded based on being the wrong study type; if they investigated the interventions of crowding in the emergency department; if the studies were published earlier than 2010; if the reviews investigated specific conditions related to overcrowding; or were related to inpatient units; or the reviews were specific to one country.

Search

A health sciences librarian with experience in systematic reviews (HG) searched MEDLINE and Embase on the Ovid platform, from inception to October 5, 2022, for subject headings and keywords related to the concepts of emergency department and overcrowding. A search filter for systematic reviews, originally developed by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health [16] was slightly modified to include scoping reviews and applied to the base search. Complete search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

During the extraction process, four reviewers sorted the reviews by population and intervention comparisons and extracted the primary studies that were used in the systematic review. The authors, populations, and outcomes were assessed by the reviewers. In the case of overlap, authors were to choose the newest article and the one of highest quality. However, given the broad search criteria and the global nature of this review, none of the reviews were excluded and moved forward to analysis. Reviewers independently extracted data from each systematic review, using a data table which was piloted by all reviewers. The primary author then confirmed the extraction data, and conflicts were resolved vis consensus with the whole team.

Data were extracted and tabulated for the following details: review title and author, the year of publication, the journal of publication, the databases which were searched for the study, the period surveyed by the study, the number of primary studies included, the types of primary studies which were included, the comparison groups in the study (if relevant), and the key findings from the authors. Furthermore, we extracted project specific metrics which included: the problems contributing to ED crowding, the metrics of crowding, and the harms of crowding.

Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias of the included systematic reviews using the systematic review specific JBI checklist tool [17]. The JBI tool evaluates possible biases in the reviews as well as evaluating the process used to establish the reviews. The JBI scores for each paper are included in Table 1. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of each included article, with disagreements settled by a third reviewer. Scores ranged from low quality to high quality, with most of the studies being of moderate quality. These ratings can be accounted for due to the study design associated with systematic review. However, when summarizing the results into the narrative synthesis, the results of moderate to high quality articles were considered more strongly. Risk of bias from the primary studies was collected using the JBI tool in each of the systematic reviews.

Table 1.

Description of Included Systematic Reviews

| Citation | Period of study | No. of studies | Type of study | Population | Study setting | Crowding indicator | Contributors to ED crowding | Key findings | Crowding harms | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [20] | Jan1980–Jan 2012 | 32 | Cross-sectional, cohort, case control, quality improvement, quasi-experimental and RCT | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to ED | USA, Australia Canada, Ireland, France, and Taiwan | Throughput | N/A |

No. of patients in waiting room, ED occupancy, and no. of admitted patients in the ED were metrics most frequently linked to ED quality of care (QoC) - 15 crowding measured studied had quantifiable links to QoC No publications had data on the relationship between crowding measures and efficiency or equitable care |

N/A | Moderate |

| [24] | Jan 2007–Aug 2018 | 106 | Cohort, qualitative, and systematic reviews | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | Not specified | Input, Throughput and output |

Critical illness, age extremes, male gender, - ED throughput causes (i.e. staff shortages, bed shortages) ED input causes (i.e. increase in patient numbers) ED output causes |

ED overcrowding is a multi-facet issue, which affects patient-related factors and emergency service delivery Crowding of the EDs adversely affected individual patients, healthcare delivery systems, and communities High importance of an integrated response to emergency related overcrowding and its consequences |

Harms to patients (decreased satisfaction, increased readmission, increased morbidity/mortality) Harms to healthcare system (i.e. decreased compliance increased staff workload, increased ED LOS) |

Moderate |

| [11] | Inception—Nov 2019 | 7 | Retrospective cohort, prospective cohort, and case control | Adult patients presenting to the ED | USA, Canada, Italy | Output | N/A |

ED boarding is associated with an increase in adverse events (AEs) and reduction in QoC - ED AEs influence the occurrence of unfavorable patient outcomes even after admittance to hospital |

Harms to patients: decreased QoC, missed ED treatment, missed home medications, delayed orders, delayed drug administration, higher mortality in boarded patients, increased risk of ICU admission, increased AE’s | Low |

| [19] | Jan 1966—Sept 2009 | 46 | RCT, cohort, and observational | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | Not specified | Input, throughput and output | N/A |

Most common input measures: total no. of patients in the waiting room, waiting room time, total number of arrivals Most common throughput measures: ED census, ED occupancy rate, and ED LOS Most common output measures: the number of ED admissions; the number of boarders, boarding time, and inpatient occupancy levels Crowding measurement can be separated into patient flow and nonflow measures, with nonflow being easier to observe but harder to generalize across ED’s |

N/A | Low |

| [27] | Jan 2007–Jan 2019 | 58 | Cross-sectional, cohort, survey, prospective pilot and review, cohort, regression, longitudinal, ecological, correlation, and quasi-experimental | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | Not specified | Input, throughput and output | N/A |

ED crowding affects individual patients, healthcare systems and communities at large Negative influences of crowding on healthcare service delivery result in delayed service delivery, poor quality care, and inefficiency; all negatively affecting patient outcomes |

Harms to patients: delayed assessment/treatment, increased walkouts, high patient readmission rate, prolonged hospitalization, high cost of treatment, low satisfaction, medication errors/adverse events, morbidity, mortality Harms to healthcare delivery: high workload, delayed service provision, discharging patients, with high risk features, diverting patients, high patient readmission rate, overutilization of imaging, poor infection prevention, low standards of care compliance, comprised QoC, high bed occupancy rate |

Moderate |

| [28] | Jan 2002—July 2012 | 11 | Case-crossover, prospective observational, retrospective cohort, correlational study, retrospective observational, prospective cross-sectional, and retrospective cohort | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | USA, Korea, Canada, and Australia | N/A | N/A |

ED crowding is a major patient safety concern associated with poor patient outcomes ED crowding is associated with higher rates of inpatient mortality among those admitted to the hospital from the ED and discharged from the ED to home ED crowding is associated with higher rates of individuals leaving the ED without being seen |

Harms to patients: increased LWBS Increased patient mortality Adverse cardiovascular outcomes Less likely to recommend the ED to others |

Moderate |

| [21] | Inception–Feb 2020 | 4 | Prospective observational, cross-sectional, and mixed-method | Pediatric patients presenting to the ED | USA and France | Input, throughput and output | N/A |

All models show promise, but their performance when used at other pediatric EDs and when compared to each other is not yet established Biggest challenge to this research is the lack of a “gold standard” comparator for measuring crowding Tools to measure pediatric ED crowding are not as advanced adult ED measures |

N/A | Moderate |

| [14] | Jan 1990–Dec 2020 | 90 | Observational, retrospective cohorts, survey, prospective cohort, prospective observational, retrospective case control, cross-sectional, retrospective cross-sectional, retrospective observational, and retrospective review of prospective cohort | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | USA, Canada, South Korea, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Netherland, Sweden, Colombia, UK, Taiwan, Belgium, Australia Italy, Spain, Iran, Ireland, and China | Input, throughput and output | N/A |

ED occupancy, ED LOS, and ED volume are homogenous in their definition, well studied, easy to understand, measure, and communicate - The electronic medical records have eased the obtention of the EDWIN and NEDOCS scores - NEDOCS is the most studied measure on the perception of care |

Harms to patients: increased mortality, decreased QoC, decreased perception of care | Low |

| [22] | Inception—Oct 2017 | 184 | Observational retrospective and observational prospective | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | USA, Canada, Australia, Europe, Asia, and UK | Throughput | N/A |

Worse quality of care was associated with total ED LOS and total ED occupancy - ED LOS was associated with worse quality of care across all six IOM domains: patient safety, effectiveness, patient-centred, timeliness, efficiency, and equity - ED occupancy was associated with all IOM domains, except equity - ED LOS and ED occupancy are different ways of measuring the same concept |

Harms to patients: worse QoC, poor care experience | Moderate |

| [25] | January 1995—January 2010 | 56 | Cohort, cross-sectional, audit reports of analyzed administrative databases, medical records, surveys, and interviews | Adult patients presenting to the ED | USA, Australia New Zealand, UK, Switzerland, and Canada | Input |

Aging of population Loneliness, vulnerability, lack of family support Increased presentation of complex mental health patients Limited access to a primary care physician Community awareness to seek early medical attention - Inappropriate or unnecessary ED attendances - Increased emergency ambulance utilization |

ED presentations are complex due to demographic changes, organizational changes, access to specialist, heightened health awareness and rising community expectations Aging population has an increased risk of more frequent acute illnesses and complications from age-related chronic diseases As the number of aging individuals continues to rise there will be an increase in demand for emergency care |

N/A | Low |

| [26] | Jan 2006—Dec 2018 | 20 | Cross-sectional, qualitative narrative accounts, descriptive survey, phenomenological approach using semi structured interviews, interpretive phenomenology unstructured interviews, descriptive correlational questionnaire, and qualitative exploratory with semi structured focus groups | Nurses working in the ED | USA, Iran, Canada, Saudi Arabia, AustraliaBelgium, Ireland, China, Spain, and Netherlands | Throughput | Decreased staffing (nurse retention rates impacted by: violence/aggression toward nurses, aggravated by boarding and long ED waits, negative work environment and overcrowded EDs) |

Organisational issues such as risk of violence and aggression, inadequate staffing levels, excessive workloads, and suboptimal work environments create significant adversity for ED nurses Adversity leads to poorer work quality which aggravates crowding and contributes to declines in ED nurse staffing, which may also lead to ED overcrowding |

Harms to patients: decreased Harms to healthcare system: interference with health and safety and infection control, nurses frustrated as unable to provide quality nursing care, staffing insufficiencies |

Moderate |

| [23] | Jan 2010—Dec 2019 | 28 | Retrospective observational, prospective observational, modeling, quasi experimental, and pragmatic cluster RCT | Adult and pediatric patients presenting to the ED | USA, Australia Canada, China, France, Italy, Portugal, Sweden, Netherlands, Germany and UK | Input, throughput and output | N/A |

ED LOS, door to provider, and LWBS rate were the most common outcomes for measuring the EDs efficiency - The length of time a patient waits to be treated is routinely used to measure ED performance; however, triage waiting times need to take into account the mix of patients and the mix of hospitals There is heterogeneity in definition for door-to-doctor time |

Harms to patients: increased mortality, decreased QoC and patient safety, reduced efficiency, increase in waiting times, decreased protection of confidentiality, decreased patient satisfaction, increase in premature discharge Harms to healthcare system: reduced motivation and gratification of staff, increase in the incidence of the burnout phenomenon, increase in episodes of violence by users |

Low |

| [8] | Jan 2000—Jun 2018 | 102 | Retrospective cohort, RCT, prospective observational, mixed-methods, retrospective case control, exploratory field study, retrospective data analysis, statistical modeling, and prospective interventional | Adult patients presenting to the ED | Singapore, UK, USA, Australia, Finland, Korea, Canada, New Zealand, Holland, Taiwan, Belgium, Sweden, and China | Input, throughput and output |

Input: more complex care needs, elderly patients, high volume of low acuity presentation, limited access to primary care in community Throughput: ED nursing staff shortages, presence of junior medical staff, delays in test results Output: access block, ICU and cardiac telemetry census |

Mismatch exists between causes and solutions to ED crowding—causes relate to the number/type of people attending ED and timely discharge, while solutions focused on efficient patient flow within the ED Solutions aimed at whole system initiatives to meet timed patient disposition targets, as well as extended hours of primary care, demonstrated promising outcomes |

N/A | High |

Data synthesis

We synthesized the data into a narrative review, which is supported by the tables of statistical outcomes reported in the original systematic reviews. Given the heterogeneity across studies in the various outcomes, no additional statistical analyses were conducted. We reported the results of the systematic search in a narrative fashion governed by the PRIOR statement and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement of reviews [15, 18].

Results

Results of the search process

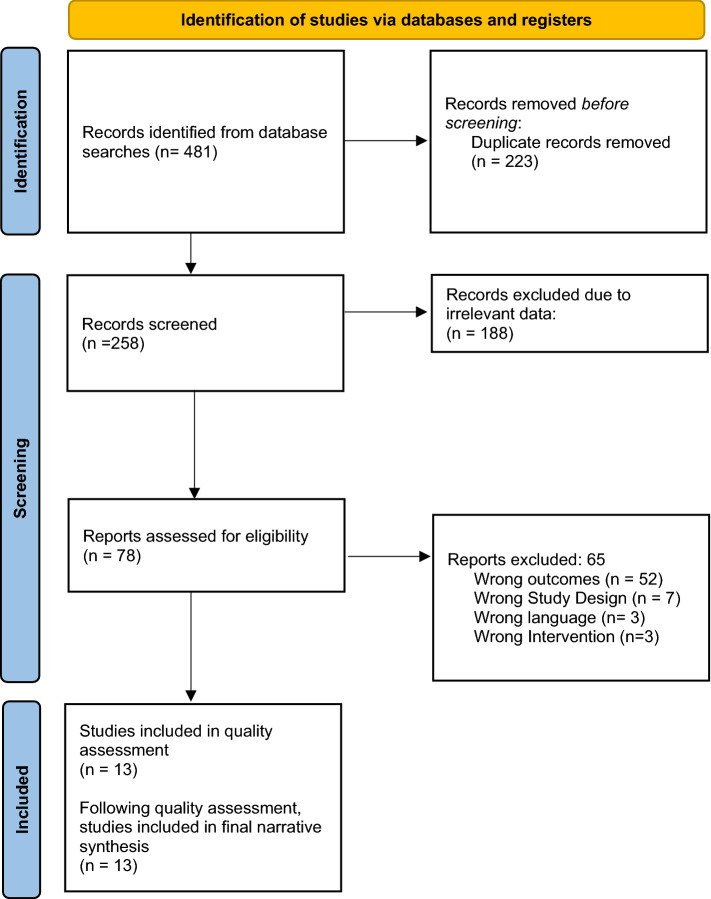

Two hundred and fifty-eight articles were retrieved from the seven identified databases. These articles were screened at the title and abstract stage, then 78 were screened in the full-text review. Thirteen full-text articles were included in the final review. These systematic reviews contained one hundred and eighty-seven individual primary studies, of which the majority consisted of observational studies, followed closely by randomized control trials. The PRISMA and Meta-Analyses flowchart of the study selection is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Description of included systematic reviews

Thirteen systematic reviews, each targeting aspects related to the causes, harms, and measures of emergency department crowding, were retained for this project. Several studies covered more than one category. The studies were grouped according to these categories: (a) Four reviews evaluated the validity of measures used to study emergency department crowding; (b) Four studies investigated the causes of emergency department overcrowding; and (c) Nine studies evaluated the possible outcomes and harms of crowding in emergency departments. Table 1 presents the main findings of each systematic review, as well as the evaluation of their characteristics and release date. The specific metrics of crowding that were evaluated by the systematic reviews are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Metrics of crowding in emergency departments in relevant systematic reviews

| Citation | Crowding metric |

|---|---|

| m |

LOS Boarder occupancy Overcrowding Hazard Scale No. of admitted patients ED LOS Waiting room time Physician waiting time ED occupancy No. of patients in waiting room No. of patients waiting to see provider Ambulance diversion No. of patients arriving in 6 h Total ED volume EDWIN score |

| [19] |

Waiting time Waiting room filled > 6 h/day Time to physician No. of arrivals No. of patients in waiting room No of patients registered No. of ambulance patients No. of triage patients Percentage of open appointments in ambulatory clinic Ambulance diversion episodes Average EMS waiting time ED bed Percentage of time in ED No, of full rooms Total no. of patients in the ED ED occupancy rate No. of hallway patients No. of resuscitations No. of patients waiting for specialty consults disposition by consultant > 4 h No. of ED diagnostic orders No. of patients waiting test results No. of nurses working Patients treated by acuity per bed hours No. of patients per provider No. of patients admitted or discharged per physician Sum of patient care time per shift ED ancillary service turnaround time Time to consultation Time to room placement ED treatment time ED LOS No. of admissions of boarders Boarding time—Observation unit census No. of patients waiting discharge/ambulance pick-up ED admission transfer rate Hospital admission source Inpatient occupancy level Hospital supply/demand forecast ED inpatient bed capacity No. of inpatients ready for discharge No. of staffed acute care beds Inpatient processing times Inpatient laboratory/radiology/CT orders Time from request to bed assignment Time from bed ready to ward transfer Agency nursing expenditures Local home care service availability Alternate level of care bed availability Nearby EDs diverting ambulances ED Work Score CBS System complexity Overcrowding Hazard Scale |

| [28] |

Waiting room time Waiting room census ED occupancy |

| [21] |

PEDOCS SOTU-PED Model mapping the flow of patients through the pediatric ED Model of physician work- load based on patient arrivals, presenting complaints and conditions, and tests ordered |

| [14] |

ED occupancy ED LOS ED volume ED boarding time No. of boarders ED waiting room census NEDOCS EDWIN |

| [22] |

Timeliness of care Time to assessment Treatment time Boarding time ED LOS Boarding occupancy ED occupancy Waiting room occupancy Hospital occupancy Hospital LOS Staff experience DNW |

| [23] |

Door to provider, Door to order time Door to disposition Door to physician LWBS LBVC Waiting time ED LOS Ambulance ramping Delay to FMC |

| [8] |

ED LOS LWBS DNW Hours of ambulance diversion Hours of access block Boarding hours Timed patient disposition targets EDWIN score NEDOCS ED census |

The primary studies consisted predominantly of observational studies. The studies were assessed by authors for overlap of the primary research used in the systematic reviews and determined that the study goals between the systematic reviews and the papers used were sufficiently unique to utilize the results of each systematic review independently.

Review findings

Metrics used to assess ED crowding

Measures of crowding in the emergency department serve multiple purposes. They provide a means with which to base research findings, as well as a quantitative measure that can be used to evaluate crowding interventions. Several metrics were noted to be used repeatedly in the systematic reviews and were appraised by authors for their effectiveness as well as the frequency of use in quality assurance and intervention research. A summary of the metrics that were evaluated by the relevant systematic reviews are included in Table 2. These could be classified broadly based on two headings: patient flow measures and metrics of patient occupancy [19]. Patient flow measures rely predominantly on time, whereas nonflow measures evaluate the number of people and utilization of resources [19]. Measures can be further subdivided into their aspect of emergency care: input, throughput, and output [14, 19–21]. A commonly assessed metric, which falls under the nonflow input category, is the number of waiting room patients and waiting room wait times, including time to triage and time to a bed in the emergency department [14, 21]. These metrics were found to be reliable across multiple studies, and reinforced by physician feedback, as a good evaluation of crowding and boarding in the emergency department [20]. Furthermore, the number of patients in the waiting room was linked to quality of care provided in the ED [22, 23]. A summary of the commonly investigated and relevant patient flow and occupancy metrics are contained in Table 3. From these, it was noted that the most prevalent measures included flow and metrics of occupancy, number of patients in the waiting room and the department, and the number of boarders.

Table 3.

| ED LOS | ED Census |

|---|---|

| Boarding time | Waiting room patients |

| Time to diagnostic imaging | Number of boarders |

| Time to inpatient bed after being admitted | Percentage of beds occupied by boarders within the department |

| Time in waiting room | Number of patients in the waiting room |

| Time to disposition | Number of ED arrivals |

| Number of hallway patients | |

| Number of ambulance diversions |

Length of stay in the emergency department, a flow metric reflective of throughput care, was also commonly used and highly predictive of the degree of crowding in emergency departments [14, 21, 23]. This was accompanied by various measures of ED occupancy, including at individual time points and over an established period [14]. These time-based metrics are also used to understand the treatment load in the emergency department. To better understand patient experience and the efficiency of emergency departments, time to diagnostic testing from entry to the ED can be used [14]. These throughput measures have been associated with patient safety and employee satisfaction and performance [14, 23].

Boarding, a core output metric, is most frequently measured using comparisons between throughput measures and more specific metrics. One specific measure of emergency department output and access block is the number of admitted patients awaiting inpatient beds, number of boarders in the department, percentage of beds occupied by boarders within the department, or time from admitting to movement out of the ED [20, 22]. This has been compared to the ED output measure of “number of patients ready for discharge” to evaluate conditions in the emergency department at a given time [14, 20, 21, 23]. Finally, the culmination of these factors, or the individual factors themselves can be correlated with ED mortality rates, which are commonly used to measure quality of care in the ED [23].

The combination of the input, throughput, and output measures can be used to generate objective scores which have consistently been found to be a better predictive of crowding in the emergency department [14, 19]. The noted measures have been mentioned across several primary studies, however, more research should be performed regarding the generalizability of measures and their performance across multiple emergency department settings [19, 21]. Two composite mathematical indices assessing crowding severity include the National Emergency Department Overcrowding (NEDOC) score and the Emergency Department Work Index (EDWIN) score [8, 14, 19]. Both metrics have demonstrated a strong association with clinician opinions of crowding, patients leaving without being seen, and ambulance diversion [19]. Moreover, both have proven studied impacts based on quantitative capacity and usage metrics and correlate with perception of care and objective crowding [24]. Nonetheless, in their current state these measures are effective tools to investigate crowding in global EDs and to investigate causes and possible interventions.

Causes of overcrowding

The causes of overcrowding, like measures of overcrowding, can be grouped to better understand the intricacies of each issue and to stratify possible solutions. Causes of crowding are broken down broadly into patient, service delivery, and healthcare system-related factors, which can be grouped further into how they impact input, throughput, and output service in emergency departments [25, 26].

Patient presentations can impact resource utilization, therein impacting time spent and possible crowding in global emergency departments [8]. Factors that may increase time spent in the ED include being critically ill, extremes of age, male gender, and social determinants of health [25]. Thus, the ageing of the population, particularly in North America, and increasing patient reported loneliness have been cited as factors that contribute to increased patient presentations and longer length of stay in the ED [25, 26]. The speed of service delivery to these patients is impacted by ED staff-related factors, which may further exacerbate crowding issues [27].

Emergency service delivery via healthcare staff and flow in the emergency department impacts crowding through input, throughput, and output metrics [25]. Service delivery factors include a delay to discharge or imaging and lab investigations, increased time to inpatient consultation, staff fatigue, and crowding itself, which causes delays to diagnostic tools and final diagnoses [8, 25–27]. Inadequate staffing of nurses, high rates of provider burnout, excessive workloads, and high staff turnover is strongly associated with throughput causes and may further aggravate crowding issues [27]. While these are staff-related factors, they can be exacerbated by system-related factors, wherein healthcare system environments can significantly worsen conditions for staff [8].

Crowding in EDs globally presents a system-wide healthcare related issue, and is worsened by lack of access to both primary care and tertiary care [25]. Globally, crowding has also been linked to a lack of access to non-urgent primary care centers, leading to increased low acuity presentations in emergency departments [8, 25, 26, 28]. Departments have also noted an increase in mental health and addictions presentation due to limited access to resources and primary care physicians [26]. Furthermore, boarding of admitted patients in the ED, the most commonly cited cause of crowding, is shown to be caused by a shortage of inpatient beds, which is a result of challenges in hospital wards manifesting as high occupancy levels [25]. It is important to acknowledge that crowding is a global healthcare challenge, but should be informed by local considerations in order to tailor interventions to identified causes [8].

Health and system impacts

The importance of investigating ED crowding is emphasized when understanding the impacts to patients, healthcare staff, and the healthcare system at large. [8, 11, 14, 22–25, 27, 28]. These outcomes are the basis of many measures that are used for crowding research in the ED and highlight the importance of this research. Patient harms of crowding, at its worst, include an increased risk for morbidity, adverse events, and mortality [6, 25, 28]. Lesser effects of crowding include delayed time to assessment, decreased quality of care, or medication errors which may cumulate in low patient satisfaction [11]. Crowding can also cause increased walkouts prior to receiving care, which may contribute to an increased chance of readmission and prolonged time in the hospital [14, 24, 25]. These patient factors are further exacerbated by the impacts that crowding has on the healthcare system.

Crowding’s influence on the system impacts quality of care and the health of providers and patients. Crowding results in an increased workload, which decreases performance and efficiency, and increases the amount of time that patients spend in the ED [8, 14, 28]. Furthermore, as was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic, a high rate of bed occupancy can result in poor infection prevention and the spread of respiratory infections [28]. All these factors, including poor compliance to quality of care and worse understanding of patient conditions can increase the cost of care and treatment in the ED [11, 13, 28].

Crowding is a major patient safety concern and has a large impact on the healthcare system and healthcare providers’ wellbeing. Understanding the magnitude of these effects should motivate the development of interventions to better control ED crowding in emergency departments globally.

Discussion

Emergency department crowding presents a global healthcare concern, with many inciting factors and consequential outcomes. The results of this overview of reviews group the main problems of overcrowding into the measures, causes, and consequences of overcrowding. Current literature, while heterogeneous, presents common themes with regards to the measurements, causes, and outcomes of crowding in global emergency departments. The measures that are used in crowding literature can be stratified based on their aspect of emergency care: input, throughput, and output. These were further divided into flow and non-flow metrics, wherein one review states that flow metrics are growing in use and popularity [20]. This is in alignment with recent works, which suggests that current literature is difficult to apply clinically due to heterogeny between measurements and a lack of a standard definition in many metrics, even when in the same geographical region [29, 30]. Additionally, it was in accordance with current literature that suggests that time-based targets may be most effective in evaluating the impacts of crowding and measuring interventions, which may warrant further research on these flow metrics [31, 32]

The major causes of ED crowding were broken down into patient-based, staff-based, and system-based factors. The most prevalent issue appears to be system based, resulting in access block, and exacerbating patient-related and staff-related factors. These results are consistent with current literature, which suggests that patient-based factors may put a strain on hospital resources and can be alleviated by systems-based solutions [33]. This is also consistent with research which identifies staffing shortages as both a cause and an outcome of crowding in EDs, though lack of standardization of staffing requirements limits research into its role as a cause [6, 8, 27]. Current literature, in line with the results reported in this literature, reports that ED crowding can be predicted by measuring boarding rates in the emergency department [34, 35]. Thus, it is important to target healthcare-level solutions to reduce the negative impacts of emergency department crowding [5].

The importance of managing crowding on an international scale cannot be understated as there are several various negative outcomes that have emerged due to crowding. These outcomes predominantly impact patients in terms of treatment quality and resulting management shortcomings. However, crowding has impacts on staff burnout and satisfaction, and has a proven financial impact on the healthcare system. The most commonly cited factor, and the most important in terms of patient care, is that ED crowding increases the chances of adverse events and mortality for patients [7]. In some cases, this association is profound; one study showed that for every 5 h spent in the ED, chance of mortality increased by over 50% [36]. Chances of poor outcomes are increased, because crowding is associated with poorer service delivery, patients leaving without being seen, and staff burnout [3, 24, 33, 37].

Future investigations should focus on the interventions which have found to be most effective with regards to the heterogeneous causes of crowding [14]. A current difficulty with current interventions is that they do not appear to be matching the issues that have been presented in the crowding literature [14, 38]. Thus, it is important to consider the specific community and national circumstances that are facing departments when proposing solutions. Furthermore, these results can be used to help inform the international conversation on the global harms, causes, and measures of crowding in emergency departments. This is the first overview of reviews to comprehensively synthesize the global literature on crowding in this context.

Limitations

A wide range of primary studies were utilized to produce the systematic reviews that were analyzed for this research. While this reflects the differences in global literature effectively, it results in differences in measurements and criteria within studies, making it difficult to standardize the results. To minimize this, we synthesized the results into a narrative review to descriptively summarize the outcomes of interest.

Another important factor that was considered is that the primary studies used to make the reviews were predominantly conducted in developed countries. Thus, the presented results may not reflect the current causes and outcomes of crowding in developing countries, which structure healthcare in a different way. The presented issues, therefore, may not manifest in the same way and may not be effectively studied using the same measurements in developed countries.

Conclusion

This overview outlined the results of 13 systematic reviews, which analyzed the current state of the literature in global emergency department overcrowding. The current state of ED crowding research employs a varied set of measurements that analyze all aspects of emergency care, including input, throughput, and output. While these accurately reflect crowding measures, there is a need to develop a standard validated set of measures that may be used to better understand crowding across jurisdictions, and thus on a global scale. Similarly, there are several factors which cause and contribute to crowding in global emergency departments. The foremost of these, reflected in every systematic review that analyzed causes, is inpatient boarding which causes access blocks and diverts bed usage from new incoming ED patients to those awaiting inpatient beds. Worldwide, ED crowding is having a negative impact on the mission of emergency care through worsening patient outcomes, ED staff and infrastructure, and healthcare spending. While the causes and solutions to ED crowding will be unique and require tailoring to local circumstances, the 13 systematic reviews highlighted here serve as a foundation for concerted evidence-informed efforts.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Affleck A, et al. Emergency department overcrowding and access block. Can J Emerg Med. 2013;15(6):359–370. doi: 10.1017/S1481803500002451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javidan AP, et al. The international federation for emergency medicine report on emergency department crowding and access block: a brief summary. Emerg Med J. 2021;38(3):245–246. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-210716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein SL, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asplin BR, et al. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(2):173–180. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansah JP, et al. Modeling emergency department crowding: restoring the balance between demand for and supply of emergency medicine. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0244097–e0244097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKenna P, et al. Emergency department and hospital crowding: causes, consequences, and cures. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2019;6(3):189–195. doi: 10.15441/ceem.18.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones S, et al. Association between delays to patient admission from the emergency department and all-cause 30-day mortality. Emerg Med J. 2022;39(3):168. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2021-211572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morley C, et al. Emergency department crowding: a systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0203316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JH, et al. Effect of a boarding restriction protocol on emergency department crowding. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63(5):470–479. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2022.63.5.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savioli G, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on crowding: a call to action for effective solutions to "access block". West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(4):860–870. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.2.49611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.do Nascimento Rocha, H.M., A.G.M. da Costa Farre, and V.J. de Santana Filho, Adverse events in emergency department boarding: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021;53(4):458–467. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoot NR, et al. Does crowding influence emergency department treatment time and disposition? J Am College Emerg Physic Open. 2020;2(1):e12324–e12324. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doan Q, et al. The impact of pediatric emergency department crowding on patient and health care system outcomes: a multicentre cohort study. CMAJ. 2019;191(23):E627–E635. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.181426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badr S, et al. Measures of Emergency Department Crowding, a Systematic Review. How to Make Sense of a Long List. Open Access Emerg Med. 2022;14:5–14. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S338079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gates M, et al. Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: development of the PRIOR statement. BMJ. 2022;378:e070849. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubbard W, et al. Development and validation of paired MEDLINE and Embase search filters for cost-utility studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):310. doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01796-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters MD. Not just a phase: JBI systematic review protocols. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(2):1–2. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang U, et al. Measures of crowding in the emergency department: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(5):527–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stang AS, et al. Crowding measures associated with the quality of emergency department care: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):643–656. doi: 10.1111/acem.12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abudan A, Merchant RC. Multi-dimensional measurements of crowding for pediatric emergency departments: a systematic review. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333794x21999153. doi: 10.1177/2333794X21999153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones PG, Mountain D, Forero R. Emergency department crowding measures associations with quality of care: a systematic review. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33(4):592–600. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Laura D, et al. Efficiency measures of emergency departments: an Italian systematic literature review. BMJ Open Qual. 2021;10(3):e001058. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2020-001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter EJ, Pouch SM, Larson EL. The relationship between emergency department crowding and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2014;46(2):106–115. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasouli HR, Aliakbar Esfahani A, Abbasi Farajzadeh M. Challenges, consequences, and lessons for way–outs to emergencies at hospitals: a systematic review study. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12873-019-0275-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowthian JA, et al. Systematic review of trends in emergency department attendances: an Australian perspective. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(5):373–377. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDermid F, Judy M, Peters K. Factors contributing to high turnover rates of emergency nurses: a review of the literature. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(4):390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasouli HR, et al. Outcomes of crowding in emergency departments; a systematic review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019;7(1):e52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris ZS, et al. Emergency department crowding: towards an agenda for evidence-based intervention. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(6):460–466. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.107078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe BH, McRae A, Rosychuk RJ. Temporal trends in emergency department volumes and crowding metrics in a western Canadian province: a population-based, administrative data study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):356. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson J, et al. Long emergency department length of stay: a concept analysis. Int Emerg Nurs. 2020;53:100930. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McRae AD, et al. A comparative evaluation of the strengths of association between different emergency department crowding metrics and repeat visits within 72 hours. CJEM. 2022;24(1):27–34. doi: 10.1007/s43678-021-00234-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eriksson CO, et al. The Association between hospital capacity strain and inpatient outcomes in highly developed countries: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(6):686–696. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3936-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith AJ, et al. Multisite evaluation of prediction models for emergency department crowding before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022 doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocac214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kenny JF, Chang BC, Hemmert KC. Factors affecting emergency department crowding. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2020;38(3):573–587. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plunkett PK, et al. Increasing wait times predict increasing mortality for emergency medical admissions. Eur J Emerg Med. 2011;18(4):192–196. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328344917e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorski JK, et al. Crowding is the strongest predictor of left without being seen risk in a pediatric emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;48:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valipoor S, et al. Data-driven design strategies to address crowding and boarding in an emergency department: a discrete-event simulation study. HERD. 2021;14(2):161–177. doi: 10.1177/1937586720969933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.