Abstract

To investigate the bacteria that are important to phosphorus (P) removal in activated sludge, microbial populations were analyzed during the operation of a laboratory-scale reactor with various P removal performances. The bacterial population structure, analyzed by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with oligonucleotides probes complementary to regions of the 16S and 23S rRNAs, was associated with the P removal performance of the reactor. At one stage of the reactor operation, chemical characterization revealed that extremely poor P removal was occurring. However, like in typical P-removing sludges, complete anaerobic uptake of the carbon substrate occurred. Bacteria inhibiting P removal overwhelmed the reactor, and according to FISH, bacteria of the β subclass of the class Proteobacteria other than β-1 or β-2 were dominant in the sludge (58% of the population). Changes made to the operation of the reactor led to the development of a biomass population with an extremely good P removal capacity. The biochemical transformations observed in this sludge were characteristic of typical P-removing activated sludge. The microbial population analysis of the P-removing sludge indicated that bacteria of the β-2 subclass of the class Proteobacteria and actinobacteria were dominant (55 and 35%, respectively), therefore implicating bacteria from these groups in high-performance P removal. The changes in operation that led to the improved performance of the reactor included allowing the pH to rise during the anaerobic period, which promoted anaerobic phosphate release and possibly caused selection against non-phosphate-removing bacteria.

To meet existing and future effluent license commitments, wastewater treatment plants worldwide are required to more efficiently remove nutrients such as phosphorus (P). The two main P removal approaches are chemical precipitation and biological accumulation of phosphate. Knowledge of the biological process known as enhanced biological phosphorus removal (EBPR) has advanced over the last 20 years. Full-scale activated-sludge plants now operate for efficient P removal without the use of chemical precipitation (7, 8, 19, 47). In the basic configuration of an EBPR activated-sludge plant, the influent wastewater flows into an anaerobic zone where it is mixed with the returned microbial biomass from the clarifier to form the so-called mixed liquor. This mixed liquor then flows into an aerobic zone, after which the biomass is separated from the treated wastewater in the clarifier. Polyphosphate-accumulating organisms (PAOs [49]) are selected for in these systems under suitable conditions, and in the aerobic zones, excessive phosphate accumulation occurs. Removal of a portion of the growing biomass (waste-activated sludge) results in the net removal of P from the wastewater.

Biological models have been developed to explain how the PAOs achieve phosphate removal and how they are selected for in the EBPR system (43, 45, 53). These models have been established primarily from the findings of investigations carried out on mixed-culture activated sludge. Therefore, knowledge of the biochemical reactions of the EBPR process is largely derived from indirect observations and theoretical considerations. Because the biochemical details are lacking, engineers use a “black box”-type approach for design and optimization of EBPR activated-sludge systems. Knowledge of the biochemical mechanisms would assist in the improvement of the performance and stability of the EBPR process, since the biological process is not optimized and has been observed to fail (23).

Microbiological details pertinent to EBPR are lacking since it has not yet been established which bacteria are important to the process. In the past, culturing techniques have been used to determine PAOs, but the inadequacies of these methods for the analysis of microbial communities in environmental samples have been experimentally shown (18, 29, 35, 50). One genus of bacterium frequently cultured and suspected to have a role in EBPR is Acinetobacter, in the γ subclass of the class Proteobacteria (21). However, the use of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probing (29, 51) and cloning of 16S ribosomal DNA (11) to describe activated-sludge bacterial communities has shown that actinobacteria (gram-positive bacteria with high mole percent G+C content) and β-proteobacteria are dominant in EBPR mixed communities.

While trying to associate organisms with EBPR by mixed-culture investigations, it is important to have detailed, long-term operating data of the EBPR process. In some studies, details of performance of P removal by the sludge are not given or are inadequate, making it difficult to assess the significance of the microbiological results to EBPR. Laboratory-scale EBPR systems with high mixed-liquor suspended-solids (MLSS) P content (6 to 17%) and detailed operating data have been reported (5, 32, 43, 45, 52). They should have a large proportion of PAOs in their bacterial communities, which should be analyzed by FISH and cloning to identify the PAOs.

There have been recent reports of bacteria inhibiting EBPR in laboratory-scale activated-sludge systems designed for P removal (15, 33, 42). The microbial transformations in these systems have been investigated, and a biochemical model describing the bacterial inhibition of EBPR has been proposed (42). Microorganisms in these systems in which deterioration of P removal is evident have been labelled glycogen-accumulating nonpolyphosphate organisms, or GAOs (37). As with PAOs, there is little known about the ecological details of GAOs and how they affect EBPR. For example, if GAOs compete with PAOs, their presence could partially explain why optimal performance is not always attained in full-scale EBPR systems. However, there is also the possibility that the PAO and the GAO are the same organism. In that case, variable P removal could result from an alteration in the phosphate-accumulating capabilities of that particular bacterium. If more were known about PAOs and GAOs, the development of strategies to improve the P removal performance of a system would be more focused.

The goal of this study was to assess the importance of particular bacterial populations to the EBPR process by performing detailed chemical analyses of the P removal performances of the sludges and by investigating the microbial ecology by FISH. In particular, sludges with high-performance P removal capabilities were studied. During the operation of the sequencing batch reactor (SBR) for EBPR, periods with differing P removal capacities were observed. On two occasions, the reactor sludge performance and characteristics were investigated in detail. One sludge exhibited extremely poor P removal (P content of 1.8%; predominance of GAOs), while the other displayed extremely good P removal (P content of 8.6%;predominance of PAOs). This gave us a unique opportunity to determine the identity of PAOs and GAOs in these systems by FISH. This analysis indicated that the presence of certain bacterial types was correlated with P removal performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Operation of the SBR.

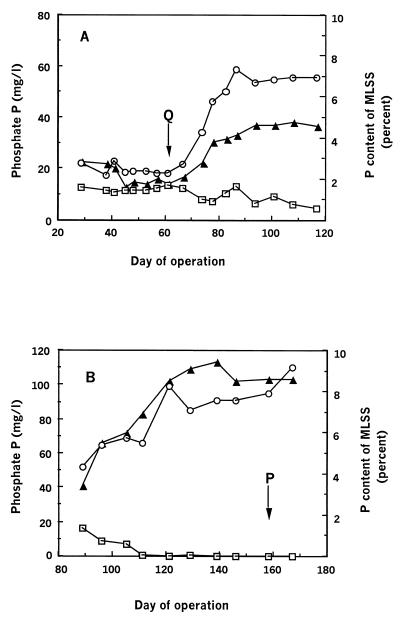

There were two stages of SBR operation during which the reactor was used for EBPR (Fig. 1). Stage A covered 117 days, and for a later stage, B, 78 days of operation are described. During the operation, changes were made to the SBR operating conditions to alter EBPR performance. At the end of stage A, the sludge was discarded and the reactor was restarted for the operation of stage B. Approximately weekly, so-called cycle studies were carried out on the reactor sludge to characterize its performance and samples were taken for investigations of the bacterial communities.

FIG. 1.

Performance of SBR during stage A (A) and stage B (B) of operation. Symbols: □, phosphate P concentrations in filtered effluent samples; ○, phosphate P concentrations in filtered samples from the end of anaerobic-stage mixed liquor; ▴, P content of the sludge, expressed as a percentage of the mass of the MLSS. Labelled arrows indicate the time points during operation when sludges Q and P occurred.

The SBR was operated in a Setric Genie laboratory fermentor with a working volume of 2 liters. This was operated in a sequencing batch mode in an air-conditioned laboratory maintained at 22 ± 2°C. The reactor was fitted with pH electrodes and, periodically, a portable dissolved-oxygen electrode. During stage A, the reactor operated with a 6-h cycle that consisted of 2.5-h anaerobic, 2.3-h aerobic, and 1.2-h settling/decanting periods. In stage B, a similar 6-h cycle was employed, consisting of 2-h anaerobic, 3.5-h aerobic, and 0.5-h settling/decanting periods. In both stages of operation, a hydraulic retention time of 12 h was maintained as 1 liter of medium was fed in the first 10 min of the anaerobic period and 1 liter of treated supernatant was withdrawn in the last 5 min of the settling stage. Mixed liquor was wasted during the aeration period so that the solids retention time was 8 days in stage A and 6.7 days during stage B.

When pH control was used, the pH was maintained at 7.0 ± 0.2 by addition of 0.2 M HCl and 0.25 M NaOH. Initially in stage A, the pH control operated in both the anaerobic and aerobic periods. After day 66 of stage A, and for the whole of stage B, the pH control operated in the aerobic period only.

Mixing throughout the anaerobic and aerobic periods was achieved by stirring at 400 rpm. Air was removed from the reactor in the anaerobic period by slow bubbling of N2 gas. Periodically, the mixed-liquor dissolved-oxygen levels were measured in the anaerobic stages, but none was detected. During the aerobic period, dissolved oxygen was maintained at above 50% saturation by bubbling air through the reactor at approximately 50 liters/min. All operations of the reactor were controlled by electronic timers, peristaltic pumps, and gas valve solenoids.

Media.

For both stages of operation, a base medium was used comprising (per liter) 90 mg of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 160 mg of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 42 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, and 0.3 ml of nutrient solution. The nutrient solution contained (per liter) 1.5 g of FeCl3 · 6H2O, 0.15 g of H3BO3, 0.03 g of CuSO4 · 5H2O, 0.18 g of KI, 0.12 g of MnCl2 · 4H2O, 0.06 g of Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 0.12 g of ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 0.15 g of CoCl2 · 6H2O, and 10 g of EDTA. Phosphate was added to the medium as KH2PO4 and K2HPO4 at a 1.2:1 weight ratio to obtain P concentrations of 15 and 24 mg/liter during stages A and B, respectively. In stage A, the carbon and nitrogen sources were added to the base medium as 850 mg of NaCH3CO2 · 3H2O/liter, 4 mg of Bacto Yeast Extract (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.)/liter, and 60 mg of NH4Cl/liter. During stage B, the following were added to the base medium: 700 mg of NaCH3CO2 · 3H2O/liter, 122 mg of Bacto Peptone (Difco Laboratories)/liter, 20 mg of Bacto Yeast Extract (Difco Laboratories)/liter, and 50 mg of NH4Cl/liter. The medium was made up with reverse-osmosis-deionized water, adjusted to pH 7.0, and autoclaved. To inhibit nitrification, allylthiourea was added intermittently to the reactor during stage A; however, in stage B it was included in the medium at 0.5 mg/liter.

Seeding of the SBR.

Prior to stage A, the reactor was seeded with activated sludge from another laboratory-scale SBR successfully operating for P removal. After stage A and prior to stage B, the reactor was reseeded with sludge from a full-scale activated-sludge plant successfully operating for EBPR.

Reactor analyses.

The performance of the reactor was superficially assessed by determination of the supernatant P and acetate levels at the end of the anaerobic and the aerobic periods, by the effluent P concentration, and by the percentage of P in the sludge. P and acetate levels were also determined for each batch of feed prepared. Weekly or biweekly during the operation of the reactor, cycle studies were done. These involved collection of samples from the reactor at 30-min intervals during one discrete cycle for determination of supernatant acetate and P levels and cellular carbohydrate and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) contents.

Chemical analyses.

Phosphate and chemical oxygen demand (COD) in filtered (Whatman cellulose nitrate membrane, 0.2 μm pore size) samples were determined by using Merck Spectroquant kits and an SQ118 spectrophotometer (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Total phosphorus of the mixed liquor was determined in duplicate 10-ml samples by the sulfuric acid-nitric acid digestion method (4); the phosphate was then quantified with the Merck Spectroquant kit. The mixed-liquor suspended solids (MLSS) were determined in duplicate 20-ml samples filtered onto predried Whatman GF/C filters and dried to a constant weight at 104°C.

Quantification of acetic acid was carried out by gas chromatography. Samples were filtered through Whatman cellulose nitrate (0.2-μm-pore-size) membranes and acidified to a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol) orthophosphoric acid. A Perkin-Elmer Autosystem gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a DB-FFAP column (internal diameter, 0.53 mm; film thickness, 1.0 μm; length, 15 m) and a flame ionization detector was used. The injector temperature was 220°C, and a sample volume of 1.0 μl was used. The carrier gas, high-purity helium, was used at a flow rate of 30 ml/min. The initial column temperature was 100°C, which was increased by 7°C/min to 140°C and then by 20°C/min to 220°C and held at that temperature for 5 min. The run time was 16 min, and the detector temperature was 250°C.

For the analysis of PHA, a modified version of the method of Braunegg et al. (12) was used. Duplicate 20-ml samples of mixed liquor were obtained and immediately centrifuged at 4°C; the frozen sludge pellet was then lyophilized. To the dried pellet, in a tube closed with a Teflon-lined screw cap, were added 2 ml of acidified (3% sulfuric acid) methanol and 2 ml of chloroform. This was digested for 20 h in an oven at 104°C. After the digest was cooled to room temperature, 1 ml of water was added and the tube contents were shaken for 10 min. The chloroform phase settled to the bottom of the tube, and this was drawn off for GC analysis. The digested product was detected on a Varian 3400 GC fitted with a 1.8-m Alltech 0.2% Carbowax 1500 on Graphpac-GC 80/100 mesh stainless steel column. The injection temperature was 180°C, the column temperature was 170°C, and the flame ionization detection temperature was 200°C. PHAs poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid and poly-β-hydroxyvaleric acid were quantified by comparison to a standard consisting of a copolymer of the above-described alkanoates (Fluka).

Total cellular carbohydrate in the mixed liquor was measured by digestion to glucose, which was detected by high-performance liquid chromatography. Duplicate 5-ml samples were acidified to a final concentration of 0.6 M hydrochloric acid. The samples were digested in a boiling-water bath for 1 h. After cooling and centrifugation of the samples, glucose in the supernatant was quantified in a Waters M-45 HPLC high-performance liquid chromatography unit fitted with a Bio-Rad HPX-87H column and a Perkin-Elmer 200 RI detector. Sulfuric acid (0.008 M) was the mobile phase, with a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min, and the volume of sample injected was 30 μl. The column temperature was set at 65°C, and the detector temperature was set at 35°C.

Staining for light microscopy.

Staining of sludge metachromatic granules was carried out with Loeffler methylene blue (38). Staining for lipophilic granules was carried out with the Sudan black stain (28). In this article, the lipophilic granules are referred to as PHA granules.

Sampling and cell fixation.

Immediately after mixed-liquor samples were taken from the mid-aerobic stage in the SBR, they were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 130 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.2]) and fixed in a 3% paraformaldehyde–PBS solution. The fixed samples were washed in PBS, resuspended in a PBS–96% ethanol solution (1:1, vol/vol), and stored at −20°C prior to hybridization (2). For in situ hybridization of gram-positive bacteria, the mixed-liquor samples were fixed by addition of ethanol to a final concentration of 50%; these samples were then stored as described above (41). Prior to hybridization, the fixed cells were immobilized on precleaned glass slides and dehydrated in 50, 80, and 96% ethanol solutions (3 min each) (34).

On one occasion it was necessary to disperse the sludge flocs by mild sonication to permit cell counting. The fixed cells were sonicated for 10 s in 2% Triton X-100 with a Branson Sonifier set at a 50% pulse and an output power of 1.5. Cells were washed and then resuspended in equal volumes of PBS and ethanol prior to being immobilized on glass slides as described above.

Oligonucleotide probes and in situ hybridization.

Oligonucleotide probes (Table 1) were synthesized with a C6-trifluoroacetyl amino linker at the 5′ end for use either in Germany (MWG Biotech, Ebersberg) or in Australia (Centre for Molecular and Cellular Biology, Brisbane, or Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). The probes were labelled with the N-hydroxysuccinimidester of the indocarbocyanine dye CY3 (Biological Detection Systems, Pittsburg, Pa.), tetramethylrhodamine-5-isothiocyanate (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), or 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FLUOS; Boehringer Mannheim) and purified as described by Amann et al. (3).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide probe sequences and target sites

| Probe | Sequence (5′-3′) | rRNA target sitea | Specificity | % Formamide | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | 16S, nt 338–355 | Bacteria | 20 | 2 |

| ALF1b | CGTTCG(C/T)TCTGAGCCAG | 16S, nt 19–35 | α-Proteobacteria | 20 | 34 |

| BET42a | GCCTTCCCACTTCGTTT | 23S, nt 1027–1043 | β-Proteobacteria | 35 | 34 |

| BONE23a | GAATTCCATCCCCCTCT | 16S, nt 663–679 | β-1-subgroup proteobacteria | 35 | 1 |

| BTWO23a | GAATTCCACCCCCCTCT | 16S, nt 663–679 | Competitor of BONE23a | 35 | 1 |

| GAM42a | GCCTTCCCACATCGTTT | 23S, nt 1027–1043 | γ-Proteobacteria | 35 | 34 |

| HGC69a | TATAGTTACCACCGCCGT | 23S, nt 1901–1918 | Actinobacteria | 25 | 41 |

Escherichia coli rRNA numbering (13). nt, nucleotides.

The in situ hybridization of the fixed samples on glass slides was carried out in a buffer containing 0.9 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 25 to 50 ng of oligonucleotide probe, and various amounts of formamide (Table 1). The slides, with the hybridization buffer, were incubated in an equilibrated humidity chamber at 46°C for 90 min. The hybridization solution was then rinsed off the samples with wash buffer, and the slides were immediately immersed in wash buffer and incubated for 15 min at 48°C. To achieve the same stringency during washing as during hybridization, the wash buffer contained 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5 mM EDTA, and between 0.9 M and 7 mM NaCl, according to the formula of Lathe (30), applied with a destabilization increment for the DNA-RNA hybrids of 0.5°C per percent formamide. Slides were then rinsed in distilled water, air dried, and mounted with Citifluor AF1 (Citifluor Ltd., Canterbury, United Kingdom) prior to viewing. To enhance single-mismatch discrimination during hybridization with probes GAM42a, BET42a, BONE23a, and BTWO23a, equal concentrations of the appropriate competitor probe were included in the hybridization buffer (34, 46).

Cells were detected by staining the samples with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; 0.33 μg/ml) at room temperature for 5 min (24) after in situ hybridization. Counting of cells was done with a Zeiss (Jena, Germany) Axioplan epifluorescence microscope fitted with a 50-W high-pressure bulb and filter sets Zeiss 01 (for DAPI) and Chroma HQ 41007 (Chroma Tech. Corp., Brattleboro, Vt.) (for CY3). For each of the probes used, more than 10,000 cells stained with DAPI were counted, except for probes BONE23a and BTWO23a, in which case at least 3,000 DAPI-stained cells were counted.

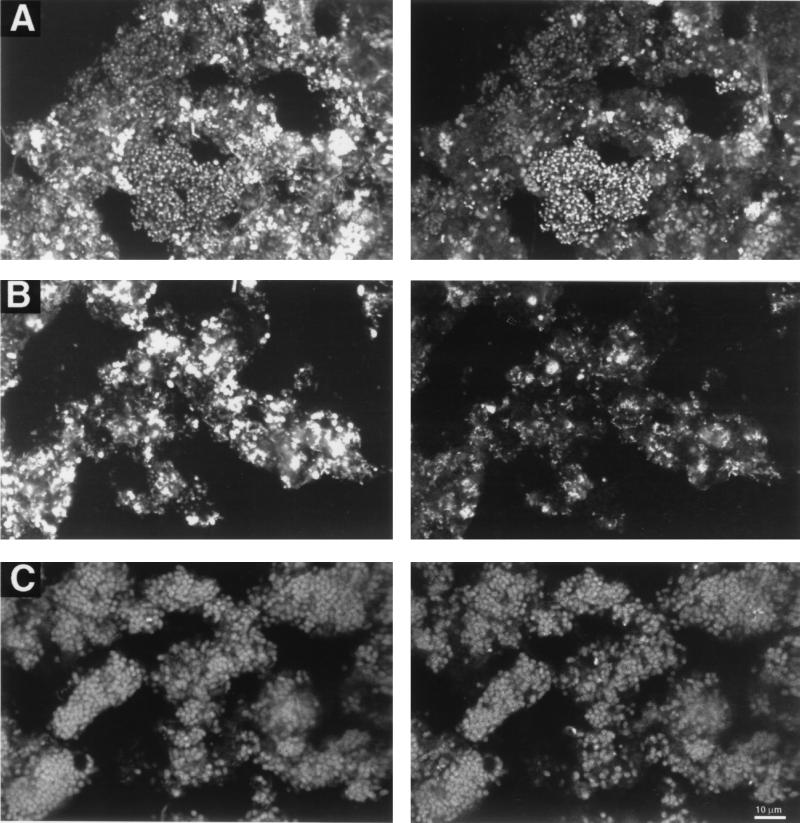

The images presented here (see Fig. 4) were obtained by using a Bio-Rad MRC 600 confocal laser scanning unit mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop microscope fitted with K1/K2 filter sets (Bio-Rad) (blue excitation was at 488 nm, with emissions collected at 522 nm [filter model DF32]; green excitation was at 568 nm, with emissions collected at 585 nm [filter model EFLP]). Images were collected by COMOS image analysis (Bio-Rad) and converted to TIFF files with Adobe Photoshop, and dye sublimation prints were produced with a Tektronik Phaser 440 printer.

FIG. 4.

FISH of the P sludge (A and B) and the Q sludge (C). Two images are presented for each view. On the left are cells binding fluorescein-labelled bacterial probe EUB338. On the right are the corresponding views of cells binding rhodamine-labelled probes BET42a (A and C) and HGC69a (B). Bar = 10 μm (applies to all panels).

RESULTS

Phosphate removal performance.

The EBPR performance of the SBR is described in two stages, A and B (Fig. 1), although the operating period extended beyond these stages. While the reactor was operated to achieve EBPR throughout these stages, changes were made to the initial operating conditions to improve the reactor performance. To monitor the P removal performance, the reactor was checked for typical characteristics of EBPR, such as low phosphate levels in the effluent, anaerobic phosphate release, high levels of cellular phosphate during aerobic periods, and anaerobic carbon substrate uptake (acetate uptake). Differences in phosphate removal performance were observed throughout these stages as detailed below.

(i) Stage A.

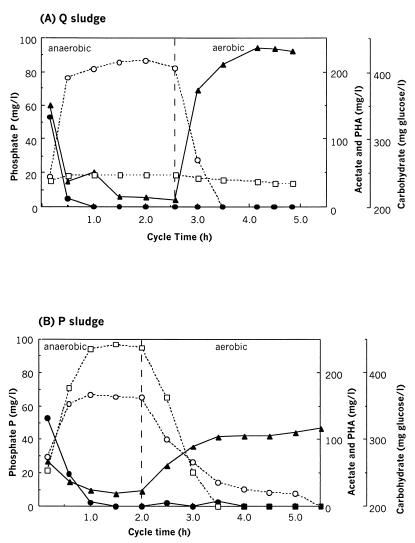

The P removal performance was less than optimal throughout stage A and extremely poor from days 29 through 67. The so-called Q sludge (Fig. 1A) demonstrated carbon transformations characteristic of EBPR (i.e., rapid uptake of acetate, accumulation of cellular PHA, and degradation of carbohydrate) but not P transformations, as demonstrated in a cycle study (Fig. 2A). Enhanced P removal did not occur, since the soluble phosphate P concentration in the influent averaged 15.1 mg/liter while that in the effluent averaged 12.0 mg/liter. There was very little anaerobic release of phosphate from the Q sludge, with release averaging just 6.8 mg of P/liter, and the P content was low, at less than 2% of the MLSS.

FIG. 2.

Profiles of soluble extracellular phosphate P concentrations (□), extracellular acetate (●), cellular polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) (○), and cellular carbohydrate (▴) during the anaerobic and aerobic reactor cycle stages at the time of production of the Q sludge (A) and the P sludge (B).

During the poor P removal in stage A, it was noticed that if the pH control was switched off in the anaerobic period, the pH of the reactor contents increased to about 8.5. This anaerobic pH increase coincided with the uptake of acetate, and an immediate small increase in the anaerobic phosphate release occurred. Because the pH increase seemed to stimulate EBPR behavior, the pH control was left off in the anaerobic periods throughout most of the remainder of stage A, from days 66 through 117. Indeed, from day 66 on, improved P removal performance was observed (Fig. 1A). By the end of stage A, the anaerobic phosphate P release had increased substantially, to 45.4 mg/liter (compared to 6.8 mg/liter for the Q sludge), the P content of the MLSS increased to around 4.6%, and the effluent phosphate P concentration eventually decreased to approximately 5 mg/liter. Although an improvement in P removal was slowly obtained throughout this period, this was still not optimal compared to the performance of other, similar laboratory-scale reactors, which achieved less than 1 mg of phosphate P/liter in the effluent (5, 44). This stage of reactor operation was terminated at day 117, and the sludge was discarded.

(ii) Stage B.

During 85 days of moderate P removal in stage B (results not shown), changes to the reactor operation included shortening of the anaerobic period to 2 h and the addition of peptone to the synthetic feed. As the COD in the feed had been increased to 500 mg/liter, the phosphate P concentration was increased to 24 mg/liter to maintain the low COD:P ratio in the feed. From days 89 to 167 of stage B (Fig. 1B), the carbon substrate was completely consumed in the anaerobic periods, and from day 111 on, excellent P removal occurred. On day 158, a cycle study (Fig. 2B) of the so-called P sludge (Fig. 1B) showed carbon compound transformations similar to those occurring in the Q sludge (Fig. 2A), except that the rates of carbohydrate and PHA utilization and synthesis in the P sludge were lower than those of the Q sludge (Fig. 2). The effluent phosphate P concentration was always lower than 1 mg/liter and most often below the detection limit (0.05 mg of P/liter). From day 121 on, the average level of anaerobic phosphate P release had risen to 82.7 mg/liter and the average P content of the MLSS was 8.8%.

Microscopic analysis of the Q and P sludges.

Microscopic examination of the Q sludge showed that it was dominated by one morphological cell type, a large (ca. 2-μm-diameter) gram-negative coccobacillus arranged in dense clusters of cells. These cells stained positive with Sudan black, with each cell containing a number of lipophilic granules, indicating the accumulation of a lipid material such as PHA. Cells from the aerobic stage of the reactor did not stain positive for polyphosphate.

Microscopic examination of the P sludge indicated that a diverse range of cells was present. Small numbers of tetrad-arranged cells fitting the description of the “G-bacterium” cell morphology were evident (10, 16). Polyphosphate-positive clusters of coccobacilli, approximately 1 μm in diameter, were observed in the flocs. This is typical of the PAO cell morphology and arrangement previously described (9, 14, 20, 21). A diverse range of cell types, including those fitting the PAO cell morphology, was found to stain positive for PHA inclusions.

Samples of the Q sludge, obtained on day 61 of stage A, and of the P sludge, obtained on day 158 of stage B, were fixed for analysis by FISH. Microscopic examination of the Q sludge indicated that the cells were bound in densely packed clusters in the bacterial flocs. To improve the appearance of the flocs for cell counting, the sludge was subjected to very mild sonication. The floc structure of the P sludge was not so dense and did not require sonication prior to FISH.

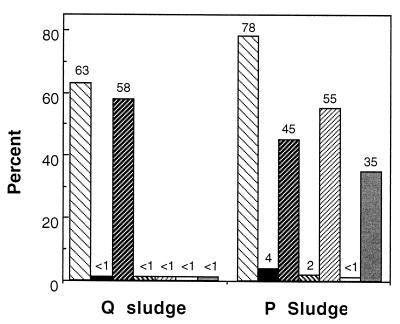

FISH probing (Table 1) of the Q and P sludge flocs detected individual cells of α-, β-, and γ-proteobacteria and of actinobacteria. Generally the activity of the cells in the Q and P sludges was weak, according to the probe signal, so CY3-labelled probes were used to increase the sensitivity of the hybridization for cell counting (22). Cell counts obtained for the Q and P sludges during hybridization events are presented in Fig. 3 and are given as percentages of the DAPI-stained cells hybridizing with the specific probes. Of the cells staining with DAPI in the Q sludge, 63% were detected with the general bacterial probe EUB338, and in the P sludge, 78% were detected with EUB338.

FIG. 3.

Bacterial-community analysis of the Q and P sludges as

determined by FISH cell counts. The values obtained with the probes

EUB338 (▧), ALF1b (▪), BET42a

(

), BONE23a (▧),

BTWO23a (▨), GAM42a (□), and HGC69a

( ) are

expressed as percentages of the number of cells detected with the DAPI

stain.

) are

expressed as percentages of the number of cells detected with the DAPI

stain.

FISH indicated that the Q sludge was dominated by bacteria that hybridized with the β-proteobacterial probe (BET42a) (Fig. 4C); they comprised 92% of the EUB338-positive cells (Fig. 3). However, very small numbers of cells (<1%) were detected with the β-proteobacterial subgroup probes BONE23a and BTWO23a. Cells binding the BET42a probe were morphologically uniform, large coccobacilli (diameter of 1 to 2 μm) resembling the cells with PHA inclusions.

The P sludge was dominated by bacteria that hybridized with the probes BET42a (β-proteobacterial probe; 45%) (Fig. 4A) and HGC69a (actinobacterial probe; 35%) (Fig. 4B), which virtually constituted all of the detectable cells (Fig. 3). A high count of cells detected with the probe BTWO23a (β-2-proteobacterial probe) was obtained (55%) (Fig. 3), while few were detected with the probe BONE23a (β-1-proteobacterial probe; 2%) (Fig. 3). Thus, the β-proteobacteria detected in the P sludge were different from those in the Q sludge. Cells hybridizing with probes BET42a and BTWO23a were mostly coccobacilli arranged in clusters (Fig. 4A). Cells hybridizing with the probe HGC69a (actinobacterial probe) were often the most brightly staining cells in the P sludge and were present mainly as small short rods (approximately 0.4 by 0.6 μm) either arranged as small aggregates or scattered throughout the bacterial flocs (Fig. 4B).

Very few γ-proteobacteria were detected in either the Q or P sludge (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Operation of SBRs and their evaluation by FISH.

In this study, mixed microbial cultures with extremes of P removal performances were obtained. Each culture operated stably, with the Q sludge demonstrating virtually no P removal for 38 days (4.8 sludge ages) and the P sludge exhibiting nearly complete P removal from the wastewater for 56 days (8.4 sludge ages) (Fig. 1). The detailed analyses of the transformations occurring throughout the cycles studied for the Q and P sludges were similar to those reported elsewhere for poor (42) and good (36, 43, 45) P-removing sludges, respectively. The molar ratios of the transformations determined for the Q and P sludges matched well the theoretical values suggested in the biological models (Table 2). Therefore, bacterial-community analyses of the Q and P sludges should indicate the presence of bacteria important in terms of the failure or success of EBPR.

TABLE 2.

Anaerobic transformations observed during SBR cycle studies compared with theoretical values

FISH with oligonucleotide probes specific for rRNA was used to analyze the bacterial populations of the two sludges. FISH of other sludges has been used successfully by other researchers (35, 46, 50). The microbial communities of the Q and P sludges were selectively enriched for specific properties. Due to this enrichment, their microbial diversity is likely to be less complex than that of sludges from full-scale processes, in which many different microbial functions occur and for which the influent wastewater is extremely complex. Thus, correlation of dominant microbial groups with specific mixed-culture attributes is more realistic in the enriched cultures.

Q sludge.

In the Q sludge, 92% of the cells detected by FISH were β-proteobacteria with a distinctly uniform cell morphology (Fig. 4C) and were different from the majority of cells detected in the P sludge with regard to cell morphology, FISH results, and PHA staining. Due to the extreme dominance of these β-proteobacteria in the Q sludge, it is likely that they play a major role in sludge metabolism. We described them as GAOs, and our attempts to isolate them by micromanipulation onto solid media were unsuccessful (results not shown). G bacteria, cocci in typical tetrad arrangements which have been identified as α-proteobacteria (10), have been associated with the inhibition of P removal (15). We observed no cells with the characteristic G-bacterium tetrad morphology hybridizing with the probe for α-proteobacteria, indicating that different bacteria are involved in poor P removal performance in EBPR reactors.

A laboratory-scale reactor sludge with chemical characteristics similar to those observed for the Q sludge was recently described by Liu et al. (31), although that sludge was generated under P-limiting conditions. It was examined microscopically and found to be dominated by three distinctive morphological cell types. One of the cell types was similar to that observed in the Q sludge. However, there was no mention of further attempts to identify these bacteria (31).

P sludge.

The dominance of the P sludge by β-proteobacteria (45%) and actinobacteria (35%) implicates them in EBPR. More specifically, the β-proteobacteria in the P sludge are likely all from the β-2 subgroup. β-Proteobacteria have been prominent in other EBPR sludges analyzed by FISH (29, 51), and they are well represented in cloned DNA extracted from sludge (11). However, β-proteobacteria are prominent in many activated sludges, irrespective of the P removal performance. In conventional carbon removal activated-sludge plants (25, 26) and EBPR reactors (26, 27), the dominant ubiquinone extracted was Q-8, which is from β-proteobacteria. While β-proteobacteria are commonly present in activated sludge, it is likely that different types of β-proteobacteria inhabit sludges with differing operational performances. For example, β-1-proteobacteria were detected in large numbers in a municipal sewage treatment plant which did not employ an EBPR process (1, 46), and the Q sludge, another non-P-removing sludge, was dominated by β-proteobacteria from groups other than β-1 or β-2. β-2-Proteobacteria dominated the P sludge (55%), suggesting that they are the β subgroup important to EBPR. This is in agreement with another study of EBPR sludge, in which a large proportion of the clones from a 16S ribosomal DNA clone library were represented by sequences of the Rhodocyclus group (11), which is in the β-2 subgroup of the proteobacteria.

There were more β-2-proteobacteria (55%) than β-proteobacteria (45%) in the P sludge (Fig. 3), but this could be due to the rather wide specificity of the BTWO23a probe, which was originally designed as a competitor probe for BONE23a (1). BTWO23a has the most sequence matches with β-2-proteobacteria (1) such as Azoarcus, Thauera, and Rhodocyclus spp. and some autotrophic ammonia oxidizers, but matches also occur with β-3-proteobacteria, (Nitrosovibrio tenuis) (1), some γ-proteobacteria (Chromatium spp.), and a couple of green nonsulfur bacteria.

The strong fluorescence signal from actinobacteria suggests they were active in the P sludge, and they could be PAOs. Other researchers also found that actinobacteria comprised a large proportion of bacteria in EBPR sludge, as determined by FISH (29, 51), by respiratory quinone profiles (27), and by clone library analysis (17). Additionally, a range of actinobacterial isolates has been investigated for phosphate accumulation (6, 39, 40, 48). It will be worthwhile to follow up on the role of actinobacteria in EBPR.

Large clusters of coccobacilli identified as β-2-proteobacteria (Fig. 4A) matched the morphology and arrangement of those clusters which stained positively for polyphosphate by the use of methylene blue stain. This does not concur with other EBPR studies, in which the morphology and arrangement of actinobacteria matched those containing polyphosphate (29, 51).

A variety of operational changes were made to the SBR before EBPR occurred. These included operating without pH control in the anaerobic periods, reseeding the reactor, adding peptone to the feed, and shortening the anaerobic period. Any one of these changes, or none of them, could have been responsible for initiation of EBPR, since EBPR did not commence for 110 days after the reactor was restarted. Further investigation of the conditions that lead to efficient EBPR is required.

Conclusions.

The phenotypes of the GAO (Q sludge)- and PAO (P sludge)-enriched cultures generated in the SBR were well understood because the carbon and phosphorus transformations of the mixed cultures were thoroughly monitored. The microbial community structures were quantitatively measured by non-culture-dependent methods (FISH probing and cell staining). Therefore, it was possible to presumptively assign phenotypes to specific microbial community members in the enriched cultures. β-2-Proteobacteria and possibly actinobacteria are PAOs, and β-proteobacteria from subgroups other than β-1 or β-2 are GAOs.

Selection strategies that led to changes in the bacterial populations and improved P removal included reseeding the reactor and applying pH stress in the anaerobic periods. Further investigation of the relationship between pH and the anaerobic transformations of EBPR is recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the CRC for Waste Management and Pollution Control Ltd., a center established and supported under the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program.

We appreciate the assistance and expertise provided by Colin Macqueen (Vision, Touch and Hearing Research Centre) in the application of the confocal laser scanning microscope at The University of Queensland. We are grateful to Philip Hugenholtz for providing valuable criticism of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R, Snaidr J, Wagner M, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. In situ visualization of high genetic diversity in a natural microbial community. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3496–3500. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3496-3500.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and Water Pollution Control Federation. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 18th ed. Baltimore, Md: Port City Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appeldoorn L J, Kortstee G, Zehnder A J B. Biological phosphate removal by activated sludge under defined conditions. Water Res. 1992;26:453–460. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bark K, Kämpfer P, Sponner A, Dott W. Polyphosphate-dependent enzymes in some coryneform bacteria isolated from sewage sludge. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;107:133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnard J L. Cut P and N without chemicals. Water Wastes Eng. 1974;11:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnard J L. A review of biological phosphorus removal in the activated sludge process. Water S A. 1976;2:136–144. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beacham A M, Seviour R J, Lindrea K C, Livingston I. Genospecies diversity of Acinetobacterisolates obtained from a biological nutrient removal pilot plant of a modified UCT configuration. Water Res. 1990;24:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackall L L, Rossetti S, Christenssen C, Cunningham M, Hartman P, Hugenholtz P, Tandoi V. The characterization and description of representatives of “G” bacteria from activated sludge plants. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;25:63–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bond P L, Hugenholtz P, Keller J, Blackall L L. Bacterial community structures of phosphate-removing and non-phosphate-removing activated sludges from sequencing batch reactors. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1910–1916. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.5.1910-1916.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braunegg G, Sonnleitner B, Lafferty R M. A rapid gas chromatographic method for the determination of poly-β-hydroxybutyric acid in microbial biomass. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1978;6:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brosius J, Dull T L, Steeter D D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchan L. Possible biological mechanism of phosphorus removal. Water Sci Technol. 1983;15:87–103. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cech J S, Hartman P. Competition between polyphosphate and polysaccharide accumulating bacteria in enhanced biological phosphate removal systems. Water Res. 1993;27:1219–1225. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cech J S, Hartman P. Glucose induced break down of enhanced biological phosphate removal. Environ Technol. 1990;11:651–656. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensson M, Blackall L L, Welander T. Metabolic transformations and characterisation of the sludge community in an enhanced biological phosphorus removal system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;49:226–234. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloete T E, Steyn P L. A combined fluorescent antibody-membrane filter technique for enumerating Acinetobacter in activated sludge. In: Ramadori R, editor. Biological phosphate removal from wastewaters. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1987. pp. 335–338. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davelaar D, Davies T R, Wiechers S G. The significance of an anaerobic zone for the biological removal of phosphate from wastewater. Water S A. 1978;4:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan A, Vasiliadis G E, Bayly R C, May J W, Raper W G C. Genospecies of Acinetobacterisolated from activated sludge showing enhanced removal of phosphate during pilot-scale treatment of sewage. Biotechnol Lett. 1988;10:831–836. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuhs G W, Chen M. Microbiological basis of phosphate removal in the activated sludge process for the treatment of wastewater. Microb Ecol. 1975;2:119–138. doi: 10.1007/BF02010434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glöckner F O, Amann R, Alfreider A, Pernthaler J, Psenner R, Trebesius K, Schleifer K-H. An in situhybridisation protocol for detection and identification of planktonic bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartley K J, Sickerdick L. Performance of Australian BNR plants. Presented at the Second Australian Conference on Biological Nutrient Removal from Wastewater. 1994. , Albury, Victoria, 4 to 6 October 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hicks R E, Amann R I, Stahl D A. Dual staining of natural bacterioplankton with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and fluorescent oligonucleotide probes targeting kingdom-level 16S rRNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2158–2163. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2158-2163.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hiraishi A. Respiratory quinone profiles as tools for identifying different bacterial populations in activated sludge. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1988;34:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiraishi A, Masamune K, Kitamura H. Characterization of the bacterial population structure in an anaerobic-aerobic activated sludge system on the basis of respiratory quinone profiles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:897–901. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.4.897-901.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hiraishi A, Morishima Y. Capacity for polyphosphate accumulation of predominant bacteria in activated sludge showing enhanced phosphate removal. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;69:368–371. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkins D, Richard M G, Daigger G T. Manual on the causes and control of activated sludge bulking and foaming. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kämpfer P, Erhart R, Beimfohr C, Bohringer J, Wagner M, Amann R. Characterization of bacterial communities from activated sludge—culture-dependent numerical identification versus in situ identification using group- and genus-specific rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Microb Ecol. 1996;32:101–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00185883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lathe R. Synthetic oligonucleotide probes deduced from amino acid sequence data. Theoretical and practical considerations. J Mol Biol. 1985;183:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W-T, Mino T, Nakamura K, Matsuo T. Glycogen accumulating population and its anaerobic substrate uptake in anaerobic-aerobic activated sludge without biological phosphorus removal. Water Res. 1996;30:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W-T, Mino T, Matsuo T, Nakamura K. Biological phosphorus removal processes—effect of pH on anaerobic substrate metabolism. Water Sci Technol. 1996;30:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W-T, Mino T, Nakamura K, Matsuo T. Role of glycogen in acetate uptake and polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis in anaerobic-aerobic activated sludge with a minimized polyphosphate content. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;5:535–540. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manz W, Amann R, Ludwig W, Wagner M, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic oligonucleotide probes for the major subclasses of Proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manz W, Wagner M, Amann R, Schleifer K-H. In situcharacterization of the microbial consortia active in two wasterwater treatment plants. Water Res. 1994;28:1715–1723. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mino T, Arun V, Tsuzuki Y, Matsuo T. Effect of phosphorus accumulation on acetate metabolism in the biological phosphorus removal process. In: Ramadori R, editor. Biological phosphate removal from wastewaters. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1987. pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mino T, Liu W T, Kurisu F, Matsuo T. Modelling glycogen storage and denitrification capability of microorganisms in enhanced biological phosphate removal processes. Water Sci Technol. 1995;31:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray R G E, Doetsch R N, Robinow C F. Determinative and cytological light microscopy. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura K, Hiraishi A, Yoshimi Y, Kawaharasaki M, Masuda K, Kamagata Y. Microlunatus phosphovorusgen. nov., sp. nov., a new gram-positive polyphosphate-accumulating bacterium isolated from activated sludge. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:17–22. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura K, Masuda K, Mikami E. Isolation of a new type of polyphosphate accumulating bacterium and its phosphate removal characteristics. J Ferment Bioeng. 1991;71:258–263. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roller C, Wagner M, Amann R, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. In situprobing of gram-positive bacteria with high DNA G+C content using 23S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides. Microbiology. 1994;140:2849–2858. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Satoh H, Mino T, Matsuo T. Deterioration of enhanced biological phosphorus removal by the domination of microorganisms without polyphosphate accumulation. Water Sci Technol. 1994;30:203–211. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satoh H, Mino T, Matsuo T. Uptake of organic substrates and accumulation of polyhydroxyalkanoates linked with glycolysis of intracellular carbohydrates under anaerobic conditions in the biological excess phosphate removal processes. Water Sci Technol. 1992;26:933–942. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smolders G J F. Ph.D. dissertation. Delft, The Netherlands: University of Technology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smolders G J F, van der Meij J, van Loosdrecht M C M, Heijnen J J. Model of the anaerobic metabolism of the biological phosphorus removal process—stoichiometry and pH influence. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1994;43:461–470. doi: 10.1002/bit.260430605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snaidr J, Amann R, Huber I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic analysis and in situ identification of bacteria in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2884–2896. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2884-2896.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toerien D F, Gerber A, Lötter L H, Cloete T E. Enhanced biological phosphorus removal in activated sludge systems. Adv Microb Ecol. 1990;11:173–230. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ubukata Y, Takii S. Induction method of excess phosphate accumulation for phosphate removing bacteria isolated from anaerobic/aerobic activated sludge. Water Sci Technol. 1994;28-6:221–227. [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Loosdrecht M C M, Smolders G J, Kuba T, Heijnen J J. Metabolism of microorganisms responsible for enhanced biological phosphorus removal from wastewater. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1997;71:109–116. doi: 10.1023/a:1000150523030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner M, Amann R, Lemmer H, Schleifer K-H. Probing activated sludge with oligonucleotides specific for proteobacteria: inadequacy of culture-dependent methods for describing microbial community structure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1520–1525. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1520-1525.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagner M, Erhart R, Manz W, Amann R, Lemmer H, Wedi D, Schleifer K-H. Development of an rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe specific for the genus Acinetobacterand its application for in situ monitoring in activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:792–800. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.792-800.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wentzel M C, Loewenthal R E, Ekama G A, Marais G v R. Enhanced polyphosphate organism cultures in activated sludge systems. Part 1. Enhanced culture development. Water S A. 1988;14:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wentzel M C, Lötter L H, Ekama G A, Loewenthal R E, Marais G v R. Evaluation of biochemical models for biological excess phosphate removal. Water Sci Technol. 1991;23:567–576. [Google Scholar]