Abstract

Objective:

To determine the minimum duration of electroencephalography (EEG) data necessary to differentiate EEG features of Lewy body dementia (LBD), i.e., dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia, from non-LBD patients, i.e., Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease.

Methods:

We performed quantitative EEG analysis for 16 LBD and 14 non-LBD patients. After artifact removal, Fast Fourier Transform was performed on 90, 60 and 30 2-second epochs to derive dominant frequency (DF); dominant frequency variability (DFV); and dominant frequency prevalence (DFP).

Results:

In LBD patients, there were no significant differences in EEG features derived from 90, 60 and 30 2-second epochs (all p>0.05). There were no significant differences in EEG features derived from three different groups of 30 2-second epochs (all p>0.05). When analyzing EEG features derived from 90 2-second epochs, we found that LBD had significantly reduced DF, reduced DFV, and reduced DFP alpha compared to the non-LBD group (all p<0.05). These same differences were observed between the LBD and non-LBD groups when analyzing 30 2-second epochs.

Conclusions:

There were no differences in EEG features derived from 1 minute versus 3 minutes of EEG data, and both durations of EEG data equally differentiated LBD from non-LBD.

Keywords: Lewy body dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson disease dementia, electroencephalography, biomarker

Introduction

Together, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson disease dementia (PDD), which share same neuropathology, clinical manifestations, and treatment,1,2 comprise Lewy body dementia (LBD). LBD is the second most common cause of dementia after Alzheimer disease (AD) and is associated with accelerated cognitive decline, greater caregiver burden, and higher healthcare costs.3,4 Individuals with LBD suffer from delays in appropriate care due to delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis. Accurate and early diagnosis of LBD is a major gap in LBD care and closing this gap will ensure that patients receive appropriate care.

Quantitative analysis of electroencephalography (QEEG) has emerged as potential biomarker of LBD. QEEG can be performed on standard electroencephalography (EEG) arrays of 16–21 EEG electrodes. EEG features associated with cognitive decline in Parkinson disease (PD) include an increase in the slower (<8Hz) delta and theta ranges and a decrease in the faster (>8Hz) alpha, beta and gamma bands in the occipito-parietal-temporal regions.5 Changes in the EEG can be seen 2–7 years prior to cognitive decline in PD and so are predictive of PDD.6 Similar EEG features have been also described in DLB,7 and “prominent posterior slow-wave activity on EEG with periodic fluctuations in the pre-alpha/theta range” were added as a supportive biomarker of DLB in the 2017 DLB criteria.8 In summary, there is accumulating evidence that LBD patients exhibit characteristic EEG features, and these data support use of EEG as a diagnostic biomarker for LBD.

Despite this accumulating evidence, EEG is rarely used clinically to support the diagnosis of LBD.9 One of the potential reasons for this is that there have been multiple methodological differences in previous studies. One of these differences is that prior QEEG studies in LBD have used variable durations of EEG data to derive EEG features. While longer durations of EEG are often collected, the most commonly used maximum length of time of analyzed EEG signal is 3 minutes.7,10,11 Many studies have analyzed shorter amounts of EEG data, one as little as 20 seconds.12 Establishing a minimal duration of EEG data necessary to derive stable, differentiating EEG features of LBD would increase the likelihood of collecting artifact-free EEG and support broader application of this biomarker. The overall objective of this study was to determine if one minute of EEG data is sufficient to differentiate LBD from patients without LBD. To accomplish this, we 1) compared EEG features of LBD patients from 1, 2 and 3 minutes of EEG data, and 2) determined if one minute of EEG data could differentiate LBD from patients without LBD as well as 3 minutes of EEG data.

Methods

Study Participants

Prior to study initiation, the Human Research Protection Program/Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University approved the conduct of this retrospective cohort study. We used the TriNetX platform to identify patients with clinical encounters between 2010 and 2020 at Virginia Commonwealth University Health System who 1) had ICD-10-CM diagnostic codes for Alzheimer’s disease (G30), Parkinson disease (G20), or dementia with Lewy bodies (G31.83) and 2) had a clinical EEG. Age was restricted between 50 and 90 years old. This resulted in 201 potential Alzheimer’s disease patients and 157 patients with Parkinson disease or dementia with Lewy bodies who had EEGs.

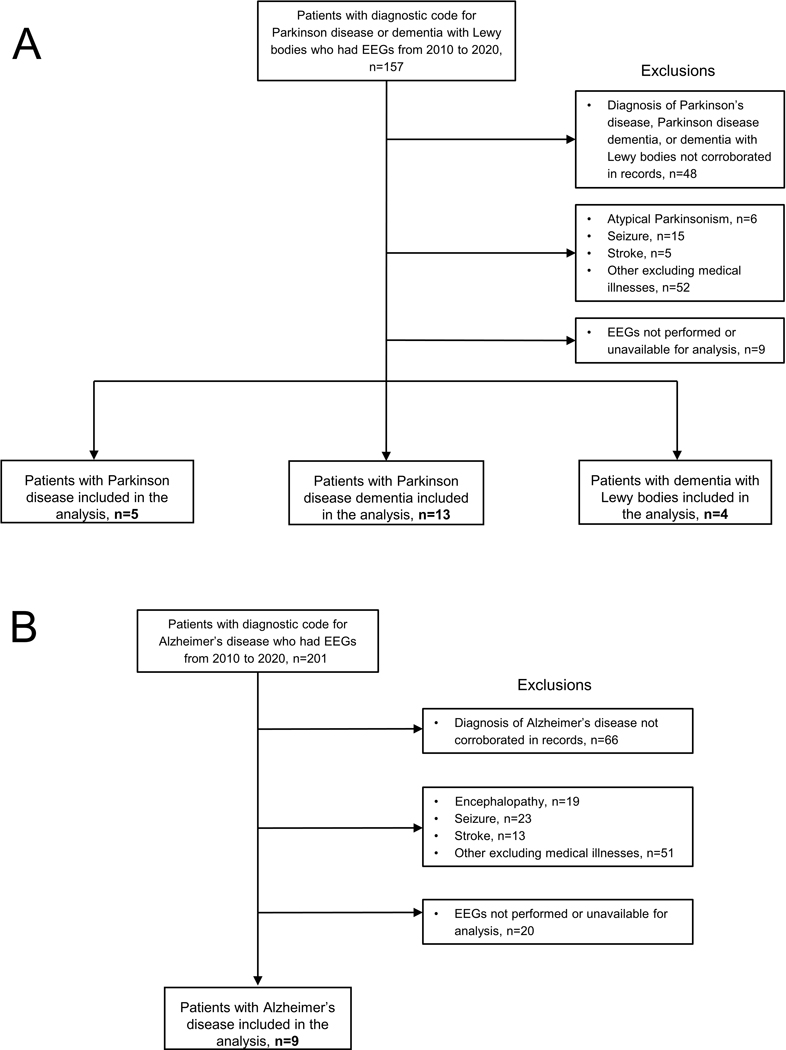

Patient charts, including all clinical notes, were screened to exclude or corroborate the clinical diagnosis of AD, PD, or LBD (PDD and DLB). Patient records indicating health conditions that could affect EEG data were excluded. Reasons for exclusion included atypical parkinsonism, encephalopathy, seizures, stroke, and other potentially confounding medical conditions. For patients whose indication for EEG was an episode of altered responsiveness or altered mental status, only EEGs acquired after resolution of the episode were included and none were treated with rescue benzodiazepines during the EEG. Following screening, EEGs for 9 AD patients, 5 PD patients, 13 PDD patients, and 4 DLB patients were available for analysis. See Figure 1. We confirmed diagnosis based on neurology clinical notes and extracted the following information: age at EEG, sex, scheduled medications at time of EEG, purpose of EEG, and any cognitive data or information about cognitive status. We excluded patients whose diagnosis of AD, PD, LBD (PDD and DLB) could not be corroborated from the clinic notes. No scheduled medications were withdrawn prior to EEG recordings.

Figure 1. Participant Selection Diagram.

Flow diagrams for selection of A) patients with Parkinson disease, Parkinson disease dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies and B) Alzheimer’s disease.

EEG acquisition

EEGs were collected using Natus XLTEK (Natus Medical Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA) systems by registered EEG technicians with subjects laying supine in a low-lit, quiet room. Subjects had 19 silver-silver chloride scalp electrodes placed according to the International 10–20 System with standard reference/ground placement, impedance <5kOhm sampled at 256 Hz, and low frequency filter (LFF)=1Hz, high frequency filter (HFF)=70Hz, and with a 60Hz notch filter. Additional eye, ear, and electrocardiogram leads were also collected. EEG was acquired as continuous signal for approximately 30 minutes with subjects resting comfortably with their eyes closed in a quiet room. EEG was acquired from Fp1, Fp2, Fz, F3, F4, F7, F8, Cz, C3, C4, Pz, P3, P4, T3, T4, T5, T6, O1 and O2.

EEG Analysis

EEG inspection, epoch selection, and analysis were performed blinded to clinical diagnosis. EEG studies were independently reviewed by a board certified epileptologist using Natus NeuroWorks 9 and Persyst 12 (Persyst Development Corp., Solana Beach, CA, USA) software. EEGs were first visually inspected to ensure subjects’ background activity captured only awake patterns with minimal myogenic, eyeblink or other environmental artifacts. Periods of drowsiness were excluded by monitoring for background changes and slow eye movements of drowsiness during the course of the recording. EEGs were reviewed in full to exclude studies that captured polymorphic mixed delta/theta slowing, discontinuity or disorganization which would be attributable to delirium or encephalopathy from infectious, metabolic or toxic etiologies. Segments of awake EEG with minimal artifacts were then exported to European Data Format (*.EDF) format with options set to pad gaps with zeros.

EEGs were then processed using the EEGLAB toolbox (Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience) in MATLAB R2020b (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, Massachusetts, USA). EEGs were divided into 90 2-second non-overlapping epochs. The obtained epochs were visually inspected and any epochs with remaining artifacts were discarded. For analysis, the initial 90 2-second artifact-free epochs were selected. Two participants with less than 90 usable epochs, i.e., one AD participant with 73 and one PDD participant with 82 2-second epochs, were included in all analyses. One PDD participant with only 60 usable epochs was excluded from analyses because only 60 epochs precluded even partial analysis of a third group of 30 epochs in this participant.

Using MATLAB R2020b, Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) with a frequency resolution of 0.5 Hz was performed on each epoch and each electrode and absolute power spectral density was estimated. Absolute power spectra values were transformed to relative power spectral density for each epoch and each electrode. Power spectrum was divided into 4 frequency bands: delta (3–3.5 Hz), theta (4–5.5 Hz), pre-alpha (6–7.5 Hz), and alpha (8–13 Hz).7,10 Dominant frequency (DF) for each epoch was defined as the frequency with the greatest power. Dominant frequency variability (DFV) represents the variability of dominant frequency across analyzed epochs and is calculated as the standard deviation of mean dominant frequency across the analyzed epochs. Dominant frequency prevalence (DFP), defined as the percentage of epochs showing a specific frequency band, was then calculated for each electrode. EEG features from individual channels were grouped to define derivations as follows: anterior (Fp1, Fp2, Fz, F3, F4, F7, F8), posterior (Pz, P3, P4, O1, O2) and temporal (T3, T4, T5, T6). The above procedure was performed on all 90 epochs and the first 30 epochs in all participants. In the LBD group, we also analyzed the first 60 epochs, the second 30 epochs, and the third 30 epochs.

Statistical Analysis

Values for DF, DFV, and DFP were reported as medians with interquartile ranges. We adopted non-parametric statistical tools as the sample size is smaller than what asymptotic normality requires. Next, using Friedman test, we evaluated whether there were differences in DF, DFV, and DFP in the LBD group depending on whether these values were derived from analysis of 90 epochs (1–90), the first 60 epochs (1–60), or the first 30 epochs (1–30). Here the goal is to demonstrate the stability of the markers against length of epochs. In another analysis we evaluated the differences in these values in the first 30 epochs (1–30), the second 30 epochs (31–60), and the third 30 epochs (61–90). For the next set of analyses, participants were considered in 2 groups: LBD (PDD and DLB) and non-LBD (AD and PD). For the purpose of this methodological investigation, we have labeled the AD and PD group as non-LBD but recognize that other disorders would need to be included to establish the diagnostic utility of an EEG biomarker. DF, DFV and DFP were compared between the 2 groups for each derivation using Mann-Whitney U tests. This was repeated for the comparison of the first 30 epochs in each group. Effect size (Cohen’s d) was reported for each difference. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using StataIC14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.).

Results

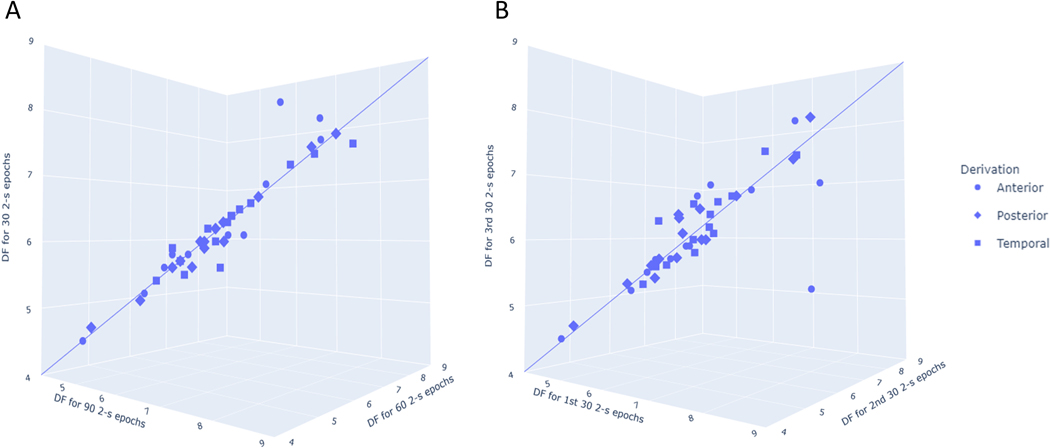

LBD and non-LBD (AD and PD) participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. For the first set of analyses, we excluded the PDD participant with 82 2-second epochs. We first compared the DF, DFV and DFP values derived from analyzing 90 2-second epochs, 60 2-second epochs and 30 2-second epochs in the LBD group. There were no statistically significant differences among any of the EEG features (Supplementary Table 1; Figure 2A). Similarly, there were no significant differences between any of the EEG features derived from the first 30 epochs (1–30), the second 30 epochs (31–60), and the third 30 epochs (61–90) in the LBD group (Supplementary Table 2; Figure 2B). Common threshold for 5% type I error was further restricted using Benjamini Hochberg false discovery rate to control for false positives. Applying this correction, there remained no significant differences in the EEG features derived from different groups of 2-second epochs.

Table 1.

Characteristic of LBD and non-LBD patients with clinical EEGs

| LBD (n=16) | Non-LBD (n=14) | PD (n=5) | AD (n= 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (I.Q.R.) | 76 (73.5–81) | 81.5 (64–83) | 64 (64–81) | 82.0 (78–87) |

| Gender, women n(%) | 6 (37.5) | 10 (71.4) | 4(80.0) | 6(66.7) |

| Inpatient EEG, n (%) | 9 (56.3) | 8 (57.1) | 2 (40.0) | 6 (66.7) |

| Year of EEG, median year (I.Q.R.) | 2016 (2015–2017) | 2016.5 (2015–2018) | 2017 (2016–2018) | 2016 (2015–2017) |

| Indication for EEG, n (%) | ||||

| Altered mental status | 7 (43.8) | 8 (57.1) | 1 (20) | 7 (77.78) |

| Episode of altered responsiveness | 4 (25.0) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (40) | 1 (11.11) |

| Other | 5 (31.3) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (40) | 1 (11.11) |

| Medication usage, n (%) | ||||

| Cholinesterase inhibitorsa | 9 (56.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) |

| Anticholinergic medicationsb | 0 (0) | 4 (28.6) | 0 (0) | 4 (44.4) |

| Benzodiazepines | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Antiepileptic medicationsc | 3 (18.8) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (40.0) | 1 (11.1) |

This includes donepezil, rivastigmine or galantamine

Oral anticholinergic medications with a score of 2 or 3 (definite anticholinergic effect) on the Anticholinergic Cognitive Burden Scale.24

This includes levetiracetam or gabapentin

Comparisons of age and year of EEG were performed with Mann-Whitney U tests and comparison of proportions was performed using Chi-squared tests. Abbreviations: EEG: electroencephalogram; I.Q.R: Interquartile range; LBD: Lewy body dementia.

Figure 2. 3-D plots of EEG dominant frequency values for different epoch selections in the Lewy body dementia group.

The 3-d plots show EEG dominant frequency values from analyses of (A) 90, 60, and 30 2-second epochs and (B) the first 30, second 30, and third 30 2-second epochs. An idealized line is plotted to demonstrate that for most individuals and derivations, there was little difference between dominant frequency values derived from analysis of different epoch selections. Visual inspection of the anterior derivation outlier in Figure 2B revealed a high number of blinking artifacts which likely differentially affected feature extraction. Abbreviations: DF: Dominant frequency.

The characteristics of AD and PD participants, which comprised the non-LBD comparison group, are summarized together in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the LBD and non-LBD groups in age, gender, and number of EEGs obtained in the inpatient setting (all p>0.05). Altered mental status and an episode of altered responsiveness were the most common indications for EEG, 68.8% of LBD patients and 78.5% of non-LBD patients.

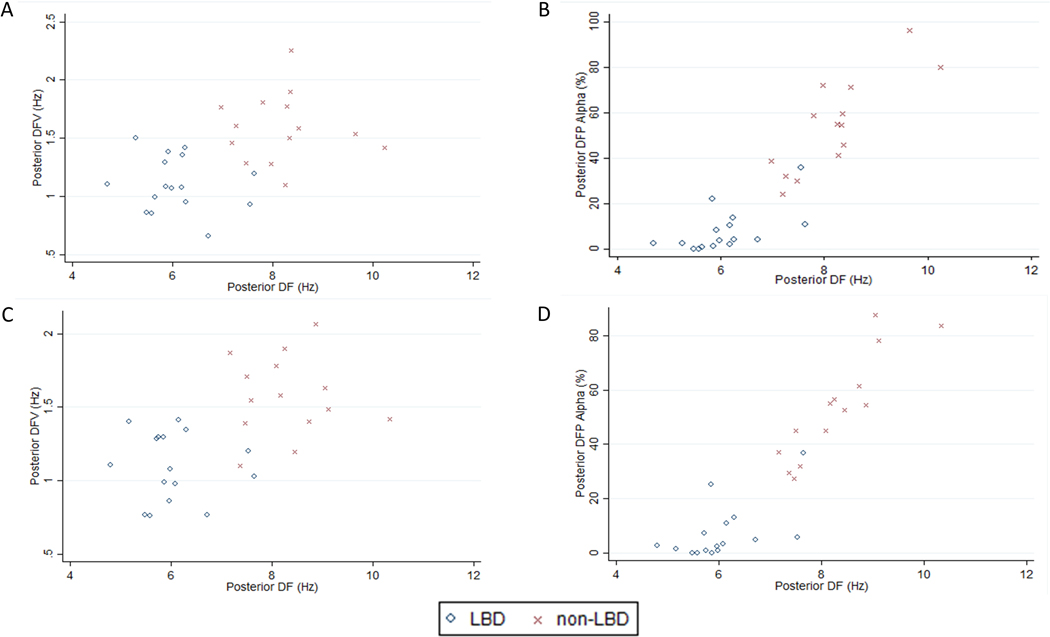

When considering EEG features derived from 90 2-second epochs, the LBD group had significantly reduced DF and DFV compared to the non-LBD group in all derivations (Table 2; Figure 3). Consistent with the significantly lower DF in the LBD group, the LBD group had reduced alpha activity and increased theta and delta activity compared to the non-LBD group. Application of the 5% false discovery rate (FDR) threshold did not alter the results for analysis of 90 2-second epochs. The findings were the same when LBD was compared to AD only (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4).

Table 2.

Quantitative EEG features from 90 2-second epochs for LBD and non-LBD patients

| Derivations | EEG Features | LBD (n=16) | Non-LBD (n=14) | Effect size | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | DF | 5.9 (5.6–6.6) | 8.0 (7.0–8.6) | 2.0 | 0.0001 |

| DFV | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) | 1.8 (1.7–2.2) | 1.7 | 0.0003 | |

| DFP | |||||

| Alpha | 9.7 (2.5–13.5) | 53.8 (29.5–62.4) | 2.3 | <0.0001 | |

| Pre-alpha | 41.9 (32.4–53.8) | 28.1 (9.8–39.2) | 0.6 | 0.0643 | |

| Theta | 37.9 (26.3–44) | 11.5 (6.2–20) | 1.5 | 0.0006 | |

| Delta | 10.8 (8.2–17.3) | 2.3 (0–8.4) | 1.2 | 0.0027 | |

| Posterior | DF | 6.1 (5.6–6.2) | 8.4 (7.3–8.4) | 2.6 | <0.0001 |

| DFV | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.8 | 0.0001 | |

| DFP | |||||

| Alpha | 5.7 (2–10.1) | 54.9 (40.7–72.2) | 3 | <0.0001 | |

| Pre-alpha | 48.4 (37.2–58.6) | 35.1 (18.7–43.5) | 0.8 | 0.0340 | |

| Theta | 36.8 (25.6–45.2) | 7.3 (3–14) | 2.0 | 0.0002 | |

| Delta | 8.5 (5–11.3) | 1.6 (0–4.2) | 1.2 | 0.0021 | |

| Temporal | DF | 6.3 (5.9–6.6) | 7.6 (7.3–9.3) | 1.8 | 0.0001 |

| DFV | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.8 (1.4–2.1) | 1.5 | 0.0014 | |

| DFP | |||||

| Alpha | 8 (3.6–16) | 46.3 (34.7–80.0) | 2.1 | <0.0001 | |

| Pre-alpha | 50.8 (35–66.9) | 39.4 (8.1–59.1) | 0.5 | 0.1574 | |

| Theta | 30 (19.5–42.6) | 7.7 (4.2–12) | 2.0 | 0.0003 | |

| Delta | 6.3 (3.9–13.6) | 1.8 (0–3.9) | 1.1 | 0.0029 |

DF and DFV are reported as median Hz with interquartile range in parentheses. FP is presented as median % of epochs with interquartile range in each frequency band.

Abbreviations: DF: Dominant frequency; DFV: Dominant frequency variability; EEG: Electroencephalogram; DFP: Dominant frequency prevalence; LBD: Lewy body dementia.

Figure 3. 2-D plots of posterior derivation quantitative EEG features in the Lewy body dementia and non-Lewy body dementia groups.

The scatterplots show the posterior dominant frequency and dominant frequency variability derived from analysis of (A) 90 epochs and (C) 30 epochs and the posterior dominant frequency and alpha dominant frequency prevalence derived from analysis of (B) 90 epochs and (D) 30 epochs for each individual in the Lewy body dementia group. Abbreviations: DF: Dominant frequency; DFV: Dominant frequency variability; DFP: Dominant frequency prevalence; LBD: Lewy body dementia.

Considering the EEG features derived from 30 2-second epochs, the findings were the same as the analyses of EEG features derived from 90 2-second epochs (Supplementary Table 5; Figure 3). When a 5% FDR threshold was applied, there was no significant difference between anterior pre-alpha DFP, temporal DFV and temporal pre-alpha DFP EEG features. All other EEG features were below the 5% FDR threshold. Comparison of EEG features derived from 30 2-second epochs in LBD and AD only revealed no differences in the results except that temporal DFV was not significantly different between the groups.

Discussion

Using different numbers of 2-second epochs of reconstructed artifact-free EEG data, we found no significant differences in the EEG features of LBD patients regardless of duration (1 minute, 2 minutes, or 3 minutes). We also found that the EEG features of LBD patients derived from different 1-minute segments of EEG data were not significantly different. This demonstrates that our method of analyzing artifact-free segments of awake EEG results in stable EEG features over time. This additionally verifies the presence of baseline awake activity and absence of disorganized, polymorphic activity that would be a confounder due to an active encephalopathic state. Consistent with prior studies, we found that quantitative EEG features of DF, DFV, and DFP were significantly different between LBD and non-LBD groups.7,10,13 In keeping with the stability of EEG features between both 3 minutes and 1 minute of EEG data, we found that the significant differences observed between LBD and non-LBD groups with 3 minutes of EEG data were also found with 1 minute of EEG data.

A 2021 systematic review of EEG studies in DLB identified multiple methodological differences in previously reported studies.13 One of the prominent differences between studies is the length of EEG segments that are collected and analyzed. A number of studies analyzed 3 minutes of EEG data,7,10,11,14,15 some of which divided the data into 2-second epochs as we did in the current study.7,10,11 A number of studies used less than 3 minutes of EEG data, from 140 seconds16 to as little as 20 seconds.12 A third group of studies did not specify the duration of EEG data that was analyzed.17–19 Our study provides evidence that as little as 1 minute of EEG data captures the same EEG features as longer segments and 1 minute of EEG data is as good as longer segments in differentiating LBD from other disease groups.

Based on prior studies,13 “prominent posterior slow-wave activity on EEG with periodic fluctuations in the pre-alpha/theta range” was included as a supportive biomarker in the 2017 DLB criteria,8 and PDD is also associated with prominent posterior slow-wave activity.10,17,20 We found significant differences between LBD and non-LBD groups in DF, DFV, and DFP in all derivations. Similar to other studies,7,10 we found that the greatest differences between groups were observed in the posterior derivation. Significant differences were also seen in the anterior and temporal derivations in all EEG features except DFP in the pre-alpha frequency band. To ensure that PD patients included in the non-LBD group did not influence our findings, we analyzed the differences in EEG features between LBD and AD alone and found the same differences between groups in the posterior derivation. DFV in the temporal was no longer significantly different between groups, likely a result of lost power due to the smaller sample size.

We found that DFV was reduced in the LBD group compared to the non-LBD group. This is in contrast to a previous study which reported increased DFV in LBD patients compared to AD.10 The discrepancy is likely due to differences in the methods used to calculate DFV: the prior study reported DFV as the range of DF from the Compressed Spectral Array,10 while we calculated DFV as the standard deviation of the mean DF across analyzed epochs. Other studies which applied the same method as ours also reported reduced DFV in LBD compared to AD.21,22

Limitations of our study are that we investigated a clinical cohort which did not have a standardized diagnostic evaluation and did not have corroborating biomarker data for a diagnosis of AD. To minimize the impact of comorbid conditions on our findings, we rigorously excluded all patients who may have had medical comorbidities that could influence their EEG. Despite our efforts, all participants had EEGs ordered for a clinical indication, a potential source of selection bias, and EEGs may still have been affected by conditions other than LBD. To avoid sources of selection bias inherent in a clinical cohort of LBD, AD, and PD patients referred for EEG, future studies should seek to prospectively collect standardized clinical and EEG assessments in these patient groups. More than half of the EEGs we analyzed were obtained on hospitalized inpatients. This setting introduces possible artifacts and environmental distractions. For our purposes, distractions would have promoted wakefulness which is what we sought to capture. The initial blinded review of EEG data, which excluded pathologic slowing suggestive of encephalopathy (variable amplitude/frequency delta/theta slowing), also was used to ensure awake EEGs were obtained. Despite starting with a much larger clinical population, our small sample size is a limitation of the study. Lastly, we cannot exclude that PD participants had mild cognitive impairment. Our stringent exclusion criteria likely selected for a group of patients with more certain clinical diagnoses and thus likely explains our ability to discriminate LBD from non-LBD with a limited number of EEG features. For our purposes, these well-defined groups supported our ability to address our primary research objectives.

Specific EEG features derived from quantitative analysis are a promising biomarker for diagnosis of LBD. If EEG is validated as a biomarker of LBD, it will support accurate and early diagnosis, which has current implications for treatment.1,2,23 The major contribution of this study is that we provide evidence that quantitative analysis of as little as 1 minute of EEG data provides the same results as analysis of longer segments of EEG and the EEG features derived from one minute of EEG data are stable over time. Our findings support the idea that 1 minute of artifact-free EEG data is sufficient to differentiate LBD in the clinical setting from the common alternative diagnoses of AD and PD. Establishing that 1 minute of awake, artifact-free EEG is sufficient to derive stable, differentiating EEG features of LBD supports its more widespread adoption as a clinical biomarker.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This study received funding support from the NIH (1R21AG077469), the C. Kenneth and Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research grant (UL1TR002649) and the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine via the Dean’s Summer Research Fellowship (L.J.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Stinton C, McKeith I, Taylor JP, et al. Pharmacological Management of Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJP. 2015;172(8):731–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connors MH, Quinto L, McKeith I, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for Lewy body dementia: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2018;48(11):1749–1758. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller C, Ballard C, Corbett A, Aarsland D. The prognosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. The Lancet Neurology. 2017;16(5):390–398. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30074-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Wilson L, Kornak J, et al. The costs of dementia subtypes to California Medicare fee-for-service, 2015. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019;15(7):899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cozac VV, Gschwandtner U, Hatz F, Hardmeier M, Rüegg S, Fuhr P. Quantitative EEG and Cognitive Decline in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s Disease. 2016;2016:e9060649. doi: 10.1155/2016/9060649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klassen BT, Hentz JG, Shill HA, et al. Quantitative EEG as a predictive biomarker for Parkinson disease dementia. Neurology. 2011;77(2):118–124. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318224af8d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonanni L, Franciotti R, Nobili F, et al. EEG Markers of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Multicenter Cohort Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(4):1649–1657. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88–100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong MJ, Irwin DJ, Leverenz JB, Gamez N, Taylor A, Galvin JE. Biomarker Use for Dementia With Lewy Body Diagnosis: Survey of US Experts. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2021;35(1):55–61. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonanni L, Thomas A, Tiraboschi P, Perfetti B, Varanese S, Onofrj M. EEG comparisons in early Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia patients with a 2-year follow-up. Brain. 2008;131(3):690–705. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonanni L, Perfetti B, Bifolchetti S, et al. Quantitative electroencephalogram utility in predicting conversion of mild cognitive impairment to dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurobiology of Aging. 2015;36(1):434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garn H, Coronel C, Waser M, Caravias G, Ransmayr G. Differential diagnosis between patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease dementia, or dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal dementia, behavioral variant, using quantitative electroencephalographic features. J Neural Transm. 2017;124(5):569–581. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1699-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatzikonstantinou S, McKenna J, Karantali E, Petridis F, Kazis D, Mavroudis I. Electroencephalogram in dementia with Lewy bodies: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(5):1197–1208. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01576-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engedal K, Snaedal J, Hoegh P, et al. Quantitative EEG Applying the Statistical Recognition Pattern Method: A Useful Tool in Dementia Diagnostic Workup. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2015;40(1–2):1–12. doi: 10.1159/000381016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira D, Jelic V, Cavallin L, et al. Electroencephalography Is a Good Complement to Currently Established Dementia Biomarkers. DEM. 2016;42(1–2):80–92. doi: 10.1159/000448394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caviness JN, Utianski RL, Hentz JG, et al. Differential spectral quantitative electroencephalography patterns between control and Parkinson’s disease cohorts. European Journal of Neurology. 2016;23(2):387–392. doi: 10.1111/ene.12878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babiloni C, Del Percio C, Lizio R, et al. Abnormalities of cortical neural synchronization mechanisms in patients with dementia due to Alzheimer’s and Lewy body diseases: an EEG study. Neurobiology of Aging. 2017;55:143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roks G, Korf ESC, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Stam CJ. The use of EEG in the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2008;79(4):377. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.125385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liedorp M, Van Der Flier WM, Hoogervorst ELJ, Scheltens P, Stam CJ. Associations between Patterns of EEG Abnormalities and Diagnosis in a Large Memory Clinic Cohort. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2009;27(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caviness JN, Hentz JG, Evidente VG, et al. Both early and late cognitive dysfunction affects the electroencephalogram in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2007;13(6):348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peraza LR, Cromarty R, Kobeleva X, et al. Electroencephalographic derived network differences in Lewy body dementia compared to Alzheimer’s disease patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4637. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22984-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stylianou M, Murphy N, Peraza LR, et al. Quantitative electroencephalography as a marker of cognitive fluctuations in dementia with Lewy bodies and an aid to differential diagnosis. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2018;129(6):1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2018.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor JP, McKeith IG, Burn DJ, et al. New evidence on the management of Lewy body dementia. The Lancet Neurology. 2020;19(2):157–169. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30153-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boustani M, Campbell N, Munger S, Maidment I, Fox C. Impact of anticholinergics on the aging brain: a review and practical application. Aging Health. 2008;4(3):311–320. doi: 10.2217/1745509X.4.3.311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.