Abstract

Background

Advancement in breast cancer (BC) diagnosis and treatment have increased the number of long-term survivors. Consequently, primary BC survivors are at a greater risk of developing second primary cancers (SPCs). The risk factors for SPCs among BC survivors including sociodemographic characteristics, cancer treatment, comorbidities, and concurrent medications have not been comprehensively examined. The purpose of this study is to assess the incidence and clinicopathologic factors associated with risk of SPCs in BC survivors.

Methods

We analyzed 171, 311 women with early-stage primary BC diagnosed between January 2000 and December 2015 from the Medicare-linked Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER-Medicare) database. SPC was defined as any diagnosis of malignancy occurring within the study period and at least 6 months after primary BC diagnosis. Univariate analyses compared baseline characteristics between those who developed a SPC and those who did not. We evaluated the cause-specific hazard of developing a SPC in the presence of death as a competing risk.

Results

Of the study cohort, 21,510 (13%) of BC survivors developed a SPC and BC was the most common SPC type (28%). The median time to SPC was 44 months. Women who were white, older, and with fewer comorbidities were more likely to develop a SPC. While statins [hazard ratio (HR) 1.066 (1.023–1.110)] and anti-hypertensives [HR 1.569 (1.512–1.627)] increased the hazard of developing a SPC, aromatase inhibitor therapy [HR 0.620 (0.573–0.671)] and bisphosphonates [HR 0.905 (0.857–0.956)] were associated with a decreased hazard of developing any SPC, including non-breast SPCs.

Conclusion

Our study shows that specific clinical factors including type of cancer treatment, medications, and comorbidities are associated with increased risk of developing SPCs among older BC survivors. These results can increase patient and clinician awareness, target cancer screening among BC survivors, as well as developing risk-adapted management strategies.

Keywords: Breast cancer survivors, Second primary cancer, Aromatase inhibitor, Comorbidities, Medications

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) accounts for nearly one in three cancer cases diagnosed in women [1]. Early detection as well as improved management have contributed to the increase in survival rates of BC patients. As a result, longer life expectancy is accompanied by increased risk of developing a second primary cancer (SPC), defined as malignant tumors with differing pathologic morphologies, and are not metastases from the initial primary cancer [1, 2].

The incidence of SPCs among women with primary BC have been inconclusive, ranging from 4 to 17%, with varying follow up times [1]. Though prior studies show that BC survivors are more susceptible to developing a SPC [3, 4], it has been difficult to quantify that risk, and identify specific factors that may predispose some BC survivors to developing SPCs. The American Cancer Society recommends annual mammography screenings for the general population as well as specific guidelines for those with a family history of BC or women with genetic mutations. However, there is currently not enough evidence for specific BC screening recommendations based on having a personal history of BC. There are also no comprehensive screening guidelines for other types of cancers in BC survivors.

The purpose of this study is to (1) assess the incidence and types of SPCs among an extensive cohort of older BC survivors and (2) identify clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with the development of SPCs. Our study will aid in improving clinician and patient awareness of SPCs in BC survivors and guide discussions for developing risk-adapted management strategies.

Materials and methods

Data sources

Study participants were selected from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results registry linked to Medicare claims record (SEER-Medicare). We excluded individuals in healthcare maintenance organizations (HMOs) and those without Medicare Parts A and B insurance, due to incomplete claims which are needed to assess comorbidities and cancer treatment (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy). We excluded individuals without Medicare Part D claims data which were needed to ascertain prescription medication use.

Study population

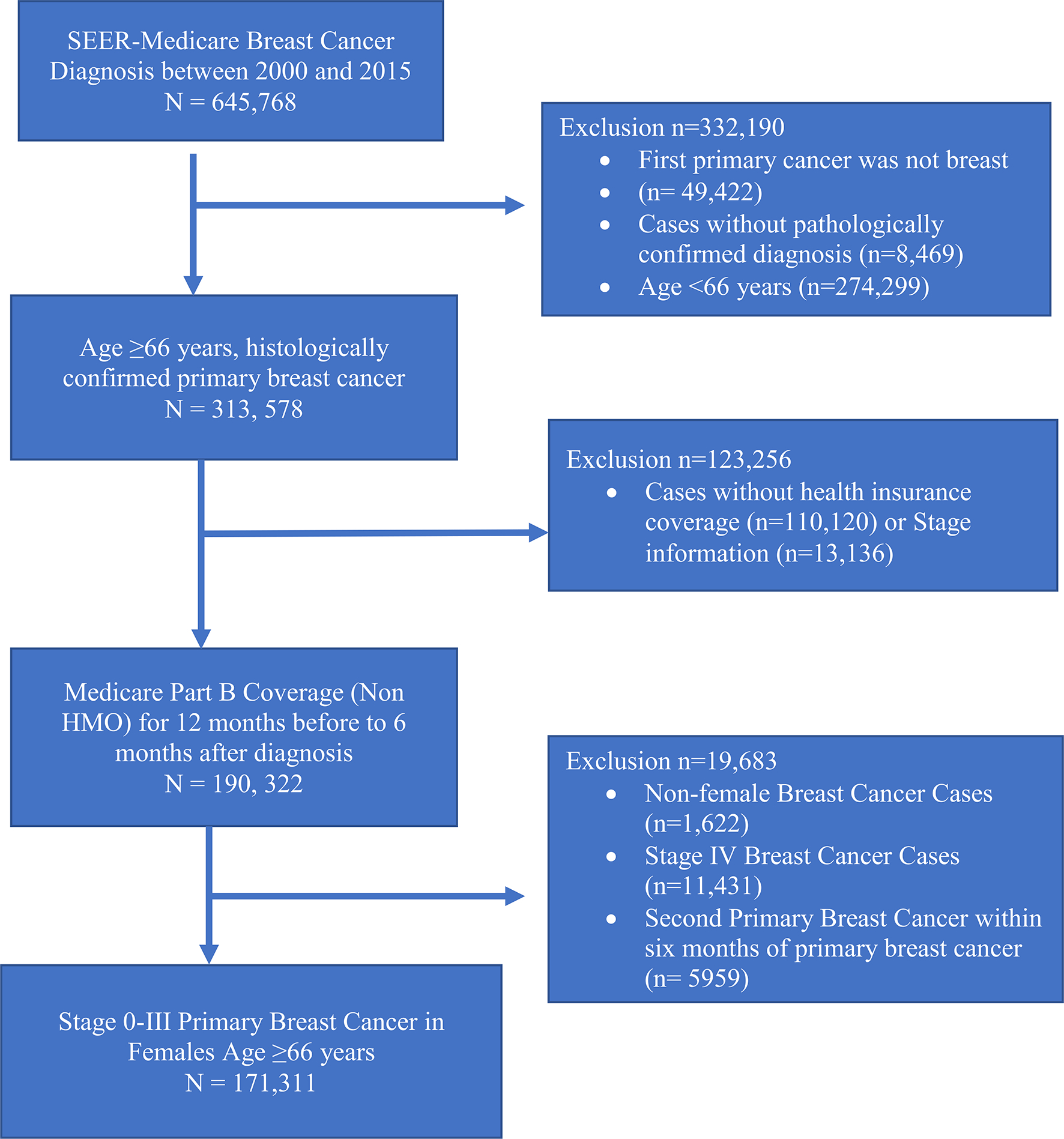

We identified patients 66 years of age and older who were diagnosed with primary BC between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2015, in the SEER-Medicare database (Fig. 1). We only included patients with a pathologically confirmed primary BC diagnosis. Those with diagnoses made at autopsy and with death certificate were excluded. We further limited our cohort to include only female patients, with early stage (0–III) primary BC.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the final cohort selection. HMO health maintenance organization; Part B = supplemental insurance

Sociodemographic variables were extracted from Medicare-linked claims and included age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, income quartile, county/residency type, marital status, first treatment regimen, comorbidities, and medications. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) comorbidity indices were calculated using the recommended 2014 comorbidity SAS Macro. Weights specific for breast cancer patients and comorbid conditions identified by hospital and physician/outpatients claims in the SEER-Medicare database were used to customize the macro. Patients were considered to have specific comorbidities if there was at least one inpatient or two outpatient Medicare claims code for the diagnosis within 1 year prior to cancer diagnosis up until 6 months after primary BC diagnosis. BC treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) was extracted using International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision (ICD-9), and Health Care Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) procedural codes. Prescription medication use was obtained from Medicare Part D files. Patients were considered to use the medications of interest (Table 2) if they had a prescription for the medication filled within the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis until 6 months after diagnosis. This study was deemed exempt by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board.

Table 2.

Medications associated with the development of second primary cancers among primary breast cancer survivors

| Medication | Second Primary Cancer Development, (N = 20, 838) | No Second Primary Cancer Development, (N = 149, 801) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Statins, N (%) | 4808 (22.3) | 29,349 (19.6) | < 0.001 |

| Antihypertensive, N (%) | 8088 (37.6) | 47,988 (32.0) | < 0.001 |

| Bisphosphonates, N (%) | 1521 (7.1) | 9300 (6.2) | < 0.001 |

| Aromatase Inhibitor, N (%) | 679 (3.2) | 10,523 (7.0) | < 0.001 |

| Metformin, N (%) | 1291 (6.0) | 7636 (5.1) | < 0.001 |

| Insulin, N (%) | 624 (2.9) | 3779 (2.5) | 0.001 |

| Thiazolidinediones, N (%) | 238 (1.1) | 1337 (0.9) | 0.002 |

| SGLT-2 Inhibitors, N (%) | 3 (0.01) | 110 (0.1) | 0.002 |

| DPP-4 Inhibitors, N (%) | 278 (1.3) | 1793 (1.2) | 0.23 |

| GLP-1 Agonists, N (%) | 38 (0.2) | 236 (0.2) | 0.51 |

Study outcome

The primary outcome was development of any SPC. We excluded diagnosis claims of BC that occurred within six months of the primary BC to remove what were likely multiple primary tumors.

Statistical analysis

We conducted chi-square tests to evaluate differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without SPCs, and to determine the association between types of medications and development of SPCs. To estimate the effects of covariates on the rate of SPC occurrence, we used a cause-specific hazard model in the presence of competing risk. The time to development of SPC was defined as the time since the initial BC diagnosis, with a delayed entry of 6 months after the primary BC diagnosis, until SPC occurrence, end of follow-up, or death. The 6 month latency period is in line with SEER Solid Tumor Rules which aims to distinguish single from multiple primary tumors. Patients who experienced death as a competing risk and those who did not develop a SPC were censored. Three cause-specific models were developed: all SPCs, breast only as a SPC, and non-breast SPCs. The results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI). In all models, Her2/neu data was excluded because it was not recorded by the SEER registry for all years evaluated in this study. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4), with the two-sided significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

Final cohort characteristics

The final cohort of primary early-stage BC survivors included 171,311 women, with a mean age at diagnosis of 75 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 6.36). SPC development occurred in 12.6% (n = 21,510) of patients. The total study population consisted of 84% non-Hispanic white, 8% non-Hispanic Black, and 4% Hispanic women. Most of the population lived in urban counties (98%) and 45% were married. The distribution of primary BC stages was: 18% stage 0, 46% stage I, 27% stage II, and 9% stage III. Sixty-eight percent of primary breast tumors were classified as ductal carcinoma. Most tumors were classified as hormone receptor (HR) positive/Her2 negative (79%), and only 9% were triple negative tumors. Surgery occurred in 94% of the population, while 17% underwent chemotherapy, and 40% underwent radiotherapy. Most of the women had an NCI Comorbidity Index score of < 1 (79%). Antihypertensives and statins were the most prescribed medications used by 33% and 20% of the cohort, respectively.

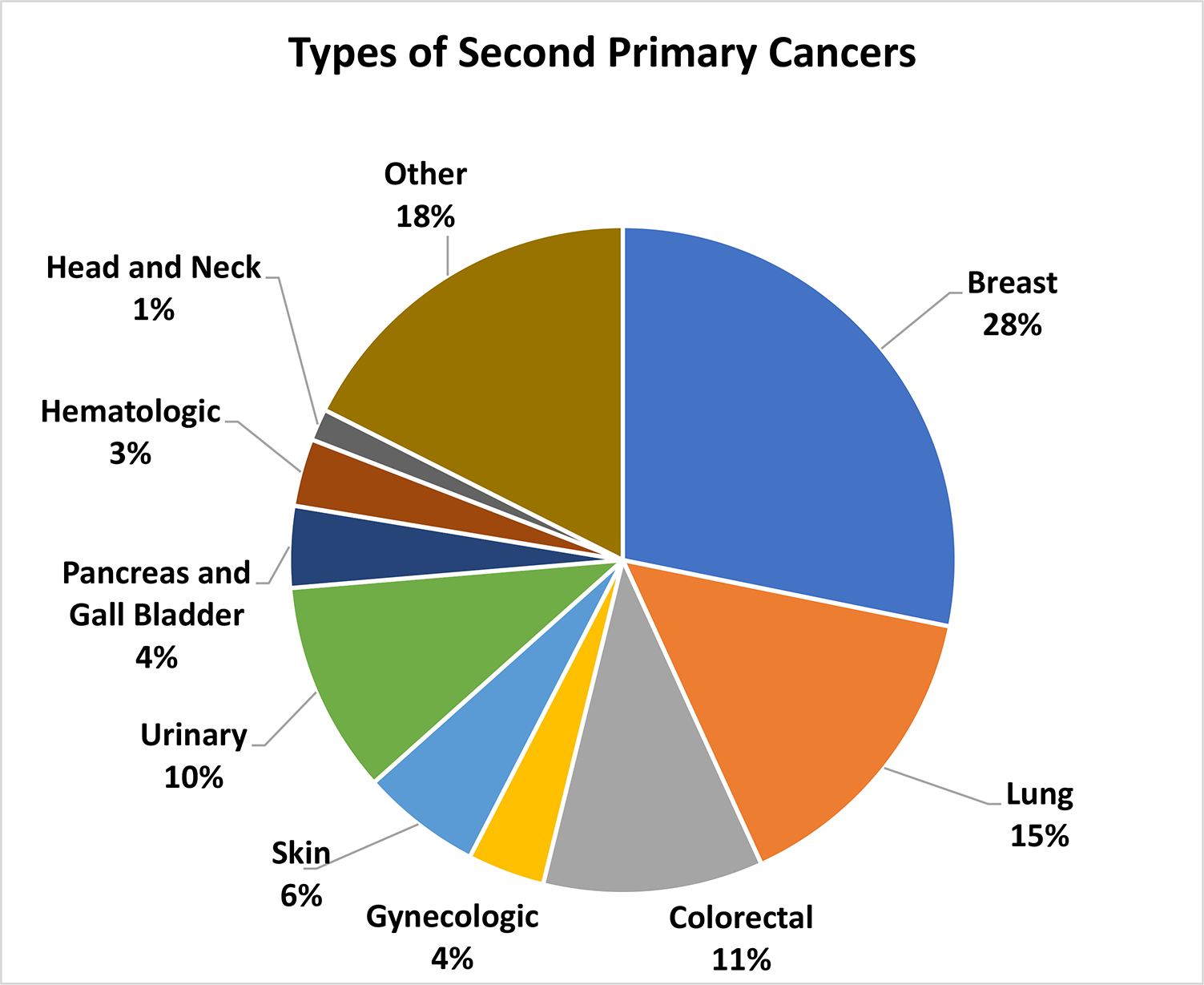

Types of second primary cancers

Of the 21,510 patients who developed a SPC, 28% had a second primary BC (Fig. 2). Lung, colorectal, and urinary cancers comprised 15%, 11%, and 10% of SPC’s, respectively. Skin and gynecologic cancers accounted for 6% and 4% of SPCs, respectively. Gallbladder/pancreatic and hematologic cancers each occurred in 4% and 3% of the patient population, respectively. Other SPCs included liver, gastrointestinal, bone and soft tissue, endocrine, and brain, which collectively accounted for 18% of the SPCs. The median time between primary BC and SPC diagnosis was 3.67 years (IQR: 5.09).

Fig. 2.

Types of second primary cancers among primary breast cancer patients. Other includes Liver, GI, Soft Tissue, Bone, Endocrine, Brain and CNS, and other

Factors associated with the development of SPCs

Unadjusted analysis (Table 1) revealed that SPC cases were more often diagnosed in white patients (12.8 vs. 12.1% among black, 11.6% among Hispanic and 10.2% among other races), those who were somewhat older (13.7% for 70–79 years vs. 12.9% for 66–69 years), and those with fewer comorbidities (12.9% NCI comorbidity index < 1 vs. 12.1% for NCI comorbidity index 1–2 and 10.2% for NCI comorbidity index > 2). Additionally, married BC survivors (12.9 vs. 12.3%) and those in the highest income quartile (12.8 vs. 12.5%) were more likely to develop SPCs. SPCs also occurred more often with stage 0 vs. stage I disease (15.4 vs. 12.8%) and those who underwent surgery (12.7 vs. 9.8%) or radiation therapy (13.5 vs. 11.9%). Chemotherapy was not significantly associated with development of SPC (p = 0.637). Additionally, patients who were prescribed medications such as statins, antihypertensives, and thiazolidinediones were more likely to develop a SPC, while those taking aromatase inhibitors were less likely to develop a SPC (p < 0.001, Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with development of second primary cancer

| Patient Characteristics (N, %) | Second primary cancer development (N, %) 21,510 (12.6) | No second primary cancer development (N, %) 149,801 (87.4) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age | |||

| 66–69 | 5147 (12.9) | 34,634 (87.1) | < 0.001 |

| 70–74 | 6225 (13.7) | 39,224 (86.5) | |

| 75–79 | 5364 (13.7) | 33,690 (86.8) | |

| > 80 | 4774 (10.2) | 42,263 (90.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 18,316 (12.8) | 124,813 (87.6) | < 0.001 |

| Black | 1595 (12.1) | 11,545 (88.2) | |

| Hispanic | 794 (11.6) | 6319 (89.2) | |

| Other | 805 (10.2) | 7124 (90.1) | |

| Geographic status | |||

| Urban | 21,091 (12.6) | 146,827 (87.8) | 0.514 |

| Rural | 385 (12.1) | 2778 (88.4) | |

| Income quartile | |||

| First quartile | 5272 (12.5) | 37,016 (88.1) | 0.390 |

| Second quartile | 5365 (12.5) | 37,515 (88.0) | |

| Third quartile | 5403 (12.6) | 37,381 (88.0) | |

| Fourth quartile | 5442 (12.8) | 36,980 (87.2) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 9841 (12.9) | 66,642 (87.3) | < 0.001 |

| Not married | 11,669 (12.3) | 83,159 (88.2) | |

| Tumor stage | |||

| Stage 0 | 4648 (15.4) | 25,601 (84.9) | < 0.001 |

| Stage I | 10,015 (12.8) | 68,494 (87.6) | |

| Stage II | 5335 (11.4) | 41,539 (89.0) | |

| Stage III | 33 (6.6) | 469 (94.0) | |

| Stage IIIA | 753 (10.4) | 6479 (90.0) | |

| Stage IIIB | 344 (8.5) | 3728 (92) | |

| Stage IIIIC | 382 (9.9) | 3491 (91.9) | |

| Tumor histology | |||

| Ductal | 14,571 (12.4) | 102,546 (87.9) | < 0.001 |

| Lobular | 1967 (11.8) | 14,723 (88.3) | |

| Other | 4972 (13.2) | 32,532 (87.1) | |

| Estrogen receptor status | |||

| ER+ | 14,675 (11.6) | 111,440 (88.6) | < 0.001 |

| ER− | 2821 (12.5) | 19,822 (88.0) | |

| Progesterone receptor status | |||

| PR+ | 12,334 (11.6) | 93,917 (88.7) | 0.009 |

| PR− | 4901 (12.1) | 35,604 (88.3) | |

| Her2 receptor status | |||

| Her2+ | 274 (4.9) | 5350 (95.1) | 0.156 |

| Her2− | 2339 (5.3) | 41,621 (94.5) | |

| Breast subtype | |||

| Her2+/HR+ | 188 (4.7) | 3775 (95.2) | 0.303 |

| Her2+/HR− | 86 (5.2) | 1561 (94.7) | |

| Her2−/HR+ | 2077 (5.3) | 37,229 (94.5) | |

| Triple negative | 260 (5.7) | 4331 (94.5) | |

| Surgery | |||

| Yes | 20,407 (12.7) | 140,397 (87.6) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1103 (9.8) | 9404 (90.2) | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 3620 (12.5) | 25,404 (87.9) | 0.637 |

| No | 17,890 (12.6) | 124,397 (87.8) | |

| Radiotherapy | |||

| Yes | 9319 (13.5) | 59,824 (86.9) | < 0.001 |

| No | 1219 (11.9) | 89,977 (88.4) | |

| NCI comorbidity index | |||

| < 1 | 17,422 (12.9) | 117,801 (87.5) | < 0.001 |

| 1–2 | 2538 (12.1) | 18,366 (88.1) | |

| > 2 | 1550 (10.2) | 13,634 (90.2) | |

In multivariable-adjusted models (Table 3), the hazard of developing any SPC was greater in patients aged 75–79 [HR 1.121 (1.078–1.165)], highest income quartile [HR 1.066 (1.025–1.108)], and with stage IIIC BC compared to stage 0 [HR 1.169 (1.051–1.300)]. Those who had a greater number of comorbidities [HR 0.735 (0.690–0.784)] had a lower hazard of developing a SPC. However, BC survivors with the following comorbidities had increased hazard of developing any SPC: diabetes [HR 1.363 (1.303–1.426)], renal disease [HR 1.405 (1.333–1.481)], and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [HR 1.760 (1.699–1.824)]. We also observed a lower hazard of SPC in patients who were taking bisphosphonates [HR 0.905 (0.857–0.956)] and aromatase inhibitors [HR 0.620 (0.573–0.671)]. Medications such as anti-hypertensives [HR 1.569 (1.512–1.627)] and statins [HR 1.066 (1.023–1.110)] increased the hazard of SPCs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional cause-specific hazard models to evaluate the effects of covariates on the rate of second primary cancer development among primary breast cancer survivors

| Patient characteristic | All SPCs HR (95% CI) | Breast Only SPCs* HR (95% CI) | Non-Breast SPCs* HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years) (REF = 66–69) | |||

| 70–74 | 1.078 (1.038–1.118)* | 0.990 (0.926–1.059) | 1.117 (1.068–1.168)* |

| 75–79 | 1.121 (1.078–1.165)* | 0.957 (0.891–1.029) | 1.187 (1.133–1.243)* |

| ≥ 80 | 1.056 (1.012–1.101)* | 0.820 (0.757–0.888)* | 1.127 (1.072–1.184)* |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | REF | REF | REF |

| Black | 0.952 (0.903–1.005) | 1.071 (0.972–1.179) | 0.907 (0.851–0.967)* |

| Hispanic | 0.832 (0.774–0.893)* | 0.821 (0.717–0.939)* | 0.819 (0.752–0.891)* |

| Other | 0.799 (0.745–0.859)* | 0.823 (0.723–0.936)* | 0.776 (0.712–0.845)* |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 0.985 (0.957–1.013) | 1.035 (0.982–1.091) | 0.969 (0.938–1.002) |

| Income quartile | |||

| First (Lowest) | REF | REF | REF |

| Second | 1.023 (0.984–1.063) | 1.036 (0.963–1.114) | 1.020 (0.975–1.067) |

| Third | 1.047 (1.007–1.088)* | 1.084 (1.008–1.167)* | 1.034 (0.988–1.082) |

| Fourth (Highest) | 1.066 (1.025–1.108)* | 1.095 (1.017–1.179)* | 1.057 (1.010–1.107)* |

| Geographic residence (REF = urban) | |||

| Rural | 0.943 (0.852–1.044) | 0.997 (0.826–1.204) | 0.921 (0.816–1.040) |

| Breast cancer stage | |||

| Stage I | REF | REF | REF |

| Stage 0 | 1.094 (1.052–1.138)* | 1.434 (1.339–1.536)* | 0.948 (0.903–0.995)* |

| Stage II | 0.999 (0.964–1.035) | 0.886 (0.825–0.952)* | 1.031 (0.989–1.073) |

| Stage III | 0.845 (0.599–1.191) | 1.156 (0.637–2.098) | 0.725 (0.476–1.103) |

| Stage IIIA | 1.009 (0.934–1.091) | 0.827 (0.699–0.979)* | 1.054 (0.966–1.151) |

| Stage IIIB | 1.076 (0.963–1.202) | 1.081 (0.864–1.353) | 1.052 (0.926–1.196) |

| Stage IIIC | 1.169 (1.051–1.300)* | 1.262 (1.029–1.549)* | 1.123 (0.992–1.271) |

| Tumor histology | |||

| Ductal | REF | REF | REF |

| Lobular | 0.972 (0.926–1.019) | 1.133 (1.037–1.237)* | 0.914 (0.864–0.968)* |

| Other | 1.023 (0.990–1.057) | 1.085 (1.022–1.153)* | 1.003 (0.964–1.043) |

| ER status (REF = ER positive) | |||

| ER negative | 1.130 (1.071–1.192)* | 1.442 (1.304–1.595)* | 1.032 (0.969–1.100) |

| PR status (REF = PR Positive) | |||

| PR negative | 0.996 (0.954–1.040) | 0.971 (0.892–1.058) | 1.006 (0.957–1.058) |

| Comorbidity index | |||

| 0.00–1.00 | REF | REF | REF |

| 1.01–2.00 | 0.780 (0.738–0.824)* | 0.701 (0.629–0.781)* | 0.779 (0.730–0.830)* |

| > 2.00 | 0.735 (0.690–0.784)* | 0.697 (0.612–0.794)* | 0.699 (0.649–0.812)* |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 1.363 (1.303–1.426)* | 1.277 (1.168–1.369)* | 1.443 (1.369–1.521)* |

| Renal disease | 1.405 (1.333–1.481)* | 1.320 (1.183–1.474)* | 1.485 (1.398–1.577)* |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.760 (1.699–1.824)* | 1.223 (1.132–1.321)* | 2.032 (1.953–2.115)* |

| Cancer treatment | |||

| Surgery | 0.743 (0.698–0.791)* | 0.714 (0.636–0.802)* | 0.753 (0.699–0.812)* |

| Radiation therapy | 1.024 (0.995–1.055) | 0.980 (0.928–1.036) | 1.053 (1.017–1.090)* |

| Chemotherapy | 1.031 (0.987–1.078) | 0.896 (0.820–0.978)* | 1.097 (1.043–1.154)* |

| Medications | |||

| Aromatase Inhibitor | 0.620 (0.573–0.671)* | 0.467 (0.393–0.554)* | 0.635 (0.581–0.694)* |

| Statins | 1.066 (1.023–1.110)* | 1.131 (1.048–1.221)* | 1.055 (1.005–1.108)* |

| Anti-hypertensives | 1.569 (1.512–1.627)* | 1.978 (1.845–2.120)* | 1.530 (1.464–1.598)* |

| Bisphosphonates | 0.905 (0.857–0.956)* | 0.898 (0.812–0.993)* | 0.892 (0.836–0.952)* |

| Metformin | 1.054 (0.986–1.127) | 1.041 (0.915–1.185) | 1.072 (0.992–1.159) |

| Insulin | 0.908 (0.898–1.071) | 1.097 (0.926–1.300) | 0.944 (0.851–1.047) |

| Thiazolidinediones | 0.816 (0.714–0.931)* | 0.651 (0.496–0.853)* | 0.870 (0.748–1.013) |

| SGLT2-inhibitors | 0.388 (0.125–1.206) | 0.000 (0.000–1.55E39)¥ | 0.470 (0.151–1.464) |

| DDP4-inhibitors | 1.057 (0.933–1.197) | 1.208 (0.955–1.529) | 1.043 (0.900–1.208) |

| GLP1-agonists | 1.289 (0.932–1.784) | 1.265 (0.690–2.320) | 1.311 (0.892–1.927) |

Insufficient number of observations

In contrast to any SPC, the hazard of developing breast-only SPC was significantly lower in Hispanic BC survivors [HR 0.821 (0.717–0.939)] and higher in those diagnosed with earlier stage BC (stage 0 vs. stage I) [HR 1.434 (1.339–1.536)]. While patients with estrogen receptor (ER) negative status had an increased hazard for BC only SPC [HR 1.442 (1.304–1.595)], patients who received chemotherapy [HR 0.896 (0.820–0.978)] and were taking bisphosphates [HR 0.898 (0.812–0.993)] as well as thiazolidinediones [HR 0.651 (0.496–0.853)] had a significantly lower hazard.

Compared to the breast only SPC group, the factors associated with greater hazard for non-breast SPC were somewhat different. The hazard for non-breast SPCs was highest for patients 75–79 years old [HR 1.187 (1.133–1.243)] compared to those 66–69 years old. Patients who underwent chemotherapy [HR 1.097 (1.043–1.151)] or radiation therapy [HR 1.053 (1.017–1.090)] for their initial primary BC had an increased risk of developing a non-breast SPC. We observed a similar trend for decreased hazard of developing a non-BC SPC in patients who were on medications such as aromatase inhibitors [HR 0.635 (0.581–0.694)] and bisphosphonates [HR 0.892 (0.836–0.952)]. An increased hazard of SPC was observed for those with comorbidities such as diabetes [HR 1.443 (1.369–1.521)], renal disease [HR 1.485 (1.398–1.577) and COPD [HR 2.032 (1.953–2.115)].

Discussion

In this study, we determined the incidence of second primary cancers (SPCs) among early-stage breast cancer (BC) survivors and identified several sociodemographic and clinical risk factors associated with the development of SPCs. Using the SEER-Medicare Linked Database with detailed information about Medicare beneficiaries with cancer from 19 geographic regions in the United States (US), we found that the incidence of any SPC among older women with primary BC was 13%. Women of white race and those who were married were more likely to develop a SPC. Additionally, hormone receptor (HR) negative primary BC diagnosed at Stage 0, treated with surgery or radiotherapy, were also associated with incidence of SPC.

While older age at BC diagnosis (ages 70–79), was associated with increased development of SPC, we observed a decline in the incidence of SPC among women ≥ 80 years after adjusting for competing risk of death which is consistent with other studies [5]. Compared to white women, the incidence of any SPC was lower for women of non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other races. The higher incidence of SPC among white women may be due to their overall higher survival rates after BC diagnosis or due to increased surveillance practices [6]. It is noteworthy that prolonged survival is an independent risk factor for the development of SPC [7]. We also observed that married women were more likely to develop a SPC. Patients who are married may be more likely to get psychosocial and financial support which may aid in early cancer detection, appropriate treatment, and prolonged survival [8].

We found that the incidence of all SPCs was higher in those with ductal primary BCs, compared to lobular, as well as in triple negative BC. After adjusting for confounders, primary BC histology was not significantly associated with SPC development, however, estrogen receptor (ER) negative cancers specifically conferred a higher risk of all SPCs. Though most studies tend to focus on combined ER/PR hormone receptor status, it has been found that most BRCA1-associated breast cancers, which are susceptible to recurrence, are ER negative [9]. In general, HR negative tumors are more likely to be poorly differentiated with increased recurrence rates [10, 11]. The increased recurrence rates may be explained by carcinogenesis research which demonstrated that BC stem cells are HR negative, and thus patients with HR negative tumors are predisposed to cancer early in the breast cell maturation process [12]. As such, patients with HR negative breast tumors have a tenfold increased risk of developing a second HR negative tumor, as compared to the general population [12].

The current treatment for BC includes surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and more recently immunotherapy. Most BC survivors in our cohort (94%) received surgery as initial treatment for their primary BC, and surgery was associated with a lower hazard of developing any SPC. This is supported by other studies which showed that patients who did not receive surgery for BC conversely had a higher risk of any SPC including breast [13–15]. We found that chemotherapy was associated with a decreased risk for breast only SPC, but increased the risk of all other SPCs, which is corroborated by studies linking certain chemotherapy drugs with different types of cancers [16, 17]. Li et al. reported that SPCs, particularly colon and lung cancers, were higher in patients who received chemotherapy for primary BC, even after adjusting for known confounders [13]. Another SEER-based study determined that chemotherapy for BC patients was associated with increased incidence for several SPCs, except for some hematologic malignancies [17]. Though the mechanism of how chemotherapy may inadvertently stimulate cancer growth remains largely unclear, it has been shown to be most linked to leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome [18, 19]. Research regarding the risks of radiation for BC are also generally inconclusive. Radiation therapy has been associated with risk for SPC in the contralateral breast or ipsilateral lung [20–22]. Other studies have shown that only 8% of SPCs are related to radiotherapy [23, 24]. Lung cancer was the second highest SPC in our cohort. This is supported by studies that report an increase in secondary malignancy of lung tissue following radiation therapy for BC [25, 26].

Finally, we observed significant associations between certain medications and the development of SPCs. Statins and anti-hypertensives were both associated with increased hazard of developing any SPC including breast SPC. A large population-based study determined that certain antihypertensives, including loop and thiazide diuretics, were associated with adverse BC outcomes, such as increased risk of breast SPCs, recurrence, and BC mortality [27, 28]. Thiazide diuretics specifically are associated with insulin resistance, which has been found to be an established risk factor for BC and may also explain the risk associated with antihypertensives [27, 29, 30]. While the biological mechanisms are unclear, statins have also been shown to impact cancer outcomes, with varying results for different cancer types. For example, a SEER-based study determined that statin use improved overall and lung cancer specific survival in patients with Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), citing in vitro studies that have demonstrated reduced proliferation, migration, and increased apoptosis of lung cancer cell lines with simvastatin use [31]. Prior studies have also explored the use of metformin in cancer treatment, as it has been shown to have a potential antitumor effect [32, 33], though it was not significantly associated with decreased risk of SPCs in our multivariable adjusted models.

Bisphosphonates and aromatase inhibitors were associated with decreased hazard of developing any SPC including non-breast SPCs. Bisphosphonates have been shown to decrease risk of both locoregional/distant BC recurrence or second primary BC [34–38]. Its effect on the development of other SPCs is less well understood. However, anti-tumor properties have been shown in preclinical studies [39] and it is effective in reducing the risk of bone metastases [34, 40–42]. Aromatase inhibitor therapy is the gold standard for the treatment of HR positive BC in post-menopausal BC survivors [43–49]. Preclinical studies have shown that aromatase inhibitors in combination with standard cisplatin chemotherapy for NSCLC decreases tumor progression [31]. Post-menopausal hormone exposure was also associated with a reduced risk for later development of NSCLC in the general population [50].

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths. It is one of the first to comprehensively explore several risk-based factors associated with development of SPCs which can provide guidance to clinicians for cancer screening and prevention among postmenopausal BC survivors. We used the SEER-Medicare database which includes clinical and demographic information about Medicare beneficiaries with cancer from 19 geographic regions in the US, representing about 28% of the population. Therefore, our results can be generalized to postmenopausal BC survivors who are at an increased risk of SPCs due to aging and comorbidities. In our adjusted analyses we also modeled all SPCs, breast only SPCs, and non-breast SPCs to isolate the effects of treatment and medications on the development of SPCs.

There are inherent limitations of this study. It is possible that certain SPCs may have been recurrence or metastases of primary BC. This was mitigated by excluding patients for whom the SPC was a BC diagnosed within six months of the primary BC diagnosis. We were unable adjust for other potential confounders, such as family history of cancer, and reproductive or lifestyle factors such as smoking or obesity. Finally, we do not have detailed treatment information such as type of chemotherapy or radiation therapy dose.

Conclusion

In summary, SPCs pose a threat to BC survivors, though the nuances in potential biologic and epidemiologic explanations remain unclear. Our comprehensive exploration uncovered several risk-based factors such as tumor stage, histology, medications, and comorbidities that can provide guidance to clinicians for cancer screening and prevention among postmenopausal BC survivors.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (T32CA225617 to SB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors Stacyann Bailey, Charlotte Ezratty, Grace Mhango, and Jenny Lin have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval This study was deemed exempt by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from NCI SEER-Medicare, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of NCI SEER-Medicare.

References

- 1.Cheng Y, Huang Z, Liao Q, Yu X, Jiang H, He Y, et al. Risk of second primary breast cancer among cancer survivors: implications for prevention and screening practice. PLoS ONE. 2020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Dong C, Chen L. The clinicopathological features of second primary cancer in patients with prior breast cancer. Medicine. 2017;96: e6675. 10.1097/MD.0000000000006675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marcu LG, Santos A, Bezak E. Risk of second primary cancer after breast cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:51–64. 10.1111/ecc.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung H, Hyun N, Leach CR, Yabroff KR, Jemal A. Association of first primary cancer with risk of subsequent primary cancer among survivors of adult-onset cancers in the United States. JAMA. 2020;324:2521. 10.1001/jama.2020.23130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li D, Weng S, Zhong C, Tang X, Zhu N, Cheng Y, et al. Risk of second primary cancers among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2020. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yedjou C, Tchounwou P, Payton M, Miele L, Fonseca D, Lowe L, et al. Assessing the racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:486. 10.3390/ijerph14050486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Wu Q, Song J, Zhang Y, Zhu S, Sun S. Risk of second primary female genital malignancies in women with breast cancer: a SEER analysis. Horm Cancer. 2018;9:197–204. 10.1007/s12672-018-0330-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin JS. The effect of marital status on stage, treatment, and survival of cancer patients. JAMA. 1987;258:3125. 10.1001/jama.1987.03400210067027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Putti TC, El-Rehim DMA, Rakha EA, Paish CE, Lee AH, Pinder SE, et al. Estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinomas: a review of morphology and immunophenotypical analysis. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:26–35. 10.1038/modpathol.3800255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahleh Z Androgen receptor as a target for the treatment of hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: an unchartered territory. Future Oncol. 2008;4:15–21. 10.2217/14796694.4.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee A, Djamgoz MBA. Triple negative breast cancer: emerging therapeutic modalities and novel combination therapies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:110–22. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurian AW, McClure LA, John EM, Horn-Ross PL, Ford JM, Clarke CA. Second primary breast cancer occurrence according to hormone receptor status. JNCI J Natl Cancer Institut. 2009;101:1058–65. 10.1093/jnci/djp181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Z, Wang K, Shi Y, Zhang X, Wen J. Incidence of second primary malignancy after breast cancer and related risk factors—Is breast-conserving surgery safe? A nested case–control study. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:352–62. 10.1002/ijc.32259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal S, Pappas L, Matsen CB, Agarwal JP. Second primary breast cancer after unilateral mastectomy alone or with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy. Cancer Med. 2020;9:8043–52. 10.1002/cam4.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi M, Cormier JN, Xing Y, Giordano SH, Chai C, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. Other primary malignancies in breast cancer patients treated with breast conserving surgery and radiation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1514–21. 10.1245/s10434-012-2774-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerr AJ, Dodwell D, McGale P, Holt F, Duane F, Mannu G, et al. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant breast cancer treatments: a systematic review of their effects on mortality. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022;105:102375. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei J-L, Jiang Y-Z, Shao Z-M. Survival and chemotherapy-related risk of second primary malignancy in breast cancer patients: a SEER-based study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:934–40. 10.1007/s10147-019-01430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel SA. Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia risk associated with solid tumor chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:303. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan HG, Malmgren JA, Atwood MK. Increased incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia following breast cancer treatment with radiation alone or combined with chemotherapy: a registry cohort analysis 1990–2005. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:260. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazonakis M, Stratakis J, Lyraraki E, Damilakis J. Risk of contralateral breast and ipsilateral lung cancer induction from forward-planned IMRT for breast carcinoma. Physica Med. 2019;60:44–9. 10.1016/j.ejmp.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y-J, Huang T-W, Lin F-H, Chung C-H, Tsao C-H, Chien W-C. Radiation therapy for invasive breast cancer increases the risk of second primary lung cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:782–90. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Curtis RE, Gilbert E, Berg CD, Smith SA, Stovall M, et al. Second solid cancers after radiotherapy for breast cancer in SEER cancer registries. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:220–6. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Gonzalez AB, Curtis RE, Kry SF, Gilbert E, Lamart S, Berg CD, et al. Proportion of second cancers attributable to radiotherapy treatment in adults: a cohort study in the US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:353–60. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yadav BS, Sharma SC, Patel FD, Ghoshal S, Kapoor RK. Second primary in the contralateral breast after treatment of breast cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2008;86:171–6. 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zablotska LB, Neugut AI. Lung carcinoma after radiation therapy in women treated with lumpectomy or mastectomy for primary breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1404–11. 10.1002/cncr.11214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neugut AI, Lee WC, Murray T, Robinson E, Karwoski K, Kutcher GJ. Lung cancer after radiation therapy for breast cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:3054–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L, Chubak J, Boudreau DM, Barlow WE, Weiss NS, Li CI. Use of antihypertensive medications and risk of adverse breast cancer outcomes in a SEER–medicare population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26:1603–10. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phadke S, Clamon G. Beta blockade as adjunctive breast cancer therapy: a review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;138:173–7. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du R, Lin L, Cheng D, Xu Y, Xu M, Chen Y, et al. Thiazolidinedione therapy and breast cancer risk in diabetic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34: e2961. 10.1002/dmrr.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biello F, Platini F, D’Avanzo F, Cattrini C, Mennitto A, Genestroni S, et al. Insulin/IGF axis in breast cancer: clinical evidence and translational insights. Biomolecules. 2021;11:125. 10.3390/biom11010125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin JJ, Ezer N, Sigel K, Mhango G, Wisnivesky JP. The effect of statins on survival in patients with stage IV lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2016;99:137–42. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vancura A, Bu P, Bhagwat M, Zeng J, Vancurova I. Metformin as an anticancer agent. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2018;39:867–78. 10.1016/j.tips.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin JJ, Gallagher EJ, Sigel K, Mhango G, Galsky MD, Smith CB, et al. Survival of patients with stage IV lung cancer with diabetes treated with metformin. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:448–54. 10.1164/rccm.201407-1395OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korde LA, Doody DR, Hsu L, Porter PL, Malone KE. Bisphosphonate use and risk of recurrence, second primary breast cancer, and breast cancer mortality in a population-based cohort of breast cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2018;27:165–73. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brufsky A Adjuvant bisphosphonates for early-stage breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:610–1. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathew A, Brufsky A. Decreased risk of breast cancer associated with oral bisphosphonate therapy. Breast Cancer. 2012. 10.2147/BCTT.S16356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holen I, Coleman RE. Anti-tumour activity of bisphosphonates in preclinical models of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:214. 10.1186/bcr2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathew A, Brufsky A. Bisphosphonates in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:753–64. 10.1002/ijc.28965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Croucher P, Jagdev S, Coleman R. The anti-tumor potential of zoledronic acid. The Breast. 2003;12:S30–6. 10.1016/S0960-9776(03)80161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Carrigan B, Wong MH, Willson ML, Stockler MR, Pavlakis N, Goodwin A. Bisphosphonates and other bone agents for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;10:CD003474. 10.1002/14651858.CD003474.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Pluijm G, Vloedgraven H, van Beek E, van der Wee-Pals L, Löwik C, Papapoulos S. Bisphosphonates inhibit the adhesion of breast cancer cells to bone matrices in vitro. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:698–705. 10.1172/JCI118841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daubine F, le Gall C, Gasser J, Green J, Clezardin P. Antitumor effects of clinical dosing regimens of bisphosphonates in experimental breast cancer bone metastasis. JNCI J Natl Cancer Institut. 2007;99:322–30. 10.1093/jnci/djk054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osborne CK, Schiff R. Aromatase inhibitors: future directions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;95:183–7. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carpenter R, Miller WR. Role of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:S1–5. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sood A, Lang DK, Kaur R, Saini B, Arora S. Relevance of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer treatment. Curr Top Med Chem. 2021;21:1319–36. 10.2174/1568026621666210701143445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kharb R, Haider K, Neha K, Yar MS. Aromatase inhibitors: role in postmenopausal breast cancer. Arch Pharm (Weinheim). 2020;353:2000081. 10.1002/ardp.202000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ratre P, Mishra K, Dubey A, Vyas A, Jain A, Thareja S. Aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer: a journey from the scratch. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2020;20:1994–2004. 10.2174/1871520620666200627204105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. The Lancet 2015;386:1341–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Puntoni M, Guglielmini P, Amoroso D, Fini A, et al. Switching to anastrozole versus continued tamoxifen treatment of early breast cancer: preliminary results of the Italian tamoxifen anastrozole trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5138–47. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz AG, Wenzlaff AS, Prysak GM, Murphy V, Cote ML, Brooks SC, et al. Reproductive factors, hormone use, estrogen receptor expression and risk of non–small-cell lung cancer in women. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5785–92. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from NCI SEER-Medicare, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of NCI SEER-Medicare.