Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) and ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) are two frequent complications of critical illness which, until recently, have been considered unrelated processes. The adverse impact of AKI on ICU mortality is clear, but its relationship with muscle weakness – a major source of ICU morbidity – has not been fully elucidated. Furthermore, improving ICU survival rates have refocused the field of intensive care towards improving long-term functional outcomes of ICU survivors. We begin our review with the epidemiology of AKI in the ICU and of ICU-AW, highlighting emerging data suggesting that AKI and AKI-requiring kidney replacement therapy (AKI-KRT) may independently contribute to the development of ICU-AW. We then delve into human and animal data exploring the pathophysiologic mechanisms linking AKI and acute KRT to muscle wasting, including altered amino acid and protein metabolism, inflammatory signaling, and deleterious removal of micronutrients by KRT. We next discuss the currently available interventions that may mitigate the risk of ICU-AW in patients with AKI and AKI-KRT. We conclude that additional studies are needed to better characterize the epidemiologic and pathophysiologic relationship between AKI, AKI-KRT, and ICU-AW and to prospectively test interventions to improve the long-term functional status and quality of life of AKI survivors.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, acute renal failure, critical illness myopathy, ICU-acquired weakness, continuous kidney replacement therapy, continuous renal replacement therapy, post-intensive care syndrome, AKI, CRRT, PICS

Introduction

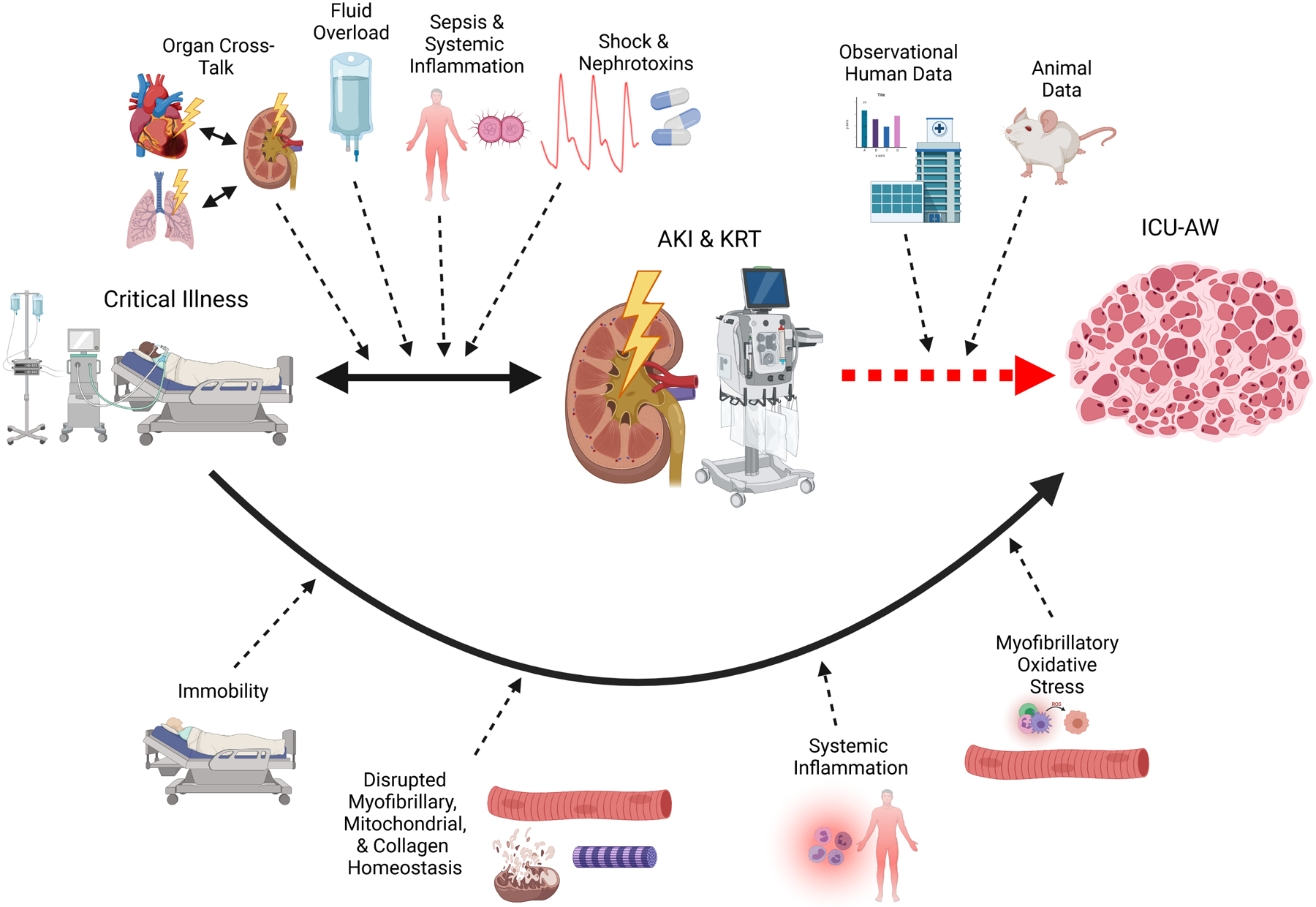

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication of critical illness, and up to 15% of patients with AKI in the intensive care unit (ICU) require kidney replacement therapy (KRT).1 Though further studies are needed, AKI and the need for acute KRT may contribute to skeletal muscle dysfunction through multiple mechanisms. The purpose of this article is to review the proposed pathophysiology of skeletal muscle loss and dysfunction in critical illness with a focus on patients with AKI requiring KRT (AKI-KRT). We describe pre-clinical and clinical data suggesting that AKI and AKI-KRT may independently contribute to ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) (Figure 1), suggest interventions that may mitigate or prevent ICU-AW in AKI patients, and identify areas of uncertainty in need of future research. Despite many unanswered questions, we propose that nephrologists should recognize AKI as risk factor for long-term functional impairment after critical illness and learn to routinely consider referring AKI survivors to physical rehabilitation.

Figure 1:

Framework for the relationship between critical illness, AKI requiring KRT, and ICU-associated weakness

AKI frequently complicates critical illness. In addition to the traditional mechanisms of AKI in critical illness such as ischemia, sepsis, and nephrotoxin exposure, AKI and critical illness have a bidirectional relationship mediated by systemic inflammation, organ cross-talk, and fluid overload, combining to produce the high rates of morbidity and mortality characteristic of AKI in the ICU. Muscle wasting is a well-known complication of critical illness mediated by immobility; systemic inflammation; altered myofibrillary, mitochondrial, and collagen protein homeostasis; and myofibrillary oxidative stress. Though not considered a traditional risk factor for ICU-AW, emerging data, both observational human studies and experimental animal data, strongly imply that AKI and KRT may directly contribute to the development of ICU-AW. Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; ICU, intensive care unit; ICU-AW, ICU-associated weakness; KRT, kidney replacement therapy. Created with BioRender.com.

AKI in the ICU: incidence and outcomes

In contemporary international cohorts, the incidence of AKI ranges from 20% to >50% of all ICU admissions, with 5–15% of critically ill patients developing AKI-KRT.2,3 Moreover, the rates of AKI, AKI-KRT, and AKI-related mortality have increased substantially in the last 20 years.4,5 Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has further increased KRT use in the ICU. AKI complicates 25–40% of all COVID-19 admissions and AKI-KRT develops in 20–45% of critically ill COVID-19 patients.6 AKI, especially AKI-KRT, carries a high short-term mortality of ≥50% across diverse ICU populations with or without COVID-19.1,4,6–10 Furthermore, observational studies have increasingly linked AKI to long-term impairments in functional status, including limited mobility, worsened quality of life (QoL), and muscle weakness.11–13

Despite chronic kidney disease (CKD) being a recognized risk factor for AKI, the relationship between AKI-on-CKD and outcomes of critical illness appears to be complex, with data suggesting mortality rates are higher in AKI-on-CKD patients than in patients with neither AKI nor CKD but lower than in patients with AKI in the setting of normal baseline kidney function.14,15 The interplay between AKI-on-CKD and long-term functional outcomes remains unknown.

ICU-acquired weakness: definition, incidence, outcomes, and risk factors

ICU-AW is defined as muscle weakness and wasting (atrophy) resulting from critical illness.16 The reported incidence of ICU-AW ranges from 40% in systematic reviews17 to >80% in individual studies.18 Muscle wasting occurs early and rapidly during critical illness.19 We and others have reported that 3–5% of baseline rectus femoris muscle size is lost in the first day of ICU admission, with up to 30% lost in the first 10 days.20–23 Importantly, ICU-AW may persist for years and is associated with mortality, hospital readmission, long-term functional impairment, and lower QoL.24–26 Traditional risk factors (Figure 2) for ICU-AW include preexisting comorbidity, high illness severity, sepsis, acute respiratory failure, prolonged immobilization, hyperglycemia, advanced age, and prolonged exposure to corticosteroids, sedatives, or paralytics.25,26

Figure 2:

Risk factors for and management of ICU-associated weakness

In addition to emerging data linking AKI and KRT to ICU-AW, risk factors for ICU-AW include prolonged immobilization, need for mechanical ventilation, use of certain medications (especially prolonged treatment with corticosteroids, sedatives, or paralytic agents), sepsis and other forms of systemic inflammation, multiorgan dysfunction, and high severity of illness. Though additional data are needed to better delineate and validate interventions to prevent and treat ICU-AW, early physical therapy and adequate nutritional support are felt to be the cornerstones of prevention and management.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; ICU, intensive care unit; ICU-AW, ICU-associated weakness; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; MOF, multiorgan failure. Created with BioRender.com.

Recent data suggest that ICU patients with AKI and AKI-KRT may also be at increased risk of ICU-AW. Specifically, a recent prospective multicenter cohort study of 642 intubated patients identified days on KRT as an independent risk factor for ICU-AW.27 Likewise, our group analyzed a cohort of 104 ICU survivors and found that patients with stage 2 or 3 AKI had increased severity of muscle weakness, lower health-related QoL, and impaired ability to return to work or driving.13 However, additional data are needed to further investigate the link between AKI, KRT, potential confounding factors such as ICU length of stay (LOS) and overall illness severity, and the risk of ICU-AW.

ICU-AW: diagnosis

For this review, in concert with prior guidelines,28 we will use the term ICU-AW as a framework that encompasses muscle atrophy, weakness, and dysfunction in ICU patients. Muscle dysfunction (ie. impaired muscle performance) due to critical illness typically results from overlapping effects of myopathy and neuropathy; however, as outlined below, the studies linking AKI and ICU-AW are overwhelmingly centered on muscle rather than nerve function. Assessment of skeletal muscle in the ICU is influenced by a patient’s ability to engage and follow simple commands and the time course and severity of their illness. With the emerging data linking AKI to ICU-AW, nephrologists practicing in the ICU should have foundational knowledge of the diagnosis and measures of ICU-AW to be able to interpret results and communicate effectively with intensivists, interprofessional team members, patients, and their care partners as part of patient-centered care (Table 1).

Table 1:

Clinical and research tests to diagnose ICU-AW or assess skeletal muscle in the ICU

| Test or Modality | Description | Limitations | Provider | Setting or Timeframe | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Research Council-sum score (MRC-ss)28 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Handgrip dynamometry (HGD)29 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Handheld dynamometry (HHD)110 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Muscle Ultrasound (US)20–23,30 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Computed Tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)30 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Electromyograp hy (EMG) and Evoked Forces111 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Muscle biopsy28 |

|

|

|

|

|

Physiatrists are physicians specializing in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation.

Patient milestones include any change in medical or functional status that requires re-evaluation (i.e., clinical decompensation or fall); ICU and hospital discharge; and 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after discharge.

Trained sonographer may be from any professional discipline that has received ultrasound-specific training; no current standard for muscle ultrasonography certification exists.

Additional abbreviations: EI, echo intensity (a surrogate marker of muscle quality); L3, level of third lumbar vertebra.

ICU-AW is diagnosed by assessing global muscle strength testing using the Medical Research Council-Sum Score (MRC-ss) in the appropriate clinical setting.26,28 MRC-ss grades volitional strength in twelve predefined peripheral muscle groups (bilateral shoulder abductors, elbow flexors, wrist extensors, hip flexors, knee extensors, and foot dorsiflexors). Handgrip dynamometry measures grip strength and has been proposed as a valid and reliable screening tool for ICU-AW, but, like MRC-ss, requires patient participation.29

Imaging permits muscle assessment in patients that are unable to follow commands, potentially leading to earlier detection of ICU-AW. Commuted tomography (CT) can quantify muscle size and quality but is rarely performed clinically for this purpose. Muscle ultrasound has similarly been proposed as a diagnostic tool to assess muscle size and quality, and has been demonstrated in ICU patients to correlate well with CT-derived measures30 and immunohistochemical analysis of muscle biopsy specimens.22,23 However, whether ultrasound reliably predicts patient-relevant outcomes including ICU-AW requires further study. Electromyography (EMG), nerve conduction velocity studies (NCV), and muscle biopsy may be useful to diagnose ICU-AW but are relatively costly and invasive techniques typically reserved for complex neuromuscular disorders and research. Ultimately, imaging, EMG/NCV, and muscle biopsy are diagnostic adjuncts to strength testing by trained providers using MRC-ss; despite its limitations, strength testing remains the gold standard and most practical method to diagnose ICU-AW.

ICU-AW: pathophysiology

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed for ICU-AW (Figure 1). Critical illness is associated with a significant inflammatory response, which has been demonstrated in experimental studies to alter mitochondrial, myofibrillar, and collagen protein homeostasis and to trigger myofibrillary oxidative stress.19 Additional animal, space flight, and human research has shown that disuse or immobility lead to muscle atrophy through mechanical silencing—the process of inducing myosin loss and atrophy through the removal or reduction of internal (i.e., muscle contraction) or external (i.e., loading or weight-bearing) stimuli.31 Patients requiring mechanical ventilation with deep sedation are therefore at the greatest risk of muscle dysfunction. We propose that AKI and acute KRT may independently contribute to ICU-AW.

Proposed mechanisms of muscle wasting in AKI

Though muscle wasting in CKD, including in kidney failure, has been studied for decades,32,33 less is known about muscle wasting in AKI. Some of the mechanisms underlying muscle wasting in CKD may apply to AKI, including systemic inflammation, metabolic acidosis, defective insulin signaling, and malnutrition stimulating mediators of muscle protein catabolism including the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), caspase-3, lysosomes, and myostatin.34 However, unrelated mechanisms may contribute to muscle wasting in AKI, as AKI and CKD are distinct clinical processes, with AKI having drastically worse prognosis in the ICU.8,14,15

The experimental data linking AKI to muscle wasting are summarized in Figure 3 and outlined in detail in Table 2. Collectively, animal studies suggest that AKI of multiple etiologies causes muscle wasting by rapid activation of protein degradation via UPS, subsequently followed by impaired protein synthesis via, in part, downregulation or disruption of activation/phosphorylation of the protein kinase mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) by the kinase Akt. The Akt-mTOR signaling pathway has been shown in other settings to promote muscle synthesis and inhibit muscle degradation in response to stimuli such as insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1.35 These studies also implicate roles for dysregulated autophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammatory mediators, especially interleukin-6 (IL-6).

Figure 3:

Potential mechanisms of muscle atrophy in critically ill patients with AKI and AKI requiring KRT

Experimental data have demonstrated that AKI within 24h causes muscle wasting by rapid activation of protein degradation via the UPS. This is followed as soon as 48h after AKI onset by impaired protein synthesis which is mediated in part by downregulation of the Akt-mTOR kinase pathway that normally functions to promote muscle anabolism in response to physiologic stimuli such as leucine. Abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin response have also been demonstrated in AKI, with AKI appearing to impair the normal ability of insulin to stimulate muscle anabolism, glucose utilization, and glycogen synthesis. AKI itself induces an intense systemic inflammatory response that has been shown to cause tissue damage, inflammation, and dysfunction of multiple distant organs including the heart, and a similar effect on skeletal muscle as has been demonstrated in cardiac muscle may partly mediate AKI-induced muscle wasting. IL-6 in particular may be a central mediator of this effect, as this cytokine has been shown to play a prominent role in the systemic inflammation and organ cross-talk that follows AKI, to mediate muscle wasting in many other clinical settings, and to be upregulated in muscle tissue after AKI. Likewise, AKI and ICU-AW may be linked by oxidative stress as AKI has been shown in animal studies to induce oxidative stress of distant organs, including the heart, and oxidative stress has been associated with skeletal muscle wasting and dysfunction in multiple non-AKI models of ICU-AW. Animal data also implicate possible roles for abnormalities in mitochondrial number and function and dysregulated autophagy. In addition to stimulating inflammation, KRT (especially CKRT) may directly contribute to ICU-AW via the non-selective clearance and the resulting depletion of muscle stores of amino acids, peptides, and small proteins as well as phosphate and other metabolites.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; CKRT, continuous kidney replacement therapy; ICU-AW, ICU-associated weakness; IL-6, interleukin-6; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; UPS, ubiquitin-proteasome system. Created with BioRender.com.

Table 2:

Studies in animal models investigating the mechanisms of muscle wasting in AKI.

| Author(s), Year | AKI Model and Timing | Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitch, 1981; Clark & Mitch, 1983; May et al., 1985112–114 | Rat, 24–48h after bilateral ureteral ligation |

|

|

| Flugel-Link et al., 1983115 | Rat, 30h after bilateral nephrectomy |

|

|

| Baliga & Shah, 1991116 | Rat, gentamicin-induced AKI, assessed on day 8 after 7d of gentamicin exposure |

|

|

| Price et al., 1998117 | Rat, 40h after bilateral ureteral ligation |

|

|

| Andres-Hernando et al. 201436 | Mice, 7d after bilateral IRI (22 min of renal pedicle clamping) |

|

|

| McIntire et al., 201461 | Rat, 44h after bilateral ureteral ligation |

|

|

| Aniort et al., 201662 | Rat, gentamicin-induced AKI, assessed at day 7 after 7d of gentamicin exposure |

|

|

| Nagata et al., 202063 | Mice, 7 days after IRI [15 min of renal pedicle clamping in contralateral nephrectomized rats (AKI + uremia) or 35 min of clamping in rats with intact contralateral kidney (AKI without uremia)] |

|

|

Note that atrogin-1 is also known as muscle atrophy F-box (MAFbx). Abbreviations: AA, amino acid; AKI, acute kidney injury; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; BCAA, branched chain amino acid; BCKAD, branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase; IL-6, interleukin-6; IRI, ischemia-reperfusion injury; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; MuRF, muscle RING-finger protein; UPS, ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The ability of AKI to induce systemic inflammation and predispose to skeletal muscle wasting may be considered a form of organ “cross-talk.” Notably, such kidney-skeletal muscle cross-talk has been proposed to mediate muscle wasting in CKD.33 AKI is increasingly recognized as a systemic inflammatory state associated with multiorgan dysfunction induced by TNF-alpha, interleukin-1, IL-6, and other mediators.7,36–38 These systemic effects are hypothesized to mediate the high mortality of critically ill patients with AKI and the worse outcomes of ICU patients with AKI-KRT versus ESKD.1,7 Specifically, renal ischemia-reperfusion injury has been shown in animal models to induce cardiac oxidative stress, amino acid (AA) depletion, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and systolic and diastolic dysfunction.37,38 Similar effects of AKI on skeletal muscle may occur. IL-6 specifically has been shown in other animal models to induce or augment muscle catabolism,39 thereby providing another plausible mechanistic link between AKI and muscle breakdown. However, data to support the theory that direct inflammatory cross-talk between kidney and skeletal muscle mediates AKI-induced muscle wasting remain limited.

Proposed mechanisms of muscle wasting in acute KRT

While AKI itself may promote ICU-AW, AKI-KRT may compound muscle dysfunction by additional mechanisms (Figure 3).

The effects of KRT on muscle have been extensively studied in kidney failure, but far less is known about the impact of AKI-KRT on muscle. A recent systematic review on the acute effects of hemodialysis on skeletal muscle included 14 studies of patients with kidney failure and reported variable effects on muscle perfusion and function but consistently found that hemodialysis causes acute muscle protein breakdown and net protein loss, induces markers of muscle protein breakdown (caspase-3 activity and polyubiquitin), and triggers inflammation, especially IL-6.40

Hemodialysis and hemofiltration remove unbound water-soluble molecules non-selectively. Therefore, the effects of KRT on muscle may be mediated by non-selective removal of AAs, peptides, or small proteins. Studies decades ago demonstrated substantial removal of AAs by intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) in the setting of kidney failure.41,42 Similar significant dialytic losses of AAs, peptides, and small proteins have subsequently been demonstrated in AKI-KRT (Table 3).43–56 The loss is most pronounced in continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT), followed by prolonged intermittent KRT, and lastly by IHD,54 paralleling the cumulative clearance (i.e., standardized Kt/Vurea) typically provided by each modality. While KRT clearly removes AAs, how significantly this contributes to negative protein or nitrogen balance is unclear.50,55 For example, a recent study of ICU patients with AKI, including 31 CKRT patients and 24 non-KRT patients, measured serum AA levels at days 1 and 6.55 Effluent levels of AAs were also measured in the CKRT group and all AAs were detected.55 However, significant depletion of serum AA levels was noted before CKRT initiation and glutamic acid was the only AA with significantly lower levels in CKRT patients than in non-KRT AKI patients.55 The authors concluded that these findings refute the hypothesis that losses during KRT are the main reason for altered micronutrient profile in AKI patients.55 However, serum levels of substances do not necessarily reflect total body levels. An alternative hypothesis is that, while AKI alone does indeed result in significant disruption in AA metabolism, the added non-selective clearance of AAs by KRT may aggravate catabolism and total body depletion of AAs as serum levels are maintained at the expense of muscle breakdown.

Table 3:

Studies in humans with AKI requiring KRT demonstrating depletion of amino acids, peptides, proteins, and/or other nutrients.

| Authors, Year | N | Nutrition and other patient characteristics | KRT modality and approximate dose | Key Study Features and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davenport & Roberts, 198943 | 8 | On TPN and mechanical ventilation | High-flux CVVH (1 L/h) |

|

| Davies et al., 199144 | 8 | 6/8 on TPN | CAVHDF (Qd 1–2 L/h; variable UF) |

|

| Frankenfield et al., 199345 | 17 (+ 15 controls not on KRT) | Trauma with SIRS on TPN | CAVHDF or CVVHDF (Qd 15 or 30 mL/min; variable Qr) |

|

| Mokrzycki & Kaplan, 199646 | 7 patients (22 effluent samples) | 12 samples during TPN infusion; 1 during enteral feeding | CVVH and CVVHDF |

|

| Kihara et al., 199747 | 6 | On TPN receiving 40 g/day of AAs | PIKRT (slow HD with Qd 20 mL/min for 10h daily) |

|

| Novak et al. 199748 | 6 (+ 16 healthy controls) | On TPN; 4 with multiorgan failure; 2 with isolated AKI | CVVHDF (Qd 1 L/h) |

|

| Scheinkestel et al., 200349 | 11 | Anuric; on TPN and mechanical ventilation | CVVHD (with Qd 2L/h) |

|

| Chua et al., 201250 | 7 | 4/7 on enteral nutrition; 0/7 on TPN | PIKRT (EDHDF, 8h/day with Qb 100 mL/min, Qr 21 mL/min, and Qd 280 mL/min) |

|

| Schmidt et al., 201451 | 10 KRT sessions in 5 patients | 3/5 on TPN | PIKRT (extended dialysis, 10h per treatment with Qb and Qd of 150 mL/min) |

|

| Umber et al., 201452 | 5 | 2/5 on IV nutrition | PIKRT (12h SLED sessions with low-flux dialyzer and Qb 200 mL/min and Qd 100 mL/min) |

|

| Stapel et al., 201953 | 10 | 8 on enteral nutrition, 1 on parenteral nutrition | CVVH (high-flux membrane, Qb 180 mL/min, predilution Qr 2.4 L/h) |

|

| Oh et al., 201954 | 60 | Mix of ward and ICU patients; majority malnourished but nutritional input not recorded | 27 on IHD (2–3h, Qb 200–250 mL/min; Qd 400–500 mL/min); 12 on PIKRT (SLEDf, 6–8h daily, Qb 200 mL/min, effluent 200 mL/min); 21 on CVVH (35 mL/min) |

|

| Griffin et al., 202056 | 13 (11 AKI, 2 ESKD) | 7/13 post-cardiac surgery; nutritional input not recorded | CVVHD (25 mL/kg/h) |

|

| Ostermann et al., 202055 | 55 AKI patients (31 treated with CKRT) | On full-dose enteral nutrition (TPN excluded) | CKRT (mean total effluent dose of 46L in first 24h) |

|

Abbreviations: AA, amino acid; AKI, acute kidney injury; CAVH, continuous arterio-venous hemofiltration; CAVHDF, continuous arterio-venous hemodiafiltration; CKRT, continuous kidney replacement therapy; CVVH, continuous veno-venous hemofiltration; CVVHD, continuous veno-venous hemodialysis; CVVHDF, continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration; EDHDF, extended daily hemodiafiltration; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HD, hemodialysis; IHD, intermittent hemodialysis; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; PIKRT, prolonged intermittent kidney replacement therapy; Qb, blood flow rate; Qd, dialysate flow rate; Qr, replacement fluid rate; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SLED, sustained low-efficiency dialysis; SLEDf, sustained low-efficiency diafiltration; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; UF, ultrafiltration.

Similarly, we carried out an analysis of serum and effluent levels of 101 metabolites, including AAs, in 13 CKRT patients and, despite detecting AAs in the effluent with most dialyzer sieving coefficients approaching 1, we found reductions in serum levels of only 3 of 20 AAs.56 Notably, the reductions were seen at 24h relative to baseline, but thereafter no further reduction in AA levels was seen at 48h or 72h,56 again suggesting that serum AA levels may be maintained despite ongoing removal by CKRT at the expense of total body/muscle stores. In addition to AAs, KRT removes other nutrients, minerals, and metabolites that could potentially affect muscle function.54–56 Of these, the most studied is phosphate (Table 4). Though readily cleared from the vascular compartment by hemodialysis or hemofiltration, the kinetics of phosphate removal by IHD and CKRT differ dramatically. Because phosphate is primarily intracellular and slowly re-equilibrates with the extracellular compartment, IHD clears a relatively small amount of total-body phosphate with each treatment. CKRT, by virtue of being continuous, overcomes the slow re-equilibration between the intra- and extracellular compartments.57 CKRT ultimately removes phosphate so effectively that after 2–4 days, hypophosphatemia requiring repletion is a near-universal complication when using traditional phosphate-free CKRT solutions.57

Table 4:

Studies of hypophosphatemia induced by KRT and clinical outcomes

| Authors, Year | N | Patient characteristics and KRT modality | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demirjian et al., 201166 | 321 | AKI treated with CVVHD for >2 days |

|

| Yang et al., 201369 | 760 | AKI treated with CVVH |

|

| Bellomo et al., 201470 | 1441 | CVVHDF, with either 25 or 40 mL/kg/h of total effluent dose, with ratio of Qd and post-filter Qr of 1:1 |

|

| Sharma et al., 201558 | 20 CKRT patients (+10 controls) | 19/20 CKRT patients on mechanical ventilation; 4 CKRT patients on parenteral nutrition, 10 on enteral nutrition; controls were surgical patients mostly without AKI |

|

| Lim et al., 201760 | 96 acute KRT patients | 64 (67%) on mechanical ventilation; 44 patients received CKRT only, 28 IHD only, and 24 both |

|

| Hendrix et al., 202068 | 72 | 60 with AKI; 12 with ESKD; all treated with ≥12h of CKRT |

|

| Sharma et al., 202065 | 907 | Subset of patients in ATN trial on mechanical ventilation, with 80% starting KRT with CVVHDF, 15% with IHD, and 4.5% with SLED |

|

| Thompson-Bastin et al., 202178 | 1396 CKRT patients | 511 treated with CKRT using phosphate-free solutions; 885 treated with CKRT with phosphate-containing solutions |

|

| Thompson-Bastin et al., 202267 | 992 CKRT patients | All intubated; 343 treated with only phosphate-free CKRT solutions; 649 only with phosphate-containing solutions |

|

Abbreviations: 2,3-DPG, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate; AKI, acute kidney injury; CKRT, continuous kidney replacement therapy; CVVH, continuous veno-venous hemofiltration; CVVHD, continuous veno-venous hemodialysis; CVVHDF, continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; ICU, intensive care unit; IHD, intermittent hemodialysis; KRT, kidney replacement therapy; LOS, length of stay; OR, odds ratio; Qd, dialysate flow rate; Qr, replacement fluid rate; RBC, red blood cell; SLED, sustained low-efficiency dialysis; TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

Phosphate depletion may lead to significant and long-term effects on muscle function. For example, phosphate depletion during CKRT has been linked with decreased erythrocyte levels of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate,58 which, especially if coupled with hypophosphatemia-induced cardiovascular dysfunction,59,60 could lead to impairment in oxygen delivery to skeletal muscle. Furthermore, phosphate depletion also could directly impair the function of kinases in the Akt-mTOR pathway and other signaling pathways responsible for stimulating muscle protein synthesis.35,61–63

Data linking hypophosphatemia directly to muscle weakness in general ICU populations are limited.64 However, multiple observational studies have found hypophosphatemia to be associated with worse outcomes in CKRT patients and suggest that it may contribute to respiratory muscle dysfunction. Specifically, CKRT-induced hypophosphatemia has been independently associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation or increased need for tracheostomy, and, to a lesser degree, with increased LOS, with variable but generally neutral effects on mortality.60,65–70

As opposed to the situation with phosphate, most standard CKRT solutions contain physiologic or near-physiologic concentrations of potassium, calcium, and magnesium. As such, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, and hypomagnesemia – though present in a substantial minority of CKRT patients – develop less frequently than hypophosphatemia9,10 and fewer data exist on the impact of depletion of these electrolytes on outcomes. CKRT specifically using regional citrate anticoagulation can cause hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia,71 as citrate chelates magnesium and calcium, and both hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia have been associated with respiratory muscle weakness in small studies.72,73 Furthermore, limited data have associated hypomagnesemia and hypocalcemia with increased ICU mortality and morbidity, including respiratory failure and/or need for mechanical ventilation,74–76 potentially implicating respiratory muscle dysfunction. In contrast, hypokalemia developing during CKRT was not associated with mortality in a recent single-center study of >1200 patients.77 The relative impacts of CKRT-induced hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, or hypomagnesemia on ICU-AW remain unclear.

Interventions to mitigate micronutrient loss during KRT

Use of AA-containing dialysate has been studied in kidney failure, though the impact on outcomes and clinical uptake have been limited.41,42 There are no studies of AA-containing CKRT solutions for AKI-KRT. Studies of AA supplementation in CKRT have been performed but with limited impact on outcomes apart from maintenance of serum AA levels.49

Based on the available data, prevention of hypophosphatemia is a reasonable intervention to mitigate ICU-AW in CKRT patients.57 Options include adding phosphate to CKRT solutions or using commercially available dextrose-free solutions containing phosphate. Multiple centers, including those using regional citrate anticoagulation, have reported that either option can effectively mitigate hypophosphatemia without effects on solute control apart from modest degrees of hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, and metabolic acidosis.67,78,79 Moreover, in a retrospective before-and-after study at one of our centers, the use of phosphate-containing CKRT solutions was independently associated with decreased durations of mechanical ventilation and ICU and hospital LOS without impact on mortality.67,78 Though promising, prospective interventional data on phosphate-containing CKRT solutions and outcomes are needed. An alternative to adding phosphate to CKRT solutions to mitigate CKRT-induced hypophosphatemia is to implement preemptive enteral or intravenous phosphate replacement as soon as serum phosphate levels fall to within normal limits, often 24–48h after CKRT initiation.57

The optimal approach to replacement of other electrolytes in CKRT patients appears less clear. Though typically standard of care, data on the benefits of treating or preventing CKRT-induced hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, or hypokalemia – beyond normalizing serum levels – are lacking.80,81 Interestingly, some animal and observational human data suggest harm from calcium supplementation in the setting of sepsis or general critical illness,82–84 but the relevance of these observations to KRT patients is unclear.

Similarly, though nutrition is essential supportive care in the ICU, the optimal nutritional approach to mitigate ICU-AW in patients with AKI or AKI-KRT is unclear. Despite some data suggesting that standard approaches to estimating nutritional needs perform poorly in critically ill AKI patients,85 guidelines recommend, based on low-quality evidence, that AKI patients receive the same targets as other ICU patients for protein (1.2–2 g/kg/day) and total calories (25–30 kcal/kg/day).86 In patients requiring CKRT or frequent KRT, additional protein supplementation up to 2.5 g/kg/day is recommended to counteract AA loss.86 Notably, secondary outcomes of some large RCTs of nutrition in the ICU suggest that earlier initiation of supplemental nutrition and/or higher caloric intake may be associated with prolonged need for KRT or delayed kidney recovery.87,88 Furthermore, higher protein intake has not been convincingly associated with improved outcomes in general ICU populations, with a recent meta-analysis demonstrating attenuation of muscle loss but no impact on measured muscle strength, QoL, discharge destination, or mortality.89 Likewise, a recent study of 15 ICU patients demonstrated impaired incorporation of nutritional AAs into skeletal muscle despite normal enteral protein digestion and absorption.90 High-quality prospective data on optimal nutrition for ICU patients with AKI or AKI-KRT are needed.

Physical rehabilitation/early mobilization to mitigate ICU-AW in patients with AKI

Early mobilization, physical rehabilitation, and exercise are the primary approaches to reducing the detrimental effects of prolonged immobilization or bedrest.91 Multiple factors have been proposed as barriers to early mobilization in the ICU including vasopressor and sedative use and, in AKI-KRT patients, the presence of vascular catheters and ongoing KRT.92 However, clinical practice and recent research have demonstrated that these barriers can be overcome.93–95 Strategies that we and others have reported include disconnection from the KRT circuit during mobilization, extensions placed on KRT lines, portable batteries to mobilize patients with KRT machines, and temporarily adjusting the KRT prescription (e.g., to recirculation mode or to pause net ultrafiltration) to facilitate rehabilitation.94

Catheter type (i.e., non-tunneled vs tunneled) and access site (i.e., femoral vs jugular) may influence the perceived feasibility of mobilizing KRT patients.93 However, in one prospective study, 77 patients with a total of 92 femoral venous or arterial catheters suffered no catheter-related complications during mobility sessions including hip flexion.96 Another study of 101 ICU patients with femoral catheters receiving 253 therapy sessions, including standing, walking, sitting, supine cycle ergometry, and in-bed exercises, reported no catheter-related adverse events.97 Collectively, these data suggest that mobilization of ICU patients with femoral catheters is feasible and safe.

We recently performed a systematic review analyzing adverse events, both major (i.e., catheter dislodgement, accidental extubation, bleeding, fall, hemodynamic emergency) and minor (i.e., desaturation, hypotension, bradycardia, tachycardia), reported in 10 observational studies involving 840 mobility sessions during CKRT and found pooled rates of 1.6% and 0.2% for minor and major adverse events, respectively.95 Finally, the 2014 expert recommendations on safety criteria for active mobilization of mechanically ventilated adults concluded that in-bed or out-of-bed exercises can be performed during CKRT with low risk of adverse events.98 Though it seems probable that early mobilization in CKRT patients would have a meaningful benefit on outcomes, randomized trials to prove this hypothesis are lacking.

Post-discharge care for ICU-AW in AKI survivors

Advancements in intensive care have led to increasing survival over the past two decades,99 but ICU survivors also often face significant impairments in cognitive, emotional, and physical health. Post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) encompasses the development or exacerbation of symptoms or impairments after critical illness in the cognitive,100 psychiatric,101 or physical25 domains and has become an increasing focus of post-discharge care being provided in multidisciplinary PICS clinics. Though some benefit in terms of decreased readmissions and PTSD has been demonstrated,102,103 no studies thus far have demonstrated improvements in functional status through rehabilitation provided by these clinics.

Similarly, dedicated post-AKI clinics have increased in number over the past decade, and tailored outpatient nephrology follow-up has been advocated as an intervention to improve post-AKI outcomes.104 Observational data105,106 suggest that early nephrology follow-up after AKI improves outcomes, though prospective studies thus far have been scarce and have produced mixed results,107 supporting the need for further interventional trials.

No data exist on how to best address persistent ICU-AW in AKI survivors, but we propose nephrologists providing post-AKI ambulatory care should, at a minimum, recognize these patients as being at high risk of long-term functional impairment and, where feasible, consider referral to physical and occupational therapy for evaluation and treatment. Future studies should therefore investigate whether providing rehabilitation is useful in addressing long-term physical impairments in AKI survivors and, if so, how to best deliver such care. One novel model could be to provide post-AKI nephrology visits within or in coordination with multidisciplinary PICS clinics, which could potentially improve the feasibility of providing systematic post-AKI care.107 Alternatively, for AKI patients requiring post-discharge outpatient KRT, providing rehabilitation services or exercise training during hemodialysis, similar to interventions that have proven to some degree to be beneficial in kidney failure,108 could prove effective.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Critically ill patients who develop AKI are at high risk of skeletal muscle loss and dysfunction and associated long-term impairments in physical function and QoL. The need for acute KRT likely further exacerbates the risk of ICU-AW. Nephrologists must work with ICU teams to address potentially modifiable risk factors for ICU-AW and coordinate multidisciplinary care to optimize delivery of rehabilitation. The development of KRT quality assurance teams,109 which advocate for excellence in KRT and create protocols to prevent complications such as hypophosphatemia, optimize nutritional support, and enhance delivery of physical therapy, may mitigate the burden of ICU-AW in patients with AKI-KRT. Furthermore, though data to support such approaches remain limited, advances in proteomics and metabolomics may further enhance our understanding of how ICU patients adapt to extracorporeal therapies that non-selectively clear solutes. Specifically, improved characterization of the resulting metabolic derangements through analyses of tissue, blood, and effluent could promote the development of precision medicine approaches to reestablishing homeostasis in critically ill patients with AKI-KRT. In conclusion, additional experimental research and clinical trials are direly needed to better understand the mechanisms that link critical illness, AKI, and KRT to ICU-AW and to ultimately develop and validate treatment strategies to prevent and mitigate ICU-AW in these high-risk patients.

Support:

JPT, KPM, BRG, and JAN have received funding for related research from NCATS (CORES grant U24TR002260) and our local respective NIH CTSA program grants (University of Kentucky CTSA, UL1TR001998; University of New Mexico CTSC, UL1TR001449; and University of Iowa ICTS, UL1TR002537). These funding sources had no role in the conceptualization or realization of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.Griffin BR, Liu KD, Teixeira JP. Critical Care Nephrology: Core Curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. Mar 2020;75(3):435–452. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoste EA, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: the multinational AKI-EPI study. Intensive Care Med. Aug 2015;41(8):1411–23. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3934-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouchard J, Acharya A, Cerda J, et al. A Prospective International Multicenter Study of AKI in the Intensive Care Unit. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Aug 7 2015;10(8):1324–31. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04360514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald R, McArthur E, Adhikari NK, et al. Changing incidence and outcomes following dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury among critically ill adults: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. Jun 2015;65(6):870–7. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown JR, Rezaee ME, Marshall EJ, Matheny ME. Hospital Mortality in the United States following Acute Kidney Injury. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4278579. doi: 10.1155/2016/4278579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan L, Chaudhary K, Saha A, et al. AKI in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. J Am Soc Nephrol. Jan 2021;32(1):151–160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020050615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teixeira JP, Ambruso S, Griffin BR, Faubel S. Pulmonary Consequences of Acute Kidney Injury. Semin Nephrol. Jan 2019;39(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clermont G, Acker CG, Angus DC, Sirio CA, Pinsky MR, Johnson JP. Renal failure in the ICU: comparison of the impact of acute renal failure and end-stage renal disease on ICU outcomes. Kidney Int. Sep 2002;62(3):986–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Investigators RRTS, Bellomo R, Cass A, et al. Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. Oct 22 2009;361(17):1627–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Network VNARFT, Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, et al. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. Jul 3 2008;359(1):7–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahlstrom A, Tallgren M, Peltonen S, Rasanen P, Pettila V. Survival and quality of life of patients requiring acute renal replacement therapy. Intensive Care Med. Sep 2005;31(9):1222–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2681-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansen KL, Smith MW, Unruh ML, et al. Predictors of health utility among 60-day survivors of acute kidney injury in the Veterans Affairs/National Institutes of Health Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Aug 2010;5(8):1366–72. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02570310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayer KP, Ortiz-Soriano VM, Kalantar A, Lambert J, Morris PE, Neyra JA. Acute kidney injury contributes to worse physical and quality of life outcomes in survivors of critical illness. BMC Nephrol. Apr 7 2022;23(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12882-022-02749-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosla N, Soroko SB, Chertow GM, et al. Preexisting chronic kidney disease: a potential for improved outcomes from acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Dec 2009;4(12):1914–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01690309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neyra JA, Mescia F, Li X, et al. Impact of Acute Kidney Injury and CKD on Adverse Outcomes in Critically Ill Septic Patients. Kidney Int Rep. Nov 2018;3(6):1344–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2018.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latronico N, Herridge M, Hopkins RO, et al. The ICM research agenda on intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med. Mar 13 2017;doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4757-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appleton RT, Kinsella J, Quasim T. The incidence of intensive care unit-acquired weakness syndromes: A systematic review. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2015;16(2):126–136. doi: 10.1177/1751143714563016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coakley JH, Nagendran K, Yarwood GD, Honavar M, Hinds CJ. Patterns of neurophysiological abnormality in prolonged critical illness. Intensive Care Med. Aug 1998;24(8):801–7. doi: 10.1007/s001340050669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Files DC, Sanchez MA, Morris PE. A conceptual framework: the early and late phases of skeletal muscle dysfunction in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical care (London, England). Jul 02 2015;19:266. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0979-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer KP, Thompson Bastin ML, Montgomery-Yates AA, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting and dysfunction predict physical disability at hospital discharge in patients with critical illness. Critical Care. 2020/11/04 2020;24(1):637. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03355-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parry SM, El-Ansary D, Cartwright MS, et al. Ultrasonography in the intensive care setting can be used to detect changes in the quality and quantity of muscle and is related to muscle strength and function. Journal of critical care. Oct 2015;30(5):1151.e9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puthucheary ZA, Phadke R, Rawal J, et al. Qualitative Ultrasound in Acute Critical Illness Muscle Wasting. Crit Care Med. Aug 2015;43(8):1603–11. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000001016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. Jama. Oct 16 2013;310(15):1591–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermans G, Van Mechelen H, Clerckx B, et al. Acute outcomes and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. Aug 15 2014;190(4):410–20. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2257OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. Apr 7 2011;364(14):1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jolley SE, Bunnell AE, Hough CL. ICU-Acquired Weakness. Chest. Nov 2016;150(5):1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raurell-Torreda M, Arias-Rivera S, Marti JD, et al. Care and treatments related to intensive care unit-acquired muscle weakness: A cohort study. Aust Crit Care. Mar 1 2021;doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens RD, Marshall SA, Cornblath DR, et al. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Crit Care Med. Oct 2009;37(10 Suppl):S299–308. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6ef67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parry SM, Berney S, Granger CL, et al. A new two-tier strength assessment approach to the diagnosis of weakness in intensive care: an observational study. Critical care (London, England). Feb 26 2015;19:52. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0780-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambell KJ, Tierney AC, Wang JC, et al. Comparison of Ultrasound-Derived Muscle Thickness With Computed Tomography Muscle Cross-Sectional Area on Admission to the Intensive Care Unit: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 01 2021;45(1):136–145. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Llano-Diez M, Renaud G, Andersson M, et al. Mechanisms underlying ICU muscle wasting and effects of passive mechanical loading. Crit Care. Oct 26 2012;16(5):R209. doi: 10.1186/cc11841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coles GA. Body composition in chronic renal failure. Q J Med. Jan 1972;41(161):25–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solagna F, Tezze C, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Pro-cachectic factors link experimental and human chronic kidney disease to skeletal muscle wasting programs. J Clin Invest. Jun 1 2021;131(11)doi: 10.1172/JCI135821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XH, Mitch WE. Mechanisms of muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. Sep 2014;10(9):504–16. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandri M. Protein breakdown in muscle wasting: role of autophagy-lysosome and ubiquitin-proteasome. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. Oct 2013;45(10):2121–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andres-Hernando A, Altmann C, Bhargava R, et al. Prolonged acute kidney injury exacerbates lung inflammation at 7 days post-acute kidney injury. Physiol Rep. Jul 1 2014;2(7)doi: 10.14814/phy2.12084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly KJ. Distant effects of experimental renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. Jun 2003;14(6):1549–58. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000064946.94590.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox BM, Gil HW, Kirkbride-Romeo L, et al. Metabolomics assessment reveals oxidative stress and altered energy production in the heart after ischemic acute kidney injury in mice. Kidney Int. 03 2019;95(3):590–610. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goodman MN. Interleukin-6 induces skeletal muscle protein breakdown in rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. Feb 1994;205(2):182–5. doi: 10.3181/00379727-205-43695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Almushayt SJ, Hussain S, Wilkinson DJ, Selby NM. A Systematic Review of the Acute Effects of Hemodialysis on Skeletal Muscle Perfusion, Metabolism, and Function. Kidney Int Rep. Mar 2020;5(3):307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolfson M, Jones MR, Kopple JD. Amino acid losses during hemodialysis with infusion of amino acids and glucose. Kidney Int. Mar 1982;21(3):500–6. doi: 10.1038/ki.1982.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chazot C, Shahmir E, Matias B, Laidlaw S, Kopple JD. Dialytic nutrition: provision of amino acids in dialysate during hemodialysis. Kidney Int. Dec 1997;52(6):1663–70. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davenport A, Roberts NB. Amino acid losses during continuous high-flux hemofiltration in the critically ill patient. Crit Care Med. Oct 1989;17(10):1010–4. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198910000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davies SP, Reaveley DA, Brown EA, Kox WJ. Amino acid clearances and daily losses in patients with acute renal failure treated by continuous arteriovenous hemodialysis. Crit Care Med. Dec 1991;19(12):1510–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199112000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frankenfield DC, Badellino MM, Reynolds HN, Wiles CE 3rd, Siegel JH, Goodarzi S. Amino acid loss and plasma concentration during continuous hemodiafiltration. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. Nov-Dec 1993;17(6):551–61. doi: 10.1177/0148607193017006551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mokrzycki MH, Kaplan AA. Protein losses in continuous renal replacement therapies. J Am Soc Nephrol. Oct 1996;7(10):2259–63. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7102259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kihara M, Ikeda Y, Fujita H, et al. Amino acid losses and nitrogen balance during slow diurnal hemodialysis in critically ill patients with renal failure. Intensive Care Med. Jan 1997;23(1):110–3. doi: 10.1007/s001340050299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novak I, Sramek V, Pittrova H, et al. Glutamine and other amino acid losses during continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration. Artif Organs. May 1997;21(5):359–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.1997.tb00731.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheinkestel CD, Adams F, Mahony L, et al. Impact of increasing parenteral protein loads on amino acid levels and balance in critically ill anuric patients on continuous renal replacement therapy. Nutrition. Sep 2003;19(9):733–40. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(03)00107-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chua HR, Baldwin I, Fealy N, Naka T, Bellomo R. Amino acid balance with extended daily diafiltration in acute kidney injury. Blood Purif. 2012;33(4):292–9. doi: 10.1159/000335607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt JJ, Hafer C, Spielmann J, et al. Removal characteristics and total dialysate content of glutamine and other amino acids in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury undergoing extended dialysis. Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;126(1):62–6. doi: 10.1159/000358434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Umber A, Wolley MJ, Golper TA, Shaver MJ, Marshall MR. Amino acid losses during sustained low efficiency dialysis in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Clin Nephrol. Feb 2014;81(2):93–9. doi: 10.5414/CN107982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stapel SN, de Boer RJ, Thoral PJ, Vervloet MG, Girbes ARJ, Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Amino Acid Loss during Continuous Venovenous Hemofiltration in Critically Ill Patients. Blood Purif. 2019;48(4):321–329. doi: 10.1159/000500998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oh WC, Mafrici B, Rigby M, et al. Micronutrient and Amino Acid Losses During Renal Replacement Therapy for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Rep. Aug 2019;4(8):1094–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ostermann M, Summers J, Lei K, et al. Micronutrients in critically ill patients with severe acute kidney injury - a prospective study. Sci Rep. Jan 30 2020;10(1):1505. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58115-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Griffin BR, Ray M, Rolloff K, et al. Plasma Metabolites Do Not Change Significantly After 48 Hours in Patients on CRRT [abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(Suppl):81. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heung M, Mueller BA. Prevention of hypophosphatemia during continuous renal replacement therapy-An overlooked problem. Semin Dial. May 2018;31(3):213–218. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma S, Brugnara C, Betensky RA, Waikar SS. Reductions in red blood cell 2,3-diphosphoglycerate concentration during continuous renal replacment therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Jan 7 2015;10(1):74–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02160214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bollaert PE, Levy B, Nace L, Laterre PF, Larcan A. Hemodynamic and metabolic effects of rapid correction of hypophosphatemia in patients with septic shock. Chest. Jun 1995;107(6):1698–701. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.6.1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim C, Tan HK, Kaushik M. Hypophosphatemia in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury treated with hemodialysis is associated with adverse events. Clin Kidney J. Jun 2017;10(3):341–347. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McIntire KL, Chen Y, Sood S, Rabkin R. Acute uremia suppresses leucine-induced signal transduction in skeletal muscle. Kidney Int. Feb 2014;85(2):374–82. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aniort J, Polge C, Claustre A, et al. Upregulation of MuRF1 and MAFbx participates to muscle wasting upon gentamicin-induced acute kidney injury. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. Oct 2016;79:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagata S, Kato A, Isobe S, et al. Regular exercise and branched-chain amino acids prevent ischemic acute kidney injury-related muscle wasting in mice. Physiol Rep. Aug 2020;8(16):e14557. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aubier M, Murciano D, Lecocguic Y, et al. Effect of hypophosphatemia on diaphragmatic contractility in patients with acute respiratory failure. The New England journal of medicine. Aug 15 1985;313(7):420–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508153130705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sharma S, Kelly YP, Palevsky PM, Waikar SS. Intensity of Renal Replacement Therapy and Duration of Mechanical Ventilation: Secondary Analysis of the Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study. Chest. Oct 2020;158(4):1473–1481. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Demirjian S, Teo BW, Guzman JA, et al. Hypophosphatemia during continuous hemodialysis is associated with prolonged respiratory failure in patients with acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. Nov 2011;26(11):3508–14. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thompson Bastin ML, Stromberg AJ, Nerusu SN, et al. Association of Phosphate-Containing versus Phosphate-Free Solutions on Ventilator Days in Patients Requiring Continuous Kidney Replacement Therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Apr 27 2022;doi: 10.2215/CJN.12410921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hendrix RJ, Hastings MC, Samarin M, Hudson JQ. Predictors of Hypophosphatemia and Outcomes during Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Blood Purif. 2020;49(6):700–707. doi: 10.1159/000507421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang Y, Zhang P, Cui Y, et al. Hypophosphatemia during continuous veno-venous hemofiltration is associated with mortality in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Critical care (London, England). Sep 19 2013;17(5):R205. doi: 10.1186/cc12900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bellomo R, Cass A, Cole L, et al. The relationship between hypophosphataemia and outcomes during low-intensity and high-intensity continuous renal replacement therapy. Crit Care Resusc. Mar 2014;16(1):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brain M, Anderson M, Parkes S, Fowler P. Magnesium flux during continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration with heparin and citrate anticoagulation. Crit Care Resusc. Dec 2012;14(4):274–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dhingra S, Solven F, Wilson A, McCarthy DS. Hypomagnesemia and respiratory muscle power. Am Rev Respir Dis. Mar 1984;129(3):497–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aubier M, Viires N, Piquet J, et al. Effects of hypocalcemia on diaphragmatic strength generation. J Appl Physiol (1985). Jun 1985;58(6):2054–61. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.6.2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang P, Lv Q, Lai T, Xu F. Does Hypomagnesemia Impact on the Outcome of Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Shock. Mar 2017;47(3):288–295. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Afshinnia F, Belanger K, Palevsky PM, Young EW. Effect of ionized serum calcium on outcomes in acute kidney injury needing renal replacement therapy: secondary analysis of the acute renal failure trial network study. Ren Fail. 2013;35(10):1310–8. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.828258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Chewcharat A, Mao MA, Kashani KB. Serum ionised calcium and the risk of acute respiratory failure in hospitalised patients: a single-centre cohort study in the USA. BMJ Open. Mar 23 2020;10(3):e034325. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Radhakrishnan Y, et al. Association of serum potassium derangements with mortality among patients requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Ther Apher Dial. Jan 22 2022;doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.13804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thompson Bastin ML, Adams PM, Nerusu S, Morris PE, Mayer KP, Neyra JA. Association of Phosphate Containing Solutions with Incident Hypophosphatemia in Critically Ill Patients Requiring Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Blood Purif. Apr 29 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000514418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chua HR, Baldwin I, Ho L, Collins A, Allsep H, Bellomo R. Biochemical effects of phosphate-containing replacement fluid for continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Blood Purif. 2012;34(3–4):306–12. doi: 10.1159/000345343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zakharchenko M, Los F, Brodska H, Balik M. The Effects of High Level Magnesium Dialysis/Substitution Fluid on Magnesium Homeostasis under Regional Citrate Anticoagulation in Critically Ill. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158179. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Di Mario F, Regolisti G, Greco P, et al. Prevention of hypomagnesemia in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury on continuous kidney replacement therapy: the role of early supplementation and close monitoring. J Nephrol. Aug 2021;34(4):1271–1279. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00864-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Aberegg SK. Ionized Calcium in the ICU: Should It Be Measured and Corrected? Chest. Mar 2016;149(3):846–55. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Collage RD, Howell GM, Zhang X, et al. Calcium supplementation during sepsis exacerbates organ failure and mortality via calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase signaling. Crit Care Med. Nov 2013;41(11):e352–60. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dotson B, Larabell P, Patel JU, et al. Calcium Administration Is Associated with Adverse Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Parenteral Nutrition: Results from a Natural Experiment Created by a Calcium Gluconate Shortage. Pharmacotherapy. Nov 2016;36(11):1185–1190. doi: 10.1002/phar.1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hellerman M, Sabatino A, Theilla M, Kagan I, Fiaccadori E, Singer P. Carbohydrate and Lipid Prescription, Administration, and Oxidation in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury: A Post Hoc Analysis. J Ren Nutr. Jul 2019;29(4):289–294. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. Feb 2016;40(2):159–211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gunst J, Vanhorebeek I, Casaer MP, et al. Impact of early parenteral nutrition on metabolism and kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 2013;24(6):995–1005. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Haddad SH, et al. Permissive Underfeeding or Standard Enteral Feeding in Critically Ill Adults. The New England journal of medicine. Jun 18 2015;372(25):2398–408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee ZY, Yap CSL, Hasan MS, et al. The effect of higher versus lower protein delivery in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Critical care (London, England). Jul 23 2021;25(1):260. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03693-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chapple LS, Kouw IWK, Summers MJ, et al. Muscle Protein Synthesis Following Protein Administration in Critical Illness. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. May 18 2022;doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2780OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang YT, Lang JK, Haines KJ, Skinner EH, Haines TP. Physical Rehabilitation in the ICU: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. Aug 18 2021;doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dubb R, Nydahl P, Hermes C, et al. Barriers and Strategies for Early Mobilization of Patients in Intensive Care Units. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. May 2016;13(5):724–30. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-586CME [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toonstra AL, Zanni JM, Sperati CJ, et al. Feasibility and Safety of Physical Therapy during Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. May 2016;13(5):699–704. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201506-359OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mayer KP, Hornsby AR, Soriano VO, et al. Safety, feasibility, and efficacy of early rehabilitation in patients requiring continuous renal replacement: A quality improvement study. Kidney International Reports. 2019;doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mayer KP, Joseph-Isang E, Robinson LE, Parry SM, Morris PE, Neyra JA. Safety and Feasibility of Physical Rehabilitation and Active Mobilization in Patients Requiring Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med. Nov 2020;48(11):e1112–e1120. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Perme C, Nalty T, Winkelman C, Kenji Nawa R, Masud F. Safety and Efficacy of Mobility Interventions in Patients with Femoral Catheters in the ICU: A Prospective Observational Study. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2013;24(2):12–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Damluji A, Zanni JM, Mantheiy E, Colantuoni E, Kho ME, Needham DM. Safety and feasibility of femoral catheters during physical rehabilitation in the intensive care unit. Journal of critical care. Aug 2013;28(4):535.e9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hodgson CL, Stiller K, Needham DM, et al. Expert consensus and recommendations on safety criteria for active mobilization of mechanically ventilated critically ill adults. Critical care (London, England). 2014;18(6):658. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0658-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, Knaus WA. Changes in hospital mortality for United States intensive care unit admissions from 1988 to 2012. Critical care (London, England). 2013;17(2):R81–R81. doi: 10.1186/cc12695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Ely EW. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. The New England journal of medicine. Jan 9 2014;370(2):185–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive Symptoms After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Care Med. Sep 2016;44(9):1744–53. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000001811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bloom SL, Stollings JL, Kirkpatrick O, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of an ICU Recovery Pilot Program for Survivors of Critical Illness. Crit Care Med. Oct 2019;47(10):1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jensen JF, Thomsen T, Overgaard D, Bestle MH, Christensen D, Egerod I. Impact of follow-up consultations for ICU survivors on post-ICU syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. May 2015;41(5):763–75. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3689-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Silver SA, Wald R. Improving outcomes of acute kidney injury survivors. Curr Opin Crit Care. Dec 2015;21(6):500–5. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harel Z, Wald R, Bargman JM, et al. Nephrologist follow-up improves all-cause mortality of severe acute kidney injury survivors. Kidney Int. May 2013;83(5):901–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ly H, Ortiz-Soriano V, Liu LJ, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Survivors of Critical Illness and Acute Kidney Injury Followed in a Pilot Acute Kidney Injury Clinic. Kidney Int Rep. Dec 2021;6(12):3070–3073. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Silver S, Adhikari N, Bell C, et al. Nephrologist Follow-Up versus Usual Care after an Acute Kidney Injury Hospitalization (FUSION). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. May 21 2021;doi: 10.2215/CJN.17331120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Barcellos FC, Santos IS, Umpierre D, Bohlke M, Hallal PC. Effects of exercise in the whole spectrum of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Clin Kidney J. Dec 2015;8(6):753–65. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfv099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ruiz EF, Ortiz-Soriano VM, Talbott M, et al. Development, implementation and outcomes of a quality assurance system for the provision of continuous renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. Sci Rep. Nov 26 2020;10(1):20616. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76785-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baldwin CE, Paratz JD, Bersten AD. Muscle strength assessment in critically ill patients with handheld dynamometry: an investigation of reliability, minimal detectable change, and time to peak force generation. Journal of critical care. Feb 2013;28(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kennouche D, Luneau E, Lapole T, Morel J, Millet GY, Gondin J. Bedside voluntary and evoked forces evaluation in intensive care unit patients: a narrative review. Critical care (London, England). Apr 22 2021;25(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03567-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mitch WE. Amino acid release from the hindquarter and urea appearance in acute uremia. Am J Physiol. Dec 1981;241(6):E415–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1981.241.6.E415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Clark AS, Mitch WE. Muscle protein turnover and glucose uptake in acutely uremic rats. Effects of insulin and the duration of renal insufficiency. J Clin Invest. Sep 1983;72(3):836–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI111054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.May RC, Clark AS, Goheer MA, Mitch WE. Specific defects in insulin-mediated muscle metabolism in acute uremia. Kidney Int. Sep 1985;28(3):490–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Flugel-Link RM, Salusky IB, Jones MR, Kopple JD. Protein and amino acid metabolism in posterior hemicorpus of acutely uremic rats. Am J Physiol. Jun 1983;244(6):E615–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1983.244.6.E615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Baliga R, Shah SV. Effects of dietary protein intake on muscle protein synthesis and degradation in rats with gentamicin-induced acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. May 1991;1(11):1230–5. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1111230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Price SR, Reaich D, Marinovic AC, et al. Mechanisms contributing to muscle-wasting in acute uremia: activation of amino acid catabolism. J Am Soc Nephrol. Mar 1998;9(3):439–43. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V93439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]