Abstract

Objectives

A patient's death by suicide is a common experience for psychiatrists, ranging from 33% to 80%, however, research about the impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists is limited to a few survey studies. This study had three main objectives: (1) understanding the emotional and behavioural impact of a patient's suicide on psychiatrists, (2) exploring if and how the experience of a patient's suicide results in changes in psychiatrist practice patterns, and (3) understanding the tangible steps that psychiatrists and institutions take to manage the emotional and behavioural impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists.

Methods

Eighteen psychiatrists were recruited using snowball sampling and interviewed to collect demographic data, followed by an in-depth exploration of their experiences of patient suicide. Interviews were then transcribed verbatim and analysed using constructivist grounded theory.

Results

Study participants described strong emotional reactions in response to patient suicide. Emotional reactions were mediated by a physician, patient, relationship and institutional factors. While psychiatrists did not change the acuity or setting of their practice in response to patient suicide, they made several changes in their practice, including increased caution regarding discharges and passes from inpatient units, more thorough documentation and continuing education about suicide.

Conclusions

Patient suicide has a profound impact on psychiatrists and based on the findings of this study, we propose steps that psychiatrists and institutions can take to manage the emotional, psychological and behavioural burden of this event.

Keywords: suicide, qualitative, mental health services

Abstract

Objectifs

Le décès d’un patient par suicide est une expérience commune pour les psychiatres, allant de 33 % à 80 %. Cependant, la recherche sur l’effet du suicide d’un patient sur les psychiatres se limite à quelques études par sondage. La présente étude visait trois objectifs principaux : 1) comprendre l’effet émotionnel et comportemental du suicide d’un patient sur les psychiatres, 2) explorer si et comment l’expérience du suicide d’un patient résulte en des changements du mode de pratique du psychiatre et 3) comprendre les mesures concrètes que prennent les psychiatres et les institutions pour prendre en charge l’effet émotionnel et comportemental du suicide du patient sur les psychiatres.

Méthodes

Dix-huit psychiatres ont été recrutés à l’aide de l’échantillonnage en boule de neige et ont été interviewés pour recueillir des données démographiques, suivi d’une exploration en profondeur de leurs expériences de suicide d’un patient. Les interviews ont ensuite été transcrites textuellement et analysées à l’aide de la théorie constructiviste ancrée.

Résultats

Les participants à l’étude ont décrit de fortes réactions émotionnelles en réponse au suicide du patient. Les réactions émotionnelles étaient provoquées par le médecin, le patient, la relation et les facteurs institutionnels. Bien que les psychiatres n’aient pas changé l’acuité ou le cadre de leur pratique en réponse au suicide du patient, ils ont fait plusieurs changements à leur pratique, notamment une attention accrue aux congés et aux permis des unités de patients hospitalisés, plus de documentation fouillée et d’éducation permanente sur le suicide.

Conclusions

Le suicide d’un patient a un effet profond sur les psychiatres, et selon les résultats de la présente étude, nous proposons des mesures que peuvent prendre les psychiatres et les institutions pour prendre en charge le poids émotionnel, psychologique et comportemental de cet événement.

Introduction

Suicide is among the top 10 causes of death in North America and one of the most common causes of death among psychiatric patients.1,2 Approximately 33% to 80% of psychiatrists experience the death of a patient by suicide.3,4 However, our knowledge about the impact of a patient's suicide on psychiatrists’ emotional well-being and clinical practice is limited to a few survey studies and minimal qualitative data.

Survey studies have indicated that psychiatrists experience strong emotional reactions to a patient dying by suicide. Reactions include disbelief, self-doubt, embarrassment, guilt, self-blame, anger, and shock, as well as fear and anxiety over personal or legal repercussions.3,5–8 Many also experience low mood, irritability and poor sleep. 3 Clinicians also experience stress about communicating with their patients’ families following the suicide due to fear of litigation, confidentiality breaches, and the emotional impact on family members and psychiatrists themselves. 4

A small number of studies discuss the impact of a patient's suicide on psychiatrists’ practices, which can include adaptive changes, such as more frequent consultation and supervision, and maladaptive changes, such as adopting more defensive treatment approaches for patients at risk of suicide.3,7,9 One qualitative research article focuses on how psychiatrists unburden themselves from grief in the face of patient suicide. 10 Comparatively, there is a more substantial body of qualitative research on allied health professionals’ experiences of and responses to patient suicide.11–13 This study had three main objectives: (1) understanding the emotional and behavioural impact of a patient's suicide on psychiatrists, (2) exploring if and how the experience of a patient's suicide results in changes in psychiatrist practice patterns, and (3) understanding the tangible steps that psychiatrists and institutions take to manage the emotional and behavioural impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists.

Methods

We followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) to present this study 14 (Appendix A). This study was approved by the Research and Ethics Board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada. The principles of constructivist grounded theory (CGT) were used both to design this study and to analyse the data. Grounded theory is a systematic qualitative research methodology that emphasizes the generation of theory rooted in data through inductive reasoning, 15 while CGT is a variant of grounded theory which emphasizes that reality is co-constructed between participants and researchers. CGT allows researchers to develop hypotheses and questions based on the existing literature. 16

Data Collection

All psychiatrists in the Greater Toronto Area who had a history of providing direct clinical care to a patient who died by suicide were invited to participate in the study. After the initial round of recruiting through email and social media platforms, which recruited 10 participants, a snowball sampling strategy was then employed to recruit eight additional participants, for a total of 18 participants. Exponential discriminative snowball sampling refers to recruiting a limited number of new subjects from referrals; the choice of a new subject is guided by the aims of the study. 17

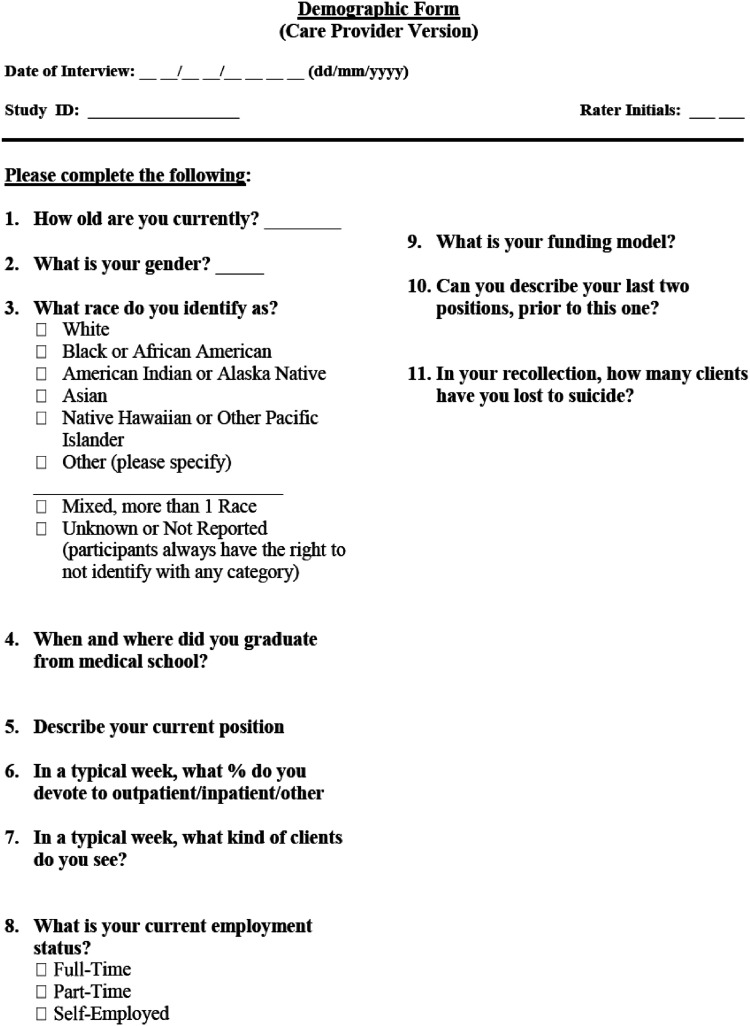

After informed consent was obtained, each participant completed a short questionnaire which included demographic information and characteristics of the participant's practice (Appendix B). Subsequently, each participant was interviewed for approximately 60–90 min using a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix C). A life history approach was taken to interviewing, with a particular emphasis on professional life histories. 18 After establishing context, participants were asked about their experiences of a patient's death by suicide. Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and de-identified.

Analysis

Due to technical issues, the recording of one interview was inaccessible. Therefore, 17 interviews were analysed using qualitative analysis. All transcripts were reviewed in-depth by authors ZF, RC and JZ. Using NVIVO (qualitative analysis software), ZF engaged in line-by-line coding of the first 4 transcripts, known as “open coding.” Codes were then organized into broad categories, a process known as axial coding. 16 After open coding the first four transcripts, no new categories of codes were being created from the data, a point known as “thematic saturation.” Code categories that were useful in answering the research questions were chosen to develop a coding tree (Appendix D). Examples of the code categories include “Emotional responses to patient suicide” and “Impact on professional practice.” This coding tree was shared with and reviewed by the team. Only sections of the remaining 14 transcripts pertaining to the coding tree were coded; this is a strategy known as “focused coding,” which is recommended for analysing and sifting through large amounts of data. 16

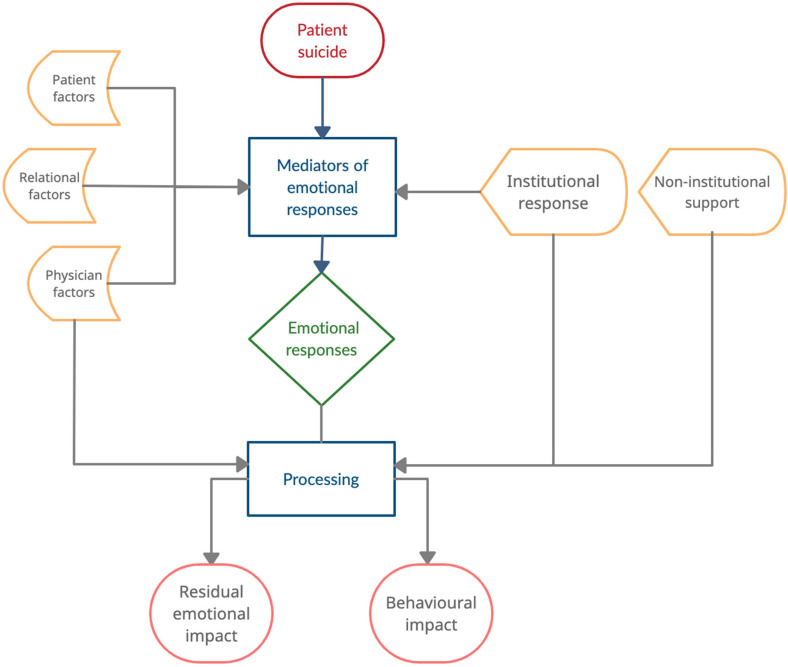

To ensure credibility, monthly meetings were held between ZF and JZ to ensure quality control, and explore emergent themes and memo-writing, which is “the process of elaborating processes, assumptions and actions captured in codes and categories.” 16 For example, through memo-writing, the authors commented on links between certain patient characteristics and the emotional reactions the participants described. JZ would review both the transcript and the codes to ensure that the codes were true to the data. After coding and memos were completed for all transcripts, meetings were held between all team members, to discuss the connections between categories, facilitated by memos. These connections were diagrammed and a model was created to visualize the process by which a patient's suicide is experienced (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Processing the death of a patient by suicide.

Researcher Characteristics and Reflexivity

Multiple members of the research team are practicing psychiatrists, many of whom have experienced the death of a patient by suicide. Many team members are also part of institutions and hospitals which are responsible for supporting psychiatrists after patient suicides. These potential sources of bias were discussed among team members and taken into consideration during data collection and analysis.

Results

Characterizing the Sample

Our sample initially included 18 psychiatrists. The demographic information for all 18 is presented in Table 1, though only 17 interviews were available for qualitative analysis. All participants experienced at least one patient suicide during their time as staff psychiatrists. Twelve participants also experienced the death of a patient by suicide during their residency training. While the ethnic backgrounds of the participants were collected, due to the small sample size, multiple categories of ethnicities included <3 participants. To protect the identities of our participants, we collapsed the categories to “White/Caucasian” and “Racialized minority.”

Table 1.

Demographic and Professional Information.

| Gender | Men: 7 |

| Women:11 | |

| Age (in years) | Average: 46.1 |

| Range: 34 − 70 | |

| SD: 11.6 | |

| Years in practice at the time of the interview | Average:13.8 |

| Range: 3 − 41 | |

| SD: 12.0 | |

| Patient population* | General psychiatry: 11 |

| Child and adolescent: 3 | |

| Consult liaison: 3 | |

| Other: 6 | |

| Type of practice* (current) |

Inpatient: 7 |

| Outpatient: 16 | |

| Consult Liaison: 3 | |

| Psychotherapy: 6 | |

| Admin: 3 | |

| Research: 4 | |

| Type of practice* (over course of a career) |

Inpatient: 12 |

| Outpatient: 18 | |

| Consult liaison: 4 | |

| Psychotherapy: 6 | |

| Admin: 6 | |

| Research: 7 | |

| Location of practice* | Academic Hospital:14 |

| Community Hospital: 4 | |

| Mixed hospital and private: 2 | |

| Race | White/Caucasian: 12 |

| Racialized minority: 6 |

* Participants were allowed to indicate multiple responses.

Qualitative Findings

In the following sections, we present a model (Figure 1) for understanding the experiences of psychiatrists who experience the death of a patient by suicide. Our data indicates that the experience of patient suicide is a process rather than an event. This process is conceptualized as the model in Figure 1. Multiple factors influence this process and mitigate emotional and behavioural outcomes. We present a breakdown of each theme represented in our model, using sample quotations from the participants.

Emotional Responses to Patient Suicide

Grief and Sadness

Fifteen out of the 17 psychiatrists expressed grief and sadness after the death of a patient to suicide. Participants spoke about the loss of their patient as a loss of a human being, one with unique qualities. Furthermore, this was a person that participants had often built a relationship with, as articulated by this participant:

I was really disturbed by the loss. That was my first. Just the loss of like a person who I cared about. And a person with whom I had a relationship. So that was first.

Shock

Twelve participants described shock upon hearing the news that a patient had died by suicide. Manifestations of shock differed among participants; some cried, while others felt “numb.”

Even those participants who felt that a particular patient was at “high risk” of suicide, still described a sense of surprise and sometimes shock upon actually hearing the news. This dialectic is described by one of the participants in the following way:

[She was] someone who had a high risk, but obviously they weren’t high risk enough that you were like certifying them or anything. But you know, I was surprised that she did it, but I also wasn’t.

Anxiety

Twelve participants experienced anxiety, often in multiple domains after the patient's death. Anxiety-inducing domains included (a) fear of future patient suicides, (b) anxiety about speaking to patient families, and (c) anxiety about anticipated incident reviews and possible medico-legal repercussions. Highlighting the fear around future patient suicides, one participant articulated,

Well, number one I think I have a sinking feeling anytime now someone doesn’t come back from pass as expected.

Another participant captured the anxiety around speaking with families by explaining:

The biggest stressor at the time was meeting with the family and not knowing what to expect with them.

Many participants explained that they had not received any type of training about speaking to families after a patient's suicide. This exacerbated a sense of being unequipped to be meeting with and supporting families.

Guilt and Shame

For 10 participants, feelings of guilt and shame were prominent after losing a patient to suicide. Cognitions that precipitated these emotions included “I missed something” or “I did something wrong.” One of the participants captured this in the following statement:

I felt like, you know, in a way, like maybe I made a mistake. And like, I was the reason that they died.

Another participant explained:

There was this feeling that like I was close to helping him but couldn’t quite get there, and maybe if I would have tried a little bit harder to engage him…

For some of these 10 participants, there was a desire to protect themselves from embarrassment by keeping the event hidden from their work colleagues. A participant explained:

I was almost embarrassed for both of them [referring to two patient suicides]. I was embarrassed of what my secretary will think of me.

Mediators of Emotional Responses

While there were certain overarching emotional experiences as described above, all psychiatrists did not have the same responses to patient suicide, and some psychiatrists had varying reactions to different patient deaths. Our data indicated that there were key factors that moderated emotional responses to patient suicide. These can broadly be divided into patient factors, relational factors, and physician factors.

Patient Factors

Perceived Predictability of Suicide

A recurrent theme was the idea that the perceived predictability of patient suicide impacted how these psychiatrists responded to the event – 12 participants spoke to this connection. There were some patients who were deemed to be “low risk” or seemed to be improving before they suddenly died by suicide. Participants noted that these losses generated (a) significant feelings of shock and (b) guilt and doubt regarding one's own professional abilities. A participant captured these sentiments in the following quote:

He had come into hospital because he was feeling suicidal and depressed, but he said that resolved completely[…]. So I remember, I went on vacation. And when I came back I discovered that he had died […] My emotional reaction really was shock. And feeling that I had missed something.

Similarly, other participants tried to make sense of their experiences, but doing so was more difficult when psychiatrists felt there was no coherence to their story or their experience.

I find it disconcerting that somebody with a history of GAD, and no other major issues. No substances, no nothing, no trauma… Becomes depressed in the post-partum period and is dead seven months later. Like to me […] to me that is so disconcerting.

Reactions from Patient's Family Members

The patient's family and their reactions also mitigated the emotional responses of psychiatrists. Psychiatrists who had the opportunity to share grief, to attend funerals or memorials, seemed to benefit from these experiences, while anger or blame from the family, contributed to the overall distress experienced by psychiatrists after patient suicide.

So that was the discussion that had happened with that mom. And we actually, we cried and cried over this kid for like 2 1/2 hours, it was very, very, very helpful.

Relational Factors

Patient–Physician Relationship

Some participants had known the patient for many years and had built a long-standing relationship with them. For others, while the relationship may have been short, it had been rich and meaningful, particularly because the clinician knew the patient well. The closeness of the relationship impacted the grief experienced by the participants. All 15 participants who had described strong feelings of grief described detailed knowledge of the patient or a therapeutic relationship that had spanned a long period of time.

A participant who was a supervisor explained: “We had discussed him rather extensively, and we knew a lot about his life […] so you know, we did know him quite well, and in a certain way. So we were both very sad, and very shocked.”

In contrast, participants who had more limited and brief interactions with the patient (e.g., seeing them once in the emergency department) were less likely to describe grief, though they were still vulnerable to other emotions such as shock, guilt or anxiety.

Physician Factors

Fourteen participants spoke about various aspects of their own lives and experiences that impacted their experience of patient suicide.

Prior Experience with Patient Suicide

A prominent factor mediating a participant's reaction to a patient's suicide was the psychiatrist's previous experiences. Those who had prior similar experiences felt that the intensity of shock seemed lesser for subsequent suicides. In addition to decreased shock, 3 participants spoke also about shifting philosophies on suicide through their experiences, and subsequently, less attribution of the blame on themselves after subsequent suicides.

Stressors in Personal Life

Some physicians had stressors ongoing in their personal and professional lives during the time they experienced this patient’s suicide. Stressful circumstances in other domains of life could make it more challenging to cope with patient suicide as evidenced by the following quote:

I had no chance to even process what happened with [name of patient], because of what was going on with my [family member].

Institutional Responses

Responses by the participants’ departments or hospitals were important in how the experience of losing a patient to suicide was processed by the psychiatrists.

Thirteen participants endorsed distress or discomfort around the way their institutions responded to at least one of the patient suicides that they had experienced. The most common reason that was cited for this distress was the perception of being unfairly blamed or scrutinized. Encounters that were experienced as guilt-inducing were the most difficult. This was captured by one participant who stated:

She was on her computer, kind of not making eye contact, and just asking me a lot of questions that just felt like, like I was on trial.

Another common experience was a sense of uncertainty around institutional processes. Participants felt that there was a lack of clarity and transparent communication from their institution, which left them unsure about how to proceed or what to expect after a patient’s suicide had occurred.

Thirteen participants were able to identify positive aspects of their institution's response to a patient's suicide. Positive responses that were highlighted by participants included (a) safe spaces for debriefing that were distinct from formal incident reviews, (b) emotional support from chiefs of the departments or other authority figures, and (c) review processes that were not experienced as unduly critical. For example, the following participant captured this in the following excerpt:

I’ve always found them [quality control meetings] to be informative, very helpful and very supportive […] There are no accusations or blame or holding of accountability. And an emphasis, as always, on what can we learn, what can we do different, going forward.

When asked about how to improve institutional responses to patient suicide, 5 participants highlighted the need for longitudinal support, rather than one-time events. This is captured by a participant who stated,

I don't think everything that stems from a finished suicide can be extinguished by one three-hour meeting. I don't think that's possible.

Non-Institutional Sources of Support

Support from peers and mentors was identified as the most helpful type of support, with 12 participants expressing positive experiences. When asked about what was most helpful about peer support, one participant explained:

They empathized. [Colleague #5] spoke of her own experiences as well […] I also spoke with other psychiatrists here about their experiences. That was helpful.

While the participants’ family members offered emotional support, participants expressed that these individuals could not relate to the experience of a patient dying by suicide, and therefore the support that they could offer was limited.

Impact on Practice

Thirteen participants described a change in their practice after at least one of the patient suicides that they had experienced. While some considered changing or leaving their practice, none of the participants changed the setting of their practice as a direct consequence of patient suicide.

The most common change was increased caution in the participants’ practices, particularly for inpatient psychiatrists as they made decisions about passes (time outside of a secure patient unit) and discharges. For some, this was a temporary and unwelcome change, often driven by anxiety. This was described by the following participant:

I think I was more hesitant to discharge people who were suicidal for some time after that and, you know, that's like 60% of my patients […] I don't think it was positive.

Other participants described a thoughtful and calculated shift in practice that was described as an overall improvement. Participants described more detailed documentation. Others engaged in continuing education about conducting and documenting safety assessments. One participant captured this in the following statement:

I feel like I’m a better clinician at the end of the day. I feel like I do a better safety assessment. So in a way, her legacy, in my head, is that I’m more careful […] I’m going through every possible factor to make sure that I’m doing the right decision. And that's a good thing.

Discussion

This study indicates that patient suicide is often associated with grief, shock, anxiety and guilt; emotions which are mediated by physician, patient, relational and institutional factors and have important ramifications on psychiatrists’ well-being and clinical practice.

While previous studies have found feelings of shock and distress to be prevalent, less attention has been paid to grief or sadness.3,8 However, one of the few existing qualitative studies on this topic highlighted “unburdening grief” as the central theme of their analysis which is in line with our findings. 10 The nature of the physician–patient relationship contributed to the nature and intensity of grief experienced by the participants in our study. A close therapeutic relationship with a patient was also identified as an important factor influencing the intensity of reactions in previous studies.7,19,20

In addition to the patient–physician relationship, a major recurrent theme was the effect of perceived predictability of suicide on psychiatrists’ experiences. This finding highlights a critical and controversial tension within psychiatry. While attempts have been made to develop predictive tools, none have been demonstrated to accurately predict suicide.21–23 Even risk stratification, considered to be a more realistic approach than a prediction has been considered to have limited utility, with data indicating that over 50% of patients who die by suicide would have been classified as “low risk.” 24 Despite this broader context, the participants in this study struggled with the idea that they had not predicted risk for their patients. While our study did not point to a definitive reason for this phenomenon, it is likely that hindsight bias played a role. Hindsight bias is defined as the tendency of individuals who have knowledge of an outcome to exaggerate their ability to predict that outcome; this bias has been studied in other medical specialties as well. 25

In our study, feelings of anxiety were heightened by a sense of uncertainty about tasks and obligations to be completed after a patient suicide. Participants were unsure about what to expect from their own institutions about procedural elements after a patient suicide. While postvention strategies have been recommended for trainees, 26 to our knowledge, no specific guidelines exist for postvention strategies specifically for psychiatrists.

Our study highlights that psychiatrists experience patient suicide events as longitudinal processes, often spanning the course of months and sometimes, years. While support and resources are typically front-loaded, our findings suggest that psychiatrists may benefit from longitudinal support, whether it is sought formally through work or informally through mentors and colleagues.

Support from colleagues or informal mentors was considered to be very helpful within our sample, a finding that is supported by the existing literature. 21 Participants reported that a sense of validation and solidarity was key in alleviating distress. Debriefs and incident reviews have the potential to be helpful tools for processing patient suicide, but carry a risk of heightening distress and anxiety for psychiatrists. 27 Based on the experiences of the participants in this study, separating debriefs from formal incident reviews can be helpful in creating a distinct space for emotional processing and team support. These and additional recommendations based on our findings are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Considerations for Institutions Supporting Psychiatrists.

|

Limitations and Future Directions

There are some limitations to consider. Eighteen psychiatrists were interviewed for this study, and while this is robust sample size for a qualitative study, it limits the generalizability of the findings. The majority of the participants in this study practised within academic institutions, and their experiences likely differ from those who work within the community and private practices or rural settings, which are often under-resourced and further research is needed to evaluate the experiences of psychiatrists working in these areas. The role of psychiatrists’ race and ethnicity was not formally explored in this study and could be an important area for further study.

Conclusion

The experience of patient death by suicide represents a major event in the career trajectory of most psychiatrists. Our study indicates that this event is commonly associated with grief, shock, anxiety and guilt, which are mediated by individual and organizational factors. The support received by psychiatrists plays an important role in processing these difficult emotions. Our results and the associated recommendations should be considered and utilized when a psychiatrist experiences a patient death by suicide.

Appendix A

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)*

http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/srqr/

| Title and abstract | Page |

|---|---|

| Title - Concise description of the nature and topic of the study Identifying the study as qualitative or indicating the approach (e.g., ethnography, grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g., interview, focus group) is recommended | Page 1 |

| Abstract - Summary of key elements of the study using the abstract format of the intended publication; typically includes background, purpose, methods, results, and conclusions | Page 1 |

| Introduction | |

| Problem formulation - Description and significance of the problem/phenomenon studied; review of relevant theory and empirical work; problem statement | Page 1 |

| Purpose or research question - Purpose of the study and specific objectives or questions | Page 2 |

| Methods | |

| Qualitative approach and research paradigm - Qualitative approach (e.g., ethnography, grounded theory, case study, phenomenology, narrative research) and guiding theory if appropriate; identifying the research paradigm (e.g., postpositivist, constructivist/ interpretivist) is also recommended; rationale** | Page 2 |

| Researcher characteristics and reflexivity – Researchers’ characteristics that may influence the research, including personal attributes, qualifications/experience, relationship with participants, assumptions, and/or presuppositions; potential or actual interaction between researchers’ characteristics and the research questions, approach, methods, results, and/or transferability | Page 3 |

| Context - Setting/site and salient contextual factors; rationale** | Page 2 |

| Sampling strategy - How and why research participants, documents, or events were selected; criteria for deciding when no further sampling was necessary (e.g., sampling saturation); rationale** | Page 2 |

| Ethical issues pertaining to human subjects - Documentation of approval by an appropriate ethics review board and participant consent, or explanation for lack thereof; other confidentiality and data security issues | Page 2 |

| Data collection methods - Types of data collected; details of data collection procedures including (as appropriate) start and stop dates of data collection and analysis, iterative process, triangulation of sources/methods, and modification of procedures in response to evolving study findings; rationale** | Page 2 |

| Data collection instruments and technologies - Description of instruments (e.g., interview guides, questionnaires) and devices (e.g., audio recorders) used for data collection; if/how the instrument(s) changed over the course of the study | Page 2, Appendix B and C |

| Units of study - Number and relevant characteristics of participants, documents, or events included in the study; level of participation (could be reported in results) | Page 4 |

| Data processing - Methods for processing data prior to and during analysis, including transcription, data entry, data management and security, verification of data integrity, data coding, and anonymization/de-identification of excerpts | Page 3 |

| Data analysis - Process by which inferences, themes, etc., were identified and developed, including the researchers involved in data analysis; usually references a specific paradigm or approach; rationale** | Page 3 |

| Techniques to enhance trustworthiness - Techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis (e.g., member checking, audit trail, triangulation); rationale** | Page 3 |

| Results/findings | |

| Synthesis and interpretation - Main findings (e.g., interpretations, inferences, and themes); might include development of a theory or model or integration with prior research or theory | Pages 4–11 |

| Links to empirical data - Evidence (e.g., quotes, field notes, text excerpts, photographs) to substantiate analytic findings | Pages 4–11 |

| Discussion | |

| Integration with prior work, implications, transferability, and contribution(s) to the field – Short summary of main findings; explanation of how findings and conclusions connect to, support, elaborate on, or challenge conclusions of earlier scholarship; discussion of the scope of application/generalizability; identification of unique contribution(s) to scholarship in a discipline or field | Pages 11–12 |

| Limitations - Trustworthiness and limitations of findings | Page 13 |

| Other | |

| Conflicts of interest - Potential sources of influence or perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions; how these were managed | Page 13 |

| Funding - Sources of funding and other support; role of funders in data collection, interpretation, and reporting | Page 1 |

*The authors created the SRQR by searching the literature to identify guidelines, reporting standards, and critical appraisal criteria for qualitative research; reviewing the reference lists of retrieved sources, and contacting experts to gain feedback. The SRQR aims to improve the transparency of all aspects of qualitative research by providing clear SRQR.

**The rationale should briefly discuss the justification for choosing that theory, approach, method, or technique rather than other options available, the assumptions and limitations implicit in those choices, and how those choices influence study conclusions and transferability. As appropriate, the rationale for several items might be discussed together.

Appendixes B and C

Qualitative Interview Guide

1. Venue: Wherever it is convenient for the participant and allows sufficient privacy. The location and time will be discussed prior to the meeting.

2. Duration: As long as it takes for the participants to complete their stories, although we will try not to go over one hour. If the participant is tired, let him or her take a break. Use your discretion if it is better to go back a second time to continue the interview.

- 3. Procedures:

- A. SET UP

- i. Introduce yourself and the purpose of the interview, e.g., “I am a researcher working on a study of psychiatrists who have experienced a patient suicide in their practice. The purpose of this study is to better understand these experiences and their impact on the clinical practice of psychiatrists.”

- ii. Explain the key content in the consent form (e.g., confidentiality and anonymity, the participant's right to withdraw and to delete data).

- iii. Explain the need for audio recording and obtain approval from the participant. [Remember to bring your recorder and to check it for proper functioning, including sufficient battery life, and memory space for recording]

- iv. Obtain written consent.

- 4. Open exploration

- Start the conversation with a brief prompt, e.g., you may repeat the purpose of the research and invite the participant to share his/her experience, the following are examples of what you may want to say to the participant:

- Thank you for giving us the time to do this interview with you. The main purpose of this interview is to understand your experiences with patient suicide. We are most interested in your personal experience.

- You can start with whatever you want to talk about first (if participants asked what they should start with).

- The main purpose of this part of the interview is to allow the participants to express themselves as freely as possible, this can be achieved by keeping in mind that:

- The participant decides what is important to him/her, so let them talk about whatever they want to as much as possible. That means we DO NOT control the agenda rigidly, but try to allow maximum narrative space. You may also want to make sure that you do not interrupt the participant or cut her/him off.

- Each individual has his/her own idea of what is relevant to the research question. You should let them talk even though you may find what he/she says is irrelevant. You may, however, repeat the research question at times to remind.

- Respect the participant's language by using their expression and their wordings as closely as possible, this will avoid unnecessary (mis)interpretation and narrative conditioning on our part.

- Use more prompts and invitations, and use less questions; e.g., invite them to elaborate on or explain about, or give examples for a topic or an experience that they have mentioned. A question-and-answer format tends to put the participant in a passive mode, and severely compromises the opportunity for the participant to volunteer information which is not on your list of questions, therefore defeating the very purpose of ethnographic or discovery-oriented interviewing. If you need to ask questions, ask open-ended and not closed-ended questions. Ask specific questions only when you have collected enough information from a topic and need to know the specific details.

- Summarize what the participant has said would let him/her know that you’ve been listening, and help to build a good rapport. This is also helpful when you want to shift the conversation to another topic - make a summary first and smoothly change the topic. Try to be brief with summaries, for long summaries might turn people off.

- The purpose of this interview is to explore and discover, NOT to solve problems, provide therapy/counselling, or offer help.

- Pay attention to “free information” (content not required by your question or request, given to you freely): The participant offers as he/she responds to your prompts and questions, these are often things that the participant wants to talk more about

- Please try to jot down detailed notes during the interview, this will help you to keep track of what has been said and to make a summary. Please also note down your impressions, and the participant's non-verbal behaviors whenever possible. These notes can be especially valuable in the unlikely event of recording failure.

- When you think the open exploration part has been completed, try to summarize the main points of the conversation and ask the participant if he/she has anything more to add. If not, thank him/her for the sharing. Then prepare them for the structured exploration part by saying something like, “In the remaining time, I am going to ask you some further questions.”

- 5. Structured Inquiry

- The purpose of the structured inquiry is to focus on specific areas or issues we are interested in, but have not been addressed by the participant in the Open Exploration section. It is hoped that by this time, you would have established a good relationship with the participant and he/she might be more ready to talk about these topics

- Before we ask the questions, note if any of them had already been answered during the Open Exploration. Ask only those that have not been addressed. Asking the question again will make the participant feel that we have not been paying attention and listening carefully.

Topics of Exploration

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself? Your background?

What drew you to psychiatry?

Can you tell me a bit about your career trajectory since the completion of your residency training?

What does your day-to-day clinical practice look like?

Do you have specialized interests in psychiatry?

- How many patient suicides have you experienced during your career, including your years in residency training?

- Which of these experiences had the greatest impact on you?

Can you tell me a bit about your connection with the patient prior to the suicide event?

Can you walk me through the day that you found out about the patient's suicide?

- Can you tell me about the days immediately following the event?

- What did you find most stressful?

- What did you find most helpful?

Are there supports that you wish you had received during this time?

After this event, what was it like for you to see other patients who were experiencing suicidal ideation or behaviours?

Did you implement any changes to your clinical practice after this event? Can you describe these for me?

Was there any change in the type of patients that you saw after this event?

What impact do you think this experience had on you in the long term? Did this event impact your career decisions moving forward?

Ways in which to ask follow-up questions about sensitizing topics (probes and clarification)

Can you tell me more about that (person, event)?

Can you give me a specific example?

Can you explain your answer?

In what way?

How did you understand that?

What does that mean to you?

Wrap up questions

Do you have anything to add?

Is there anything I should have asked?

How did the interview feel for you?

Is there anything that surprised you?

How are you feeling now?

Appendix D. Coding Tree

| Code categories |

|---|

| Emotional responses |

| Experiences of providing support |

| Experiences of receiving support |

| Institutional responses |

| Negative institutional responses |

| Positive institutional support |

| Suggestions for how to support |

| Impact on professional practice |

| Mediators of emotional responses |

| Circumstances of receiving the news |

| Institutional challenges |

| Patient characteristics |

| Personal factors |

| Relationship with patient |

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Excellence Funds, and awarded through the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto.

ORCID iDs: Zainab Furqan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8172-8367

Rachel Beth Cooper https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5368-8927

Mark Sinyor https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7756-2584

Paul Kurdyak https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8115-7437

Juveria Zaheer https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5071-8078

References

- 1.McDowell AK, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Practical suicide-risk management for the busy primary care physician. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2011 Aug 1; Elsevier; Vol. 86, No. 8, p. 792-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(5):613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander DA, Klein S, Gray NM, Dewar IG, Eagles JM. Suicide by patients: questionnaire study of its effect on consultant psychiatrists. Br Med J. 2000;320(7249):1571-1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erlich MD, Rolin SA, Dixon LB, et al. Why we need to enhance suicide postvention: Evaluating a survey of psychiatrists behaviors after the suicide of a patient. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothes IA, Scheerder G, Van Audenhove C, Henriques MR. Patient suicide: The experience of flemish psychiatrists. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2013;43(4):379-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomyangkoon P, Leenaars A. Impact of death by suicide of patients on Thai psychiatrists. Suicide Life-Threatening Behav. 2008;38:728‐740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulfi A, Castelli Dransart DA, Heeb JL, Gutjahr E. The impact of patient suicide on the professional practice of swiss psychiatrists and psychologists. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(1):13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruskin R, Sakinofsky I, Bagby RM, Dickens S, Sousa G. Impact of patient suicide on psychiatrists and psychiatric trainees. Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28(2):104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knox S, Burkard A, Jackson JA, Schaack AM, Hess SA. Therapists-in-training who experience a client suicide: implications for supervision. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2006;37:547‐555. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talseth AG, Gilje F. Unburdening suffering: responses of psychiatrists to patients’ suicide deaths. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(5):620‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders S, Jacobson J, Ting L. Reactions of mental health social workers following a client suicide completion: a qualitative investigation. OMEGA - J Death Dying. 2005;51(3):197‐216. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darden AJ, Rutter PA. Psychologists’ experiences of grief after client suicide: a qualitative study. OMEGA – J Death Dying. 2011;63(4):317‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christianson CL, Everall RD. Breaking the silence: school counsellors’ experiences of client suicide. Br J Guid Counc. 2009;37(2):157‐168. [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245‐1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (1st ed.). New York:Routledge;1999. 10.4324/9780203793206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etikan I, Alkassim R, Abubakar S. Comparison of snowball sampling and sequential sampling technique. Biom Biostat Int J. 2016;3(1):55.

- 18.Atkinson R. The life story interview. Thousand Oaks: Sage. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaffney P, Russell V, Collins K, et al. Impact of patient suicide on front-line staff in Ireland. Death Stud. 2009;33(7):639-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendin H, Haas AP, Maltsberger JT, Szanto K, Rabinowicz H. Factors contributing to therapists’ distress after the suicide of a patient. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1442‐1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho AO. Suicide: rationality and responsibility for life. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59:141‐147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan MK, Bhatti H, Meader N, et al. Predicting suicide following self-harm: systematic review of risk factors and risk scales . Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(4):277-283. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2016;143(2):187‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Large MM, Ryan CJ, Carter G, Kapur N. Can we usefully stratify patients according to suicide risk? Br J Psychiatry. 2017;359. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.LeBourgeois HW, Pinals DA, Williams V, Appelbaum PS. Hindsight bias among psychiatrists. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(1):67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qayyum Z, Luff D, Van Schalkwyk GI, AhnAllen CG. Recommendations for effectively supporting psychiatry trainees following a patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45:301‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landers A, O’Brien S, Phelan D. Impact of patient suicide on consultant psychiatrists in Ireland. The Psychiatrist. 2010;34(4):136-140.