Abstract

We examined associations of an AD genetic risk score (AD-GRS) and midlife cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes in 1,252 middle-aged participants (311 with brain MRI). A higher AD-GRS based on 25 previously identified loci (excluding APOE) was associated with worse Montreal Cognitive Assessment (−0.14 SD[95% CI:−0.26,−0.02]), older machine learning predicted brain age (2.35 years[95%CI:0.01,4.69]), and white matter hyperintensity volume (0.35 SD [95% CI:0.00,0.71), but not with a composite cognitive outcome, total brain, or hippocampal volume. APOE ε4 allele was not associated with any outcomes. AD risk genes beyond APOE may contribute to subclinical differences in cognition and brain health in midlife.

Summary for Social Media If Published

1. If you and/or a co-author has a Twitter handle that you would like to be tagged, please enter it here. (format: @AUTHORSHANDLE).

@WillaBrenowitz @KristineYaffe

2. What is the current knowledge on the topic?

Genetic risk scores for Alzheimer’s disease (AD-GRS) predict increased risk of dementia, faster rates of cognitive decline, and brain atrophy in late-life. Little is known about the associations in midlife, although accumulating evidence suggest midlife may be a critical window for dementia prevention.

3. What question did this study address?

This study assessed whether an AD-GRS is associated with cognitive outcomes or brain atrophy among a cohort of middled age white adults.

4. What does this study add to our knowledge?

Middle aged participants with a higher AD-GRS, not including APOE, was associated with a lower overall cognition, worse age-related brain atrophy, and higher white matter intensity volume compared to participants with a lower AD-GRS, but there were no associations with the APOE ε4 allele. This suggests there are subtle cognitive and brain changes in midlife associated with AD genetic risk beyond the effects of APOE.

5. How might this potentially impact on the practice of neurology?

AD-GRS may help screen for individuals at high risk of developing dementia. Future work is needed to confirm our results, but AD-GRS may help identify individuals at higher risk of dementia even in middle age, which could inform the timing of screening and intervention strategies.

Introduction

Genetic risk scores for AD are associated with cognitive and neuroimaging outcomes in late-life,1–3 and could help predict preclinical AD.4 Few studies have examined associations in midlife. Understanding when AD genes begin to affect cognition or brain structure has implications for when treatment strategies would be most effective.

Midlife is increasingly seen as a window of opportunity for early detection and prevention,5 yet few studies have examined AD genetic risk and midlife cognitive or neuroimaging outcomes. Recent work in the large UK Biobank suggested the association between higher AD genetic risk and worse cognition may begin in midlife.6 In a middle-age cohort, several individual AD-risk loci were nominally associated with poor cognition.7 However, another study found no associations between AD genetic risk or APOE genotype and midlife cognition.8 Studies in young adults suggest high AD genes may confer early susceptibility to reduced hippocampal volume,1,9 but none have focused on midlife.

We investigated the association of an AD genetic risk score (AD-GRS) with global cognition and brain MRI outcomes in middle aged adults in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA). To understand associations with AD genetic loci beyond APOE genotype, we focus on an AD genetic risk score without APOE, and APOE genotype separately.

Methods

Study Population

CARDIA is an ongoing prospective cohort of 5,115 white and Black adults ages 18–30 recruited in 1985–86 from four cities who have completed up to eight follow-up examinations spanning 30 years.10 We focus on Year 30 visit for analyses, as participants were middle-aged, underwent cognitive testing, and a subset had brain MRI. Year 30 MRI participants were enrolled from those who had received an MRI in Year 25, which is described elsewhere in detail.11 Those with contraindications (e.g., metal implants or body size too large for scanner) were excluded. Year 25 individuals who declined Year 30 MRI were replaced with random samples recruited by each site individually up to the total number of MRIs in Year 25. Recent studies12 and our preliminary data in CARDIA suggest that the variants used in our genetic risk score are not generalizable Black participants, so we restricted the current study to white participants with European genetic ancestry, complete genetic data, and at least one cognitive measure (n=1,252, n=311 with brain MRI). At each visit, participants provided written informed consent, and study protocols were reviewed by institutional review boards from each study site, the CARDIA Coordinating Center at the University of Alabama, Birmingham and the University of California, San Francisco.

Genotyping and Genetic Risk Score

CARDIA samples were genotyped with the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Santa Clara, CA, USA), quality controlled, and imputed to 1000 Genomes version 3. The AD genetic risk score (AD-GRS) was calculated based on summary statistics of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) associated with AD. Specifically, we calculated the AD-GRS based on 25 SNPs, each corresponding to a different loci (Table 1) not including the APOE region, identified as genome-wide significant in the 2019 International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project meta-analyzed genome-wide association study on late-onset AD in Europeans.13 This approach is similar to prior studies1,2,6 and follows recommendations from prior work that found genetic architecture of late-onset AD is oligogenic (e.g. due to a small set of genes),14 The AD-GRS was calculated in PLINK as a weighted sum of an individual’s AD risk allele count; with weights as the β coefficient for AD for each SNP. APOE ε4 allele (0, 1+) was derived from APOE phenotype assays. Principal components (PCs) related to genetic population stratification were also calculated.

Table 1.

SNPs and log odds ratio estimates (weights) for the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score (AD-GRS)

| Marker Name | Chromosome | Closest gene | Effect Allele | Effect Estimate | Odds Ratio for AD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs4844610 | 1 | CR1 | A | 0.157 | 1.17 |

| rs6733839 | 2 | BIN1 | T | 0.182 | 1.2 |

| rs10933431 | 2 | INPP5D | G | −0.094 | 0.91 |

| rs9271058 | 6 | HLA -DRB1 | A | 0.095 | 1.1 |

| rs75932628 | 6 | TREM2 | T | 0.732 | 2.08 |

| rs9473117 | 6 | CD2AP | C | 0.086 | 1.09 |

| rs114812713 | 6 | OARD1 | C | 0.278 | 1.32 |

| rs12539172 | 7 | NYAP1 | T | −0.083 | 0.92 |

| rs10808026 | 7 | EPHA1 | A | −0.105 | 0.9 |

| rs73223431 | 8 | PTK2B | T | 0.095 | 1.1 |

| rs9331896 | 8 | CLU | C | −0.128 | 0.88 |

| rs7920721 | 10 | ECHDC3 | G | 0.077 | 1.08 |

| rs3740688 | 11 | SPI1 | G | −0.083 | 0.92 |

| rs7933202 | 11 | MS4A2 | C | −0.117 | 0.89 |

| rs3851179 | 11 | PICALM | T | −0.128 | 0.88 |

| rs11218343 | 11 | SORL1 | C | −0.223 | 0.8 |

| rs17125924 | 14 | FERMT2 | G | 0.131 | 1.14 |

| rs12881735 | 14 | SLC24A4 | C | −0.083 | 0.92 |

| rs593742 | 15 | ADAM10 | G | −0.073 | 0.93 |

| rs7185636 | 16 | IQCK | C | −0.083 | 0.92 |

| rs62039712 | 16 | WWOX | A | 0.148 | 1.16 |

| rs138190086 | 17 | ACE | A | 0.262 | 1.3 |

| rs3752246 | 19 | ABCA7 | G | 0.140 | 1.15 |

| rs6024870 | 20 | CASS4 | A | −0.128 | 0.88 |

| rs2830500 | 21 | ADAMTS1 | A | −0.073 | 0.93 |

Global Cognition

A standardized cognitive battery was administered in Year 30.15 Tests included: the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, the Rey Auditory-Verbal Learning delayed test, the Stroop Interference Test (scores were inversed for analysis); Category and Letter Fluency Tests; and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) a measure of global cognition. Our primary measures were the MoCA and a composite cognitive score, which was a weighted average of each test standardized.

MRI and Data Processing

Brain MRI at Year 30 were collected with 3-T MR scanners, images were processed using standardized QC measures and an automated pipeline,16 regional brain volumes were derived from T1 and T2 sequences.11 A measure of predicted “brain age” was separately derived from a machine learning approach using high-dimensional classification developed based on patterns from older samples and applied to CARDIA.17 The brain age index differentiates individuals exhibiting “advanced brain aging” from those with normal brain aging and captures a more complex spectrum of structural changes than region-specific volumes. Total brain volume, total hippocampal volume, and total white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume were secondary measures.

Statistical Analysis

Multiple linear regressions evaluated the association between the AD-GRS without APOE and each measure of global cognition (MoCA and composite score) and MRI outcomes (for those with brain MRI), with adjustment for age at year 30 visit, sex, education, and 10 principal components. Models for MRI outcomes additionally adjusted for intra-cranial volume, and MRI collection center. We reran analyses with APOE ε4 allele as the primary predictor and examined interactions between the AD-GRS and APOE ε4 allele. Analyses were conducted in R (version 3.3.2), tests were 2-sided alpha=0.05.

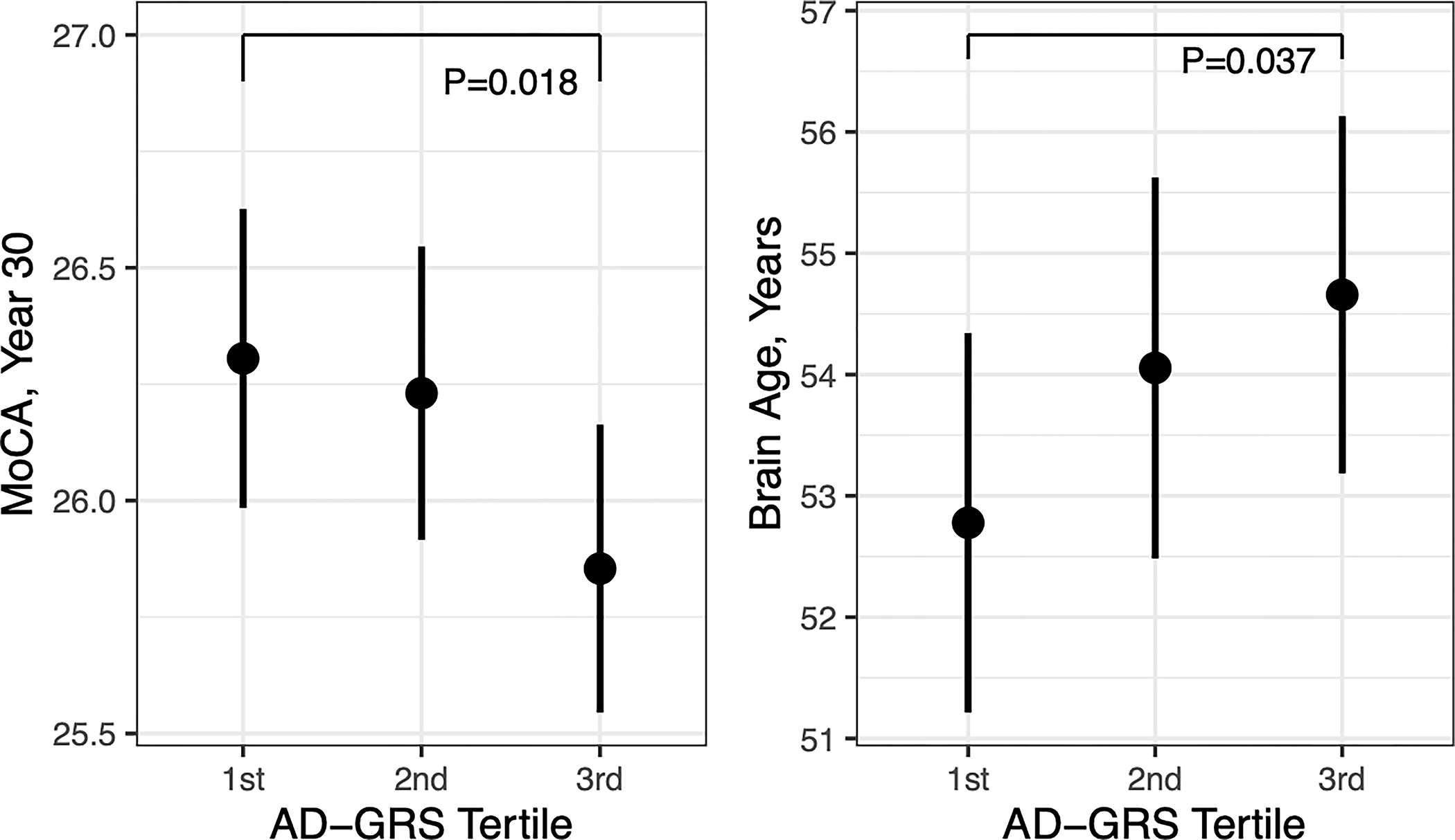

Results

Participants mean age was 55.8 (standard deviation (SD): 3.3), 54.3% were female; 24.4% had at least one APOE ε4 allele; and the mean AD-GRS without APOE was −0.18 (SD: 0.31; range: −1.23 to 1.06), corresponding to log odds of AD). In adjusted modes, the continuous AD-GRS without APOE was associated with a 0.14 standard deviation (SD) lower MoCA scores (95% CI:−0.26, −0.02) (Table 2) and a graded trend by tertile of the AD-GRS (Figure 1). There was no association with the composite cognitive score, although the estimate was in the same direction. Among 311 participants with MRI; higher AD-GRS without APOE was associated with older predicted brain age (Table 2) and demonstrated a graded trend by tertile of the AD-GRS (Figure 1). The AD-GRS without APOE was also associated with higher WMH volume (0.35 SD higher [95% CI:0.00, 0.71]), but not total brain volume nor hippocampal volume. Participants with MRI were similar to Year 30 participants without MRI in terms of demographic, clinical, and genetic characteristics AD-GRS (mean: −0.16, SD: 0.31); with the exception of having a lower prevalence of obesity and diabetes (p<0.05). APOE ε4 allele was not associated with any outcomes (Table 2), there were no interaction between AD-GRS and APOE ε4 allele (P<0.05); excluding participants with APOE ε4 alleles did not substantively change estimates of the AD-GRS with MoCA, predicted brain age, or WMH but reduced precision (data not shown).

Table 2.

Association of AD Genetic Risk Score (GRS) and APOE ε4 allele with midlife cognition and brain MRI outcomes

| Outcome (in SD unless noted otherwise) | AD-GRS without APOE (continuous score) | APOE ε4 allele (any vs none) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Cognition * | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) |

| MoCA | −0.14 (−0.26, −0.02) | −0.05 (−0.14, 0.05) |

| Composite Score | −0.03 (−0.10, 0.05) | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) |

| Brain Health** | ||

| Brain Age, years | 2.35 (0.01, 4.69) | 0.44 (−1.28, 2.17) |

| Total Brain Volume | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.02) | 0.05 (−0.04, 0.14) |

| Hippocampal Volume | −0.24 (−0.54, 0.06) | 0.18 (−0.04, 0.39) |

| White Matter Hyperintensity Volume | 0.35 (0.00, 0.71) | 0.07 (−0.19, 0.32) |

MoCA; Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SD: standard deviation

Models adjusted for age, sex, education, 10 principal components

Models additionally adjusted for intracranial volume and MRI assessment center

Figure 1.

Association of Alzheimer’s Disease Genetic Risk Score (AD-GRS) tertile with midlife Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score and predicted brain age based on structural MRI.

Discussion

We examined whether AD genetic risk associated with cognition and structural MRI as assessed among white middle-aged adults. Higher AD-GRS without APOE was associated with a lower MoCA score, worse age-related brain atrophy, and higher WMH volume compared to lower AD-GRS. These findings are important given that the mean age of CARDIA participants was 55 and the sample was relatively small. However, significant associations with other cognitive tests and brain regions were not found. We also did not find associations with APOE genotype. This suggests cognitive and brain changes associated with AD genetic risk in midlife are subtle.

Genetic risk scores are popular tools, but previous studies focus on late-life outcomes,1–3 our study expands research on midlife outcomes. A prior study in middle-aged adults found several individual AD-risk loci (including APOE ε4 allele) were associated with poor cognition, but found no associations with a polygenic risk score.7 We found associations in an AD-GRS without APOE, but no effects for APOE alone, suggesting a contribution of multiple SNPs beyond APOE. The lack of association with APOE genotype in our study, is surprising but in line with another study in middle-aged adults,8 and the APOE ε4 allele has also been associated with better cognitive performance in early life.18 It may not be until late life (e.g. 65+) that effects of the APOE ε4 allele on cognition develop.

We examined brain health associated with AD genetic risk focusing on a machine learning derived brain aging index.17 Our lack of findings with total brain volume and hippocampal volume, suggest that participants in this analysis were too young for substantial AD neurodegeneration. However, the AD-GRS without APOE was associated with older predicted brain age and a higher volume of WMH. In an a prior study an AD-GRS (based on fewer genetic loci) was not associated with predicted brain age but was associated with AD-atrophy in older ages.19 The brain aging index and WMH may be more sensitive to early neurodegeneration. WMH are more strongly associated with preclinical AD than other imaging markers including hippocampal volume.20

It is unclear whether associations in our study represent early AD-related changes, the effects of other shared pathways, or lifelong susceptibility. Studies in younger adults suggest that high AD genetic risk may confer early susceptibility to lower hippocampal volumes,1,9 but these results do not match our findings. Our results may represent early pathophysiologic changes associated with AD genetic pathways that increase risk for dementia. Given our small sample size we did not further examine specific genes, however, there may be differences in effect on cognitive or brain outcomes by individual genes, gene-interactions, or implicated genetic pathways (e.g. innate immunity or lipid metabolism). Future work in larger samples involving longitudinal measures of AD biomarkers and in-depth genomic analyses may help elucidate neurophysiologic changes in midlife that promote AD.

This study has several limitations including a small sample and cross-sectional assessments of cognition and MRIs which limits power to detect associations. SNPs used in the GRS represent known and candidate risk loci for AD;13 however, there may remain inaccuracy in our AD-GRS and not all risk loci are well-established as causal. There are multiple approaches to GRS, including using SNPs from the whole-genome to capture more variance.3 Such approaches could identify different findings, but prior work suggests prediction of AD is maximized when using GRS based on selecting a smaller number of SNPs14 as in our approach. We studied white participants and our findings may not be generalizable to other racial or ethnic groupings. Future work is needed to develop informative AD-GRS for multi-ethnic samples. However, this study has several strengths as well including a population-based sample with genotyping, cognitive assessments, brain MRI, and machine learning derived imaging measures in middle age.

We found that a higher AD genetic risk excluding APOE was associated with detectable but limited cognitive and brain differences in middle-aged white adults. Midlife may be an important window for early identification and intervention to prevent AD. This is preliminary work, and future larger studies are needed to replicate these findings, to extend studies to more diverse aging populations, and to examine associations using longitudinal data.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to all of the CARDIA study participants, clinicians, and staff that made this research possible.

CARDIA is supported by contracts HHSN268201800003I, HHSN268201800004I, HHSN268201800005I, HHSN268201800006I, and HHSN268201800007I from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). CARDIA was also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intra-agency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005). This work was also supported in part by NIH grants K01AG062722, U01AG052409, R35AG071916, 1R01AG080821, P30AG066546, 1U24AG074855, and the San Antonio Medical Foundation grant SAMF – 1000003860.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

WDB, MF, MH, and KY report grant funding from NIH. None of the funding sources had involvement in the conduct of this research or preparation of the manuscript. Unrelated to this current study, KY is a Board Member of Alector.

Data Availability:

CARDIA data is available for approved research projects, see more details at https://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/.

References

- 1.Mormino EC, Sperling RA, Holmes AJ, et al. Polygenic risk of Alzheimer disease is associated with early- and late-life processes. Neurology 2016;87(5):481–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desikan RS, Fan CC, Wang Y, et al. Genetic assessment of age-associated Alzheimer disease risk: Development and validation of a polygenic hazard score. PLOS Medicine 2017;14(3):e1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escott-Price V, Shoai M, Pither R, et al. Polygenic score prediction captures nearly all common genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging 2017;49:214.e7–214.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leonenko G, Sims R, Shoai M, et al. Polygenic risk and hazard scores for Alzheimer’s disease prediction. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2019;6(3):456–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchie K, Ritchie CW, Yaffe K, et al. Is late-onset Alzheimer’s disease really a disease of midlife? Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2015;1(2):122–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman SC, Brenowitz WD, Calmasini C, et al. Association of Genetic Variants Linked to Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease With Cognitive Test Performance by Midlife. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(4):e225491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bressler J, Mosley TH, Penman A, et al. Genetic variants associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease contribute to cognitive change in midlife: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2017;174(3):269–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunce D, Bielak AAM, Anstey KJ, et al. APOE genotype and cognitive change in young, middle-aged, and older adults living in the community. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69(4):379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley SF, Tansey KE, Caseras X, et al. Multimodal Brain Imaging Reveals Structural Differences in Alzheimer’s Disease Polygenic Risk Carriers: A Study in Healthy Young Adults. Biol Psychiatry 2017;81(2):154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol 1988;41(11):1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Launer LJ, Lewis CE, Schreiner PJ, et al. Vascular factors and multiple measures of early brain health: CARDIA brain MRI study. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0122138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkle BW, Schmidt M, Klein H-U, et al. Novel Alzheimer Disease Risk Loci and Pathways in African American Individuals Using the African Genome Resources Panel: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology 2021;78(1):102–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet 2019;51(3):414–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Q, Sidorenko J, Couvy-Duchesne B, et al. Risk prediction of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease implies an oligogenic architecture. Nat Commun 2020;11(1):4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Launer LJ, Miller ME, Williamson JD, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering on brain structure and function in people with type 2 diabetes (ACCORD MIND): a randomised open-label substudy. Lancet Neurol 2011;10(11):969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldszal AF, Davatzikos C, Pham DL, et al. An image-processing system for qualitative and quantitative volumetric analysis of brain images. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1998;22(5):827–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Habes M, Pomponio R, Shou H, et al. The Brain Chart of Aging: Machine-learning analytics reveals links between brain aging, white matter disease, amyloid burden, and cognition in the iSTAGING consortium of 10,216 harmonized MR scans. Alzheimers Dement 2021;17(1):89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mondadori CRA, de Quervain DJ-F, Buchmann A, et al. Better memory and neural efficiency in young apolipoprotein E epsilon4 carriers. Cereb Cortex 2007;17(8):1934–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habes M, Janowitz D, Erus G, et al. Advanced brain aging: relationship with epidemiologic and genetic risk factors, and overlap with Alzheimer disease atrophy patterns. Transl Psychiatry 2016;6(4):e775–e775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandel BM, Avants BB, Gee JC, et al. White matter hyperintensities are more highly associated with preclinical Alzheimer’s disease than imaging and cognitive markers of neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2016;4:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

CARDIA data is available for approved research projects, see more details at https://www.cardia.dopm.uab.edu/.