Abstract

Line shapes of anionic fluorescein fluorescence in suspensions of polystyrene nanoparticles (PSNP), anionic and cationic micelles, lipid vesicles, and of laurdan in lipid vesicles were investigated. Computed second harmonic of measured spectra indicated three lines for fluorescein and two for laurdan. Accordingly, fluorescein spectra were fit to three Gaussians and laurdan spectra to two lognormal distributions. Resolved line parameters were examined against particle concentration. Scattering, although wavelength dependent, affected intensity but not line shape. Inner filter effects of scattering on line shape are insignificant because multiple scattering, redirection of scattered photons into the detector, and inclusion of scattered photons in collection and detection minimize wavelength dependent effects. Dominant effects on line width and peak positions are due to physicochemical effects of dye-particle-solvent interactions rather than scattering. Fluorescein does not interact with anionic micelles and lipid vesicles, but remains in the aqueous phase, and responds to pH increase induced by these additives. Blue shift in peak position, decrease in line width, and increase in emission intensity in these systems are like those in NaOH solutions. Fluorescein does interact with cationic micelles and hydrophobic PSNP, and its emission is red shifted. Laurdan in lipid vesicles senses interface polarity. Blue shift and decrease in line width of its emission line indicate decreasing polarity with lipid concentration. Scattering, as well as interactions affect emission intensity. Physicochemical effects distort line shape and modify intrinsic spectra. Line shape changes are better markers than intensity to investigate interactions and reactions.

Keywords: Fluorescence, line shape, scattering, physicochemical, inner filter effects, line distortion

1.0. Introduction.

Behavior of light propagation is a ubiquitous research tool in investigating materials. Scattering, absorption, and physicochemical properties of material media are main players in altering the characteristics of light as it travels, while revealing of the material itself. In fluorescence spectroscopy, light emitted by a fluorophore in a solvent also experiences scattering and absorption. The fluorophore or dye is subject to specific and non-specific interactions with the solvent and molecules in its neighborhood. These interactions are responsible for the intrinsic line shape of the emitted fluorescence, before distortion by scattering and absorption. The intrinsic line shape is the one of interest because it is a signature of the interactions and properties of the probe neighborhood. The effect of the interactions, referred to as physicochemical effects, are due to the physical and chemical nature of the solvent and any specific molecular interaction that might be present. Non-specific effects include those due to properties like density, pH, polarity, phase state, hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions, etc. Specific interactions include those due to particular molecular interactions as for example between a fluorophore conjugated antibody and a targeted antigen.

In biological tissue and colloidal solutions, specific and non-specific physicochemical interactions as well as scattering contribute to fluorescence line shape. Disentangling the various effects is a challenge. Distortions due to the wavelength dependence of scattering and absorption in media that scatter and absorb light are Inner Filter Effects (IFE) that interfere with interpretation in fluorescence applications such as in biological tissue diagnostics [1, 2]. Scattering is expected to reduce measured intensity and produce a red shift of the fluorescence peak because the blue part of the spectrum is scattered more than the red [1, 3]. Reabsorption of fluorescence by absorbers causes shifts of the intended fluorescence lines. Applications employing fluorescence intensities and peak positions as markers to investigate materials, when scattering and absorption are present, require extraction of the true or intrinsic fluorescence spectra [4]. Several methods have been proposed to correct for IFE in materials with absorbers [5–8]. A first but flawed recourse is an adaptation of Lambert-Beer law to transmission of fluorescence [9]. Denoting absorbance at wavelength λ by A (λ), the equation for the corrected spectrum is:

| (1) |

where Im and Iint are the measured and intrinsic intensities respectively at the emission wavelength λem and λexc is the excitation wavelength. The factor of two in the exponent on the right-hand side of eq. 1 arises because the average position of the fluorophore is at the center of the sample cuvette, and path length of travel for the fluorescence excitation and emission is half of the travel path length in an absorbance measurement.

In this equation, the absorbance A is usually associated with absorption but takes the role of attenuation when scattering alone is present because scattering causes loss in intensity. It quantifies attenuation of transmission through scattering media and applies only if Im is that of the unscattered photon [2, 3]. However, in a standard fluorescence spectrometer the photon collection and detection optics detect the scattered photon as well. Application of eq. 1 to fluorescence overestimates the attenuation and is therefore problematic [9, 10]. Eq. 1 is not reliable in the presence of absorbers either because of the existence of a distribution of path lengths, reabsorption of fluorescence, and multiple scattering [11]. Therefore, eq. 1 remains inadequate in practice. Recent methodologies based on Monte Carlo simulations that consider angular dependence of scattering cross-section and multiple scattering of photons as they migrate through a scattering medium have had better success with producing the true spectra [12, 13]. The significant outcome of these models is that the line shape barely changes when scattering alone is present but the effect on emitted intensity appears to be pronounced [13]. IFE for scattering was found to be insignificant [14]. Furthermore, the intensity actually increases with concentration of scatterers in cases investigated in this work as well as in others, contrary to the attenuation predicted by eq. 1 [13].

Important phenomena, not represented in correction models and interpretation methodologies, are the physicochemical dye-scattering particle-solvent interactions that distort line shape altering the intrinsic spectra. This work investigates the effects of such interactions and scattering on fluorescence in colloidal suspensions, toward the goal of disentangling the two effects. Colloidal systems serve as models of biological tissue where scattering, absorption, and physicochemical properties collectively contribute to line shape [13, 15]. Elucidation of these contributions is relevant in the determination of presence of pathological conditions.

Fluorescence emission of anionic fluorescein in aqueous scattering media made of colloidal solutions of (i) polystyrene nanoparticles (PSNP) of three different diameters: 100, 400, and 1000 nm; (ii) Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Chloride (CTAC) micelles; (iii) Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) micelles; (iv) 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) vesicles; (v) 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (DOPG) vesicles and in NaOH were measured for various concentrations. Fluorescein is water-soluble. The emission of fluorescein in water without colloids is therefore the intrinsic fluorescence. Additionally, laurdan fluorescence in phospholipid vesicle solutions was also measured for various vesicle concentrations. Laurdan, being water insoluble and lipophilic, resides in the phospholipid bilayer of the vesicle. Laurdan spectra can be measured only in the vesicle medium where scattering is inherent. As such, it appears that the intrinsic fluorescence spectra of laurdan in bilayers cannot be known. However, the effects of scattering of fluorescence by vesicles can be determined by observing the emission spectral changes as a function of vesicle concentration.

Fluorescein and laurdan are representative examples of fluorescence probes employed in the study of colloidal suspensions and biological tissue where scattering is inherent. Fluorescein and its derivatives (e.g. Alexa) are well-studied probes and popular choices for investigating biological tissue. Laurdan is abundantly used in the study of lipid bilayer membranes because its fluorescence emission is sensitive to polarity which changes according to the physical state of membranes. Polarity is higher in the tightly packed solid or gel state where the lipid tails are rigid and rod-like than in the loosely packed liquid state where the tails are fluid and mobile. In general, membranes coexist in a mixed state. Furthermore, lipid packing is inhomogeneous and depends on lipid composition. Laurdan emission comprises two peaks; one at about 430 – 440 nm from the higher polarity tightly packed regions and the other at 480 – 495 nm from the lower polarity loosely packed regions. Laurdan emission line shape changes according to the packing inhomogeneity present. To quantify packing heterogeneity, it is important to understand and disentangle the contributions of scattering and packing to line shape.

Spectral range of measurement in this study is 370 to 650 nm. Fluorescein and Laurdan fluorescence peaks are in the range 480 to 560 nm. Range of PSNP and vesicle size to peak wavelength ratio in this work is 0.2 to 2, where Mie scattering is prevalent. Rayleigh scattering is the mode in SDS and CTAC solutions, where the micelles are a few nm in diameter. The set of materials represent paradigms for strong (DOPC, DOPG), medium (PSNP), weak (SDS, CTAC), and absence of (NaOH) scattering.

Fluorescein emission comprises three lines and fits three Gaussians. Laurdan emits two lines and spectra fit to two lognormal distributions. The novel aspect of this work includes the fitting methodology and study of the behaviors of the individual line shape parameters. The three lines of fluorescein and two lines of Laurdan emission spectra are resolved with complementary use of the computed second harmonic (SH) of the original emission spectra. The SH methodology gives better resolution and precision than fitting the zeroth order spectra alone [16, 17]. Parameters of the individual lines, including peak intensity, peak wavelength, line width, and line asymmetry are examined against particle concentration. Peak shifts and intensity changes are consistent with predictions of physicochemical effects of particle-dye-solvent interactions rather than with scattering.

Line fitting and analyses of emission or absorption spectra are widely used to probe the properties of the environment of a probe molecule. In electron spin resonance (ESR), microwave absorption lines of spin probes are fit to Lorentzian, Gaussian, and Voigt functions [18, 19]. The Voigt line shape is a convolution of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions [20]. The fit results report on the local microviscosity and polarity. The ESR methodology has been developed and applied to ionic liquids, lipid solutions, and organic solvents [21–23]. The present fitting is a novel adaptation of the ESR fitting methodology to fluorescence.

In semiconductors excitonic emission lines and free to bound transitions are fit to Gaussians [24] Fitting the emission of colloidal Cadmium Selenide/Zinc Sulfide quantum dots (QDs) to a bi-Gaussian function led to the quantification of the trion (charged exciton) efficiency and its distinction from that of neutral excitons [25] Fitting the spectrally broad photoluminescence spectra of Zinc Tin Oxide (ZTO) nanowires to a bi-Gaussian function revealed the existence of two transitions attributed to defect states [26].

Emissions due to electronic transitions in organic fluorophores are fit to Gaussian or lognormal functions [16, 17] Fitting of fluorescence emission from dyes in lipid membranes provide information on the fluorescence anisotropy from which its location and orientation and the acyl lipid chain order can be determined [27–29]. Line shape analyses of vibronic transitions in molecular systems yield the anharmonicity of the surrounding potential. [30]

2.0. Materials and Methods.

2.1. Materials.

Aqueous suspensions of 10 mg/mL polystyrene nanoparticles (PSNP) of sizes 100, 400, and 1000 nm were obtained from Alpha Nanotech. Anionic fluorescein was from Sigma-Aldrich. The surfactants, CTAC and SDS were from Sigma. The phospholipid, DOPC and DOPG in chloroform were from Avanti Lipids and laurdan from AnaSpec.

2.2. Sample Preparation.

All solutions were prepared with distilled deionized water of pH = 5.8. Concentrations of PSNP in the aqueous suspensions were varied from 0 to 1.3 mg/ml. The highest concentration solution of 1.3 mg/ml polystyrene with 1 μM fluorescein was first prepared starting with the original 10 mg/ml solution diluted to 1.3 mg/ml and adding the required amount of fluorescein from a prepared stock of 1 mM fluorescein in water. The lower concentrations were obtained from this by diluting with 1 μM fluorescein in water without PSNP, so that fluorescein concentration remained constant. The pH values of the PSNP solutions changes from 5.8 in water to 6.5 in the 1.3 mg/ml PSNP solution.

For lipid solutions with laurdan, prepared stocks of 1 mM laurdan in chloroform and as purchased 25 mg/ml of lipid in chloroform were used. Multilamellar vesicles (MLV) of DOPC or DOPG with laurdan were prepared by the thin film hydration method. A mixture of appropriate amounts of lipid and laurdan in chloroform, required for 2mM of lipid and 7 μM laurdan, was dried by dry nitrogen gas. Water was added to the dry thin film left behind. The mixture was vortexed in a shaker for a few minutes and left stirring with a magnetic stirrer for about 24 hours. Concentrations less than 2 mM DOPC were obtained by diluting the original solution with water. The ratio [laurdan]/[DOPC] thus remained constant in all samples.

For lipid solutions with fluorescein, MLV solutions of the lipid alone were first prepared by drying the required amount of lipid/chloroform and adding water to the dry film followed by a few minutes of vortexing and 24 hours of magnetic stirring. Required amount from the fluorescein/water stock was added for a final concentration of 1 μM. Micellar solutions of 100 mM CTAC or SDS were prepared by mixing appropriate amounts of surfactant and water. Fluorescein was added to the solutions to a concentration of 1 μM. Lower surfactant or lipid concentrations were obtained by diluting the 100 mM surfactant or 2 mM lipid solutions with 1 μM fluorescein in water without surfactant or lipid so that the fluorescein concentration remained constant. The pH changes from 5.8 in water to 9.5 in 100 mM SDS, to 6.8 in 100 mM CTAC, to 8.7 in 2mM DOPC and DOPG.

2.3. Fluorescence Experiments.

Emission of fluorescein in the polystyrene suspensions was excited at 460 nm and that of laurdan in lipid vesicles at 360 nm. A Fluouromax-4 Spectroflourometer (Horiba Scientific) recorded fluorescein spectra from 465 to 700 nm and laurdan spectra from 365 to 650 nm, at a step size of 1 nm and a bandpass slit width of 1 nm. The instrument software provides the spectral data of fluorescence intensity in counts per second (CPS) vs wavelength. The data were exported to an excel file for further processing (as described in Section 2.4). Measurements were conducted at an ambient temperature of 23 °C. Spectra were measured with scattering solution without fluorophore as blanks. The blank subtractions provided a flat base line that aided better fitting.

2.4. Spectral Fitting.

Wavelength (λ) spectra were converted to wavenumber (k =1/λ) spectra by Jacobian transformation [31, 32]. SH of spectra were computed first as described in previous work [16]. SH is the computationally derived second harmonic by convolution of the measured spectra with the second harmonic modulation response function. The SH indicated three peaks for fluorescein and two for laurdan. Therefore, fluorescein spectra were fit to three Gaussians as a function of the wavenumber k, each in the form

| (2) |

where Im, km and HWHM are the peak height, peak position, and the half width at half maximum, respectively.

Laurdan emission spectra, shown to better fit lognormal distributions in previous works, were fit to two functions each in the form[16, 31, 33],

| (3) |

The parameters in eq. 3 are the peak height Im, peak position km, asymmetry function where kmin and kmax are the half-maximal positions, and width w = (kmax – kmin). Fits were performed by a Trust Region Reflective algorithm in MATLAB. The best fit was determined as the one with the flattest residuals of the fit to the spectra and of the SH of fit and SH of data and the best R2. The SH residuals, in particular, aid in the decision of the best fit.

2.5. Uncertainties.

All measurements were repeated at least three times. The maximum number of repeats (about 50) was for fluorescein in water because it was the starting sample for every data set and for each material. The 400 nm PSNP 0.032 mg/ml solution was repeated 15 times with three measurements on five different sample preparations. Mean and standard deviations of the line parameter values returned by fits to the repeated spectral measurements are reported.

3.0. Results.

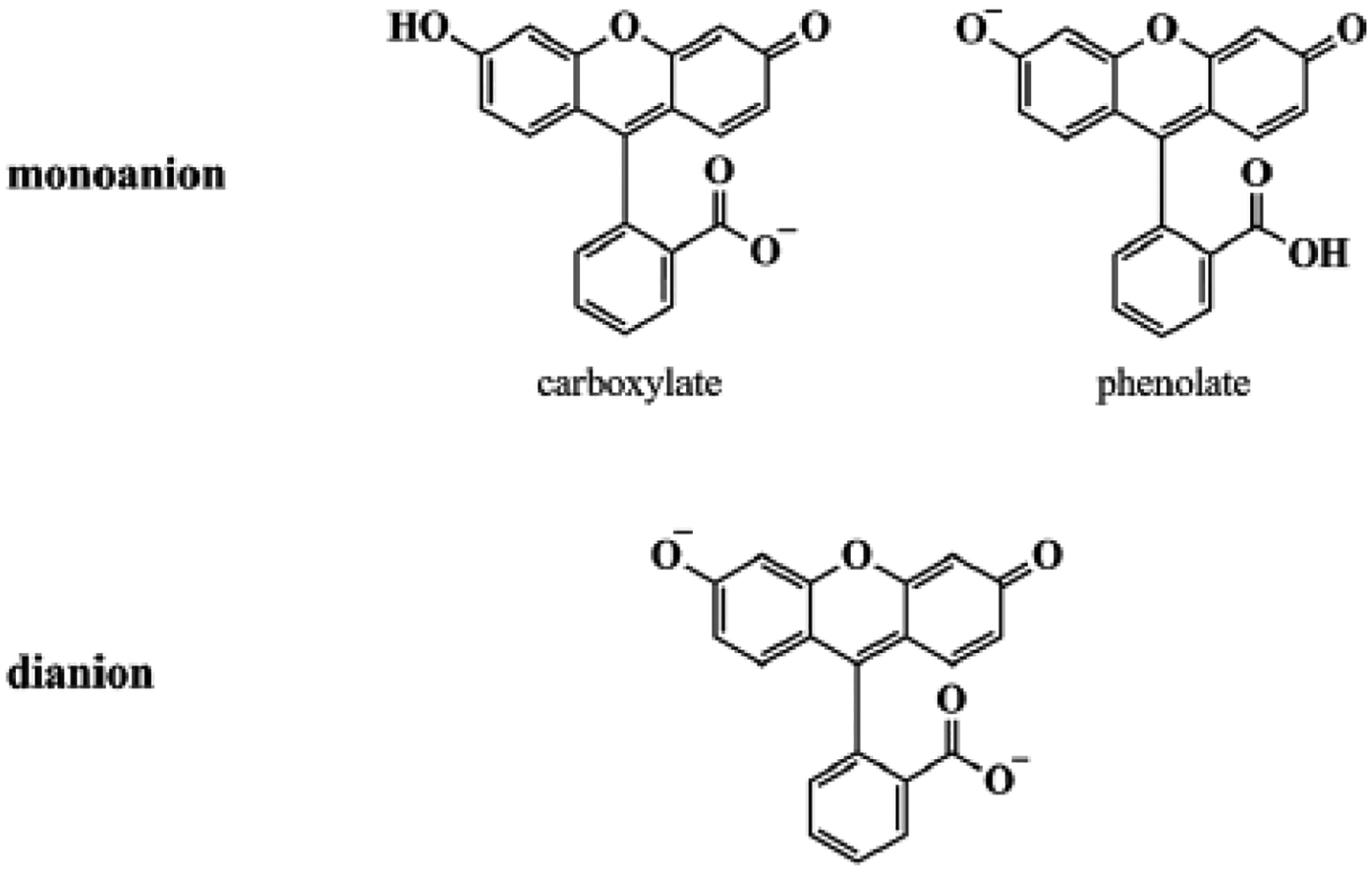

Fluorescence emission of anionic fluorescein in water comprises three lines originating from the three forms shown in Fig. 1 [34].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of anionic fluorescein.

The strongest emission, Peak 1, is due to the dianion. Monoanionic carboxylate emission, peak 2 is the next in strength and the weakest emission, peak 3, is from the phenolate. Metal ions, pH, and linking to polymeric colloidal particles are factors reported to affect the relative concentrations of the various forms and their fluorescence yields [35, 36]. In the present experiments, the positions of peaks 1, 2, and 3 in water are at 509.0 ±0.5, 531± 2, and 558 ± 1 nm, respectively, as obtained from fitting to three Gaussians. Peak 1 is the narrowest in line width with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 1162±17 cm−1, peak 3 is the broadest with an FWHM of 2544±25 cm−1. Peak 2 has an FWHM of 1729±34 cm−1. Standard deviations are from measurements on over fifty samples. Fluorescein spectrum in water is included in Fig. 2, together with PSNM and DOPC spectra.

Figure 2.

Measured fluorescein emission spectra in aqueous suspensions of (a) 400 nm PSNP; (c) DOPC vesicles. Normalized spectra of emission in (b) 400 nm PSNP; (d) DOPC vesicles. Legends in (a) and (c) apply to (b) and (d), respectively.

The spectra in Fig. 2 a and c are from aqueous suspensions of 400 nm PSNP and DOPC vesicles, respectively for various concentrations. Data for the 100 and 1000 nm PSNP and DOPG vesicles are similar; therefore, not shown. The same spectra normalized to equal peak values of unity in Fig. 2 b and d illustrate the character of overlap in line shape with the intrinsic spectrum (fluorescein in water). Lack of complete overlap of the normalized spectra is indicative of line shape change.

The line shape in DOPC solution is different from that in the PSNP solution, due apparently to the difference in relative intensities of peak 2 or 3 to peak 1. Spectra were fit to eq.2 as described in Section 2.4 for a quantitative determination of line shape parameter differences between the different materials and concentrations. Figs. 3 a and d present the measured spectra, fits, the three resolved lines and residuals of fit to fluorescein emission in the 400 nm PSNP solution at a concentration of 0.08 mg/ml and in 1 mM DOPC. Fig. 3 b, c and e, f are respectively the SH and residuals of SH of fit to SH of data. Presence of a third peak at a wavenumber lower than those of the two obvious peaks is indicated by the SH.

Figure 3.

Measured spectra, fit, resolved lines, residual and SH of data, fit and SH residual in aqueous suspensions of (a, b, c) 0.08 mg/ml 400 nm PSNP; (d, e, f) 1 mM DOPC vesicles. Legend in (a) applies also to (d).

Figure 4 shows fluorescein spectra in solutions of SDS and CTAC micelles and in NaOH. The measured spectra in Fig. 4 a, c, e give a view of the variation in emitted intensity. The normalized spectra in Fig. 4 b, d, and e are illustrative of changes in line shape. Graphics of fitted lines and SH are not shown, as they are similar to those in Fig. 3. CTAC (Fig. 4 c and d) shows shifts in peak positions, but changes in SDS and NaOH are less obvious. Line fitting better informs on the changes.

Figure 4.

Measured (a, c, e) and normalized (b, d, f) fluorescein emission spectra in solutions of (a, b) SDS; (c,d) CTAC; (e,f) NaOH. Concentrations in the legend in (a) apply also to (b, c), and (d). Concentrations in the legend in (e) are in μM and apply also to (f).

Line characteristics of peak wavelengths, FWHM, and peak intensities, returned by the fitting routine are examined as a function of particle concentration in Fig. 5–8. The error bars are the standard deviations from repeated measurements (see Section 2.5). It is clear from the variation in wavelength of peak 3 maximum in Fig. 5a that the materials fall into two groups. Peak 3 positions in the group comprising DOPC, DOPG, SDS, and NaOH decrease, and in the group of PSNP and CTAC increase with concentration. Wavelength maxima of peaks 1 and 2 increase for CTAC while there is no significant variation in the other cases. All PSNP data could not be included in the same figure, but are presented together with CTAC data in Fig. 5b.

Figure 5.

Peak wavelengths of fluorescein emission vs concentration in various suspensions. (a) DOPC, DOPG, SDS, NaOH; CTAC, 400 nm PSNP (•-top x-axis); 100 nm PSNP (▲, top x-axis). Only peak 3 positions for the PSNP are included. All PSNP peak positions are presented in (b)

(b) 100 nm PSNP; 400 nm PSNP; 1000 nm PSNP; CTAC (Δ, top x-axis).

Concentrations of SDS and CTAC are divided by 50 and that of NaOH is multiplied by 4.

Figure 8.

Laurdan emission spectra in DOPC vesicles. (a) Normalized spectra at the indicated concentrations in mM in the legend. (b) measured and fit spectra for 1 mM DOPC: Data (I); fit to two lognormal functions (I_fit); resolved lines (blue, Ib) and (red, Ir); residual. (c) SH of data and of fit; (d) SH residual of fit to data.

FWHM and peak height variations shown respectively in Fig. 6 a and b and Fig. 7 a and b exhibit the same group classification behavior as the peak positions. FWHM of the emissions in the PSNP and CTAC solutions (Fig. 6a) show a smaller variation with concentration than the FWHM in Fig. 6 b of the three lines from DOPC, DOPG, SDS, and NaOH solutions. FWHM of CTAC and PSNP exhibit differences in trend between each other as compared to a smoother and similar variation in the emission line widths for the group in Fig. 6b.

Figure 6.

FWHM in cm −1, of fluorescein emission lines vs concentration in solutions of (a) 100 nm PSNP; 400 nm PSNP; 1000 nm PSNP; CTAC. (b) DOPC; DOPG; SDS; NaOH. Concentrations of SDS and CTAC are divided by 50 and that of NaOH is multiplied by 4.

Figure 7.

Peak heights of fluorescein emission lines vs concentration in (a) 400 nm PSNP; CTAC. (b) DOPC; DOPG; SDS; and NaOH. Concentrations of SDS and CTAC are divided by 50 and that of NaOH is multiplied by 4.

Figure 7 a and b display intra group similarities in peak intensities. The most variation is in the intensities of peak 1. Intensities of peaks from DOPC, DOPG, SDS, and NaOH solutions increase with concentration followed by a plateau. PSNP (data shown only for the 400 nm PSNP) and CTAC display an increase followed by a decrease.

Fluorescence line shape, Fig. 8a, of lipophilic laurdan in DOPC bilayers is unaffected by DOPC concentration as the apparent overlap of the spectra would suggest. Fig. 8b shows the fit to two lognormal distributions (eq.3) for the 1 mM DOPC solution. The SH of the zeroth order spectrum in Fig. 8c clearly indicates two peaks. It is customary to refer to the longer and shorter wavelength lines as red and blue lines.

Fit results in Fig. 9 a and b illustrate line structure variation of each of the individual lines with concentration.

Figure 9.

Concentration dependence of line parameters from lognormal fits of laurdan spectra in DOPC vesicles. (a) Peak heights and positions of blue and red lines. (b) Line widths and line asymmetry parameters, ρ_blue and ρ_red.

The peak position of the red line decreases, barely, by about 1 nm from 493 nm and the blue line by 4.6 nm from 445 nm for a concentration change from 0.125 to 2 mM. Peak intensity of the red line increases by 15 % and the blue line intensity barely changes. The greatest change is in the width of the blue line (Fig. 9b). The asymmetries of the two lines (defined in Section 2.4) remain constant.

4.0. Discussion.

Scattering and decrease in its cross-section with wavelength predicate attenuation, narrowing of line width and a red shift in the peak; if only unscattered photons are detected. None of this is borne out by the data suggesting reasonably that the scattered photon is detected. A fluorescent photon has a greater chance of entering the detector when scattered multiple times, than when scattering is not present or weak. Detection of scattered photons minimizes wavelength dependent effects that induce a red shift and distortion of line shape. Models of photon migration through scattering media show that the probability of escaping from the medium may increase as well as decrease as a function of the number of scattering events depending on scattering anisotropy, collection geometry and boundary conditions [2] [12]. A decrease in fluorescence from its intrinsic value in the weak scattering limit followed by an increase in the diffuse scattering limit without change in line shape has been observed in model tissue samples [13]. Standard fluorescence measuring instruments employing cuvettes of 1 cm path length are generally equipped with optics that collect and detect not just the unscattered photon but also those that are scattered multiple times and those scattered in the forward direction. Furthermore, experiments in purely scattering solutions report only changes in intensity and no change in line shape [13]. IFE on line shape due to scattering can be concluded to be insignificant [14].

Results on line shape and intensity changes in all of the colloidal systems studied, argue for the role of physicochemical effects of the colloidal particle in inducing the observed changes. Emission peak wavelengths, peak intensities and FWHM variation with concentration in DOPC, DOPG, and SDS are similar to that in NaOH solutions. Peak intensities in NaOH solutions have been reported to increase, as also observed in this work, with NaOH up to a pH of 8.3 and then plateau [37]. Peak 3 blue shifts in NaOH solutions and in SDS, DOPC, and DOPG as well with increasing concentrations (Fig. 5a). Solutions of SDS, DOPC, and DOPG are alkaline with pH increasing from 7 to 9 with increase in concentration of the surfactant or lipid in this study. Changes in fluorescein spectral characteristics must therefore be largely due to the increasing alkalinity of the medium that occurs upon addition of SDS, DOPC, or DOPG.

Surface charge of SDS micelles, DOPG vesicles and the surface-exposed phosphate charge of DOPC is negative. Anionic fluorescein prefers the aqueous region and senses the pH of the solvent medium rendered alkaline by SDS or the phospholipids. On the other hand, electrostatic attraction puts anionic fluorescein at the surface of the cationic CTAC micelles (Fig. 5 a, b). This attractive interaction is strong enough to red shift the positions of all of the three peaks. In PSNP solutions, peak 3 red shifts by about 8 nm and peak 2 by about 3 nm (Fig. 5b). These shifts are likely due to interaction of monoanionic fluorescein with the hydrophobic PSNP surface. A stronger interaction with the phenolate than carboxylate is to be expected. The larger red shift in peak 3 than in peak 2 would justify assignment of peak 3 to phenolate. Such shifts were observed between anionic fluorescein emission in ethanol and from fluorescein cast on polystyrene coated glass surfaces [38]. These shifts were attributed to ion-π and π-π interactions of monoanionic fluorescein with the hydrophobic PSNP surface. Peak 1, due to the dianion, is relatively invariant in position. Dianion is not likely to interact with hydrophobic surfaces and its fluorescence does not experience a shift.

Interestingly, the measured fluorescence intensity profile in PSNP solutions vs concentration (Fig. 7a) resembles that of the calculated escape probability vs number of scattering events obtained in photon migration models, when considering that the number of scattering events is proportional to the concentration of particles [12, 13]. The observed peak height profile in PSNP solutions appears to be an experimental realization of the photon migration model. Such a profile is not observed in the alkaline group (SDS, DOPC, DOPG). Physicochemical effects are overpowering for these materials and the profile is reflective of that in NaOH. Scattering effects contribute only partially to intensity changes.

Another point of note is that the peak positions in PSNP solutions are more or less a function of concentration in mg/ml and not on particle concentration. This also argues for presence of interaction. Number of interaction sites is equal to the surface area X number of particles. At a given mg/ml concentration, surface area increases but the PSNP particle concentration decreases with particle diameter. These opposing tendencies result in the number of interaction sites and hence interaction associated spectral changes to be a function of the mg/ml concentrations rather than the number concentration of particles.

Scattering should affect laurdan and fluorescein spectra in a like manner, particularly because the spectral wavelengths are about the same for the two fluorophores. However, this is contrary to observations. Laurdan fluorescence line shape in lipid vesicles, in contrast to that of fluorescein, does not appear to show a concentration dependence. Laurdan resides in the lipid bilayer and senses lipid-water interface polarity. A decrease in line width of the blue line (Fig. 9b) indicates a decrease in polarity as observed in previous work as well, on several solvents differing in polarity [16]. Decrease in polarity would also explain the decrease in peak wavelength. A well-known observation in micellar systems is the growth of micelles accompanied by decrease in interface polarity with surfactant concentration and likely applies to lipid vesicles as well [39, 40].

5.0. Conclusions.

Spectral line shape of fluorescence emission from fluorophores in scattering media is not distorted by scattering. The two important findings of this work are: (1) effect of scattering is limited to intensity changes, which obviates the need for line shape corrections for scattering. (2) Line shape parameter changes are due to particle-dye-solvent interactions. Light collection optics together with redirection into the detector of multiply scattered photons and detection of forward scattered photons are possible reasons for mitigation of scattering effects on line shape. Anionic fluorescein does not interact with SDS and lipid vesicle surfaces. It remains in the aqueous medium and senses the changing pH. The observed blue shift of the monoanion peak and decrease in FWHM with SDS or lipid concentration are due to increase in alkalinity of the solvent medium as in NaOH solutions. Intensity changes in the alkaline colloidal solutions are due to scattering as well as pH changes. A direct interaction of anionic fluorescein with cationic CTAC and hydrophobic PSNP particle surfaces produces a red shift in the spectrum. Intensity changes in the particle-probe interacting systems are due to scattering and interaction. Conclusions based on intensity changes of emissions in scattering media can be unreliable. Physicochemical effects are the dominant contributors to line shape. The present approach of studying the behavior of the individual resolved line shape parameters in scattering and non-scattering media makes possible the conclusion that direct particle-dye interaction and particle-solvent interaction are responsible for line shape changes. Correction for scattering effects is not necessary if just line shape is sufficient. Line shape changes due to physicochemical effects serve as better markers of interactions and reactions than intensity. However, if a specific interaction in a scattering medium is being investigated, then the correct intrinsic spectra is the one obtained for that particular scattering medium in the absence of the targeted interaction because fluorophore interactions with the scattering particle itself and particle concentration dependent modification of physicochemical properties redefine intrinsic spectra. Thus, the methodology and findings presented should find applications in analyses that require disentangling the contributions of scattering, specific, and non-specific interactions to fluorescence or absorption spectra. One such application is in medical diagnostics where clinicians look for the presence of a specific interaction manifested by line shape changes.

Acknowledgement.

R. Ranganathan gratefully acknowledges NIH for their support through grant contract # 1SC3GM122499-01A1 and 1SC3GM144158-01. L. M. D. Muñoz and M. Peric gratefully acknowledge support from NSF RUI (grant no. 1856746). R.R. thanks Dr. Taeboem Oh, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, CSUN, for useful discussions.

References

- [1].Panigrahi SK, Mishra AK, Inner filter effect in fluorescence spectroscopy: As a problem and as a solution, Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews, 41 (2019) 100318. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cheong WF, Prahl SA, Welch AJ, A review of the optical properties of biological tissues, IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics, 26 (1990) 2166–2185. [Google Scholar]

- [3].He GS, Qin H-Y, Zheng Q, Rayleigh, Mie, and Tyndall scatterings of polystyrene microspheres in water: Wavelength, size, and angle dependences, Journal of Applied Physics, 105 (2009) 023110. [Google Scholar]

- [4].French SA, Territo PR, Balaban RS, Correction for inner filter effects in turbid samples: fluorescence assays of mitochondrial NADH, American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology, 275 (1998) C900–C909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang T, Zeng L-H, Li D-L, A review on the methods for correcting the fluorescence inner-filter effect of fluorescence spectrum, Applied Spectroscopy Reviews, 52 (2017) 883–908. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kubista M, Sjöback R, Eriksson S, Albinsson B, Experimental correction for the inner-filter effect in fluorescence spectra, Analyst, 119 (1994) 417–419. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gu Q, Kenny JE, Improvement of Inner Filter Effect Correction Based on Determination of Effective Geometric Parameters Using a Conventional Fluorimeter, Analytical Chemistry, 81 (2009) 420–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Larsson T, Wedborg M, Turner D, Correction of inner-filter effect in fluorescence excitation-emission matrix spectrometry using Raman scatter, Analytica Chimica Acta, 583 (2007) 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mendonça A, Rocha AC, Duarte AC, Santos EBH, The inner filter effects and their correction in fluorescence spectra of salt marsh humic matter, Analytica Chimica Acta, 788 (2013) 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Panigrahi SK, Mishra AK, Study on the dependence of fluorescence intensity on optical density of solutions: the use of fluorescence observation field for inner filter effect corrections, Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, 18 (2019) 583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Credi A, Prodi L, From observed to corrected luminescence intensity of solution systems: an easy-to-apply correction method for standard spectrofluorimeters, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 54 (1998) 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wu J, Feld MS, Rava RP, Analytical model for extracting intrinsic fluorescence in turbid media, Appl. Opt, 32 (1993) 3585–3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Müller MG, Georgakoudi I, Zhang Q, Wu J, Feld MS, Intrinsic fluorescence spectroscopy in turbid media: disentangling effects of scattering and absorption, Appl. Opt, 40 (2001) 4633–4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Xu JX, Vithanage BCN, Athukorale SA, Zhang D, Scattering and absorption differ drastically in their inner filter effects on fluorescence, resonance synchronous, and polarized resonance synchronous spectroscopic measurements, Analyst, 143 (2018) 3382–3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Amar A, Bigio I, Correction of fluorescence spectra using data from elastic scattering spectroscopy and a modified Beer’s law, (2002).

- [16].Ranganathan R, Burkin AJ, Peric M, Complementary Fluorescence Emission and Second Harmonic Spectra Improve Bilayer Characterization, Journal of Fluorescence, 30 (2020) 205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ranganathan R, Alshammri I, Peric M, Lipid Organization in Mixed Lipid Membranes Driven by Intrinsic Curvature Difference, Biophysical Journal, 118 (2020) 1830–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bales BL, Peric M, EPR Line Shifts and Line Shape Changes Due to Spin Exchange of Nitroxide Free Radicals in liquids, J. Phys. Chem. B, 101 (1997) 8707–8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Peric I, Merunka D, Bales BL, Peric M, Hydrodynamic and Nonhydrodynamic Contributions to the Bimolecular Collision Rates of Solute Molecules in Supercooled Bulk Water., J. Phys. Chem. B, 118 (2014) 7128–7135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bales BL, Inhomogeneously Broadened Spin-Label Spectra, in: Reuben L.J.B.a.J. (Ed.) Biological Magnetic Resonance, Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, 1989, pp. 77–130. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Peric M, Alves M, Bales BL, Combining precision spin-probe partitioning with time-resolved fluorescence quenching to study micelles: Application to micelles of pure lysomyristoylphosphatidylcholine (LMPC) and LMPC mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate, Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 142 (2006) 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Singh J, Peric M, Interaction of the β amyloid – Aβ(25–35) – peptide with zwitterionic and negatively charged vesicles with and without cholesterol, Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 216 (2018) 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Slade J, Merunka D, Peric M, Radical Diffusion Crossover Phenomenon in Glass-Forming Liquids, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 13 (2022) 3510–3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bartram RH, Vassell MO, Zemon S, Analysis of fluorescence line shapes for free-to-bound transitions in semiconductors, Journal of Applied Physics, 60 (1986) 4248–4252. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xu X, Enhanced trion emission from colloidal quantum dots with photonic crystals by two-photon excitation, Sci Rep, 3 (2013) 3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yakami BR, Poudyal U, Nandyala SR, Rimal G, Cooper JK, Zhang X, Wang J, Wang W, Pikal JM, Steady state and time resolved optical characterization studies of Zn2SnO4 nanowires for solar cell applications, Journal of Applied Physics, 120 (2016) 163101. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kaiser RD, London E, Location of diphenylhexatriene (DPH) and its derivatives within membranes: comparison of different fluorescence quenching analyses of membrane depth, Biochemistry, 37 (1998) 8180–8190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Poojari C, Wilkosz N, Lira RB, Dimova R, Jurkiewicz P, Petka R, Kepczynski M, Róg T, Behavior of the DPH fluorescence probe in membranes perturbed by drugs, Chem Phys Lipids, 223 (2019) 104784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].do Canto A, Robalo JR, Santos PD, Carvalho AJP, Ramalho JPP, Loura LMS, Diphenylhexatriene membrane probes DPH and TMA-DPH: A comparative molecular dynamics simulation study, Biochim Biophys Acta, 1858 (2016) 2647–2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Anda A, De Vico L, Hansen T, Abramavičius D, Absorption and Fluorescence Lineshape Theory for Polynomial Potentials, J. Chem. Theory Comput, 12 (2016) 5979–5989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Bacalum M, Zorila B, Radu M, Fluorescence spectra decomposition by asymmetric functions: Laurdan spectrum revisited, Analytical Biochemistry, 440 (2013) 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mooney J, Kambhampati P, Get the Basics Right: Jacobian Conversion of Wavelength and Energy Scales for Quantitative Analysis of Emission Spectra, The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 4 (2013) 3316–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Burstein EA, Emelyanenko VI, Log-Normal Description of Fluorescence Spectra of Organic Fluorophores, Photochemistry and Photobiology, 64 (1996) 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sjöback R, Nygren J, Kubista M, Absorption and fluorescence properties of fluorescein, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 51 (1995) L7–L21. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Siejak P, Frąckowiak D, Spectral Properties of Fluorescein Molecules in Water with the Addition of a Colloidal Suspension of Silver, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 109 (2005) 14382–14386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Panchompoo J, Aldous L, Baker M, Wallace MI, Compton RG, One-step synthesis of fluorescein modified nano-carbon for Pd(ii) detection via fluorescence quenching, Analyst, 137 (2012) 2054–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zhu H, Derksen RC, Krause CR, Fox RD, Brazee RD, Ozkan EH, Fluorescent Intensity of Dye Solutions under Different pH Conditions. American Society for Testing and Materials, Journal of ASTM International, 2(6) (2005) 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mullen M, Fontaine N, Euler WB, A Spectroscopic Study of Xanthene Dyes on a Polystyrene Surface: an Investigation of Ion-π Interactions at Polymer Interfaces, Journal of Fluorescence, 30 (2020) 811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ranganathan R, Tran L, Bales BL, Surfactant and Salt Induced Growth of Normal Alkyl Sodium Sulfate Micelles Well above Their CMC, J. Phy. Chem. B, 104 (2000) 2260–2264. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bales BL, Ranganathan R, Griffiths PC, Characterization of Mixed Micelles of SDS and a Sugar Based Nonionic Surfactant as a Variable Reaction Medium, J. Phys. Chem. B, 105(31) (2001) 7465–7473. [Google Scholar]