Abstract

Aquaporins (AQPs) are transmembrane water channel proteins that regulate the movement of water through the plasma membrane in various tissues including cornea. The cornea is avascular and has specialized microcirculatory mechanisms for homeostasis. AQPs regulate corneal hydration and transparency for normal vision. Currently, there are 13 known isoforms of AQPs that can be subclassified as orthodox AQPs, aquaglyceroporins (AQGPs), or supraquaporins (SAQPs) / unorthodox AQPs. AQPs are implicated in keratocyte function, inflammation, edema, angiogenesis, microvessel proliferation, and the wound-healing process in the cornea. AQPs play an important role in wound healing by facilitating the movement of corneal stromal keratocytes by squeezing through tight stromal matrix and narrow extracellular spaces to the wound site. Deficiency of AQPs can cause reduced concentration of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) leading to reduced epithelial proliferation, reduced/impaired keratocyte migration, reduced number of keratocytes in the injury site, delayed and abnormal wound healing process. Dysregulated AQPs cause dysfunction in osmolar homeostasis as well as wound healing mechanisms. The cornea is a transparent avascular tissue that constitutes the anterior aspect of the outer covering of the eye and aids in two-thirds of visual light refraction. Being the outermost layer of the eye, the cornea is prone to injury. Of the 13 AQP isoforms, AQP1 is expressed in the stromal keratocytes and endothelial cells, and AQP3 and AQP5 are expressed in epithelial cells in the human cornea. AQPs can facilitate wound healing through aid in cellular migration, proliferation, mitigation, extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and autophagy mechanism. Corneal wound healing post-chemical injury requires an integrative and coordinated activity of the epithelium, stromal keratocytes, endothelium, ECM, and a battery of cytokines and growth factors to restore corneal transparency. If the chemical injury is mild, the cornea will heal with normal clarity, but severe injuries can lead to partial and/or permanent loss of corneal functions. Currently, the role of AQPs in corneal wound healing is poorly understood in the context of chemical injury. This review discusses the current literature and the role of AQPs in corneal homeostasis, wound repair, and potential therapeutic target for acute and chronic corneal injuries.

Keywords: Aquaporins, Corneal endothelium, Corneal epithelium, Corneal wound healing, Inflammation, Stroma, Sulfur mustard, Wound healing

1. Introduction

Water, the most abundant molecule in tissues, is known to constitute 50–60% of the human body. The interplay between intracellular and extracellular water content is vital for homeostasis at the cellular, tissue, and organ level, thus the regulation of water flow is critical for cellular survival (Brown, 2017; Rasheed Ibrahim et al., 2019). The exchange of water at a cellular level can occur via passive diffusion; however, this mechanism of flow is slow-moving and can be saturated in times of stress (Brown, 2017; Mariajoseph-Antony et al., 2020). Aquaporins (AQPs) are ubiquitous small integral transmembrane proteins found in every phylogenetic kingdom that facilitate the accelerated transfer of water across biological membranes (Day et al., 2014; Yool and Campbell, 2012). Peter Agre first discovered AQP1, the first member of the AQPs family and received Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2003 (Schey et al., 2014). Studies indicate that AQPs have also been shown to expedite glycerol, urea, ammonia, and hydrogen peroxide transport alluding to a dynamic role in other aspects of cellular regulation (Kitchen et al., 2015; Rojek et al., 2008; Verkman, 2005). AQPs are implicated in the molecular regulation of osmolarity, cell migration, junction adhesion, regulation of surface protein expression, cellular proliferation, extracellular matrix (ECM) stress regulation, energy metabolism, and cellular water regulation (Calamita and Delporte, 2021; Conner et al., 2013; Ishibashi et al., 2021; Nong et al., 2021; Rasheed Ibrahim et al., 2019). Similarly, at an organ level, AQPs facilitate the viscosity of pulmonary fluid secretions, cerebral fluid dynamics, pancreatic insulin secretion, ocular visual acuity, triglyceride transport between the liver and adipose tissue, and renal osmolarity regulation (Frühbeck et al., 2006; Kitchen et al., 2020; Verkman, 2007; Yadav et al., 2020). Defective or dysregulated AQPs are known to play a role in a variety of pathologies including post-stroke cerebral edema, breast cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), obesity, and a variety of trauma-related injuries (Ala et al., 2021; He and Yang, 2019; Li et al., 2018; Madeira et al., 2015; Thériault et al., 2018; Traberg-Nyborg et al., 2022; Tran et al., 2010; Yadav et al., 2020).

AQPs are proteins that are water channels forming pores and transporting biological molecules through the cell membranes. There are 13 known subtypes of AQPs (AQP0 – AQP12). Based on permeability to various molecules AQPs are categorized into three types; orthodox AQPs, aquaglyceroporins (AQGPs), and unorthodox or supraquaporins (SAQPs) (Verkman, 2013). Orthodox AQPs consist of AQP0, AQP1, AQP2, AQP4, AQP5, AQP6 and AQP8. AQGPs include AQP3, AQP7, AQP9 and AQP10, whereas SAQPs are made up of AQP11 and AQP12 (Delgado-Bermúdez et al., 2019). Orthodox AQPs facilitate water transport primarily. AQGPs are known to transport glycerol and other small molecules. SAQPs are the unorthodox AQPs that are involved in the transport of glycerol and hydrogen peroxide (Brown, 2017; Rasheed Ibrahim et al., 2019; Verkman, 2013).

AQPs are implicit in homeostasis and stress responses, including inflammatory response and facilitation of the immune system, as well as ocular diseases and ocular injury due to trauma (da Silva and Soveral, 2021; Kenney et al., 2004; Meli et al., 2018; Prangenberg et al., 2021; Schey et al., 2014). The cornea is the anterior part of the eye composed of transparent avascular tissue that provides protection to the inner eye without compromising visual acuity (Meek and Knupp, 2015). Due to the cornea’s direct exposure to the external environment, it is highly susceptible to injury and infection. The corneal wound healing process is a dynamic, complex mechanism involving a variety of cells, growth factors, cytokines, growth factors, and swelling mechanisms (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015; Maycock and Marshall, 2014; Wilson, 2020). AQPs maintain homeostasis through the regulation of tissue osmolarity and wound- healing mechanisms.

Wound healing entails a melody of intertwined processes of tissue repair involving a variety of immune cells, proteases, growth factors, chemotactic molecules, cytokines, and chemokines (Guo and DiPietro, 2010; Raziyeva et al., 2021). Due to the complexity of wound healing any dysregulation, prolongation, or abnormal wound healing can lead to delayed/poor healing, infection, hypertrophic scaring, ulceration, improper organ function, and persistent wounds (Kamil and Mohan, 2021; Miyagi et al., 2018; Raziyeva et al., 2021). In the cornea, insufficient wound healing can lead to loss of the refractive nature of the cornea which is vital for normal vision (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Severe injury or disease can lead to loss of visual acuity or blindness. Inflammatory response, migration, and proliferation rates are key aspects of corneal wound healing aided by AQPs (Bollag et al., 2020a; Fluhr et al., 2008; Holm, 2016; Kumar et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021). The effect of dysregulated AQPs in abnormal corneal wound healing is not well understood currently. Development of novel therapeutic regulation of AQPs enhances corneal wound healing mechanisms and corneal homeostasis. This review aims to highlight the role of AQPs in corneal wound healing and homeostasis.

2. Aquaporins

AQPs are a family of ubiquitous homotetrameric integral membrane proteins that play a role in osmolar regulation via opening or closing the channel (gating) and protein shuttling throughout various cellular compartments (trafficking) (Rasheed Ibrahim et al., 2019). AQP proteins are composed of 300 amino acids (AAs) with the highly conserved Asn-Pro-Ala (NPA) motif (Yool and Campbell, 2012). AQP monomers contain 6 transmembrane helical segments that form a pore with short helical tails exposed to the cytosolic compartment (Nesverova and Törnroth-Horsefield, 2019; Yool and Campbell, 2012). Each AQP monomer acts independently of one another, and the center of the tetramer also acts as a pore (Markou et al., 2022). AQPs are classically known as ubiquitous water channels; however, since the discovery of AQP1, previously known as CHIP28, the channels have been shown to play a role in a variety of other regulatory functions (Brown, 2017). AQPs are proteins that are water channels forming pores and transporting biological molecules through the cell membranes. There are 13 known subtypes of AQPs (AQP0 – AQP12). Based on permeability to various molecules AQPs are categorized into three types; orthodox AQPs, aquaglyceroporins (AQGPs), and unorthodox or supraquaporins (SAQPs) (Verkman, 2013). Orthodox AQPs consist of AQP0, AQP1, AQP2, AQP4, AQP5, AQP6 and AQP8. AQGPs include AQP3, AQP7, AQP9 and AQP10, whereas SAQPs are made up of AQP11 and AQP12 (Delgado-Bermúdez et al., 2019). Orthodox AQPs are shown to primarily participate in osmolar regulation through the facilitation of water transport. AQGPs are known to transport glycerol and other small molecules. AQGPs are a subclass of AQPs known to transport glycerol and other small molecules to allow for a regulatory function in a variety of cellular functions (Pimpão et al., 2022). SAQPs are the unorthodox AQPs that are involved in the transport of glycerol and hydrogen peroxide (Brown, 2017; Rasheed Ibrahim et al., 2019; Verkman, 2013). SAQPs are involved in the intracellular mitigation of oxygen radicals in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and have little role in water transport (Ishibashi et al., 2021; Morishita et al., 2005). The regulatory aspects of AQPs are necessary for cellular homeostasis in tissue throughout the body including in the cornea (Schey et al., 2014; Verkman et al., 2008). Studies have shown the ability of AQP to transport other molecules including ammonia, urea, carbon dioxide, mercury, arsenous acid, lactic acid, and ions such as potassium and chloride (Alishahi and Kamali, 2019; Assentoft et al., 2016; Geistlinger et al., 2022; Laforenza et al., 2013; Qin and Boron, 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2019; Tong et al., 2013). Nonetheless, additional in-depth research studies are needed to support this notion.

Regulatory function, activation, and permeability of AQPs occur via a variety of mechanisms that are dependent on the specific AQP subclass. A summarization of the various AQP subclassification, functions, permeability and other molecules of interest is shown in Table 1 (Alishahi and Kamali, 2019; Assentoft et al., 2016; Geistlinger et al., 2022; Iena and Lebeck, 2018; Laforenza et al., 2013; Pellavio and Laforenza, 2021; Qin and Boron, 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2019; Tong et al., 2013; Verkman, 2013).

Table 1.

AQP isoforms and their respective subclass, general functions, the permeability of glycerol, urea, ammonia, hydrogen peroxide, and other molecules are postulated to be regulated by each isoform.

| AQPs | Subclass | AQP Function(s) | Glycerol Permeability | Urea Permeability | Ammonia Permeability | Hydrogen Peroxide Permeability | Other Molecules of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQP0 | Orthodox | Gating | No | No | No | No | cations (Cs+, Na+, and K+), CO2, ascorbic acid |

| AQP1 | Orthodox | Trafficking, Gating | No | No | No | Np | monovalent Cations, NO, CO2 |

| AQP2 | Orthodox | Trafficking | No | No | No | No | Unknown |

| AQP3 | AQGP | Trafficking | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | silicon, arsenite |

| AQP4 | Orthodox | Trafficking | No | No | Yes | No | CO2 |

| AQP5 | Orthodox | Trafficking | No | No | No | No | CO2, Ca2+ |

| AQP6 | Unclear | Gating | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | anions (NO3-, I-, Br-, and Cl-), CO2 |

| AQP7 | AQGP | Trafficking | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | arsenite, antomonite, silicon |

| AQP8 | Orthodox | Trafficking | No | Yes | Yes | No | arsenous acid |

| AQP9 | AQGP | Trafficking | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | lactic acid, arsenous acid, antomonite, silicon, CO2 |

| AQP10 | AQGP | Trafficking | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | arenic, antomonite, silicon |

| AQP11 | SAQP | Trafficking | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unknown |

| AQP12 | SAQP | Trafficking | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unknown |

AQPs distribution and physiological function vary widely throughout the human body (Schey et al., 2014). The understanding of their roles elsewhere in the body allows for better comprehension of the possible functions each play in the cornea. The orthodox AQPs (AQPs 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8) facilitate water transport throughout a variety of tissues (Kitchen et al., 2015). Recently it has also been postulated that this subclass also transports other compounds. AQP0 is found to maintain transparency of the lens of the eye through the regulation of water transport (Nesverova and Törnroth-Horsefield, 2019). AQP0 may also play a role in cation and ascorbic acid transport in the lens (Tong et al., 2013). AQP1 is found in a variety of tissue including the brain, eyes, heart, muscle, kidney, trachea, lung, gastrointestinal tract, salivary glands, pancreas, erythrocytes, spleen, liver, ovaries, and testis (Schey et al., 2014). Osmotic water regulation is the key aspect of AQP1 function though it has been shown to also play a role in CO2 regulation in tissues with low oxygen content (Tran et al., 2010). AQP2 is found in the ear, kidneys, and ductus deferens and maintains urine concentration as well as osmolar homeostasis (Schey et al., 2014). AQP4 is present in the brain, eyes, heart, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, muscle, trachea and salivary glands (Assentoft et al., 2016). AQPs regulate cell-cell-adhesiveness and water channels in epithelialphysiology, and in the wound healing process (Login et al., 2019). In the central nervous system (CNS), AQP4 is known to play a role in the reduction of cytotoxicity and increased vasogenic CNS edema (Kitchen et al., 2020). AQP4 has also been shown to play a role in the homeostasis of retinal cells (Chen et al., 2022; Li et al., 2014). AQP5 regulates water permeability in the salivary glands, eyes, lungs, trachea, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, ovaries, and kidneys (Burghardt et al., 2003; Horsefield et al., 2008; Schey et al., 2014; Sidhaye et al., 2012). AQP5 has also been shown to facilitate CO2 permeability in the brain (Alishahi and Kamali, 2019). AQP6 function is not clearly understood as some studies suggest it has a function in glycerol transport and thus should be classified as an AQGP; however, AQP6 primarily functions in glomerular filtration and tubular endocytosis in the kidney and acid-base metabolism in the brain (Qin and Boron, 2013; Schey et al., 2014; Soler et al., 2021). AQP8 functions in water, urea, and ammonia transport in the liver, pancreas, lungs, kidney, ovaries, and testis (Pellavio and Laforenza, 2021; Schey et al., 2014). The water trafficking function of AQP8 is crucial for spermatogenesis and sperm motility (Pellavio and Laforenza, 2021).

The AQGPs (AQP3, 7, 9, and 10) facilitate water and glycerol transport (Kitchen et al., 2015; Rojek et al., 2008). The transport of glycerol allows AQGPs to participate in a variety of functions facilitating metabolism and cellular migration (Arif et al., 2018; Iena and Lebeck, 2018; Rose et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2020). AQP3 transports water, glycerol, ammonia, silicon, and arsenite. AQP3 is found in the eyes, kidney, brain, trachea, salivary glands, heart, ovaries, gastrointestinal tract, liver, respiratory tract, brain, erythrocytes, fat, and spleen (Pimpão et al., 2022; Schey et al., 2014). AQP3 regulates skin hydration, cellular proliferation, and cellular migration during wound healing (Calamita and Delporte, 2021; Choudhary et al., 2017; Fluhr et al., 2008; Login et al., 2019). AQP3 has also been seen to facilitate migration and invasion in embryonic trophoblast (Nong et al., 2021). AQP7, found in the testis, heart, kidney, ovaries, and fat participates in energy homeostasis, spermatogenesis, triglyceride synthesis, and glycerol efflux from adipose tissue (Iena and Lebeck, 2018; Schey et al., 2014). AQP9 regulates aspects of neutrophil migration, metabolism of neurons, and metabolic regulation of adipose tissue (Holm et al., 2016; Mizokami et al., 2011). AQP10 facilitates water and glycerol permeability in the gastrointestinal tract, skin, and adipose tissue (Calamita and Delporte, 2021). The SAQPs participate in stress mitigation through intracellular processes. Specifically, AQP11 and AQP12 have been shown to be permeable to hydrogen peroxide. The SAQPs regulate the permeability of the ER to help alleviate reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress (Morishita et al., 2005). AQP11 is found in the eye, kidney, testis, liver, and brain (Ishibashi et al., 2021; Schey et al., 2014). AQP12 is present in the pancreas (Schey et al., 2014).

3. Aquaporins in the cornea

The cornea is a highly specialized avascular and transparent tissue, and its function is regulated by fluid transport within corneal layers and adjacent tissues. Stroma is the thickest layer and constitutes ~90% of corneal structure and thus is the primary site of water retention in the cornea (Hamann, 2002; Mohan et al., 2022). Stromal transparency requires precise maintenance of extracellular water volume to preserve visual acuity (Hayes et al., 2017). The two layers, external epithelium and endothelium, assist the corneal stroma to maintain the required physiological hydration (Hayes et al., 2017; Meek and Knupp, 2015). The epithelium regulates osmotic flux across the external ocular surface and aids tear film composition and volume (Bollag et al., 2020b) while endothelium expedites aqueous humor flow into the stroma (Bonanno, 2003). In addition, the transport of anions by the endothelium facilitates stromal dehydration (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). The maintenance of this dynamic relationship is facilitated by the presence of AQPs (Giblin et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2004; Maycock and Marshall, 2014). Aquaporins play an essential role in transmembrane water movements across the cornea and conjunctiva to maintain tear film osmolarity and normal stromal thickness. In general, AQPS expression and distribution are mostly similar in mouse, rabbit, and human corneas, however, this needs verification through in-depth comparative studies.

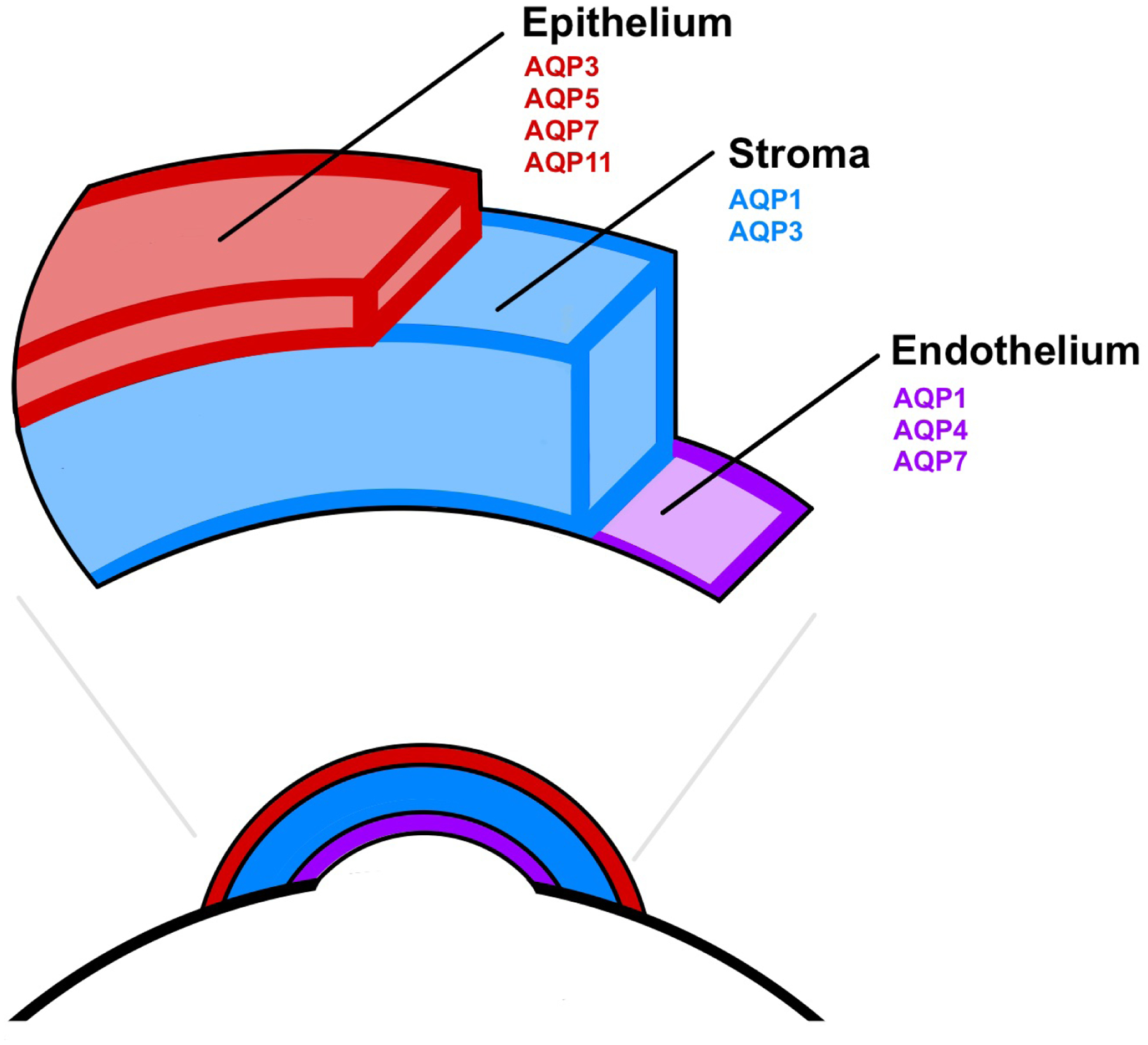

Six of the thirteen AQP isoforms are found in the cornea (AQP1, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 11) (Bogner et al., 2016; Nautscher et al., 2016; Tran et al., 2017; Verkman et al., 2008). The corneal epithelium expresses AQP3, AQP5, AQP7, and AQP11 (Deguchi et al., 2022; Kumari et al., 2018; Tran et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2012). The stroma of the cornea contains AQP1 and AQP3 (Tran et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2012). AQP1, AQP4, and AQP7 are found in the corneal endothelium (Bonanno, 2003; Thiagarajah and Verkman, 2002; Tran et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2012). Figure 1 represents the AQPs expression in the cornea. AQP0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, and 12 mRNA were expressed in rat cornea (Yu et al., 2012). AQP1 is expressed in corneal endothelium and keratocytes in mice and humans (Yu et al., 2012). Rabbit cornea express AQP3, AQP5 (epithelium), and AQP1 (keratinocytes, endothelium) (Bogner et al. 2016). Increased expression of AQP3 was reported in corneal epithelium and AQP4 in corneal endothelium in Fuchs’ dystrophy and bullous keratopathy patients compared with normal subjects (Yu et al., 2012). AQP5 is expressed in human and rabbit corneal epithelium. AQP5 is significantly higher in the tears of Sjogren’s syndrome patients, maybe from the damaged corneal epithelium (Yu et al., 2012).

Figure 1:

Schematic diagram depicting the relative location of AQPs expression in the cornea. The corneal epithelium (red) expresses AQP3, AQP5, AQP7, and AQP11. The stroma (blue) expresses AQP1 and AQP3. Corneal endothelium (purple) expresses AQP1, AQP4, and AQP7.

AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 have been extensively studied in the cornea and thus their basic functions in corneal homeostasis are known though not completely. AQP1, expressed throughout the corneal stroma and endothelium, has been shown to play a crucial role in corneal water transport (Bonanno, 2003; Thiagarajah and Verkman, 2002). The expression of AQP1 in the stroma promotes efficient water efflux into the anterior chamber of the eye (Bonanno, 2003). Endothelial AQP1 expression and function have a minimal role in corneal water efflux under normal conditions; however, the expression and facilitation of water efflux by AQP1 in the endothelium have been shown to play a role during times of edema (Meli et al., 2018). Endothelial AQP1 also has no facilitation of CO2 transport, though it has been seen in other tissues suggesting the primary role of AQP1 in the cornea is solely in stress-induced water efflux (Allnoch et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Corneal keratocytes and endothelial cells express AQP1. AQP1 expression in keratocytes influences their migration to the site of injury in vitro and in vivo mouse models (Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman, 2009). AQP1 plays an important role in the migration of keratocytes in the stroma through stromal ECM and extracellular spaces by squeezing as demonstrated using in vitro and in vivo corneal wound healing models. The deficiency of AQP1 reduces keratocyte migration and reduces keratocytes in the wound area and delays the wound healing process (Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman, 2009). AQP1-deficient mice show a 20% reduction in corneal thickness and prolonged recovery of corneal transparency and corneal thickness (Verman 2006). Similarly, corneal thickness increased in AQP5 null mice (Schey et al., 2014). AQP1 and AQP5 are important regulators of water movement across the corneal epithelium and endothelium. AQP1 plays a role in the extrusion of fluid from the corneal stroma across the endothelial cells and regulates corneal transparency under stress conditions (Verman 2006). AQP1 is important in corneal stromal wound repair (Schey et al. 2014). Further, AQP1 regulates endothelial cell volume and enhances endothelial cell migration through facilitated water transport by lamellipodia in the angiogenesis process (Verman 2006). Thus, AQP1 inhibitors can cause anti-angiogenic activity for therapeutic purpose.

Expression of AQP3 can be seen in corneal epithelium and stroma (Bogner et al., 2016; Verkman et al., 2008). The outer stratified corneal epithelium expresses high levels of AQP3 to facilitate water efflux. Glycerol transport by AQP3 facilitates corneal epithelial and stromal cell proliferation and migration (Banerjee and Sen, 2015). Induced expression of AQP3 in times of osmolar stress increased glycerol permeability resulting in hyperproliferation (Bollag et al., 2020a; Fluhr et al., 2008; Login et al., 2019; Pimpão et al., 2022). AQP3 is implicated in wound healing, corneal epithelial cell proliferation and migration during re-epithelialization and could be dependent on AQP3-associated glycerol transport or some non-transporting role of AQP3 (Levin MH and Verkman AS, 2006). AQP3 deficient mice show delayed corneal re-epithelialization and impaired epithelial proliferation in vivo as compared to wild-type mice. AQP3 deficiency also showed reduced corneal epithelial cell migration in primary cultures in vitro. (Levin MH and Verkman AS, 2006). Corneal keratocytes express AQP1 and synthesize ECM and play an important role in the inflammatory response and wound healing (Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman, 2008).

AQP5 is expressed throughout the corneal epithelia with the most abundant expression in the single-layer basal columnar epithelium (Kumari et al., 2018; Verkman et al., 2008). The expression of AQP5 in the epithelium facilitates efficient water efflux into the exterior of the eye (Verkman et al., 2008). AQP5 has also been shown to hinder cell-cell adhesion via interactions with junctional proteins independently of AQP5-mediated water transport and thus expediting endothelial cellular migration (Login et al., 2021).

AQP4, AQP7, and AQP11 expression dynamics in corneal homeostasis are not yet well understood; however, their function in other tissues can be discussed in the context of corneal homeostasis and wound healing. AQP4 is expressed in the corneal endothelium (Tran et al., 2017). The main function associated with AQP4 in the eye is the regulation of water, the exact mechanism of this regulation requires further investigation; however, there is evidence that AQP4 decreases levels of membrane-associated lateral junctional proteins present in the eye, thus AQP4 may facilitate cellular migration (Login et al., 2019). AQP7 is found in the corneal epithelium and endothelium and is thought to play a role in corneal water efflux similar to endothelial AQP3 function (Sohara et al., 2005; Tran et al., 2017). In addition, AQP7 is postulated to play a similar role to AQP3 in cell proliferation and migration as AQP7 has a similar mechanism of glycerol permeability to that of AQP3 (Falato et al., 2022; Iena and Lebeck, 2018). AQP11, unlike AQP3 and AQP7, is suggested to play a role in stress mitigation through ER uptake of hydrogen peroxide (Ishibashi et al., 2021). The expression of AQP11 in the corneal epithelium, the first layer of corneal defense, suggests that AQP11 facilitates corneal homeostasis through the removal of toxic ROS and subsequent alteration of autophagy and may play a role in corneal wound healing (Tanaka et al., 2016; Tran et al., 2017).

Several animal models were used to investigate the role of AQPs in various animals including mice, rats, and rabbits (Bogner et al., 2016; Rios et al., 2019; Patil et al., 1997). Various types of AQPs deficient/transgenic (upregulation/overexpression and downregulation models) such as deficiency of AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 animals were used to study the role of specific AQPs in the corneas and compared with wild-type animals (Macnamara et al., 2004; Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman 2009; Levin and Verkman 2004; Verkman 2003; Verkman 2006; Liu et al., 2021). Various animal models were used to investigate corneal injury and wound healing, epithelial and endothelial injury, epithelial debridement of corneas, immune cell and keratocyte migration to the site of injury, cell proliferation, corneal thickness and transparency, corneal cell volume changes, angiogenesis, edema, water permeability across corneal cells and the specific AQPs involved in these processes (Rios et al., 2019; Verman 2006; Thiagarajah and Verkman 2002; Yu et al., 2012; Schey et al., 2014; Kumari et al., 2018; Liu et al. 2021; Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman 2009).

4. Wound healing and the role of aquaporins

Wound healing is a multifactorial physiological process to return to homeostasis post-injury. Injuries to the tissue can include but are not limited to trauma, chemical exposure, toxins, extreme temperature, and microbial infections (Guo and DiPietro, 2010). General wound healing involves four distinct stages including coagulation and hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, scar formation and wound remodeling (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, mast cells, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts are pertinent to wound healing (Kamil and Mohan, 2021).

The first phase of wound healing, hemostasis begins immediately after an injury occurs and allows for vasoconstriction and clot formation (Guo and DiPietro, 2010; Maltaneri et al., 2020). Post clot formation the surrounding tissue initiates the second step of wound healing, inflammation, through the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Meli et al., 2018; Wilson, 2020). The innate aspect of the immune response attracts proinflammatory neutrophils and monocytes to the site of injury (da Silva and Soveral, 2021). Monocytes also differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells to aid immune responses (Raziyeva et al., 2021). Inflammation facilitates wound healing through the control of bleeding and prevention of infection through the removal of pathogens, damaged and dead cells by neutrophils and macrophages through phagocytosis. This process is also known to generate ROS (Kamil and Mohan, 2021). Chemokines, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and other factors are released to recruit more innate immune cells to aid in ECM remodeling, cellular proliferation and differentiation, cellular migration, and further inflammation (Bukowiecki et al., 2017; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Once the proliferative formation of new collagen and ECM networks take place, the wound contraction and cell proliferation occur (Kamil and Mohan, 2021). The wound remodeling phase occurs when collagens are reorganized and cells that become obsolete are removed via apoptosis (Wilson et al., 2002).

AQPs are classically known to be key regulators of the inflammatory phase of wound healing (Meli et al., 2018). The expression of AQPs is altered from the homeostatic levels in wound healing to help facilitate the flow of water, glycerol, and other molecules throughout the tissue to expedite the wound-healing process (Prangenberg et al., 2021; Tricarico et al., 2022). AQPs traditionally represent an aspect of inflammatory response events through the facilitation of water influx through increasing cellular hydraulic permeability (Mariajoseph-Antony et al., 2020). The increase in membrane permeability to water and other small molecules respectively into tissues enables the infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes (Mariajoseph-Antony et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2022). Recent studies postulate that AQP plays a substantial role in not only the inflammatory aspect of wound healing but many aspects of wound healing throughout the body (Maltaneri et al., 2020; Tamma et al., 2018; Verkman, 2012). Current research shows high variability between subclasses of AQPs’ facilitation of immunity, for the purpose of this review, the detailed inclusion of specific subclasses will pertain only to those found in the cornea though other subclasses may play some role in wound healing of other tissues (Meli et al., 2018; Yan et al., 2020). The function of AQPs is summarized in Table 2 (Fluhr et al., 2008; Ishibashi et al., 2021; Login et al., 2019; Meli et al., 2018; Pimpão et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2017; Segura-Anaya et al., 2021; Sidhaye et al., 2012; Sohara et al., 2005; Tanaka et al., 2016; Tricarico et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021; Wittekindt and Dietl, 2019).

Table 2.

AQP isoforms and their respective subclass, location in the cornea and postulated role in wound healing.

| AQPs | Subclass | Location(s) | Role in wound healing |

|---|---|---|---|

| AQP1 | Classic | Stroma, Endothelium | Migration |

| AQP3 | AQGP | Epithelium, Stroma | Migration, Proliferation |

| AQP4 | Classic | Endothelium | Migration, Proliferation |

| AQP5 | Classic | Epithelium | Migration, ECM Remodeling |

| AQP7 | AQGP | Epithelium, Endothelium | Migration, Proliferation |

| AQP11 | SAQP | Epithelium | ER Stress Mitigation, Autophagy |

AQP1 expedites the cellular migration of endothelial cells through water influx (Allnoch et al., 2021). The presence of AQP1 pores in the cellular membrane allows for a 5-to-10-fold increase in water intake into the cells (Bonanno, 2003). The influx of water facilitates the formation of the lamellipodium on the leading edge of migratory cells (Loreto and Reggio, 2010; Maltaneri et al., 2020). AQP1-mediated water influx also allows for plasma membrane protrusion and blebbing that facilitates calcium influx needed for cytoskeleton contraction and thus cellular movement (Hayashi et al., 2009). The plasma membrane swelling also creates a pressure-induced space gap from the actin cytoskeleton that allows for polymerization and formation of filopodia in the cells involved in wound healing such as fibroblast (Hayashi et al., 2009; Maltaneri et al., 2020). Angiogenesis, the production of new vasculature, is promoted by AQP-1 through erythropoietin stimulation in endothelial cells (Maltaneri et al., 2020; Shankardas et al., 2010). An inverse correlation between AQP1 expression and membrane-associated junctional protein levels has also been reported (Allnoch et al., 2021; Jorge, 2010). The deficiency of AQP1 leads to the formation of edema by affecting vascular endothelium and intercellular junctions in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) cases (Allnoch et al., 2021). AQP-1 is implicated in endothelial migration (Maltaneri et al., 2020). Migratory facilitation by AQP1 has also been shown recently to influence immune cells, specifically macrophages (da Silva and Soveral, 2021). Dysregulation of AQP1 has also shown further effects on cellular migration with regard to metastasis (Aikman et al., 2018). Breast cancers result in a correlation between AQP1 expression in myoepithelial cells and poor prognosis and cancer progression (Traberg-Nyborg et al., 2022). Expression of migrating cancer cells also shows localization of AQP1 towards the edge of cells that facilitated extravasation and metastasis (Aikman et al., 2018). The over-expression of AQP1 allows for cancer cells to perpetuate the migratory aspects of AQP1 expression further alluding to AQP1 role importance in cellular migration. Similar reports have also been seen in gastrointestinal endothelial cell migration, cerebral edema post-traumatic brain injury, polyuria, and prion diseases (Hayashi et al., 2009; Shi et al., 2019; Thiagarajah and Verkman, 2002; Tran et al., 2010).

The regulation of glycerol transport by AQP3 has been shown to facilitate wound healing through increased cellular proliferation and decreased migration (Arif et al., 2018). Glycerol level increases due to AQP3 enhancement of transport allowing for an influx of fuel for cellular migration and proliferation (Choudhary et al., 2017). The best example of this phenomenon has been seen in sperm progenitor cells as the high levels of both AQP3 (tail) and AQP7 (head) have been shown to facilitate mobility and growth (Schey et al., 2014). AQP3 has also been shown to enhance water loss in the skin in diseases such as atopic dermatitis and general skin dryness (Tricarico et al., 2022). Similarly, AQP3 levels have been shown to increase upon injury to the skin near the site of injury (Fluhr et al., 2008; Prangenberg et al., 2021). Some reports have even suggested that AQP3 can be used to date the time of skin injuries due to their relative prevalence (Prangenberg et al., 2021). Increased levels of plasma membrane-associated lateral junctional proteins have also been shown to correlate with AQP3 levels (Login et al., 2019). The ability of dysregulation and subsequent overexpression of AQP3 in dermal keratinocytes has shown a decrease in cell proliferation and migration associated with various skin diseases such as atopic eczema due to trans-epidermal water loss (Fluhr et al., 2008; Prangenberg et al., 2021). In addition, skin pathologies such as vitiligo have shown decreased levels of AQP3 also induce by decreased levels of cellular adhesion proteins including β-cadherin, γ-catenin, and phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) which results in reduced cellular barrier recovery (Prangenberg et al., 2021). The regulation of these adherent proteins is independent of the AQP3 water transport function as it is regulated by the cytoplasmic tail ends of the AQP. The same phenomena have been seen in Madin-Darby canine kidney cell models as well. Thermal and mechanical skin injuries have also been shown to increase the expression of AQP3 during the wound-healing process (Pimpão et al., 2022). AQP3 facilitates proliferation through decreased migration and increased proliferation facilitates the proliferative phase of wound healing more so than the inflammatory phase suggesting AQPs may play a larger role in wound healing than participation in the inflammatory phase alone. AQP7 elicits a similar response to AQP3 in the regulation of glycerol and facilitation of migration, though the exact impact of AQP7 in wound healing is still a relatively new area of research and thus does not have as extensive information as AQP3; however, knock-out models of proximal tubule cells have shown decreased glycerol reuptake and increased glycerol urine contents suggest a similar mechanism of facilitation (Yang et al., 2022).

AQP5 is shown to play a role in cellular migration through water efflux and decreasing cell-to-cell adhesion through the reduction of adherens and tight junction proteins (Qin and Boron, 2013). The regulation of cellular adhesion by AQP5 is shown to affect the cellular adhesion proteins beta-cadherin, gamma-catenin, and phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) in an antagonist effect to AQP3 (Login et al., 2019; Sidhaye et al., 2012). The opposing effects of AQPs may allude to facilitating different phases of corneal wound healing. The mechanism of water efflux facilitation of cellular migration by AQP5 has been shown to have a similar pattern to that of AQP1 (Login et al., 2021). Unlike AQP1, AP5 has been postulated to elicit an effect on cell-to-cell adhesion through interactions with junctional proteins independently of AQP5-mediated water transport (Login et al., 2021). The ability to alter cellular adhesion allows for a mechanism of multicellular migration that facilitates AQP5 role in metastasis in breast cancer (Li et al., 2018). AQP5 expression correlates with microtubule assembly and stabilization well in respiratory epithelial cells (Sidhaye et al., 2012). The assembly and stabilization of microtubules in the ECM assist the proliferative and remodeling phases of wound healing as both phases involve ECM reorganization (Mohan et al., 2022; Sidhaye et al., 2012). In the proliferative phase, AQP5 role in cellular migration, adhesion, and microtubule assembly suggests a role in the ECM and collagen rebuild tissues laying the groundwork for new cell assembly. In the epithelia, this is known as epithelization (Wilson et al., 2002). AQP5’s role in cellular migration, adhesion, and microtubule assembly suggests a role in epithelization. AQP4 has been shown to play a similar role to AQP1 through water influx and AQP5 through decreasing levels of plasma membrane-associated lateral junction proteins. AQP4 also participates in scar formation through the facilitation of proliferation (Login et al., 2019). The proliferative effects of AQP4 have been shown to aid in cytotoxic swelling in ischemia as well as glial scar formation through the promotion of astrocyte migration and proliferation of post-traumatic brain injury or seizure (Lu et al., 2021).

AQP11 is a SAQP known to facilitate the mitigation of ROS (Ishibashi et al., 2021). The removal of ROS in wound healing is critical as neutrophils and macrophages phagocytosis generate ROS (Tanaka et al., 2016). Under high levels of ROS, oxidative stress, mitochondrial membrane potential can be lost causing mitochondrial dysfunction and thus cellular death (Ishibashi et al., 2021). The removal of ROS allows for mitigation of cellular damage and thus impedes further injury (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). AQP11 knockout models in proximal tubules renal cells have also shown enhanced expression of apoptosis and ER-stress-related caspase genes suggesting inducing increased autophagy in kidney cysts. Expression of AQP11 is thought to inhibit autophagy in homeostasis through mitigation of ER damage thus reducing the need for an autophagic breakdown of misprocessed proteins by the ER in times of stress (Tanaka et al., 2016). Further research may be able to illuminate additional understanding of AQP11 function in wound healing and disease as the exact mechanism of its function in wound healing related to autophagy and ER stress is still unknown.

5. Corneal wound healing

Corneal transparency and avascularity are vital for normal vision. Any injury that hinders corneal transparency can cause vision impairment (Sridhar, 2018). Due to the position of the cornea on the exterior of the eye, it is exposed to a variety of injuries that can lead to disruption of transparency, dysregulated barrier function, and in severe cases blindness (Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015; Uthaisangsook et al., 2002). Injury or disease of the cornea can lead to inflammation, neovascularization, infection, ulceration, and scarring/fibrosis (Akowuah et al., 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Disruption of corneal transparency is the predominant cause of visual impairment worldwide (Wilson, 2020). The avascular nature of the corneal tissue shows a different wound-healing mechanism than the vascularized tissues (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Corneal wound healing is a multifactorial process involving apoptotic and necrotic cell death, migration, proliferation, inflammation, differentiation of corneal cells, and remodeling of the ECM (Akowuah et al., 2021; Kamil and Mohan, 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015).

Corneal wound healing begins with epithelial cell apoptosis or necrosis causing the release of cytokines including interleukin-1 (IL-1), epidermal growth factor (EGF), PDGF, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and bone morphogenic proteins (BMP) 2 and 4 (Akowuah et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015). These Cytokines and growth factors induce activation of transcriptional and migratory aspects of epithelial cells (Liu et al., 2021). If injury to the cornea is minor or mild the epithelium will repair itself and return to its normal state (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Ren et al., 2017). In the event of severe or chronic injury, where there is disruption of the epithelial basement membrane, stromal keratocytes at the injury site will undergo apoptosis via the Fas/Fas ligand pathway and quiescent keratocytes will be activated into fibroblast by the release of IL-1 from the epithelium (Wilson, 2020). The release of TGF-β, IL-1 and PDGF facilitates the maturation of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). SMA induces the formation of fibrotic, contractile myofibroblast from fibroblast that allow for synthesis and excretion of ECM components and facilitators of ECM remodeling in the stroma such as fibronectin, laminin, metalloproteinases, and collagenases (Hayes et al., 2017). Keratocytes will also secrete various growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines that elicit immune and inflammatory responses in the stroma (Akowuah et al., 2021). The inflammatory response allows for the clearing of cellular debris, dead cells, and damaged ECM components by immune cells to reduce potential infection or further scarring (Akowuah et al., 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). The stroma elicits a release of keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) and HGF in response to epithelial IL-1 to induce epithelial cell migration, proliferation, and differentiation (Miyagi et al., 2018). Corneal endothelial cells also release some amounts of IL-1, TGF-β1 and PDGF to facilitate stomal restoration (Kamil and Mohan, 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). If the endothelium is also damaged further injury to the stroma can also occur causing the death of keratocytes in the posterior region (Hayes et al., 2017). In severe cases, complications of endothelium healing may also cause endothelial fibrosis in the retro-corneal membrane (Hayes et al., 2017; Thiagarajah and Verkman, 2002). Once the epithelial basement membrane is regenerated levels of TGF-β1 and PDGF begin to drop allowing for the induction of myofibroblast apoptosis and subsequent repopulation of stromal keratocytes (de Oliveira and Wilson, 2020). The autophagy mechanism also may facilitate the removal of dysfunctional intracellular components to rehabilitate damaged cells to homeostasis. Current research suggests autophagy may aid stromal repair through the reduction of pathological ECM components in stromal fibrosis as well (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015; Wilson, 2020). Due to the lack of angiogenesis in the healthy cornea, this process can be slow leading to an increased risk for complications or infection (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). In the event of the total wound, healing does not occur or is insufficient to prevent infection permanent fibrosis or corneal opacity may occur (Hayes et al., 2017; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Thiagarajah and Verkman, 2002).

Failure to restore the epithelial basement membrane can cause perpetuation of stromal myofibroblast and thus corneal haze or fibrosis (Kamil and Mohan, 2021). Severe corneal injury can also cause neovascularization as the body attempts to elicit steps of wound healing found in other tissues (Akowuah et al., 2021; de Oliveira and Wilson, 2020; Mohan et al., 2022). Angiogenesis occurs in the endothelium of the cornea limbus and is facilitated by cells from the bone marrow (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), TGF-β, PDGF, beta Fibroblast Growth Factor (βFGF) and IL-1 from epithelial, stromal, endothelial, and immune cells facilitated this neovascularization (de Oliveira and Wilson, 2020; Miyagi et al., 2018). The persistence of these new blood vessels can cause chronic corneal edema and corneal thickening (Mohan et al., 2022). The thickening of the cornea and opacity of the new blood vessels can lead to visual impairment (Akowuah et al., 2021; de Oliveira and Wilson, 2020; Miyagi et al., 2018).

AQPs-mediated increased water permeability facilitates the migration of cells to the site of injury during the wound healing phase. Moreover, AQPs-mediated cellular shape and volume change also facilitate the movement of cells through narrow extracellular spaces (Schey et al., 2014). AQPs facilitation of cellular migration, proliferation, ER stress mitigation, apoptosis, wound healing and repair, and autophagy may play a vital role in corneal pathophysiology and homeostasis in vivo and invitro studies (Banerjee and Sen, 2015; Bortner and Cidlowski, 2020; Holm, 2016; Kumari et al., 2018; Levin and Verkman, 2006; Maycock and Marshall, 2014; Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman, 2009). AQP5 plays an important role in corneal epithelial wound healing (Kumari et al., 2018). Altered expression of AQP levels is indicated in corneal cells during corneal wound healing (Mani et al., 2020; Ríos et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022). AQP levels help regulate fluid dynamics in homeostasis and can also help regulate these levels in times of inflammation or swelling associated with corneal wound healing (Meli et al., 2018). In chronic wounds, high levels of inflammatory cytokines can perpetuate high AQPs expression to facilitate higher corneal water content, specifically in the mouse stroma (Akowuah et al., 2021). In down-regulation models, AQP1 and AQP5 have been shown to play a role in corneal endothelial cell migration through extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) signaling pathway in corneal neovascularization using in vitro cultured human corneal endothelial and human corneal epithelial cell lines (Hoffert et al., 2000; Shankardas et al., 2010). The expression of AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 have been shown to be elevated in abrasion and subsequent saltwater immersion of the rabbit cornea (Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, corneal exposure to blast injury has shown elevated levels of AQP1 and AQP5 mRNA in adult male Dutch Belted rabbits (Ríos et al., 2019). Both studies suggest a correlation between corneal injury and AQP expression leading to the postulation of if proven roles of AQP in the wound healing process of other tissues can illude to similar roles in corneal wound healing.

6. Dysregulated aquaporins and their effects

Dysregulation of AQPs has been reported in a variety of pathologies including polycystic kidney disease (AQP11), dry eye disease (DED) (AQP4, AQP5), cerebral edema (AQP1), melanoma (AQP1), vitiligo (AQP3), breast cancer (AQP3, AQP5), endometrial carcinoma (AQP3), Keratoconus (AQP5), diabetic macular edema (AQP4), pancreatic cancer (AQP5), polyuria (AQP7), and astrocytic glial cell scarring (AQP4) (Azad et al., 2021; Burghardt et al., 2003; Edamana et al., 2021; Garfias et al., 2008; Hua et al., 2019; Kenney et al., 2004; Khaled et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018; Traberg-Nyborg et al., 2022; Tran et al., 2010; Yadav et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022). Development of a serum AQP4 autoantibody-based diagnostic testing for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMO) or Devic’s disease has been reported (Wang et al., 2017). The severity of breast cancer prognosis has also been shown to directly correlate to AQP5 levels in metastatic adenocarcinoma of breast tissue epithelium allowing for the postulation that AQP5 increases drug resistance and enhances chemosensitivity in breast cancer (Li et al., 2018). AQPs dysregulation has been shown to disrupt cellular homeostasis through over and under-expression; however, the need to alter AQPs expression may also facilitate some aspects of wound healing (Prangenberg et al., 2021).

Corneal injury and subsequent blindness have become a critical issue globally impacting over 4.9 million individuals around the world (Mohan et al., 2022). Corneal abrasions, chemical burns, ocular disorders, surgical complications, and blast injuries can severely impair the corneal barrier and significantly impact the quality of life (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Ljubimov and Saghizadeh, 2015; Mohan et al., 2022). Terrorist attack-related corneal injuries such as exposure to toxic gas, blast waves, combat blast, and traumatic brain injury are prevalent among veterans, active military personnel, and civilians (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Ríos et al., 2019). These injuries can cause acute and chronic corneal injuries that severely impair visual acuity (Hayes et al., 2017; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Thiagarajah and Verkman, 2002). Effects of traumatic brain injury on ocular function can last from weeks to decades and include corneal disorders such as stromal scarring, DED, reduction in endothelial cell density, bacterial infection of the cornea, and foreign body lodgment in the cornea (Ríos et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2022). Chemical burns can also be prevalent in warfare-related ocular injuries with the use of toxic chemicals such as sulfur mustard (SM), hydrogen sulfide, acrolein, phosgene oxime, chlorine, carbofuran and various other compounds that can severely impair corneal functions (Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Exposure to these agents can cause ocular pathologies such as edema, redness, watering of the eye, itching, abrasion, corneal melting, neovascularization, visual haze, and blindness (Goswami et al., 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022). Reports on corneal blast trauma models have shown edema-related changes in corneal wound manifestation through increased expression of AQP1 and AQP5 (Ríos et al., 2019). Similarly, studies have also shown immersion in salt water post penetrative explosive injury to the cornea caused upregulation of AQP1, AQP3, and AP5 correlating directly with corneal thickening and inflammatory cytokine levels (Wang et al., 2022). AQP3 is implicated in wound healing, corneal epithelial cell proliferation and migration during re-epithelialization and could be dependent on AQP3-associated glycerol transport or some non-transporting role of AQP3 (Levin and Verkman 2006). AQP3 deficient mice show delayed corneal re-epithelialization and impaired epithelial proliferation in vivo as compared to wild-type mice. AQP3 deficiency also showed reduced corneal epithelial cell migration in primary cultures in vitro (Levin and Verkman 2006).

Previous reports and our recent studies suggest irregular AQP mRNA levels (AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5) during acute wound healing post-exposure to the chemical toxin SM (Kamil and Mohan, 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Mohan et al., 2022). Ocular injuries due to SM include acute vision loss, light sensitivity, swelling, pain and severe corneal injury. In the cornea, severe injury can be denoted as mustard gas keratopathy (MGK) (Mohan et al., 2022). MGK includes a variety of symptoms leading to corneal degeneration. In general SM-induced MGK is a result of multiple characteristics of injury including corneal epithelial erosions, increased corneal perforation, epithelial-stromal separation, haze/fibrosis, ulceration, neovascularization; however, sparsity of research when it comes to the molecular mechanism of MGK pathology (Kamil and Mohan, 2021; Naderi et al., 2019). We have recently reported changes in corneal thickness due to SM exposure in both acute and chronic SM-induced MGK. These studies show an acute increase in corneal thickness and decreased ocular thickness in a chronic injury. The acute corneal thickening and edema were postulated to be due to structural changes in the cornea to cause defects in the AQPs function (Kamil and Mohan, 2021; Kempuraj and Mohan, 2022; Mohan et al., 2022). These changes in function could inhibit the ability of the cornea to dehydrate, causing acute edema, and dehydration, which could cause a chronic decrease in corneal thickness. Dysfunction of AQPs in the cornea can lead to loss of osmolar homeostasis and complication in wound healing (Meli et al., 2018). Our recent studies have shown an influx of water in acute corneal wound healing causing corneal thickening (Figure 2) inversely correlates with AQP expression in SM exposure in an in vivo rabbit model. In these experimental models, exposure to SM gas significantly decreased AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 mRNA expression levels on day 3, day 7, and day 14 as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2:

Corneal thickness (µm) in naïve (NT) and SM-exposed treatment groups in vivo rabbit corneas on day 3, day 7, and day14 post SM-exposure (n=6). All rabbits received a target of 200 mg-min/m3 SM vapor exposure for 8 minutes. All the results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons using GraphPad program. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. (*** p < 0.01, naïve control Vs SM treated).

Figure 3:

mRNA levels of AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 normalized to β-actin in naïve (NT) and SM-exposed treatment groups on day 3, day 7, and day14 post SM-exposure in New Zealand White rabbits. Six SM-exposed corneas and six naïve corneas from each group were used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (q-PCR), and each sample was tested in triplicate. All the results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons using the GraphPad Instat 3 program. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant (** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.01, naïve control Vs SM treated).

Unlike puncture wounds, chemical wounds may cause AQPs to denature and thus be degraded by various wound-healing mechanisms (Mohan et al., 2022). The loss of function and subsequent degradation of AQPs could lead to a decrease in expression. Similarly, disruptions of the epithelial barrier, stromal-endothelial connection, and overall homeostasis of the cornea may allow for swelling that is not AQPs regulated (Akowuah et al., 2021; Mohan et al., 2022). It is also worthy noting that at early time points, AQP1 levels were not significantly lower than that of the naïve treatment group; however, AQP3 and AQP5 are shown to have a significant decreased at day 3 and day 7 exposure even though their constitutive expression is relatively the same. Due to the nature of AQP1 in water influx and AQP3 and AQP5 in water efflux, the alteration of this ratio may also play an effect in acute corneal edema post-SM exposure. However, AQP1 expression has been shown to increase in 24 h after corneal stab injury in mice indicating a quick increase immediately after the injury (Verkman As 2008). Another study also reported that AQP1 was increased in keratocytes 24 h after the corneal debridement (Ruiz-Ederra and Verkman 2009).

The results of this pilot study suggest exposure to SM causes dysregulation of AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 through significantly decreased levels of mRNA on day 3, day 7, and day 14; however, the exact mechanism for this dysregulation is not yet understood. Complete loss of AQPs expressing cells can lead to decreased AQPs levels following injuries such as in SM-treated corneas. Our laboratory will continue to explore the mechanism and potential therapeutic treatments for the restoration of AQPs expression. Similarly, further research on the AQPs regulation in the cornea will be conducted to further the understanding of SM exposure to AQPs expression in the cornea. It is possible that AQPs expression remains decreased in chronic corneal injury due to SM and may have other implications in wound healing past the acute stage; this area of research will also be conducted in our lab soon. The dysregulation of AQPs in SM exposure in the cornea may play a role in acute and chronic injuries such as edema, scaring/fibrosis, and blindness; however, the underlying mechanism is not thus far understood.

7. Conclusions

APQs are ubiquitous water channels vital for transport; however, their role in homeostasis is not confined to water regulation as AQPs facilitate a variety of roles throughout the body including the regulation of glycerol, hydrogen peroxide and other small molecules. Each isoform of AQP has a unique function and permeability to help facilitate a specific role in cellular homeostasis. Thus, proper AQPs expression in various conditions is vital in maintaining homeostasis and AQPs dysregulation is implicit in a multitude of pathologies. AQPs are also inherently intertwined with the complex process of wound healing through cellular migration, proliferation, ER stress mitigation, ECM remodeling and autophagy. Current research on AQP’s roles in these cellular processes has been relatively limited to knockout models and subsequently, the mechanism for AQPs regulation of cellular migration, proliferation, stress mitigation and other roles requires additional experimentation, especially in the cornea. The role of AQPs expression and its dynamics during wound healing in the cornea is still not well understood. The expression dynamics of AQPs may vary based on the duration of wound healing, severity and site of the injury in the cornea. The correlation between skin wound healing and corneal wound healing suggests roles seen for AQPs outside of the cornea in wound healing and homeostasis may illude to further understanding of the role of various AQPs in the corneal pathophysiology. Dysregulation of AQPs expression can lead to a variety of corneal impairments and improper wound healing though the mechanism for this is not yet understood. Similarly, little research has been done on the functions of AQP4, AQP7, and AQP11 in the cornea. AQPs are reported in stromal keratocyte function, corneal inflammatory responses, edema, neovascularization, microvessel proliferation, and wound healing process. AQPs facilitate wound healing by enhancing the movement of corneal stromal keratocytes by squeezing through the cells to the wound site. Further, exploration of the possible roles of AQPs may allow for new perceptions on corneal homeostasis and wound healing mechanisms as they have been shown to have effects on other tissues such as kidneys, the brain, and adipose as well as new therapeutic options for corneal blindness. The research studying expression dynamics of AQPs during acute and chronic corneal injuries, functional role of specific AQPs in normal and injured corneas, and modulation of ECM remodeling in stroma by AQPs is required to advance understanding of AQPs in retaining and restoring corneal function.

Highlights.

Aquaporins influence homeostasis and stress responses in ocular tissues after chemical trauma.

Aquaporins modulate cellular migration, proliferation, ER stress, ECM remodeling, and autophagy.

Aquaporin 1,3, 4, 5, 7, and 11 are expressed in the cornea.

Mustard gas exposure to eye affects AQP3 and AQP5 in the cornea

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported by the University of Missouri Ruth M. Kraeuchi Missouri Endowed Chair Ophthalmology Fund (RRM) and in part from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs 1I01BX00357 and IK6BX005646 awards and the NEI/NIH R01EY0343319, R01EY030774, and U01EY031650 grants (RRM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aikman B, de Almeida A, Meier-Menches SM, Casini A, 2018. Aquaporins in cancer development: opportunities for bioinorganic chemistry to contribute novel chemical probes and therapeutic agents. Metallomics 10, 696–712. 10.1039/C8MT00072G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akowuah PK, de La Cruz A, Smith CW, Rumbaut RE, Burns AR, 2021. An Epithelial Abrasion Model for Studying Corneal Wound Healing. J Vis Exp. 10.3791/63112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ala M, Mohammad Jafari R, Hajiabbasi A, Dehpour AR, 2021. Aquaporins and diseases pathogenesis: From trivial to undeniable involvements, a disease-based point of view. J Cell Physiol 236, 6115–6135. 10.1002/JCP.30318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alishahi M, Kamali R, 2019. A novel molecular dynamics study of CO 2 permeation through aquaporin-5. Eur Phys J E Soft Matter 42. 10.1140/EPJE/I2019-11912-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allnoch L, Beythien G, Leitzen E, Becker K, Kaup FJ, Stanelle-Bertram S, Schaumburg B, Mounogou Kouassi N, Beck S, Zickler M, Herder V, Gabriel G, Baumgärtner W, 2021. Vascular Inflammation Is Associated with Loss of Aquaporin 1 Expression on Endothelial Cells and Increased Fluid Leakage in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Golden Syrian Hamsters. Viruses 13. 10.3390/V13040639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif M, Kitchen P, Conner MT, Hill EJ, Nagel D, Bill RM, Dunmore SJ, Armesilla AL, Gross S, Carmichael AR, Conner AC, Brown JE, 2018. Downregulation of aquaporin 3 inhibits cellular proliferation, migration and invasion in the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. Oncol Lett 16, 713–720. 10.3892/OL.2018.8759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assentoft M, Kaptan S, Schneider HP, Deitmer JW, de Groot BL, Macaulay N, 2016. Aquaporin 4 as a NH3 Channel. J Biol Chem 291, 19184–19195. 10.1074/JBC.M116.740217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad AK, Raihan T, Ahmed J, Hakim A, Emon TH, Chowdhury PA, 2021. Human Aquaporins: Functional Diversity and Potential Roles in Infectious and Non-infectious Diseases. Front Genet 12. 10.3389/FGENE.2021.654865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee J, Sen CK, 2015. microRNA and Wound Healing. Adv Exp Med Biol 888, 291–305. 10.1007/978-3-319-22671-2_15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner B, Schroedl F, Trost A, Kaser-Eichberger A, Runge C, Strohmaier C, Motloch KA, Bruckner D, Hauser-Kronberger C, Bauer HC, Reitsamer HA, 2016. Aquaporin expression and localization in the rabbit eye. Exp Eye Res 147, 20–30. 10.1016/J.EXER.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag WB, Aitkens L, White J, Hyndman KA, 2020a. Aquaporin-3 in the epidermis: more than skin deep. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 318, C1144–C1153. 10.1152/AJPCELL.00075.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag WB, Olala LO, Xie D, Lu X, Qin H, Choudhary V, Patel R, Bogorad D, Estes A, Watsky M, 2020b. Dioleoylphosphatidylglycerol Accelerates Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 61. 10.1167/IOVS.61.3.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno JA, 2003. Identity and regulation of ion transport mechanisms in the corneal endothelium. Prog Retin Eye Res 22, 69–94. 10.1016/S1350-9462(02)00059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortner CD, Cidlowski JA, 2020. Ions, the Movement of Water and the Apoptotic Volume Decrease. Front Cell Dev Biol 8. 10.3389/FCELL.2020.611211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, 2017. The Discovery of Water Channels (Aquaporins). Ann Nutr Metab 70 Suppl 1, 37–42. 10.1159/000463061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowiecki A, Hos D, Cursiefen C, Eming SA, 2017. Wound-Healing Studies in Cornea and Skin: Parallels, Differences and Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 18. 10.3390/IJMS18061257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt B, Elkjær ML, Kwon TH, Rácz GZ, Varga G, Steward MC, Nielsen S, 2003. Distribution of aquaporin water channels AQP1 and AQP5 in the ductal system of the human pancreas. Gut 52, 1008–1016. 10.1136/GUT.52.7.1008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamita G, Delporte C, 2021. Involvement of aquaglyceroporins in energy metabolism in health and disease. Biochimie 188, 20–34. 10.1016/J.BIOCHI.2021.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Chen H, Wang C, Yu J, Tao J, Mao J, Shen L, 2022. The Correlation between the Increased Expression of Aquaporins on the Inner Limiting Membrane and the Occurrence of Diabetic Macular Edema. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022. 10.1155/2022/7412208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Choudhary V, Olala LO, Kagha K, Pan Z Chen X, Yang R, Cline A, Helwa I, Marshall L, Kaddour-Djebbar I, McGee-Lawrence ME, Bollag WB, 2017. Regulation of the Glycerol Transporter, Aquaporin-3, by Histone Deacetylase-3 and p53 in Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol 137, 1935–1944. 10.1016/J.JID.2017.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner AC, Bill RM, Conner MT, 2013. An emerging consensus on aquaporin translocation as a regulatory mechanism. Mol Membr Biol 30, 101–112. 10.3109/09687688.2012.743194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva I. v., Soveral G, 2021. Aquaporins in Immune Cells and Inflammation: New Targets for Drug Development. Int J Mol Sci 22, 1–16. 10.3390/IJMS22041845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RE, Kitchen P, Owen DS, Bland C, Marshall L, Conner AC, Bill RM, Conner MT, 2014. Human aquaporins: regulators of transcellular water flow. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840, 1492–1506. 10.1016/J.BBAGEN.2013.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira RC, Wilson SE, 2020. Fibrocytes, Wound Healing, and Corneal Fibrosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 61:28. 10.1167/IOVS.61.2.28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi H, Yamashita T, Hiramoto N, Otsuki Y, Mukai A, Ueno M, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S, Hamuro J, 2022. Intracellular pH affects mitochondrial homeostasis in cultured human corneal endothelial cells prepared for cell injection therapy. Sci Rep 12:6263. 10.1038/S41598-022-10176-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Bermúdez A, Llavanera M, Fernández-Bastit L, Recuero S, Mateo-Otero Y, Bonet S, Barranco I, Fernández-Fuertes B, Yeste M, 2019. Aquaglyceroporins but not orthodox aquaporins are involved in the cryotolerance of pig spermatozoa. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 10. 10.1186/S40104-019-0388-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edamana S, Login FH, Yamada S, Kwon TH, Nejsum LN, 2021. Aquaporin water channels as regulators of cell-cell adhesion proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 320, C771–C777. 10.1152/AJPCELL.00608.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falato M, Chan R, Chen LY, 2022. Aquaglyceroporin AQP7’s affinity for its substrate glycerol: Have we reached convergence in the computed values of glycerol-aquaglyceroporin affinity? RSC Adv 12, 3128–3135. 10.1039/D1RA07367B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluhr JW, Darlenski R, Surber C, 2008. Glycerol and the skin: holistic approach to its origin and functions. Br J Dermatol 159, 23–34. 10.1111/J.1365-2133.2008.08643.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frühbeck G, Catalán V, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Rodríguez A, 2006. Aquaporin-7 and glycerol permeability as novel obesity drug-target pathways. Trends Pharmacol Sci 27, 345–347. 10.1016/J.TIPS.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfias Y, Navas A, Pérez-Cano HJ, Quevedo J, Villalvazo L, Zenteno JC, 2008. Comparative expression analysis of aquaporin-5 (AQP5) in keratoconic and healthy corneas. Mol Vis 14, 756–761. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geistlinger K, Schmidt JDR, Beitz E, 2022. Lactic Acid Permeability of Aquaporin-9 Enables Cytoplasmic Lactate Accumulation via an Ion Trap. Life (Basel) 12. 10.3390/LIFE12010120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giblin JP, Comes N, Strauss O, Gasull X, 2016. Ion Channels in the Eye: Involvement in Ocular Pathologies. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 104, 157–231. 10.1016/BS.APCSB.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami DG, Mishra N, Kant R, Agarwal C, Croutch CR, Enzenauer RW, Petrash MJ, Tewari-Singh N, Agarwal R, 2021. Pathophysiology and inflammatory biomarkers of sulfur mustard-induced corneal injury in rabbits. PLoS One 16. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0258503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, DiPietro LA, 2010. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res 89, 219–229. 10.1177/0022034509359125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S, 2002. Molecular mechanisms of water transport in the eye. Int Rev Cytol 215, 395–431. 10.1016/S0074-7696(02)15016-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Takahashi N, Kurata N, Yamaguchi A, Matsui H, Kato S, Takeuchi K, 2009. Involvement of aquaporin-1 in gastric epithelial cell migration during wound repair. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 386, 483–487. 10.1016/J.BBRC.2009.06.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S, White T, Boote C, Kamma-Lorger CS, Bell J, Sorenson T, Terrill N, Shebanova O, Meek KM, 2017. The structural response of the cornea to changes in stromal hydration. J R Soc Interface 14. 10.1098/RSIF.2017.0062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Yang B, 2019. Aquaporins in Renal Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 20:366. 10.3390/IJMS20020366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffert JD, Leitch V, Agre P, King LS, 2000. Hypertonic induction of aquaporin-5 expression through an ERK-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 275, 9070–9077. 10.1074/JBC.275.12.9070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm A, 2016. Aquaporins in Infection and Inflammation. Linköping University Medical Dissertations 1520. 10.3384/DISS.DIVA-127500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holm A, Magnusson KE, Vikström E, 2016. Pseudomonas aeruginosa N-3-oxo-dodecanoyl-homoserine Lactone Elicits Changes in Cell Volume, Morphology, and AQP9 Characteristics in Macrophages. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6:32. 10.3389/FCIMB.2016.00032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsefield R, Nordén K, Fellert M, Backmark A, Törnroth-Horsefield S, Terwisscha Van Scheltinga AC, Kvassman J, Kjellbom P, Johanson U, Neutze R, 2008. High-resolution x-ray structure of human aquaporin 5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 13327–13332. 10.1073/PNAS.0801466105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Y, Ying X, Qian Y, Liu H, Lan Y, Xie A, Zhu X, 2019. Physiological and pathological impact of AQP1 knockout in mice. Biosci Rep 39. 10.1042/BSR20182303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iena FM, Lebeck J, 2018. Implications of Aquaglyceroporin 7 in Energy Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 19. 10.3390/IJMS19010154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi K, Tanaka Y, Morishita Y, 2021. The role of mammalian superaquaporins inside the cell: An update. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1863. 10.1016/J.BBAMEM.2021.183617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorge F, 2010. Fluid transport across leaky epithelia: central role of the tight junction and supporting role of aquaporins. Physiol Rev 90, 1271–1290. 10.1152/PHYSREV.00025.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamil S, Mohan RR, 2021. Corneal stromal wound healing: Major regulators and therapeutic targets. Ocul Surf 19, 290–306. 10.1016/J.JTOS.2020.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempuraj D, Mohan RR, 2022. Autophagy in Extracellular Matrix and Wound Healing Modulation in the Cornea. Biomedicines 10. 10.3390/BIOMEDICINES10020339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney MC, Atilano SR, Zorapapel N, Holguin B, Gaster RN, Ljubimov A. v., 2004. Altered expression of aquaporins in bullous keratopathy and Fuchs’ dystrophy corneas. J Histochem Cytochem 52, 1341–1350. 10.1177/002215540405201010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled ML, Bykhovskaya Y, Yablonski SER, Li H, Drewry MD, Aboobakar IF, Estes A, Gao XR, Stamer WD, Xu H, Allingham RR, Hauser MA, Rabinowitz YS, Liu Y, 2018. Differential Expression of Coding and Long Noncoding RNAs in Keratoconus-Affected Corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 59, 2717–2728. 10.1167/IOVS.18-24267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YL, Walsh JT, Goldstick TK, Glucksberg MR, 2004. Variation of corneal refractive index with hydration. Phys Med Biol 49, 859–868. 10.1088/0031-9155/49/5/015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen P, Day RE, Salman MM, Conner MT, Bill RM, Conner AC, 2015. Beyond water homeostasis: Diverse functional roles of mammalian aquaporins. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850, 2410–2421. 10.1016/J.BBAGEN.2015.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen P, Salman MM, Halsey AM, Clarke-Bland C, MacDonald JA, Ishida H, Vogel HJ, Almutiri S, Logan A, Kreida S, Al-Jubair T, Winkel Missel J, Gourdon P, Törnroth-Horsefield S, Conner MT, Ahmed Z, Conner AC, Bill RM, 2020. Targeting Aquaporin-4 Subcellular Localization to Treat Central Nervous System Edema. Cell 181, 784–799.e19. 10.1016/J.CELL.2020.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Yun H, Funderburgh ML, Du Y, 2022. Regenerative therapy for the Cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res 87. 10.1016/J.PRETEYERES.2021.101011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari SS, Varadaraj M, Menon AG, Varadaraj K, 2018. Aquaporin 5 promotes corneal wound healing. Exp Eye Res 172, 152–158. 10.1016/J.EXER.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforenza U, Scaffino MF, Gastaldi G, 2013. Aquaporin-10 represents an alternative pathway for glycerol efflux from human adipocytes. PLoS One 8. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0054474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin MH, Verkman AS, 2006. Aquaporin-3-dependent cell migration and proliferation during corneal re-epithelialization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47, 4365–4372. 10.1167/IOVS.06-0335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Pei B, Wang H, Tang C, Zhu W, Jin F, 2018. Effect of AQP-5 silencing by siRNA interference on chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells. Onco Targets Ther 11, 3359–3368. 10.2147/OTT.S160313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XM, Wendu R. le, Yao J, Ren Y, Zhao YX, Cao GF, Qin J, Yan B, 2014. Abnormal glutamate metabolism in the retina of aquaporin 4 (AQP4) knockout mice upon light damage. Neurol Sci 35, 847–853. 10.1007/S10072-013-1610-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Di G, Wang Y, Chong D, Cao X, Chen P, 2021. Aquaporin 5 Facilitates Corneal Epithelial Wound Healing and Nerve Regeneration by Reactivating Akt Signaling Pathway. Am J Pathol 191, 1974–1985. 10.1016/J.AJPATH.2021.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljubimov A. v., Saghizadeh M, 2015. Progress in corneal wound healing. Prog Retin Eye Res 49, 17–45. 10.1016/J.PRETEYERES.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Login FH, Jensen HH, Pedersen GA, Koffman JS, Kwon TH, Parsons M, Nejsum LN, 2019. Aquaporins differentially regulate cell-cell adhesion in MDCK cells. FASEB J 33, 6980–6994. 10.1096/FJ.201802068RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Login FH, Palmfeldt J, Cheah JS, Yamada S, Nejsum LN, 2021. Aquaporin-5 regulation of cell-cell adhesion proteins: an elusive “tail” story. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 320, C282–C292. 10.1152/AJPCELL.00496.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto C, Reggio E, 2010. Aquaporin and vascular diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol 8:105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DC, Zador Z, Yao J, Fazlollahi F, Manley GT, 2021. Aquaporin-4 Reduces Post-Traumatic Seizure Susceptibility by Promoting Astrocytic Glial Scar Formation in Mice. J Neurotrauma 38, 1193–1201. 10.1089/NEU.2011.2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnamara E, Sams G, Smith K, Ambati J, Singh N, Ambati B, 2004. Aquaporin-1 expression is decreased in human and mouse corneal endothelial dysfunction. Mol Vis 10:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira A, Moura TF, Soveral G, 2015. Aquaglyceroporins: implications in adipose biology and obesity. Cell Mol Life Sci 72, 759–771. 10.1007/S00018-014-1773-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltaneri RE, Schiappacasse A, Chamorro ME, Nesse AB, Vittori DC, 2020. Aquaporin-1 plays a key role in erythropoietin-induced endothelial cell migration. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1867. 10.1016/J.BBAMCR.2019.118569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani R, Shobha PS, Thilagavathi S, Prema P, Viswanathan N, Vineet R, Dhanashree R, Angayarkanni N, 2020. Altered mucins and aquaporins indicate dry eye outcome in patients undergoing Vitreo-retinal surgery. PLoS One 15. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0233517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariajoseph-Antony LF, Kannan A, Panneerselvam A, Loganathan C, Shankar EM, Anbarasu K, Prahalathan C, 2020. Role of Aquaporins in Inflammation-a Scientific Curation. Inflammation 43, 1599–1610. 10.1007/S10753-020-01247-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Unger L, Abir-Awan M, Saadallah A, Halsey A, Baklava Z, Conner M, Törnroth-Horsefield S, Greenhill SD, Conner A, Bill RM, Salman MM, Kitchen P, 2022. Molecular mechanisms governing aquaporin relocalisation. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1864. 10.1016/J.BBAMEM.2021.183853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maycock NJR, Marshall J, 2014. Genomics of corneal wound healing: a review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol 92. 10.1111/AOS.12227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek KM, Knupp C, 2015. Corneal structure and transparency. Prog Retin Eye Res 49, 1–16. 10.1016/J.PRETEYERES.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]