Abstract

Background:

Indoor air quality represents a modifiable exposure to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) health. In a randomized controlled trial (CLEAN AIR study), air cleaner assignment had causal effect in improving COPD outcomes. It is unclear, however, what is the treatment effect among those for whom intervention reduced air pollution and whether it was reduction in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) or nitrogen dioxide (NO2) that contributed to such improvement. Because pollution is a posttreatment variable, treatment effect cannot be assessed while controlling for pollution using intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

Objective:

Using principal stratification method, we assess indoor pollutants as the intermediate variable, and determine the causal effect of reducing indoor air pollution on COPD health.

Method:

In randomized controlled trial, former smokers with COPD received either active or placebo HEPA air cleaners and were followed for 6 months. Saint George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) was the primary outcome and secondary measures included SGRQ subscales, COPD assessment test (CAT), dyspnea (mMRC), and breathlessness, cough, and sputum scale (BCSS). Indoor PM2.5 and NO2 were measured. Principal stratification analysis was performed to assess the treatment effect while controlling for pollution reduction.

Results:

Among those showing at least 40% PM2.5 reduction through air cleaners, the intervention showed improvement in respiratory symptoms for the active (vs. placebo), and the size of treatment effect shown for this subgroup was larger than that for the overall sample. In this subgroup, those with active air cleaners (vs. placebo) showed 7.7 points better SGRQ (95%CI: −14.3, −1.1), better CAT (β=−5.5; 95%CI: −9.8, −1.2), mMRC (β=−0.6; 95%CI: −1.1, −0.1), and BCSS (β=−1.8; 95%CI: −3.0, −0.5). Among those showing at least 40% NO2 reduction through air cleaners, there was no intervention difference in outcomes.

Conclusion:

Air cleaners caused clinically significant improvement in respiratory health for individuals with COPD through reduction in indoor PM2.5.

Trial registration

Keywords: Principal stratification, COPD, particulate matter, environment, air cleaners, randomized controlled trial

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is attributable to the aggregate burden of toxic gases and particles and is a leading cause of death (1, 2). Patients with COPD suffer high morbidity, including poor quality of life. Clinicians have limited intervention options for these patients. International COPD guidelines (GOLD guidelines) (3) emphasize non-pharmacological interventions to improve health; however, limited data on appropriate and effective interventions remains a barrier. Indoor air quality represents one particularly important modifiable exposure (4, 5) and in a recently published randomized controlled trial (CLEAN AIR study) (6), we showed that placement of two portable air cleaners with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) and carbon filters in homes of former smokers with COPD significantly reduced in-home fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations. Furthermore, individuals in the active air cleaner arm had a trend towards improved respiratory specific quality of life and reported a greater improvement in respiratory symptoms. However, not all active group members experienced pollution reduction, and, even among those who experienced the reduction, the magnitudes varied across participants, with some experiencing only small reduction while others more substantial; at the same time, some placebo members—albeit few, despite having placebo air cleaners, experienced pollution reduction of varying magnitudes. As such, due to heterogeneity in pollution reduction, we are limited in our capacity to draw conclusions with regards to the treatment effect on those for whom air cleaners successfully reduced indoor pollution and whether it was the reduction in PM2.5 or NO2 that contributed to such improvement. At the same time, because pollution reduction is itself determined by intervention—that is, pollution reduction is a posttreatment variable— one would not be able to assess treatment effect while controlling for pollution reduction using the conventional approach, such as intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (7); the estimates of treatment effect in such analysis would be biased because participants in active and placebo groups can no longer be considered exchangeable (or identical except for treatment assignment). Principal stratification method is a method relatively seldom applied in environmental trial studies but specifically designed to address these issues (7).

Developing a better understanding of the factors and specific pollutants that mediate the effects of an environmental intervention on COPD is important for identifying a causal role for indoor pollutants in COPD morbidity and for understanding how much improvement in health could be obtained through an effective intervention. Furthermore, it is important to understand which exposure reduction is most associated with health benefits in order to optimize future environmental interventions. Whereas the original study estimated the causal effect of air cleaner assignment on respiratory health, in this study we use the method of principal stratification (7) using indoor pollutant reduction as an intermediate variable, to identify the causal effect of reducing air pollution on respiratory health.

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design and Participant Characterization

The CLEAN AIR study was a double-blind randomized controlled trial among former smokers age ≥ 40 years with moderate-severe COPD (6). Participants were randomized into two groups (clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02236858): 1) active group receiving air cleaners with internal HEPA and carbon filters for reducing PM2.5 and NO2, respectively; 2) placebo group receiving air cleaners without any filters but with similar appearance and overall characteristics (e.g., noise). Each participant received two air cleaners, with one placed in the bedroom and the other in the room the participant spent most waking time (usually a living room). The intervention lasted six months, with pollution and respiratory symptom data collected at baseline and one week, three- and six months post intervention. Participant’s demographics, smoking history, comorbid diseases, and medication use were assessed by trained staff. More details on the study population and clinical/environmental assessment, including pollutant measurement methods, can be found in the main study (6). All participants submitted written informed consent, and the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutional Review Board approved the protocol (NA_00085617).

2.2. Respiratory Outcomes

The continuous outcomes considered in the original study were the change in respiratory symptoms between baseline (pre-randomization) and 6 month (post-randomization). The primary outcome was St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (8). The secondary outcomes were SGRQ subscales, COPD Assessment Test (CAT) (9), modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (10), and the Breathless, Cough, and Sputum Scale (BCSS) (11). Six-minute-walk-distance, which had a smaller number of observations, was dropped from the current analysis due to the number of parameters needed to be estimated in principal stratification analysis. Non-continuous outcomes were not considered due to complexity in modeling.

2.3. Indoor Pollutants

The intermediate variable was the reduction in indoor pollution between baseline and 6 months. The primary pollutant exposure was PM2.5 while the secondary was NO2. Each pollutant was analyzed separately. The detailed sampling and monitoring procedure of indoor air quality assessment is reported elsewhere (12).

2.4. Principal Stratification

Principal stratification analysis falls under counterfactual modeling framework in which causal effects are estimated within unobserved (or latent) subgroups or principal strata defined by potential levels of intermediate variable under treatment (7). See Supplementary Materials for more details on principal stratification method. In this study, the sample consisted of three subgroups: 1) Cleaner-under-treatment, 2) Always-reduced, 3) Never-reduced. Following the terminology used by Peng and his colleagues (13), the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum consisted of participants for whom pollution reduction was achieved only through intervention. The Always-reduced stratum consisted of participants who experienced pollution reduction regardless of air cleaner assignment. The Never-reduced stratum consisted of participants for whom pollution reduction was not achieved regardless of air cleaner assignment. The primary analysis of this study was to estimate the effect of air cleaners on respiratory health among those who experienced PM2.5 reduction only through intervention—that is, among those in the “Cleaner-under-treatment” stratum.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To assess the effect of air cleaner on COPD outcomes through reduction in indoor pollution, we performed principal stratification analysis and estimated the changes in outcomes within the latent subgroup for whom pollution reduction was achieved only through intervention—i.e., the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum. The stratum-specific treatment effect for the Always-reduced and Never-reduced strata were also assessed.

2.5.1. Pollution Reduction Definition

The reduction in pollution was defined as at least 40% decline in concentration between baseline and 6 month and “non-reduction” otherwise. This cut-off level is the reduction level frequently shown across air filtration intervention studies (14, 15); it also ensured an adequate membership probability to the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum, which was the principal stratum of interest. As sensitivity analysis, we additionally considered a 30% cut-off. As secondary sensitivity analysis, we explored treatment effect on our primary outcome while defining pollution reduction in terms of the absolute change in PM2.5 by identifying those whose PM2.5 level fell below the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended level of 5μg/m3 (that is, those whose PM2.5 level was above 5μg/m3 at baseline but fell below 5μg/m3 at 6 month), as well as other thresholds where data permitted.

2.5.2. Analytical Model

Though simultaneously run as a single model, the analytic model for principal stratification method can be construed as consisting of two parts: 1) stratum-membership model and 2) outcome model (see Supplementary Material for technical detail). Because we assume our sample to consists of distinct subgroups in terms of pollution reduction in response to treatment assignment (i.e., Cleaner-under-treatment; Always-reduced; Never-reduced), finite mixture modeling was used (16). This approach assumes a population to consists of unobserved finite and mutually exclusive subpopulations, allowing classification of study subjects into latent subgroups and is flexible in allowing various regression modeling under the assumption of heterogeneous population. The outcome model and the stratum-membership model described above were run simultaneously using finite mixture modeling, using maximum likelihood to estimate the parameters (16, 17) (see Supplementary Materials for detail).

2.5.2.1. Stratum-Membership Model

The stratum membership model assessed the probabilities of latent strata membership—i.e., how likely is a participant to belong to a particular stratum—and the baseline characteristics that are associated with these probabilities. To assess, multinomial logistic regression was run using the principal strata as the dependent variable and baseline participant characteristics, including indoor pollutant assessment, as the predictors; several characteristics were selected as predictors of stratum membership, including individual educational attainment, baseline medication use, and baseline indoor PM2.5 and NO2 levels. In the analysis using NO2 in defining pollution reduction, the covariates selected were gender, smoking pack-years, time since quit smoking, and baseline indoor PM2.5 and NO2 levels. The predictors were chosen using a likelihood ratio test comparing the overall model-fit for primary outcome with and without the candidate predictors.

2.5.2.2. Outcome Model

The outcome model assessed the stratum-specific intervention difference in the change in COPD outcome score between baseline and 6 month—that is, the “treatment effect”. The model followed ANCOVA approach, in which the change in outcome score between baseline and 6 month was regressed on treatment assignment (1=Active HEPA filter air cleaner; 0=Placebo air cleaner) and baseline outcome score, additionally adjusted by baseline covariates—race, medication use, season, area deprivation index, and comorbidities. The covariates were the same set of covariates used in the original study and were selected based on the evidence of treatment imbalance and/or the covariate’s prognostic association with the primary outcome. The model generated three sets of parameter estimates, including those which corresponding to the three stratum-specific treatment effect; the estimates for covariates were restricted to be invariant across strata. In sensitivity analyses, we incorporated the exclusion restriction assumption, constraining the treatment effects for the Always-reduced and Never-reduced stratum to each zero.

All analyses were performed using STATA, version 15.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). STATA’s generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) package was used to perform principal stratification analysis. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

3. Results

Of the 94 individuals completing study and included in the original CLEAN AIR study (6), 12 were missing indoor PM2.5 measurements in baseline and/or 6th month and were excluded from the current analysis. The participant characteristics of the original sample and the subset for this analysis were similar, with generally balanced characteristics between active and placebo groups at baseline, including respiratory symptoms and GOLD stage distributions (Table S4). As was the case in the original sample (6), participants in active group (vs. placebo) were somewhat more likely to have been white, less likely to have used controller medication and had slightly higher number of comorbidities at baseline. On average, participants in our analytic sample spent more than two-thirds of their time indoor - inside the house where air cleaners were placed, with the mean (SD) hours spent indoor per day of 17.7 (4.3) hours, with no difference between the intervention groups (P=0.10). More detailed description of the study population can be found in Hansel et al. (6).

3.1. Principal Stratification Analysis with PM2.5 as Exposure

As shown in the original report (6), the median (IQR) PM2.5 concentration level at baseline was 10.6 μg/m3 (7.3 to 26.1), and between baseline and 6 month, in adjusted analyses, PM2.5 on average declined by 53.5% in the active group (, P<0.001) while no change in the placebo group was observed (, P=0.19). In current unadjusted analyses, 29 out of 49 participants in the active group (59%) showed at least 40% reduction, while 6 placebo participants also showed the similar magnitudes of decline in PM2.5. Analogously, 39 out of 45 participants in the placebo group showed less than 40% decline in PM2.5, while 20 active group (41%) also showed reductions less than 40%.

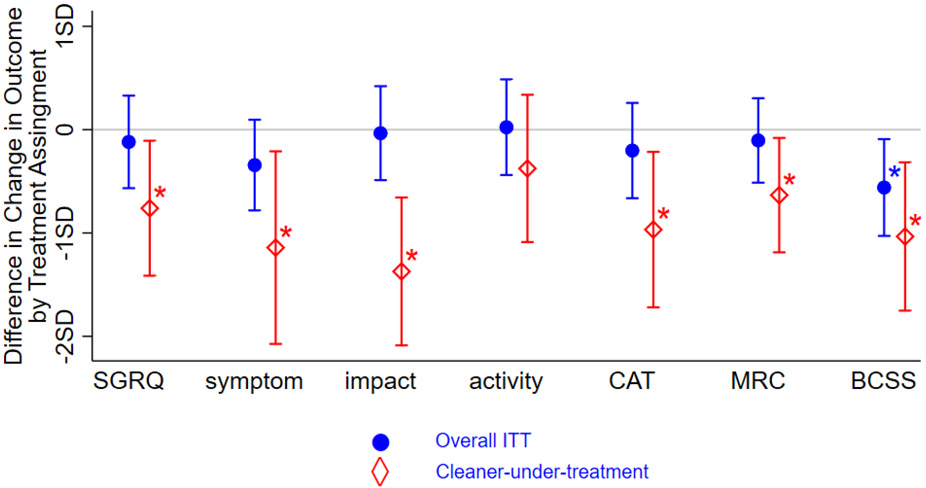

In Figure 1, the treatment effect using the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis from the original study is compared against the stratum-specific treatment effect for the Cleaner-under-treatment using the principal stratification analysis. The point estimate and 95% confidence interval for the intervention difference—standardized—in the change in respiratory outcome score between baseline and 6 months for the overall sample based on the ITT analysis are compared against those of the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum based on the principal stratification analysis. Across all outcomes, the effect size for the Cleaner-under-treatment group tended to be greater than that for the overall intention-to-treat. For the Cleaner-under-treatment, the active group on average showed a change in SGRQ score that was 7.7 points lower (or better) than did placebo group (P=0.022), 21.8 points better SGRQ symptom score (P=0.016), 15.5 points better SGRQ impact score (P<0.001), 5.5 points better CAT score (P=0.012), 0.61 points better mMRC score (P=0.025), and 1.8 points better BCSS score (P=0.005). There was no intervention difference in SGRQ activity score for the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum (Table 1; shows the effect sizes in natural scale).

Figure 1. Intervention Difference in the Change in Outcome Scores: Overall Intention-to-Treat (ITT) vs. Cleaner-under-Treatment Principal Stratum.

Note: The effect sizes are expressed in standard deviation, and stars (*) represent statistical significance. The blue (circle) shows point estimates and 95% confidence intervals based on intention-to-treat analysis using ANCOVA approach, regressing the change in outcome score (between 6th month and baseline) on treatment assignment with baseline score as a covariate and additionally adjusted by baseline covariates, race, comorbidity, medication use, season, and neighborhood disadvantage (Area Deprivation Index). The estimates represent the treatment assignment difference in the change in COPD severity for the overall sample, and the stars represent statistical significance (P<0.05). The red (diamond) shows point estimates and 95% confidence intervals based on principal stratification analysis, using ANCOVA approach for the outcome model and logistic regression for the stratum-membership model, with both models run simultaneously using finite mixture modeling. The outcome model is adjusted by baseline outcome score, race, comorbidity, medication use, season, and neighborhood disadvantage (Area Deprivation Index); and the stratum-membership model is adjusted by baseline PM2.5, NO2, educational attainment, and medication use. The estimates represent the treatment assignment difference in the change in COPD severity for the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum, which consists of participants whose PM2.5 would have declined by at least 40% only through air cleaner intervention; the stars represent statistical significance (P<0.05).

Table 1.

Difference in the Change in Outcome Scores between Active and Placebo: Overall Intention-to-Treat (ITT) vs. Cleaner-under-treatment Stratum

| Overall Intention-to-Treat (ITT)a | Cleaner-under-treatmentb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Difference in Outcome Score between Active & Placebo (95% CI) |

P-value | Estimated Difference in Outcome Score between Active & Placebo (95% CI) |

P-value | |||

| SGRQ | −1.6 | (−5.9, 2.6) | 0.451 | −7.7 | (−14.3, −1.1) | 0.022 |

| Symptom | −7.9 | (−15.3, −0.5) | 0.037 | −21.8 | (−39.5, −4.0) | 0.016 |

| Impact | −1.0 | (−5.8, 3.9) | 0.690 | −15.5 | (−23.5, −7.4) | 0.000 |

| Activity | 0.3 | (−5.3, 5.8) | 0.922 | −4.7 | (−13.6, 4.2) | 0.302 |

| CAT | −0.5 | (−3.0, 2.1) | 0.723 | −5.5 | (−9.8, −1.2) | 0.012 |

| mMRC | −0.2 | (−0.5, 0.2) | 0.394 | −0.6 | (−1.1, −0.1) | 0.025 |

| BCSS | −0.9 | (−1.6, −0.2) | 0.017 | −1.8 | (−3.0, −0.5) | 0.005 |

Note: SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (on a scale of 0 to 100, in which 0 is the best quality-of-life score and 100 is the worst), consisting of a total score and three subscales; CAT = COPD Assessment Test (on a scale of 0 to 40, in wich higher score denotes more severe impact of COPD on individual’s life); mMRC = modified Medical Research Council (on a categorial scale of 1 to 5; higher scores indicate more limitation on daily activities due to breathlessness); BCSS = Breathlessness, Cough, and Sputum Scale (on a 5-point scale from 0 [no symptoms] to 4 [severe symptoms] rating breathlessness, cough, and sputum).

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are based on intention-to-treat analysis using ANCOVA approach, regressing the change in outcome score (between 6th month and baseline) on treatment assignment with baseline score as a covariate and additionally adjusted by baseline covariates, race, comorbidity, medication use, season, and neighborhood disadvantage (Area Deprivation Index). The estimates and p-values represent the treatment assignment difference in the change in COPD severity for the overall sample and their statistical significance.

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are based on principal stratification analysis, using ANCOVA approach for the outcome model and logistic regression for the stratum-membership model, with both models run simultaneously using finite mixture modeling. The outcome model is adjusted by baseline outcome score, race, comorbidity, medication use, season, and neighborhood disadvantage (Area Deprivation Index); and the stratum-membership model is adjusted by baseline PM2.5, NO2. educational attainment, and medication use. The estimates and p-values represent the treatment assignment difference in the change in COPD severity for the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum, which consists of participants whose PM2.5 would have declined by at least 40% through air cleaner intervention and by no other means.

When incorporating the exclusion restriction assumption in the main model (i.e., constraining the treatment effect of the Always-reduced and Never-reduced strata to be zero), the results for the Cleaner-under-treatment group generally remained similar (Figure S1, Table S2). When using the “30%” cut-off level for defining PM2.5 reduction, the intervention difference in the change in total SGRQ and CAT scores were no longer statistically significant, with more uncertainty and smaller effect size respectively than when using the 40% cut-off; otherwise, the results remained similar (Figure SI, Table S2).

For the other two principal strata (Always-reduced and Never-reduced), no effects of treatment assignment were found in any outcomes except for SGRQ impact score within the Never-reduced stratum (Figure S2). Within the Never-reduced, the participants in active group saw a change in SGRQ impact score that was higher (worse) than did placebo (β=10.8, P<0.001). Similar trend of worse outcomes for active group (vs. placebo) were shown for several remaining outcomes within the Never-reduced stratum, but these associations did not reach statistical significance.

In terms of participants’ stratum membership, participants in the Always-reduced stratum tended to report higher baseline PM2.5 concentration, higher educational attainment, and lower likelihood of using controller medication than did participants in the Never-reduced stratum. On the other hand, the participants in the Cleaner-under-treatment tended to report lower NO2 concentration at baseline than did participants in the Never-reduced stratum. The probability of stratum membership ranged slightly differently across outcome models but generally similar. For example, for our primary outcome (SGRQ) model, the average probability of participants’ belonging to Cleaner-under-treatment was 0.44, while belonging to Always-reduced was 0.16 and to Never-reduced 0.40. With “30%” as the cut-off for defining PM2.5 reduction, the average probability of belonging to the Always-reduced stratum increased to 0.37, while the probability of belonging to the other two strata each decreased: from 0.44 to 0.26 for the Cleaner-under-treatment membership, from 0.40 to 0.36 for the Never-reduced membership.

In the secondary sensitivity analysis, defining pollution reduction as those whose PM2.5 level fell below the WHO-recommended level of 5μg/m3, the results for our primary outcome, SGRQ, remained largely similar to that of using the 30-40% reduction definitions, with slightly larger treatment effect sizes but also greater uncertainties in the parameter estimates for the cleaner-under-treatment stratum (Table S3, Figure S4). When using a higher threshold level, such as 12μg/m3, there was no longer a trend for treatment effect for the cleaner-under-treatment (Table S3, Figure S4), which could partly be due to the fact that more than half of the participants in our sample were living in homes with PM2.5 lower than 12μg/m3 at baseline and thus unable to be defined as cleaner-under-treatment despite potentially having a meaningful PM2.5 reduction through intervention; this was reflected in a very low average probability for cleaner-under-treatment stratum membership of 0.08 when using a threshold of 12μg/m3 (in comparison to 0.44 when using the 40% reduction definition or 0.19 when using 5μg/m3 threshold). There was no treatment effect for Always-reduced or Never-reduced in any of the thresholds explored (table not shown).

3.2. Principal Stratification Analysis with NO2 as Exposure

93 out of 94 individuals included the original CLEAN AIR analysis had NO2 measurement. As shown in the original study (6), the median (IQR) NO2 concentration level was 7.7 ppb (2.5 to 14.5) at baseline, and between baseline and 6 month, in adjusted analyses, NO2 declined on average by 28.0% in the active group (, P=0.001) but remained flat in the placebo group (, P=0.62). In the current unadjusted analyses, more than a third of the participants in the active group (23 out of 55) showed NO2 decline of 40% or more, while little more than a quarter of the placebo group (12 out of 42) also showed at least 40% reduction in NO2.

In the main principal stratification analysis using NO2 as the exposure of interest, we found no consistent effect of air cleaner assignment in any outcomes (Figure S3). The results remained similar when using the 30% cut-off for defining NO2 reduction, as well as when incorporating the exclusion restriction assumption (Figure S3). For mMRC, there was suggestion of treatment effect in the unexpected direction, but the finding was isolated and without consistent evidence from the rest of the outcomes. The principal stratification analysis failed to generate reliable optimal solution for SGRQ activity, as the algorithm either failed to converge completely or converged less than 10% of the time across the main and sensitivity models.

In terms of participants’ stratum membership, participants in the Always-reduced stratum and Cleaner-under-treatment tended to report higher baseline NO2 than did participants in the Never-reduced stratum. Also, compared to the participants in the Never-reduced stratum, participants in the Always-reduced stratum tended to be more males and the participants in the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum tended have quit smoking more recently. The probability of stratum membership ranged slightly differently across outcome models but generally similar. For example, for our primary outcome model, the average probability of participants’ belonging to Cleaner-under-treatment was 0.23, while belonging to Always-reduced was 0.20 and to Never-reduced 0.57. With “30%” as the cut-off for defining NO2 reduction, the average membership probabilities remained similar to that of the 40% cut-off: 0.24 for Cleaner-under-treatment, 0.21 for Always-reduced, and 0.55 for Never-reduced.

4. Discussion

We used a principal stratification approach to analyze data from a randomized environmental intervention study of former smokers with COPD to estimate the respiratory health benefit of reducing indoor air pollution. Among the subgroup who experienced at least 30-40% reduction in indoor PM2.5 concentrations only though air cleaners (i.e., the Cleaner-under-treatment), the intervention results in a meaningful improvement in respiratory-specific quality of life and respiratory symptoms; furthermore, this subgroup showed a larger improvement in respiratory symptoms than did the overall participants using intention-to-treat analysis. For those who did not experience PM2.5 reduction through air cleaners (i.e., the Always-reduced and Never-reduced), there was no health improvement. Among the subgroup who experienced at least 30-40% reduction in indoor NO2 through air cleaners (i.e., the Cleaner-under-treatment), there was no improvement in respiratory symptoms. These results suggest that PM2.5, rather than NO2 reduction, is likely responsible for the health benefits of a portable air cleaner intervention, including both HEPA and carbon filters, and supports a causal role for reducing indoor PM2.5 and improving respiratory symptoms in COPD.

Although environmental intervention studies are often designed with a premise for causal mechanism in which the intervention is presumed to impact an outcome through its effect on an intermediate variable, these premises are often left uninvestigated due to the fact that intermediate variables are either unobserved or, if observed, are by definition posttreatment variables and uncontrolled. In the case of an observed intermediate variable, any comparisons of outcome when conditioning on such a variable would suffer from potential confounding because participants can no longer be assumed randomized across treatment groups when conditioning on a posttreatment variable. For this reason, trial studies sometimes present two sets of results to address the questions on causal mechanism: the treatment effect on the main outcomes and the treatment effect on the intermediate outcomes, with the correlations between the two sets of outcomes either assumed or tested (6, 18, 19). Such approach, though informative, loses the benefit of randomization scheme, being subject to confounding, and the approach does not inform on the specific size and direction of treatment effect for the subpopulation that might be of special interest: those for whom treatment effect on intermediate variable is as intended or hypothesized. In cases where the treatment effect on intermediate variable is less than intended, the intention-to-treat effect on the primary outcomes will likely be underestimated in comparison to that which would have been obtained if the effect on the intermediate was as intended (20). This could in some case lead researchers to an erroneous conclusion with regards to the purported hypothesis of the study.

The current analysis uses the counterfactual framework in conducting principal stratification analysis (7, 13) to partition the sample into principal strata defined by their pollutant levels under different treatment assignments and to estimate the effect of the treatment assignment within these principal strata. This is accomplished to estimate the treatment effect on those participants for whom the air cleaner intervention would have been effective in reducing the pollutant levels. For the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum defined by a 40% cut-off for reduction in PM2.5, the active group on average showed a statistically significant change in SGRQ score that was 7.7 points lower (or better) than did placebo group. This demonstrates a larger effect on respiratory specific quality of life for the air cleaner compared with the overall intention-to-treat effect that was a non-significant difference in SGRQ score. Furthermore, in the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum, the active group on average showed similarly large improvements in respiratory symptoms as measured by CAT (ß = − 5.5), mMRC (ß = − 0.6) and BCSS (ß = − 1.8) scores. These effect sizes for SGRQ and CAT are substantially larger than the minimally clinical important difference (MCID) of 4 and 2, respectively for these instruments; and is comparable or exceeds the effect sizes achieved in some of the medication intervention trials. For example, in randomized controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of combining tiotropium with salmeterol or fluticasone-salmeterol, the study found maximal treatment difference of 4.1 points in SGRQ between the experimental group and placebo over 1-year study period (21). In another randomized controlled study, researchers found 6.3 points difference in SGRQ improvement for those taking nandrolone decanoate in comparison to the placebo group, though the difference did not reach statistical significance (22). Additionally, the difference in BCSS score reflects a substantial symptom difference between groups, given the MCID of BCSS is as low as 0.3 (11). When using a “30%” cut-off level for defining the PM2.5 reduction, the group difference for SGRQ and CAT score were no longer statistically significant. These results suggest that a target of at least 40% reduction in PM2.5 may be required to confer a health benefit. The results remained largely similar for our primary outcome when defining pollution reduction by an absolute decline in PM2.5 below the WHO recommended level of 5μg/m3; but at the higher threshold levels, there were no longer trends for treatment effect for the cleaner-under-treatment, suggesting for samples with relatively low baseline PM2.5 as ours, the threshold may have to be lowered if using the absolute change as a definition in place of percent change.

Not surprisingly, the subgroups for whom the intervention did not make any difference in pollutant reduction (i.e., the Always-reduced and Never-reduced) did not show any health benefits from the trial. However, the Never-reduced subgroup (i.e., those whose PM2.5 would not have declined regardless of air cleaner assignment) showed some directional trend towards worse outcomes for active group in comparison to the placebo. One possible reason for such a trend might be that, among those for whom PM2.5 would have never declined, the unmeasured factors or sources of PM2.5 might have been greater for the active group than for the placebo – so as to offset the effectiveness of active air cleaners to reduce PM2.5 – and that these unobserved sources of PM2.5 might have had some impact on the relative health difference between the two groups (presumably, through a pathway other than PM2.5 itself). This is conjecture, and further studies are needed for better understanding.

The portable air cleaners used in this environmental intervention study included a charcoal filter (23) in addition to the HEPA filter, which is capable of removing gaseous species such as NO2. Indeed, in the overall CLEAN AIR study there was a 24% reduction in NO2 concentrations at six months in the arm that received active compared with placebo air cleaners. The current results show that the Cleaner-under-treatment stratum did not show a statistically significant improvement in respiratory-specific quality of life or symptoms for those who achieved at least 30-40% reduction in NO2 by intervention. These results suggest the improvement in respiratory morbidity achieved by the portable air cleaner intervention in this study is likely attributable to the PM2.5 rather than NO2 reduction.

There are a number of limitations to our study. First, those who would have experienced at least 30-40% reduction in PM2.5 might have concomitantly experienced a change in other factor(s), such as other unmeasured gaseous pollutants, that are unobserved yet responsible for improvement in respiratory symptoms. We attempted to minimize such problems by adjusting for several covariates, including participant’s baseline disease severity, but the possibility of confounding still exists. Similarly, it is also possible that changes in outdoor pollutant levels could have impacted indoor PM2.5 reduction and thereby participant’s stratum classification. Though we did not have participant-specific outdoor PM2.5 data, when using the secondary data from Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—matching the ambient PM2.5 data from the monitoring sites that are nearest to a participant’s home at the time closest to his/her study visit-- and adjusting our principal stratification model by EPA ambient PM, the results remained robust (table not shown). Second, the dichotomization of pollutant reduction might over-simplify what is more complex story when using continuous pollutant reduction. However, given the relatively small sample size of this study and the degree of complexity required to model the pollutant reduction as continuous, we believed the simpler approach was reasonable, even if it resulted in less granularity in our findings. Moreover, a 40% reduction in PM2.5 has been shown to be around the level that prior HEPA filter intervention studies have frequently reported achieving (14, 15). Third, the finite mixture modeling, which we use in our analysis, can sometimes return local maxima as its optimization solution for the model’s parameter estimates rather than global (16), and hence we used multiple starting values and checked the replicability of the solution, as well as comparing the results to its neighboring solutions; but, there still exists a possibility for local solutions for some of our parameter estimates. Fourth, the current analysis lost 12 participants from the original analysis due to missing PM2.5 data. Given that the treatment balance in participant characteristics between the current sample and the original sample remained similar, it is unlikely that the loss would have impacted the validity of our findings, but the loss would have impacted the power for our analysis, as well as potentially the generalizability of the finding. Lastly, because of relatively small sample size and the nature of the study design (using PM2.5 data at two time points that are six months apart to determine long-term average trend in indoor PM2.5), mitigating measurement error in indoor pollutant exposure is especially important. To this effect, our study monitored air sampling continuously for approximately one week at each time point and used the average weekly concentration to represent each study visit’s PM2.5 concentration level.

5. Conclusion

In summary, these results suggest that in-home PM2.5 reduction is likely responsible for the health benefits of a portable air cleaner intervention in patients with COPD. Further, a 40% reduction in PM2.5 concentrations is likely needed to obtain clinically significant improvements in respiratory symptoms. The majority (59%), but not all participants in the active treatment arm, showed at least 40% reduction in PM2.5, therefore strategies aiming to improve efficacy and adherence of air cleaner interventions are needed to optimize benefit. This study supports a causal role for reducing indoor PM2.5 and improving respiratory symptoms in COPD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Intention-to-treat analysis is biased when controlling for posttreatment variables.

Principal stratification method properly controls for posttreatment variables.

Air cleaners improve COPD health by reducing indoor PM2.5.

Reducing indoor NO2 by air cleaners has negligible impact on COPD health.

Acknowledgement

The Clinical Trial of Air Cleaners to Improve Indoor Air Quality and COPD Health (CLEAN AIR) was supported by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant [R01ES022607]. The authors thank Austin Air Cleaners for the donation of air cleaners used in this trial. The company did not have any input on study design, analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Meredith McCormack reports financial support was provided by Aridis. Meredith McCormack reports financial support was provided by GlaxoSmithKline. Meredith McCormack reports financial support was provided by Celgene. Roger Peng reports financial support was provided by Health Effects Institute. Nadia Hansel reports financial support was provided by COPD Foundation. Nadia Hansel reports financial support was provided by AstraZeneca. Nadia Hansel reports financial support was provided by GlaxoSmithKline. Nadia Hansel reports financial support was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim. Nadia Hansel reports financial support was provided by Mylan.

List of Abbreviations

- SGRQ

St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

- CAT

COPD Assessment Test

- mMRC

modified Medical Research Council

- BCSS

Breathlessness, Cough, and Sputum Scale

- ITT

Intention-to-Treat

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health O. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M. Deaths : leading causes for 2019. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2021;70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Disease GIfCOL. Guide to COPD diagnosis, management, and prevention: A guide for healthcare professional. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klepeis NE, Nelson WC, Ott WR, Robinson JP, Tsang AM, Switzer P, et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology. 2001;11(3):231–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leech JA, Smith-Doiron M. Exposure time and place: do COPD patients differ from the general population? Journal of exposure science & environmental epidemiology. 2006;16(3):238–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansel NN, Putcha N, Woo H, Peng R, Diette GB, Fawzy A, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Air Cleaners to Improve Indoor Air Quality and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Health: Results of the CLEAN AIR Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2022;205(4):421–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangakis CE, Rubin DB. Principal stratification in causal inference. Biometrics. 2002;58(1):21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM, Littlejohns P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145(6):1321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. European Respiratory Journal. 2009;34(3):648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones PW, Wedzicha JA. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leidy NK, Rennard SI, Schmier J, Jones MK, Goldman M. The breathlessness, cough, and sputum scale: the development of empirically based guidelines for interpretation. Chest. 2003;124(6):2182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansel NN, McCormack MC, Belli AJ, Matsui EC, Peng RD, Aloe C, et al. In-Home Air Pollution Is Linked to Respiratory Morbidity in Former Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187(10):1085–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng RD, Butz AM, Hackstadt AJ, Williams DAL, Diette GB, Breysse PN, et al. Estimating the health benefit of reducing indoor air pollution in a randomized environmental intervention. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society). 2015;178(2):425–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y, Song X, Wu R, Fang J, Liu L, Wang T, et al. A review on reducing indoor particulate matter concentrations from personal-level air filtration intervention under real-world exposure situations. Indoor air. 2021;31(6):1707–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butz AM, Matsui EC, Breysse P, Curtin-Brosnan J, Eggleston P, Diette G, et al. A randomized trial of air cleaners and a health coach to improve indoor air quality for inner-city children with asthma and secondhand smoke exposure. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2011;165(8):741–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthén BO. Beyond SEM: General Latent Variable Modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29(1):81–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo B, Muthén BO. Modeling of intervention effects with noncompliance: A latent variable approach for randomized trials. New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling: Psychology Press;2001. p. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood RA, Johnson EF, Van Natta ML, Chen PH, Eggleston PA. A placebo-controlled trial of a HEPA air cleaner in the treatment of cat allergy. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1998;158(1):115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanphear BP, Hornung RW, Khoury J, Yolton K, Lierl M, Kalkbrenner A. Effects of HEPA Air Cleaners on Unscheduled Asthma Visits and Asthma Symptoms for Children Exposed to Secondhand Tobacco Smoke. 2011;127(1):93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Causal Effects in Clinical and Epidemiological Studies Via Potential Outcomes: Concepts and Analytical Approaches. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21(1):121–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Fergusson D, Maltais F, Bourbeau J, Goldstein R, et al. Tiotropium in Combination with Placebo, Salmeterol, or Fluticasone–Salmeterol for Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;146(8):545–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creutzberg EC, Wouters EFM, Mostert R, Pluymers RJ, Schols AMWJ. A Role for Anabolic Steroids in the Rehabilitation of Patients With COPD?*: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized Trial. Chest. 2003;124(5):1733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubel AM, Stewart ML, Stencel JM. Activated carbon for control of nitrogen oxide emissions. Journal of Materials Research. 1995;10(3):562–7. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.