Abstract

In past several years, mannanases has attracted many researchers owing to its extensive industrial applications. The search for novel mannanases with high stability still continues. Present investigation was focused on purification of extracellular β-mannanase from Penicillium aculeatum APS1 and its characterization. APS1 mannanase was purified to homogeneity by chromatography techniques. Protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS/MS revealed that the enzyme belongs to GH family 5 and subfamily 7, and possesses CBM1. The molecular weight was found to be 40.6 kDa. The optimum temperature and pH of APS1 mannanase were 70 °C and 5.5, respectively. APS1 mannanase was found to be highly stable at 50 °C and tolerant at 55–60 °C. The enzyme was very sensitive to Mn+2, Hg+2 and Co+2 metal ions and stimulated by Zn+2. Inhibition of activity by N-bromosuccinimide suggested key role of tryptophan residues for catalytic activity. The purified enzyme was efficient in hydrolysis of locust bean gum, guar gum and konjac gum and kinetic studies revealed highest affinity towards locust bean gum (LBG). APS1 mannanase was found to be protease resistant. Looking at the properties, APS1 mannanase can be a valuable candidate for applications in bioconversion of mannan-rich substrates into value-added products and also in food and feed processing.

Keywords: β-Mannanase, Penicillium, GH5 family, CBM1, Thermotolerant, Protease resistant

Introduction

Currently, hemicellulases have emerged as vital enzymes for wide range of biotechnological applications, due to their multidimensional functions. Mannanases such as β-mannanase and β-mannosidase are key enzymes for depolymerization of mannan-rich hemicellulosic component present in softwood, in leguminous endosperm and in beans. Mannans and hetero-mannans, such as galactomannan, glucomannan and galacto-glucomannan, are composed of linear or branched polymers derived from hexose sugars, viz. d-mannose, d-glucose and d-galactose (Felicia and Onilude 2013). The key enzyme that participate in the degradation of mannan and hetero-mannan is endo-1,4-β-mannanase (E.C. 3.2.1.78) which initiates depolymerization of mannan by random hydrolysis of 1,4-β-mannosidic linkages within the backbone. Generally, the digestion of mannan polysaccharides by 1,4-β-mannanase produces mannooligosaccharides, viz. mannobiose, mannotriose and mannotetraose (Chauhan et al. 2012).β-Mannanases are members of glycoside hydrolase (GH) class of enzymes. They are classified into GH families 5, 26, 113 and 134 based on their sequence similarities in Carbohydrate Active Enzymes database (CAZy; http://www.cazy.org/; Drula et al. 2022). The majority of fungal mannanases belong to GH5 family including mannanases from Aspergillus aculeatus, Trichoderma reesei and Agaricus bisporus (Dhawan and Kaur 2007). All mannanases exhibit conserved amino acids, two glutamates (as acid/base and nucleophile), located at the active site. The mode of action of enzymes belonging to GH5 family is a classical retaining mechanism which facilitates both hydrolytic and transglycosylating activities (Rosengren et al. 2014). Largely mannanases exhibit a modular organization and generally consist of two-domain proteins. These proteins contain structurally distinct catalytic and non-catalytic domains. The most important non-catalytic module is carbohydrate-binding module (CBM) which facilitates binding of enzyme to insoluble polysaccharide enhancing the glycoside hydrolytic efficiency. Certain β-mannanases of GH5 family includes a family 1 carbohydrate-binding module (CBM1) at N- or C-terminal (Hägglund et al. 2003).

Mannan and its hydrolysis products, mannooligosaccharides, are highly valuable in food, feed and pharmaceutical industries and thereby attracting many researchers. Mannanases also find applications in paper and pulp industries, in reduction of viscosity of coffee extracts, oil drilling, and as hydrolytic agents in detergents, slime control agents, fish feed additives, etc. (Srivastava and Kapoor 2017). Looking at the wide spectrum of industrial applications of mannanases, search for novel and robust microbial enzymes is still needed for development of efficient green processes. Purified β-mannanases are important for few commercial applications and it is necessary for determination of primary amino acid sequence, to determine their three dimensional structure for designing and to engineer for specific functions. The characterization of purified enzyme can be helpful to decide its applicability for suitable industrial process. In last few decades, research was also focused on highly active β-mannanase by mutating enzyme producing strains, recombination and optimization of production process. For industrial applications of β-mannanases, apart from high enzymatic activities, properties such as thermal stability, pH stability, resistance to proteases, and adsorption capability need to be investigated.

In last few years, after Aspergillus and Trichoderma, it is realized that Penicillium sp. are also a promising source of enzyme cocktails rich in cellulases and hemicellulases. Penicillium aculeatum APS1 was isolated in our laboratory and production of β-mannanases was optimized using statistical tools. Substantially, high yield of β-mannanases was obtained using solid-state fermentation on mixture of palm kernel cake and soybean meal. Moreover, its ability to produce mannooligosaccharides was also investigated (Bangoria et al. 2021). In view of above information, the present study was focused on purification and biochemical characterization of β-mannanases from newly isolated Penicillium aculeatum APS1.

Materials and methods

Materials

Locust bean gum (LBG), mannose, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-mannopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-α-d-galactopyranoside, p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, bovine serum albumin (BSA), DEAE Sepharose fast flow, Sephacryl S-200, N-ethylmaleimide, N-bromosuccinimide, 1-acetylimidazole were procured from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Konjac glucomannan (KG) was purchased from Now Foods, United States. Guar gum (GG) was acquired from Himedia, India. Xylan from beechwood was purchased from SRL, India. Protein ladder for SDS-PAGE was obtained from Puregene. All the other chemicals used were of analytical grade. Palm kernel cake (PKC) and soybean meal (SM) used for β-mannanase production was procured from local market.

Enzyme production and extraction

β-Mannanase was produced under solid-state fermentation using palm kernel cake (PKC) and soybean meal (SM) with optimized conditions as mentioned by Bangoria et al. (2021). Briefly, PKC and SM in ratio 4:1 were mixed with mineral salt medium at 52.25% moisture level and inoculated with spore suspension of P. aculeatum APS1. The flask was incubated at 30 ℃ for 130 h with intermittent mixing.

After incubation, APS1 mannanase was extracted using 30 mL sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.3) under shaking condition for 30 min. The content of the flask was filtered through muslin cloth and centrifuged at 7745×g for 15 min at 20 ℃. The clear supernatant was used as crude β-mannanase.

Enzyme assays

β-Mannanase activity was measured by mixing 0.2 mL appropriately diluted enzyme and 1.8 mL of 0.5% locust bean gum (LBG) as substrate. The reaction system was incubated at 50 ℃ for 10 min followed by termination of reaction by adding 1 mL of DNS reagent. The released reducing sugar was analyzed at 540 nm (Miller 1959) as mannose equivalent. One unit of β-mannanase activity was defined as amount of enzyme liberating 1 µmol mannose per minute under assay conditions. The other cellulolytic and hemi-cellulolytic enzymes were assayed according to Bangoria et al. (2021).

Protein estimation

The protein concentration was estimated by Folin’s method as described by Lowry et al. (1951) using BSA as standard.

Purification of β-mannanase from P. aculeatum APS1

Purification

Purification of β-mannanase was achieved by ammonium sulfate fractionation, anion exchange chromatography (AEC) and gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The crude β-mannanase was subjected to saturation with 40-60% ammonium sulfate for 12 h at 4 ℃. The precipitates formed were collected by centrifugation at 7745×g for 20 min and dissolved in minimum volume of sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.3) followed by dialysis for 24 h against the same buffer at 4 ℃. This enzyme was loaded onto DEAE Sepharose equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8). A linear gradient of 0.0-0.5 M NaCl prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8) was used to elute proteins at flow rate of 1 mL/min. Fractions with high specific activity of β-mannanase were pooled, concentrated and desalted using 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 5.3) by ultrafiltration using Amicon Ultra 3.0 kDa cutoff membrane (Millipore) at 4 ℃. The concentrated enzyme was passed through Sephacryl S-200 equilibrated with sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.3) at flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Fractions of 0.5 mL were collected and analyzed for protein concentration and β-mannanase activity. Purity of APS1 mannanase was examined by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

SDS-PAGE and zymography

SDS-PAGE with 5% stacking and 12% resolving gel was performed according to Laemmli (1970). Protein marker was run parallel to samples. Protein bands were detected by silver staining method. For activity staining, duplicate gel was run and washed with 20% isopropanol to remove excess SDS followed by buffer washes. Zymography for β-mannanase activity was performed as mentioned by Bangoria et al., (2021). The gel was scanned by gel documentation system (Bio-Rad) and molecular weight of purified protein was evaluated by automated image analysis software using standard protein markers as reference.

Characterization of APS1 mannanase

Protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS/MS

The pure protein bands of APS1 mannanase were excised from SDS-PAGE gel and sent for partial protein sequencing by MALDI-TOF MS/MS at Central Instrumentation Facility, IIT Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India. The protein gel bands were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion using standardized protocol. Subsequently, the peptides generated were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS/MS (Bruker). The protein MS spectra were compared with the sequence of endo β-mannanase from Penicillium rubens using Biotools software and MASCOT server (https://www.matrixscience.com/). Further, each of the masses was selected and subjected to LIFT, and then again subjected to MS/MS analysis using Biotools. The highly similar sequences were downloaded from NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and multiple sequence alignment was carried out using Clustal omega of Uniprot database (https://www.uniprot.org/; Bateman et al. 2023). The matched peptide was subjected to CD search tool of NCBI to identify the conserved domains. The sequencing data for fungal GH5 family endo β-mannanases with identified subfamily were retrieved from CAZy database for phylogenetic analysis (CAZy; http://www.cazy.org/; Drula et al. 2022). The Clustal W method was used to align retrieved sequences (Thompson et al. 2003). Phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor-joining method using MEGA X (Kumar et al. 2018). Tree was visualized using Tree Graph 2 (Stöver and Müller 2010).

Effect of temperature on APS1 mannanase activity and stability

APS1 mannanase activity was performed at different temperatures ranging from 35 to 80 ℃ to determine optimum temperature of purified β-mannanase at pH 5.3. The effect of temperature on stability of enzyme was studied at 40, 50, 55, 60 and 65 ℃ and at pH 5.3. Residual activity was evaluated intermittently using standard assay conditions. Half-life (t1/2) of APS1 mannanase was evaluated at different temperatures according to first-order kinetics. The decimal reduction time (D value), Z value, activation energy for APS1 mannanase deactivation (Ea(d)) and thermodynamics functions such as change in enthalpy (∆H*), Gibbs free energy (∆G*) and entropy (∆S*) were also evaluated (Siham A. Ismail et al. 2019a, b).

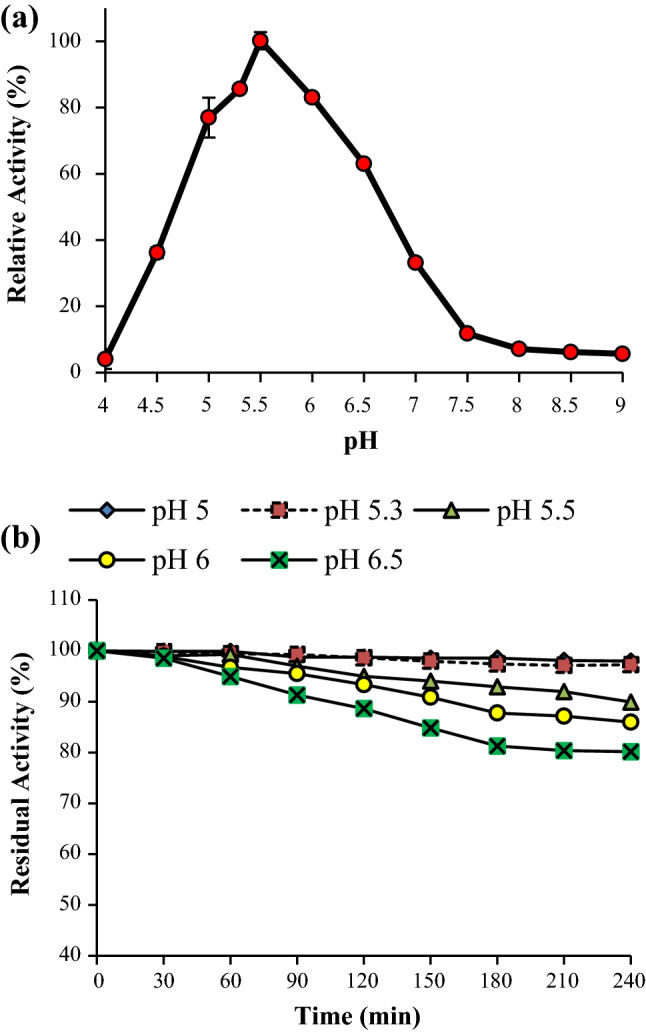

Effect of pH on APS1 mannanase activity and stability

The optimum pH for purified APS1 mannanase was determined by assaying relative activity at different pH ranging from 3.0 to 9.0 using sodium citrate buffer for pH 3.0–6.0, sodium phosphate buffer for pH 6.5 to 8 and glycine-NaOH buffer for pH 8.5 and 9.0 at 50 ℃. To study the stability of APS1 mannanase at different pH, the enzyme was appropriately diluted in different pH buffer and incubated at ambient temperature. The residual activity was measured at specific time intervals.

Determination of kinetic parameters

The kinetic parameters of APS1 mannanase such as Michaelis constant (Km) and maximum velocity (Vmax) for LBG, KG and GG as substrate were evaluated using Lineweaver–Burk plot. The β-mannanase activity was analyzed for varying concentrations of substrates ranging from 0.5 to 4.5 mg/mL in sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.3) at 50 ℃.

Effect of metal ions, surfactants, additives and inhibitors on APS1 mannanase activity

APS1 mannanase activity was assayed in the presence of various metal ion salts to determine their influence on enzyme activity. Metal ion salts, viz. CaCl2, HgSO4, MnSO4, ZnSO4, FeSO4, BaCl2, CoCl2, KCl, CuSO4, MgSO4, AlCl3 and NiCl2 were added in reaction mixture at 1, 5 and 10 mM concentration. The effect of different surfactants such as SDS, Tween 20, Tween 80 and Triton-X-100 at concentration of 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 % on APS1 mannanase activity was also assessed. The impact of additives on enzyme activity was studied by incorporating dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium azide (NaN3), β-mercaptoethanol (BME), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at concentration of 1, 5 and 10 mM in reaction system. Inhibitors such as N-ethylmaleimide, N-bromosuccinimide and 1-acetylimidazole were incubated with APS1 mannanase at different concentrations of 1-5 mM for 30 min. The residual activity was assayed under standard assay condition and compared with control.

Stability of APS1 mannanase in the presence of NaCl and urea

APS1 mannanase was incubated with NaCl and urea with concentration of 1-3 M for 30 min and assayed under standard assay condition. The residual activity was measured by comparing with control.

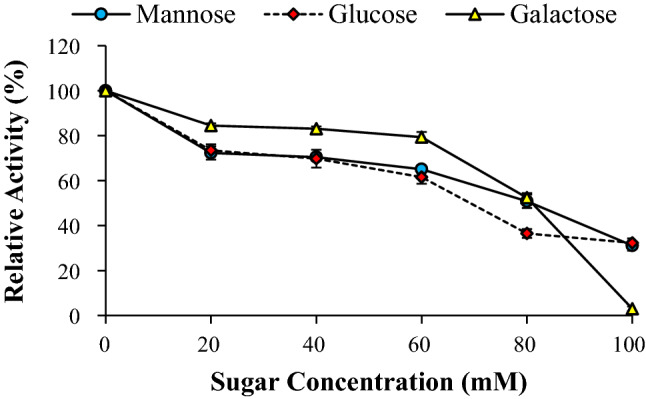

Effect of sugars on APS1 mannanase activity

The influence of sugars, viz. d-mannose, d-glucose and d-galactose on activity of APS1 mannanase was determined by adding 0-100 mM of sugars in the reaction mixture. The relative activity of enzyme was determined by comparing with controls.

Substrate specificity

The substrate specificity of APS1 mannanase was evaluated using different substrates such as LBG (0.5%), GG (0.5%), KG (0.5%), filter paper (50 mg), CMC (1%), Avicel (1%), xylan (1%) and PNP-glycosides (1 mM). The relative activity was calculated by measuring released sugar by DNS method (Miller 1959).

Adsorption assay

Microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel PH101, Sigma-Aldrich) was equilibrated with sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.3). The fixed protein concentration of APS1 mannanase, 2.33 µg (2.78 U/mL), was mixed with 0-20 mg/mL Avicel and incubated for 1 h at 4 ℃ under mild agitation. The enzyme bound Avicel was separated by centrifugation at 7745×g at 4 ℃ for 10 min. The supernatant was analyzed for β-mannanase activity under standard assay conditions. The adsorption (%) of protein was calculated by comparing enzyme activity in supernatant of control set (not containing Avicel).

Resistance to proteases

Protease resistance was examined by incubation APS1 mannanase at 37 °C for 60 min with trypsin (pH 7, >2500 USP/mg, Himedia) and pepsin (pH 2.5, 3000-3500 NF U/mg, Himedia) at ratio of 1:10 (mannanase:protease, w/w). The residual activity was measured under standard assay condition. The control was kept by incubating APS1 mannanase without proteases.

All the experiments were performed in triplicates and error bar indicates the standard deviation of the mean value.

Results and discussion

Purification of β-mannanase from P. aculeatum APS1

Purification summary of APS1 mannanase has been mentioned in Table 1. The specific activity of APS1 mannanase was found to increase by 11.34 fold. It is evident from Fig. 1 that crude β-mannanase is purified to a single protein band with molecular weight of 40.6 kDa. The molecular weight of GH5 family β-mannanases from Penicillium oxalicum GZ-2, Talaromyces leycettanus JCM12802, Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Trichoderma reesie and Aspergillus nidulans AZ3 were reported to be 61.6 kDa, 72 kDa, 65 kDa, 53.6 kDa and 42.2 kDa, respectively (Benech et al. 2007; Hägglund et al. 2003; Lu et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015; Liao et al. 2014).

Table 1.

Summary of purification of APS1 mannanase

| Sample | Total Units | Total Protein (mg) | Specific Activity (U/mg) | Fold Purification | %Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | 39,600 | 1032 | 38 | 1 | 100 |

| Dialysed ammonium sulfate fraction (40–60%) | 21,461 | 154 | 139 | 3.60 | 54 |

| Anion exchange chromatography (AEC) | 6952 | 21.29 | 326 | 8.57 | 17.50 |

| Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) | 625 | 1.45 | 431 | 11.34 | 1.57 |

Ammonium sulfate fraction and dialysis was carried out at 4 ℃, chromatographic techniques were performed at 25 ℃

Fig. 1.

SDS-PAGE and zymogram; Lane 1: protein marker; Lane 2: Crude β-mannanase; Lane 3: Ammonium sulfate fraction (40–60%); Lane 4: Ion exchange fraction; Lane 5: GPC fraction (purified APS1 mannanase); Lane 6: Zymogram of APS1 mannanase

Characterization of APS1 mannanase

Partial amino acid sequencing of APS1 mannanase

MALDI-TOF MS/MS analysis was carried out and the protein sequence was compared with protein database available publically. A total of 88 peptides were generated after trypsin digestion (data not shown). The sequence match was done with Biotools software (patented by Bruker) and MASCOT server (https://www.matrixscience.com/). When successful hits were not obtained, the sequence of the protein of interest, endo β-mannanase from Penicillium rubens, was obtained from NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and subjected to virtual digest. The digested peptides obtained were matched with query peptides (trypsin digested APS1 mannanase) and 52.9% similarity was found. The matched peptide with P. rubens β-mannanase is shown in red (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Peptides (shown in red) of APS1 mannanase matching with sequence of endo-β-1,4-mannanase F of Penicillium rubens (Accession number: B6HVQ6). b Graphical summary of GH family showing the presence of CBM-1

The analysis of amino acid sequence suggested that this enzyme belongs to GH5 family with CBM1, cellulose-binding module belonging to family 1, at C-terminus (Fig. 2b). CBM1 is mainly found in GH5, GH6, GH7 and GH46 (Sidar et al. 2020). The CBM1 in β-mannanase has been reported to promote the association between enzyme and substrate and contribute to enzyme thermostability (Wang et al. 2015). Fusion of CBM1 with catalytic domain of Aspergillus usamii β-mannanase improved thermostability and cellulose-binding capacity (Tang et al. 2013). GH5 family β-mannanase from Talaromyces leycettanus JCM12802 also possess CBM1 and decrease in thermostability was observed in mutant β-mannanase devoid of CBM1 (Wang et al. 2015). GH5 β-mannanases from Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Trichoderma reesie, Aspergillus nidulans AZ3 also contains CBM belonging to family 1 at N- or C-termini (Benech et al. 2007; Hägglund et al. 2003; Lu et al. 2014).

Multiple sequence alignment of GH5 family β-mannanases with APS1 mannanase is shown in Fig. 3. Phylogenetic analysis of known β-mannanase revealed that APS1 mannanase was clustered into GH family 5 subfamily 7 which possess CBM1 (Fig. 4) and clearly distinct from the GH family 26 containing CBM35. According to CAZy database (CAZy; http://www.cazy.org/; Drula et al. 2022), most of the fungal β-mannanase reported belongs to GH5 family. Very few reports are available for GH26 fungal β-mannanase. Apart from that, only one report is available for GH134 β-mannanase from Rhizopus microspores var. rhizopodiformis. The enzymes within GH5_7 are exclusively mannanases including β-mannosidases, endo β-1,4-mannanases and β-1,4-mannan transglycosylases (CAZy; http://www.cazy.org/; Drula et al. 2022). β-Mannanase from GH5_7 has also been reported from Talaromyces cellulolyticus (Uechi et al. 2020). GH5_7 subfamily has been classified in the largest glycoside hydrolase clan GH-A. GH5_7 subfamily enzymes have (β/α)8 TIM barrel 3D structure and follows retaining mechanism.

Fig. 3.

Multiple sequence alignment of GH5 endo-beta-1,4-mannanase. The endo-beta-1,4-mannanase sequences used for multiple sequence alignment were from Penicillium rubens (B6HVQ6), Penicillium oxalicum (AGW24296), Aspergillus nidulans (AGG69666), Trichoderma viride (AFP95336) and Penicillium aculeatum APS1 (present study). The consensus sequences are shown with asterisk marks

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of known GH5 family β-mannanases. β-Mannanase from P. aculeatum APS1 is shown in bold

Effect of temperature on activity and stability of APS1 mannanase

The impact of temperature on APS1 mannanase activity was evaluated in the range of 35–80 ℃. The optimum temperature for APS1 mannanase activity was found to be 70 ℃ (Fig. 5a). β-Mannanases of P. italicum and A. terreus FBCC 1369 were also shown to be optimally active at 70 ℃ (Olaniyi 2014; Soni et al. 2016). However β-mannanases from P. oxalicum GZ-2 and Penicillium humicola were optimally active at 80 ℃ and 60 ℃, respectively (Ismail et al. 2019a, b; Liao et al. 2014). This difference of optimum temperatures can be due to thermal irreversible inactivation of enzyme above optimal temperature and difference in their energy of activation for denaturation of enzymes (Thomas and Scopes 1998).

Fig. 5.

a Effect of temperature on APS1 mannanase activity, b effect of temperature on APS1 mannanase stability, c thermal inactivation kinetics for APS1 mannanase at different temperature, and d Arrhenius plot for activation energy. APS1 mannanase activity was performed at pH 5.3 for 10 min at 50 ℃

Thermostability of APS1 mannanase was checked in the range of 40-65 ℃. The enzyme was found to be highly stable at 40 ℃, 45 ℃ and 50 ℃ temperature. At temperatures 55 °C and 60 °C, the enzyme showed stability above 50% for about 4 h. However, the residual activity was drastically reduced within 30 min at 65 ℃ and 70 ℃ (Fig. 5b). Generally, thermal stability of enzymes is related to some structural features such as decreased loop length, increase in secondary structure, less heat liable residues (cysteine, asparagine and glutamine), etc. (Poulos 2003). Figure 5c shows the plot of ln(Et/E0) versus time for temperatures 50, 55 and 60 ℃, which clearly reveals inactivation by the first-order kinetics.

Half-life (t1/2) of an enzyme indicates the time require by an enzyme to lose its initial activity by half at specific temperature. Half-lives of APS1 mannanase were 19.90 h, 6.71 h and 2.54 h at 50, 55 and 60 ℃, respectively. However half-lives of β-mannanase from Trichoderma longibrachiatum RS1 were 10.5 h, 0.84 h and 0.33 h at 55, 60 and 65 ℃, respectively, whereas half-life of β-mannanase from P. humicola and Pyrenophora phaeocomes S-1 was 6.41 h and 2 h, respectively, at 50 ℃ (Ismail et al. 2019a, b; Soni et al. 2015). In contrast, higher half-life of 55 h at 60 ℃ for cloned β-mannanase from P. oxalicum GZ-2 has been reported (Liao et al. 2014).

The D-value, decimal reduction time, is a factor indicating the stability of an enzyme and is defined as the time required for an enzyme to reduce its initial activity by 90%. The D value for APS1 mannanase at temperatures 50, 55 and 60 °C were 66.14 h, 22.3 h and 8.43 h, respectively. This result showed that APS1 mannanase was highly stable for prolong period of time at 50 °C. The Z value is increase in temperature required to decrease 90% of D value. Generally, higher Z value indicates greater thermostability of enzyme. The Z value for APS1 mannanase was 11.7 ℃.

To calculate the activation energy for APS1 mannanase deactivation, Arrhenius plot [ln (k) versus 1/T] was drawn (Fig. 5d). The linearity of this plot suggested that inactivation of APS1 mannanase occurs due to a temperature-dependent mechanism, such as protein unfolding. The activation energy for APS1 mannanase deactivation was 184.4 kJ/mol (50-60 ℃), which was found to be higher than for β-mannanase from .P humicola (Ismail et al. 2019a, b).

The thermodynamics of thermal inactivation of APS1 mannanase was studied by calculating Gibbs free energy change (∆G*), enthalpy change (∆H*) and entropy change (∆S*). These were calculated from experimental data in temperature range 50–60 ℃ (Table 2). The values of thermodynamic functions are good tools to understand thermal stability of enzyme for heat-induced denaturation process. This information could help to determine if any stabilization or destabilization effects that could have been overlooked when only the half-life times are considered (Deylami and Rahman 2014). The change in Gibbs free energy is considered as barrier for enzyme inactivation, the enthalpy change indicates the number of bonds broken during thermal inactivation and the entropy change indicates net enzyme and solvent disorder (Djina et al. 2021). In this study, with increase in temperature, ∆H* value remained same which indicates that enthalpy is temperature independent and thus, there is no change in enzyme heat capacity. The positive value of ∆H* suggest the nature of thermal inactivation is endothermic. Moreover, enthalpy is the measure of number of non-covalent bonds broken during heat treatment to form transition state for enzyme inactivation. Therefore, higher enthalpy demonstrates more number of non-covalent bonds present in enzyme, leading to more stability (Gouzi et al. 2012). The positive value of ∆G* indicates that the thermal inactivation of these reactions do not occur spontaneously. ∆G* values were slightly decreasing with increase in temperature showed the destabilization of protein with rise in temperature. The similar and positive values of ∆S* in temperature range 50–60 ℃ indicate that the reaction system was disordered at the end of the reaction and the enzyme has undergone distortion (Gouzi et al. 2012). The thermal inactivation of APS1 mannanase could be described by first-order kinetic model. The values of half-live; D-, kd- and Z values; high value of activation energy for denaturation and change in enthalpy indicated that high amount of energy is required to initiate denaturation of APS1 mannanase, might be due to its stable molecular conformation. This high thermostability of APS1 mannanase can be considered to be used in any industrial processes occurring at higher temperatures.

Table 2.

Thermodynamics study of irreversible inactivation of APS1 mannanase

| Temperature | ∆H* (kJ mol−1) | ∆G* (kJ mol−1) | ∆S* (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 ℃ | 181.7 | 99.37 | 0.336 |

| 55 ℃ | 181.6 | 97.99 | 0.337 |

| 60 ℃ | 181.6 | 96.83 | 0.336 |

Effect of pH on activity and stability of APS1 mannanase

The optimum pH for APS1 mannanase activity was found to be pH 5.5 (Fig. 6a). The relative activity at pH 5-6.5 was remarkable. The enzyme was also active at pH 4.5 and 7 with more than 30% activity. However, the enzyme was very sensitive to pH below 4.5 and at alkaline pH. The optimum pH of β-mannanase from P. occitanis Pol6 and P. oxalicum GZ-2 was pH 4 whereas pH 5 for β-mannanase from P. italicum (Blibech et al. 2010; Liao et al. 2014; Olaniyi 2014). APS1 mannanase was highly stable at pH 5 and 5.3 retaining 97% activity after 4h (Fig. 6b). The residual activities at pH 5.5, 6 and 6.5 were 89.9%, 85.9% and 80.15%, respectively, after 4 h at room temperature. This result reveals the stability of APS1 mannanase in moderately acidic condition. β-Mannanase from P. oxalicum GZ-2 was reported to be highly stable in pH range of 3-7 at 60 ℃ for 2 h (Liao et al. 2014).

Fig. 6.

a Effect of pH on APS1 mannanase activity, b effect of pH on APS1 mannanase stability. APS1 mannanase activity was performed at pH 5.3 for 10 min at 50 ℃

Determination of kinetic parameters

The effect of substrate concentration on APS1 mannanase activity was analyzed at 50 ℃ and pH 5.3. The kinetic parameters such as Michaelis constant (Km) and maximum velocity (Vmax) were evaluated using Lineweaver–Burk Plot (Fig. 7). The Km and Vmax of APS1 mannanase for locust bean gum (LBG), guar gum (GG) and konjac gum (KG) are as listed in Table 3. The Km of APS1 mannanase for the various natural mannans were in the order of LBG < GG < KG. The turnover number (Kcat) and catalytic efficiency (Kcat/Km) of APS1 mannanase for these three substrates are also mentioned in Table 2. Comparatively, affinity of APS1 mannanase to LBG was much higher than β-mannanase from P. oxalicum GZ-2 (Liao et al. 2014) and A. terreus FBCC 1369 (Soni et al. 2016).

Fig. 7.

Lineweaver–Burk Plot for determination of kinetic parameters. APS1 mannanase activity was measured using LBG, KG and GG at various concentrations at 50 ℃, pH 5.3 for 10 min

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of β-mannanase from Penicillium aculeatum APS1 for various natural mannans

| Substrate |

Vmax (µmol/mL/mg) |

Km (mg/mL) |

Kcat (s−1) |

Kcat/Km (mL/s/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBG | 483 | 0.90 | 33.1 | 33.7 |

| GG | 410 | 2.31 | 27.8 | 12.0 |

| KG | 406 | 2.96 | 28.1 | 9.5 |

Enzyme assay was carried out using various substrates with increasing concentration under standard assay conditions

LBG Locust bean gum, GG Guar gum, KG Konjac glucomannan

Effect of metal ions, surfactants and other additives on APS1 mannanase activity

The effect of various metal ions and additives in range of 1-10 mM concentration was tested on APS1 mannanase activity (Fig. 8a). Mn2+, Hg2+ and Co2+ strongly inhibited the enzyme activity, whereas Zn2+ activated APS1 mannanase activity. Similar results were observed by (Blibech et al. 2010; Liao et al. 2014; Olaniyi 2014; Wang et al. 2016). In case of additives, it was observed that with increasing the concentration of additives APS1 mannanase activity tend to decrease. Furthermore, APS1 mannanase activity was strongly reduced in the presence of β-mercaptoethanol, PMSF and EDTA at 10 mM concentration (Fig. 8b). β-Mercaptoethanol is a strong reducing agent which may affect the folding of enzyme containing disulfide linkages resulting in denaturation of protein of interest. The reduction in APS1 mannanase activity in the presence of PMSF shows the presence of serine residues at catalytic site. Furthermore, as EDTA is a metal ion chelator and reduced APS1 mannanase activity, showed that β-mannanase might be a metallo-enzyme. The influence of different surfactants on APS1 mannanase activity was also determined. The results obtained showed that at low concentration of SDS, APS1 mannanase activity was increased by 21%. However, at high concentration of all the surfactants tested, enzyme activity was reduced to about 75% (Fig. 8c). Chemical inhibitors known to modify specific group of amino acid were used to determine the presence of few amino acids at catalytic and/or binding site. APS1 mannanase was incubated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 1-acetylimidazole (1-Al) and N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) at different concentration. These inhibitors cause modification in cysteine, tyrosine and tryptophan amino acid residues, respectively. With increase in concentration of chemical inhibitors, there was decrement in APS1 mannanase activity. The residual activity of APS1 mannanase was 57.6% and 45.4% at 5 mM concentration of N-ethylmaleimide and 1-acetylimidazole, respectively. This reduction in activity of enzyme projects the role of cysteine and tyrosine in catalysis of substrate. The residual activity of β-mannanase was absolutely declined in the presence of N-bromosuccinimide (Fig. 8d). This result strongly suggests the presence of tryptophan on binding or catalytic site of β-mannanase. Similarly, β-mannanases from B. licheniformis HDYM-04 and L. casei HDS-01 showed drastic reduction in activity in the presence of these chemical inhibitors (Ge et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2020).

Fig. 8.

Effect of a metal ions, b additives, c surfactants, and d inhibitors on APS1 mannanase activity. APS1 mannanase activity was assayed in the presence of various metal ions, additives, surfactants and inhibitors at standard assay conditions. (BME: β-mercaptoethanol)

Stability APS1 mannanase in the presence of NaCl and urea

NaCl and urea are known to denature protein. Some marine algae are rich in mannan and are great source of complex sugars. Considering the average salinity of sea (3.5%), the application of mannanase in sea food processing and marine products require salt tolerance of enzymes (You et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2012). APS1 mannanase was found to be moderately tolerant to NaCl. The residual activity of APS1 mannanase was decreasing with increasing concentration of NaCl in the range of 1-3 M. The residual activities of β-mannanase were 53.72%, 40.69% and 31.51% at 1 M, 2 M and 3 M NaCl, respectively, after 30 min of incubation. Moreover, APS1 mannanase was not found to be tolerant to urea. The residual activities in the presence of urea were only 25.26%, 13.29% and 2.34% at 1 M, 2 M and 3 M concentrations, respectively. Tolerance of enzyme to urea can be helpful for biodegradation of raw agricultural waste where urea is used as organic fertilizer. In contrast, β-mannanase from Bacillus sp. CSB39 retained >55% activity at 0.5-15% NaCl (2.56 M) and >80% activity in 3 M urea (Regmi et al. 2016). β-Mannanase from B. licheniformis HDYM-04 retained almost 100% activity at 1 M NaCl, however 80% enzyme activity was reduced in the presence of 1 M urea (Ge et al. 2016).

Effect of sugars on APS1 mannanase activity

The major monosaccharides present in hydrolysates of galacto/gluco-mannan-rich biomass include mannose, galactose and glucose. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the tolerance of the enzyme against these sugars for application in enzymatic hydrolysis of mannan polysaccharides. The effect of these sugars on β-mannanase was evaluated in range of 0–100 mM sugars. As shown in Fig. 9, relative activity of APS1 mannanase was decreasing with increase in sugar concentration. The APS1 mannanase activity in the presence of 60 mM sugars was retained above 60%. Moreover, activity was reduced to 30% at 100 mM mannose and glucose. However, in the presence of galactose, the enzyme activity was totally declined at 100 mM concentration. β-Mannanase from Clostridium saccharoperbutylacetonicum N1-4 was used for saccharification of PKC and it was showed that major monosaccharide released was mannose up to 16 g/L (88 mM) and no substrate inhibition effect on enzyme was observed (Hamid et al. 2016).

Fig. 9.

Effect of sugars on activity of APS1β-mannanase. APS1 mannanase activity was measured in the presence of monomeric sugars at different concentrations under standard assay conditions

Substrate specificity

The action of APS1 mannanase on different substrates was measured to determine the substrate specificity of the enzyme. As shown in Table 4, relative activity (%) of APS1 mannanase towards different mannan polysaccharides, viz. LBG (galactomannan), KG (glucomannan) and GG (galactomannan) was 100%, 85.18% and 51.40%, respectively. Despite the fact that LBG and GG are chemically galactomannan, APS1 mannanase activity towards LBG was twice the activity towards GG. Moreover, β-mannanase showed no detectable activity on other carbohydrates such as carboxymethyl cellulose, filter paper, xylan and Avicel under the assay conditions. Based on this result, it was supposed that the enzyme was strictly active on mannan polysaccharides with no additional glycoside hydrolase activities. Besides, it has been reported that β-mannanase with more than two distinct catalytic domains were able to perform catalysis on multiple substrates which are structurally not related (Palackal et al. 2007). Moreover, APS1 mannanase was unable to hydrolyze all the tested PNP-sugar derivatives. β-Mannanase from Cellulosimicrobium sp. strain HY-13 also showed similar specificity towards only mannan polymers and no activity on other carbohydrate polymers and PNP-substrates was observed (Young et al. 2011). Similarly, Jana et al. (2018) also showed that β-mannanase from A. oryzae had higher affinity towards LBG and KG than towards GG. In addition, the enzyme was inactive on gum Arabic, fenugreek gum and CMC.

Table 4.

Substrate specificity of APS1 mannanase for various carbohydrates and PNP-derivatives

| Substrates | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|

| LBG | 100 ± 3.6 |

| KG | 85.18 ± 4.1 |

| GG | 51.4 ± 1.7 |

| CMC | ND |

| Filter paper | ND |

| Xylan | ND |

| Avicel | ND |

| PNP-mannopyranoside | ND |

| PNP-galactopyranoside | ND |

| PNP-glucopyranoside | ND |

LBG Locust bean gum, KG Konjac gum, GG Guar gum, CMC carboxymethyl cellulose, ND Not detected

Adsorption assay

When equal amount of APS1 mannanase was added to different concentration of Avicel, the adsorption capacity increased gradually with increase in Avicel concentration (Fig. 10). At 10 mg/mL Avicel, 80% adsorption was observed and 100% enzyme was adsorbed when mixed with 20 mg/mL Avicel. This result suggests that the presence of CBM1 in modular structure of APS1 mannanase improves the association of enzyme onto insoluble cellulose, making the enzyme more suitable for hydrolysis of raw biomass such as softwood for generation of fermentable sugars. Similar observations were reported by Ma et al. (2017) where β-mannanase from T. reesie having CBM showed high adsorption capacity on Avicel. Puchart et al. (2004) also showed 85% adsorption of β-mannanase from A. fumigatus IMI 385708 containing CBM1 onto cellulose.

Fig. 10.

Adsorption of APS1 mannanase on Avicel PH101. Equal amount of APS1 mannanase was mixed with different concentrations of Avicel for 1 h at 4 ℃ followed by separation of Avicel by centrifugation and measurement of remaining APS1 mannanase in supernatant

Resistance to proteases

Proteases are supplemented in food, feed and detergent industries (Kuddus and Ramteke 2012). Therefore, the activity of β-mannanase in such industries could be altered by proteases. For application of mannanases in food and feed industry, resistance to pepsin and trypsin is desirable. Residual activities of APS1 mannanase after treatment with pepsin and trypsin for 60 min at 37 ℃ were assessed. Purified mannanase retained 86% and 91% activity after exposure to pepsin and trypsin, respectively, whereas, partially purified and crude mannanase retained 100% activity. There are few protease-resistant mannanases reported (Luo et al. 2009; Regmi et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2012). This property of β-mannanase is suitable for its application in food and feed industry.

Conclusion

β-Mannanase from P. aculeatum APS1 produced under solid-state fermentation was purified by two-step chromatography technique, viz. ion exchange chromatography and gel permeation chromatography. APS1 Mannanase was characterized and identified by MALDI-TOF MS/MS analysis. The molecular weight of β-mannanase was found to be 40.6 kDa and it was identified as a member of GH5_7 family with CBM1. Biochemical characterization studies revealed good thermotolerance, protease resistance and stability in acidic conditions which are essential properties for applications in food and feed processing industries.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Central Instrumentation Facility (CIF) of IIT Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India, for providing protein sequencing and identification facility.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Research involving human and/or animal participants

This article does not contain any studies with human or animals participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable to the current research work as we have not used any human or animal subject.

Contributor Information

Purvi Bangoria, Email: bangoriapurvi1108@gmail.com.

Amisha Patel, Email: ami_111199@yahoo.com.

Amita R. Shah, Email: arshah02@yahoo.com

References

- Bangoria P, Divecha J, Shah AR. Production of mannooligosaccharides producing β-Mannanase by newly isolated Penicillium aculeatum APS1 using oil seed residues under solid state fermentation. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2021;34:102023. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2021.102023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A, Martin M-J, Orchard S, Magrane M, Ahmad S, Alpi E, Bowler-Barnett EH, Britto R, Bye-A-Jee H, Cukura A, Denny P, Dogan T, Ebenezer T, Fan J, Garmiri P, da Costa Gonzales LJ, Hatton-Ellis E, Hussein A, Ignatchenko A, Zhang J. UniProt: the Universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D523–D531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benech R, Li X, Patton D, Powlowski J, Storms R, Bourbonnais R, Paice M, Tsang A. Recombinant expression, characterization, and pulp prebleaching property of a Phanerochaete chrysosporium endo-β-1,4-mannanase. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;41(6–7):740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2007.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blibech M, Ghorbel RE, Fakhfakh I, Ntarima P, Piens K, Bacha AB, Ellouz Chaabouni S. Purification and characterization of a low molecular weight of β-mannanase from Penicillium occitanis Pol6. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;160(4):1227–1240. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8630-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan PS, Puri N, Sharma P, Gupta N. Mannanases: microbial sources, production, properties and potential biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(5):1817–1830. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deylami MZ, Rahman RA. Thermodynamics and kinetics of thermal inactivation of peroxidase from mangosteen (garcinia mangostana l.) Pericarp. J Eng Sci Technol. 2014;9(3):374–383. [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S, Kaur J. Microbial mannanases: an overview of production and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2007;27(4):197–216. doi: 10.1080/07388550701775919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djina Y, et al. Thermodynamics and kinetics of thermal inactivation of polyphenol oxidases and peroxidase of three tissues (Cambium, Central Cylinder, Internal Bark) of cassava roots (Manihot esculenta CRANTZ) varietie Bonoua 2, cultivated in Côte d’Ivoire. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2021;10(6):740–749. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2021.1006.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drula E, Garron M, Dogan S, Lombard V, Henrissat B, Terrapon N. The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D571–D577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felicia A, Onilude A. Production, purification and characterisation of a β—mannanase by Aspergillus niger through solid state fermentation (SSF) of Gmelina arborea shavings. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7(4):282–289. doi: 10.5897/AJMR11.1106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ge JP, Du RP, Zhao D, Song G, Jin M, Ping WX. Bio-chemical characterization of a β-mannanase from Bacillus licheniformis HDYM-04 isolated from flax water-retting liquid and its decolorization ability of dyes. RSC Adv. 2016;6(28):23612–23621. doi: 10.1039/C5RA25888J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzi H, Depagne C, Coradin T. Kinetics and thermodynamics of the thermal inactivation of polyphenol oxidase in an aqueous extract from Agaricus bisporus. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(1):500–506. doi: 10.1021/jf204104g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hägglund P, Eriksson T, Collén A, Nerinckx W, Claeyssens M, Stålbrand H. A cellulose-binding module of the Trichoderma reesei β-mannanase Man5A increases the mannan-hydrolysis of complex substrates. J Biotechnol. 2003;101(1):37–48. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(02)00290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid A, Rahman NA, Kalil MS. Enhanced mannan-derived fermentable sugars of palm kernel cake by mannanase-catalyzed hydrolysis for production of biobutanol Department of Chemical and Process Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Built School of Bioprocess Engineering, Universiti M. Bioresourc Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail SA, Hassan AA, Emran MA. Economic production of thermo-active endo β-mannanase for the removal of food stain and production of antioxidant manno-oligosaccharides. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2019;22:101387. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail SA, Khattab OKH, Nour SA, Awad GEA, Abo-Elnasr AA, Hashem AM. A thermodynamic study of partially-purified Penicillium humicola β-mannanase produced by statistical optimization. Jordan J Biol Sci. 2019;12(2):209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Jana UK, Suryawanshi RK, Prajapati BP, Soni H, Kango N. Production optimization and characterization of mannooligosaccharide generating β-mannanase from Aspergillus oryzae. Biores Technol. 2018;268:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.07.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuddus M, Ramteke PW. Recent developments in production and biotechnological applications of cold-active microbial proteases. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2012;38(4):330–338. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.678477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nat Publ Group. 1970;224:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H, Li S, Zheng H, Wei Z, Liu D, Raza W, Shen Q, Xu Y. A new acidophilic thermostable endo-1,4-β-mannanase from Penicillium oxalicum GZ-2: Cloning, characterization and functional expression in Pichia pastoris. BMC Biotechnol. 2014;14(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12896-014-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, et al. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;31:426–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Luo H, Shi P, Huang H, Meng K, Yang P, Yao B. A novel thermophilic endo-β-1,4-mannanase from Aspergillus nidulans XZ3: Functional roles of carbohydrate-binding module and Thr/Ser-rich linker region. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(5):2155–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H, Wang Y, Wang H, Yang J. Biotechnologically relevant enzymes and proteins a novel highly acidic β -mannanase from the acidophilic fungus Bispora sp. MEY-1: gene cloning and overexpression in Pichia pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;12:453–461. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Ma Q, Cai R, Zong Z, Du L, Guo G, Zhang Y, Xiao D. Effect of β-mannanase domain from Trichoderma reesei on its biochemical characters and synergistic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse. J Sci Food Agric. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31(3):426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyi O. Kinetic properties of purified β-Mannanase from Penicillium italicum. Br Microbiol Res J. 2014;4(10):1092–1104. doi: 10.9734/bmrj/2014/6555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palackal N, Lyon CS, Zaidi S, Luginbühl P, Dupree P, Goubet F, Macomber JL, Short JM, Hazlewood GP, Robertson DE, Steer BA. Biotechnologically relevant enzymes and proteins a multifunctional hybrid glycosyl hydrolase discovered in an uncultured microbial consortium from ruminant gut. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0645-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchart V, Vršanská M, Svoboda P, Pohl J, Ögel ZB, Biely P. Purification and characterization of two forms of endo-β-1,4-mannanase from a thermotolerant fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus IMI 385708 (formerly Thermomyces lanuginosus IMI 158749) Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2004;1674(3):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regmi S, Pradeep GC, Choi YH, Choi YS, Choi JE, Cho SS, Yoo JC. A multi-tolerant low molecular weight mannanase from Bacillus sp.CSB39 and its compatibility as an industrial biocatalyst. Enzyme Microbial Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren A, Reddy SK, Sjöberg JS, Aurelius O, Logan DT, Kolenová K, Stålbrand H. An Aspergillus nidulans β-mannanase with high transglycosylation capacity revealed through comparative studies within glycosidase family 5. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98(24):10091–10104. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5871-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidar A, Albuquerque ED, Voshol GP, Ram AFJ, Vijgenboom E, Punt PJ. Carbohydrate binding modules: diversity of domain architecture in amylases and cellulases from filamentous microorganisms. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8(July):1–15. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni H, Ganaie MA, Pranaw K, Kango N. Design-of-experiment strategy for the production of mannanase biocatalysts using plam karnel cake and its application to degrade locust bean and guar gum. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2015;4(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2015.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soni H, Rawat HK, Pletschke BI, Kango N. Purification and characterization of β-mannanase from Aspergillus terreus and its applicability in depolymerization of mannans and saccharification of lignocellulosic biomass. 3 Biotech. 2016;6(2):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0454-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PK, Kapoor M. Production, properties, and applications of endo-β-mannanases. Biotechnol Adv. 2017;35(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöver BC, Müller KF. TreeGraph 2: combining and visualizing evidence from different phylogenetic analyses. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CD, Li JF, Wei XH, Min R, Gao SJ, Wang JQ, Yin X, Wu MC. Fusing a carbohydrate-binding module into the Aspergillus usamii β-Mannanase to improve its thermostability and cellulose-binding capacity by in silico design. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TM, Scopes RK. The effects of temperature on the kinetics and stability of mesophilic and thermophilic 3-phosphoglycerate kinases. Biochem J. 1998;1095:1087–1095. doi: 10.1042/bj3301087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW and ClustalX. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2003 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0203s00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uechi K, Watanabe M, Fujii T, Kamachi S, Inoue H. Identification and biochemical characterization of major β-Mannanase in Talaromyces cellulolyticus Mannanolytic system. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2020;192(2):616–631. doi: 10.1007/s12010-020-03350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Luo H, Niu C, Shi P, Huang H, Meng K, Bai Y, Wang K, Hua H, Yao B. Biochemical characterization of a thermophilic β-mannanase from Talaromyces leycettanus JCM12802 with high specific activity. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(3):1217–1228. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5979-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zhang J, Wang Y, Niu C, Ma R, Wang Y, Bai Y, Luo H, Yao B. Biochemical characterization of an acidophilic β-mannanase from Gloeophyllum trabeum CBS900.73 with significant transglycosylation activity and feed digesting ability. Food Chem. 2016;197:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.10.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano JK, Poulos TL. New understandings of thermostable and peizostable enzymes. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14(4):360–365. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Mu BZ. Low-temperature-active and salt-tolerant β-mannanase from a newly isolated Enterobacter sp. strain N18. J Biosci Bioeng. 2016;121(2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young D, Ham S, Ju H, Cho H, Kim J, Kim Y, Shin D, Ha Y, Son K, Park H. Bioresource technology cloning and characterization of a modular GH5 b -1, 4-mannanase with high specific activity from the fibrolytic bacterium Cellulosimicrobium sp. strain HY-13. Bioresourc Technol. 2011;102(19):9185–9192. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, Zhang X, Wang Y, Na J, Ping W, Ge J. Purification, biochemical and secondary structural characterisation of β-mannanase from Lactobacillus casei HDS-01 and juice clarification potential. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;154:826–834. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.03.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Zhang R, Gao Y, Li J, Tang X, Mu Y, Wang F, Li C, Dong Y, Huang Z. Novel low-temperature-active, salt-tolerant and proteases-resistant endo-1,4-β-mannanase from a new Sphingomonas strain. J Biosci Bioeng. 2012;113(5):568–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.