Abstract

Introduction:

Adults 65 years of age or older with metastatic cancer face complicated treatment decisions. Few studies have explored the process with oncology clinicians during clinic encounters. Our exploratory study evaluated whether symptom burden or functional status impacted treatment decision conversations between older adults, caregivers, and oncology clinicians in a single National Cancer Institute within the Mountain West region.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted an observational, convergent mixed methods longitudinal study between November 2019 and January 2021; participants were followed for six months. The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) and Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (IADL) were administered prior to clinical encounter. Ambulatory clinic encounters were audio recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. Nineteen older adults with a metastatic cancer diagnosis or a relapsed refractory hematologic malignancy were approached to achieve a sample of fifteen participants. The main outcome of interest was the number and quality of treatment decision making conversations, defined broadly and encompassing any interaction between the participant and oncology provider that involved (a) an issue or concern (e.g., symptoms, quality of life) brought up by anyone in the room during the clinical encounter, (b) a clinician addressing the concern, or (c) the patient or caregiver making a decision that involved a discussion of their goals or treatment preferences.

Results:

Nine men and six women with a mean age of 71.3 years (6.6; standard deviation [SD]) were enrolled, and four died while on study. Participants were followed from one to ten visits (mean 4.5; SD 2.8) over one to six months. Of the 67 analyzed encounters, seven encounter conversations (10.4%) were identified as involving any type of treatment decision discussion. The seven treatment decision conversations occurred with five participants, all male (although female participants made up 40% of the sample), and 63% of participants who reported severe symptoms on the MDASI were female. Severe symptoms or functional status did not impact treatment conversations.

Discussion:

Our results suggest that older adults with incurable cancer and their oncology clinicians do not spontaneously engage in an assessment of costs and benefits to the patient, even in the setting of palliative treatment and significant symptom burden.

Keywords: Older adults, incurable cancer, treatment decision making, values, caregivers

Introduction

Adults 65 years and older are the largest group diagnosed with cancer in the United States; of the estimated 609,000 people who died from cancer in 2021, 70% were older adults.1,2 Treatment decisions for patients with incurable metastatic cancer is typically less straightforward than it is for curable, adjuvant treatment. This is especially true for older adults, who often begin the pathway of cancer treatment decision-making with comorbidities, sometimes multiple ones, which can increase as a result of cancer treatment.3,4 Additionally, because of their stage in life, older adults’ approach to evaluating the risks and benefits of cancer treatment differs from that of younger adults.5–7 Despite this, there is no standard assessment for older adults’ treatment goals or their individual values in relation to treatment options, even in metastatic disease when the goal of treatment is not curative. Geriatric assessment tools currently in clinical use, such as the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA),8,9 provide focused information on physical function, support, cognition, nutrition, and geriatric syndromes, but do not specifically investigate what is important to the older adult within the context of their cancer diagnosis and ensuing treatment choices. Consequently, oncology clinicians may not be able to integrate this information consistently into treatment decision conversations. As the number of older adults diagnosed with cancer reaches unprecedented numbers,10 there is a need to create systematic assessments to ensure value concordant decisions are made and to support individual level evaluation of the benefit and costs for the proposed treatment.

Although they represent the largest number of patients diagnosed with cancer, older adults are not well represented in clinical research.11,12 This is especially true for older adults with metastatic cancer.13 Treatment decision-making in older adults with metastatic cancer has not been well studied. However, previous research has identified that most older adults prefer to actively participate in health care decisions,14 and a few studies have attempted to explore their process of making cancer treatment decisions.15 One recent study used qualitative interviews to explore how older adults made their treatment decisions,15 and another used a mixed methods design to explore how functional impairment, comorbidities, and frailty were considered in the treatment decision process.16 However, to our knowledge, no previous studies have focused on cancer treatment decision making with older adults who have incurable cancer and followed those participants over time. Nor have previous studies examined the relationship between symptom burden and functional status in relation to treatment decisions made by older adults with incurable cancer.

Considerations for older adults in making cancer related treatment decisions include, but are not limited to, individual goals, life expectancy, quality of life, impact of symptoms (from treatment and cancer), as well as the preferences of their family and caregivers.17 To address the knowledge gap regarding what impacts the treatment decisions of older adults with metastatic cancer, we assessed symptom burden, functional status, and the number and focus of naturally occurring clinical conversations (between patients and clinicians) on treatment decision choices for non-curative cancer therapy. Specifically, our goal of this study was to describe the treatment-decision making process including conversations, and analyze whether patients’ symptoms, functional status, or values and preferences were elicited and integrated into the treatment discussions.

Methods/Design

Declaration

This observational, convergent, exploratory mixed-method prospective longitudinal study was reviewed by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board (IRB) and deemed exempt. Although our study was deemed exempt, informed consent is required by the IRB when it is reasonable and practical to do so. Written informed consent was obtained by all participants. While oncology clinicians were not consented, they were informed that their patient had been enrolled with a letter sent by e-mail. Participants were followed for six months and completed self-assessments of symptom and function prior to every ambulatory oncology visit. After completion of self-assessments, participants had a clinical encounter with their oncology clinician which was audio recorded. If participants transitioned to hospice, they were excluded from further survey assessments but their surveys and recordings prior to then were included. Before recording the clinical encounter, clinicians were reminded of their patient’s enrollment in the study by the study team member and often, also by the patient.

Quantitative Measures

Limited data exists on the determinants for quality of life in older adults with advanced cancer;18,19 however, some common symptoms have been identified and include pain, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea as well as an ability to perform activities of daily living independently or with minimal assistance. Consequently, the primary measures of interest were symptom burden, assessed with the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI), and functional status, assessed with the Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (Katz ADL). The MDASI contains thirteen symptom items found to have the highest frequency or severity in patients with cancer.20 Scored on a 0–10 severity range (mild, moderate, or severe) on daily functioning within the last 24 hours, the symptom assessment was paired with a functional assessment. The Katz ADL assessed functional status with a six-question self-administered survey of dependence or independence with bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence and feeding.21 Quantitative measures of self-reported patient symptoms and functional status were collected just prior to the clinical encounter.

Demographic variables were collected at the time of enrollment and included age, sex, race, ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, time since diagnosis, relationship status, sexual orientation, employment status, education, income, religion, family size, and if their financial situation was adequate to meet their needs. We hypothesized that these variables might influence the treatment decision conversations.

Qualitative Methodology—Transcribed Audio Recordings:

To better understand if participants described their symptoms and if those symptoms and functional status impacted clinical conversations, we audio recorded ambulatory oncology clinical encounter conversations between participants, their caregivers (if present), and oncology clinicians. Audio recording clinical encounters instead of conducting interviews emphasized naturalistic inquiry, capturing how patients and oncology clinicians communicated in a real-life setting.22 The research team also assessed to what degree (if any) that symptom burden or functional status influenced treatment discussions. Audio recordings were reviewed weekly and coded for treatment decisions. When a treatment decision occurred, including a pause in treatment, treatment change, or complete cessation of treatment, a follow up interview was conducted with the patient participant by the research team; it was audio recorded and transcribed similarly to clinical encounters. Treatment decision making conversations were defined broadly and encompassed any interaction between the participant and oncology provider that involved (a) an issue or concern (e.g., symptoms, quality of life) brought up by anyone in the room during the clinical encounter, (b) a provider addressing the concern, and (c) the patient or caregiver made a decision that involved a discussion of their goals or treatment preferences. If a treatment decision occurred, the research team noted what prompted the discussion, including who prompted the discussion (patient, caregiver, or clinician), and whether side effects from the treatment or the disease were considered in the conversation. Other components of treatment were evaluated, including additional treatment information offered, i.e., changing the frequency of infusions or a discussion of side effects. Discussions that were limited to stopping or continuing treatment with no additional discussion were coded as treatment binary options. Treatment discussions and their context were evaluated and counted.

Sample

Fifteen participants were recruited from ambulatory oncology clinics within a Mountain West National Cancer Institute designated cancer center between November 2019 and January 2021 and followed for six months. Eligible participants were identified by review of ambulatory clinic appointments and through the hospital discharge list. Enrolled participants received a $60 gift card at the time of enrollment and again at completion of the study. Inclusion criteria included age 65 years or older, metastatic cancer, or relapsed refractory hematologic malignancy. Participants were enrolled at any point during their treatment, including recently diagnosed as well as those who had received anti-cancer treatment for an extended time. Nineteen eligible participants were approached to arrive at the study goal of fifteen participants.

Data collection

After two participants were consented and enrolled, the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, resulting in a protocol change. Participants were still assessed at every ambulatory oncology clinic visit, but instead of an in-person survey prior to the appointment, they were asked symptom and functional status questions on the phone the day of their appointment. The in-person encounters between participants and oncology clinicians were still audio recorded, unless the planned ambulatory clinic visit was converted to a video visit or a telephone visit. Video or telephone visits occurred in six appointments (8% of total clinical encounters) over the course of the study.

Analysis

We analyzed the MDASI surveys for categories of symptom burden (mild, moderate, or severe) and the Katz ADL for changes in functional status within individual participants (present or not present). The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and de-identified; two study team members reviewed the transcripts for accuracy and to develop familiarity with the data prior to coding. We used content analyses to identify, enumerate and categorize the recorded clinical encounters and to identify treatment-decision making conversations. Initial codes included: (a) visit-specific information (i.e., reported symptoms or functional status changes, and discussion of laboratory results), (b) treatments, (c) discussions including goals of care, prognosis, and quality of life, and (d) emotions, e.g., psychosocial issues and coping. In addition to deductive codes—and because there were few treatment decision conversations identified initially—inductive codes were developed to identify patient clinician partnership categories and communication that may have affected treatment decision making. The codebook was developed from both these deductive and inductive approaches.

Throughout the independent review of the transcripts, the research team discussed differences in coding and with further discussion and analysis arrived at consensus. Initial intercoder agreement was measured with assessment of 15 percent of the transcripts. Because the agreement was only 42 percent, the research team double coded all transcripts and resolved initial conflict through further discussion. Upon completion, the research team reviewed coded excerpts from the clinical encounters and established categories based on higher-level topics that were evident across transcripts and captured meaningful concepts. Treatment decision conversations were separately analyzed to identify any correlation with demographics, malignancy type, duration of diagnosis, patient education, religious affiliation, or income. A joint display was created to facilitate integration and analysis of the quantitative and qualitative data.23,24 Data were analyzed using Dedoose (Version 8.3.45).25,26

Results

Nineteen individuals who met the eligibility criteria were approached, and fifteen participants were enrolled, nine (60%) men and six (40%) women. All enrolled participants self-identified as non-Hispanic White with one exception, a participant who identified as Asian. The mean age (standard deviation) of the participants was 71.3 years (6.6 SD). Participant characteristics are described in Table 1 (additional demographic information in Supplementary File 1). Demographic information on the four participants who declined enrollment were equivalent to the consenting participants. Malignancy subtypes varied (Table 1), as did the duration of diagnosis. Four (26.7%) of the enrolled participants died during the study, one immediately after transitioning to hospice and three while on active treatment. Participants were followed from one to ten visits (mean 4.5; SD 2.8) over one to six months. Sixty-eight conversations were recorded, and 67 analyzed; one clinical encounter was not able to be transcribed due to poor sound quality. Only one follow up interview was conducted after a participant transitioned to hospice.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics, Severe Symptoms, and Treatment Decisions

| ID | Age | Malignancy | Sex | Duration Diagnosis (years) | Total Visit Number | Treatment Decision Conversation | Severe Symptom on MDASI* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 71 | Glioblastoma† | Male | 4 | 1 | X | |

| 4 | 70 | Metastatic Salivary Gland† | Male | 15 | 3 | ||

| 5 | 65 | Acute Myelogenous Leukemia | Male | 3 | 2 | X | |

| 6 | 79 | Prostate† | Male | 1 | 1 | X | |

| 7 | 66 | Renal | Female | 1 | 9 | X | |

| 8 | 84 | BreastKATZ | Female | 1 | 6 | X | |

| 9 | 81 | Breast | Female | 3 | 3 | ||

| 10 | 68 | Ovarian | Female | 5 | 2 | X | |

| 12 | 79 | Metastatic Squamous Neck | Male | 3 | 2 | X | |

| 15 | 67 | Acute Myelogenous Leukemia | Male | 1 | 10 | X | |

| 16 | 66 | Myelofibrosis | Female | 1 | 4 | X | |

| 17 | 65 | Lung | Male | 2 | 6 | X | |

| 18 | 68 | Melanoma | Female | 1 | 6 | X | |

| 19 | 68 | Prostate | Male | 12 | 4 | X | |

| 21 | 73 | Acute Myelogenous Leukemia† | Male | 1 | 8 | X |

Severe symptoms defined as ≥7 on the MDASI scale (0–10);

Deceased during study; KATZ Positive for functional impairment on KATZ ADL

Abbreviations: MDASI, MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; ADL, activities of daily living

Treatment Decision Conversations

Because this study was conducted in an academic teaching environment, multiple clinicians interacted with participants during their clinical encounter, in total 23 clinicians participated in audio recorded encounters. These oncology clinicians included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. Of the 67 analyzed encounters, seven encounter conversations (10.4%) were identified as involving any type of treatment decision discussion. The seven treatment decision conversations occurred with five participants; two of the participants had two treatment decision conversations in different clinic visits with the same provider for both of their clinic visits (ID 12, ID 21). The seven treatment decision conversations were all conducted with male participants without severe symptoms on the MDASI, although female participants made up 40% of the sample, and 63% of female participants reported severe symptoms on the MDASI.

Treatment decision making conversations were not prompted based on the patient’s symptom burden (Table 1), but were prompted by the patient’s concern about next treatment steps (ID 21), the clinician addressing complexities of treatment with concurrent opportunistic infections (ID 21), and the clinician’s concern with acknowledging the patient’s “big picture” of treatment (ID 15, Table 2). In one encounter, the patient had been receiving treatment beyond what was supported by research, and the clinician juxtaposes the stories of a similar patient who had stopped treatment and one who had continued treatment; he then provided his own clinical recommendation to stop treatment but honored the patient’s decision to continue (ID 12, Visit 1). In another encounter (ID 17, Visit 4), the clinician recommends increasing the treatment dosage in response to the patient’s scans, but the patient recalls debilitating symptoms the last time he was on that dosage treatment. One conversation for another participant was clinician initiated, “I just don’t think we’ll probably ever be able to go on a higher dose for you because of your counts. So, hopefully this dose will keep the cancer at bay.” (Clinician, Participant 6, visit 4)

Table 2:

Treatment Decision Making Conversation Exemplar (ID 15, Visit 10)

| Clinician: Good to see you again. So, I know that I had seen you a couple of weeks ago, and I see you went through a few things. So, since we saw you, we saw that the blood counts are dropping slowly and that the blasts-- and not coming very fast, but still. So, we need to do something if you want, of course. The odds are not very favorable, but we feel that, given how we know you and of your interest in pursuing, I think it is a good option. But I think what I would like you also at some point is to think also, when will be-- when enough is enough, and this has to come from you, and you have to take into account really what you want yourself, and … ID 15: So… Clinician: … not necessarily what your wife or your children-- I think it’s really tough, because they want you there. They love you, but I think it is something which you have to consider also from your side. It’s not that I say you need to do so. I say that we should do so for all patients when something happens, but I would like to avoid giving more and more--then people say, “Oh, but the last months he was only treatment. He had only trials, and we forgot the big picture.” It’s still worth it, but I think it’s always good to give it a pause, even for five minutes, to make sure. ID 15: Yeah. I was just wondering if the trial-- if I start into the trial and I start getting real sick from it, can you just stop it? Clinician: You can always stop, by definition. ID 15: Because I didn’t want to … Clinician: But the point is it depends for what type of side-effects. Is it just because you feel weak, or is it just an obstacle? But if it’s really serious and if it is not reversible-- but what I would like to add outside of the trial-- so what we can do now is limited, because you have exhausted many treatments. You have progressed after transplant, we know, so the odds are not good, but in addition to what (Other Clinician) said, we have another option. It’s standard of care. It’s an agent you have not been exposed to, which is called Venetoclax. |

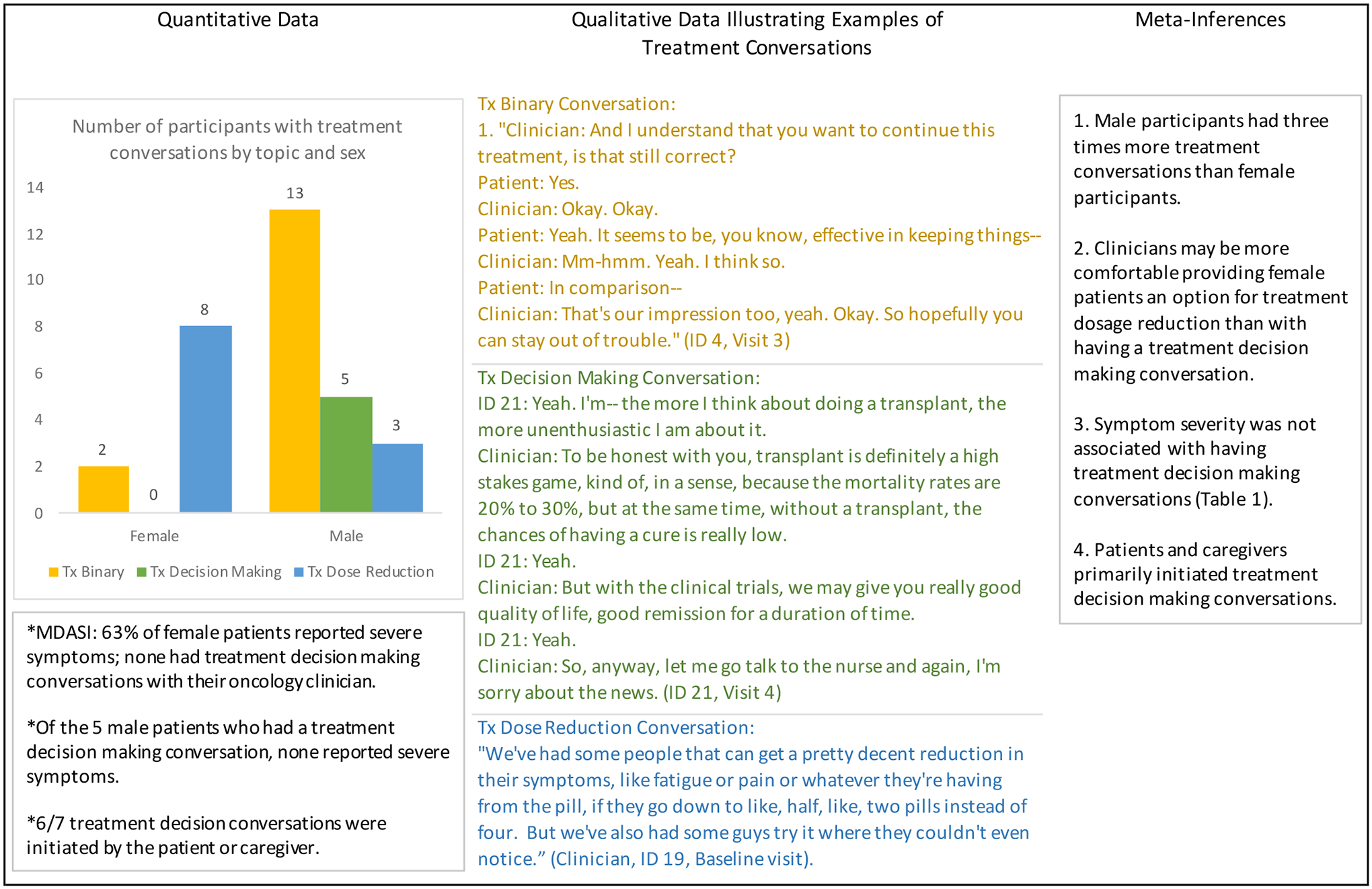

Further analyses of any treatment conversation (e.g., discussion of dose reduction, providing information about treatment options, or discussing binary options to stop or continue current treatment) revealed a trend toward male participants being engaged at a 3 to 1 ratio compared with female participants (Figure 1). Inexplicably, eight female participants had a conversation regarding dose reduction compared to three male participants.

Figure 1.

Qualitative Data Illustrating Examples of Treatment Conversations and Meta-Inferences

Abbreviations: MDASI, MD Anderson Symptom Inventory; Tx, treatment

Other notable findings were that most of the treatment decision conversations occurred with a caregiver present during the encounter. Three of the conversations were in direct response to a caregiver asking about prognosis, “You said the cancer seems to be stable. You have the markers, updated markers?” (Caregiver for Participant 8, visit 3). Three of the conversations were related to questions from the patient specifically about the symptom or treatment plan, “Is decreasing the dosage going to affect the cancer growth?” (Participant 8, visit 6) and, “Last night for some reason I was wondering if there are readily available survivor tables for someone like me.” (Participant 5, visit 2)

Disconnect between Symptoms and Treatment Discussions

Results from the symptom burden instrument, MDASI, indicated a range of symptom severity from mild (0 to 4) or moderate (5–6) to severe (≥7). Severe symptoms were defined within the MDASI as impacting relations with family and limiting patient’s enjoyment of life. Severe symptoms did not result in a treatment decision conversation in the subsequent audio recorded clinical encounters (Table 1). Except for one participant, all the participants had a score of 6 on the KATZ ADL (complete independent function); one participant had intermittent incontinence resulting in a score of 5 (still considered functionally independent). For the most part, functional status was not impacted, with one exception identified within Table 1. Our analysis of the 67 clinical conversations revealed that symptom burden was rarely reviewed within the clinical encounter. Clinicians sometimes discussed the overall scientific data for the treatment, providing statistical information from the original trials, but did not address symptoms specific to the patient. In addition, when patients and caregivers brought up aspects of treatment (e.g., frequency of infusions), the clinician did not use the opportunity to clarify the overarching purpose of the treatment (e.g., goal of care). Although symptoms were not correlated with treatment discussions, the most frequently reported and most severe symptom was fatigue, with 20% of symptom reports indicating severe fatigue.

We did not find patients’ values, preferences or choices elicited in our evaluation of the clinical encounters, though all participants had terminal cancer. Clinicians primarily addressed the technical aspects of treatment including timing of scans, biological markers used for surveillance of disease response to treatment, but did not address symptoms, treatment care preferences or assess the patient’s quality of life. Of the four participants who died during the study, two (50%) had conversations regarding treatment decisions just prior to death with a co-occurring change of treatment (cessation and transition to hospice). The other two participants died while on treatment and did not have any identified treatment decision discussions.

Discussion

We assessed symptom burden, functional status, and the number and focus of naturally occurring clinical conversations on treatment choices for non-curative cancer therapy. Although older adults make up most of the people diagnosed with metastatic cancer, no prior studies have evaluated treatment decisions with audio recordings to assess whether symptom burden and functional status were integrated into the clinical discussion. Audio recordings have been utilized as a component to promote informed patient decision making,27 and there are ongoing clinical trial studies evaluating the impact of sharing audio recorded clinic visits on older adults’ self-management.28 However, to our knowledge this is the first-time audio recordings of naturalistic conversations between clinicians and patients have been utilized to assess symptoms, functional status, and treatment decisions in patients with metastatic cancer.

In our analyses, multiple proximal decisions regarding treatment were identified, e.g., to continue treatment with questionable stability of disease or despite treatment toxicities, and without an assessment (or re-assessment) of goals of care. This was a surprising finding because all participants had incurable disease and, in some cases, were clearly experiencing significant symptoms without an overarching discussion of the purpose of the treatment or possible alternate interventions. Out of 67 of the recorded clinical conversations, only seven (10.4%) included some aspect of treatment decision making with five patients. The five patients who had recorded treatment decision making conversations did not report significantly higher symptom burden prior to these clinical encounters, nor did symptoms serve as a prompt for the treatment discussion. Instead, it was more common that the caregivers present drove many of these discussions. Of the seven clinical encounters, six conversations were prompted by the caregiver present, either in person, or on the phone listening to the clinical encounter.

Communication that involves caregivers in cancer decisions has not been well studied,29 but there is clear evidence that patients and caregivers desire participation in cancer treatment decision making and that involving caregivers in cancer treatment decisions reduces patient’s distress and increases their quality of life, satisfaction, and adherence to treatment.30,31 Our results highlight the potential value of a tool to focus and support clinicians in engaging in conversations that elicit patient values and preferences. Because of the study’s small sample size, it is difficult to draw any quantitative or qualitative conclusions regarding the impact of patient sex on the treatment decision conversations. However, it is interesting that there was no impact on the sex of the treating clinician in our analysis, and clearly this is an area that would benefit from further study.

Limitations

Because researchers were not privy to previous treatment discussions that occurred before our study began, those conversations may have pre-dated participant enrollment in the study. Additionally, the study was limited to capturing only scheduled ambulatory visits, and consequently there may have been treatment discussions in other settings (emergency department, telephone, etc.) that we were unable to capture. Two participants were enrolled in clinical trials during the study. Our analysis also identified some conversations that occurred between the participant and the caregiver when the provider was out of the room, which have not been included in our analyses given that the goals of the study and informed consent involved specific aims to identify the impact of patient symptoms and functional status on treatment decision conversations with their clinician. All the clinicians were informed of the study purpose, and consequently may have been more likely to engage in treatment decision making because they were aware that their clinical encounter was being audio recorded. The participant sample was limited to fifteen participants from a single site who were homogenous from a racial and ethnic standpoint, however, there was a wide range of education, income, and religious affiliation.

Conclusion

Even though all participants in our study were considered incurable and several participants reported severe symptom burden, there were no conversations recorded that involved end of life goals of care or focused on survival. One possible explanation for the few treatment decisions identified may have been because the clinician in the encounter assumed that the patient’s lack of initiating a conversation regarding pausing or stopping treatment endorsed their interest in treatment continuance. Few conversations occurred regarding how the patient’s symptoms fit into their overall treatment goals. Symptoms that could have been indicative of progression were not always investigated. Our results suggest that, without structured interventions within the clinical environment, older adults with metastatic cancer or relapsed refractory hematologic malignancies and their oncology clinicians do not spontaneously engage in an assessment of costs and benefits to the patient, even in the setting of significant symptom burden. A systemic approach to assessing what is important to these individuals within the context of their life may support a reflection of what they value in their decisions for treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to recognize Ms. Kimberly Brown for her support and work on this project.

Drs. Sarah Neller and Lorinda Coombs were supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32NR013456. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This study was partially funded by a grant from Maura C. Ryan, PhD, GNP Nursing Research Award and the American Nurses Foundation Funds.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Miller K & Jemal A Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(1):23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(17):2758–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams GR, Mackenzie A, Magnuson A, et al. Comorbidity in older adults with cancer. Journal of geriatric oncology. 2016;7(4):249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(4):337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Green E, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(20):2600–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawhney R, Sehl M, Naeim A. Physiologic aspects of aging: impact on cancer management and decision making, part I. Cancer journal. 2005;11(6):449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sehl M, Sawhney R, Naeim A. Physiologic aspects of aging: impact on cancer management and decision making, part II. Cancer journal. 2005;11(6):461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpato S, Guralnik JM. The Different Domains of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. In: Pilotto A, Martin FC, eds. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caillet P, Canoui-Poitrine F, Vouriot J, et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in the Decision-Making Process in Elderly Patients With Cancer: ELCAPA Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(27):3636–3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Dale W, et al. Cancer statistics for adults aged 85 years and older, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2019;69(6):452–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, et al. Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(1):78–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher KS, Hurria A. Under-representation of older adults in cancer registration trials: known problem, little progress. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(17):2036–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sedrak MS, Freedman RA, Cohen HJ, et al. Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: A systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(1):78–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chi WC, Wolff J, Greer R, Dy S. Multimorbidity and Decision-Making Preferences Among Older Adults. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(6):546–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bridges J, Hughes J, Farrington N, Richardson A. Cancer treatment decision-making processes for older patients with complex needs: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puts MT, Sattar S, McWatters K, et al. Chemotherapy treatment decision-making experiences of older adults with cancer, their family members, oncologists and family physicians: a mixed methods study. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017;25(3):879–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tariman JD, Berry DL, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp KG. Physician, patient, and contextual factors affecting treatment decisions in older adults with cancer and models of decision making: a literature review. Oncology nursing forum. 2012;39(1):E70–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daly LE, Dolan RD, Power DG, et al. Determinants of quality of life in patients with incurable cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(12):2872–2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors important to patients’ quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(15):1133–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhandiramge J, Orchard SG, Warner ET, van Londen GJ, Zalcberg JR. Functional Decline in the Cancer Patient: A Review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denzin NK, & Lincoln Y, ed The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. ed: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guetterman TC, Fàbregues S, Sakakibara R. Visuals in joint displays to represent integration in mixed methods research: A methodological review. Methods in Psychology. 2021;5:100080. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs—Principles and Practices. Health services research. 2013;48(6pt2):2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dedoose. Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. In. Version 8.3.45 Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. [computer program]. Version 8345. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon DH, Karthikeyan S, Chang A, et al. Mobile Audio Recording Technology to Promote Informed Decision Making in Advanced Prostate Cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(5):e648–e658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinicaltrials.gov. The Impact of Sharing Audio Recorded Clinic Visits on Self-management in Older Adults. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04344301. Published 2022. Accessed August 28, 2022, 2022.

- 29.Ellington L, Clayton MF, Reblin M, Donaldson G, Latimer S. Communication among cancer patients, caregivers, and hospice nurses: Content, process and change over time. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(3):414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, et al. Family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: A qualitative study of patient, family, and clinician attitudes and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(7):1146–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R, et al. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: A qualitative study. PloS one. 2019;14(3):e0212967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.