Abstract

The many-to-many hypothesis suggests that face and visual-word processing tasks share neural resources in the brain, even though they show opposing hemispheric asymmetries in neuroimaging and neuropsychologic studies. Recently it has been suggested that both stimulus and task effects need to be incorporated into the hypothesis. A recent study found dual-task interference between face and text functions that lateralized to the same hemisphere, but not when they lateralized to different hemispheres. However, it is not clear whether a lack of interference between word and face recognition would occur for other languages, particularly those with a morpho-syllabic script, like Chinese, for which there is some evidence of greater right hemispheric involvement. Here, we used the same technique to probe for dual-task interference between English text, Chinese characters and face recognition. We tested 20 subjects monolingual for English and 20 subjects bilingual for Chinese and English. We replicated the prior result for English text and showed similar results for Chinese text with no evidence of interference with faces. We also did not find interference between Chinese and English text. The results support a view in which reading English words, reading Chinese characters and face identification have minimal sharing of neural resources.

Keywords: Word processing, Perceptual expertise, Multilingual, Chinese, Object recognition

Introduction

Face recognition and visual word reading are the most studied examples of perceptual object expertise in humans. Both activate cerebral networks that include occipitotemporal regions, including the fusiform gyrus, an area linked to high-level visual processing (Weiner and Zilles 2016). One key distinction is that, while the face network is characterized by greater activity in the right hemisphere (Kanwisher et al. 1997), left-sided regions predominate for visual word processing (Cohen et al. 2002). This lateralization is partial, though, and imaging studies show that the voxels activated by faces overlap with those activated by visual words (Harris et al. 2016; Nestor et al. 2013).

This observation of structural overlap has led to the many-to-many hypothesis (Behrmann and Plaut 2013; Plaut and Behrmann 2011), which proposes that any given stimulus is processed by a network of many cortical areas, and conversely that any given cortical region is involved in processing many stimuli. Hence the specificity of object processing lies in patterns of network activation, rather than a ‘domain specificity’ of a cortical region, as modular accounts propose (Kanwisher 2000). In the case of faces and visual words, it is asserted that these processes both share and compete for neural resources during development, with sharing leading to overlapping patterns of activation on imaging, and competition leading to opposing lateralization (Plaut and Behrmann 2011).

One potential effect of two processes sharing at least some neural resources with finite capacity is that the simultaneous processing of both types of objects is less efficient than when either is processed alone or with a task that does not share those neural resources, an effect known as ‘dual-task interference’. For example, previous studies have demonstrated dual-task interference between face recognition and the perception of other object categories such cars and Gestalt line-stimuli (Cheung and Gauthier 2010; Curby and Gauthier 2014; Curby and Moerel 2019; Gauthier et al. 2003).

What about faces and visual words? The neuroimaging observation of overlapping regions of activation and the proposal that this indicates shared neural resources are grounds for believing that there might be dual-task interference between these two stimulus classes. However, faces and words are complex stimuli with multiple dimensions and properties. Mere activation on imaging does not tell us how the object is being processed by a given region or hemisphere. The ‘redundant’ and ‘equivalent’ views both suggest that the two hemispheres perform the same perceptual operations (Gerlach et al. 2014). The difference between these two views is the degree in which each hemisphere contributes to the operation. In the ‘redundant’ view, elimination of the minor hemisphere’s contribution does not lead to a deficit, while in the ‘equivalent’ view it causes a milder version of the deficit that arises from damage to the major hemisphere. In contrast to these two views, the ‘complementary’ view states that the two hemispheres perform different functions. Indeed, neuropsychological studies of face processing show that, while right fusiform damage impairs the identification of faces, leading to prosopagnosia (Davies-Thompson et al. 2014), left fusiform damage impairs lip-reading more than it does face identification (Albonico and Barton 2017; Campbell et al. 1986). Similarly, for text perception left fusiform damage causes pure alexia (Leff et al. 2006), but right fusiform damage impairs the identification of handwriting or font, rather than the ability to read (Barton et al. 2010; Hills et al. 2015).

The complementary view of hemispheric contributions led to predictions that dual-task interference may occur between face and word tasks that lateralize to the same hemisphere, but not between face and word tasks that lateralize to different hemispheres (Furubacke et al. 2020). Thus, there would be interference between visual word and lip reading, which both lateralize to the left hemisphere, and between handwriting and face identification, which lateralize to the right. On the other hand, there should be no interference between visual word reading and face identification, or between handwriting identification and lip reading. This pattern was indeed found (Furubacke et al. 2020), indicating that it is not just the stimulus but also the task that determines whether dual-task interference occurs. This finding, along with the neuropsychological data discussed above, has suggested a refinement of the many-to-many hypothesis that incorporates both stimulus and task factors in visual processing.

One important limitation of this prior study is that visual word stimuli were limited to the English language. Whether the findings would be true with other languages is not known. In particular, one might question whether the results would differ with languages like Chinese that have a morpho-syllabic script, rather than the alphabetic script of European languages. There are several lines of evidence that support this possibility. First, neuroimaging studies show that reading Chinese script recruits different neural resources than reading English, in particular involving right hemispheric regions. Two meta-analyses of functional MRI (fMRI) studies of writing systems have concluded that, while both alphabetic and Chinese languages share strong activation of the left fusiform gyrus, Chinese script also recruits fusiform or more posterior occipital regions in the right hemisphere (Bolger et al. 2005; Tan et al. 2005). Some fMRI studies have even found a right predominance of lingual/fusiform and parietal regions during Chinese processing (Tan et al. 2000, 2001). A cross-sectional study that compared adults with children found that learning Chinese led to greater increases in activation in the right middle occipital gyrus than did learning English (Cao et al. 2015). A multi-voxel pattern analysis showed that not only the left visual word form area but also the right fusiform face area showed good classification accuracy for Chinese characters, as well as for faces (Xu et al. 2012).

Second, there are related findings in studies using event-related potentials, which show more right-sided activation with Chinese script compared to English. One study found that the activity in the 100-200 ms period was mainly localized to the left occipital region with English words but bilateral with Chinese characters (Liu and Perfetti 2003). Another found that early potentials were similar between English and Chinese, but that later potentials between 250 and 350 ms showed more activity in the right lingual gyrus for Chinese (Qiu et al. 2008). What about studies comparing event-related potentials generated by faces and visual words? A recent meta-analysis of 24 such studies, including those with English, German or Chinese words (Nan et al. 2022) found that, in general, there were larger N170 amplitudes on the right for faces and on the left for words. While the meta-analysis did not contrast the results for different languages, the lateralization of N170 indices in the studies with Chinese characters were either only slightly left-biased (Cao et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2018) or sometimes even right-biased (Wang et al. 2011).

Third, there are behavioural results examining left/right biases. Chimeras with different halves can be used, and these show that, as with faces, the perception of Chinese characters show a left-side bias in experienced but not novice readers of Chinese (Hsiao and Cottrell 2009; Tso et al. 2014), which has been interpreted as a greater right hemispheric contribution to processing.

Such neuro-anatomic results converge on a conclusion that Chinese text involves right occipitotemporal resources more than English text does. This would indicate a greater potential for overlap with the face identity processing that occurs in right occipitotemporal cortex. If faces and Chinese text share neural resources, a logical question that follows is whether there is behavioural evidence that Chinese text shares some functional processing similarities with face identification. Unfortunately, no behavioural studies have directly compared whether different neural resources are involved in processing faces and English text versus faces and Chinese characters. Despite neuro-anatomic results suggesting that perceiving faces and Chinese characters may recruit similar brain regions, it is unclear whether there is any functional significance to this finding.

Perceptual studies suggest some parallels in how faces and Chinese words are processed. There is a longstanding proposal that faces are recognized holistically–that is, as indivisible wholes, rather than by their individual features–for review, see (Feizabadi et al. 2021; Piepers and Robbins 2012; Richler and Gauthier 2014). Experimental evidence for this comes from paradigms that show that processing of one facial region is influenced by other regions, as in the part-whole effect, in which individual face parts are better recognized when seen in the context of the whole face (Tanaka and Farah 1993; Tanaka and Simonyi 2016) and the composite-face effect, in which the recognition of one half of the face is influenced by the other half (Murphy et al. 2017; Young et al. 1987). In contrast, it is thought that written English words are processed by their individual components (Pelli et al. 2003; Rumelhart and McClelland 1982), though words too can show some influence of whole-word structure, as in the word-superiority effect, in which a letter is more likely to be identified when flashed as part of a word than a string of random letters (Feizabadi et al. 2021; Reicher 1969; Wheeler 1970). To date there are few studies of holistic processing of Chinese text. These have involved the composite-word effect, looking at whether the processing of one half of a word or character is influenced by the other half. While these studies found evidence of holistic processing for Chinese characters (Ren et al. 2021), some found this only for expert Chinese readers and not novices (Wong et al. 2012), while others have claimed the opposite (Chung et al. 2018; Hsiao and Cottrell 2009), sometimes limited only in the left hemifield of novices (Chung et al. 2018).

Altogether, the two observations that first, Chinese text may induce greater activation of the right ventral occipitotemporal cortex than English text, and second, that reading Chinese text may involve holistic processing, suggest that Chinese text could be more likely than English text to share neural resources with the processing of face identity. If so, Chinese text may show dual-task interference with faces that English text does not show. The aim of this study was to test this prediction. We examined two groups, novices and experienced readers of Chinese, for two reasons. First, there is uncertainty as to whether holistic effects for Chinese text processing are greater in novices or experienced readers (Chung et al. 2018; Hsiao and Cottrell 2009; Wong et al. 2012). Second, dual-task interference effects with faces have been shown to vary with the degree of expertise for the other object being alternated with faces (Curby and Gauthier 2014).

Methods

Participants

Fifty subjects were recruited online, 40 of whom met performance criteria (see below) that confirmed that they understood and executed the task correctly. Subjects completed a demographic questionnaire that asked about age, gender, hand preference, fluency in written English and Chinese (none, beginner, intermediate, fluent), and fluency with other written languages. The 40 subjects included 23 females, 2 left-handed and 2 ambidextrous subjects, and had a mean age of 25.3(s.d. 2.98, range 20–34) years. Twenty subjects had no experience with any written language other than English (9 men, 11 women, age range 20–34, mean = 25.2 years., s.d. 3.96 years). 20 subjects had experience with both written English and Chinese (8 men, 12 women, age range 23–29, mean = 25.3 years., s.d. 1.45 years) and categorized themselves as fluent in both. Of these, one subject indicated that they were intermediate or fluent in one or more languages besides English and Chinese. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were reimbursed $10 for their time. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health, and all subjects gave informed consent in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Stimuli

Four categories of stimuli were used: faces, visual words from English, visual words from Chinese, and colored ellipses (Fig. 1). Face stimuli were 400 pictures of 25 female and 25 male models, all Caucasian, with ages ranging from 18 to 30 years old, with 8 facial expressions (angry, contemptuous, disgusted, fearful, happy, neutral, sad, surprised) for each model. Pictures were taken using a Nikon d3300 camera under consistent lighting conditions with a white background at a distance of one meter between the model and the camera. Photographs were converted to greyscale with the background removed in Adobe Photoshop CC 2019 (www.adobe.com) and placed in an elliptical frame to exclude external features such as the head and neck. The final elliptical images had a short horizontal axis of 272 pixels and a long vertical axis of 365 pixels. The test was conducted virtually, in full-screen mode and calibration was done through our online software to ensure that the size of the stimuli remains constant. However, as the test was done online, viewing distances was not controlled precisely.

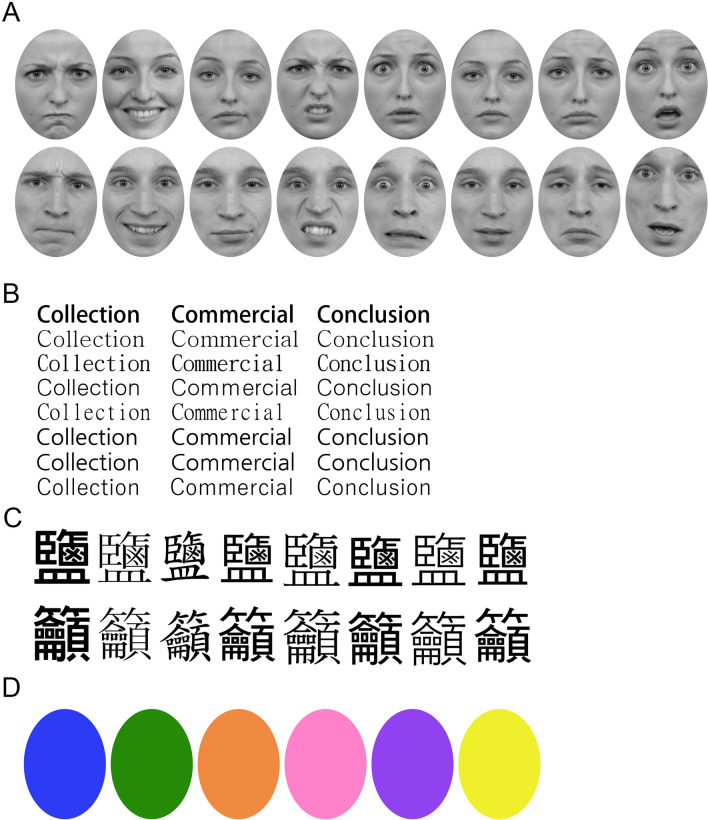

Fig. 1.

Examples of stimuli used in the alternating dual-task experiment. A 8 different facial expressions in two examples of different face identities. B 8 different fonts in three examples of different English word identities. C 8 different fonts in two examples of different Chinese character identities. D 6 different colored ellipses

Visual word stimuli were ten words each from the English and Chinese language. All English words were ten-letter words, and Chinese characters had an average of 21.8 strokes (s.d. = 3.7) each. Chinese characters were chosen from the Hong Kong, Mainland China & Taiwan Chinese Character Frequency Database (http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/chifreq/). English words and Chinese characters were matched for frequency of appearance (mean English word occurrence = 69.7/million (s.d. = 17.3), mean Chinese character occurrence = 69.8/million (s.d. = 14.4), English words were presented in size 18 font, using 8 different styles (Adobe Fan Heiti Std, Dotum, MingLiU, MalgunGothic NanumGothic, YuGothic, Batang, DFKai-SB). Chinese characters were presented in size 48 fonts, using the same 8 different styles as the English words. Single word stimuli were centered on a rectangular transparent background in Adobe Photoshop CC 2019. The final pictures spanned about 1200 by 300 pixels.

Baseline stimuli were six solid ellipses of different colors (yellow, orange, green, pink, blue, purple) created in Adobe Photoshop CC 2019, identical in shape and size to the elliptical frames used for the face stimuli.

Procedure

The experiment was conducted in a virtual on-line format in accordance with public health guidelines regarding COVID-19 at the time. TESTABLE (www.testable.org) was used to construct and deliver the experiments for participants to complete at home after the screening questionnaire. The experimental procedure (Fig. 2) used an alternating dual-task interference method previously used by our group (Furubacke et al. 2020) and others (Curby and Gauthier 2014; Gauthier et al. 2003) to study object processing.

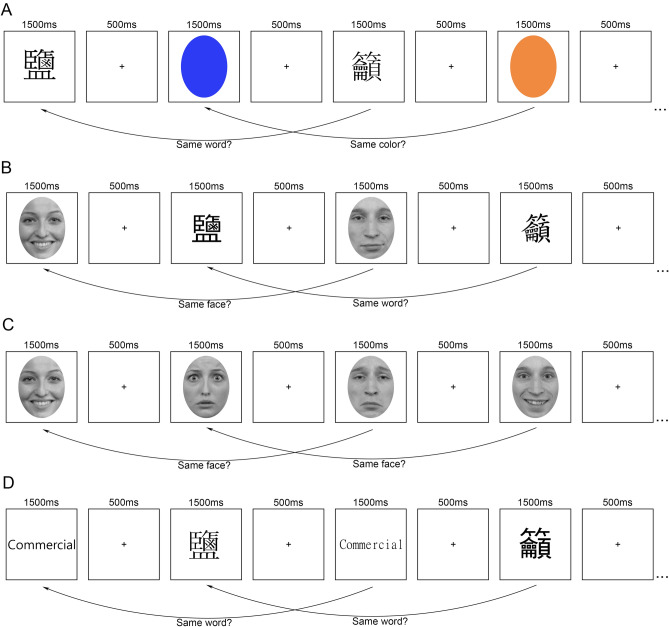

Fig. 2.

Examples of alternating dual-task experimental trials. A Baseline trials: colors with faces/words. Target task was either visual word/face identity recognition or color recognition. B Face/word trials: target task was either face identity recognition or visual word identity recognition. C Similar trials: faces with faces or words with words. Target task was the same within a block. D Word/word trials: English words with Chinese characters. Target task was English or Chinese character identity

Participants were first shown a demonstration of six stimuli for 4000 ms each, with an inter-stimulus interval of 1500 ms during which a central cross (30 × 30 pixels) on a transparent background was shown. The stimuli were accompanied with text explanations of what a correct response would be in order to familiarize participants with their instructions. No response from the participants was required on these demonstration trials.

Next, subjects had a practice block of 15 trials. In each practice trial, participants were shown either a face or a word for 1000 ms, and then an interstimulus interval showing the central cross for 1500 ms. The sequence of trials alternated between English words and faces. The participant’s task was to press the spacebar if the currently stimulus was the same as that shown two trials prior. The interleaving of face and word trials meant that subjects had to keep track of faces and words simultaneously. After each practice trial, subjects received feedback about the accuracy of their response.

After the practice block, participants performed nine experimental blocks, each with 100 trials, in random order. Within each block a trial presented a visual stimulus for 500 ms, followed by an interstimulus interval showing a central fixation cross for 1500 ms. Even-numbered trials presented stimuli from one stimulus class, and odd-numbered trials stimuli from a second stimulus class. The subjects’ task was to indicate by keypress whether the current stimulus was the same or different as the stimulus shown two trials before. This interleaving design meant that subjects had to keep track of two stimuli at the same time: the one from the penultimate trial for comparison with that in the current trial, and the one from the immediately preceding trial for comparison with that of the next trial (Fig. 2). For Chinese and English text, the question was whether the two were the same words, regardless of font, while for the faces the question was whether the two images were of the same person, regardless of facial expression.

Three blocks alternated the coloured ovals with one of the three other stimulus classes, namely faces, English words, or Chinese characters (e.g., Fig. 2A). These were considered ‘baseline conditions’, in that we expected that there would be minimal overlap in processing resources between colour and either face or word processing. Hence this condition would control for general factors involved in dual task performance. Four blocks alternated between the same class of stimuli: i.e., English words alternating with other English words, Chinese characters with other Chinese characters, faces with other faces, and colours with other colours. These ‘similar conditions’ would be expected to general maximal dual-task interference (Fig. 2C). The two key experimental blocks to address our hypothesis alternated faces with either English or Chinese characters (Fig. 2B). Our prior study found no dual-task interference between English word reading and face identification, and the first of these two blocks aimed to replicate that result. The second of these two blocks addressed the key question, whether dual-task interference occurred between Chinese character reading and face identification. Finally, one block alternated English words with Chinese characters (Fig. 2D), to see if dual-task interference occurred between the two different texts, which would point to some sharing of neural substrate between English word and Chinese character processing.

Since responses required participants to compare currently shown stimuli to those that were shown two trials before, no response was expected for the first two trials of each block. Stimuli for the first two trials were chosen randomly, while stimuli for the rest of the 98 trials were chosen in a pseudo-random fashion so that there were equal number of ‘same’ and ‘different’ trials. The ordering of stimuli was also constrained so that on ‘same’ trials the two faces differed in facial expression or the two words differed in font, to minimize matching by low-level image properties rather than by object recognition.

Analysis

Chance performance is 50% and by binomial proportions, with 49 trials per task, the upper 95% limit of chance performance is 61%. We used this 61% cut-off on color trials as a measure of participants’ ability to understand and execute the task. This excluded ten of the 50 subjects, resulting in the final samples of 20 monolingual and 20 bilingual participants. Network connection problems led to the loss of the reaction time data of one bilingual subject.

Responses to the colored ellipses were considered irrelevant to the aims of the study, in which were to investigate interference effects between visual word or face processing.

We analyzed the responses to faces and words separately. Face accuracy, discriminative sensitivity (d’), and response times to faces were analyzed with a repeated-measures ANOVA with interference condition (colours/baseline, faces/similar, English words, Chinese characters) as a within-subject factor, and group (English monolinguals, Chinese/English bilinguals) as a between-subject factor.

For visual word accuracy, we conducted repeated measures ANOVAs on accuracy and response times, with language (English, Chinese) and interference condition (word/colour baseline, face/word, other language, similar) as within-subject factors, and group (English monolinguals, Chinese/English bilinguals) as a between-subject factor.

For all analyses, significant differences were explored by Bonferroni post-hoc multiple comparisons (corrected p-values are reported), and effect sizes estimated with partial eta-squared (η2).

Results

A. Face performance

I. Accuracy. Repeated-measures ANOVA found a main effect of interference condition (F(3,114) = 31.46, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.453; see Fig. 3). Pairwise contrasts showed that face accuracy was worse for the face/face (similar) condition (mean 0.659, s.e. 0.013) than for the face/colour (baseline) condition (0.795, s.e. 0.011, p < 0.001), as expected. The face/English words condition had better accuracy than the face/face condition (0.785 s.e. 0.017; p < 0.001) but did not differ from the face/colour (baseline) condition (p = 0.998). This replicates the finding of Furubacke et al. (2020), that English word reading and face identification do not show dual-task interference. How about the key face/Chinese characters condition? This was also better than the face/face condition (0.773, s.e. 0.015, p < 0.001) and did not differ from the face/colour (baseline) condition (p = 0.936) (Fig. 3A). Of note, it also did not differ from the face/English words condition (p = 0.996).

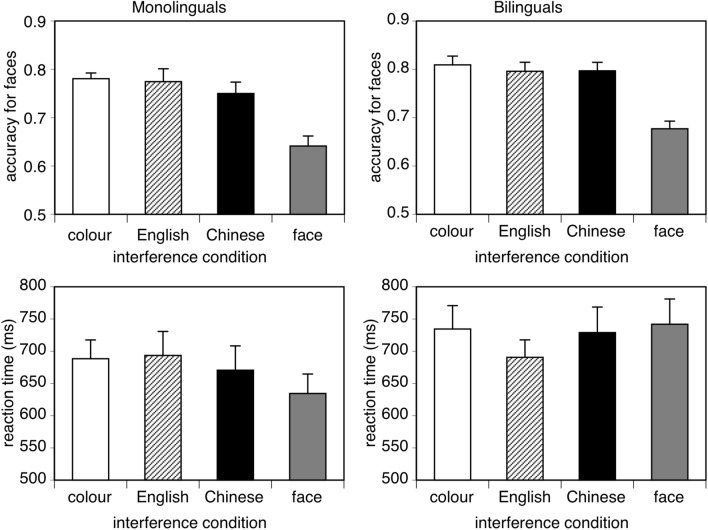

Fig. 3.

Results for face identity recognition. In these and all subsequent graphs of results the baseline condition is the white bar on the left and the maximal interference condition the grey bar on the right, with conditions of interest in the middle. Top: accuracy when the alternating ‘interfering’ stimuli were colors (the baseline condition). English words, Chinese characters, or other faces (the ‘similar’ condition with maximal interference). Bottom: reaction times. Error bars show the standard error. Horizontal lines show pair-wise contrasts that were significant

There was no significant main effect of group (F(1,38) = 2.58, p = 0.116, η2 = 0.064) or interaction between group and interference condition (F(3,114) = 0.23, p = 0.874, η2 = 0.006). Hence there is no interference on face accuracy from either Chinese or English word processing, regardless of whether the subject is a novice or expert in Chinese.

ii. Discriminative sensitivity (d’). Repeated-measures ANOVA found similar results as the analysis of accuracy. There was a main effect of interference condition (F(3,114) = 23.55, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.383). Pairwise contrasts showed that d’ for the face/face (similar) (0.904, s.e. 0.075) was lower than the d’ of all other conditions (baseline 1.907, s.e. 0.107; face/English 1.970, s.e. 0.152; face/Chinese 1.904, s.e. 0.141; all ps < 0.001)., while the other conditions were comparable to each other.

As for accuracy, there was no significant main effect of group (F(1,38) = 1.80, p = 0.188, η2 = 0.045) or interaction between group and interference condition (F(3,114) = 0.27, p = 0.849, η2 = 0.007).

iii. Response times. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of interference condition (F(3,111) = 4.71, p < 0.005, η2 = 0.113; see Fig. 3). Response times for faces were faster for the face/colour (baseline) condition (mean 626 ms, s.e. 21 ms) than the face/face condition (688 ms, s.e. 25 ms; p < 0.005), confirming an interference effect. The face/English words condition did not differ from either the baseline condition (652 ms, s.e. 20 ms; p = 0.593) or the face/face condition (p = 0.565). The face/Chinese characters condition also did not differ from either the baseline condition (671 ms, s.e. 26 ms; p = 0.056) or the face/face condition (p = 0.998), and also did not differ from the face/English words condition (p = 0.847). The interaction between group and interference condition was significant (F(3,111) = 3.66, p < 0.0,, η2 = 0.090), as monolinguals (634 ms, s.e. 34 ms) were faster than the bilinguals (742 ms, s.e. 35 ms) in the face/face condition alone (p = 0.035). There was no significant main effect of group (F(1,37) = 1.38, p = 0.248, η2 = 0.036) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tests for equivalence

| Condition | Subject group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Interference | Monolingual | Bilingual |

| Face | English | 0.021 | 0.026 |

| English | Face | < 0 | 0.021 |

| Face | Chinese | 0.044 | 0.025 |

| Chinese | Face | 0.009 | 0.019 |

| English | Chinese | < 0 | 0.011 |

| Chinese | English | < 0 | 0.036 |

B. Visual word performance

I. Accuracy. The ANOVA revealed a main effect of language (F(1,38) = 33.02, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.465) and group (F(1,38) = 34.26, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.474): overall accuracy was higher for the bilingual speakers (0.891, s.e. 0.015) than the monolingual ones (0.765, s.e. 0.015), and for English words (0.857, s.e., 0.012) than Chinese ones (0.798, s.e., 0.012) (Fig. 4). There was a significant interaction between language and group (F(1,38) = 101.91, p < 0.001 η2 = 0.728). As expected, bilingual participants were far more accurate with Chinese characters (0.913, s.e. 0.016) than monolinguals (0.683, s.e. 0.017; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B), while there was no difference in accuracy for English words between bilingual and monolingual subjects (p = 0.332).

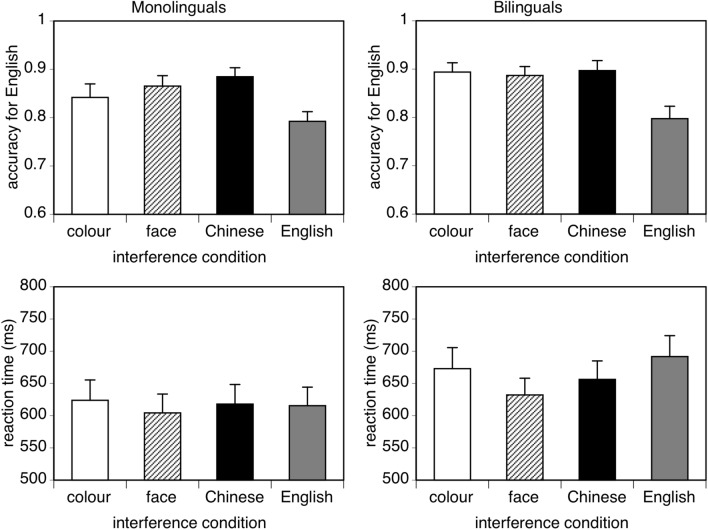

Fig. 4.

Results for English word reading. Top: accuracy when the alternating ‘interfering’ stimuli were colors, faces, Chinese characters, or other English words. Bottom: reaction times. Error bars show the standard error. Horizontal lines show pair-wise contrasts that were significant

Because of the asymmetry in groups in respect to the stimuli (both groups know English, but only the bilinguals know Chinese), we ran two separate ANOVAs, one for English words and one for Chinese characters, both with subject language group as a between-subject factor. For English words, the four interference conditions were English/colour (baseline), English/English, English/face and English/Chinese. For Chinese characters, the four interference conditions were Chinese/colour baseline, Chinese/Chinese, Chinese/face and Chinese/English.

For English words (Fig. 4), accuracy showed no main effect of group (F(1,38) = 0.97, p = 0.332, η2 = 0.025), or interaction with group (F(3114) = 0.69, p = 0.569, η2 = 0.018 (Fig. 4A). There was an effect of condition (F(3114) = 11.77, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.237). The English/English condition (mean 0.795, s.e. 0.017) was less accurate than all other conditions (English/colour 0.868, s.e. 0.017; English/face 0.876, s.e. 0.015; English/Chinese 0.891, s.e. 0.014; all ps < 0.001). In particular, there was no difference between the English/face condition and the English/colour baseline (p = 0.996), replicating our prior result. Also, there was no difference between the English/Chinese condition and the English/colour baseline (p = 0.989), suggesting that there is also no interference from Chinese on English text processing.

For Chinese characters (Fig. 5), the main effect of group was significant (F(138) = 86.89, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.696), because of the higher accuracy of bilinguals (0.913, s.e. 0.017) compared to monolinguals (0.683, s.e. 0.017). The main effect of interference condition was significant too (F(3114) = 5.32, p < 0.005, η2 = 0.123), showing that word accuracy was worst in the Chinese/Chinese (0.751, s.e. 0.015) condition compared to the other three (Chinese/colour 0.813, s.e. 0.018; Chinese/face 0.814, s.e. 0.015; Chinese/English 0.816, s.e. 0.20; all ps < 0.05), which in turn did not differ among each other (Fig. 4B). Importantly, there was no interaction between group and interference condition (F(3114) = 1.15, p = 0.332, η2 = 0.029). Planned linear contrasts showed that there was no difference between the colour/Chinese baseline conditions and the face/Chinese conditions for either monolinguals or bilinguals (respectively, p = 0.998 and p = 0.999), indicating no evidence of interference from English on Chinese text processing. Accuracy in the face/Chinese condition was better than that for the Chinese/Chinese condition, for monolingual (p = 0.004) but not bilingual subjects (p = 0.401).

Fig. 5.

Results for Chinese character reading. Top: accuracy when the alternating ‘interfering’ stimuli were colors, faces, English words, or other Chinese characters. Bottom: reaction times. Error bars show the standard error. Horizontal lines show pair-wise contrasts that were significant

ii. Discriminative sensitivity (d’). The ANOVA revealed a main effect of language (F(138) = 6.02, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.137) and group (F(138) = 34.19, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.508): with d’ greater for bilingual (3.078, s.e. 0.138) than monolingual readers (1.860, s.e. 0.138), and greater for English (2.584, s.e., 0.108) than Chinese words (2.354, s.e., 0.108). There was a significant interaction between language and group (F(138) = 89.53, p < 0.001 η2 = 0.702), with the expected finding that d’ for Chinese characters was greater for bilingual (3.406, s.e. 0.153) than monolingual readers (1.301, s.e. 0.153; p < 0.001), but no difference between these subjects in d’ for English words (p = 0.134).

The ANOVA limited to English words showed an effect of condition (F(3114) = 12.94, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.254). The d’ for the English/English condition (mean 1.912, s.e. 0.129) was lower than the d’ of all the other conditions (English/colour 2.712, s.e. 0.172; English/face 2.720, s.e. 0.153; English/Chinese 2.990, s.e. 0.165; all ps < 0.001).

The ANOVA limited to Chinese words produced similar results with a significant main effect of the interference condition (F(3114) = 4.901, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.114), with the Chinese/Chinese condition having lower sensitivity than all the other conditions (Chinese/colour 2.476, s.e. 0.154; Chinese/face 2.545, s.e. 0.136; English/Chinese 2.514, s.e. 0.189; all ps < 0.05). As expected, the main effect of subject group was significant (F(138) = 95.19, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.715), with bilingual speakers (3.406, s.e. 0.153) having a higher d’ for Chinese than the monolingual speakers (1.301, s.e. 0.153).

iii. Response times. The ANOVA revealed only a significant interaction between language and group (F(135) = 15.78, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.311), showing that monolinguals had longer response times for Chinese (645 ms, s.e. 30 ms) compared to English words (602 ms, s.e. 26 ms; p < 0.001), while the bilinguals did not (641 ms, s.e. 29 ms, and 663 ms, s.e. 26 ms, respectively; p = 0.063).

C. Equivalency testing

Our accuracy data provided the most consistent demonstration of dual-task interference, with poorer performance in (similar) conditions, which we postulated would generate maximal interference, versus (baseline) conditions, which should have minimal interference. In the key experimental condition, blocks mixing Chinese and faces had significantly less interference than the relevant maximal interference conditions. Also, both the blocks mixing written text and faces did not differ from the baseline conditions. Because the latter are null results, though, they cannot prove that there is no interference. Rather one can use tests for equivalence (Streiner 2003) to estimate the 95% upper limit for the reduction in accuracy compatible with our results, for various interference conditions. These show estimates ranging from less than zero to a 4% absolute decrease in accuracy (Table 1).

Discussion

Our paradigm was able to show dual-task interference when tasks alternated between stimuli of the same category (i.e., face/face, Chinese/Chinese, English/English), compared to a baseline of alternation with a task that likely had minimal sharing of neural resources, namely colour processing. With this method we replicated our previous finding of a lack of dual-task interference between English word and face identification (Furubacke et al. 2020). For our key question, we did not find dual-task interference between the reading of Chinese characters and face identification, in either novice or experienced readers of Chinese. Finally, we also did not find dual-task interference between the reading of Chinese and English text. The lack of interference between reading English text, reading Chinese characters, and face identification suggests that these three visual processes have minimal overlap in neural resources.

The hypothesis that reading of Chinese characters might show dual-task interference with face identification was based on evidence from neuro-imaging (Bolger et al. 2005; Tan et al. 2005), electrophysiological (Liu and Perfetti 2003; Wang et al. 2011), and tachistoscopic work (Hsiao and Cottrell 2009; Tso et al. 2014), that reading Chinese characters appears to recruit right hemispheric resources more than does the reading of English text. While there is substantial evidence that face identification is also lateralized to the right hemisphere, it does not necessarily follow that Chinese reading and face identification use the same neural substrates. First, the anatomic resolution of event-related potential studies using electroencephalography is poor. Second, tachistoscopic studies provide only indirect inferences about which hemisphere may be preferentially involved in a task, not which region. Third, even if the better spatial resolution of MRI allows it to show that both words and faces activate regions in the fusiform gyrus, these regions are overlapping but not identical (Harris et al. 2016; Nestor et al. 2013). Even within overlapping regions, each MRI voxel contains several million neurons (Georgiou 2014), and activation studies cannot clarify whether the subset of neurons in a voxel that is activated by one task is the same subset that is activated by a second.

Hence other techniques are needed to address the question of whether word and face processing share resources. Adaptation studies can be helpful: if the response to a stimulus is reduced by prior exposure to another, this suggests that the processing mechanisms for the later stimulus were also engaged by the preceding stimulus. While event-related potentials such as the N170 may have poor anatomic resolution, its adaptation response to repeated stimuli of different categories can be a clue as to whether perception of the different items share neural resources. A study using event-related potentials found that the amplitude of the N170 response to Chinese characters was reduced not only by prior exposure to Chinese characters, as expected, but also by prior exposure to faces (Cao et al. 2014). Curiously, though, it did not find the reverse, an adaptation of the response to faces by prior exposure to Chinese characters. As yet, we are not aware of a similar study of cross-category adaptation effects between English reading and face perception.

Also useful are neuropsychological studies that examine word and face processing in the same patients, particularly those with focal lesions. Indeed, two of the predictions of the many-to-many hypothesis were that prosopagnosic subjects would have minor reading deficits and alexic subjects would have milder face recognition problems (Behrmann and Plaut 2013). While one study suggested this was the case after acquired lesions (Behrmann and Plaut 2014), subsequent studies have not found consistent evidence of reading deficits in patients with acquired (Hills et al. 2015; Susilo et al. 2015) or developmental prosopagnosia (Rubino et al. 2016; Starrfelt et al. 2016). While an Icelandic study found some face recognition deficits in subjects with developmental dyslexia (Sigurdardottir et al. 2021), lip-reading is more significantly affected than face identification in patients with acquired alexia (Albonico and Barton 2017). We are not aware of similar neuropsychological studies of face recognition and Chinese reading.

Our prior study (Furubacke et al. 2020) of dual-task interference between text and face processing was motivated by these neuropsychological observations, that patients with left fusiform lesions had problems with reading text and lip-reading (Albonico and Barton 2017; Campbell et al. 1986), while those with right fusiform lesions had problems with identifying textual styles and recognizing faces (Hills et al. 2015). We found evidence of interference between faces and English words only if the required tasks localized to the same hemisphere, as inferred from the neuropsychological data, and not if they localized to different hemispheres. The current study replicates and extends these findings by showing that neither English nor Chinese reading show dual-task interference with face recognition, despite the evidence that reading Chinese characters may recruit more right hemispheric resources than reading English (Bolger et al. 2005; Hsiao and Cottrell 2009; Tan et al. 2005; Tso et al. 2014).

Although language interactions were not the primary focus of our study, we also did not find evidence of dual-task interference between Chinese and English in our bilingual subjects. This may seem surprising, given that there is considerable evidence for various cross-language effects in bilingual subjects. For example, there are language interactions in phonetics (Antoniou et al. 2011), and interference in syntax during simultaneous translations of auditory sentences, also shown between Chinese and English (Ma and Cheung 2020). For written language, older Chinese-English studies also tended to focus on cross-language syntactical effects (Lay 1975).

Less is known about cross-language orthographic interactions. One Spanish/English study found inhibitory effects when bilingual subjects made semantic judgments about inter-lexical homographs–i.e. words having the same orthography in both languages, such as < pie > , which means foot in Spanish (Macizo et al. 2010). Given the different script systems, there are no inter-lexical homographs between Chinese and English. Nevertheless, there are two implicit priming studies that have looked at interactions between Chinese and English text as bilingual subjects judging the semantic relationship of pairs of English words. In one, reaction times were prolonged if the corresponding Chinese characters for the pair had components that were identical in both sound and visual form (Thierry and Wu 2004). This interference was found only when the English words were not semantically related. The behavioral interference was accompanied by modulation of the later N400 potential rather than the earlier peaks in occipital cortex. In a second study these same investigators separated the effects of sound and visual form in Chinese (Wu and Thierry 2010). They found a significant priming effect if the corresponding Chinese text shared similar sounds, but not when they shared similar characters, indicating cross-language interactions in phonology but not orthography. Such results are consistent with the lack of interference between markedly different orthographic systems of Chinese and English that we observed. It would be of interest to see if this would also be true of languages that have a common script, such as English and French.

The fact that blocks mixing faces with Chinese or English text showed significantly better accuracy than blocks with maximal interference (face/face, English/English, or Chinese/Chinese) indicates that there is at most only partial dual-task interference between face identity and either Chinese or English text processing. A limitation of our study is that, as null results, the non-significant differences when comparing to the baseline conditions cannot prove that there is no dual-task interference between Chinese or English text and face identity processing. Our tests for equivalency suggest that, on average, there is at most a 2% decline in absolute accuracy under dual-task conditions. However, the magnitude of maximal interference in our study is modest, ranging from 6–7% for language responses to 14% for face responses. Hence, we caution that a small degree of dual-task inhibition cannot be excluded.1 Further studies with techniques that yield larger cross-category interactions would be helpful in examining this further.

Other potential limitations include the fact that we did not study Chinese monolinguals. Given the evidence that the neural architecture of bilingual subjects may differ from that of monolingual subjects (Hayakawa and Marian 2019), one cannot exclude the possibility that Chinese monolinguals may show different results from our Chinese bilingual subjects, in terms of interactions between face and Chinese text processing. Also, while all of our bilingual subjects reported themselves to be fluent in Chinese, fluency may still contain a spectrum of proficiency that could be fractionated using educational assessment instruments (e.g. the Chinese Proficiency Grading Standards for International Chinese Language Education, https://www.blcup.com/EnPInfo/index/10865#001). Nevertheless, given the controversy over whether holistic processing is more characteristic of expert Chinese readers (Wong et al. 2012), or novices (Chung et al. 2018; Hsiao and Cottrell 2009), an important aspect of our study was that we included both types of subjects, and found no interference in either. Third, one could explore tachistoscopic presentation in one hemifield. One study has suggested that novices show composite effects in the left but not the right visual field (Chung et al. 2018). Coupled with the known left-hemifield superiority for face processing (Gilbert and Bakan 1973), one cannot exclude the possibility that interference with faces would emerge with left-hemifield viewing of both faces and Chinese words in novices.

Finally, we note that the interpretation that a lack of dual-task inhibition implies non-overlapping of processing resources is predicated on a) there being a capacity limit to those resources, and b) utilization of those resources to that limit during our tasks. The fact that our (similar) conditions did generate interference provides some support for these assumptions. Nevertheless, some sharing of resources that falls short of those limits cannot be excluded by a lack of dual-task interference.

In conclusion, we find no evidence of dual-task inhibition between reading Chinese characters and face identity processing. This extends and parallels our previous finding using English word reading and face identity processing, and shows that the results likely apply to both alphabetic and morphosyllabic scripts.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

A post-hoc power analysis showed that the sample size used in the present study led to an estimated power (G*Power software; Faul et al. 2007, 2009) of about 0.92 in detecting a significant interference effect, based on an effect size of η2 = 0.15.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Albonico A, Barton JJS. Face perception in pure alexia: complementary contributions of the left fusiform gyrus to facial identity and facial speech processing. Cortex. 2017;96:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou M, Best CT, Tyler MD, Kroosa C. Inter-language interference in VOT production by L2-dominant bilinguals: Asymmetries in phonetic code-switching. J Phon. 2011;39:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.wocn.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton JJS, Sekunova A, Sheldon C, Johnston S, Iaria G, Scheel M. Reading words, seeing style: The neuropsychology of word, font and handwriting perception. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:3868–3877. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann M, Plaut DC. Distributed circuits, not circumscribed centers, mediate visual recognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrmann M, Plaut DC. Bilateral Hemispheric Processing of Words and Faces: Evidence from Word impairments in prosopagnosia and face impairments in pure alexia. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:1102–1118. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger DJ, Perfetti CA, Schneider W. Cross-cultural effect on the brain revisited: universal structures plus writing system variation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25:92–104. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Landis T, Regard M. Face recognition and lipreading. A Neurol Dissociation Brain. 1986;109:509–521. doi: 10.1093/brain/109.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jiang B, Gaspar C, Li C. The overlap of neural selectivity between faces and words: evidences from the N170 adaptation effect. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232:3015–3021. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-3986-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao F, Brennan C, Booth JR. The brain adapts to orthography with experience: evidence from English and Chinese. Dev Sci. 2015;18:785–798. doi: 10.1111/desc.12245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung OS, Gauthier I. Selective interference on the holistic processing of faces in working memory. J Exp Psychol Hum Perception Perform. 2010;36:448–461. doi: 10.1037/a0016471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HKS, Leung JCY, Wong VMY, Hsiao JH. When is the right hemisphere holistic and when is it not? The case of Chinese character recognition. Cognition. 2018;178:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Lehéricy S, Chochon F, Lemer C, Rivaud S, Dehaene S. Language-specific tuning of visual cortex? Functional properties of the visual word form area. Brain. 2002;125:1054–1069. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curby KM, Gauthier I. Interference between face and non-face domains of perceptual expertise: a replication and extension. Fronti Psychol. 2014;5:955. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curby KM, Moerel D. Behind the face of holistic perception: holistic processing of gestalt stimuli and faces recruit overlapping perceptual mechanisms. Atten Percept Psychophys. 2019;81:2873–2880. doi: 10.3758/s13414-019-01749-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies-Thompson J, Pancaroglu R, Barton J. Acquired prosopagnosia: structural basis and processing impairments. Front Biosci. 2014;6:159–174. doi: 10.2741/e699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feizabadi M, Albonico A, Starrfelt R, Barton JJS. Whole-object effects in visual word processing: parallels with and differences from face recognition. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2021;38:231–257. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2021.1974369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furubacke A, Albonico A, Barton JJS. Alternating dual-task interference between visual words and faces. Brain Res. 2020;1746:147004. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2020.147004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41(4):1149–1160 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gauthier I, Curran T, Curby KM, Collins D. Perceptual interference supports a non-modular account of face processing. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:428–432. doi: 10.1038/nn1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, H.V., 2014. Estimating the intrinsic dimension in fMRI space via dataset fractal analysis: Counting the ‘cpu cores’ of the human brain. arXiv. 1410.7100.

- Gerlach C, Marstrand L, Starrfelt R, Gade A. No strong evidence for lateralisation of word reading and face recognition deficits following posterior brain injury. J Cognit Psychol. 2014 doi: 10.1080/20445911.2014.928713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert C, Bakan P. Visual asymmetry in perception of faces. Neuropsychologia. 1973;11:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(73)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RJ, Rice GE, Young AW, Andrews TJ. Distinct but overlapping patterns of response to words and faces in the fusiform gyrus. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26:3161–3168. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa S, Marian V. Consequences of multilingualism for neural architecture. Behav Brain Funct. 2019;15:1–24. doi: 10.1186/s12993-019-0157-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills CS, Pancaroglu R, Duchaine B, Barton JJS. Word and text processing in acquired prosopagnosia. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:258–271. doi: 10.1002/ana.24437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao JH, Cottrell GW. Not all visual expertise is holistic, but it may be leftist: the case of Chinese character recognition. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N. Domain specificity in face perception. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:759–763. doi: 10.1038/77664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay NDS. Chinese language interference in written English. J Basic Writing. 1975;1:50–61. doi: 10.37514/JBW-J.1975.1.1.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leff AP, Spitsyna G, Plant GT, Wise RJ. Structural anatomy of pure and hemianopic alexia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:1004–1007. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.086983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Perfetti CA. The time course of brain activity in reading English and Chinese: an ERP study of Chinese bilinguals. Hum Brain Mapp. 2003;18:167–175. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Cheung AKF. Language interference in English-Chinese simultaneous interpreting with and without text. Babel. 2020;66:434–456. doi: 10.1075/babel.00168.che. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macizo P, Bajo T, Cruz Martín M. Inhibitory processes in bilingual language comprehension: evidence from Spanish-English interlexical homographs. J Mem Lang. 2010;63:232–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2010.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Gray KL, Cook R. The composite face illusion. Psychon Bull Rev. 2017;24:245–261. doi: 10.3758/s13423-016-1131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nan W, Liu Y, Zeng X, Yang W, Liang J, Lan Y, Fu S. The spatiotemporal characteristics of N170s for faces and words: A meta-analysis study. PsyCh Journal. 2022;11:5–17. doi: 10.1002/pchj.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestor A, Behrmann M, Plaut DC. The neural basis of visual word form processing: a multivariate investigation. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23:1673–1684. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG, Farell B, Moore DC. The remarkable inefficiency of word recognition. Nature. 2003;423:752–756. doi: 10.1038/nature01516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepers DW, Robbins RA. A Review and Clarification of the Terms "holistic," "configural," and "relational" in the Face Perception Literature. Front Psychol. 2012;3:559. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut DC, Behrmann M. Complementary neural representations for faces and words: a computational exploration. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2011;28:251–275. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2011.609812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Li H, Wei Y, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Zhang Q. Neural mechanisms underlying the processing of Chinese and English words in a word generation task: an event-related potential study. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:970–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reicher GM. Perceptual recognition as a function of meaningfulness of stimulus material. J Exp Psychol. 1969;81:275. doi: 10.1037/h0027768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, Shao H, He S. Interaction between conscious and unconscious information-processing of faces and words. Neurosci Bullet. 2021;37(11):1583–1594. doi: 10.1007/s12264-021-00738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Gauthier I. A meta-analysis and review of holistic face processing. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1281. doi: 10.1037/a0037004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino C, Corrow SL, Duchaine B, Barton JJS. Word and text processing in developmental prosopagnosia. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2016;33:315–328. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2016.1204281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart DE, McClelland JL. An interactive activation model of context effects in letter perception: II. The contextual enhancement effect and some tests and extensions of the model. Psychol Rev. 1982;89(1):60. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.89.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir HM, Arnardottir A, Halldorsdottir ET. Faces and words are both associated and dissociated as evidenced by visual problems in dyslexia. Sci Rep. 2021;11:23000. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02440-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starrfelt R, Klargaard SK, Petersen A, Gerlach C. Are reading and face processing related? Biorxiv: An investigation of reading in developmental prosopagnosia; 2016. p. 039065. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Unicorns do exist: a tutorial on "proving" the null hypothesis. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:756–761. doi: 10.1177/070674370304801108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susilo T, Wright V, Tree JJ, Duchaine B. Acquired prosopagnosia without word recognition deficits. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2015;32:321–339. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2015.1081882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Spinks JA, Gao JH, Liu HL, Perfetti CA, Xiong J, Stofer KA, Pu Y, Liu Y, Fox PT. Brain activation in the processing of Chinese characters and words: a functional MRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;10:16–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200005)10:1<16::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Liu H-L, Perfetti CA, Spinks JA, Fox PT, Gao J-H. The neural system underlying Chinese logograph reading. Neu-Roimage. 2001;13:836–846. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan LH, Laird AR, Li K, Fox PT. Neuroanatomical correlates of phonological processing of Chinese characters and alphabetic words: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25:83–91. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JW, Farah MJ. Parts and wholes in face recognition. Q J Exp Psychol A. 1993;46:225–245. doi: 10.1080/14640749308401045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JW, Simonyi D. The "parts and wholes" of face recognition: a review of the literature. Q J Exp Psychol (hove) 2016;69:1876–1889. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2016.1146780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry G, Wu YJ. Electrophysiological evidence for language interference in late bilinguals. NeuroReport. 2004;15:1555–1558. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000134214.57469.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tso, R.V.-y., Au, T.K.-f., Hsiao, J.H.-w., Perceptual expertise: can sensorimotor experience change holistic processing and left-side bias? Psychol Sci. 2014;25:1757–1767. doi: 10.1177/0956797614541284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MY, Kuo BC, Cheng SK. Chinese characters elicit face-like N170 inversion effects. Brain Cogn. 2011;77:419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner KS, Zilles K. The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus. Neuropsychologia. 2016;83:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DD. Processes in word recognition. Cogn Psychol. 1970;1:59–85. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(70)90005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AC-N, Bukach CM, Hsiao J, Greenspon E, Ahern E, Duan Y, Lui KFH. Holistic processing as a hallmark of perceptual expertise for nonface categories including Chinese characters. J vis. 2012;12:7–7. doi: 10.1167/12.13.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YJ, Thierry G. Chinese-English bilinguals reading English hear Chinese. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7646–7651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1602-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Jiang Y, Ma L, Yang Z, Weng X. Similar spatial patterns of neural coding of category selectivity in FFA and VWFA under different attention conditions. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AW, Hellawell D, Hay DC. Configurational information in face perception. Perception. 1987;16:747–759. doi: 10.1068/p160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Ma X, Ji L, Chen S, Cao X. Sex differences in categorical adaptation for faces and Chinese characters during early perceptual processing. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;11:656. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.