Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the safety and effectiveness of intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) treatment for de novo coronary lesion involving severely calcified vessels in a Chinese population.

METHODS

The Clinical Trial of the ShOckwave Coronary IVL System Used to Treat CalcIfied Coronary ArtEries (SOLSTICE) was a prospective, single-arm, multicentre trial. According to the inclusion criteria, patients with severely calcified lesions were enrolled in the study. IVL was used to perform calcium modification prior to stent implantation. The primary safety endpoint was freedom from major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) at 30 days. The primary effectiveness endpoint was procedural success, defined as successful stent delivery with residual stenosis < 50% by core lab assessment without in-hospital MACEs. The morphological changes of calcium modification were assessed by optical coherence tomography (OCT) before and after IVL treatment.

RESULTS

Patients (n = 20) were enrolled at three sites in China. Severe calcification by core lab assessment was present in all lesions, with a mean calcium angle and thickness of 300 ± 51° and 0.99 ± 0.12 mm (by OCT), respectively. The 30-day MACE rate was 5%. Both primary safety and effectiveness endpoints were achieved in 95% of patients. The final in-stent diameter stenosis was 13.1% ± 5.7% with no patient had a residual stenosis < 50% after stenting. No serious angiographic complications (severe dissection grade D or worse, perforation, abrupt closure, slow flow/no-reflow) observed at any time during the procedure. OCT imaging demonstrated visible multiplane calcium fracture in 80% of lesions with a mean stent expansion of 95.62% ± 13.33% at the site of maximum calcification and minimum stent area (MSA) of 5.34 ± 1.64 mm2.

CONCLUSIONS

The initial coronary IVL experience for Chinese operators resulted in high procedural success and low angiographic complications consistent with prior IVL studies, reflecting the relative ease of use of IVL technology.

The presence of coronary calcification is universal in all patients with documented coronary artery disease. The prevalence of coronary artery calcification is age and gender dependent, occurring in more than 90% of men and 67% of women older than 70 years.[1,2] At the 10-year follow-up, the presence of heavy calcification was an independent predictor of mortality, with a similar prognosis following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).[3] Angiographically severe coronary artery calcification (CAC) is detected in one-fifth of patients undergoing PCI and negatively affects outcomes[4] by hampering device crossing and stent apposition and expansion, disrupting drug-eluting polymers from stent platforms, and impairing drug delivery and elution kinetics.[5] Multiple treatment options are available to modify lesion calcification, including high-pressure noncompliant balloons, specialty balloons (scoring, cutting, ultrahigh pressure) and atherectomy. all of which have several restrictions. Balloon dilatation could change the morphology of calcified plaque and provide circumferential plaque modification, as evidenced by the findings of multiple calcium fractures in single cross sections. The benefit of rotational atherectomy (RA) can reduce plaque volume and modify plaque. But the procedure of RA is complicated and the incidence of complications is high.

Coronary shockwave intravascular lithotripsy (CS-IVL) is a balloon-based technique for lesion modification of severely calcific plaque lesions in coronary[6-9] and peripheral vessels.[10] Single-arm studies of IVL in coronary arteries, including Disrupt CAD I,[6] Disrupt CAD II,[7] Disrupt CAD III,[8] and Disrupt CAD IV,[9] reported high procedural success rates with a low risk of complications in patient populations from the USA, Europe and Japan. The purpose of the ShOckwave Coronary Intravascular Lithotripsy (IVL) System Used to Treat CalcIfied Coronary ArtEries (SOLSTICE) trial was to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the Shockwave C2 Coronary IVL Systemin in Chinese population.

METHODS

Study Design

The SOLSTICE trial was a prospective, multicentre, single-arm trial designed to assess the safety and effectiveness of the Shockwave C2 coronary IVL system to treat de novo calcified coronary lesions prior to stenting. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study procedures were in compliance with Good Clinical Practices (GCP), the Declaration of Helsinki, and all applicable national requirements in China, as well as the local Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board requirements.

Patients

The eligibility criteria for the current study were similar to those for the Disrupt CAD III and Disrupt CAD IV studies.[8,9] The inclusion criteria included subjects ≥ 18 and ≤ 80 years of age, severe calcification, total length of calcium of at least 15 mm and lesion length not exceeding 40 mm. The target vessel reference diameter had to be ≥ 2.5 mm and ≤ 4.0 mm. The subject or legally authorized representative signed a written informed consent form to participate in the study prior to any study-mandated procedures. The exclusion criteria included acute myocardial infarction, heart failure (LVEF ≤ 35%), stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) within 6 months, uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 10%), uncontrolled hypertension (systolic BP > 180 mmHg or diastolic BP > 110 mmHg), renal failure with serum creatinine > 2.5 mg/dL or chronic dialysis, pregnancy, inability to tolerate dual antiplatelet therapy for at least 6 months, haemoglobin < 10 g/dL, coagulopathy, left main lesion, tortuous and ostial lesions, saphenous vein graft lesions, and dissection worse than grade C. All patients were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 12 months. Patients with high bleeding risk, DAPT was prescribed as current guidelines for a minimum of 6 months.[11]

Study Device and Procedures

PCI was performed via femoral or radial access with a minimum 6F guiding catheter. Adjunctive approaches (e.g., buddy wire, pre-dilatation with a small diameter balloon [1.5–2.0 mm], or guide catheter extension) were used if the IVL catheter was unable to cross the lesion at the operator’s discretion before reinsertion of the IVL catheter. The study device was a single-use Shockwave C2 Coronary IVL catheter (Shockwave Medical Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA), which contains two lithotripsy emitters enclosed within an integrated balloon. The 12-mm fluid-filled balloon angioplasty IVL catheter, available in diameters ranging from 2.5 mm to 4.0 mm, was connected via a dedicated connector cable to the generator, which was programmed to deliver 10 sequential pulses at 1 pulse/s for up to 80 pulses per catheter. The IVL balloon was selected according to sized 1: 1 in relation to the reference vessel diameter, located at the target lesion and inflated to 4 atm, and 10 pulses of IVL were delivered; the balloon was then inflated to 6 atm, and this process was repeated 10-15 s later depending on whether the balloon was completely inflated. Heart rate and rhythm, blood pressure, and chest pain were monitored during the process. Subsequent stent placement was followed by high pressure (> 16 atm) postdilatation using a noncompliant balloon. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging was performed at the three point of time pre-IVL, post-IVL, and post-stent to characterize the extent of calcification and provide insights into the mechanism of IVL in facilitating stent expansion.

Endpoints

The primary safety endpoint was freedom from MACEs within 30 days of the index procedure. The effectiveness primary endpoint was procedural success defined as stent delivery with residual stenosis < 50% by core laboratory assessment and without in-hospital MACEs. MACEs were defined as cardiac death; myocardial infarction (MI) was defined as a CK-MB level > 3 times the upper limit of the lab normal (ULN) value with or without a new pathologic Q wave at discharge (periprocedural MI) according to the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction beyond discharge (spontaneous MI); and target vessel revascularization (TVR) was defined as revascularization at the target vessel (inclusive of the target lesion) after the completion of the index procedure. The secondary endpoints included the freedom from MACEs at 180 days, and freedom from arrhythmia, chest pain, blood pressure drop, perforation, slow flow, no reflow, or type D, E, or F dissection at any point during the procedure. The 30-day and 180-day follow-up results were obtained by telephone follow-up.

Data Quality

Study data were regularly reviewed for accuracy and completeness by an independent monitoring group (WuXi Clinical Development Services, Shanghai, China). Independent core laboratories analysed the angiography and OCT images (Xinyinmeiying, Beijing, China). Data management (Xinyinmeiying, Beijing, China) and data analysis (Xinyinmeiying, Beijing, China) were performed by independent organizations. Adverse events were adjudicated by an independent Clinical Events Committee (Cardiovascular Research Foundation). An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board reviewed the safety data on a regular basis and monitored the validity and scientific merit of the study.

Statistical Analysis

All summaries were based on subjects or lesions with evaluable data. No imputation was performed for missing data. Continuous variables are described as the means ± SD; dichotomous and categorical variables are described as counts and proportions. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), version 9.4. Statistical comparisons of OCT data were performed by Student’s t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients and Procedures

Baseline and angiographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Between July 2021 and November 2021, 20 patients were enrolled at 3 hospitals in China. The patients included 16 (80%) male, 14 (70%) hypertension,9 (45%) hyperlipidaemia, 10 (50%) diabetes mellitus, 5 (25%) smokers, and without renal insufficiency patients, the average age was 65.2 ± 8.1 years. All patients successfully performed coronary angiography and results showed the coronary stenosis with severe calcification. The target vessels included 16 (80.0%) left anterior descending arteries, 1 (5%) left circumflex branch and 3 (15%) right coronary arteries. The quantitative coronary angiography analysis was performed by angiographic core laboratory. The mean reference vessel diameter (RVD) was 2.80 ± 0.3 mm. The mean minimum lumen diameter was 0.79 ± 0.38 mm, with a corresponding percent diameter stenosis on quantitative coronary angiography of 72.7% ± 12.0%. The mean calcified length was 46.0 ± 9.66 mm, and the mean lesion length was 27.6 ± 7.4 mm.

Table 1. Baseline and angiographic characteristics.

| Age, yrs | 65.2 ± 8.1 |

| Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%) unless other indicated. N = 20. LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx: left circumflex coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery. | |

| Male | 16 (80%) |

| Hypertension | 14 (70%) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 9 (45%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (50%) |

| Current smoker | 5 (25%) |

| Renal insufficiency | 0 |

| Target vessel | |

| LAD | 16 (80%) |

| LCx | 1 (5%) |

| RCA | 3 (15%) |

| Average reference vessel diameter, mm | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

| Minimum lumen diameter, mm | 0.79 ± 0.38 |

| Diameter stenosis | 72.7% ± 12.0% |

| Lesion length, mm | 27.6 ± 7.4 |

| Calcified length, mm | 46.0 ± 9.66 |

| Severe calcification | 100% |

Procedures and Outcomes of IVL Treatment

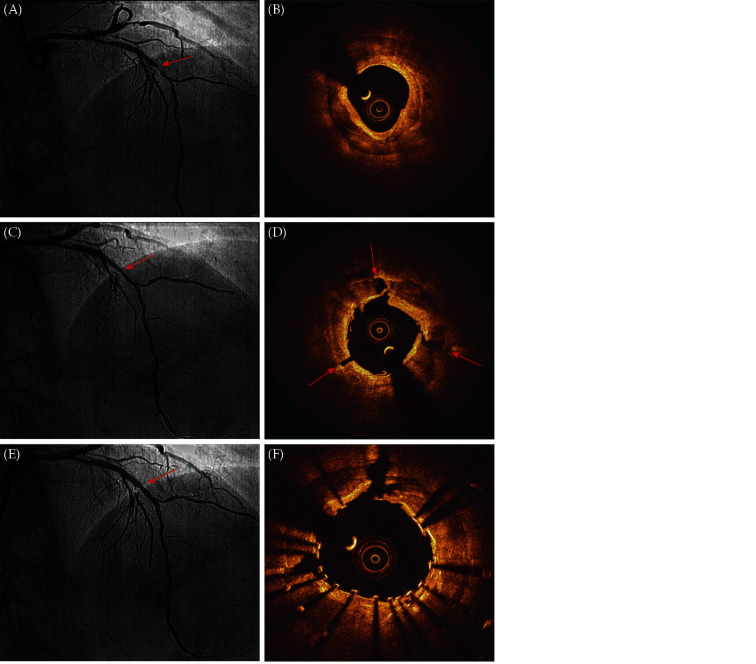

Procedural details are provided in Table 2. IVL balloon directly reached the target lesion in 7 (35%) of the patients. Pre-dilatation to deliver the IVL balloon catheters across the lesion was required in 13(65%) of cases, atherectomy was not required in any cases. An average number of 1.1 ± 0.3 IVL catheter was used in per lesion, the ratio of the number of pulses to lesion length was 1: 2.2 in this trail. All cases were successfully implanted drug-eluting stents (DESs) after IVL balloon pre-treatment, the residual stenosis at the target lesion was less than 2% after stent implantation, the mean number of stents were 1.3 ± 0.5. The example of IVL treatment was shown in Figure 1. The IVL balloon morphology changes were observed by X-ray fluoroscopy during the treatment, ECG monitoring and blood pressure were also observed. The average number of pulses per case was 61.5 ± 28.1, coronary angiograph showed that the acute luminal gain was 0.83 ± 0.37 mm and the residual stenosis was 13.1 ± 5.7% after IVL treatment, with no patient had a residual stenosis < 50% after stenting. There were no coronary perforation, slow flow or no reflow, severe dissection (grade C or worse) during the procedure (Table 3). Coronary blood flow was TIMI 3 in all patients. Ventricular fusion wave was observed in all patients during the IVL procedure and disappeared after treatment. There was no other arrhythmia and ischemic changes in ECG monitoring.

Table 2. Procedural characteristics.

| Data are presented as mean ± SD unless other indicated. IVL: intravascular lithotripsy. | |

| Pre-IVL dilatation | 65% |

| Number of IVL catheters | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| IVL pulses | 61.5 ± 28.1 |

| Max IVL inflation pressure, atm | 6.0 |

| Post-IVL dilatation | 50% |

| Number of stents | 1.3 ± 0.5 |

| Succeeded stent delivery | 100% |

| Post-stent dilatation | 100% |

Figure 1.

The procedure of IVL treatment and OCT cross-sectional image.

(A): Coronary angiography showed a stenotic lesion with severely calcification in the mid-LAD (red arrow); (B): OCT examination showed severe calcification in the mid-LAD, calcification arc was 360°, maximum calcification thickness was 1.21 mm, calcification score was 4 points, the minimum lumen area was 2.82 mm2; (C): after IVL balloon (3.0 × 12 mm) treatment, the stenosis in the mid-LAD was reduced, with A-type dissection (red arrow); (D): fracture of multiple calcified rings at 12 o'clock, 4 o'clock and 8 o'clock (red arrow) after IVL treatment, lumen area increased significantly. maximum depth of calcium fractures was 0.85 mm (4 o'clock, red arrow); (E): coronary angiography after stenting; and (F): good stent expansion and apposition, and the minimum lumen was 5.57 mm2. IVL: intravascular lithotripsy; LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery.

Table 3. Angiographic complications.

| Complications | Immediately post-IVL | Final poststent |

| IVL: intravascular lithotripsy. | ||

| Any serious angiographic complication | 0 | 0 |

| Severe dissection (grade CD or worse) | 0 | 0 |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 |

| Abrupt occlusion | 0 | 0 |

| Slow flow | 0 | 0 |

| No reflow | 0 | 0 |

All patients completed clinical follow-up, MACE was judged by the Clinical Events Committee. One patient was diagnosed as acute myocardial infarction without any symptoms or ECG abnormalities after coronary intervention, the 30-day MACE rate was 5%. There were no newly occurred MACEs during the 180-day follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4. Primary endpoint and follow-up.

| N = 20. *Procedure success: stent delivery with residual stenosis < 50% without in-hospital MACEs; **MACEs: cardiac death, MI, TVR; MI: CK-MB level > 3 × ULN at discharge (periprocedural MI) and using the 4th Universal Definition of MI beyond discharge; ***One patient with CK-MB > 3 × ULN after index procedure without symptom or ECG abnormality. MACE: major adverse cardiac events; MI: myocardial infarction; TVR: target vessel revascularization; ULN: upper limit of the lab normal. | |

| Effectiveness endpoint: procedure success* | 95%*** |

| Safety endpoint: freedom from 30-day MACE** | 95%*** |

| Freedom from 180-day MACE** | 95%*** |

OCT Analysis

OCT was performed at three sites of before IVL, post-IVL and after stenting in all patients. The results of OCT analysis were shown in Table 5. At the site of maximum calcification, the mean calcium thickness was 0.99 ± 0.12 mm, and calcium angle was 300.41° ± 51.19°. The OCT calcification score was 4 points in all patients. The minimal luminal area from 1.41 ± 0.59 mm2 and maximum area stenosis was 77.46% ± 6.68%. After IVL treatment, the lumen area was significantly increased (1.41 ± 0.59 mm2 vs. 3.10 ± 0.69 mm2, P < 0.001). The fracture of calcified rings was seen in each lesion (Figure 1). After DES implantation and post dilation, the in-stent lumen area was 5.34 ± 1.64 mm2, and the final stent expansion was 95.62% ± 13.33%.

Table 5. OCT results.

| Pre-IVL | Post-IVL | Final in-stent | |

| Data are presented as mean ± SD. OCT: optical coherence tomography; IVL: intravascular lithotripsy. | |||

| Minimum lumen area, mm2 | 1.41 ± 0.59 | 3.10 ± 0.69 | 5.54 ± 1.62 |

| Maximum area stenosis, % | 77.46% ± 6.68% | 50.97% ± 11.25% | 17.61% ± 6.22% |

| Maximum calcium angle | 300.41° ± 51.19° | - | - |

| Maximum calcium thickness, mm | 0.99 ± 0.12 | - | - |

| Stent expansion | - | - | 95.62% ± 13.33% |

| Minimum stent area, mm2 | - | - | 5.34 ± 1.64 |

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of IVL for the modification of severely calcified coronary artery lesions in a Chinese population. The major findings are as follows: (1) IVL was a safe and efficacious tool for CAC plaque modification, with trafficability in all cases. All stents easily passed through the target lesions after IVL treatment and obtained a good expansion effect. (2) IVL was safe, without reported dissections, perforations, abrupt closure, or slow flow/no reflow, only 1 (5%) patient occurred 30-day and 180-day MACEs without clinical symptoms in this severely calcified lesion group. The benefit of IVL is that it preferentially allows for calcium modification without affecting the endovascular soft tissue. Current techniques to modify calcific plaques can cause coronary artery wall injury, which can lead to vascular restenosis. Furthermore, perforation rates reported in the literature have ranged from approximately 1.7% with RA[12] and 0.9% with orbital atherectomy (OA),[13] whereas no perforations have been observed with IVL[14] in previous studies or our studies. There are some reported complications with IVL for peripheral use such as balloon rupture (15%)[15] and balloon shaft breakage, however severely complications reported for coronary artery use was rare.[8,9] These complications did not occur in our trail because we strictly followed the protocol during the whole procedure. Tortuous lesions and heavy calcified cap lesions were not contraindication of IVL. IVL provides circumferential plaque modification, as certified by the results of multiple calcium fractures recorded by OCT in single cross sections. It does not rely on mechanical tissue injury due to physical interaction, but rather by a diffuse acoustic pulse through a balloon inflated at low pressure of 4 to 6 atm. These two advantages have the potential advantage of uniform energy distribution and thus uniform plaque modification, resulting in enhanced stent apposition and expansion.[14]

Moreover, shockwaves are more advantageous when addressing deep calcifications. Shockwave pulses affect calcium sheets regardless of their depth in the vessel wall. RA or OA is less effective in modifying deep-seated calcium.[16,17] Last, in contrast to plaque abrasion by RA or OA, which generates microparticles that embolize distally, thus impairing microcirculatory function, large calcium fragments generated by lithoplasty remain in situ. Indeed, compared with the incidences of 0 to 2% in contemporary series with RA, there were no incidents of slow flow/no-reflow observed with lithoplasty in the DISRUPT CAD I study.

The successful use of IVL in coronaries for ISR has been associated with stents under expansion due to fibrocalcific disease, as well as the use of IVL peripherally to facilitate transfemoral access for large-bore catheter procedures (TAVR, EVAR, TEVAR, Impella/MCS).[18-20] These new applications could provide greater application possibilities for IVL.

Given the reassuring results of the Disrupt CAD program, followed by several large real-world multicentre registries[21,22] and paired with the ease of use of this technology, it is expected that CS-IVL will be rapidly adopted and considered by many as the preferred first line of balloon-based therapy to manage severely calcified lesions before DES implantation. The potential off-label use of this device in restenotic lesions, in which long-term stent underexpansion due to a calcified lesion is frequent, is also intuitively appealing.[23]

After a rough comparison of the results of the SOLSTICE trial with the CADIII and CAD IV studies, we found that SOLSTICE trial patients were much younger (71.2 ± 8.6 years in CAD III, 75.0 ± 8.0 years in CAD IV, 65.2 ± 8.1 in SOLSTICE), the minimum lumen area at baseline was smaller (1.1 ± 0.4 mm in CAD III, 1.00 ± 0.34 mm in CAD IV, 0.79 ± 0.38 mm in SOLSTICE), and the angle of the calcified lesion was larger (292.5 ± 76.5° in CAD III, 257.9 ± 78.4° in CAD IV, 300.41 ± 51.19° in SOLSTICE), suggesting that the lesions were more calcified in SOLSTICE. More post-IVL dilatations were used (20.7% in CAD III, 1.6% in CAD IV, 50% in SOLSTICE), and larger acute gains (1.68 ± 0.46 mm in CAD III, 1.67 ± 0.37 mm in CAD IV, 1.86 ± 0.37 mm in SOLSTICE) were achieved in the SOLSTICE trial. The large proportion of post-IVL dilatation use might have been related to the habits of Chinese physicians. The results are provided in Supplementary Tables 2 to 6.

We recommend a ratio of lesion length to number of IVL pulses of 2 for treatment using IVL. The ratios of lesion length to number of IVL pulses in CAD II, CAD III, and CAD IV were 3.6, 2.6 and 3.7, respectively. The ratio of the SOLSTICE trial (2.2) was the smallest of all studies, and OCT analysis showed that the proportion of fractures of target lesions was the greater in the SOLSTICE trial (more than 3 fractures per lesion for 30%), while the SOLSTICE trial had no complications. The ratio of lesion length to number of IVL pulses of 2 might not only meet the requirements for Calcific Plaque Modification but might also reduce the occurrence of complications. The results must be verified by further clinical studies. The 30-day MACE rate was 5%, and no additional MACEs occurred during the 180-day follow-up. There was one patient with CK-MB > 3 x ULN after the index procedure without any symptoms or ECG abnormalities during this time period. The microthrombus could have played a role in this patient.

In conclusion, the SOLSTICE trial demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of IVL to facilitate stent delivery and optimize stent expansion in a Chinese population. The initial coronary IVL experience for Chinese interventional doctors resulted in high procedural success and low angiographic complications consistent with prior IVL studies, reflecting the relative ease of use of IVL technology. The optimal therapy for calcified coronary artery disease is multiadjunctive, and several strategies should be available in the cardiac catheterization clinic, where selection depends on the nature of the calcific plaque and its anatomical distribution.[24]

This study had a number of limitations. Most importantly, the present study was nonrandomized and lacked a concurrent control group. It will cause bias in case selection. Second, the sample size of our trail was small, the sampling error increased. Observation of interventional therapy related complications and MACEs required a lager sample size. Therefore, a lager sample size and selecting various types of calcified lesions clinical studies should be carried out later.

References

- 1.Wong ND, Kouwabunpat D, Vo AN, et al Coronary calcium and atherosclerosis by ultrafast computed tomography in asymptomatic men and women: relation to age and risk factors. Am Heart J. 1994;127:422–430. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goel M, Wong ND, Eisenberg H, et al Risk factor correlates of coronary calcium as evaluated by ultrafast computed tomography. Am Journal Cardiology. 1992;70:977–980. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90346-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawashima H, Serruys PW, Hara H, et al 10-year all-cause mortality following percutaneous or surgical revascularization in patients with heavy calcification. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourantas CV, Zhang YJ, Garg S, et al Prognostic implications of coronary calcification in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease treated by percutaneous coronary intervention: a patient-level pooled analysis of 7 contemporary stent trials. Heart. 2014;100:1158–1164. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kereiakes DJ, Virmani R, Hokama JY, et al Principles of intravascular lithotripsy for calcific plaque modification. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1275–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinton TJ, Ali ZA, Hill JM, et al Feasibility of shockwave coronary intravascular lithotripsy for the treatment of calcified coronary stenoses. Circulation. 2019;139:834–836. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali ZA, Nef H, Escaned J, et al Safety and effectiveness of coronary intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of severely calcified coronary stenoses: the disrupt CAD II study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e008434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.119.008434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill JM, Kereiakes DJ, Shlofmitz RA, et al Intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of severely calcified coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2635–2646. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito S, Yamazaki S, Takahashi A, et al Intravascular lithotripsy for vessel preparation in severely calcified coronary arteries prior to stent placement- primary outcomes from the Japanese disrupt CAD IV study. Circ J. 2021;85:826–833. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassimis G, Didagelos M, De Maria GL, et al Shockwave intravascular lithotripsy for the treatment of severe vascular calcification. Angiology. 2020;71:677–688. doi: 10.1177/0003319720932455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The Task Force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213–260. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdel-Wahab M, Richardt G, Joachim Buttner H, et al High-speed rotational atherectomy before paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation in complex calcified coronary lesions: the randomized ROTAXUS (Rotational Atherectomy Prior to Taxus Stent Treatment for Complex Native Coronary Artery Disease) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers JW, Feldman RL, Himmelstein SI, et al Pivotal trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the orbital atherectomy system in treating de novo, severely calcified coronary lesions (ORBIT II) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.01.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Silva K, Roy J, Webb I, et al. A calcific, undilatable stenosis: lithoplasty, a new tool in the box? JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 10: 304-306.

- 15.Chugh Y, Khatri JJ, Shishehbor MH, et al Adverse events with intravascular lithotripsy after peripheral and off-label coronary use: a report from the FDA MAUDE database. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33:E974–E977. doi: 10.25270/jic/21.00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serruys PW, Katagiri Y, Onuma Y. Shaking and breaking calcified plaque: lithoplasty, a breakthrough in interventional armamentarium? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 10: 907-911.

- 17.Kini AS, Vengrenyuk Y, Pena J, et al Optical coherence tomography assessment of the mechanistic effects of rotational and orbital atherectomy in severely calcified coronary lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:1024–1032. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomey MI, Sharma SK Interventional options for coronary artery calcification. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2016;18:12. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tovar Forero MN, Wilschut J, Van Mieghem NM, et al Coronary lithoplasty: a novel treatment for stent underexpansion. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:221. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Mario C, Chiriatti N, Stolcova M, et al Lithoplasty-assisted transfemoral aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J. 2018;41:942. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Jattari H HW, De Roeck F, Cottens D, et al intracoronary lithotripsy in calcified coronary lesions: a multicenter observational study. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E24–E31. doi: 10.25270/jic/21.00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aziz A, Bhatia G, Pitt M, et al Intravascular lithotripsy in calcified-coronary lesions: A real-world observational, European multicenter study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:225–235. doi: 10.1002/ccd.29263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassimis G, Didagelos M, Kouparanis A, et al Intravascular ultrasound-guided coronary intravascular lithotripsy in the treatment of a severely under-expanded stent due to heavy underlying calcification. To re-stent or not? Kardiol Pol. 2020;78:346–347. doi: 10.33963/KP.15173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Maria GL, Scarsini R, Banning AP. Management of calcific coronary artery lesions: is it time to change our interventional therapeutic approach? JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019; 12: 1465-1478.