Abstract

In this work, 1-(4-bromophenyl)-2a,8a-dihydrocyclobuta[b]naphthalene-3,8‑dione (1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D) has been characterized by single crystal X-ray to get it's crystal structure with R(all data) - R1 = 0.0569, wR2 = 0.0824, 13C and 1HNMR, as well as UV–Vis and IR spectroscopy. Quantum chemical calculations via DFT were used to predict the compound structural, electronic, and vibrational properties. The molecular geometry of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-Dwas optimized utilizing the B3LYP functional at the 6–311++G(d,p) level of theory. The Infrared spectrum has been recorded in the range of 4000–550 cm−1. The Potential Energy Distribution (PED) assignments of the vibrational modes were used to determine the geometrical dimensions, energies, and wavenumbers, and to assign basic vibrations. The UV–Vis spectra of the titled compound were recorded in the range of 200-800 nm in ACN and DMSO solvents. Additionally, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gap and electronic transitions were determined using TD-DFT calculations, which also simulate the UV–Vis absorption spectrum. Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis can be used to investigate electronic interactions and transfer reactions between donor and acceptor molecules. Temperature-dependent thermodynamic properties were also calculated. To identify the interactions in the crystal structure, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis was also assessed. The Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) and Fukui functions were used to determine the nucleophilic and electrophilic sites. Additionally, the biological activities of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D were done using molecular docking. These results demonstrate a significant therapeutic potential for 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D in the management of Covid-19 disorders. Molecular Dynamics Simulation was used to look at the stability of biomolecules.

Keywords: DFT, Hirshfeld analysis, Molecular docking, Molecular docking simulation, FT-IR

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Quinones are one of the most explored classes of naturally occurring bioactive molecules isolated from plants and microorganisms playing key pharmacological roles in cancer and inflammation [1]. Moreover, they have also been found effective in managing hepatitis B, cardiovascular, and reproductive disorders [2]. Quinones are 2e− and 2H+ acceptors and participate in cellular redox and alkylation reactions to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) by exhibiting molecular interactions with mitochondrial oxidoreductases such as ubiquinone reductase (NQO1), cytochrome P450 (CYP450), and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) [3]. However, their potential use in the management of SARS-CoV-2 has garnered considerable interest recently as the quinone-based scaffolds, such as vitamin K, coenzyme Q10, dexamethasones, and methylprednisolone, have proven effective in managing the progression and increasing the survival rate of the SARS-CoV-19 patients [4]. They are believed to target CYS-145, a common protein in the main protease (Mpro) and 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) present in the COVID-19 virus [5].

Nevertheless, despite constant developments for the effective control of SARS-CoV-19, the emergence of different resistant variants remains a significant hurdle worldwide. Therefore, the primary step towards antiviral drug designing processes for acquiring a lead candidate is to understand a target molecule's structural and electronic features. In this regard, we were intrigued to explore the scope of a naphthoquinone-based scaffold synthesized by our group as a potential lead for the SARS-CoV-19 management, as naphthoquinones exhibit unique biological properties attributed to the electronic properties that are brought through their structural characteristics and also earn them less toxicity, optimum solubility, and effective target binding [6]. The effectiveness of naphthoquinone warrants investigation also because they bear an uncanny resemblance to quinone-containing drugs. Their computational studies have deciphered the mechanistic understanding of the inhibitory function of quinones in preventing SARS-CoV-2. Thus, we initiated our investigation to perform the crystallographic, DFT and docking studies of the naphthoquinone derivative to reveal its structural correlation with the SARS-Co-19 proteases. The study also aims to provide a basic understanding of the electronic features that could support designing ideal lead molecules for the management of SARS-CoV-19.

2. Computational details

The molecular geometry was not restricted, and all the calculations (like structural optimization, vibrational analysis, and several other properties of a molecule) were performed by using Gauss View molecular visualization program [7] and Gaussian 09 program package on a computing system [8]. Additionally, the calculated vibrational frequencies were processed by means of Potential Energy Distribution (PED) analysis of all the fundamental vibration modes by using the VEDA4 program [9]. Crystal Explorer version 17.5 software [10] was used to plot Hirshfeld surfaces mapped using dnorm and their corresponding 2D fingerprint plots described in this work in order to examine the interactions in the crystal [10]. Also, the structure electronic transitions and analyses were investigated utilizing TD-DFT and DFT/gage-including atomic orbitals (GIAO) methods, as well as UV–Vis, 1H, and 13C NMR spectroscopy techniques. Moreover, the information regarding the reactivity of the studied compound was gathered by using their MEP and the HOMO-LUMO transitions. A study of natural bond orbital was performed using the NBO program [11]. In order to examine the molecule reactive behavior, Fukui functions were also supplied. At different temperatures, thermodynamical properties were carried out via the ORCA 4.0.1 software [12]. The Multiwfn and Origin 8.0 software was used to construct each graph, including the computed IR and UV–Vis graphs [13]. Molecular docking was completed effectively using Autodock-Vina and Chimera [14].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Crystal structure and geometrical parameters

According to an X-ray diffraction study, the compound under examination crystallizes with a single independent molecule in the asymmetric unit ( Fig. 4 (A)). According to the information in Table 2, the title compound has two molecules per unit cell (Z = 2) and belongs to the triclinic crystal system with space group P-1. At 296(2)K, the unit cell dimensions are as follows: a = 7.3248(9) Å; b = 8.3911(11) Å; c = 11.8804(15) Å; α = 88.783(6)°, β = 73.041(7)° and γ = 76.474(6)°; and V = 678.21(15) Å3. The full-matrix least-squares approach on F2 was refined, and the resulting goodness of fit was 1.018. Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] are R1 = 0.0351, wR2 = 0.0760, while R indices (all data) are R1 = 0.0569, wR2 = 0.0824. Selected intermolecular interactions are listed in Table 3. The major supramolecular interaction in the compound is observed from the active bromine attached to the aromatic ring. It undergoes halogen bonding interaction with the carbonyl oxygen of the other molecule leading to the formation of a linear chain. The C—H …O type interaction observed between the hydrogen attached to the aromatic ring and the oxygen atom of another carbonyl extends the supra aggregation behavior to the two dimensions. The Pi…Pi stacking interaction and C—H..C type interaction between the hydrogen of the four-membered ring and aromatic phenyl rings further extend the aggregation to three dimensions. The three-dimensional packing diagram developed by these prevalent supramolecular forces is shown in Fig. 5, with their selected geometrical parameters summarized in Table 3. The experimental bond lengths and angles are all within the expected ranges. Table ST1 lists the observed and theoretical structural characteristics of the investigated compound. We carefully compare the optimized parameters to those obtained using the single crystal X-ray diffraction method and find that the bond lengths and bond angles are comparable. The calculating approach, which used separated molecules in the gaseous state for theoretical values and solid state for experimental values, can be attributed to the discrepancy between experimental and theoretical values. Bond lengths and bond angles, as demonstrated, are quite close to the observed values ( Fig. 4 (B)). The bond length Br(1)-C(2) and C18 - O22 are found to be 1.909 Å and 1.221 Å (calculated) and somewhat different from the observed value (1.895(2)Å and 1.214(3)Å). According to Table ST1, the estimated bond length of C(20)-O(24) is determined to be 1.222 Å, which is in good agreement with the observed value of 1.207 Å.

Fig. 4.

(A) ORTEP and (B) Optimized structure of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

Table 2.

Crystal data and structure refinement for 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

| Crystal data | |

|---|---|

| CCDC No. | 1,917,679 |

| Empirical formula | C18H11BrO2 |

| Formula weight | 339.18 |

| Temperature/K | 296(2) K |

| Crystal system | Triclinic |

| Space group | P −1 |

| a/Å | 7.3248(9) |

| b/Å | 8.3911(11) |

| c/Å | 11.8804(15) |

| α/° | 88.783(6)°. |

| β/° | 73.041(7)° |

| γ/° | 76.474(6)° |

| Volume/Å3 | 678.21(15) |

| Z | 2 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 | 1.661 |

| μ/mm-1 | 3.031 mm-1 |

| F(000) | 340 |

| Crystal size/mm3 | 0.155 × 0.095 × 0.035 |

| Radiation | Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073) |

| 2Θ range for data collection/° | 1.794 to 27.679° |

| Index ranges | −9<=h<=9, −10<=k<=10, −15<=l<=15 |

| Reflections collected | 11,142 |

| Independent reflections | 3141 [R(int) = 0.0383] |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 3141/0/190 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.018 |

| Final R indexes [I>=2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0351, wR2 = 0.0760 |

| Final R indexes [all data] | R1 = 0.0569, wR2 = 0.0824 |

| Largest diff. peak/hole / e Å−3 | 0.419 and −0.466 e.Å-3 |

Table 3.

Geometrical Parameters of Intermolecular Interactions involved in compound packing.

| D—G …….A | d(D—G) | d(G….A) | d(D…A) | < (DGA) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C(1)—Br(1)…..O(1)#1 | 1.895(3) | 3.205(2) | 5.001 | 156.64(9) | Aromatic C—Br..O |

| C(3)—H(3)…..O(2)#1 | 0.930 | 2.425(3) | 3.279 | 152.65(7) | Aromatic C—H..O |

| C(10)—H(10)…..C(2) | 0.980 | 2.828(7) | 3.676 | 145.32 | Cyclo butane C—H…π Phenyl |

| C(11)…..C(16) | 3.382 | π…. π stacking | |||

| C(12)……C(17) | 3.398 | π…. π stacking |

Note: Symmetry transformations used to generate equivalent atoms:x,y,z,2-x,1-y,1-z;1-x,1-y,-z,-x,1-y,-z;-x,1-y,-z,−2 + x,1 + y,z;x,y,z,1-x,1-y,-z;x,y,z,1-x,1-y,-z.

Fig. 5.

The selected non-covalent interactions of the compound with their measurements.

3.2. Vibrational analysis

We have used infrared spectroscopy to conduct a vibrational study to learn more about the crystal structure. Molecular groups can be identified and tiny details about their conformations can be discovered using IR spectroscopy. The method for locating the actual binding sites is crucial. A spectral resolution in the range of 4000–550 cm−1 was used to record the IR absorption spectrum. Fig. 6(A and B, respectively) compares the theoretical and experimental IR spectrum. Table 4 shows some of the main IR intensities whereas, Table ST2 displays other IR intensities, estimated and experimental frequencies (scaled and unscaled), as well as vibrational assignments for the gaseous phase of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D as determined by the VEDA program (based on the percentage total energy). The titled molecule consists of 32 atoms and 90 normal vibration modes, assuming the C1 symmetry group. Below are discussions for the most significant locations that only cover a few groups.

Fig. 6.

(A) Theoretical and (B) Experimental FT-IR spectra of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

Table 4.

Calculated vibrational frequencies (cm−1) assignments of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D based on B3LYP/6311++G(d.p)basis set.

| Mode No | Experimental wave number (cm-1) | Theoretical wave number (cm-1) |

IIR | Assignments (PED) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR | Unscaled | Scaled | |||

| 37 | – | 3204 | 3080 | 1 | γ CH(71) |

| 36 | – | 3203 | 3078 | 3 | γ CH(74) |

| 35 | – | 3202 | 3078 | 1 | γ CH(65) |

| 34 | – | 3201 | 3076 | 1 | γ CH(46) |

| 33 | – | 3197 | 3072 | 3 | γ CH(49) |

| 32 | 3065 | 3188 | 3064 | 1 | γ CH(47) |

| 31 | – | 3186 | 3062 | 3 | γ CH(82) |

| 30 | – | 3175 | 3051 | 2 | γ CH(42) |

| 29 | – | 3172 | 3048 | 1 | γ CH(93) |

| 28 | – | 3068 | 2949 | 4 | γ CH(79) |

| 27 | 2932 | 3058 | 2939 | 4 | γ CH(79) |

| 26 | 1679 | 1741 | 1673 | 100 | γ OC(62) |

| 25 | – | 1733 | 1665 | 29 | γ OC(64) |

| 24 | 1583 | 1660 | 1595 | 2 | γ CC(23) |

| 23 | – | 1628 | 1564 | 19 | γ CC(36) |

| 22 | – | 1626 | 1563 | 7 | γ CC(27) |

| 21 | – | 1608 | 1545 | 1 | γ CC(25) |

| 20 | – | 1594 | 1532 | 1 | γ CC(16) |

| 19 | – | 1477 | 1419 | 1 | γ CC(21) |

| 18 | 1399 | 1428 | 1372 | 4 | γ CC(15) |

| 17 | – | 1353 | 1300 | 1 | γ CC(30) |

| 16 | – | 1324 | 1272 | 1 | γ CC(13) |

| 15 | – | 1314 | 1263 | 4 | γ CC(31) |

| 14 | – | 1311 | 1260 | 17 | γ CC(14) |

| 13 | – | 1296 | 1245 | 10 | γ CC(16) |

| 12 | 1233 | 1285 | 1235 | 43 | γ CC(17) |

| 11 | – | 1257 | 1208 | 43 | γ CC(25) |

| 10 | – | 1247 | 1199 | 2 | γ CC(10) |

| 9 | – | 1210 | 1163 | 1 | γ CC(13) |

| 8 | 1066 | 1112 | 1069 | 5 | γ CC(28) |

| 7 | – | 1084 | 1041 | 11 | γ CC(18) + γ BrC(12) |

| 6 | – | 1077 | 1035 | 2 | γ CC(25) |

| 5 | 1008 | 1055 | 1014 | 1 | γ CC(26) |

| 4 | – | 1016 | 976 | 4 | γ CC(25) |

| 3 | – | 529 | 508 | 5 | γ CC(11) |

| 2 | – | 468 | 450 | 1 | γ CC(10) |

| 1 | – | 391 | 376 | 1 | γ CC(11) + γ BrC(18) |

3.3. C—H and c-o vibrations

The typical ranges for the aromatic C—H stretching vibrations are 3100–3000 cm−1 for asymmetric stretching modes and 2990–2900 cm−1 for symmetric stretching modes [21]. The bands in this region are not significantly impacted by the positions of the substituents due to their nature. The computed C—H stretching vibrations in this study are 3080, 3078, 3076, 3072, 3064, 3062, 3051, 3048, 2949, and 2939 cm−1. PED values are expected to display higher levels between 42–93%. It is projected that a significant absorption band for C—O stretching vibrations is present between 1850 and 1550 cm-1 [22]. The C = O stretching vibrations are responsible for the strong bands seen at 1679 cm−1 in FT-IR, and the corresponding estimated wavenumbers are 1673 and 1665 cm−1 by the B3LYP technique with PED% contributions of 62% and 64%, respectively.

3.4. C—C and C-Br vibrations

The C—C stretching vibrations are essential to the structure of the aromatic ring and have a big impact on the spectrum of aromatic compounds. Carbon vibrations are attributed to the bands in the range of 1650-1400 cm-1 [23], whereas, ring stretching vibrations (C = C) are predicted to occur in the range of 1300-1000 cm-1 [24]. In this work, the FT-IR bands were observed at 2920, 1680, and 772 cm-1 . The computed values of the C—C stretching frequencies in the current study are 1595, 1564, 1563, 1545, 1532, and 1300 cm−1 for pure modes. The bands at 1444, 1035, 976, 909, 726, 675, 656, 617, 355, and 264 cm−1 are attributed to the C—C-C bending modes. The C—C-C bending mode is a mixed mode, as is shown from PED. Due to the stretching vibrations of C-Br, the bromine compounds absorb strongly in the range of 650–485 cm−1. The range of the in-plane bending vibration was 325–140 cm−1 [25]. Due to the presence of heavy atoms, a mixture of vibrations is possible, making the vibration associated with the link between the ring and the bromine atom stand out. In this study, C-Br stretching vibrations are assigned to the FT-IR spectrum band computed at wavenumbers 1041 and 376 cm−1.

3.5. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP)

Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) provides details on a molecule's relative polarity and attempts to explicate hydrogen bonding, reactivity, polarizability, and the relationship between structure and activity for specific biomolecules and medications [26]. The molecular, cellular, and organismal levels must also be understood [27]. Gauss View 5.0 software was used in Molecular Electrostatic Potential to calculate the reactivity sites for electrophiles and nucleophiles at the B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p). The mechanism of chemically active sites and the relative reactivity of atoms are depicted visually in Fig. 7. The portions of a molecule that are initially drawn to an electrophilic or nucleophilic approach are shown by an indication, and the reactants closest relative alignment has been calculated. The Potential grows as the colors change from red to blue. The positive areas (blue color) are located on hydrogen atoms, which were affiliated with nucleophilic reactivity (strongest attraction), while the negative areas (red to yellow) are located on oxygen atoms, which were related to electrophilic reactivity (strongest repulsion). These maps have a color code that falls between −4.426a.u (red) and +4.426a.u (green) (deepest blue). This link between structure and activity enables 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D to have biological effects.

Fig. 7.

Molecular electrostatic potential of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

3.6. Donor - Acceptor Interactions

The study of both intra- and intermolecular interactions may benefit from the information provided by Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis describing interactions in both filled and virtual orbital regions. The second-order Fock matrix theory in Natural Bond Orbital analysis is used to simulate the interactions between the donors and acceptors. As a result of the interaction, the localized natural bond orbital of the occupied Lewis structure (bond or lone pair) loses its occupancy and changes into a vacant non-Lewis structure (Anti-bond or Rydberg), which stabilizes the donor-acceptor interactions [28]. The larger E(2) value acquire from Eq. (1) indicates that donors have a stronger propensity to contribute and the system has a stronger conjugation effect [29].

| (1) |

Where qi, is the donor orbital occupancy, Ei and Ej are the diagonal elements, and F(i,j) is the off-diagonal NBO Fock matrix elements [30]. The results of the NBO analysis on the 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D at the DFT/B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) were interpreted in Table ST3. It is observed π (C2-C4) → π*(C3-C6) and π*(C7-C10), π(C3-C6) → π*(C2-C4) and π*(C7-C10), π(C7-C10) → π*(C2-C4), π*(C3-C6) and π*(C12-C13) which are 18.79, 17.53, 20.12, 17.66, 21.75, 19.94 and 16.93 kJ/mol respectively, remaining transitions with high E(2) are lone pair to π* as LP(2) of O22 → π*(C14-C18), (C18-C21), LP(2) of O24 → π* (C16-C20) and (C20-C23) with energy values 16.89, 19.38, 19.26 and 19.10 kJ/mol. The donor LP(2) of O22→π*(C18-C21) acceptor connections, with stabilizing energy of delocalization of 19.38 kcal/mol, has the largest stabilizing energy. The title compound percentage changes are displayed in Table ST4. The Br1 bond hybrid of the Br1-C2 bond rises 13.58% in the s character and 86.04% in the p character, as shown in Table ST4 (with hybrid orbital sp6.34). As a result, the overlapping of sp3.60 hybrid of C2 hybrid forms the connection between σBr1-C2. Br is thought to be more electronegative because Br1 (0.7115) has a greater polarization coefficient than carbon (0.7027). This can be said in the following way:

3.7. Mulliken atomic charges

The calculation of reactive atomic charges plays a crucial role in the application of quantum mechanical calculations for the molecular system. Table 5 lists the atomic charge of the title compound as determined by B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) level of theory. The investigation of Mulliken charges has been created to describe the distribution of atomic charges in molecular wave functions. They mostly utilize an LCAO MO method and first-order density functions [31]. As result, we found that charges on atoms Br1, C3, C4, C6, C7, C13, C18, C20, O22, O24, C26, C28, and C29 are negative, whereas, C2, C10, C12, C14, C16, C21, C23, C25 are positive. The surrounding atoms that the analyzed molecule hydrogen atoms were connected to result in a slight variance in their charges. Fukui function analysis was also performed because it is a crucial parameter in figuring out the molecule's nucleophilic and electrophilic tendencies. The Mulliken population analysis (MPA) method can be utilized to obtain the individual charge value for the Fukui functions. Fukui functions can be computed using the following formulas:

| (2) |

Table 5.

Mulliken Atomic Charge distribution, Fukui Functions, and Local Softness equivalent to (0,1), (−1,2), and (1,2) charge and multiplicity of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

| Atom | Mulliken Atomic Charges |

Fukui Functions |

Local Softness |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (0,1) | N-1 (+1,2) | N + 1(−1,2) | fr+ | fr- | Δf | fr0 | sr+ fr+ | sr- fr- | sr0 fr0 | |

| Br1 | −0.185831 | 0.009074 | −0.269503 | −0.08367 | −0.19491 | 0.11124 | −0.27404 | −0.04471 | −0.10415 | −0.14644 |

| C2 | 0.099355 | 0.169780 | 0.076829 | −0.02253 | −0.07043 | 0.0479 | −0.00806 | −0.01204 | −0.03763 | −0.00431 |

| C3 | −0.601214 | −0.605372 | −0.596343 | 0.004871 | 0.004158 | 0.000713 | −0.29366 | 0.002603 | 0.002222 | −0.15692 |

| C4 | −0.745296 | −0.725910 | −0.773333 | −0.02804 | −0.01939 | −0.00865 | −0.41038 | −0.01498 | −0.01036 | −0.21929 |

| C6 | −0.170501 | −0.160778 | −0.185550 | −0.01505 | −0.00972 | −0.00533 | −0.10516 | −0.00804 | −0.00519 | −0.05619 |

| C7 | −0.620599 | −0.590195 | −0.608571 | 0.012028 | −0.0304 | 0.042428 | −0.31347 | 0.006427 | −0.01624 | −0.16751 |

| C10 | 0.815352 | 0.839841 | 0.799771 | −0.01558 | −0.02449 | 0.00891 | 0.379851 | −0.00833 | −0.01309 | 0.202977 |

| C12 | 0.133767 | 0.155988 | 0.156586 | 0.022819 | −0.02222 | 0.045039 | 0.078592 | 0.012194 | −0.01187 | 0.041996 |

| C13 | −0.063020 | 0.017020 | −0.124586 | −0.06157 | −0.08004 | 0.01847 | −0.1331 | −0.0329 | −0.04277 | −0.07112 |

| C14 | 0.438172 | 0.422447 | 0.503799 | 0.065627 | 0.015725 | 0.049902 | 0.292576 | 0.035068 | 0.008403 | 0.156341 |

| C16 | 0.246084 | 0.179110 | 0.332623 | 0.086539 | 0.066974 | 0.019565 | 0.243068 | 0.046243 | 0.035788 | 0.129886 |

| C18 | −0.443595 | −0.395914 | −0.545247 | −0.10165 | −0.04768 | −0.05397 | −0.34729 | −0.05432 | −0.02548 | −0.18558 |

| C20 | −0.400033 | −0.365840 | −0.502941 | −0.10291 | −0.03419 | −0.06872 | −0.32002 | −0.05499 | −0.01827 | −0.17101 |

| C21 | 0.383341 | 0.387183 | 0.381358 | −0.00198 | −0.00384 | 0.00186 | 0.187767 | −0.00106 | −0.00205 | 0.100335 |

| O22 | −0.226272 | −0.193913 | −0.328510 | −0.10224 | −0.03236 | −0.06988 | −0.23155 | −0.05463 | −0.01729 | −0.12373 |

| C23 | 0.145310 | 0.161232 | 0.163767 | 0.018457 | −0.01592 | 0.034377 | 0.083151 | 0.009863 | −0.00851 | 0.044433 |

| O24 | −0.232015 | −0.151500 | −0.338671 | −0.10666 | −0.08052 | −0.02614 | −0.26292 | −0.05699 | −0.04303 | −0.14049 |

| C25 | 0.067260 | 0.070466 | 0.011937 | −0.05532 | −0.00321 | −0.05211 | −0.0233 | −0.02956 | −0.00172 | −0.01245 |

| C26 | −0.014428 | −0.014058 | −0.066745 | −0.05232 | −0.00037 | −0.05195 | −0.05972 | −0.02796 | −0.0002 | −0.03191 |

| C28 | −0.456324 | −0.450301 | −0.479708 | −0.02338 | −0.00602 | −0.01736 | −0.25456 | −0.01249 | −0.00322 | −0.13603 |

| C29 | −0.417952 | −0.421279 | −0.437648 | −0.0197 | 0.003327 | −0.02303 | −0.22701 | −0.01053 | 0.001778 | −0.12131 |

Where (N) is neutral, (N + 1) is anionic, (N-1) is cationic chemical species, and qr is the charge of the atom at the rth atomic site. Whereas the radical attack, electrophilic and nucleophilic are denoted by the marks 0, +, and -, respectively. The Dual descriptor [f (r)] can be calculated using the formula presented below [32].

The results of the Fukui function analysis, which are listed in Table 5 were derived from the NBO charges. The negative values of the Fukui function demonstrate that when an electron is added to a molecule, certain parts experience a reduction in electron density, while other regions experience an increase in electron density. The electrophilic, as well as nucleophilic sites in the molecule are reactive in the sequence shown by the estimated value in Table 5. The following is the order:

-

a)

Electrophilic reactivity order: C4 > C7 > C3 > C28 > C18 > C29 > C20 > O24 > O22 > Br1 > C6 > C13 > C26.

-

b)

Nucleophilic reactivity order: C3 > C14 > C21 > C16 > C23 > C12 > C25 > C2.

In comparing, the three forms of attack, the electrophilic attack within the molecule was far more reactive than the nucleophilic and radical attacks. The Fukui function was also used to calculate the values of the local softness, which are shown in Table 6. It aids in researching and disseminating knowledge about biological investigations, ligand-protein interactions, and protein folding [33], all of which are crucial in the field of medicine.

Table 6.

Theoretical energy values of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D by B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) method.

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| EHomo (eV) | −6.50754 |

| ELumo (eV) | −2.76480 |

| Ionization potential I (eV) | 6.50754 |

| Electron affinity A (eV) | 2.76480 |

| Energy gap (eV) | 3.74274 |

| Electronegativity χ (eV) | 4.63617 |

| Chemical potential µ (eV) | - 4.63617 |

| Chemical hardness η (eV) | 1.87137 |

| Chemical softness S (eV)−1 | 0.53436 |

| Electrophilicity index ω (eV) | 5.74287 |

3.8. HOMO-LUMO analysis

The terms highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) refer to a molecule's ionization potential and electron affinity, respectively. The HOMO-LUMO energy gap determines the molecule stability, electron-donating nature, and acceptor nature [34]. Fig. 8 displays a graphical representation of HOMO and LUMO. Calculations are made for the titled compound additional significant properties, including its electron affinity, electronegativity, ionization and chemical potential, chemical hardness and softness, and electrophilicity index. Table 6 lists the aforementioned characteristics. According to this table, the HOMO orbital, which has many electrons with energy of −6.507 eV, donates electrons to the LUMO orbital, which has fewer electrons with energy of −2.764 eV, and the energy gap between the two is 3.743 eV. This indicates the stability of our compound, although band gap validate the eventual charge transfer interactions [35].

Fig. 8.

HOMO and LUMO with gap energy.

3.9. UV–Visible analysis

Investigations of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D ultraviolet analysis and energy characteristics were studied using the B3LYP and CAM-B3LYP. Two solvents (ACN and DMSO) and the gas phase were used for the research. Calculated and observed UV graphs of the subject molecule are presented in Fig. 9 (A-C), and the results, together with wavelengths (nm), excitation energies (eV), oscillator strengths (f), HOMO-LUMO energies, the key transition contributions, and energy gap, are summarized in Table 7. Transitions for the UV area in the gas phase, ACN, and DMSO solvents are predicted by DFT calculations. By using B3LYP, the most likely transition for the gas phase is from H→L at 402.90 nm (3.077 eV), with a contribution of 86.8%. The two other transitions are H-1→L at 362.44 nm (3.420 eV), with a contribution of 82.12%, and H-2→ L at 335.68 nm (3.693 eV), with a contribution of 58.73%. The transition with the highest transition in ACN solution is 403.70 nm (3.071 eV), which contributes 91.48%. The two other transitions are H-1→L at 354.73 nm (3.495 eV), which contributes 83.8%, and H-3→L at 328.33 nm (3.776 eV), which contributes 49.2%. The most likely transition in DMSO is from H→L at 403.80 nm (3.070 eV), contributing 91.5%, followed by H-1→L at 354.69 nm (3.495 eV), contributing 83.7%, and H-3→L at 328.26 nm (3.777 eV), and contributing 50.4%. Through CAM-B3LYP the most intense electronic transition at 281 nm and 281.19 nm in ACN and DMSO solvents These theoretical findings have experimental absorbance wavelengths associated with them of 289 and 290.20 nm, respectively.

Fig. 9.

(A) Theoretical (B,C) Experimental UV–Vis spectra of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

Table 7.

Comparison of electronic properties of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D attained experimentally and calculated by TD-DFT/B3LYP method.

| Experimental | TD-B3LYP/6311++G(d,p) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax (nm) | Band gap (eV) | λmax (nm) | Band gap (eV) | Oscillatory Strength | Assignments | |

| Gas | 402.90 | 3.0773 | 0.0165 | H→L (86.8%) | ||

| 362.44 | 3.4209 | 0.0049 | H-1→L (82.12%) | |||

| 335.68 | 3.6935 | 0.0023 | H-2→L (58.73%) | |||

| ACN | 289 | 4.29 | 403.70 | 3.0712 | 0.0213 | H →L (91.48%) |

| 354.73 | 3.4951 | 0.0097 | H-1→L (83.8%) | |||

| 328.33 | 3.7762 | 0.0008 | H-3→L (49.2%) | |||

| DMSO | 290.20 | 4.27 | 403.80 | 3.0705 | 0.0222 | H→L (91.5%) |

| 354.69 | 3.4956 | 0.0101 | H-1→L (83.7%) | |||

| 328.26 | 3.7770 | 0.0008 | H-3→L (50.4%) | |||

| TD—CAM-B3LYP/6311++G(d,p) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACN | 289 | 4.29 | 333.08 | 3.7223 | 0.0242 | H→L (41.6%) |

| 325.11 | 3.8136 | 0.0043 | H-4→L (44.3%) | |||

| 281.00 | 4.4122 | 0.1361 | H→L (43.4%) | |||

| DMSO | 290.20 | 4.27 | 333.10 | 3.7221 | 0.0255 | H→L (41.9%) |

| 325.08 | 3.8140 | 0.0045 | H-4→L (44.8%) | |||

| 281.19 | 4.4093 | 0.1456 | H→L (42.8%) | |||

3.10. Thermodynamical properties

The relationships between the energy, structural, and relativistic aspects of the titled molecule are provided by the thermodynamic constraints of the compounds. The standard thermodynamic properties: Gibbs free energy (Go), entropy (S), and enthalpy (H) were derived on the ground of vibrational analysis and statistical thermodynamics, and the thermodynamic constraints were gathered up to 500 K. The values of H and S are increases and the value of G decreases with rise in temperatures from 100 to 500 K, as seen in Table 8, which is explained by the increase of molecular vibration as temperature rises [36]. Fig. 10 reveals the relationships between the thermodynamic properties. High levels of randomness inside the molecules as a result of an increase in entropy demonstrate an intermolecular reaction, and the chemical reaction takes place as a result of the distinctive change in enthalpy. The correlation equations between these thermodynamic characteristics and temperatures, as well as the accompanying fitting equations and fitting factors that are all over 0.999, are also provided below, along with the quadratic formulas used to fit them. Fig. SF3-SF5 displays the correlations plot of the title molecule thermodynamic parameters.

Table 8.

Temperature dependence of thermodynamic properties of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D at B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p).

| T(K) | G0p, m x10 (J/ mol K) | S0m(J/ mol K) | H0m(kJ/ mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 637.7253 | 360.66 | 673.7846 |

| 200 | 599.1906 | 444.13 | 688.0536 |

| 300 | 552.7901 | 523.97 | 709.9560 |

| 400 | 498.981 | 603.75 | 739.8756 |

| 50 | 436.098 | 682.16 | 777.1635 |

Fig. 10.

Graphical representation of (Go), (So), and (Ho) on temperature of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D .

All the thermodynamic information is valuable for further research on the compounds mentioned in the title. In the thermochemical field, they calculate additional thermodynamic energy in line with thermodynamic function relationships and forecast the course of chemical reactions in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics. Since they could not be applied to solutions, all thermodynamic calculations were performed in the gas phase [37].

3.11. Hirshfeld surface analysis (HF) and interaction energy calculation

Using Crystal Explorer 17.5 [10], the HF surfaces and their related 2D fingerprint plots (FPs) were created. With the use of dnorm (normalized contact distance) and 2D FPs, the quantification and decoding of the intermolecular interactions in the crystal packing are respectively displayed. Short interatomic contacts cause the dark red dots to form on the dnorm surface, but other intermolecular interactions cause light red spots to appear. In relation to the respective van der Waals radii, the distances di (inside) and de (outside) from the nuclei to the HF surface are represented. Fig. 11 shows the Hirshfeld surface (HF) mapped across dnorm in the range from −0.2367 to 1.3535. Table ST5 provides details about the intermolecular interactions, which are depicted as spots on the HF surface (Fig. 11). For instance, the C—H—O contacts are responsible for the distinct circular depressions (red dots), whereas the H—H contacts are responsible for the white spots. Further chemical understanding of molecular packing is provided by the useful curvature metrics shape-index (( Fig. 11 (D) and curvedness (Fig. 11 (E)) developed by Koendrink [38]. Low surface curvature indicates a flat area and maybe a hint of pi…pi stacking in the crystal. The deficiency of pi…pi stacking is shown by an HF surface with strong curvedness, which is accentuated by dark-blue edges. The shape index, a qualitative measure of shape, is perceptive to minute variations in surface shape, especially when applied to flat areas. 2D FPs can be broken down to reveal close interactions. This decomposition makes it possible to separate each contribution from the total fingerprint resulting from various interactions. The fingerprint map shows clear complementary sections where one of the molecules serves as a donor (de>di) and the 2nd serves as an acceptor (de<di). The 2D FPs of the titled compound ( Fig. 12 ) show strong intermolecular interactions that are H—H, C—H, O—H, Br-H, C-Br, and Br-H. The average contribution to the H—H contacts, on the other hand, is 32.6% and they are relatively homogeneously extended throughout a wide range of (di, de) pairings ( Fig. 12 (A). However, with an average of 17.5 and 14.6%, respectively, O…H/H…O and H…Br/Br…H contacts show substantially a sharp and a circular distribution ( Fig. 12 (B, C). Intermolecular interactions C…Br/Br…C and Br…O/O…Br shows up as brief blue patches with proportions of 2.2 and 2.6%, respectively ( Fig. 12 (D, F). Additionally widely spread are the C…H/H…C contacts, with accumulation comprising about 19.5%. ( Fig. 12 (E). Additionally, O…C interactions are insignificant and barely show 0.2%. The color gradient (blue to red) in the FPs represents the relative share of the contacts over the surface Table ST6. The calculation of pair-wise interaction energies inside a crystal may now be done using a new tool added to Crystal Explorer 17.5 [10] that combines the energies of four different types of interactions, including exchange-repulsion (Erep), polarization (Epol), dispersion (Edis), and electrostatic (Eele). This calculation is based on a single-point molecular wave function at B3LYP/6–31G(d,p). Around the molecule, a cluster with a radius of 3.8 Å was created, and an energy calculation was run. The surrounding molecules (density matrices) are created within this shell by using crystallographic symmetry operations with respect to the main molecule (density matrix). In addition to these energy data, the generated table also contains other data that can be used to calculate the lattice energy of a crystal, such as the number of pairs of interacting molecules with respect to the reference molecule (N), the centroid-to-centroid distance between the reference molecule and interacting molecules (R), and the existence of rotational symmetry operations with respect to the reference molecule (Symp).

Fig. 11.

Hirshfeld surface for 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D mapped with (A) dnorm (B) di (C) de (D), shape index (E) curvedness (F), Fragment patches.

Fig. 12.

2-D fingerprint plot of different contributions for 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

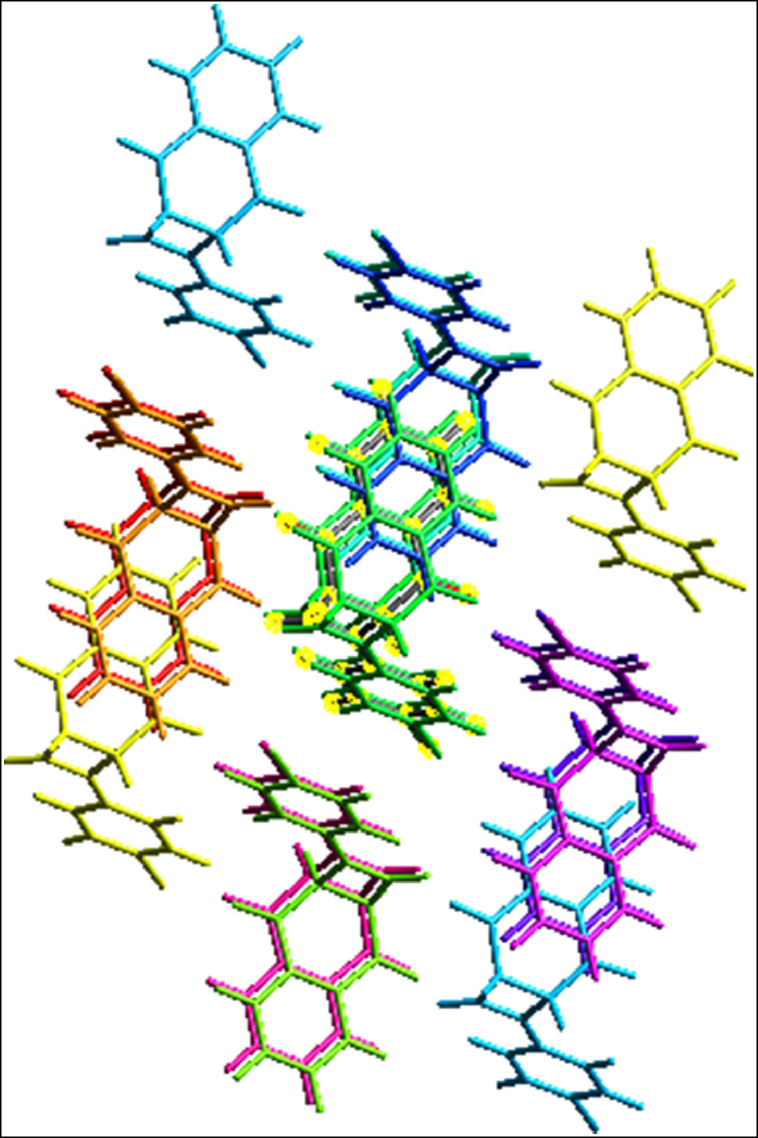

The findings of the calculations of interaction energies are displayed in Table 9. These findings suggest that there are eleven categories in which the interactions between the main molecule and its neighbors can be divided. In Fig. 13, the colors of the molecules in each of these groups can be used to distinguish them. The total interaction energies are assessed using the molecular pair-wise interaction energies computed for the building of energy frameworks. The overall interaction energies are electrostatic (Eele = −79.1KJ mol−1), polarization (Epol = −18.6 KJ mol−1), dispersion (Edis = −304.5KJ mol−1), repulsion (Erep = 216 KJ mol−1) and total interaction energy (Etot = −229.1 KJ mol−1).

Fig. 2.

2D docking images of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D embedded in the active sites of 7Y5T.

Table 9.

Calculations of interaction energies.

| N | Symop | R | Electron Density | Eele | Epol | Edis | Erep | Etot | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 7.80 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −18.9 | −5.7 | −31.7 | 36.4 | −29.3 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 11.70 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −6.9 | −1.8 | −7.7 | 4.1 | −12.8 | |

| 2 | x, y, z | 8.39 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −4.8 | −1.4 | −10.7 | 4.8 | −12.4 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 7.47 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −8.1 | −1.0 | −44.2 | 32.8 | −27.5 | |

| 2 | x, y, z | 7.32 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −2.3 | −0.9 | −22.1 | 12.3 | −14.8 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 7.22 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −7.4 | −1.8 | −61.5 | 34.5 | −41.5 | |

| 2 | x, y, z | 11.88 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −1.9 | −0.5 | −10.2 | 6.3 | −7.4 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 9.97 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −9.0 | −1.9 | −63.1 | 44.6 | −38.3 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 7.17 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −12.5 | −1.3 | −32.0 | 31.4 | −22.7 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 6.93 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −5.7 | −2.1 | −15.6 | 6.5 | −17.1 | |

| 1 | -x, -y, -z | 11.74 | B3LYP/6–31G(d,p) | −1.6 | −0.2 | −5.7 | 2.4 | −5.3 |

Fig. 13.

The color-coded interaction mapping within 3.8 A˚ of the centring S1 (marked by an asterisk) molecular cluster.

3.12. Calculations of chemical shifts

The Gauge-Independent Atomic Orbital (GIAO) approach [39] at the DFT/B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) level in CDCl3 was used to determine the 1H and 13C chemical shift values (Fig. SF6(A, B)). Using the equivalent TMS shielding calculation at the same theoretical level as the reference, the relative chemical shifts were determined (λ= λTMS - λcalc). Table 10 lists the experimental and estimated 1H and 13C chemical shift values for the 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D molecule (Fig. 14 (A, B)). The 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D molecule 1H NMR spectra in CDCl3 revealed bands for aromatic protons in the range of 8.16–7.40 ppm. The chemical changes predicted by B3LYP/GIAO/6–311++G(d,p) are in the range of 8.56–7.54 ppm. The observed values for the cyclobutene ring protons are 4.51 and 4.13 ppm, while the calculated values are 4.48 and 4.37 ppm. Between 134.3 and 127.1 ppm are the predicted values for the aromatic carbon signals that were observed between 134.7 and 127.1 ppm. The calculated values for the cyclobutene carbons are 148.6 to 49.7 ppm, while the actual values range from 148.0 to 49.1 ppm. The calculated value of the carbonyl carbons is 195.7 ppm, while the observed value is 195.3 ppm. The correlation coefficients (R) between experimental and predicted data demonstrate that protons and carbon atoms have identical linear connections, with R2 = 0.996.

Table 10.

Experimental and calculated 1H and 13C chemical shift values of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D (ppm).

| Atoms | Experimental chemical shift (ppm) | Calculated chemical shift (ppm) | Degeneracy (ppm) | RMSD (R) and R2 Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30H | 8.16 | 8.56 | 1.000 | For 1H |

| 27H | 8.08 | 8.37 | 1.000 | R = 0.998 |

| 11H | 7.80 | 7.88 | 2.000 | R2=0.996 |

| 32H | 7.80 | 7.88 | 2.000 | |

| 31H | 7.48 | 7.92 | 1.000 | |

| 9H | 7.47 | 7.66 | 1.000 | |

| 8H | 7.42 | 7.60 | 1.000 | |

| 5H | 7.40 | 7.54 | 1.000 | |

| 15H | 6.59 | 6.90 | 1.000 | |

| 17H | 4.51 | 4.48 | 1.000 | |

| 19H | 4.13 | 4.37 | 1.000 | |

| 18C | 195.3 | 195.5 | 1.000 | |

| 20C | 195.3 | 195.7 | 1.000 | For 13C |

| 12C | 148.0 | 148.6 | 1.000 | R = 0.998 |

| 2C | 134.7 | 134.3 | 1.000 | R2=0.996 |

| 29C | 133.8 | 133.7 | 1.000 | |

| 28C | 133.8 | 133.0 | 1.000 | |

| 21C | 131.8 | 131.7 | 1.000 | |

| 23C | 131.8 | 131.6 | 1.000 | |

| 4C | 130.8 | 130.8 | 1.000 | |

| 3C | 130.8 | 130.7 | 1.000 | |

| 10C | 129.3 | 129.4 | 1.000 | |

| 7C | 127.8 | 127.5 | 1.000 | |

| 6C | 127.8 | 127.5 | 1.000 | |

| 25C | 127.6 | 127.4 | 1.000 | |

| 26C | 127.1 | 127.1 | 1.000 | |

| 13C | 123.4 | 123.2 | 1.000 | |

| 14C | 52.1 | 52.6 | 1.000 | |

| 16C | 49.1 | 49.7 | 1.000 |

Fig. 14.

(A) Experimental 1H of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D. (B) Experimental 13C of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D.

3.13. Molecular docking

Molecular docking is a method for finding new medications that determines the most likely binding location and affinity of therapeutic substances for protein targets. Both the prediction of ligand conformation pose and the evaluation of binding affinity in terms of binding energy are aided by the molecular docking approach. The three-dimensional crystal structures of the target proteins were retrieved using the Protein Data Bank in PDB format (http://www.rscb.org.pdb). The target proteins' PDB IDs are PY84, 7Y5T, and 7C9I. The pertinent target protein ID was selected from the Swiss ADMETarget prediction site and retrieved from the protein data bank. It was docked with a ligand that was similar to 1-(4-BP) DHCBN-3,8-D. The chosen proteins (PY84, 7Y5T, and 7C9I) were all selected using the same string of ligand (PDB). The ligands that have already been bound just inside proteins are the active docking sites. All molecular docking calculations were performed using AUTODOCK vina and chimera [14] and the default exhaustiveness value 8 used for docking. The Auto-Dock Tools graphical user interface was used to eliminate the ligand and water molecules that were present in the target proteins. Additionally, it is used to impart Kollman charges and polar hydrogen bonds to specific proteins [15], [16], [17]. The energy-minimized molecular structure of the 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D) molecule was used to create the ligand PDB file. The intermolecular energy, binding energy, and inhibition constant of the compound in relation to the targeted proteins are shown in Table 1 . The binding interactions between the 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D) ligand and various protein targets are shown in Fig. 1 - 3 . The docking results in Table 1 indicate the best mode of binding between the ligand molecule and the PY84, 7Y5T, and 7C9I (receptors) proteins, with binding energies of −6.7 Kcal/mol, −7.8 Kcal/mol, and −7.7 Kcal/mol, respectively. The 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D) molecule had lower binding energies for the aforementioned protein targets and the greatest binding affinity and antiviral effectiveness against PY84, 7Y5T, and 7C9I. According to these results, the ligand 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D) may be exploited as a therapeutic target to stop viral replication. 7Y5T, with a small variation, has a greater binding energy than PY84 and 7C9I when compared to other proteins. The biological activity of the molecule is confirmed by the docking of all 3 proteins with the 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D) ligand. The coordintaes of binding sites of ligand with 7Y5T are center_x = 165.00, center_y = 170.00, center_z = 145.00 and size_x = 25, size_y = 25, size_z = 25. The docking analysis shows that the title molecule, with its high binding energy structure, exhibits strong biological activity as an antiviral agent. In this docking process protein considered as a rigid entity while the ligand is considered flexible, i.e. sp3 bonds are able to rotate, but bond lengths and bond angles are kept fixed.

Table 1.

Molecular docking of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D with target proteins.

| Sr. No. | Protein ID | Residue | Inhibition constant (micromolar) | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6Y84 | 1 | 12.048 | −6.7 |

| 2 | 7Y5T | 1 | 1.876 | −7.8 |

| 3 | 7C9I | 1 | 2.222 | −7.7 |

Fig. 1.

2D docking images of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D embedded in the active sites of PY84.

Fig. 3.

2D docking images of 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D embedded in the active sites of 7C9I.

3.14. Molecular dynamic simulation (MDS) and binding energy

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a prediction in which we calculate how every atom in a protein or in molecular system will move over time. The ligand-protein docked complex that showed the highest binding affinity with strong hydrogen bonding was further subjected to all atom 20 ns molecular dynamic simulations, due to system limitation we could present here only 20 ns MDS only. The NVIDIA RTX 3060ti GPU-accelerated GROMACS 2022 software was utilized in the current study. The protein topology was produced using the CHARMM27 force field. The ligand topology and gromacs compliant files were created using the Swiss Param Server (https://www.swissparam.ch/) [18,19]. Each system was solvated using the TIP3P [40] water model before being neutralized with the proper concentrations of Na + and Cl -ions. The energy of each system was then reduced using the steepest descent minimization algorithm, which has a maximum step count of one mil- lion and/or force below 10.0 kJ/mol. Each system underwent the ensemble equilibration process at 1 ns NVT and 1 ns NPT. The solvent molecules were permitted to flow freely in order to achieve solvent equilibration in the system. With a 1.2 nm cut-off and 1.2 nm Fourier spacing, Particle Mesh Eshwald (PME) was taken into consideration for the capturing of long-range electrostatic inter- actions. The equilibrated system underwent a 20 ns MD simulation. The system was heated to 300 K using the V-rescale weak coupling approach. The Parrinello Rahman approach was used to set the pressure of each system at 1 atm. [41]. The docked protein-ligand combination of the molecule with the PDB ID: PY84 was used to assess the stability of the medication 1-(4-BP)DHCBN-3,8-D. Force-fields are utilized in molecular dynamics simulations to model the bonded and non-bonded interactions of biomolecules in an effort to comprehend their dynamics, interactions, and stability [20]. As a result, it was demonstrated that during simulation eight hydrogen bonds formed (all the residues involved in making hydrogen bonds are presented in the Table SF7) and it may be predicted that beyond the 20 ns it is a better chance for ligand to stabilized more and may form more hydrogen bonds since at 20 ns ligand gots more stability in comparison to initial. RMSD is a vital factor in MD simulation. It is used to determine if complex structures are stable in relation to model protein backbone architectures. Fig. SF1 displays the RMSD values for carbon backbone complex (protein + drug) structures relative to bare protein in the time trajectory 0–1 ns. In this short time frame the complex stability is implied by the RMSD stabilization in Fig. SF1. As can be seen from the graph, the RMSD for the complex (protein + drug) varies in comparison to protein, indicating the likelihood of fluctuation when the ligands are binding to protein. The complex structure and the host protein RMSD values overlap, may indicate a stable docking between the two. The protein and ligand establish hydrogen bonds that determine the strength of the complex (Fig. SF2). The amount of hydrogen found is exactly in line with the docking findings, which further supports stability. All MD simulation data demonstrate that PY84 may effectively assemble a stable protein complex after interacting with the active regions of proteins. The short range Lennard-Jones energy is −83.6 ± 6.4 kJ mol−1, while the average short range coulombic interaction energy is −22.5 ± 3.2 kJ mol−1. But in this situation, the entire contact energy is useful. The result is −106.1 ± 9.6 kJ mol−1 after propagating the error in accordance with the common formula for adding two numbers.

4. Conclusion

In the current work, studies on thermodynamic characteristics, docking, NMR (13C and 1H), NBO, and vibrational spectroscopy (FT-IR and UV) were conducted. The VEDA analysis indicates the presence of 32 atoms and 90 normal vibration modes in 1-(4-BP) DHCBN-3,8-D. The PED values show that the estimated wave numbers are 1673 cm−1 and 1665 cm−1 with 62% and 64%, PED% contributions respectively. The Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analyses indicate the stronger propensity of donors to contribute with 19.38 kcal/mol stabilizing energy of delocalization. On the other hand, Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) map reveals the areas of strongest attraction (H atoms) and strongest repulsion (O atoms) with the color code range of −4.426a.u and +4.426a.u respectively referring to the potential reactive sites and biologically activity of the molecule. TD-DFT calculations disclose the HOMO-LUMO energy gap of 3.743 eV, demonstrating the exceptional stability of 1-(4-BP) DHCBN-3,8-D and the presence of charge transfer within the molecule. The 2D Fingerprint plots reveal the existence of H—H, C—H, O—H, Br-H, C-Br, and Br-H intermolecular interactions and total energy of (Etot = −229.1 KJ mol−1) pertaining to electrostatic, polarization, dispersion, repulsion interactions. The GIAO analysis demonstrate that protons and carbon atoms have identical linear connections, with R2 = 0.996. The molecular docking study predicts the stability and strong binding efficiency between the ligand 1-(4-BP) DHCBN-3,8-D and the protein PY84 corresponds to −6.7 kcal/mol. Over all, the study reveals the efficiency of the title molecule (1-(4-BP) DHCBN-3,8-D) which could give rise to novel structural motifs and furnish lead candidates for the treatment of the Covid-19 diseases.

Credit author statement

Shaghaf Mobin Ansari: Calculations, Visualization, Plotting graphs and editing. Ghazala Khanum: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Investigation. Muneer-Ul-Shafi Bhat: Experiment, Writing - review & editing. Masood Ahmad Rizvi: Editing, Supervision, Validation. Noor U Din Reshi: Data curation, Resources. Majid Ahmad Ganie: Writing - review & editing. Saleem Javed: Conceptualization, Methodology. Bhahwal Ali Shah: Software, Editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135256.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data Availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.(a) Bolton J.L., Dunlap T. Formation and Biological Targets of Quinones: cytotoxic versus Cytoprotective Effects. chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017;30:13–37. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Madeo J., Zubair A., Marianne F. A review on the role of quinones in renal disorders. Springerplus. 2013;2:139. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Zhu H., Yunbo L. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 and its potential protective role in cardiovascular diseases and related conditions. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2012;12:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s12012-011-9136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheng S.-.T., Hu J.-.L., Ren J.-.H., Yu H.-.B., Zhong S., Wong V.K.W., Law B.Y.K., Chen W.-.X., Xu H.-.M., Zhang Z.-.Z., Cai X.-.F., Hu Y., Zhang W.-.L., Long Q.-.X., Ren F., Zhou H.-.Z., Huang A.-.L., Chen J. Dicoumarol, an NQO1 inhibitor, blocks cccDNA transcription by promoting degradation of HBx. J. Hepatol. 2021;74:522–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Sridhar J., Liu J., Foroozesh M., Stevens C.L.K. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes by quinones and anthraquinones. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012;25:357–365. doi: 10.1021/tx2004163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee W.-.S., Ham W., Kim J. Roles of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 in diverse diseases. Life. 2021;11:1301. doi: 10.3390/life11121301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Vasilios M. Polymeropoulos, a potential role of coenzyme Q10 deficiency in severe SARS-CoV2 infection. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2020;5(4) [Google Scholar]; (b) Ahmed M.H., Hassan A. Dexamethasone for the treatment of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a review. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2020;2:2637–2646. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00610-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tutusaus A., Marí M., Ortiz-Pérez J.T., Nicolaes G.A.F., Morales A., de Frutos P.G. Role of vitamin K-dependent factors protein S and GAS6 and TAM receptors in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-associated immunothrombosis. Cells. 2020;9:2186. doi: 10.3390/cells9102186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.K.S. Hansen, T.H. Mogensen, J. Agergaard, B.S.-Christensen, L.Østergaard, L.K. Vibholm, S. Leth, High-dose coenzyme Q10 therapy versus placebo in patients with post COVID-19 condition: a randomized, phase 2, crossover trial, The Lancet Regional Health - Europe (2022) 100539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery J.A., Jr., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Keith T., Kobayashi R., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas O., Foresman J.B., Ortiz J.V., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford: 2013. GAUSSIAN 09. Revision E.01. [Google Scholar]

- 8.R. Dennington, T. Keith, J. Millam, GaussView, Version 5, Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, 2009.

- 9.M.H. Jomroz, Vibrational Energy Distribution Analysis, VEDA4, Warsaw, 2004.

- 10.Turner M.J., McKinnon J.J., Wolff S.K., Grimwood D.J., Spackman P.R., Jayatilaka D., Spackman M.A. The University of Western Australia; 2017. CrystalExplorer17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glendening E.D., Badenhoop J.K., Reed A.D., Carpenter J.E., Weinhold F. Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University. Wisc. Madison; 2001. NBO 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neese F. The ORCA program system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012;2:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a). Tian Lu, Feiwu Chen, Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer, J. Comput. Chem. 33 (2012) 580-592. (b). Origin 8.0, OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.(a) Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trott O., Olson A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKinnon J.J., Jayatilaka D., Spackman M.A. Towards Quantitative Analysis of Intermolecular Interactions with Hirshfeld Surfaces. Chem. Comm. 2007;37:3814–3816. doi: 10.1039/b704980c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumus M., Babacan S.N., Demir Y., Sert Y., Koca I., Gulc I. In, discovery of sulfadrug-pyrrole conjugates as carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Archiv Der Pharm. 2022;355 doi: 10.1002/ardp.202100242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dege N., Gokce H., Dogan O.E., Alpaslan G., Agar T., Muthu S., Sert Y. Quantum computational, spectroscopic investigations On N-(2-((2-Chloro-4, 5-Dicyanophenyl)Amino)Ethyl)-4-methylbenzenesulfonamide by DFT/TD-DFT with different solvents, molecular docking and drug-likeness researches. Coll. and Surf. A: Physicochem. and Eng. Aspects. 2022;638 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zoete V., Cuendet M.A., Grosdidier A., Michielin O. SwissParam: a fast force field generation tool for small organic molecules. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:2359–2368. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjelkmar P. Implementation of the CHARMM force field in GROMACS: analysis of protein stability effects from correction maps, virtual interaction sites, and water models. J. of Chem. Theory and Comput. 2010;6(2):459–466. doi: 10.1021/ct900549r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh P., Sharma P., Bisetty K., Perez J.J. Molecular dynamics simulations of Ac-3Aib-Cage-3Aib-NHMe. Mol. Simul. 2010;36:1035–1044. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunasekaran S., Sailatha E. FTIR, FT Raman spectra and molecular structural confirmation of isoniazid. Indian J. Pure Appl. Phys. 2009;47:12–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanak H., Ersahin F., Agar E., Buyukgungor O., Yavuz M. X-Ray structure analysis online. Anal. Sci. 2008;24:237. [Google Scholar]

- 23.G. Varsanyi, Vibrational Spectra of Seven Hundred Benzene Derivatives Academic Press,

- 24.Barnes A.J., Majid M.A., Stuckey M.A., Gregory P., Stead C.V. The resonance Raman spectra of Orange II and Para Red: molecular structure and vibrational assignment. Spectrochim. Acta A. 1985;41(4):629–635. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mooney E.F. The infra-red spectra of chloro- and bromobenzene derivatives—II. Nitrobenzenes, Spectrochim. Acta. 1964;20:1021–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bopp F., Meixner J., Kestin J. 5th ed. Academic Press Inc. (London)Ltd.; New York: 1967. Thermodynamics, and Statistical Mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthu S., Paulraj E.Isac. Spectroscopic and molecular structure (monomeric and dimeric structure) investigation of 2-[(2-hydroxyphenyl) carbonyloxy] benzoic acid by DFT method: a combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Mol. Struct. 2013;1038:145–162. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szafran M., Komasa A., Admska E.B. Crystal and molecular structure of 4-carboxypiperidinium chloride (4-piperidinecarboxylic acid hydrochloride. J. Mol. Struct. Theochem. 2007;827:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shainyan B.A., Chipanina N.N., Aksamentova T.N., Oznobikhina L.P., Rosentsveig G.N., Rosentsveig G.I.B. Intramolecular hydrogen bonds in the sulfonamide derivatives of oxamide, dithiooxamide, and biuret. FT-IR and DFT study, AIM and NBO analysis. Tetrahedron. 2010;66(44):8551–8556. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajagopalan N.R., Krishnamoorthy P., Jayamoorthy K. Bis (thiourea) strontium chloride as promising NLO material: an experimental and theoretical study. Karbala Inter.J. Mod. Sci. 2016;2(4):219–225. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pople J.A., Beveridge D.L. Vol. 96. McGraw Hill; New York: 1970. p. 91. (Approximate Molecular Orbital Theory). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukui K. Role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. Science. 1982;218:747–754. doi: 10.1126/science.218.4574.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balachandar S., Dhandapani M. Biological action of molecular adduct pyrazole:trichloroacetic acid on Candida albicans and ctDNA - A combined experimental, Fukui functions calculation and molecular docking analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1184:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renuga S., Karthikesan M., Muthu S. FTIR and Raman spectra, electronic spectra and normal coordinate analysis of N, N-dimethyl-3-phenyl-3-pyridin-2-yl-propan-1amine by DFT method. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014;127:439–453. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mary Y.S., Panicker C.Y., Sapnakumari M., Narayana B., Sarojini B.K., Al-Saadi A.A., VanAlsenoy C., War J.A., FT-IR N.B.O. HOMO-LUMO, MEP analysis and molecular docking study of 1-[3-(4-flfluorophenyl)-5-phenyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-pyrazol-1-yl] ethanone. Spectrochim. Acta. 2015;136:483–493. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nascimento J.P., Silva J.R.A., Lameira J., Alves C.N. Metal-dependent inhibition of HIV-1 integrase by 5CITEP inhibitor: a theoretical QM/MM approach. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013;583:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moro S., Bacilieri M., Ferrari C., Spalluto G. Autocorrelation of molecular electrostatic potential surface properties combined with partial least-squares analysis as an alternative attractive tool to generate ligand-based 3D-QSARs. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 2005;2:13–21. doi: 10.2174/1570163053175439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koenderink J.J. MIT Press; Cambridge MA: 1990. Solid Shape. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arcoria E., Maccarone G., Musumarra G. Tomaselli, Ultraviolet and infrared absorption spectra of 2-thiophenesulfonamides. Spectrochim. Acta 30A. 1974:611–618. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen W.L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J.D. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martyna G.J., Tobias D.J., Klein M.L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;101(5):4177–4189. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.