Abstract

Food-medicine products are important materials for daily health management and are increasingly popular in the global healthy food market. However, because of the biocultural difference, food-medicine knowledge may differ among regions, which hinders the global sharing of such health strategies. Aim at bridging the food-medicine knowledge in the East and West, this study traced the historical roots of food and medicine continuum of the East and West, which was followed by a cross-cultural assessment on the importance of food-medicine products of China, thereafter, the current legislative terms for food-medicine products were studied using an international survey. The results show that the food and medicine continuum in the East and West have their historical roots in the traditional medicines since antiquity, and the food-medicine knowledge in the East and West differs substantially; although the food-medicine products have common properties, their legislative terms are diverse globally; with proofs of traditional uses and scientific evidence, food-medicine products are possible for cross-cultural communication. Finally, we recommend facilitating the cross-cultural communication of the food-medicine knowledge in the East and West, thus to make the best use of the traditional health wisdom in the globe.

Keywords: cross-cultural communication, food and medicine continuum, food-medicine products, regulation, tradition

1. Introduction

Many foodstuffs are also with health-promoting effects, therefore, ‘food as medicine’ or ‘medicine as food’ are commonly seen, which have been recognized as the phenomenon ‘food and medicine continuum’ (Adelman and Haushofer, 2018, Etkin & Ross, 1982, Leonti, 2012). Products used as both food and medicine are thought to be pivotal materials in sustaining human health especially for the prevention of chronic diseases and geriatrics (Heinrich, Yao, & Xiao, 2022). While there is a steady increase in healthcare needs, such (local / regional) products have attracted more and more attention in the worldwide. In recent decades, we have seen that many of local / regional used food and medicine stuffs are turning into global market, such as goji (fruits of Lycium barbarum L., Gouqizi in Chinese) and reishi (Ganoderma, Lingzhi in Chinese) (Heinrich, Kum, & Yao, 2022, Yao, Heinrich, & Weckerle, 2018). However, because of the biocultural difference, people of the West and East have accumulated different knowledge on food and medicine continuum. Specifically, the used species, plant part used or usages may differ between the West and East (Heinrich, Yao, & Xiao, 2022). These differences have led to barriers for the cross-cultural communication of food and medicine knowledge between West and East.

Aiming at removing the cultural barrier, this study will analyze the differences in the knowledge of food and medicine continuum between the West and East from their historical roots and current regulations, thus, to facilitate the cross-cultural communication of ‘food and medicine continuum’ in the East and West.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Old tradition of food and medicine continuum

To study the old tradition of food and medicine continuum in the East and West, a thematic literature research was performed, which focused on the dietetic therapy in traditional Chinese medicine, Hippocratic and Galenic diet, and Ayurveda.

To disclose the different opinions on the traditional food-medicine products in the East and West, an expert of the western cultural background was invited to evaluate the food-medicine dual-use products in the official list of China. Accordingly, their importance for the usages of “healthy food”, “spice” and “medicine” in Europe was evaluated.

2.2. Current definition for interface of food and medicine in globe wide

To study the current definition for the interface of food and medicine in the globe wide, an international technical survey was conducted. (1) The following questions were prepared: How is food defined in your country? How is medicine defined in your country? Is there any intermediate categories of food and medicine in your country? What are the statutory documents for the regulation of food and medicine in your country? (2) Experts of food and medicine research or regulation from the following countries were consulted by e-mails: Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arab, Turkey, Nigeria, South Africa, Russia, European Union (EU), Canada, United States (US), Mexico and Brazil. (3) The responses were complied, and the referred statutory documents was searched, as a result, the stuffs in the interface of food and medicine were sorted out.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Old tradition of food and medicine continuum: Historical roots

3.1.1. Tradition of food and medicine continuum in the West

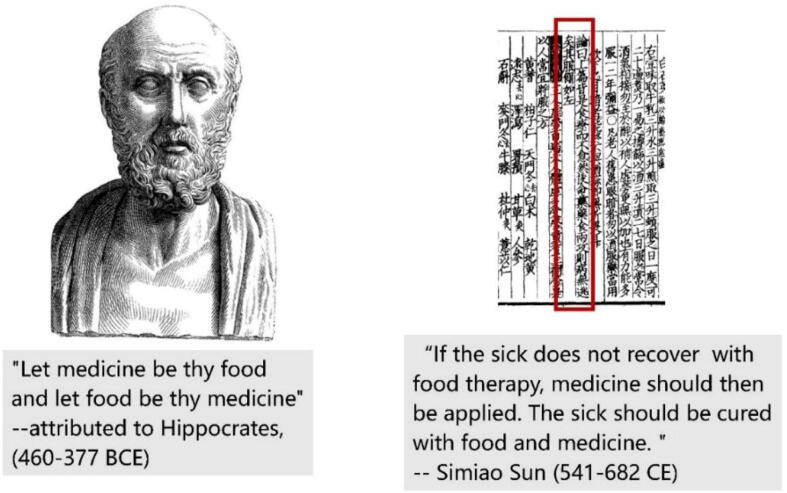

In the West, the knowledge of using herbs as food or medicine can be found in the historical medical texts. The Hippocratic Corpus might include the earliest records, which comprises about 60 medical texts written in around 5th to 4th century BCE (Totelin, 2021). There is a saying attributed to Hippocrates, “Let medicine be thy food and let food be thy medicine” (Fig. 1, left). The definitions of ‘food’ and ‘medicine’ were found in some texts of this collection; interestingly, food was subject to medicine at that time, along with pharmacology and surgery (Totelin, 2015). Touwaide and Appetiti (2015) analyzed the plant materials used in remedies included in this collection, to find that 33 of the 44 sampled medicinal plants are also used for nutritional purposes. Subsequently, this tradition developed and was succeeded by Galenic humoral food and medicine, which further influenced the Islamic medicine (Chen, 2008). In the Galenic humoral theory, all stuffs, whether food or medicine, were attributed with properties of warm, cool, dry or moist, so food and medicine were thought to be equal as a matter acting on human body. In his works of On the Powers of Food, Galen addressed the important function of nutrition in medical practice using the classic humoral ideas (Grant, 2002). Accordingly, it can be seen that ‘food and medicine continuum’ was prevalent since Antiquity in the West, and the boundary between food and medicine was blurry since then.

Fig. 1.

Typical old saying on food and medicine continuum in the West (left) and East (right).

3.1.2. Tradition of food and medicine continuum in the East

With its long history of civilization, China has the most influential traditional medicine system in the East. Thanks to the time-continuous Chinese herbals in the past two millennia, the knowledge of food and medicine continuum in the East still can be traced. The earliest record might be in Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica (Shén nóng běn cǎo jīng in Chinese) of the first century CE, in which 120 meteria medica was classified into “top grade”, hinting their uses as both food and medicine (Liu, Xiao, Qin, & Xiao, 2015). Dietary therapy, or Shizhi in Chinese, was first interpreted in one chapter of the medical monograph of Simiao Sun in the Tang Dynasty (Fig. 1, right) (Sun, 1998). Theoretically, all foodstuffs are endowed with taste(s), and the taste endows the foodstuff with functions, which is the same as the theory of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Additionally, it cited the viewpoints of Zhongjing Zhang, who was a famous doctor of the Han Dynasty, saying that the dietary therapy should be prior to the medical therapy. Moreover, this chapter also listed the fruits, vegetables, grains, and animal products with therapeutic uses. Later, the first monograph for dietary therapy, namely Shiliao Bencao in Chinese, was published, which elaborated the therapeutic foods and their usages (Meng & Zhang, 1984). The food-medicine tradition was succeeded in a series of dietary therapy herbals, such as Yinshan Zhenyao of the Yuan Dynasty, Jiuhuang Bencao of the Ming Dynasty, etc. In TCM, a medicinal material (or sometimes also used as food) is with traditional properties of four properties (ascending, descending, floating and sinking) and five tastes (pungent, sweet, sour, bitter and salty). With these properties, anything, whether used as food or medicine, can be used to balance the Yin-Yang of human body.

Food also plays an important role in Ayurveda, a traditional medical system stems from the South Asia subcontinent. The idea of dietary therapy was found in Charaka Samhita, an Ayurvedic classics of no later than 2nd century CE (Rastogi, 2014). Ayurvedic practitioners give advice on food based on diseases, the condition of diseases, and the status of dosha of individuals; moreover, the quantity of food should also be determined by both the digestibility of food and the digestive capacity of people (Kumar, Dobos, & Rampp, 2017, Rastogi, 2014). In Ayurvedic theory, every food or medicine has its traditional properties, including Rasa (taste), Guna (effect on the digestion, fluid system and tissues in the body), Virya (effect on the metabolic thermal body), Vipaka (post-digestive effect) and Karma (action). With these traditional properties, a food / medicine can be used to balance the dosha of human body. Therefore, anything, either food or medicine, is used to sustain health based on its traditional properties, and food as medicine is also a tradition in South Asia.

3.1.3. Western opinion on food-medicine dual-use products of China

Up to now, the list for food-medicine dual-use substance of China has included 109 entities (including the pilot list), which are sourced from 151 species (Table 1). The evaluation for their importance in usages of “healthy food”, “spice” and “medicine” in Europe indicates that only 37 of the 151 species are very important in healthy food use, such as Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch., Myristica fragrans Houtt., Cannabis sativa L., Dimocarpus longan Lour., Hippophae rhamnoides L., Lycium barbarum L., Morus alba L., and so on. Additionally, 17 species are found to be used as a popular spice, and eight species are used as important medicines (excluding the medicinal use as a TCM in Europe). In the meanwhile, we find that 86 of them are not used for healthy food, 119 of them are not for spice uses, while 108 species are not used as a medicine other than TCM. These include the very commonly used species in China, such as Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce, Lilium lancifolium Thunb., Euryale ferox Salisb., Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt., etc. It is worth noting that the animal products are not accepted in the European healthy food market, or the Western traditional medicine, while this food-medicine list of China includes seven animal products.

Table 1.

A total of109 food-medicine entities (including the pilot) of China and their importance as food / spice/ medicine in the West.

| No. | Chinese (Pinyin) names | Source species | Parts used | Importance* in the West |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food | Spice | Medicine** | ||||

| 1 | dīngxiāng | Eugenia caryophyllata Thunb. | Bud | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | bājiǎohuíxiāng | Illicium verum Hook.f. | Fruit | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | dāodòu | Canavalia gladiate (Jacq.) DC. | Seed | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | xiǎohuíxiāng | Foeniculum vulgare Mill. | Fruit | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | xiǎojì | Cirsium setosum (Willd.) MB. | Aerial part | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | shānyào | Dioscorea opposita Thunb. | Root and fruit | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | shānzhā | Crataegus pinnatifida Bge. var. major N.E.Br. | Fruit | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | shānzhā | Crataegus pinnatifida Bge. | Fruit | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | mǎchǐxiàn | Portulaca oleracea L. | Aerial part | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 10 | wūméi | Prunus mume (Sieb.) Sieb. et Zucc. | Fruit | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 11 | mùguā | Chaenomeles speciosa (Sweet) Nakai | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | huǒmárén | Cannabis sativa L. | Seed | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 13 | dàidàihuā | Citrus aurantium L. var. amara Engl. | Bud and fruit | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 14 | yùzhú | Polygonatum odoratum (Mill.) Druce | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | gāncǎo | Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. | Root and rhizome | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 16 | gāncǎo | Glycyrrhiza inflata Bat. | Root and rhizome | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 17 | gāncǎo | Glycyrrhiza glabra L. | Root and rhizome | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 18 | báizhǐ | Angelica dahurica (Fisch. ex Hoffm.) Benth. et Hook.f. | Root | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 19 | báizhǐ | Angelica dahurica (Fisch. ex Hoffm.) Benth. et Hook.f. var. formosana (Boiss.) Shan et Yuan | Root | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 20 | báiguǒ | Ginkgo biloba L. | Seed | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 21 | báibiǎndòu/ báibiǎndòuhuā | Dolichos lablab L. | Seed and flower | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | lóngyǎnròu | Dimocarpus longan Lour. | Aril | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | juémíngzi | Cassia obtusifolia L. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 24 | juémíngzi | Cassia tora L. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | bǎihé | Lilium lancifolium Thunb. | Bulb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | bǎihé | Lilium brownii F.E. Brown var. viridulum Baker | Bulb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 | bǎihé | Lilium pumilum DC. | Bulb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | ròudòukòu | Myristica fragrans Houtt. | Seed | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 29 | ròuguì | Cinnamomum cassia Presl | Bark | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 30 | yúgānzǐ | Phyllanthus emblica L. | Fruit | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 31 | fóshǒu | Citrus medica L. var. sarcodactylis Swingle | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32 | kǔxìngrén | Prunus armeniaca L. var. ansu Maxim | Seed | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | kǔxìngrén | Prunus sibirica L. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 34 | kǔxìngrén | Prunus mandshurica (Maxim) Koehne | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 35 | kǔxìngrén | Prunus armeniaca L. | Seed | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 36 | tiánxìngrén | Prunus armeniaca L. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 37 | tiánxìngrén | Prunus armeniaca L. var. ansu Maxim | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 38 | shājí | Hippophae rhamnoides L. | Fruit | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 39 | qiànshí | Euryale ferox Salisb. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 40 | huājiāo | Zanthoxylum schinifoliumSieb.et Zucc. | Peel | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 41 | huājiāo | Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. | Peel | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 42 | chìxiǎodòu | Vigna umbellata Ohwi et Ohashi | Seed | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 43 | chìxiǎodòu | Vigna angularis Ohwi et Ohashi | Seed | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 44 | màiyá | Hordeum vulgare L. | Sprout | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 45 | kūnbù | Laminaria japonica Aresch. | Thallus | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 46 | kūnbù | Ecklonia kurome Okam. | Thallus | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 47 | zǎo (dàzǎo, hēizǎo) | Ziziphus jujuba Mill. | Fruit | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 48 | luóhànguǒ | Siraitia grosvenorii (Swingle.) C. Jeffrey ex A.M. Lu et Z.Y. Zhang | Fruit | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 49 | yùlǐrén | Prunus humilis Bge. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 | yùlǐrén | Prunus japonica Thunb. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 51 | yùlǐrén | Prunus pedunculata Maxim. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 52 | jīnyínhuā | Lonicera japonica Thunb. | Bud and flower | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 53 | qīngguǒ | Canarium album Raeusch. | Fruit | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 54 | yúxīngcǎo | Houttuynia cordata Thunb. | Whole plant | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 55 | jiāng | Zingiber officinale Rosc. | Rhizome | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 56 | zhǐjǔzǐ | Hovenia dulcis Thunb. | Fruit and carpopodium | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 57 | gǒuqǐzǐ | Lycium barbarum L. | Fruit | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 58 | zhīzi | Gardenia jasminoides Ellis | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 59 | shārén | Amomum villosum Lour. | Fruit | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 60 | shārén | Amomum villosum Lour. var. xanthioides T.L. Wu et Senjen | Fruit | 0 | 1 | O |

| 61 | shārén | Amomum longiligulare T.L.Wu | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 62 | pàngdàhǎi | Sterculia lychnophora Hance | Seed | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 63 | fúlíng | Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf | Sclerotium | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 64 | xiāngyuán | Citrus medica L. | Fruit | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 65 | xiāngyuán | Citrus wilsonii Tanaka | Fruit | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 66 | xiāngrú | Mosla chinensis Maxim. | Aerial part | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 67 | xiāngrú | Mosla chinensis ‘jiangxiangru’ | Aerial part | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 68 | táorén | Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | Seed | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 69 | táorén | Prunus davidiana (Carr.) Franch. | Seed | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 70 | sāngyè | Morus alba L. | Leaf | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 71 | sāngshèn | Morus alba L. | Infructescence | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 72 | júhóng | Citrus reticulata Blanco | Peel | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 73 | jiégěng | Platycodon grandiflorum (Jacq.) A. DC. | Root | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 74 | yìzhìrén | Alpinia oxyphylla Miq. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 75 | héyè | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. | Leaf | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 76 | láifúzǐ | Raphanus sativus L. | Seed | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 77 | liánzǐ | Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 78 | gāoliángjiāng | Alpinia officinarum Hance | Rhizome | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 79 | dànzhúyè | Lophatherum gracile Brongn. | Stem and leaf | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 80 | dàndòuchǐ | Glycine max (L.) Merr. | Fermented seed | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 81 | júhuā | Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. | Infructescence | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 82 | júqǔ | Cichorium glandulosumBoiss.et Huet | Whole plant | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 83 | júqǔ | Cichorium intybus L. | Whole plant | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 84 | huángjièzǐ | Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. et Coss | Seed | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 85 | huángjīng | Polygonatum kingianumColl.et Hemsl. | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 86 | huángjīng | Polygonatum sibiricum Red. | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 87 | huángjīng | Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 88 | zǐsū | Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. | Leaf | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 89 | zǐsūzǐ | Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 90 | gěgēn | Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi | Root | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 91 | gěgēn | Pueraria thomsonii Benth. | Root | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 92 | hēizhīma | Sesamum indicum L. | Seed | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 93 | hēihújiāo | Piper nigrum L. | Fruit | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 94 | huáihuā、huáimǐ | Sophora japonica L. | Flower and bud | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 95 | púgōngyīng | Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz. | Whole plant | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 96 | púgōngyīng | Taraxacum borealisinense Kitam. | Whole plant | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 97 | púgōngyīng | Taraxacum spp. | Whole plant | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 98 | fěizi | Torreya grandis Fort. | Seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 99 | suānzǎo/suānzǎorén | Ziziphus jujuba Mill. var. spinosa (Bunge) Hu ex H.F. Chou | Pulp and seed | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 100 | xiānbáimáogēn | Imperata cylindrica Beauv. var. major (nees) C.E. Hubb. | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 101 | xiānlúgēn | Phragmites communis Trin. | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 102 | júpí (huò chénpí) | Citrus reticulata Blanco | Peel | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 103 | bòhe | Mentha haplocalyx Briq. | Aerial part | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 104 | yìyǐrén | Coix lacryma-jobi L. var. mayuen (Roman.) Stapf | Seed | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 105 | xièbái | Allium macrostemon Bge. | Bulb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 106 | xièbái | Allium chinense G.Don | Bulb | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 107 | fùpénzǐ | Rubus chingii Hu | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 108 | huòxiāng | Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. | Aerial part | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 109 | huòxiāng | Agastache rugosus (Fisch. et Mey.) O. Ktze. | Aerial part | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 110 | wūshāoshé | Zaocys dhumnades (Cantor) | Body | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 111 | mǔlì | Ostrea gigas Thunberg | Shell | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 112 | mǔlì | Ostrea talienwhanensis Crosse | Shell | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 113 | mǔlì | Ostrea rivularis Gould | Shell | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 114 | ējiāo | Equus asinus L. | Skin jelly | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 115 | jīnèijīn | Gallus gallus domesticus Brisson | Gizzardskin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 116 | fēngmì | Apis cerana Fabricius | Honey | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 117 | fēngmì | Apis mellifera Linnaeus | Honey | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 118 | fùshé (qíshé) | Agkistrodon acutus (Güenther) | Body | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 119 | rénshēn | Panax ginseng C.A. Mey | Root and rhizome | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 120 | shānyínhuā | Lonicera confuse DC. | Bud and flower | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 121 | shānyínhuā | Lonicera hypoglauca Miq. | Bud and flower | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 122 | shānyínhuā | Lonicera macranthoides Hand. -Mazz. | Bud and flower | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 123 | shānyínhuā | Lonicera fulvotomentosa Hsu et S.C. Cheng | Bud and flower | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 124 | yánsuī | Coriandrum sativum L. | Fruit and seed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 125 | méiguīhuā | Rosa rugosa Thunb | Bud | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 126 | méiguīhuā | Rose rugosa cv. Plena | Bud | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 127 | sōnghuāfěn | Pinus massoniana Lamb. | Pollen | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 128 | sōnghuāfěn | Pinus tabuliformis Carr. | Pollen | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 129 | sōnghuāfěn | Pinus spp. | Pollen | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 130 | fěngé | Pueraria thomsonii Benth. | Root | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 131 | bùzhāyè | Microcos paniculata L. | Leaf | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 132 | xiàkūcǎo | Prunella vulgaris L. | Infructescence | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 133 | dāngguī | Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels. | Root | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 134 | shānnài | Kaempferia galanga L. | Rhizome | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 135 | xīhónghuā | Crocus sativus L. | Stigma | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 136 | cǎoguǒ | Amomum tsao-ko Crevost et Lemaire | Fruit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 137 | jiānghuáng | Curcuma Longa L. | Rhizome | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 138 | bìbá | Piper longum L. | Infructescense | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 139 | dǎngshēn | Codonopsis pilosula (Franch.) Nannf. L.T. Shen | Root | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 140 | dǎngshēn | Codonopsis pilosula Nannf. var. modesta (Nannf.) L.T.Shen | Root | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 141 | dǎngshēn | Codonopsis tangshen Oliv. | Root | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 142 | ròucōngróng (huāngmò) | Cistanche deserticola Y.C. Ma | Stem | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 143 | tiěpíshíhú | Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo | Stem | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 144 | xīyángshēn | Panax quinquefolium L. | Root | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 145 | huángqí | Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bge. var. mongholicus (Bge.) Hsiao | Root | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 146 | huángqí | Astragalus membranaceus (Fisch.) Bge. | Root | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 147 | língzhī | Ganoderma lucidum (Leyss. ex Fr.) Karst. | Sporophore | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 148 | língzhī | Ganoderma sinense Zhao, Xu et Zhang | Sporophore | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 149 | shānzhūyú | Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc. | Pulp | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 150 | tiānmá | Gastrodia elata Bl. | Rhizome | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 151 | dùzhòngyè | Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. | Leaf | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: * 0 means no such use, while 3 indicates a popular use; 1 and 2 are in-between. ** These are the medicinal use excluding TCM.

Accordingly, most of the Chinese food-medicine species (as a representative of the East) are still not used / accepted in the West (as represented by the Europe), suggesting the differences in the food-medicine knowledge between the East and West. For example, the very commonly used Lonicera in China is not consumed in Europe at all. In the meanwhile, some of the species are used in both sides, but the usages might differ. Such as Crataegus, which is for digestion in China while for cardiovascular in Europe, and the different usages may be attributed to their independent historical origins (Caliskan, 2015).

Moreover, we have seen knowledge of some species have transmitted (partially) directly from China to the Europe, such as goji berry and ginseng. Another example is Ginkgo, the seed of which is used in China as a traditional food-medicine, while its leaf is developed in Europe as a source of flavonoids in food supplement. In recent decades, China has adopted the ginkgo leaf as a food ingredient and drug material, but the seed is still not accepted by European market.

It is found that many China-sourced entities, which are with a plenty of scientific data on phytochemistry, pharmacology and safety, have been accepted in Europe, e.g., Lycium barbarum L., Panax ginseng C.A. Mey, and Ganoderma lucidum (Leyss. ex Fr.) Karst. Therefore, scientific evidence on safety and bioactivity should be the premise for the cross-cultural acceptance of the traditional food-medicine products.

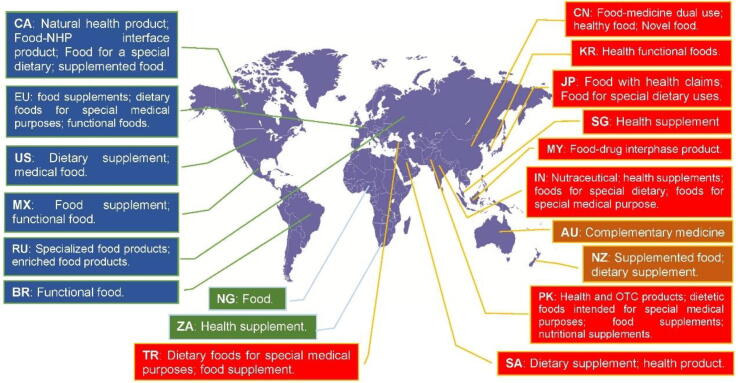

The legislative terms used for the interface of food and medicine in 20 countries / regions were compiled based on our survey (Fig. 2). The definitions of these terms are presented in supplement (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Legislative terms for the interface of food and medicine in selected countries / regions.

3.2. Current definitions of interface of food and medicine

3.2.1. China

In China, food, medicine, and their interface are formally categorized into food, healthy food, food-medicine-dual-use substance, novel food ingredients, and medicine. Food Safety Law of China plays a key role in the regulation of food related substance in China. It is worth noting that a food is not for curative purposes but can be the stuff traditionally used as both food and Chinese materia medica. The healthy food is kind of special food for specific people to regulate health but are not for curative purposes. However, a healthy food is allowed for the recognized 24 function claims once it is proven by the official functional assessments. Food-medicine-dual-use substance must be adopted in Chinese Pharmacopoeia with a food use tradition, and the National Health Commission has published an updating list for these substances. The recognition of novel food ingredients allows for using new food sources. Lastly, medicine refers to the substance for curative purposes.

Accordingly, there are intersections among these categories. For instance, a Food-Medicine-dual-use substance must be a medicine in pharmacopoeia, but only when it is not used for curative purposes it belongs to food. The ingredient of healthy food is open to the substances of food safety and with proven health benefits, while is not listed in the official forbidden list. Novel food ingredients have higher potential compatibility with others. Taking goji as an example: as a traditional food, it is adopted in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia as well as in the list of Food-Medicine-dual-use substance, in the meanwhile, it is not in the official forbidden list for healthy food. Therefore, goji can be a medicine, food-medicine-dual-use substance, and an ingredient for healthy food.

3.2.2. Japan

In Japan, food includes (a) food with health claims (FHC), (b) food for special dietary uses (FOSDU), and (c) other foods (may include so-called functional foods) (MHLW, 2022). FHC has two sub-categories: foods with nutrient function claims (FNFC) and foods for specified health uses (FOSHU). FOSDU includes five categories. In 2015, a new system was termed “foods with function claims (FFC)”, and was integrated into the FHC (Shimizu, 2019).

It can be seen that boundaries among these sub-categories are not clear. For example, FOSDU and FHC have an intersection, which is FOSHU. Moreover, the new category FFC is similar to FOSHU, and their differences are found in the application process for the health claim labeling, and some of the health claims of FFC have already been adopted in the FOSHU system (Shimizu, 2019).

3.2.3. South Korea

Health functional foods includes all the interface of food and medicine in South Korea. It is defined as “foods manufactured (including processing; hereinafter the same shall apply) with functional raw materials or ingredients beneficial to human health” (Korean National Law Information Centre, 2019).

3.2.4. Thailand

Foods in Thailand are classified into four categories based on their safety risk, namely: (a) specially controlled food, (b) standardized food, (c) food with labeling and (d) general food (Ratanakorn, 2016). The interface of food and medicine may be found in (a), (b) or (c). For example, herbal tea and food supplements are included in standardized food, and the specially purposed food such as medical food belongs to food with labeling.

3.2.5. Malaysia

In Malaysia, products with combination of food ingredients and active ingredients for oral consumption are recognized as food-drug interphase (FDI) products (Ministry of Health of Malaysia, 2021). FDI products are not clearly defined as food or drug. FDI is not a product category, and it is important to determine whether the products are regulated as drug or as food because different regulatory requirements apply.

3.2.6. Singapore

In Singapore, health supplement means a product that is used to supplement a diet with benefits beyond those of normal nutrients, and to support or maintain the healthy functions of the human body. However, it cannot be an item of a meal or diet (Singapore Food Agnecy, 2022). Products in the food Health product interface includes (a) part of a daily diet, including Chinese medicinal material commonly used in food, (b) supplementation to a diet, and (c) those used for a medicinal purpose.

3.2.7. Pakistan

In Pakistan, “Health and OTC products”, “Dietetic foods intended for special medical purposes”, “food supplements” and “nutritional supplements” are assigned (Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan, 2012, Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan, 2014). Although defined separately, these terms have overlaps of different extent, and food-medicine products may be included in any of these categories.

3.2.8. India

In India, the interface of food and medicine may fall into “nutraceutical”, “health supplements”, “foods for special dietary” or “foods for special medical purpose” (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India, 2020). Of these, only the source of “nutraceutical” is determined as naturally occurring ingredients, others are all defined based on their extra health purposes other than food.

3.2.9. Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, “dietary supplement” and “health product” are defined (Saudi Food & Drug Authority, 2020), and the food-medicine products may belong to either of them. “Dietary supplement” is not in a pharmaceutical dosage form while the latter is, but their purposes are compatible to some extent.

3.2.10. Turkey

“Dietary foods for special medical purposes” and “Food supplement” are defined in Turkey (Council of Ministers of Turkey, 2010). Besides their similarity in nutritional properties, they are both used for dietary management.

3.2.11. Australia

In Australia, products for oral consumption are regulated by the Australian government as either foods or therapeutic goods. Therapeutic goods can be represented in any form and are for therapeutic use. The interface of foods and therapeutic good is called complementary medicines, which include herbal medicines, traditional medicines, vitamins, special purpose foods, nutritional supplements, homoeopathic and naturopathic products (Legislative Council Secretariat of Australia, 2001).

3.2.12. New Zealand

In New Zealand, “supplemented food” and “dietary supplement” are applied (Minister for Food Safety of New Zealand, 2016; Ministry of Health of New Zealand, 1985). “Supplemented food” is represented as a food while the later is in controlled dosage, although there is a big overlap.

3.2.13. Russia

The food-medicine products may fall into “specialized food products” or “enriched food products” in Russia (Urazbaeva, 2018). The former is with an established ratio of composition, which are intended for safe use by certain categories of people, while the later sets a limitation for the biologically active substances content at safe level of consumption.

3.2.14. South Africa

In South Africa, “Health supplement” include stuffs for restoring, correcting or modifying any physical or mental state but not in forms of medicines (Drugs Control Council of South Africa, 1965).

3.2.15. Nigeria

The category in Nigeria is different, since the food and medicine interface products are included in food (National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control of Nigerias, 2004).

3.2.16. European Union

“Food supplement”, “dietary foods for special medical purposes” and “functional food” are defined in the EU. “Food supplements” is to supplement the normal diet with a nutritional or physiological effect, designed to be taken in measured small unit quantities (Directive 2002/46/EC). “Dietary foods for special medical purposes” are for the dietary management of patients and to be used under medical supervision. (Directive 1999/21/EC). “Functional food” are food which beneficially affects one or more target functions in the body, beyond adequate nutritional effects, in a way that is relevant to either an improved state of health and well-being and/or reduction of risk of disease (EC 1924/2006) (Duttaroy, 2019).

3.2.17. Canada

In Canada, “natural health product (NHP)”, “food-NHP interface product”, “food for a special dietary” and “supplemented food” are the intermediate (Minister of Justice of Canada, 2022). “Food-NHP interface product” means any product that is in a food format, and meets the scope of natural health product (Minister of Health of Canada, 2017). “Food for a special dietary” means a food that has been specially processed or formulated to meet the particular physical or physiological requirements (Minister of Justice of Canada, 2021). “Supplemented food” may contain added vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbal or bioactive ingredients, and may have extra physiological role other than nutrition (Food Directorate of Canada, 2016).

3.2.18. United States

“Dietary supplement” and “medical food” are defined in the US. “Dietary supplement” may contain vitamin, mineral, botanical, amino acid or the concentrate of them (US FDA, 2021). “Medical food” is for the specific dietary management and should be consumed under the supervision of a physician (Lewis, Jackson, & Bailey, 2019).

3.2.19. Mexico

In Mexico, “food supplement” and “functional food” are defined. Although both them are for health purposes, the former may be presented in a pharmaceutical form, while the later is enriched with additional nutrients (the General Health Law of Mexico; Official Mexican Standard “NOM-086-SSA1-1994”, Goods and Services).

3.2.20. Brazil

Brazilian legislation does not provide a definition of functional foods, but it is possible to claim that certain foods have functional health properties (Silveira, Vianna, & Mosegui, 2009).

3.2.21. Summary

It can be seen food and medicine continuum is a common phenomenon in the worldwide, although the legislative terms for the food-medicine entities may differ among regions. Japan has a sophisticated classification system for food-medicine, while health functional foods include all these stuff in South Korea, differently, the food-medicine is included in “food” in Nigeria. The term “food-NHP interface product” in Canada is quite similar to “FDI product” of Malaysia. In China, food-medicine-dual-use substance and healthy food have an overlap, while in Japan, FHC and FOSDU intersect. As a result, globally there are diverse legislative terms for food-medicine products, the scope of these terms may be different, as well, the boundaries among these terms are blurry.

Although food-medicine products are defined differently, basically, their common property is that they have extra healthy functions beyond their normal nutritional functions. Fortunately, we have seen that the regulations for these have emphasized their function claims. For example, healthy food in China can make health claims of 24 categories, which must be based on standard assessments. Similar regulations are found in other countries / regions, e.g., EC 1924/2006 is technically for the health claims of functional foods in the EU market. Additionally, these products are requested to register, by which a list for the approved products is published formally as a reference for market access, and this policy is effective in maintaining this high-profit market.

There are still food-medicine products whose health benefits are based on traditional uses, as the long term used in history can be a reliable proof for their safety. As a typically example, food-medicine dual-use substances of China are allowed for food consumption, although they are all medicinal materials in pharmacopoeia. To control these products, the government has published an updating list for the permitted materials, which must be evaluated by a working panel. The situation in the EU is similar, that the traditional use can be alternative evidence for the safety of traditional food (EU-efsa Panel on Dietetic Products et al., 2021).

It is worth noting that the cross-cultural communication of food-medicine products are possible based on current regulations. One of the pathways is the adoption of traditional uses. For example, many of the Chinese herbal medicines are with food use tradition, and these has already been adopted in many countries, e.g., Singapore adopts some of the Chinese medicinal materials to be used as part of a diet, which belong to the category of “health supplement”. Besides, novel food paves a pragmatical way for adopting a foreign food-medicine. In most of the regions, those exotic food products are allowed to be imported on the promise of application. For example, when a foreign food-medicine product imports to China, the technical documents of this product as well as the historical use proof in its origin country are requested. The new Novel Food Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 has declared the requirements for importing into the EU.

4. Conclusion

Food and medicine continuum is a global phenomenon. The present study traced the historical roots and the current regulations on the interface of food and medicine in both the East and West of the world. The historical root of food and medicine continuum lie in the herbal traditions of millennia, such as traditional Chinese medicine of China, Ayurveda of South Asia, Hippocratic and Galenic medicine of the West. The food-medicine knowledge in different regions is different since the biocultural diversity. Currently, food-medicine products are increasingly popular. Although the legislative terms for food-medicine products may differ among regions, the regulations are similar, which allows for their cross-cultural communication. The long-term uses are recognized as reliable proofs for the safety of these traditional foods, moreover, the studies on safety and bioactivity provide sufficient scientific evidence for their safety and functions. Besides, laws on novel food pave a pragmatic pathway for the cross-cultural exchange of the traditional food-medicine products. Finally, we recommend facilitating the cross-cultural communication of the food-medicine knowledge in the East and West, thus to make the best use of the traditional health wisdom in the globe.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The present work was supported financially by the Strategic Consulting Project of Chinese Academy of Engineering (No. 2021-X2-10) and Innovation Team and Talents Cultivation Program of National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. ZYYCXTD-D-202005). The authors would like to sincerely thank Prof. Michael Heinrich from UCL School of Pharmacy for his valuable supports in the survey and consulting activities.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chmed.2022.12.002.

Contributor Information

Chunnian He, Email: cnhe@implad.ac.cn.

Peigen Xiao, Email: pgxiao@implad.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Adelman J., Haushofer L. Introduction: Food as medicine, medicine as food. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 2018;73(2):127–134. doi: 10.1093/jhmas/jry010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliskan O. In: The mediterranean diet. Preedy V.R., Watson R.R., editors. Academic Press; Elsevier: 2015. Mediterranean hawthorn fruit (Crataegus) species and potential usage; pp. 621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Chen N. Columbia University Press; New York: 2008. Food, medicine, and the quest for good health. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Ministers of Turkey . Plant Health; Food and Feed: 2010. Law on veterinary services. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (2012). Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan Act.

- Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan (2014). Alternative Medicines and Health Products (Enlistment) Rules.

- Drugs Control Council of South Africa (1965). Drugs Control Act.

- Duttaroy A.K. In: Nutraceutical and functional food regulations in the united states and around the world. third ed. Bagchi D., editor. Academic Press; UK and US: 2019. Regulation of functional foods in European Union: Assessment of health claim by the European Food Safety Authority; pp. 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin N.L., Ross P.J. Food as medicine and medicine as food: An adaptive framework for the interpretation of plant utilization among the Hausa of northern Nigeria. Social Science & Medicine. 1982;16(17):1559–1573. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EU-efsa Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies, Turck, D., Bresson, J. L., Burlingame, B., Dean, ... van Loveren, H. (2021). Guidance on the preparation and submission of the notification and application for authorisation of traditional foods from third countries in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 (Revision 1). EFSA Journal, 19(3), e06557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Food Directorate of Canada (2016). Category Specific Guidance for Temporary Marketing Authorization: Supplemented Food.

- Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (2020). Guidance Note on Food for Special Medical Purposes.

- Grant M. Routledge; London and New York: 2002. Galen on food and diet. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M., Kum K.Y., Yao R. In: Routledge handbook of Chinese Medicine. Lo V., Stanley-Baker M., editors. Routledge; London: 2022. Decontextualized Chinese Medicines – Their uses as health foods and medicines in the ‘global West’; pp. 721–741. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich M., Yao R., Xiao P. ‘Food and medicine continuum’ – why we should promote cross-cultural communication between the global East and West. Chinese Herbal Medicines. 2022;14(1):3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.chmed.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korean National Law Information Centre (2019). Statutes of the Republic of Korea.

- Kumar S., Dobos G.J., Rampp T. The significance of ayurvedic medicinal plants. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;22(3):494–501. doi: 10.1177/2156587216671392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Council Secretariat of Australia (2001). Regulation of Health Food in Australia.

- Leonti M. The co-evolutionary perspective of the food-medicine continuum and wild gathered and cultivated vegetables. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2012;59(7):1295–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C.A., Jackson M.C., Bailey J.R. Nutraceutical and functional food regulations in the united states and around the world. Academic Press; UK and US: 2019. Understanding medical foods under FDA regulations; pp. 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Wei, X., Qin, Z., & Xiao, P. (2015). Annotation of drug and food are the same origin and its realistic significance. Modern Chinese Medicine, 17(12), 1250–1252, 1279.

- Meng, S. (725). Meng, S., Zhang, D., & Xie, H. (1984). Shi Liao Ben Cao. Beijing: People’s Health Press.

- MHLW (2022). Food with Health Claims, Food for Special Dietary Uses, and Nutrition Labeling. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/topics/foodsafety/fhc/. (Accessed 17-10-2022).

- Minister for Food Safety of New Zealand (2016). New Zealand Food (Supplemented Food) Standard.

- Minister of Health of Canada (2017). Classification of Products at the Food-natural Health Product Interface: Products in Food Formats.

- Minister of Justice of Canada (2021). Food and Drugs Act.

- Minister of Justice of Canada (2022). Natural Health Products Regulations.

- Ministry of Health of Malaysia (2021). Drug Registration Guidance Document (DRGD).

- National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control of Nigerias (2004). National Agency For Food And Drug Administration And Control Act.

- Rastogi S. Springer; New York: 2014. Ayurvedic science of food and nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Ratanakorn, S. (2016). Food Regulations and Enforcement in Thailand, Reference Module in Food Science.

- Saudi Food & Drug Authority (2020). Saudi FDA Products Classification Guidance.

- Shimizu M. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the United States and around the World. UK and US: Academic Press; 2019. History and current status of functional food regulations in Japan; pp. 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira T., Vianna C., Mosegui G. Brazilian legislation for functional foods and the interface with the legislation for other food and medicine classes: Contradictions and omissions. Physis. 2009;19(4):1189–1202. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Food Agency (2022). General Classification of Health and Food Products.

- Sun, S. M. (652). Sun, S. M., & Liu, Q. (1998). Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang. Beijing: China TCM Press.

- Totelin L. When foods become remedies in ancient Greece: The curious case of garlic and other substances. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;167:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totelin L. Hippocratic corpus. Oxford Classical Dictionary. 2021 doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.9780199381013.9780199388525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touwaide A., Appetiti E. Food and medicines in the Mediterranean tradition. A systematic analysis of the earliest extant body of textual evidence. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;167:11–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urazbaeva A.N. And food safety technical regulation. Wageningen University; 2018. Russian food law: Legal systems of the Russian federation and the Eurasian economic union (EAEU) [Google Scholar]

- US FDA (2021). Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

- Yao R., Heinrich M., Weckerle C.S. The genus Lycium as food and medicine: A botanical, ethnobotanical and historical review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2018;212:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.