Abstract

Background:

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are linked to substance use (SU) and substance use disorders (SUD). However, this relationship has yet to be tested among justice-involved children (JIC), and it is unclear if racial/ethnic differences exist. This study aimed to determine: (1) whether ACEs are associated with increased risk of SU and SUD among JIC; and (2) if the effects of ACEs on SU and SUD are moderated by race/ethnicity.

Methods:

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to examine a statewide dataset of 79,960 JIC from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. Marginal odds were estimated to examine how race moderates the relationship between ACEs and SU and SUD.

Results:

Results showed higher ACEs scores were linked to SU and SUD. Black JIC were 2.46 times more likely, and Latinx JIC were 1.40 times more likely to report SU than white JIC. Specifically, Black and Latinx JIC with a higher average ACEs score were more likely to report SU but less likely to have ever been diagnosed with a SUD when compared to white JIC with equivalent ACEs.

Conclusions:

Study results highlight the need to develop trauma-informed and culturally appropriate interventions for SU and SUD among JIC.

Keywords: Juvenile justice, substance use, substance use disorder, adverse childhood experiences, race

Introduction

Substance use (SU) among adolescents can have a deleterious effect on their health and wellbeing. Adolescence is an important time to understand SU because individuals who initiate use before age 18 are more likely to develop a substance use disorder (SUD) in adulthood (McCabe et al., 2007). Exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) is an important predisposing factor for both SU (Carliner et al., 2016; Scheidell et al., 2018) and SUD (Carliner et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2006), but there is evidence that the impact of ACEs on SU outcomes may vary across racial/ethnic lines (Johnson, 2017a; Rich & Grey, 2005). Understanding how race/ethnicity may moderate the relationship between ACEs and SU and SUD among adolescents is a critical step toward developing culturally tailored interventions and reducing health disparities.

Justice-involved children and adolescents (JIC) represent a high-risk population for SU. Studies have found that up to 80% of JIC—minors who are arrested and/or processed by the juvenile justice system—indicate lifetime SU (Aalsma et al., 2019). The risk of developing a SUD among JIC is high, with research indicating that at least 33% of JIC meet diagnostic criteria (Wasserman et al., 2010). This rate is almost six times greater than rates of adolescents with no juvenile justice involvement (Knight et al., 2019). Many adolescents in need of behavioral health services first access them through the juvenile justice system (Johnson & Tran, 2020). However, despite research indicating that SUD treatment in custody and after release can decrease recidivism, many JIC are left untreated. This is particularly true for racially/ethnically minoritized populations. A study examining racial/ethnic differences of JIC SU and services received found that Black and Latinx JIC were more likely to be in confinement with no access to substance-related services or were in residential placement with no substance-related services available (Heaton, 2018). This shows the systemic disadvantage among racially/ethnically minoritized youth in the juvenile justice system can lead to limited access to treatment services.

For JIC, racial/ethnic disparities occur at several points in the juvenile justice system, especially in the diagnosis of SUD and receiving treatment. A systematic review by Spinney et al. (2016) found approximately 69% of the studies that met the inclusion criteria for the review indicated race can affect clinicians’ decision to refer JIC to addiction services. In a study focused on data from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ), Elliott et al. (2018) identified racial/ethnic disparities in referrals to SUD assessments, with Black and Latinx JIC being less likely to have been referred to SUD assessments than white JIC. This disparity may be the result of implicit bias among physicians or community actors that conduct diagnostic screening, thus resulting in racially minoritized JIC being underdiagnosed and undertreated (Hall et al., 2015; Heaton, 2018; Johnson & Tran, 2020).

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

JIC represent a population of youth in the US who have experienced a significant amount of ACEs. The most prevalent and widely researched types of ACEs include emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, domestic violence, household SU, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, and household member incarceration (Baglivio et al., 2014; Felitti et al., 1998; Rogers et al., 2021). Recent studies found that over 90% of JIC in the US experienced one or more types of ACEs (Baglivio et al., 2014; Johnson, 2017a), and up to 30% of JIC meet the clinical criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) according to the DSM-IV-TR (Dierkhising et al., 2013). SU is a common coping mechanism for managing exposure to ACEs (Merrick et al., 2020), which is why it is critical to examine the relationship between exposure to ACEs and SU among JIC.

ACEs and SU and SUD

Research indicates that ACEs are associated with a higher likelihood of SU (Ding et al., 2014; Dube et al., 2003; Johnson et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2018) and SUD (Bender et al., 2015; LeTendre & Reed, 2017). Johnson et al. (2010) found that, among out-of-treatment Black women who used substances, those with lifetime comorbid alcohol and cocaine dependence reported significantly more ACEs and had a higher prevalence of lifetime diagnosis of PTSD and PTSD-related symptoms than non-dependent women. Chen et al. (2011) found that neglected children were at greater risk of being arrested for later juvenile drug and alcohol offenses than non-neglected children. Smith and Saldana (2013) found that childhood sexual abuse was significantly related to justice-involved girls’ SU during adolescence. Rogers et al. (2021) examined the longitudinal effects of ACEs across adolescence and into early adulthood among Latinx populations. The research showed Latinx populations have an increased risk for negative consequences associated with SU (e.g., poorer treatment utilization and outcomes), and Latinx adolescents with ACEs can start high school with higher reported levels of SU. The study indicated that this disparity could persist long-term, demonstrating that ACEs may be linked to higher rates of and continued SU over time (Rogers et al., 2021). Research has also indicated that factors such as neighborhood characteristics, poverty, and school enrollment status have been associated with justice involvement and recidivism (Campbell et al., 2020) and may put adolescents at higher risk for experiencing ACEs and SU (Wolff et al., 2018). In addition, JIC who experience ACEs may also be at higher risk for mental health problems in addition to SU (Shin et al., 2018). For example, ACEs is one of the most common predictors of suicidal ideation and attempt among JIC (Johnson, 2017b). These studies highlight the strong link between ACEs and risk of SU and SUD.

A scoping systematic review examining ACEs among JIC reported mixed findings of the relationship between ACEs, SU, and related problems (Folk et al., 2021). For example, some of the studies included in the review indicated that ACEs were significantly linked to SU. Other studies examining risk and protective factors and ACEs exposure among JIC found that depending on the group (e.g., low need vs. high need or male vs. female), ACEs exposure did not guarantee an elevated risk for SU (Lee & Taxman, 2020; Logan-Greene et al., 2020). This research highlights the nuances of ACEs and risk assessment of JIC and the need for multidimensional, trauma-informed interventions to address the individual needs of youth in the justice system (Lee & Taxman, 2020).

ACEs and race

Racially/ethnically minoritized communities tend to have less access to protective resources that may buffer the impact of ACEs and are also exposed to more social disadvantages that could exacerbate the effects of ACEs (Wilson, 2012). The mass incarceration of racially/ethnically minoritized males diminishes many family and community-level resources by systematically removing minoritized fathers, sons, uncles, and companions while simultaneously exposing racially/ethnically minoritized families to the trauma of losing a household member or companion to incarceration (Alexander, 2010). Black and Latinx communities are disproportionately affected by mass incarceration, the criminalization of behavioral health issues, the school-to-prison pipeline, disparities in the criminal justice system, and other social inequalities (Kakade et al., 2012). The double stigma of being a racially/ethnically minoritized and a JIC may amplify barriers to behavioral health resources that can prevent or treat SU and SUD. Furthermore, the collateral consequences of justice involvement—revoked access to opportunities for employment, education, and social inclusion—can often be harsher for racially/ethnically minoritized children and communities (Love et al., 2016). All of these factors can exacerbate the impact of ACEs and SU for individuals who are racially/ethnically minoritized. Understanding how race and ACEs are associated with SU and SUD among this unique population is essential for developing prevention and treatment efforts designed to prevent adverse impacts of ACEs and SU on JIC (Wyrick & Atkinson, 2021).

Current study

Past research has been conducted to assess the relationship between ACEs and SU and SUD among justice-involved populations. However, these studies do not directly assess how race/ethnicity can moderate the relationships between ACEs and SU and SUD. Therefore, the current study aimed to determine: (1) whether ACEs are significantly associated with a higher likelihood of SU and SUD among JIC; and (2) if the effects of ACEs on SU and SUD are moderated by race/ethnicity. SU and SUD are explored separately to examine potential disparities between those at risk for SU and those who are diagnosed with a SUD.

Drawing on empirical evidence, this study hypothesizes that experiencing ACEs will increase the risk of SU and SUD (among those who used substances and were assessed for SUD), and racially/ethnically minoritized JIC will have a higher likelihood of SU and SUD (once exposed to ACEs). Although SU and SUD may be more prevalent among white youth in the general population, this study hypothesizes racially/ethnically minoritized JIC will have a higher likelihood of SU and SUD due to the systemic disadvantage that racially/ethnically minoritized individuals face in the justice system, including issues with screening, assessments, referrals, and access to services. To test these hypotheses, the study utilized statewide data from the FLDJJ—the third-largest juvenile justice sample in the US. Demographic and psychosocial variables that have been previously linked to adolescent SU were included in our analysis as controls. This study is the first to examine the moderating role that race/ethnicity might play in the association between ACEs and SU and SUD risk among JIC. This research is also unique in its focus on JIC, a high-risk population for both SU, SUD, and ACEs.

Methods

Data

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida and the FLDJJ. Since 2004, FLDJJ has collected data on all youth who are arrested using a comprehensive assessment and case management process. When a minor is arrested in Florida, they complete an enrollment process to enter the FLDJJ system, including the administration of the Positive Achievement Change Tool (PACT) assessment. The PACT is a psychometrically validated instrument for assessing the risk/needs of juveniles in the justice system (see Baglivio & Jackowski, 2013). Trained personnel conduct PACT semi-structured interviews that assess the risk to re-offend and criminogenic need domains, including criminal history, school, free time, employment, relationships, family, SU, mental health, anti-social attitudes, aggression, and social skills. PACT interviews were conducted at FLDJJ intake centers. The total FLDJJ dataset included 80,441 JIC. However, 481 cases (<1%) were omitted due to missing SU data, resulting in a final dataset of 79,960 individuals.

Sample

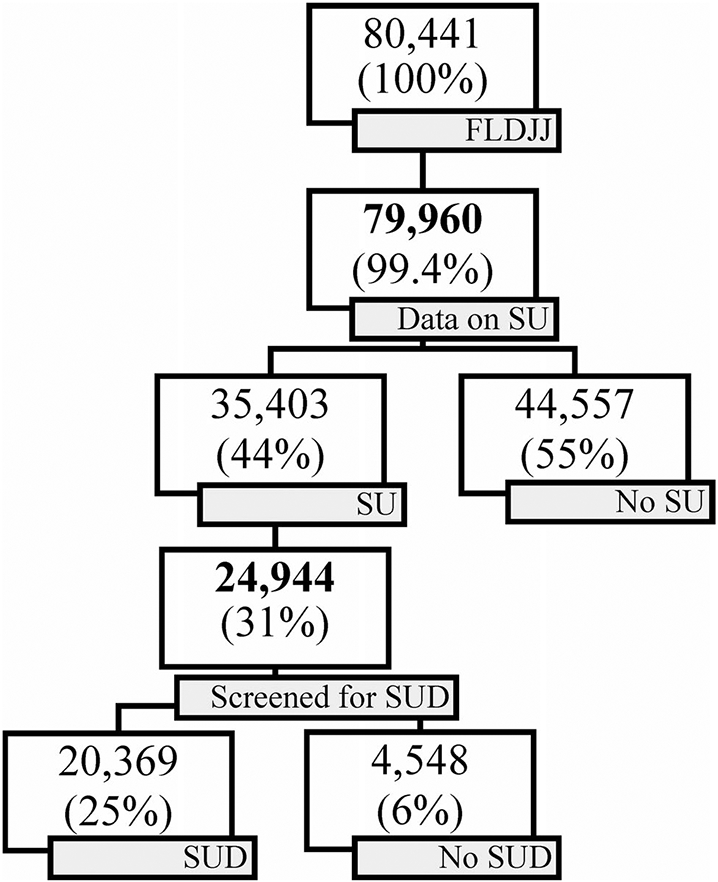

The sample of 79,960 represents all youth who entered the FLDJJ from 2004 to 2015, completed the Full PACT assessment, reached the age of 18 by 2015, and had available SU data. Nearly 38.3% were non-Latinx white (n = 30,591), 45.6% were non-Latinx Black (n = 36,443), 15.7% were Latinx (n = 12,536), and 0.5% were another race (n = 390). Roughly 21.9% of the sample were female (n = 17,497), and the mode age between 2004–2015 was 13–14. All JIC were under the age of 18 when they entered the FLDJJ. Approximately 68.4% (n = 54,116) of the 79,960 JIC were either never referred for a SUD diagnosis or were referred but never diagnosed, and therefore, were omitted from the SUD models. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of the sample.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of FLDJJ data on SU and SUD. Note. <1% (n = 481) of 80,441 individuals were omitted from the study due to missing data on SU. 29.5% (n = 10,459) of current SU (n = 35,403) were not screened for SUD and therefore omitted in the SUD models.

Measures

SU and SUD

Current SU refers to using non-prescription drugs (including marijuana) and/or alcohol within the past 30-days. SU was operationalized via a dichotomous measure that asked the participants, “have you used any illegal or non-prescription drugs or alcohol in the past 30-days?” The response items were (0) “yes” or (1) “no.” Data were self-reported.

The construct of lifetime SUD refers to being assessed and diagnosed with a SUD by a licensed professional at any time between birth and assessment year 2015 (DSM-IV was used until 2013, then DSM-5 was implemented). SUD was operationalized via a dichotomous measure that reported the results of the SUD assessment, which included history of referrals for drug/alcohol assessment for JIC. The response options were (0) assessed and diagnosed as not having a SUD or drug problem, or (1) assessed and diagnosed with a SUD. Data on the SUD measure were clinically verified by a licensed professional. Only persons who reported using drugs were assessed for SUD and included in the SUD models. This reduced the sample size in the models estimating SUD. The type of substance and current problems associated with SU were also included in the SUD model.

Adverse childhood experiences

ACEs were operationalized via a ratio-level index adopted from the ACEs score (Baglivio et al., 2014). It contained a set of 11 dichotomous variables representing 11 types of ACEs: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, physical neglect, family violence, household SU, household mental illness, parental separation or divorce, household member incarceration, and community violence. Response values were coded as (0) no, this did not occur, or (1) yes, this experience occurred. The ACEs items were summed to create a cumulative index ranging from 0 (no types of ACEs) to 11 (11 types of ACEs). Each ACE counted as one. In the interaction analysis, an ACEs score of 5 (index = 5) was used to compare Black and Latinx JIC to the reference category (white). In the literature related to ACEs, it indicates a threshold of 5 or more ACEs is associated with physical and behavioral health problems (Dube et al., 2003; Vervoort-Schel et al., 2018).

Race

Race is a social construct that often includes or is used synonymously with ethnicity and national origin (Harawa & Ford, 2009). Therefore, race was used to refer to race and ethnicity. Race was operationalized via a four-item nominal measure (0= white, 1= Black, 2= Latinx, 3= other). This variable was used to create three dummy variables, Black, Latinx, and other, with white serving as the reference category, coded as 0. The dummy variables were created using Stata “I” commands. The category labeled as other includes Native American, Asian, and unspecified JIC.

Control variables

The study adjusts for known correlates of current SU (sex, family income, history of mental problems, number of adjudicated felonies, school enrollment status, and county of residence) and lifetime SUD (sex, family income, type of substance used, reporting current SU-related problems to FLDJJ, history of mental problems, number of adjudicated felonies, school enrollment status, and county of residence). Controlling for the reporting of current SU-related problems assisted in differentiating between JIC who have problems with school, family, and behavior as a result of SU and those who use substances but do not present with any specific problems. Sex was operationalized by a self-reported “sex at birth" dichotomous measure (0= male, 1= female). Family income was measured via a four-item ordinal variable reporting the combined annual income of the JIC and family. Response options were (0) under $15,000, (1) from $15,000 to $34,999, (2) from $35,000 to $49,999, and (3) $50,000 and above.

Types of substances currently used were measured via a categorical variable recording the types of substances JIC reported using within the past 30-days. The response options were (0) marijuana only, (1) alcohol only, (2) alcohol and marijuana only, (3) illicit drugs, (4) other drugs. Response option (3) illicit drugs included: amphetamines, cocaine/crack, heroin and other opioids, inhalants, tranquilizers, and hallucinogens. Response option (4) other drugs represented JIA who disclosed a substance type that was not listed on the PACT assessment. Current SU-related problems were measured via a dichotomous variable that reports JIC current problems related to drug and alcohol use experienced within the past 30-days. The response options were (0) none, no current problems related to drug and alcohol use, including current users who did not experience problems and past users who did not have current problems, and (1) yes, current problems related to substance misuse. The (1) yes response included those who reported that drug and/or alcohol disrupted school, caused family conflict, and/or led to behavior issues.

History of mental health diagnosis was measured via a dichotomous variable reporting JIC lifetime history of any mental health diagnosis (0 no; 1 yes). Adjudicated felonies were measured via an ordinal variable reporting the actual number of JIC felony adjudications in the FLDJJ system. The categories were (0) none, (1) one, (2) two, or (3) three or more. The construct current school enrollment status referred to JIC current high school enrollment status. It was operationalized via a four-item categorical variable reporting enrollment status at intake. Response options were (0) enrolled or graduated, (1) suspended, (2) dropped out, or (3) expelled.

Analytical procedures

Data analysis was conducted using STATA, version 17 SE. Complete case analysis was appropriate given that there was minimal missing data (<1%) Missing Completely At Random (MCAR), and the sample size was large. Little’s Missing Completely At Random test was conducted, and was not significant, indicating that the data are MCAR. Demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. A chi-square test of independence was performed to compare whether there was a significant association between categorical variables and SU and SUD. An independent t-test was conducted to compare the means of the interval variables (ACEs) between non-SU versus SU and between SU without SUD versus SU with SUD. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals for SU and SUD. The covariates of sex, family income, type of substance used, current SU-related problems, history of mental health diagnosis, number of adjudicated felonies, school enrollment status, and county of residence were considered in the relevant model (type of substance used and current SU-related problems were included in the SUD model). To examine interaction effects, predicted probability and predictive marginal log odds were estimated (using the STATA margins procedures) in order to estimate and plot the interaction effects of ACEs and race and SU and SUD. To examine moderation, aORs were calculated manually. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to confirm adequate model fit.

Results

In the total sample with data on SU (79,960), 44.3% (35,403) reported current SU (past 30-days). Approximately 28.7% of those who reported current SU were white, 56.7% were Black, and 14.3% were Latinx. Among those who reported current SU and who were assessed for SUD, 81.8% (20,396) were diagnosed with a SUD. Approximately 50.1% of JIC with a SUD were white, 34.5% were Black, and 14.9% were Latinx. Among those who were assessed but diagnosed as non-SUD, 42.3% were white, 43.0% were Black, and 14.2% were Latinx. The other race category was omitted from the analyses due to a small amount of JIC identifying as Native American, Asian, or were unspecified (<5%).

In the total sample, 97.2% (77,722) reported experiencing one or more types of ACEs. The overall mean number of ACEs was 4.34. White JIC, on average, reported similar amounts of ACEs (mean = 4.56) as Black (mean = 4.36) and Latinx JIC (mean = 3.81). An average of 4.70/11 ACEs were reported among JIC who reported current SU versus 4.05/11 reported among those who did not report SU. JIC who were diagnosed with a SUD reported an average of 5.04/11 ACEs versus 4.57/11 for those without a SUD. For complete descriptive statistics, bivariate analyses, and correlation matrices for all variables included in the SU and SUD models separately see Tables 1-4.

Table 1.

Characteristics of justice-involved children by their reported past six-month substance use history.

| Overall (n = 79,960) | No current SU (n = 44,557) | Current SU (n = 35,403) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | P | |

| ACEs+ mean(SD) | 4.34(2.13) | 4.05(2.16) | 4.70(2.04) | <.000 | |||

| Race | <.000 | ||||||

| White | 30,591 | 38.3 | 20,440 | 45.9 | 10,151 | 28.7 | |

| Black | 36,443 | 45.6 | 16,365 | 36.7 | 20,078 | 56.7 | |

| Latinx | 12,536 | 15.7 | 7,481 | 16.8 | 5,055 | 14.3 | |

| Other | 390 | 0.5 | 271 | 0.6 | 119 | 0.3 | |

| Sex | <.000 | ||||||

| Male | 62,463 | 78.1 | 33,448 | 75.1 | 29,015 | 82.0 | |

| Female | 17,497 | 21.9 | 11,109 | 24.9 | 6,388 | 18.0 | |

| Income | <.000 | ||||||

| Under $15k | 20,715 | 25.9 | 10,323 | 23.2 | 10,392 | 29.4 | |

| From $15k to $34,999 | 41,883 | 52.4 | 22,853 | 51.3 | 19,030 | 53.8 | |

| From $35k to $49,999 | 11,842 | 14.8 | 7,539 | 16.9 | 4,303 | 12.2 | |

| $50k & over | 5,520 | 6.9 | 3,842 | 8.6 | 1,678 | 4.7 | |

| Past mental problems | <.000 | ||||||

| None | 66,469 | 83.1 | 38,100 | 85.5 | 28,369 | 80.1 | |

| Yes | 13,491 | 16.9 | 6,457 | 14.5 | 7,034 | 19.9 | |

| Felonies | <.000 | ||||||

| None | 24,175 | 30.2 | 18,452 | 41.4 | 5,723 | 16.2 | |

| One | 34,009 | 42.5 | 17,201 | 38.6 | 16,808 | 47.5 | |

| Two | 13,793 | 17.2 | 5,771 | 13 | 8,022 | 22.7 | |

| Three or more | 7,983 | 10.0 | 3,133 | 7 | 4,850 | 13.7 | |

| HS enrollment status | <.000 | ||||||

| Enrolled or graduate | 41,069 | 51.4 | 24,954 | 56 | 16,115 | 45.5 | |

| Suspended | 4,813 | 6.0 | 2,224 | 5 | 2,589 | 7.3 | |

| Dropped out | 26,018 | 32.5 | 13,780 | 30.9 | 12,238 | 34.6 | |

| Expelled | 8,060 | 10.1 | 3,599 | 8.1 | 4,461 | 12.6 | |

Note. Data displayed as column percent.

Symbol “+” signifies an interval variable, and the mean is reported with the standard deviations (SD) in parentheses.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation matrix for Model 2.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Substance use | – | |||||||||

| 2. ACEs | 0.08*** | – | ||||||||

| 3. Race | −0.05*** | −0.11*** | – | |||||||

| 4. Female | −0.04*** | 0.22*** | −0.11*** | – | ||||||

| 5. Income | 0.01* | −0.21*** | −0.19*** | −0.01 | – | |||||

| 6. Substance type | 0.29*** | 0.21*** | −0.14*** | 0.04*** | 0.03*** | – | ||||

| 7. SU problem | 0.18*** | 0.06*** | −0.09*** | 0.01* | 0.07*** | 0.42*** | – | |||

| 8. Mental problems | 0.02*** | 0.22*** | −0.14*** | 0.13*** | −0.00 | 0.08*** | 0.05*** | – | ||

| 9. Felonies | 0.00 | −0.03*** | 0.08*** | −0.21*** | −0.07*** | −0.04*** | −0.04*** | −0.02*** | – | |

| 10. School enrollment | 0.10*** | 0.19*** | 0.05*** | −0.01*** | −0.13*** | 0.18*** | 0.06*** | 0.03*** | 0.07*** |

Note: These data present Spearman’s correlation coefficients for all variables in Model 2.

p < 0.5

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

ACEs, race, and current SU

Model 1 in Table 5 shows the results of the logistic regression, including the association between ACEs and race on current SU. After controlling for known correlates of current SU in this population, JIC with a greater number of ACEs were more likely to report current SU. More specifically, JIC with higher average ACEs scores were 1.16 times more likely to report current SU (aOR: 1.16; 95% CI, 1.15–1.17). Black and Latinx JIC were significantly more likely to report current SU than white JIC. Specifically, Black JIC were 2.46 times more likely (aOR: 2.46; 95% CI, 2.37–2.55) and Latinx JIC were 1.40 times more likely to report current SU (aOR: 1.40; 95% CI, 1.33–1.47) when compared to white JIC.

Table 5.

Logistic regression estimating current substance use.

| Model 1: SU | ||

|---|---|---|

| aOR | CI | |

| ACE index | 1.16*** | [1.15,1.17] |

| Race (ref = White) | ||

| Black | 2.46*** | [2.37,2.55] |

| Latinx | 1.40*** | [1.33,1.47] |

| Control variables | ||

| Female (ref = Male) | 0.77*** | [0.74,0.80] |

| Family income (ref = Under $15k) | 0.94*** | [0.92,0.96] |

| $15k to $34,999 | 0.98 | [0.95,1.02] |

| $35k to $49,999 | 0.88*** | [0.83,0.93] |

| $50k and over | 0.85*** | [0.79,0.91] |

| Past mental problems (ref = None) | 1.55*** | [1.48,1.62] |

| Felonies (ref = None) | ||

| One | 3.29*** | [3.17,3.42] |

| Two | 4.20*** | [4.00,4.40] |

| Three or more | 4.50*** | [4.24,4.77] |

| HS enrollment (ref = Enrolled/Graduate) | ||

| Suspended | 1.42*** | [1.33,1.51] |

| Dropped out | 1.08*** | [1.05,1.12] |

| Expelled | 1.37*** | [1.30,1.44] |

| Constant | 0.34*** | [0.28,0.40] |

| Observations | 79960 | |

Note. 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

ACEs, race, and SUD

Model 2 in Table 6 shows the results of the logistic regression, including the main effects of ACEs and race on the likelihood of being diagnosed with a SUD conditioned on SU and assessment for SUD. After controlling for known correlates of SUD in this population, results showed higher ACEs scores were associated with a higher likelihood of SUD. On average, JIC with higher ACEs scores were 1.10 times more likely to be diagnosed with a SUD (aOR: 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08–1.12). Black JIC were 1.29 times less likely to be diagnosed with a SUD than white JIC (aOR: 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65–0.77). There was no significant difference between Latinx and white JIC.

Table 6.

Logistic regression estimating lifetime substance use disorder.

| Model 2: SUD | ||

|---|---|---|

| aOR | CI | |

| ACE Index | 1.10*** | [1.08,1.12] |

| Race (ref = White) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| Black | 0.71*** | [0.65,0.77] |

| Latinx | 0.90 | [0.80,1.01] |

| Control variables | ||

| Female (ref = Male) | 0.66*** | [0.60,0.72] |

| Family income (ref = Under $15k) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| From $15k to $34,999 | 1.11* | [1.02,1.21] |

| From $35k to $49,999 | 1.14* | [1.01,1.27] |

| $50k & over | 1.23** | [1.06,1.42] |

| Felonies (ref = None) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| One | 0.97 | [0.89,1.05] |

| Two | 1.01 | [0.91,1.12] |

| Three or more | 1.05 | [0.93,1.19] |

| Substance Type (ref = Marijuana Only) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| Alcohol only | 0.47*** | [0.38,0.58] |

| Alcohol and marijuana only | 0.98 | [0.85,1.12] |

| Illicit drug | 2.06*** | [1.73,2.46] |

| Other drugs | 0.42*** | [0.38,0.47] |

| Current SU-related problems (ref = None) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| Yes | 1.51*** | [1.34,1.69] |

| History of mental problems (ref = None) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| Yes | 0.95 | [0.87,1.04] |

| HS enrollment status (ref = Enrolled/graduate) | 1.00 | [1.00,1.00] |

| Suspended | 1.00 | [0.87,1.14] |

| Dropped out | 1.46*** | [1.35,1.58] |

| Expelled | 1.48*** | [1.31,1.66] |

| Observations | 24930 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.10 | |

Note. 95% confidence intervals in brackets. Stata omitted 14 cases in the multivariate logistic regression model reducing the sample size to 24,930. HS = high school enrollment status at the time of assessment.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Interaction effects

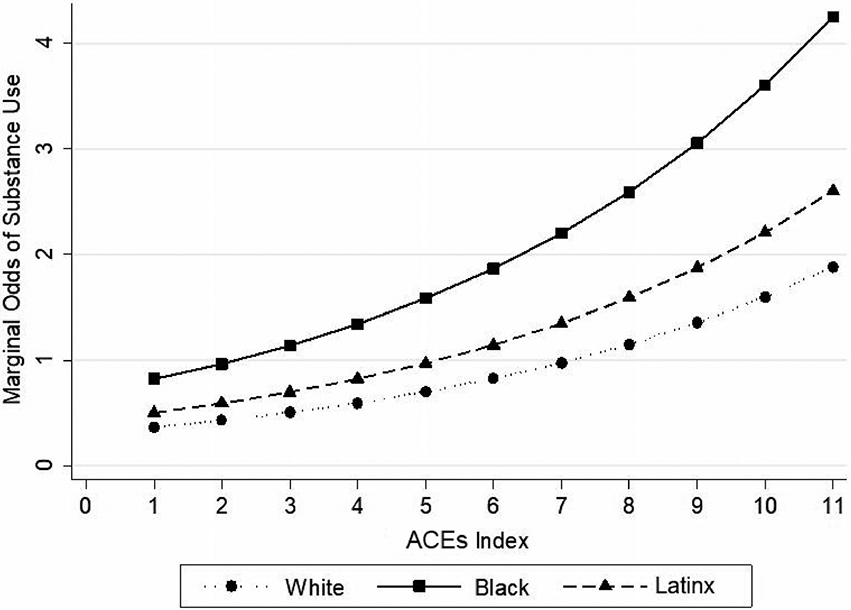

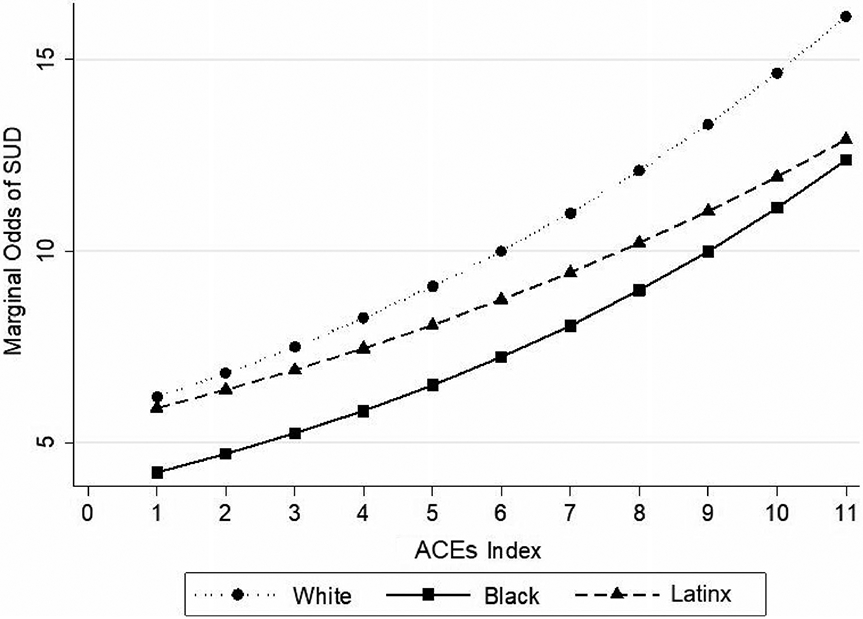

Models 3 and 4 in Table 7 show the results of the interaction effects. In Model 1, race significantly moderated the effect of ACEs on current SU. As illustrated by Figure 2, Black and Latinx JIC with higher average ACEs scores were more likely to report current SU when compared to white JIC with equivalent ACE scores. Black JIC with an ACE index of 5 were 2.5 times more likely to report current SU than white JIC with an ACE index of 5 (aOR: 2.49). Latinx JIC with an ACE index of 5 were 1.4 times more likely to report current SU than white JIC with an ACE index of 5 (aOR: 1.44). However, Model 4 in Table 7 shows that Black JIC with an ACE index of 5 had a 24% decreased chance of SUD when compared to white JIC with an ACE index of 5 (aOR: 0.76). Latinx JIC with an ACE index of 5 had an 8% decreased chance of SUD compared to white JIC with an ACE index of 5 (aOR: 0.92). See Figure 3 for an illustration.

Table 7.

Estimating the interaction effects of ACEs and race on substance use and substance use disorder (ACE index= 5).

| Model 3: SU (n = 79,960) | Model 4: SUD (n = 24,944) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrP | CI | MO | OR | PrP | CI | MO | OR | |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 0.39 | [0.38, 0.40] | 0.63 | Ref | .87 | [0.86, 0.88] | 6.62 | Ref |

| Black | 0.61 | [0.60, 0.63] | 1.57 | 2.49*** | .83 | [0.82, 0.85] | 5.03 | 0.76*** |

| Latinx | 0.48 | [0.46, 0.49] | 0.91 | 1.44*** | .86 | [0.82, 0.93] | 6.11 | 0.92*** |

Note. 95% confidence intervals in brackets. PrP = predicted probability, CI = confidence interval for PrP, MO = marginal odds, OR = odds ratio, and Ref = reference category. Data estimated using the Stata “margins” command.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Predicted marginal odds of current substance use by ACEs index and race. Note. n= 79,960.

Figure 3.

Predicted marginal odds of substance use disorder (SUD) by ACEs index and race among users screened for SUD. Note. n= 24,944.

Discussion

JIC who were screened for and diagnosed with a SUD reported an average of five ACEs—compared to an average of two among participants in the original ACEs study (Dube et al., 2003). Over 40% of the sample reported using substances in the past 30-days, and over 80% of those who were screened for SUD were diagnosed with a SUD. Experiencing more ACEs was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of SU and being diagnosed with a SUD, which aligns with prior research (Brown & Shillington, 2017; Ding et al., 2014; Dube et al., 2003; Larkin et al., 2017; Logan-Greene et al., 2020; Shin et al., 2018). These findings indicate that a trauma-informed approach may be helpful in the prevention and treatment of SUD among JIC to address SUD and ACEs simultaneously. Black JIC were more likely to use substances compared to white JIC, and the association between ACEs and SU was higher for Black and Latinx JIC compared to white JIC. These findings also align with prior research (Chen et al., 2011; Folk et al., 2021; Smith & Saldana, 2013). Understanding these synergistic effects of ACEs and race can help understand SU patterns to support the field in developing tailored individual, group, and systems-level interventions that are trauma-responsive and culturally syntonic for JIC and their families.

Among the general adolescent population, previous studies report white adolescents as more likely to report SU compared to racially/ethnically minoritized adolescents (Johnston et al., 2020; Miech et al., 2020; Pamplin et al., 2020). However, these findings do not necessarily align with the juvenile justice population. Contrary to the findings of past research, this current study found Black and Latinx JIC have an increased likelihood of SU compared to white JIC. These differences in SU by racial groups may be explained by risk levels associated with SU as a coping mechanism that may vary by a social, cultural, or contextual factor that is embedded in race. Studies report racially/ethnically minoritized adolescents may be influenced differently by risk factors that may result in increased susceptibility to SU compared to white adolescents. Racially/ethnically minoritized adolescents experience the compounding effects of childhood adversity and racism disproportionately and may increase vulnerability to SU (Widom et al., 2013). White JIC with similar ACE scores may have a decreased likelihood of SU due to culturally based perceptions on addiction and SU that align with race, such as SU being interpreted as socially acceptable (Burke et al., 2011; Mason et al., 2014; Moreno et al., 2009; Wells et al., 2001). Future research is needed to understand the compounding effects and to identify specific cultural differences among juvenile justice populations.

Though Black JIC were more than twice as likely to use substances, they were less likely to be diagnosed with a SUD, and the effects of ACEs on SUD were exacerbated for white JIC compared to Black and Latinx JIC. First, these results contrast with previous research indicating Black youth use substances at lower rates than white youth (Beach et al., 2016). Despite this, Black youth still suffer harsher consequences of SU, such as adverse health outcomes and involvement with the justice system compared to their white counterparts (Zapolski et al., 2014). Youth that are racially and ethnically minoritized are more likely than white youth to receive criminal sanctions for behavior such as substance misuse instead of being referred for SUD assessment and to diversion or outpatient treatment programs (Heaton 2018). Second, the findings may show the protective effects of racially/ethnically minoritized status on the impact of ACEs on SUD and can be interpreted in several different ways. Consider two broad categories: (1) racially/ethnically minoritized JIC who experienced ACEs are underdiagnosed but have an equal or higher prevalence of SUD, and (2) racially/ethnically minoritized JIC who experienced ACEs truly have a lower risk of SUD.

The relationship between ACEs and SUD among Black JIC may be underestimated. First, the data collection process had limitations that are discussed in a subsequent limitations section, and the unexpected findings may cause some to question the validity of the data. However, these findings align with prior studies of racial/ethnic differences in SUD that show that Black individuals have a lower prevalence of SUD compared to other racial/ethnic groups. Therefore, the finding is unlikely due to limitations in the data (Wu et al., 2011). Second, instrumentation validity and reliability in the PACT may be limited such that racial/ethnic disparities may be linked to the PACT assessment process and/or factors in the criminal justice system (Baglivio & Jackowski, 2013). Third, assuming the instrument is valid, interpersonal dynamics may be contaminating the results of the SUD screen. Bias or prejudices possessed by the screener may influence how racially/ethnically minoritized children’s responses and indicators are interpreted. This may perpetuate the criminalization of SUD among racially/ethnically minoritized JIC who are often funneled deeper into the criminal justice system while white JIC may be properly diagnosed and provided with treatment services. Black and Latinx JIC, who may be aware of racial biases, may lack trust in many institutions and researchers, especially when the examiner identifies as white (Armstrong et al., 2007; Yeager et al., 2017). This mistrust may negatively impact interactions between child and examiner, thus affecting treatment decisions. Assuming that the screening protocol and procedures are not vulnerable to interpersonal discrimination, interpersonal factors may still impede the process. Cultural or ethnic incongruence between the child and the examiner could contaminate the screening process in a way that shows a false protective effect of racially/ethnically minoritized status.

On the other hand, Black and Latinx adolescents may have access to certain resources that attenuate the effects of ACEs. The racial differences may be due to some confounding protective factors, such as religiosity, which is higher in Black and Latinx communities and has shown to have a protective effect on addiction (Borras et al., 2010). Second, racially/ethnically minoritized JIC who have experienced ACEs may be protected by being resilient to stress. People who are racially/ethnically minoritized endure such a degree of stress that their sensitivity to stressors may be reduced, and therefore, may be better protected from adverse outcomes (Jones & Neblett, 2016; Neblett et al., 2012; Pellegrini, 1990). Black and Latinx JIC are disproportionately exposed to family and community-level disadvantages such that they may become more resilient to subsequent stressors and the risk factors for SUD.

Racial/ethnic bias and systemic discrimination can lead to Disproportionate Minority Contact with the criminal justice system among individuals who are racially/ethnically minoritized (Lo et al., 2020). As a result, children who are racially/ethnically minoritized and have risk factors associated with SU are funneled into the system, while white children with similar risks have access to resources in the community that promotes care and protects them from justice involvement (Baskin-Sommers et al., 2016). Research suggests that Disproportionate Minority Contact is a major driver in the ease of racially/ethnically minoritized youth entering the system (Brinkley-Rubinstein et al., 2014; Rovner, 2014). This contributes to the racial/ethnic disparities within the cascade of care, and the juvenile justice system being a de facto substance use treatment resource for racially/ethnically minoritized JIC.

Addressing impacts of ACEs among JIC may require cultural considerations, such as the effects of ACEs on youth from racially/ethnically minoritized and disadvantaged communities. Though Black JIC tend to report less ACEs than white JIC (Baglivio et al., 2014), they suffer harsher consequences (Johnson, 2017a). In this study, the effect of ACEs on SU was pronounced for Black and Latinx JIC. This aligns with prior research (Folk et al., 2021). Trauma-informed approaches and trauma treatment programs must be culturally appropriate with evidence of effectiveness among Black, Latinx, and other individuals who are racially/ethnically minoritized. There is a critical need for juvenile justice staff (e.g., police officers, judges, treatment staff, and probation officers) to be well-versed in the effects and potential outcomes associated with ACEs, especially SU and SUD. The juvenile justice community and future research should prioritize the development of a treatment and intervention workforce that has the capacity to adopt and implement trauma-informed approaches that are sensitive to the unique needs of racially/ethnically minoritized JIC (Folk et al., 2021).

Limitations

The study had several limitations that must be considered. First, Florida JIC may not represent all JIC in the US. In addition, there was an oversampling of higher risk groups in the Full PACT data. Second, the temporal sequence or directionality between exposure and outcome cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional data. Future studies using longitudinal data can build upon this study. Third, researchers have begun to question the comprehensiveness of the ACEs score in capturing the breadth of childhood trauma, including nuances in frequency and timing of exposure (Anda et al., 2020). Although ACEs were examined retrospectively in the current study, research has shown that retrospective reports of ACEs can still provide meaningful information to the field (Reuben et al., 2016; Rogers et al., 2021). The current study was able to pinpoint ACEs that occurred among JIC before the age of 18. Fourth, the reliance on youth self-reports for measures such as SU and delinquency may have resulted in under-reporting due to recall and/or social desirability bias (Huizinga & Elliott, 1986). Lastly, examining the level of severity of SUDs among this sample was beyond the scope of the study. In addition, the SU variable included many heterogeneous substances (e.g., alcohol, heroin, marijuana). Future research would benefit from assessing the severity of SUDs and accounting for substances individually to highlight specific outcomes that may be unique to racially/ethnically minoritized children involved in the juvenile justice system. Despite these limitations, this study was the first to investigate the relationships between ACEs, race, and SU and SUD using a large, diverse sample of JIC.

Conclusions

This study shows an association between ACEs and SU and SUD among JIC. Black and Latinx JIC were more likely to report current SU but less likely to have ever been diagnosed with a SUD. These results provide some empirical basis for developing trauma-informed and culturally appropriate screenings and interventions for SU among JIC. The effects of ACEs on SU among racially/ethnically minoritized youth found herein requires further investigation. In addition, potential racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis of SUD in the juvenile justice system should also be explored.

Table 2.

Characteristics of justice-involved children by their lifetime diagnosis for substance use disorder status.

| Overall (n = 24,944) | No SUD (n = 4,548) | SUD (n = 20,396) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | P | |

| ACEs+ mean(SD) | 4.95(2.07) | 4.57(2.13) | 5.04(2.05) | <.000 | |||

| Race | <.000 | ||||||

| White | 12,132 | 48.6 | 1,923 | 42.3 | 10,209 | 50.1 | |

| Black | 8,995 | 36.1 | 1,955 | 43.0 | 7,040 | 34.5 | |

| Latinx | 3,684 | 14.8 | 648 | 14.2 | 3,036 | 14.9 | |

| Other | 133 | 0.5 | 22 | 0.5 | 111 | 0.5 | |

| Sex | <.000 | ||||||

| Male | 20,326 | 81.5 | 3,565 | 78.4 | 16,761 | 82.2 | |

| Female | 4,618 | 18.5 | 983 | 21.6 | 3,635 | 17.8 | |

| Income | <.481 | ||||||

| Under $15k | 6,014 | 24.1 | 1,119 | 24.6 | 4,895 | 24.0 | |

| From $15k to $34,999 | 12,946 | 51.9 | 2,362 | 51.9 | 10,584 | 51.9 | |

| From $35k to $49,999 | 3,949 | 15.8 | 720 | 15.8 | 3,229 | 15.8 | |

| $50k & over | 2,035 | 8.2 | 347 | 7.6 | 1,688 | 8.3 | |

| Substance type | <.000 | ||||||

| Marijuana only | 5,882 | 23.6 | 679 | 14.9 | 5,203 | 25.5 | |

| Alcohol only | 581 | 2.3 | 127 | 2.8 | 454 | 2.2 | |

| Alcohol and marijuana only | 3,485 | 14.0 | 371 | 8.2 | 3,114 | 15.3 | |

| Illicit drugs | 3,513 | 14.1 | 184 | 4.0 | 3,329 | 16.3 | |

| Other DRUGS | 11,483 | 46.0 | 3,187 | 70.1 | 8,296 | 40.7 | |

| Current SU-related problems | <.000 | ||||||

| None | 17,074 | 68.4 | 3,921 | 86.2 | 13,153 | 64.5 | |

| Yes | 7,870 | 31.6 | 627 | 13.8 | 7,243 | 35.5 | |

| History of mental problems | <.000 | ||||||

| None | 19,686 | 78.9 | 3,679 | 80.9 | 16,007 | 78.5 | |

| Yes | 5,258 | 21.1 | 869 | 19.1 | 4,389 | 21.5 | |

| Adjudicated felonies | <.742 | ||||||

| None | 7,040 | 28.2 | 1,267 | 27.9 | 5,773 | 28.3 | |

| One | 9,771 | 39.2 | 1,813 | 39.9 | 7,958 | 39.0 | |

| Two | 4,981 | 20.0 | 905 | 19.9 | 4,076 | 20.0 | |

| Three or more | 3,152 | 12.6 | 563 | 12.4 | 2,589 | 12.7 | |

| HS enrollment status | <.000 | ||||||

| Enrolled or graduated | 10,174 | 40.8 | 2,287 | 50.3 | 7,887 | 38.7 | |

| Suspended | 1,565 | 6.3 | 342 | 7.5 | 1,223 | 6.0 | |

| Dropped out | 10,039 | 40.2 | 1,478 | 32.5 | 8,561 | 42.0 | |

| Expelled | 3,166 | 12.7 | 441 | 9.7 | 2,725 | 13.4 | |

Note. Data displayed as column percent.

Symbol “+” signifies that mean is reported with stand deviations (SD) in parentheses. HS = high school enrollment status at the time of assessment.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation matrix for Model 1.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Substance use | – | |||||||

| 2. ACEs | 0.13*** | – | ||||||

| 3. Race | 0.12*** | −0.12*** | ||||||

| 4. Female | −0.08*** | 0.16*** | −0.05*** | |||||

| Income | −0.11*** | −0.21*** | −0.16*** | −0.04*** | ||||

| 6. Mental problems | 0.07*** | 0.24*** | −0.15*** | 0.08*** | −0.02*** | |||

| 7. Felonies | 0.27*** | 0.02*** | 0.05*** | −0.24*** | −0.06*** | 0.001*** | ||

| 8. Enrollment status | 0.10*** | 0.24*** | 0.03*** | −0.03*** | −0.13*** | 0.04*** | 0.11*** |

Note: These data present Spearman’s correlation coefficients for all variables in Model 1.

p < 0.5

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

The data in this study were developed by and obtained from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (FLDJJ) in Tallahassee, Florida. Our team would like to especially acknowledge the dedicated professionals at FLDJJ for their work in managing the data and collaborating with investigators.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers 1K01DA052679 (Dr. Micah E. Johnson, PI), R25DA050735 (Dr. Micah E. Johnson, PI), R25DA035163 (Dr. Micah E. Johnson, USF Site PI), U01DA051039 (Dr. Micah E. Johnson, USF Site PI), and T32DA035167 (Dr. Linda B. Cottler, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent was not required. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida.

Data availability and sharing

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to participant confidentiality considerations. Aggregate data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Aalsma MC, Dir AL, Zapolski TC, Hulvershorn LA, Monahan PO, Saldana L, & Adams ZW (2019). Implementing risk stratification to the treatment of adolescent substance use among youth involved in the juvenile justice system: Protocol of a hybrid type 1 trial. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 14(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s13722-019-0161-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Porter LE, & Brown DW (2020). Inside the adverse childhood experience score: Strengths, limitations, and misapplications. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(2), 293–295. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, & Putt M (2007). Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 97(7), 1283–1289. 10.2105/ajph.2005.080762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Epps N, Swartz K, Huq MS, Sheer A, & Hardt NS (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1–17. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/scans/Prevalence_of_ACE.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, & Jackowski K (2013). Examining the validity of a juvenile offending risk assessment instrument across gender and race/ethnicity. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 11(1), 26–43. 10.1177/1541204012440107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin-Sommers AR, Baskin DR, Sommers I, Casados AT, Crossman MK, & Javdani S (2016). The impact of psychopathology, race, and environmental context on violent offending in a male adolescent sample. Personality Disorders, 7(4), 354–362. 10.1037/per0000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Barton AW, Lei MK, Mandara J, Wells AC, Kogan SM, & Brody GH (2016). Decreasing substance use risk among African American youth: Parent-based mechanisms of change. Prevention Science, 17(5), 572–583. 10.1007/s11121-016-0651-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Brown SM, Thompson SJ, Ferguson KM, & Langenderfer L (2015). Multiple victimizations before and after leaving home associated with PTSD, depression, and substance use disorder among homeless youth. Child Maltreatment, 20(2), 115–124. 10.1177/1077559514562859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borras L, Khazaal Y, Khan R, Mohr S, Kaufmann YA, Zullino D , & Huguelet P (2010). The relationship between addiction and religion and its possible implication for care. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(14), 2357–2410. 10.3109/10826081003747611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Craven KL, & McCormack MM (2014). Shifting perceptions of race and incarceration as adolescents age: Addressing disproportionate minority contact by understanding how social environment informs racial attitudes. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31(1), 25–38. 10.1007/s10560-013-0306-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, & Shillington AM (2017). Childhood adversity and the risk of substance use and delinquency: The role of protective adult relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 211–221. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Hellman JL, Scott BG, Weems CF, & Carrion VG (2011). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(6), 408–413. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CA, Barnes A, Papp J, D’amato C, Anderson VR, & Moses N (2020). Understanding the role of neighborhood typology and sociodemographic characteristics on time to recidivism among adjudicated youth. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(9), 1079–1096. 10.1177/0093854820924834 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carliner H, Gary D, McLaughlin KA, & Keyes KM (2017). Trauma exposure and externalizing disorders in adolescents: Results from the national comorbifity survey adolescent supplement. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(9), 755–764.e3. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carliner H, Keyes KM, McLaughlin KA, Meyers JL, Dunn EC, & Martins SS (2016). Childhood trauma and illicit drug use in adolescence: A population-based national comorbidity survey replication-adolescent supplement study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(8), 701–708. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-Y, Propp J, deLara E, & Corvo K (2011). Child neglect and its association with subsequent juvenile drug and alcohol offense. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28(4), 273–290. 10.1007/s10560-011-0232-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dierkhising CB, Ko SJ, Woods-Jaeger B, Briggs EC, Lee R, & Pynoos RS (2013). Trauma histories among justice-involved youth: Findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 20274. 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Lin H, Zhou L, Yan H, & He N (2014). Adverse childhood experiences and interaction with methamphetamine use frequency in the risk of methamphetamine-associated psychosis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142, 295–300. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, Chapman DP, Giles WH, & Anda RF (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott AL, Cottler LB, & Johnson ME (2018). Racial/ethnic disparities in referral for substance use disorder screening among Florida justice-involved children [Oral Presentation]. Presented at the College on Problems of Drug Dependence 80th Annual Scientific Meeting, San Diego, California. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk JB, Kemp K, Yurasek A, Barr-Walker J, & Tolou-Shams M (2021). Adverse childhood experiences among justice-involved youth: Data-driven recommendations for action using the sequential intercept model. The American Psychologist, 76(2), 268–283. 10.1037/amp0000769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day SH, & Coyne-Beasley T (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76. 10.2105/ajph.2015.302903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa NT, & Ford CL (2009). The foundation of modern racial categories and implications for research on Black/white disparities in health. Ethnicity & Disease, 19(2), 209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton LL (2018). Racial/ethnic differences of justice-involved youth in substance-related problems and services received. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(3), 363–375. 10.1037/ort0000312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, & Elliott DS (1986). Reassessing the reliability and validity of self-report delinquency measures. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 2(4), 293–327. 10.1007/bf01064258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME (2017a). Trauma, race, and risk for violent felony arrests among Florida juvenile offenders. Crime and Delinquency, 64(11), 1437–1457. 10.1177/0011128717718487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME (2017b). Childhood trauma and risk for suicidal distress in justice-involved children. Children and Youth Services Review, 83, 80–84. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ME, & Tran DX (2020). Factors associated with substance use disorder treatment completion: A cross-sectional analysis of justice-involved adolescents. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 15(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s13011-020-00332-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SD, Cottler LB, O’Leary CC, & Ben Abdallah A (2010). The association of trauma and PTSD with the substance use profiles of alcohol- and cocaine-dependent out-of-treatment women. The American Journal on Addictions, 19(6), 490–495. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00075.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SD, Striley C, & Cottler LB (2006). The association of substance use disorders with trauma exposure and PTSD among African American drug users. Addictive Behaviors, 31(11), 2063–2073. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME (2020). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use. 1975-2019: Overview key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SCT, & Neblett EW (2016). Racial-ethnic protective factors and mechanisms in psychosocial prevention and intervention programs for Black youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(2), 134–161. 10.1007/s10567-016-0201-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakade M, Duarte CS, Liu XH, Fuller CJ, Drucker E, Hoven CW, Fan B, & Wu P (2012). Adolescent substance use and other illegal behaviors and racial disparities in criminal justice system involvement: Findings from a U.S. national survey. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1307–1310. 10.2105/ajph.2012.300699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DK, Joe GW, Morse DT, Smith C, Knudsen H, Johnson I, Wasserman GA, Arrigona N, McReynolds LS, Becan JE, Leukefeld C, & Wiley TRA (2019). Organizational context and individual adaptability in promoting perceived importance and use of best practices for substance use. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 46(2), 192–216. 10.1007/s11414-018-9618-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin H, Aykanian A, Dean E, & Lee E (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and substance use history among vulnerable older adults living in public housing. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 60(6–7), 428–442. 10.1080/01634372.2017.1362091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, & Taxman FS (2020). Using latent class analysis to identify the complex needs of youth on probation. Children and Youth Services Review, 115, 105087. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeTendre ML, & Reed MB (2017). The effect of adverse childhood experiences on clinical diagnosis of a substance use disorder: Results of a nationally representative study. Substance Use & Misuse, 52(6), 689–697. 10.1080/10826084.2016.1253746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CC, Ash-Houchen W, Gerling HM, & Cheng TC (2020). From childhood victim to adult criminal: Racial/ethnic differences in patterns of victimization-offending among Americans in early adulthood. Victims & Offenders, 15(4), 430–456. 10.1080/15564886.2020.1750517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan-Greene P, Kim BKE, & Nurius PS (2020). Adversity profiles among court-involved youth: Translating system data into trauma-responsive programming. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104, 104465. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MC, Roberts JM, & Klingele C (2016). Collateral consequences of criminal convictions: Law, policy and practice. Thomas West. http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_bks/56 [Google Scholar]

- Mason MJ, Mennis J, Linker J, Bares C, & Zaharakis N (2014). Peer attitudes effects on adolescent substance use: The moderating role of race and gender. Prevention Science, 15(1), 56–64. 10.1007/s11121-012-0353-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Morales M, Cranford JA, & Boyd CJ (2007). Does early onset of non-medical use of prescription drugs predict subsequent prescription drug abuse and dependence? Results from a national study. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 102(12), 1920–1930. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02015.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Haegerich TM, & Simon T (2020). Adverse childhood experiences increase risk for prescription opioid misuse. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 41(2), 139–152. 10.1007/s10935-020-00578-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, & Bachman JG (2020). Trends in reported marijuana vaping among US adolescents, 2017–2019. JAMA, 323(5), 475–476. 10.1001/jama.2019.20185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno MA, Briner LR, Williams A, Walker L, & Christakis DA (2009). Real use or “real cool”: Adolescents speak out about displayed alcohol references on social networking websites. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(4), 420–422. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW Jr., Rivas-Drake D, & Umana-Taylor AJ (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 295–303. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pamplin JR, Susser ES, Factor-Litvak P, Link BG, & Keyes KM (2020). Racial differences in alcohol and tobacco use in adolescence and mid-adulthood in a community-based sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(4), 457–466. 10.1007/s00127-019-01777-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini DS (1990). Psychosocial risk and protective factors in childhood. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 11(4), 201–209. 10.1097/00004703-199008000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Schroeder F, Hogan S, Ramrakha S, Poulton R, & Danese A (2016). Lest we forget: Comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 57(10), 1103–1112. 10.1111/jcpp.12621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JA, & Grey CM (2005). Pathways to recurrent trauma among young Black men: Traumatic stress, substance use, and the “code of the street”. American Journal of Public Health, 95(5), 816–824. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CJ, Forster M, Grigsby TJ, Albers L, Morales C, & Unger JB (2021). The impact of childhood trauma on substance use trajectories from adolescence to adulthood: Findings from a longitudinal Hispanic cohort study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 120, 105200. 10.1016/jxhiabu.2021.105200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovner J (2014). Disproportionate minority contact in the juvenile justice system. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Disproportionate-Minority-Contact-in-the-Juvenile-Justice-System.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Scheidell JD, Quinn K, McGorray SP, Frueh BC, Beharie NN, Cottler LB, & Khan MR. (2018). Childhood traumatic experiences and the association with marijuana and cocaine use in adolescence through adulthood. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 113(1), 44–56. 10.1111/add.13921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, McDonald SE, & Conley D (2018). Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and substance use among young adults: A latent class analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 187–192. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, & Saldana L (2013). Trauma, delinquency, and substance use: Co-occuring problems for adolescent girls in the juvenile justice system. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 22(5), 450–465. 10.1080/1067828x.2013.788895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinney E, Yeide M, Feyerherm W, Cohen M, Stephenson R, & Thomas C (2016). Racial disparities in referrals to mental health and substance abuse services from the juvenile justice system: A review of the literature. Journal of Crime and Justice, 39(1), 153–173. 10.1080/0735648X.2015.1133492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort-Schel J, Mercera G, Wissink I, Mink E, Van der Helm P, Lindauer R, & Moonen X (2018). Adverse childhood experiences in children with intellectual disabilities: An exploratory case-file study in Dutch residential care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2136. 10.3390/ijerph15102136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman GA, McReynolds LS, Schwalbe CS, Keating JM, & Jones SA (2010). Psychiatric disorder, comorbidity, and suicidal behavior in juvenile justice youth. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(12), 1361–1376. 10.1177/0093854810382751 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, & Sherbourne C (2001). Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(12), 2027–2032. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja S, Wilson HW, Allwood M, & Chauhan P (2013). Do the long-term consequences of neglect differ for children of different races and ethnic backgrounds? Child Maltreatment, 18(1), 42–55. 10.1177/1077559512460728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ (2012). The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass and public policy. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff KT, Cuevas C, Intravia J, Baglivio MT, & Epps N (2018). The effects of neighborhood context on exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACE) among adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system: Latent classes and contextual effects. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2279–2300. 10.1007/s10964-018-0887-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Pan JJ, & Blazer DG (2011). Racial/ethnic variations in substance-related disorders among adolescents in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(11), 1176–1185. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrick P, & Atkinson K (2021). Examining the relationship between childhood trauma and involvement in the justice system. National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/examining-relationship-between-childhood-trauma-and-involvement-justice-system [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Purdie-Vaughns V, Hooper SY, & Cohen GL (2017). Loss of institutional trust among racial and ethnic minority adolescents: A consequence of procedural injustice and a cause of life-span outcomes. Child Development, 88(2), 658–676. 10.1111/cdev.12697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, & Smith GT (2014). Less drinking, yet more problems: Understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 188–223. 10.1037/a0032113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to participant confidentiality considerations. Aggregate data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.