The survival of a subset of carcinoma cells is dependent on the function of the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex, which prevents aberrant activation of the integrated stress response via degradation of the HRI kinase.

Abstract

Systematic identification of signaling pathways required for the fitness of cancer cells will facilitate the development of new cancer therapies. We used gene essentiality measurements in 1,086 cancer cell lines to identify selective coessentiality modules and found that a ubiquitin ligase complex composed of UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4 is required for the survival of a subset of epithelial tumors that exhibit a high degree of aneuploidy. Suppressing BIRC6 in cell lines that are dependent on this complex led to a substantial reduction in cell fitness in vitro and potent tumor regression in vivo. Mechanistically, BIRC6 suppression resulted in selective activation of the integrated stress response (ISR) by stabilization of the heme-regulated inhibitor, a direct ubiquitination target of the UBA6/BIRC6/KCMF1/UBR4 complex. These observations uncover a novel ubiquitination cascade that regulates ISR and highlight the potential of ISR activation as a new therapeutic strategy.

Significance:

We describe the identification of a heretofore unrecognized ubiquitin ligase complex that prevents the aberrant activation of the ISR in a subset of cancer cells. This provides a novel insight on the regulation of ISR and exposes a therapeutic opportunity to selectively eliminate these cancer cells.

See related commentary Leli and Koumenis, p. 535.

This article is highlighted in the In This Issue feature, p. 517

INTRODUCTION

The identification of small-molecule inhibitors of mutant oncogenes has in some cases led to dramatic tumor responses. Despite these successes, many cancers do not harbor mutations in druggable oncogenes, and single-agent therapies rarely lead to complete tumor regression. To systematically identify genes whose expression is required for the proliferation and/or survival of a subset of cancer cell lines, we and others have developed genome-scale approaches to perform loss-of-function [RNA interference (RNAi) and CRISPR–Cas9] screens in hundreds of cancer cell lines to identify context-specific essential genes (1–7). These efforts have led to the identification of WRN as a synthetic lethal target in microsatellite unstable cancers, PRMT5 as a gene essential in MTAP-deleted tumors, and selective EGLN1 dependency in clear-cell ovarian cancers (8–12).

Most of these studies focused on the identification of single genes required for cell fitness in particular contexts. However, other studies have used the pattern of gene dependency across these panels of cancer cell lines to uncover genes that are coessential in selective contexts, leading to the identification of gene networks and protein complexes (13–21). For example, this approach enabled the identification of new components of known protein complexes by finding orphan genes that showed a similar pattern of gene dependency across these cell lines (18, 21). This approach, when combined with the elucidation of the context associated with gene essentiality, should facilitate the identification of signaling pathways and protein complexes as cancer-specific vulnerabilities that could be exploited therapeutically.

The integrated stress response (ISR) is a signaling cascade activated by a wide variety of stress signals and supports the maintenance of protein homeostasis. Many different stress stimuli, including oxidative stress, viral infection, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, mitochondrial dysregulation, and amino acid deprivation, converge on the activation of one of the four kinases: heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI, also known as EIF2AK1), protein kinase R (PKR), protein kinase R–like ER kinase (PERK), or general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2; refs. 22–24). These kinases, once activated, mediate phosphorylation and inactivation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2), resulting in a general reduction of protein synthesis. Previous studies have demonstrated aberrant activation of ISR signaling in cancer and its contribution to cancer pathogenesis (25–27). However, these studies did not address whether the selective activation of this pathway results in a unique vulnerability in cancer.

Here, we analyzed a cancer dependency dataset composed of CRISPR–Cas9 loss-of-function screens performed in 1,086 cancer cell lines to identify coessential gene modules. This approach identified protein complexes and signaling pathways required for the fitness of subsets of cancer cell lines, among which was a previously unrecognized functional ubiquitin ligase complex that enables the survival of a subset of epithelial cancer cells by preventing excessive activation of ISR in these cells. This study reveals a novel mechanism of ISR regulation and a potentially exploitable vulnerability associated with the activation of the ISR in cancer cells.

RESULTS

The BIRC6 Ubiquitination Module Identified by Coessentiality Analyses

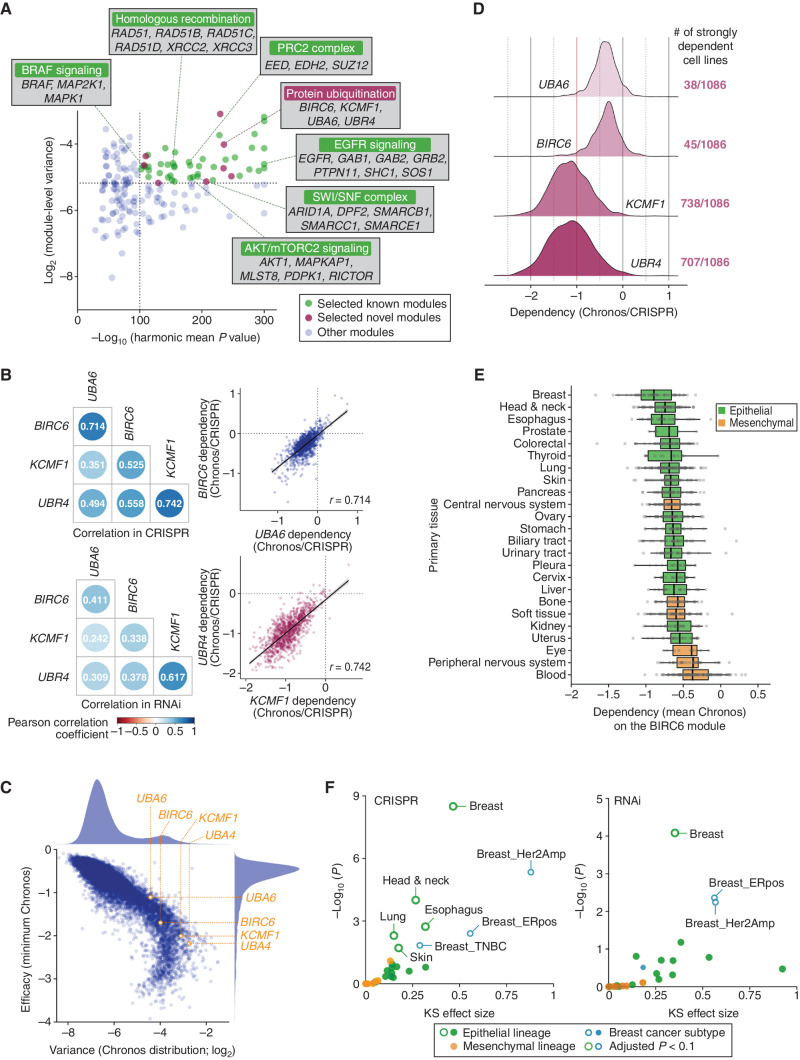

To identify signaling pathways or protein complexes that are selectively essential, we sought to find clusters of genes that exhibit coessential profiles, hereafter referred to as coessentiality modules, across a large number of cancer cell lines. We employed a regression approach based on the principle of generalized least squares (GLS) to calculate coessentiality relationships between genes (ref. 28; Supplementary Fig. S1A). We applied this approach to a dataset derived from the CRISPR–Cas9 loss-of-function screens performed in 1,086 cell lines in the Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) Project to generate a list of the most significant gene–gene interactions, from which we identified coessentiality gene modules composed of ≥3 genes (16). Subsequently, to select modules composed of genes with highly selective and correlated essentiality profiles, we filtered these modules based on (i) the variance score of the essentiality across different cell line models and (ii) the harmonic mean P value of the top three most closely correlated interactions within the module. This approach led us to compile a list of the top 50 coessentiality modules (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S1B; Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

Cell type–specific role of the UBA6/BIRC6/KCMF1/UBR4 module revealed by the coessentiality analysis. A, Based on the significance of correlation and the variance of essentiality, we selected 50 top coessential gene modules, which included 42 modules for which the functional interactions of the constituent genes have already been reported (green dots) and eight modules that contain previously unassociated gene pair(s) (pink dots). B, Correlation of the essentiality of the four genes that comprise the BIRC6 module (UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4). The Pearson correlation coefficients between the dependency profiles of the indicated gene pairs in both CRISPR (top) and RNAi (bottom) datasets (left) are shown. The correlations between UBA6 and BIRC6 (r = 0.714) as well as KCMF1 and UBR4 (r = 0.742) in the CRISPR dataset are also shown individually in the scatter plots (right). C, All these genes exhibited dependency profiles with both high variance (>89th percentile among all genes) and strong efficacy (>83rd percentile of all genes), the latter being defined by the minimum dependency score (Chronos) across all cell lines. D, The dependency profiles of the four genes constituting the BIRC6 module. UBA6 and BIRC6 were strongly essential (>90% probability of dependency) in a small subset of cell lines, while KCMF1 and UBR4 were strongly essential in the majority (>65%) of cell line models. E, Dependency on the BIRC6 module per tissue type. The mean Chronos (mChronos) scores of the four genes comprising the BIRC6 module were plotted per tissue type. The dependency on this module is enriched in epithelial tissue–derived cancer cells. F, Significance of the lineage/subtype enrichment of the BIRC6 module gene dependencies in the CRISPR and RNAi screens. The distribution of mChronos or mean DEMETER2 scores in the individual lineages/subtypes was compared with the corresponding distribution in all the other cell lines within the dataset. The effect size and significance, determined by the two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (KS), were plotted. ERpos, estrogen receptor positive; Her2Amp, Her2 amplified; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Among these 50 coessentiality modules were protein complexes and signaling pathways previously implicated in the pathogenesis of particular cancer types (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S1B), which confirmed that this approach identifies pathways critical for the survival of specific cancers. We also identified hitherto unrecognized coessentiality complexes including a module composed of four genes involved in protein ubiquitination: UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4 [harmonic mean P = 5E-236, log2(variance) = −4.02]. We refer to these coessential genes as the BIRC6 module. These four genes were strongly correlated not only in the CRISPR screen dataset, but also in a dataset of genome-scale RNAi screens performed in 707 cancer cell lines, as revealed by the significant association of these profiles for any combination of two genes in the module (P < 7E-33, CRISPR; P < 2E-8, RNAi; Fig. 1B).

To further evaluate the potential of the BIRC6 module genes as selective and exploitable cancer vulnerabilities, we examined the essentiality profiles of these genes individually and observed that each of the four genes exhibited an essentiality profile with both high variance (>89th percentile) and strong phenotype (>83rd percentile), the latter defined by the minimum dependency score across all cell lines calculated using Chronos gene effect (ref. 29; Fig. 1C). Among these four genes, UBA6 and BIRC6 were strongly essential (>90% probability of dependency) in only 3.5% and 4.1% of the cell lines, respectively. In contrast, KCMF1 and UBR4 were strongly essential in 68.0% and 65.1% of the cell lines, respectively (Fig. 1D). Together, these findings indicated that the E3 ligases (KCMF1 and UBR4) are essential for the viability of a wider range of cancer cell types, while the E1 (UBA6) and E2 (BIRC6) enzymes are preferentially essential in specific cancer subtypes, suggesting that the selectivity to specific cancer types is dictated by UBA6 and BIRC6. Indeed, the KCMF1/UBR4 heterodimeric E3 enzyme is known to cooperate with the RAD6A and UBE2D3 E2 enzymes for the regulation of lysosomal protein degradation and ER-associated degradation of membrane-embedded substrates (ERAD-M), respectively (30, 31). Hence, the KCMF1/UBR4 heterodimer has broad biological functions beyond working with the other members of the BIRC6 module, which appears to account for the widely essential function of these E3 ligases.

To evaluate essentiality of the BIRC6 module in individual cancer types, we calculated the mean of the Chronos gene effect values for the four constituent genes in each cell line and plotted per cancer type. We found that epithelial-derived cell lines were generally more dependent on the BIRC6 module than mesenchymal tissue–derived cancer cell lines and the dependency on this module was particularly enriched in breast, head and neck, and esophageal cancers (Fig. 1E; Supplementary Fig. S1C). Consistently, each of the genes in the module also exhibited enrichment in head and neck cancer (P < 7E-4 for all the genes; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), esophageal cancer (P < 0.02 for all the genes), breast cancer in general (P < 1E-3 for all the genes), and HER2-amplified breast cancer specifically (P < 1E-3 for all four genes; Fig. 1F; Supplementary Fig. S1D). The strong correlation of essentiality profiles, potential functional link to protein ubiquitination, as well as the strongly and selectively essential nature of two of the components (UBA6 and BIRC6) together prompted us to study this module further.

In Vitro and In Vivo Validation of BIRC6 Dependency

We validated the dependency of the members of the BIRC6 module in individual cell lines. We identified single-guide RNAs (sgRNA) specific for UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4 and assessed the consequences of deleting each of these genes in lineage-matched cell lines that are either dependent or nondependent on this module as categorized by the mean Chronos score for the four genes (mean Chronos score < −1.62 for dependent and > −0.83 for nondependent). Using a 7-day cell viability assay, we found that the depletion of each of these genes reduced the proliferation and survival of the dependent cell lines to a significantly larger extent than the nondependent cell lines (P < 9E-6 for all four genes; Supplementary Fig. S2A). Although KCMF1 and UBR4 scored as less selective vulnerabilities, we found a differential dependency in this short-term viability assay. Among the four members of the module, the knockout of BIRC6 and KCMF1 induced a particularly robust decrease in cell viability comparable to that of common essential genes (0.67- to 1.1-fold). The strong effect on cell fitness caused by BIRC6 depletion, together with the selective profile of BIRC6 dependency, suggested that this E2 ligase is a key component of the module, leading us to focus on this enzyme in our subsequent studies.

We proceeded to test the dependency on BIRC6 in an extended panel of cell lines using additional sgRNAs (sgBIRC6-1 and sgBIRC6-5). We found that these sgRNAs suppressed BIRC6 expression equally well in the dependent and nondependent cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S2B). However, while BIRC6 knockout significantly reduced cell viability in all of the dependent cell lines, the effects on the nondependent cell lines approximated those of cutting controls (Fig. 2A). To validate these results with an orthogonal assay, we also performed a 14-day clonogenic growth assay using two dependent and two nondependent cell lines. Here again, we observed that the depletion of BIRC6 resulted in reduced cell viability selectively in the dependent cell lines (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. S2C), which reinforced the selective nature of the BIRC6 essentiality. The knockout of the BIRC6 gene in mice results in a perinatal lethality due to a defect in placental development (32, 33), hindering the assessment of the effect of suppressing BIRC6 in adult murine tissues. Accordingly, we also tested BIRC6 knockdown in two nontransformed cell types, the MCF10A mammary epithelial cells and the BJ fibroblasts, and found that this knockdown was unable to reduce cell viability in both cell types (Supplementary Fig. S2D and S2E). Collectively, these observations indicated that BIRC6 is selectively essential in a subset of cancer cells and that this E2 ligase is dispensable in at least certain kinds of nontransformed cell types.

Figure 2.

Validation of BIRC6 dependency in vitro and in vivo.A, Consequences of CRISPR-mediated BIRC6 knockout on cell viability. Five putatively dependent cells and six putatively nondependent cells [as defined by Chronos score (see Methods)], all of which constitutively express Cas9, were analyzed using an ATP-based assay 7 days after transducing an sgRNA against BIRC6 (three different sgRNA sequences were tested). Viability scores relative to the average viability of cells transduced with cutting control sgRNAs and the average viability of cells with knockout (KO) of common essential genes are shown. Values = means ± SD (n = 9). ****, P < 0.0001 (dependent vs. nondependent; for each guide). B, Consequences of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi)–mediated BIRC6 knockdown on long-term cell fitness. Clonogenic growth of the cells was evaluated 14 days after the transduction of an all-in-one CRISPRi construct targeting the indicated gene. Two sgRNA sequences against BIRC6 were tested. Presented are the representative images of cells with crystal violet staining (left) and the mean staining intensities per sample (n = 3, right). *, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001 (sgCiCh2-2 vs. sgCiBIRC6). C and D, Cell cycle (C) and cell death (D) analysis following BIRC6 knockout. Cas9-expressing derivatives of indicated cells were transduced with a cutting control sgRNA (sgCh2-2) or an sgRNA targeting BIRC6 (sgBIRC6-1, sgBIRC6-4). Cells were harvested 4 (C) or 7 (D) days later, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry. In C, the proportion of cells in the S-phase was reduced upon BIRC6 knockout in the three dependent models, but not in the three nondependent models. In D, the proportion of dead cells (late apoptosis + nonapoptotic death + early apoptosis) was increased following the knockout of BIRC6 in all of the three dependent cell lines, but only one of the three nondependent cell lines. ns, P ≥ 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 (n = 3). E–G,In vivo validation of the BIRC6 dependency. In E, ZR751 breast cancer cells expressing a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible shRNA against BIRC6 (shBIRC6–2) were implanted into the mammary fat pads of NRG mice. Following tumor formation, some of these mice were treated with DOX, while others were left untreated. In F and G, KYSE450 esophagus cancer cells (F) and HCC95 lung cancer cells (G), both of which were engineered to express an sgRNA against BIRC6 in a tamoxifen (TAM)-inducible fashion, were implanted subcutaneously via intraperitoneal injection (IP) into the NSG (NOD-scid Il2rg−/−) mice. Following tumor formation, some mice were injected with TAM, while others were treated with vehicle control. In both cases, the tumor growth is plotted to compare the two different groups of mice. Data are represented as means ± SEM [n = 8 (Keep w/o TAM group, G), 9 (Keep w/o TAM and TAM(-) groups, F; TAM hereafter group, G), 10 (Keep w/o DOX and DOX(-) groups, E; TAM hereafter and TAM (+) groups, F; TAM(-) and TAM(+) groups, G), 12 (DOX hereafter and DOX (+) groups, E)]. ns, P ≥ 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001 (for each of the last five time points for the tumor growth curves). All the experiments were performed twice except for A, which was conducted three times, and E–G, which were conducted once.

To gain insight into the mechanism by which BIRC6 depletion affects cell viability, we assessed cell-cycle profiles and apoptosis levels following BIRC6 knockout in three dependent and three nondependent cell lines. We found that BIRC6 depletion led to a consistent reduction in the proportion of cells in S-phase in the three dependent but not the three nondependent cell lines (P < 2E-3 for all the dependent cells, P > 0.2 for all the nondependent cells; Fig. 2C). Using Annexin V staining, we also found an induction of both early and late apoptosis in all of the three dependent but only one of the nondependent cell lines following BIRC6 depletion (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Fig. S2F). Hence, BIRC6 suppression affects both proliferation and survival of dependent cell lines.

Having confirmed the selective essentiality of BIRC6 in vitro, we next sought to evaluate the effects of BIRC6 suppression in vivo, specifically the effects on tumor growth and maintenance. First, we generated a doxycycline-inducible short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting BIRC6 and tested its efficacy and specificity in vitro in the ZR751 estrogen receptor (ER)–positive breast cancer cell line model (Supplementary Fig. S3A–S3C). Thus, we tested two different BIRC6-targeting shRNA sequences: one that matches completely with the BIRC6 sequence (shBIRC6-2) and the other targeting the same sequence but with a mismatch that eliminates the on-target effects of the shRNA while largely maintaining its off-target effects (ref. 34; shBIRC6-2-C911; Supplementary Fig. S3A). We found that the introduction of the on-target shRNA in the ZR751 cells had a far more profound effect on the viability of these cells (>90% reduction in cell viability in 14 days) than did the introduction of the mutant shRNA (20%–30% reduction in cell viability; Supplementary Fig. S3B and S3C). This observation confirmed that the toxic effect of the introduction of shBIRC6-2 shRNA in the ZR751 cells is attributable largely to its on-target effect. We subsequently implanted these cells orthotopically into the mammary fat pads of NOD-Rag1−/−Il2rg−/− (NRG) mice. After tumors formed (∼150 mm3), we randomized equal numbers of mice to control feed or feed supplemented with doxycycline. We observed robust tumor regression upon knockdown of BIRC6 in the doxycycline-fed group of mice (Fig. 2E; Supplementary Fig. S3D). In addition to regression of the primary tumor, we also observed that suppression of BIRC6 led to a greater than 10-fold reduction in metastatic burden in the lungs and liver (Supplementary Fig. S3E).

To further validate the robust antitumor effect of BIRC6 suppression and the relevance of this dependency beyond breast cancer, we extended our in vivo studies to encompass a BIRC6-nondependent esophageal cancer cell line (KYSE450) and a BIRC6-dependent lung cancer cell line (HCC95). First, we engineered both cell lines to express a Cas9 endonuclease, a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase, and an sgRNA targeting BIRC6. In these cells, tamoxifen treatment enables Cre expression, which subsequently drives expression of the BIRC6 sgRNA, leading to BIRC6 loss (ref. 35; Supplementary Fig. S3F and S3G). We transplanted these engineered KYSE450 and HCC95 cells subcutaneously into NSG (NOD-scid Il2rg−/−) mice. After tumors reached approximately 150 mm3, mice in each cohort were randomized into a tamoxifen treatment group or a corn oil vehicle control group. As expected, loss of BIRC6 in the BIRC6-nondependent KYSE450 cohort was unable to alter the growth rate of tumors (Fig. 2F; Supplementary Fig. S3H). In contrast, the BIRC6-dependent HCC95 cohort exhibited a robust response to BIRC6 loss, including rapid regressions of the primary tumors and substantial reductions of metastatic burden in the lungs and liver compared with controls (Fig. 2G; Supplementary Fig. S3H). Collectively, these observations demonstrated that BIRC6 is a highly selective dependency with a strong impact on in vivo tumor growth observed across different cancer lineages.

Biochemical Investigation of the BIRC6 Module

BIRC6 is a member of the Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein (IAP) family, a group of antiapoptotic proteins known to regulate caspases (36) that share a Baculovirus Inhibitor of apoptosis protein Repeat (BIR) domain (33). In addition, BIRC6 has a unique UBiquitin Conjugation (UBC) domain that mediates conjugation of ubiquitin to target proteins. This UBC domain makes BIRC6 a unique member of the IAP family that is a potential E2 enzyme in the protein ubiquitination machinery (37).

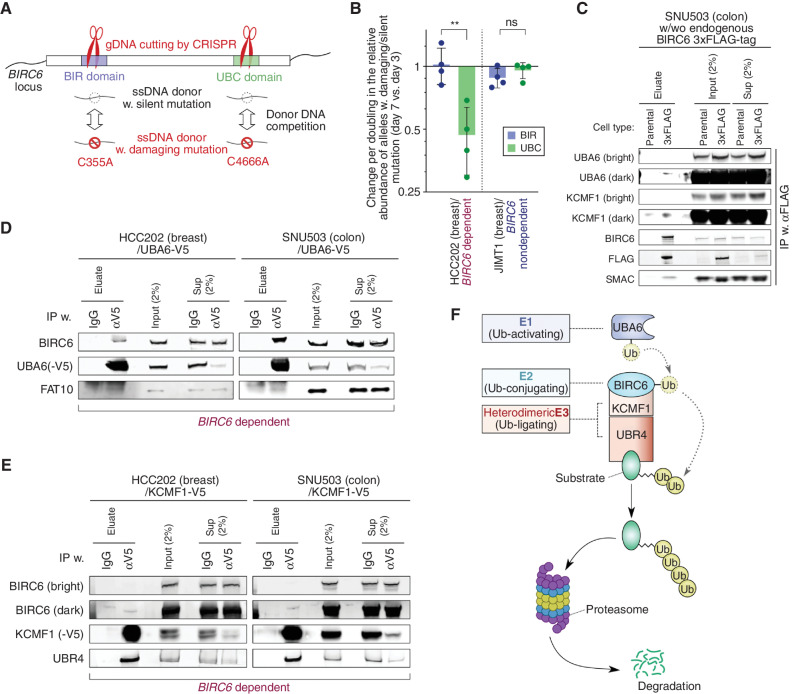

To assess whether the BIR and/or UBC domains were required for the observed dependency on BIRC6, we developed a competition assay where we directly compared the proliferation/survival of two different cell populations: one harboring a silent mutation and the other carrying a damaging mutation that disrupts the function of either the BIR or UBC domain. For the damaging mutations, we created mutants harboring a Cys to Ala change either at residue 355 or at residue 4666 to disrupt the BIR or UBC domain, respectively; both of these mutations were previously shown to eliminate the corresponding domain function (refs. 37–41; Fig. 3A). To perform this experiment, we delivered two donor DNA sequences (one with a silent and the other with a damaging mutation), guide RNAs [containing CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-acting CRISPR RNA (tracrRNA)] to introduce cleavage adjacent to these sites, and a recombinant Cas9 enzyme simultaneously into a dependent [HCC202: BIRC6 copy number (relative to ploidy) = 1.442] and a nondependent [JIMT1: BIRC6 copy number (relative to ploidy) = 1.194] breast cancer cell line. We harvested these cells 3 and 7 days after the nucleotide/protein transfer and measured the relative abundance of silent versus damaging mutations by PCR amplification and sequencing of these loci to identify differences in cell fitness in cells harboring these different mutation types (42).

Figure 3.

Biochemical demonstration of the BIRC6 complex assembly. A, Competition assay to evaluate the essentiality of each of the two functional domains of BIRC6 using a strategy to repair a CRISPR-mediated cleavage of the genomic locus corresponding to each of these domains (BIR and UBC) via homologous recombination. We show the two different donor DNAs that were introduced: one harboring a damaging mutation and the other containing a silent mutation. This assay scores the relative abundance of alleles with damaging versus silent mutations. ssDNA, single-strand DNA. B, Relative abundance of the damaging versus silent mutations in each of the two functional domains of BIRC6. Plotted is the change in the ratio of damaging over silent mutations at day 7 after the transduction of the Cas9/crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex relative to the corresponding ratio at day 3, normalized against the doubling time of the cells. Values = means ± SD (n = 4). ns, P ≥ 0.05; **, P < 0.01. C–E, Protein–protein interactions between the components of the BIRC6 module. In C, endogenously expressed BIRC6 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from the lysate of SNU503 cells that were engineered to have the 3xFLAG tag–encoding sequence inserted at the N-terminus of the BIRC6-encoding sequence. In D and E, exogenously expressed, V5-tagged UBA6 (D) and V5-tagged KCMF1 (E) were immunoprecipitated from the lysates of HCC202 and SNU503 cells. In all these cases, eluates, crude (input) lysates, and cleared (sup) lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. F, The BIRC6 module is composed of an E1 enzyme (UBA6), an E2 enzyme (BIRC6), and two E3 enzymes that have been shown to work cooperatively (KCMF1 and UBR4). All the experiments were performed twice except for B, which shows the summary of four independent experiments.

In the dependent HCC202 cells, the silent mutation for the UBC domain predominated over the damaging mutation on day 7 (1.5- to 3.4-fold increase per doubling, as compared to day 3, in the ratio of damaging vs. silent mutations). In contrast, we were unable to observe any significant changes to the ratio of silent versus UBC-damaging mutations in the nondependent JIMT1 cells. In addition, we found equivalent amounts of the silent and damaging mutations for the BIR domain of the HCC202 cells, suggesting that the BIR domain is dispensable for maintaining the viability of these dependent cells (Fig. 3B; Supplementary Fig. S4A). Collectively, these observations indicated that the BIRC6 E2 ubiquitin–conjugating enzyme function conferred by the UBC domain, but not the BIR domain function, was essential for the survival of the dependent cells.

We then analyzed the biochemical interactions between BIRC6 and the other members of the BIRC6 module: UBA6 (an E1 enzyme) and KCMF1/UBR4 (a heterodimeric E3 enzyme). Specifically, we assessed the interaction of BIRC6 with each of these proteins by coimmunoprecipitation. To analyze interactions with endogenous BIRC6, we used CRISPR–Cas9 genome engineering to insert a 3x-FLAG epitope tag–encoding sequence into the N-terminus of endogenous BIRC6 in the dependent SNU503 cell line (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S4B–S4D). Using these engineered cells, we isolated protein complexes using an anti-FLAG antibody and found that endogenous BIRC6 bound to both UBA6 and KCMF1 (Fig. 3C). Further supporting these interactions, when we expressed V5 epitope-tagged UBA6 (UBA6-V5) and KCMF1 (KCMF1-V5) proteins in the SNU503, HCC202, SW837, and JIMT1 cells, we found that both proteins coprecipitated with endogenous BIRC6 (Fig. 3D and E; Supplementary Fig. S3E and S3F). Collectively, these observations confirmed that UBA6 (E1), BIRC6 (E2), and KCMF1/UBR4 (E3) physically interact and suggested that these members together form a ubiquitin ligase complex, whose function in turn is crucial for the proliferation/survival of a subset of epithelial cancer cells (Fig. 3F).

Activation of the ISR following BIRC6 Depletion

To understand the mechanistic basis for the selective dependency on BIRC6, we profiled the transcriptional changes induced by BIRC6 suppression. Specifically, we introduced either an sgRNA targeting BIRC6 or a cutting control sgRNA (that cuts an intergenic region on chromosome 2) in each of the three dependent and three nondependent cell lines and profiled their transcriptional effects after 96 hours. We found that the expression of more than 700 genes changed significantly (FDR-adjusted P < 0.01) upon BIRC6 suppression in the dependent cell line models (Fig. 4A). In contrast, BIRC6 was the only gene that showed a significant change in expression in the nondependent models, strongly reinforcing the observation that BIRC6 depletion induces different responses in these two classes of cell lines. As anticipated, we observed the downregulation of genes associated with G2–M checkpoint progression and E2F target genes, as well as the upregulation of genes related to apoptosis. In addition, we found that genes involved in the unfolded protein response (UPR) were highly upregulated exclusively in cell lines that depend on BIRC6 expression for survival (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Selective activation of the ISR following BIRC6 depletion. A, Effects of BIRC6 depletion on gene expression. RNA samples were harvested 4 days after the transduction of either a control sgRNA (sgCh2-2) or an sgRNA targeting BIRC6 (sgBIRC6). The gene-level expression change [log-fold changes, or LogFC (sgBIRC6/sgCh2-2)] and the significance of the observed change [−log10 (P)] were plotted separately for the three dependent models and the three nondependent models. Green dots represent significant changes (adjusted P value < 0.01). B, Gene set enrichment analysis for the differentially expressed genes. The positions of the circles indicate the enrichment score for the individual hallmark gene sets, while the sizes of the circles reflect the significance of enrichment. These analyses were performed in HCC202 breast cancer cells and SNU503 colon cancer cells. C, Activation of p-eIF2a/ATF4 signaling following BIRC6 depletion in the dependent cell lines. The Cas9-expressing derivatives of the indicated cells were transduced with the indicated sgRNA, and their lysates were harvested 4 and 7 days later. The cell lysates were treated with arsenite (300 μmol/L, 3 hours), thapsigargin (1 μmol/L, 6 hours), or a vehicle control (DMSO). These lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for markers of the ISR, including p-eIF2S1, ATF4, and ATF3. Values represent the intensity of the p-eIF2α band relative to that of corresponding t-eIF2α band. D, Differential expression of the target genes for three different signaling arms of the UPR response, PERK–p-eIF2a/ATF4 pathway, ATF6 pathway, and IRE1/XBP1 pathway. The LogFCs in the expression levels of the individual transcriptional targets of these three signaling arms, observed in the RNA sequencing experiment shown in A, are indicated. ns, P ≥ 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001 (dependent vs. nondependent; LogFCs of the target genes that are specific only to the PERK–p-eIF2a/ATF4, ATF6, or IRE1/XBP1 pathway were compared between these two groups of cell lines). E, Schematic of the ISR. The four members of the EIF2AK family of kinases (GCN2, PKR, HRI, and PERK) are activated by discrete types of stress stimuli. However, their activation converges on the phosphorylation of eIF2a, resulting in the global shutdown of protein synthesis and selective induction of a subset of proteins including ATF4. The RNA sequencing experiment (A, B, D) was conducted once, while the experiment shown in C was conducted twice.

The UPR, also referred to as ER stress signaling, is an adaptive pathway activated in response to the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER. The ER stress signaling is composed of three discrete signaling arms: the phospho-eIF2α (p-eIF2α)/ATF4 pathway, the ATF6 pathway, and the IRE1/XBP1 pathway. Each of these branches transcriptionally activates both common and unique sets of genes (43–49). Indeed, treatment with arsenite and thapsigargin, compounds known to trigger the activation of the p-eIF2α/ATF4 pathway (50, 51), activated this signaling pathway in both dependent and nondependent cells (Fig. 4C), indicating that the p-eIF2α/ATF4 arm of UPR is intact in both BIRC6-dependent and -nondependent cells.

However, upon examination of the mRNA and protein expression changes resulting from BIRC6 suppression, we only found robust induction of targets of the p-eIF2α/ATF4 pathway in the dependent models. Specifically, upon depletion of BIRC6, we found phosphorylation of eIF2α and upregulation of protein levels of ATF4 and ATF3 (a transcriptional target of ATF4) in the two dependent cell lines, which coincided with the reduction of BIRC6 protein expression levels in these cells (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Fig. S5A). In contrast, BIRC6 knockout was unable to induce any sign of p-eIF2α/ATF4 pathway activation in the two nondependent cell lines (Fig. 4C). In addition, we did not find signs for the activation of ATF6 and IRE1/XBP1 pathways even in the dependent cells. Thus, the target genes of these two UPR branches were not noticeably upregulated (Fig. 4D), and neither ATF6 nuclear translocation nor splicing of XBP1 was observed following the knockout of BIRC6 (Supplementary Fig. S5B and S5C). We further found that the suppression of UBA6, KCMF1, and UBR4 resulted in the induction of ATF4 and ATF3 in the HCC202- and SNU503-dependent cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S5D). Together, these observations indicated that the selective activation of p-eIF2α/ATF4 signaling is a common outcome of the suppression of the BIRC6 complex in the dependent cells.

Canonical activation of the UPR involves induction of p-eIF2α/ATF4 signaling by an ER-resident kinase, PERK. However, this p-eIF2α/ATF4 signaling pathway can also be activated by any of the other three eIF2α kinases: HRI, PKR, and GCN2 (Fig. 4E). Each of these kinases is activated in response to specific stress signals (22, 24, 52). The stress-dependent activation of these eIF2α kinases and their ability to subsequently trigger p-eIF2α/ATF4 signaling are collectively referred to as the ISR (22, 24). The ISR is an adaptive pathway activated in response to diverse stress stimuli, and its activation leads to a reduction in global protein synthesis and the induction of selective proteins, including ATF4. These responses together maintain protein homeostasis and promote recovery of the cell. However, prolonged activation of ISR results in the blockade of cell growth and the induction of cell death (24). The selective activation of the p-eIF2α/ATF4 segment of the UPR upon depletion of BIRC6 in the dependent cells is reminiscent of ISR activation. Indeed, we observed the increased formation of stress granules, aggregates of inactive translation initiation complexes developed upon ISR activation (51), following depletion of either BIRC6 or UBR4 selectively in the dependent HCC202 cell line but not in the nondependent JIMT1 cell line (Supplementary Fig. S5E). Hence, the blockade of the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex results in the selective activation of the ISR.

HRI Triggers an ISR Upon BIRC6 Suppression

To test whether ISR activation was necessary for the loss of viability observed upon suppression of the BIRC6 complex, we used a small-molecule inhibitor of ISR (ISRIB) that counteracts the inhibitory effect of eIF2α phosphorylation on protein translation by promoting the assembly of the eIF2B guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) complex, a critical activator of the eIF2 translation initiation factor (51, 53, 54). We found that ISRIB treatment not only reverted the downstream effects of ISR activation, including the induction of ATF4 and ATF3 (Fig. 5A), but also rescued the loss of viability caused by UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4 depletion (Fig. 5B; Supplementary Fig. S6A). Furthermore, consistent with previous reports demonstrating the causal role of prolonged ISR activation in the induction of cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis (55–59), the defects in cell-cycle progression and survival, induced by the depletion of BIRC6 in HCC202 cells, were also rescued by treatment with ISRIB (Supplementary Fig. S6B and S6C). In contrast, the knockout of ATF4, a central transcriptional regulator of ISR, was unable to rescue the loss of viability caused by subsequent BIRC6 depletion, while the induction of established transcriptional targets of ATF4, including ATF3 and SESN2, was successfully blocked by this knockout (Supplementary Fig. S6D and S6E). These observations supported the notion that suppression of the BIRC6 complex causes loss of cell viability in an ISR-dependent but ATF4-independent fashion.

Figure 5.

HRI is a critical mediator of ISR induced by the inactivation of the BIRC6 complex. A and B, Blockade of BIRC6 depletion–induced ISR activation and loss of viability by ISRIB, an ISR inhibitor. HCC202-Cas9 and SNU503-Cas9 cells were transduced with the indicated sgRNA and maintained in either vehicle- or ISRIB-containing medium. In A, lysates were harvested 4 days later and subjected to immunoblotting. In B, cell viability was scored with an ATP-based viability assay 7 days later. Positive controls include sgRNAs targeting two common essential genes (POLR2D, SF3B1). ns, P ≥ 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001 (vs. corresponding ISRIB [-] sample). C, Schematic of the genome-scale screen to identify enhancers and suppressors of BIRC6 dependency. HCC202-Cas9 and SNU503-Cas9 cells were engineered to express a shRNA targeting BIRC6 in a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible manner. These cells were subsequently transduced with a genome-scale sgRNA library (Brunello) and subjected to DOX treatment 7 days after the library transduction. Cells were harvested after 7 days of DOX treatment and the relative abundance of individual sgRNAs in the genome of these cells was analyzed. D and E, Identification of genes whose knockout rescue or enhance the viability effect of BIRC6 knockdown. The significance of the change in sgRNA abundance between the genomic DNA (gDNA) of DOX-treated cells and the plasmid DNA (pDNA) of the library was scored using the hypergeometric distribution method and aggregated to the gene level and plotted together with the average LogFC (post-DOX sgDNA/pDNA) of the sgRNAs against the respective gene. HRI was among the strongest hits in both cell lines screened (HCC202 and SNU503; D). Correlation of the screen results between the two dependent cell lines is also plotted (E). The four genes that comprise the EIF2AK family of kinases are indicated by orange dots, while the genes with statistically significant (adjusted P value < 0.01) depletion/enrichment of corresponding sgRNAs are indicated by the green dots (in E, only genes with significant depletion/enrichment in both cells lines are indicated by the green dots). F, Blockade of BIRC6 depletion–induced ISR activation by the concomitant knockout of HRI. HCC202-Cas9 and SNU503-Cas9 cells were engineered to express either an sgRNA against HRI or PERK or a control sgRNA (sgCh2-2). These cells were subsequently transduced with a control sgRNA (sgAAVS1) or an sgRNA targeting BIRC6, and 4 days later, their lysates were harvested and analyzed. G, Rescue of the viability effect of BIRC6 knockout by the concomitant knockout of HRI. The cells expressing sgCh2-2, sgHRI, or sgPERK, used in F, were transduced with sgAAVS1 (negative control gene), an sgRNA against positive control genes, or an sgRNA against BIRC6, and their viability was scored 7 days later. ns, P ≥ 0.05; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001 (vs. corresponding sgCh2-2 sample). In A and F, values represent the intensity of the p-eIF2α band relative to that of the corresponding t-eIF2α band. In B and G, values = means ± SD [n = 3 (sgCh2-2 (B), sgAAVS1 (G)), 6 (positive ctrl, sgBIRC6)]. All the experiments were performed twice except for the genome-scale modifier screen (D and E), which was conducted once.

To elucidate the connection between BIRC6 depletion and ISR activation, we conducted a genome-scale CRISPR–Cas9 loss-of-function screen to identify suppressors of BIRC6 dependency. Specifically, we transduced a doxycycline-inducible shRNA targeting BIRC6 into two Cas9-expressing dependent cell lines (HCC202 and SNU503; Supplementary Fig. S6F and S6G), followed by infection of the Brunello genome-scale sgRNA library (60). We then induced BIRC6 suppression with doxycycline treatment, harvested the cells 7 days later, and assessed the abundance of individual sgRNAs (Fig. 5C). We subsequently calculated average log-fold change (LogFC) per gene compared with the library input and average P value of the observed changes (Fig. 5D), the former of which was strongly correlated (r = 0.583, Pearson) between the two cell lines tested (Fig. 5E). We found that HRI (EIF2AK1) scored as the most significantly enriched gene in the HCC202 cells (LogFC = 1.22, P = 3E-8, hypergeometric distribution) and third in the SNU503 cells (LogFC = 1.23, P = 5E-7, hypergeometric distribution; Fig. 5D and E; Supplementary Fig. S6H) but did not find significant enrichment of any other eIF2 kinases. This observation substantiated the selective requirement for HRI in response to BIRC6 depletion.

To confirm whether the depletion of HRI, but not other eIF2α kinases, rescued the viability loss from BIRC6 suppression, we first depleted HRI or PERK in HCC202 and SNU503 cells using CRISPR–Cas9 gene targeting and measured the effect of subsequent BIRC6 knockout on ISR activation and cell viability. We found that the depletion of HRI, but not that of PERK, blocked ISR activation, including phosphorylation of eIF2α and the elevated expression of ATF4 and ATF3, and impaired the decrease in cell viability, all of which were otherwise strongly induced upon BIRC6 knockout (Fig. 5F and G). Similarly, the depletion of PKR and GCN2 was also unable to prevent ISR activation caused by the suppression of BIRC6 in the SNU503 cells (Supplementary Fig. S6D). Moreover, the depletion of HRI rescued the observed loss of viability induced by knockout of the other module components—UBA6, KCMF1, and UBR4—in cells that were otherwise dependent on the expression of these genes (Supplementary Fig. S6I). Collectively, these observations implicated HRI as the key effector that links the suppression of the BIRC6 complex to the activation of ISR.

The BIRC6 Complex Ubiquitinates HRI

To identify putative targets of the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex and gain insights into the mechanism by which the suppression of this complex triggers HRI-mediated activation of ISR, we investigated the effects of BIRC6 suppression on the proteome. Specifically, we extracted the total cell protein from the HCC202 cells expressing an sgRNA cutting control, BIRC6-specific sgRNA, or UBR4-specific sgRNA and analyzed global protein expression by liquid chromatography followed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS-MS). We found extensive proteomic changes, involving approximately 1,000 significantly differentially expressed (FDR-adjusted P < 0.01) proteins among 9,843 fully quantified proteins, in both BIRC6-depleted and UBR4-depleted cells compared with the control cells (Supplementary Fig. S7A). We also found that BIRC6-knockout and UBR4-knockout cells exhibited strikingly similar proteomic changes (r = 0.839, Pearson), reinforcing the tight functional connection between these two genes (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Among the most highly elevated proteins after depletion of BIRC6 or UBR4 were genes whose expression was previously described to be altered by ISR activation (61–64), suggesting that many of the observed changes were due to the activation of ISR (Supplementary Fig. S7B).

To distinguish between the direct targets of the BIRC6 complex and a secondary effect resulting from ISR activation, we performed proteome profiling of the control and BIRC6-depleted derivatives of HCC202 cells in the presence and absence of ISRIB. As expected, ISRIB treatment reverted the vast majority of proteomic changes induced by the depletion of BIRC6, including the expression of many ISR-regulated gene products (Fig. 6A and B). Intriguingly, several proteins, including HRI, remained induced by BIRC6 depletion even in the presence of ISRIB. Indeed, HRI was the 25th and third most significantly upregulated protein following depletion of BIRC6 in the absence and presence of ISRIB, respectively (Fig. 6A). This observation was in stark contrast with the absence of HRI mRNA upregulation following BIRC6 depletion in the HCC202 cells (Supplementary Fig. S7C).

Figure 6.

Ubiquitination and stability of HRI are governed by the BIRC6 complex. A, Proteomic changes following BIRC6 depletion in the presence and absence of ISRIB. HCC202-Cas9 cells were transduced with either a control sgRNA (sgCh2-2) or an sgRNA targeting BIRC6 (sgBIRC6-4). Four days later, cells were harvested and subjected to LC/MS-MS. The magnitude [LogFC (sgBIRC6/sgCh2-2)] and significance [−log10 (P)] of the difference in protein expression between the control and BIRC6 knockout samples were plotted. Here and in B, the products of the genes that are transcriptionally regulated by ISR are indicated by the orange dots, while HRI is indicated by the green dot. B, Comparison of the BIRC6 depletion–induced proteomic changes in the presence and absence of ISRIB treatment. C, Elevated expression of HRI protein after depleting individual components of the BIRC6 complex. HCC202-Cas9 and SNU503-Cas9 cells were transduced with the indicated sgRNA, and their lysates were harvested 4 days later. Lysates of the cells treated with MG132 (10 μmol/L) or a vehicle control for 6 hours were also analyzed by immunoblotting. D, Stabilization of HRI following BIRC6 depletion. HCC202-Cas9 cells, transduced with either sgCh2-2 or sgBIRC6-4, were transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing HRI-V5. These cells were subsequently treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 50 μg/mL) and harvested at the indicated time points. Changes in the relative intensity between V5 and β-actin signals were plotted (right). Values = means ± SEM (n = 4). ****, P < 0.0001. E, Reduced HRI ubiquitination following BIRC6 depletion. HCC202-Cas9 cells that constitutively express HA-tagged Ubiquitin (HA-Ubiquitin) were further engineered to express HRI-V5 in a doxycycline (DOX)-inducible manner and then transduced with sgCh2-2 or sgBIRC6-4. These cells were subsequently treated with DOX (1 μg/mL, 48 hours), ISRIB (1 μmol/L, 48 hours), and/or MG132 (10 μmol/L, 6 hours), and their lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-V5 followed by immunoblotting. The ubiquitin chains attached to HRI-V5 were clearly detected in the control (sgCh2-2) sample treated with all the three reagents (DOX, ISRIB, MG132) but was less clear in the BIRC6 knockout (sgBIRC6-4) sample. The relative intensity between HA(-ubiquitin) and (HRI-)V5 signals for the samples cotreated with DOX, ISRIB, and MG132 was plotted (right). Values = means ± SD (n = 5). F, A physical interaction between UBR4 and HRI. HCC202-Cas9 cells were engineered to express HRI-V5 in a DOX-inducible manner. Following treatment with DOX (1 μg/mL, 48 hours), ISRIB (1 μmol/L, 48 hours), and/or MG132 (10 μmol/L, 6 hours), cells were harvested, and the lysates were subjected to anti-V5 IP and analysis by immunoblotting. G, Analysis of HRI phosphorylation status using a Phos-tag gel. HCC202-Cas9 cells, transduced with either sgCh2-2 or sgBIRC6-4, were transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing HRI-V5. HCC202-Cas9 cells without sgRNA transduction were also transfected with an HRI-V5–expressing plasmid and subsequently treated with either arsenite (300 μmol/L, 3 hours) or vehicle control (mock). Lysates of these cells were either treated with lambda phosphatase (+λPP) or left untreated (+λPP) and analyzed by immunoblotting using a Phos-tag gel and a standard protein (regular) gel. The knockout of BIRC6 resulted in the upregulation of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of HRI. H, Changes in expression of ISR markers upon HRI depletion. The Cas9-expressing derivatives of the indicated cells were transduced with either an sgRNA against HRI or a control sgRNA (sgCh2-2). Four days later, their lysates were harvested and analyzed for the expression levels of various ISR marker proteins. Relative intensity of the ATF3 and SESN2 bands, both of which were normalized to the intensity of the corresponding β-actin band, between sgCh2-2 and sgHRI samples were plotted. Values = means ± SD (n = 3). ****,P < 0.0001 (dependent vs. nondependent). The experiment shown in A and B was conducted once, the experiments shown in C and F were conducted twice, the experiments shown in G and H were conducted three times, the experiment shown in D was conducted four times, and the experiment shown in E was conducted five times.

We also found that HRI protein expression, as measured by immunoblotting, was elevated upon depletion of BIRC6 in two dependent cell lines, HCC202 and SNU503, both in the presence and absence of ISRIB (Figs. 4C and 5A). Moreover, the depletion of other members of the ubiquitination cascade (UBA6, KCMF1, and UBR4) and treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 all led to elevated HRI expression in these two cell lines (Fig. 6C). These observations precluded the possibility that HRI upregulation is a secondary change resulting from ISR activation and reinforced the idea that HRI is a direct effector of the BIRC6 complex that links this complex to ISR.

We next tested whether HRI stability was regulated by BIRC6 by examining the consequences of BIRC6 knockout using a cycloheximide chase assay. We found that an ectopically expressed, V5-tagged HRI protein (HRI-V5) exhibited a 2.6-fold longer half-life in BIRC6-depleted cells relative to control cells (t1/2 = 9.01 hours with sgBIRC6-4; t1/2 = 3.46 hours with sgCh2-2), indicating that BIRC6 depletion leads to stabilization of HRI (Fig. 6D). To investigate whether the BIRC6 complex directly ubiquitinates HRI, we ectopically HRI-V5 and HA-tagged ubiquitin in the HCC202 cells. We detected ubiquitinated forms of HRI in the presence of MG132 and ISRIB, and depletion of BIRC6 reduced the appearance of these ubiquitinated forms (Fig. 6E). Moreover, we found that ectopically expressed HRI-V5 protein coprecipitated with endogenously expressed UBR4, and this complex was more abundant in the presence of MG132 in both a dependent (HCC202; Fig. 6F) and a nondependent (JIMT1; Supplementary Fig. S7D) cell line, indicating the physical interaction between HRI and UBR4, the putative substrate-binding component of the BIRC6 complex (Fig. 3F). Together, these observations identified HRI as a direct ubiquitination/degradation target of the BIRC6 complex.

Prior work established that phosphorylation of HRI is a marker of its kinase activity (22). To test whether suppression of the BIRC6 complex induced changes in the phosphorylation status of HRI, we used the Phos-tag molecule to trap phosphorylated proteins in an SDS-PAGE gel (65). We found that depletion of BIRC6 led to increased expression of both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of HRI in HCC202 cells (Fig. 6G). Hence, the BIRC6 complex is likely to enhance the activity of HRI by stabilizing the expression of this kinase rather than actively triggering its phosphorylation.

In agreement with this notion, the depletion of HRI resulted in a consistent reduction in the expression of multiple ISR markers (including p-eIF2α, ATF4, ATF3, and SESN2) in the six BIRC6-dependent cell lines but not in the six BIRC6-nondependent cell lines (Fig. 6H). This observation suggested that HRI has constitutive activity in the dependent cells; therefore, the stabilization of the active form of HRI caused by the BIRC6 depletion in these cell types suffices to enhance HRI-mediated ISR activation. In contrast, in the nondependent cells, HRI is not active at the steady-state level, which may account for the absence of ISR activation following BIRC6 depletion in these cells. This difference in the constitutive activity of HRI between BIRC6-dependent and -nondependent cell lines suggests that steady-state activity of HRI dictates BIRC6 dependency.

To better understand the difference between BIRC6-mediated HRI regulation in the dependent and nondependent cell lines, we evaluated the effect of BIRC6 depletion on HRI expression in these distinct cell types. Interestingly, following BIRC6 suppression, the degree of HRI protein upregulation was significantly higher in the six BIRC6-dependent cell lines compared with the six BIRC6-nondependent cell lines (Supplementary Fig. S7E). Consistently, suppression of BIRC6 resulted in stabilization of HRI protein levels in the dependent HCC202 cell line but not in the nondependent JIMT1 cell line (Supplementary Fig. S7F). Collectively, these observations prompted us to conclude that BIRC6 modulates the HRI protein level more strongly in the dependent cells than in the nondependent cells and that these dependent cells require BIRC6-mediated HRI degradation as a strategy to prevent ISR, which otherwise is constitutively activated in these cells.

BIRC6 Dependency Is Enriched in Tumor Cells with High Degrees of Aneuploidy

We proceeded to assess the relevance of the presently studied signaling cascade—that is, the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex → HRI degradation → suppression of HRI-mediated ISR activation—to human cancer. Accordingly, we analyzed the expression levels of the genes whose products are involved directly in this signaling cascade in human normal versus tumor samples. This analysis revealed that the expression of HRI is strongly elevated in the tumor samples compared with the normal samples (a 2.26-fold increase in the median expression level; Supplementary Fig. S8A and S8B). We also found a strong correlation (r > 0.44) between the level of HRI expression and the expression levels of three components of the BIRC6 complex, namely, UBA6, BIRC6, and KCMF1, in the tumor samples (Supplementary Fig. S8C). Together, these observations suggested that the tumor cells with high HRI expression also require high expression levels of the BIRC6 complex components to degrade HRI and mitigate the effect of ISR that is otherwise activated by HRI, substantiating the relevance of the currently studied signaling cascade to human cancer.

The selective nature of the ISR response and cytotoxicity triggered by BIRC6 depletion, the strong antitumor effect following induced BIRC6 suppression in the xenograft models, and the evidence for the relevance of BIRC6 complex–mediated HRI degradation to human cancer together suggested the potential of BIRC6 as a therapeutic target in cancer. Because measurement of constitutive HRI activity in human tissue samples is challenging, we searched for genetic and/or expression features of the tumor cells that could be used to predict the sensitivity of the cells to BIRC6 suppression.

We first analyzed the dataset containing the genetic and expression features in the 1,086 DepMap cell lines that we used to identify the BIRC6 complex dependency. Specifically, we applied the random forest algorithm on this dataset to identify features that are important for predicting BIRC6 dependency (see Methods; Supplementary Fig. S9A). However, we were unable to identify a single dominant feature that accurately predicts BIRC6 dependency through this unbiased approach. Indeed, none of the features associated with the genes encoding the components of the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex (UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4) and its downstream effectors—including the critical ubiquitination substrate of the BIRC6 complex (HRI) and the major drivers of HRI-mediated ISR activation [eIF2α (EIF2S1), ATF4]—provided a precise prediction of BIRC6 dependency (Supplementary Fig. S9B–S9E).

We then generated and explored another dataset focused on cancer-associated genetic changes, which includes gain of function of oncogenes, loss of function of tumor suppressor genes, as well as features associated with global genomic changes such as chromosomal abnormality and microsatellite instability. With this dataset, we asked whether any of these features for the cancer-associated genetic changes could be used to predict the dependency on BIRC6. This analysis revealed a significant (r = −0.297, P = 2E-14) correlation between the degree of aneuploidy and BIRC6 dependency (Fig. 7A and B).

Figure 7.

Enrichment of BIRC6 dependency in aneuploidy-high cancer cells. A, Random forest modeling of BIRC6 dependency using aggregated scores for cancer-specific genetic changes (“cancer driver” feature set). The top 10 most important predictive features and the relative importance of each feature are indicated (left). For all the genetic dependencies profiled in the DepMap CRISPR screen (n = 17,386), the prediction accuracy of the random forest modeling with the “cancer driver” feature set was plotted (right). B, Correlation between BIRC6 dependency and aneuploidy score across different cell line models.C, Genetic dependencies correlated with the aneuploidy score. The correlation between the aneuploidy score and genetic dependency [−(Pearson r)] and the significance of correlation were plotted. D, Comparison of BIRC6 dependency between the group of cell lines with high aneuploidy scores (aneuploidy score ≥ 25, n = 107) and the group of cell lines with low aneuploidy scores (aneuploidy score ≤ 6, n = 118). ****, P < 0.0001. E, Comparison of aneuploidy score between the group of cell lines that is most strongly dependent on BIRC6 [bottom 100 in BIRC6 Chronos score (< −0.55)] and the group of cell lines that is least dependent on BIRC6 [top 100 in BIRC6 Chronos score (> −0.091)]. ****, P < 0.0001. F, A model for the antitumor effect of inhibiting the BIRC6 complex. HRI, whose mRNA expression is elevated in the tumor cells compared with normal cells of the same tissue across many different lineages (see Supplementary Fig. S8A and S8B), is activated under a variety of cancer-associated stress conditions, including, but not limited to, the stress arising from a high degree of aneuploidy. A subset of the tumor cells that exhibit a high level of steady-state HRI kinase activity appear to exploit HRI degradation by the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex as a strategy to prevent aberrant ISR activation and thus to survive. This highlights the potential of the BIRC6 complex as a therapeutic target to selectively eliminate these tumor cells.

Indeed, BIRC6, together with UBA6 and UBR4, was among the most significantly enriched genetic dependencies in cells with high aneuploidy scores—integer scores from 0 to 39 that are assigned to each of the cell lines based on the number of arm-level chromosomal gains and losses (refs. 66, 67; Fig. 7C; Supplementary Fig. S9F). Consistently, the group of cell lines with high aneuploidy scores (aneuploidy score ≥ 25, n = 107) was significantly more dependent on BIRC6 than the group of cell lines with low aneuploidy scores (aneuploidy score ≤ 6; n = 118; mean BIRC6 Chronos score = −0.406 and −0.158 for aneuploidy-high and -low groups, respectively, P = 2E-10; Fig. 7D). Similarly, the group of cell lines that is most strongly dependent on BIRC6 [bottom 100 in BIRC6 Chronos score (<−0.55)] exhibited significantly higher aneuploidy scores than the group of cell lines that is least dependent on BIRC6 [top 100 in BIRC6 Chronos score (>−0.091); mean aneuploidy score = 18.94 and 10.05 for BIRC6-dependent and -nondependent groups, respectively, P = 7E-13; Fig. 7E]. Together, these observations highlighted the strong association between the degree of aneuploidy and the dependency on BIRC6 and suggested the potential of using aneuploidy for identifying patients to be treated by the BIRC6 suppression strategy (Fig. 7F).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have focused on the role of BIRC6 in blocking the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis, a function that was attributed primarily to its BIR domain (33, 36, 68–71). In contrast, we found that the UBC domain of BIRC6 is essential for the fitness of a subset of carcinomas and also identified a previously unrecognized protein ubiquitination cascade regulated by this domain. Building on prior observations (30, 72), we also found that BIRC6 interacts with UBA6 and KCMF1. Together, these genetic and biochemical studies confirm that UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4 form a functional ubiquitin ligase complex and that the ubiquitin-related function of BIRC6 participates in the observed selective dependency on the BIRC6 module.

In exploring the biological function of this newly identified ubiquitin ligase complex, we found that the BIRC6 complex regulates the stability of HRI, a critical regulator of ISR. Specifically, using global proteomic profiling, we found that HRI is one of the most significantly upregulated proteins following BIRC6 depletion. In addition, in multiple cell lines that are dependent on these four genes encoding the components of the BIRC6 complex, depletion of any one of the genes upregulated HRI protein levels, without concomitantly increasing HRI mRNA levels. Moreover, HRI physically interacts with UBR4, a substrate-binding component (30) of this ubiquitin ligase complex and exhibited reduced ubiquitination as well as enhanced stability when this cascade was suppressed. Together, these observations identified the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex as a key regulator of HRI.

This ubiquitination cascade may control ISR-regulated translational homeostasis under both physiologic and pathologic conditions. Recent studies have highlighted the critical role of HRI in maintaining translational homeostasis under various stress conditions, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial stress, and cytosolic accumulation of misfolded proteins (73–76). However, despite the important role of HRI in triggering ISR in many different contexts, the molecular details of HRI regulation remain poorly understood. Our current work has now demonstrated the critical role of the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex in destabilizing HRI, which in turn is necessary for the survival of a subset of cancer cells. In these cancer cells, HRI-mediated, constitutive activation of the stress signaling pathways likely needs to be counteracted by BIRC6 complex–mediated HRI degradation (Fig. 7F).

It has been previously shown that due to the increased protein synthesis, tumor cells typically have elevated proteotoxic stress (77, 78). In addition, tumor cells are often exposed to stress stimuli driven by adverse microenvironmental conditions, which, together with increased proteotoxic stress, converge on the aberrant activation of the ISR. Consistently, increased stress granule formation, the direct outcome of ISR activation, has been observed in the samples of breast, lung, and kidney (73–76, 79, 80) cancers. In addition, the elevated expression of ATF4, the master transcriptional regulator of ISR, has been observed in the samples of esophageal and stomach cancers (81, 82). These observations reinforce and extend the notion that cancers require adaptations to tolerate increased cell stress, which represents a key hallmark of cancer (83). Moreover, given the irreversible cytotoxicity of prolonged ISR activation, the elevated basal activation of the ISR in tumors may represent a unique vulnerability of cancer. With these observations, we propose that the ISR signaling pathway is a promising target for cancer therapy with a potential broad applicability, much like other commonly targeted signaling pathways such as apoptosis and angiogenesis. Building on this notion, our study indicates that this unique vulnerability of cancer can be exploited via targeting the BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase complex. The highly selective nature of BIRC6 dependency and the specific role of BIRC6 in regulating ISR together nominate this ubiquitin ligase as an attractive oncology therapeutic target.

Our experimental and analytic pursuits for the predictive biomarkers of BIRC6 dependency have identified two candidates, baseline HRI activity and aneuploidy. Thus, consistent with our observation that BIRC6 regulates the stability, but not the activity, of HRI, the cell lines that were particularly sensitive to BIRC6 depletion appear to have higher baseline activity of HRI. However, the measurement of basal HRI activity within the tumor cells in the clinical setting remains a challenge. In addition, we found that BIRC6 is one of the most strongly enriched genetic dependencies in aneuploidy-high tumor cells. BIRC6 was not identified as a top hit in a similar analysis of the DepMap dataset to find genetic dependencies associated with aneuploidy (67), which could be accounted for, in part, by the use of different dependency datasets between the current study (CRISPR screen results) versus the study by Cohen-Sharir and colleagues (RNAi screen results; ref. 67). The currently identified connection between the BIRC6 complex and aneuploidy may offer a new path toward the therapeutic targeting of cancer cells with aneuploidy. Thus, imbalance in gene dosage in aneuploid cells inevitably triggers various stress types, including proteotoxic, metabolic, mitotic, and replication stress (84). Exploiting aneuploidy-associated stress phenotype in the tumor cells for the therapeutic benefit is an attractive concept (85, 86) but has not yet been operationalized. In light of our current observations, inhibiting the function of the BIRC6 complex and permitting aberrant activation of stress signaling may allow the selective targeting of the aneuploidy-associated stress phenotype.

More generally, this study provides an approach to identify new classes of nononcogene-driven cancer targets. Using dependency profiles derived from increasingly large sets of genome-scale screens now provides the means to identify these nononcogene dependencies. Indeed, we and others have previously used these approaches to identify protein complexes (14, 18), and the approach described here facilitates the discovery of pathways required for the survival of particular subsets of cancers. In addition, we also integrated genome engineering, genome-scale suppression screens, and proteomic profiling not only to identify a new ubiquitin ligase but also to decipher the mechanism by which this BIRC6 ubiquitin ligase regulates ISR and cell fitness. As such, this approach provides a robust path to identify and credential oncogenic pathways and targets while identifying the mechanisms that underlie these dependencies. Because several lines of evidence indicate that the number of these nononcogene targets far exceeds oncogene targets (87), we anticipate that this approach will open new avenues for cancer drug development.

METHODS

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Cell Culture.

All the parental cell lines were part of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and the DepMap (https://depmap.org), unless otherwise indicated. The sources of cell lines are ATCC, Asterand, German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Japanese Collection of Research Biosources, Korean Cell Line Bank, and RIKEN BioResource Center. The cell lines that express pLX-311-Cas9 were generated via Project Achilles (88). Mycoplasma testing was performed upon receiving cell lines and every 3 months of culture period thereafter using a Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (ABM, catalog no. G238). Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mmol/L glutamine, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 U/mL of streptomycin (Gibco, catalog no. 10378016), and 10% FBS (Sigma; all except for MCF10A) or in DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen, catalog no. 11330–032) supplemented with 5% horse serum (Invitrogen, catalog no. 16050–122), 20 ng/mL EGF, 0.5 mg/mL hydrocortisone, 100 ng/mL Cholera toxin, 10 μg/mL insulin, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 50 U/mL of streptomycin (for MCF10A) and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Orthotopic Xenograft Mouse Model.

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of either the Broad Institute (0194–01–18) or the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (04–101). IACUC guidelines on the ethical use and care of animals were observed. The engineered ZR751 cells were inoculated bilaterally into the mammary fat pads of 6- to 7-week-old NRG female mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. The engineered KYSE450 and HCC95 cells were inoculated bilaterally into the subcutaneous flanks of 6- to 8-week-old NSG female mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. When primary tumor volumes reached approximately 150 mm3, mice were assigned to either the doxycycline [DOX (−) and DOX (+)] groups (for ZR751) or the tamoxifen [TAM (−) and TAM (+)] groups (for KYSE450 and HCC95) so that the distribution of tumor volumes was comparable between these two groups.

Method Details

Genetic Dependency Data.

The genetic dependency data from the CRISPR screen used in this article were extracted from the 22Q2 public data release from the DepMap at the Broad Institute, consisting of dependency data for 17,386 genes across 1,086 cancer cell lines, and can be downloaded from the Figshare repository (https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/DepMap_22Q2_Public/19700056). These data were processed using the Chronos algorithm (29). The genetic dependency data from the RNAi screens were derived from Broad's Project Achilles (ref. 1; consisting of dependency data for 17,098 genes across 501 cancer cell lines), Novartis’ Project DRIVE (ref. 5; consisting of dependency data for 7,837 genes across 398 cancer cell lines), and the study by Marcotte and colleagues (ref. 89; consisting of dependency data for 16,056 genes across 77 breast cancer cell lines) and reprocessed using the DEMETER2 algorithm (90). The reprocessed RNAi data can be downloaded from https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/DEMETER_2_Combined_RNAi/9170975.

Genetic Dependency Analysis.

In Fig. 1E and Supplementary Figs. S1C and S2A, the mean Chronos score (mChronos) for the four genes constituting the BIRC6 module (UBA6, BIRC6, KCMF1, and UBR4) was calculated for each cell line. These cell lines were categorized into different classes based on the mChronos scores as follows: mChronos < −1 as “strongly dependent,” −1 ≤ mChronos < −0.75 as “intermediately dependent,” −0.75 ≤ mChronos < −0.5 as “weakly dependent,” and mChronos ≥ −0.5 as “resistant” in Supplementary Fig. S1C; mChronos < −1.62 as “BIRC6 module-dependent” and mChronos > −0.83 as “BIRC6 module-nondependent” in Supplementary Fig. S2A. In Figs. 2–6 and Supplementary Figs. S2–S9, cell lines were categorized into “BIRC6-dependent” and “BIRC6-nondependent” classes based on the following criteria: BIRC6 Chronos < −0.68 as “BIRC6 dependent” and BIRC6 Chronos > −0.4 as “BIRC6 nondependent.”

Subtype classification of breast cancer cell lines was conducted in accordance with the classification used in the DepMap 22Q2 public data release with following modifications: “Luminal” was renamed “ERpos”; “Basal A” and “Basal B” were both renamed “TNBC”; CAL148 cells were reclassified from “Luminal HER2Amp” to “TNBC” due to the low expression level of ESR1 and absence of ERBB2 amplification [ESR1 expression (log2(TPM + 1) = 0.043, ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 0.977]; COLO824 cells were classified as “TNBC” due to the low expression level of ESR1 and absence of ERBB2 amplification [ESR1 expression (log2(TPM + 1)) = 0.949, ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 0.956]; DU4475 cells were reclassified from “Luminal HER2Amp” to “TNBC” due to the low expression level of ESR1 and absence of ERBB2 amplification [ESR1 expression (log2(TPM + 1)) = 0.111, ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 0.998]; HCC1569 cells were reclassified from “Basal A” to “HER2Amp” due to the high level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 4.522]; HCC1954 cells were reclassified from “Basal A” to “HER2Amp” due to the high level of ERBB2 amplification (ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 3.582]; HCC2218 cells were reclassified from “Basal A” to “HER2Amp” due to the high level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 5.880]; MDA-MB-175VII cells were reclassified from “HER2Amp” to “ERpos” due to the high expression level of ESR1 [ESR1 expression (log2(TPM+1)) = 3.476] and the low level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 1.008]; MDA-MB-453 cells were reclassified from “HER2Amp” to “TNBC” due to the low level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 1.669]; MFM23 cells were reclassified from “Luminal” to “TNBC” due to the low expression level of ESR1 and absence of ERBB2 amplification [ESR1 expression (log2(TPM+1)) = 1.245, ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 0.929]; SUM185PE cells were reclassified from “Luminal” to “TNBC” due to the low expression level of ESR1 and absence of ERBB2 amplification [ESR1 expression (log2(TPM + 1)) = 0.111, ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 0.729]; HCC2218 cells were reclassified from “Basal A” to “HER2Amp” due to the high level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 5.061]; SUM225CWN cells were removed from the “Basal (TNBC)” class due to the absence of gene expression and copy-number data; SUM52PE cells were reclassified from “HER2Amp” to “ERpos” due to the low level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 0.729]; and UACC812 cells were reclassified from “Luminal” to “HER2Amp” due to the high level of ERBB2 amplification [ERBB2 copy number (log2(relative to ploidy + 1)) = 3.849].

Lentiviral Production.

Lentiviral production was conducted using HEK293T cells, as described on the Broad Institute Genetic Perturbation Platform (GPP) Web portal (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/). Briefly, the lentiviral particles were generated by the cotransfection of the lentiviral plasmid with a packaging (psPAX2; Addgene, catalog no. 12260) plasmid and VSV-G envelope (pMD2.G; Addgene, catalog no. 12259) into HEK293T cells using the TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus, catalog no. MIR2300) or PEIpro (Polyplus, catalog no. 101000033). The medium was replaced 8 hours after transfection, and the virus-containing medium was harvested after 36 to 48 hours.

sgRNAs.

The sgRNA sequences used for the validation experiments were designed using the Web-based program (sgRNA Designer) provided by the Broad Institute GPP (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/analysis-tools/sgrna-design). For the CRISPR-mediated gene knockout, annealed oligonucleotides carrying the sgRNA target sequence as well as the cloning adapters were inserted into either of the two guide RNA–expressing vectors pXPR_003 or pXPR_016, which also expresses a puromycin-resistance gene and a hygromycin-resistance gene, respectively. For the tamoxifen-inducible CRISPR knockout, annealed oligonucleotides encoding a cutting control (sgCh2-2), a positive control (sgSF3B1), or a BIRC6-targeting sgRNA (sgBIRC6-4) was inserted into the lentiviral Switch-ON vector (35), which enables the expression of sgRNA sequences following Cre-mediated excision of the poly-T sequence that was included within the sgRNA scaffold sequence. The targeting sequences for the individual sgRNAs are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

For the CRISPR interference (CRISPRi)–mediated gene silencing, we generated an all-in-one CRISPRi vector, named pXPR_023d, which expresses an sgRNA, a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused with a transcriptional repression domain (KRAB; KRAB-dCas9-HA), and a puromycin resistance gene. pXPR_023d was generated by replacing the Cas9-FLAG–encoding sequence in the pXPR_023 vector with the sequence encoding KRAB-dCas9-HA, which in turn was obtained from the pXPR_121 vector. Subsequently, annealed oligonucleotides carrying the sgRNA target sequence as well as the cloning adapters were inserted into the pXPR_023d vector. The target sequences for the individual sgRNAs are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

shRNAs.

The shRNA sequences targeting BIRC6 were selected from those used in Project Drive. For each of the BIRC6-targeting shRNA sequences, we also designed a seed-matched, nontargeting control sequence by replacing bases 11 to 13 of the shRNA-targeting sequence with their complement (34). Annealed oligonucleotides carrying the complementary shRNA target sequences, a loop sequence (GTTAATATTCATAGC), and the cloning adapters were inserted into pRSITEP-U6Tet-sh-EF1-TetRep-2A-Puro (Cellecta, catalog no. SVSHU6TEP-L) or pRSITEP-U6Tet-sh-EF1-TetRep-2A-Hygro, both of which enable doxycycline-inducible shRNA expression. The targeting sequences for the individual shRNAs are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Open Reading Frame Constructs.