Abstract

Municipal effluent is the largest reservoir of human enteric bacteria. Its public health significance, however, depends upon the physiological status of the wastewater bacterial community. A novel immunofluorescence assay was developed and used to examine the bacterial growth state during wastewater disinfection. Quantitative levels of three highly conserved cytosolic proteins (DnaK, Dps, and Fis) were determined by using enterobacterium-specific antibody fluorochrome-coupled probes. Enterobacterial Fis homologs were abundant in growing cells and nearly undetectable in stationary-phase cells. In contrast, enterobacterial Dps homologs were abundant in stationary-phase cells but virtually undetectable in growing cells. The range of variation in the abundance of both proteins was at least 100-fold as determined by Western blotting and immunofluorescence analysis. Enterobacterial DnaK homologs were nearly invariant with growth state, enabling their use as permeabilization controls. The cellular growth states of individual enterobacteria in wastewater samples were determined by measurement of Fis, Dps, and DnaK abundance (protein profiling). Intermediate levels of Fis and Dps were evident and occurred in response to physiological transitions. The results indicate that chlorination failed to kill coliforms but rather elicited nutrient starvation and a reversible nonculturable state. These studies suggest that the current standard procedures for wastewater analysis which rely on detection of culturable cells likely underestimate fecal coliform content.

Rivers and lakes beside most U.S. municipalities are categorized as recreational sites and are primary locations for municipal effluent discharge. Escherichia coli is monitored in such water as an indicator species for human fecal contamination and consequently is the primary measure of public health risk for communicable disease (5, 38). The Environmental Protection Agency requires that discharged municipal effluent contain no more than 4,000 fecal coliforms per liter (18). To meet these requirements, fecal coliform content usually is adjusted by chlorination with chlorine gas or chloramines, followed by residual chlorine neutralization with sulfur dioxide (53).

Since wastewater comprises a diverse community of microbial taxa, standard procedures for fecal coliform enumeration rely on selective enrichment techniques using detergent additives (18). However, studies on coliform regrowth in chlorinated drinking water indicate that such techniques significantly underestimate coliform death due to chlorine injury that induces a viable-but-nonculturable (VNC) state (14, 32, 33). Because resuscitation of injured cells can occur, it is well recognized that most standard procedures may underestimate the incidence of the indicator species and therefore distort water quality estimates (16, 43, 56). Established procedures for drinking water analysis have since been amended to address this concern (18).

Many factors which limit bacterial proliferation can precipitate the VNC state (36, 41). Reversible loss of culturability has been characterized in great detail in vibrios (44, 54) and is of particular importance in estimating the occurrence of cholera, a waterborne disease (15). In natural samples, the disparity between total and culturable cell counts and the diversity of 16S rRNA sequences apparent in uncultivated samples compared to culture collections indicate that most bacteria are unculturable (2, 7, 50). This suggests that the VNC state is widespread. Despite efforts to clarify the physiological basis for this state, the relationship between true metabolic dormancy and the VNC state remains unclear. In contrast, much has been learned about the early stationary phase (10, 22, 23) which precedes both the VNC state and metabolic dormancy. We suspected that similar issues might apply to coliforms in wastewater effluent after chlorination. To evaluate the VNC state, we developed a novel single-cell method to determine physiological status based on profiling of growth state-specific proteins.

To understand the physiological basis for chlorination-induced loss of culturability in wastewater coliforms, three cytosolic proteins were selected as targets for in situ analysis of uncultivated cells. This new method is called protein profiling and was used to differentiate growing (exponential-phase) from nongrowing or stationary-phase cells. DnaK (HSP70), a molecular chaperone (20, 31), plays a critical role in both exponential- and stationary-phase physiology (13, 45, 49). DnaK is a metabolically stable protein whose abundance changes only moderately in response to nutrient deprivation (47), permitting its use as a permeabilization control. Dps is a highly conserved 19-kDa DNA binding protein (1, 30) important in stationary-phase stress physiology (1, 30, 47). Dps abundance is inversely correlated with growth rate, and it varies in cellular concentration over 100-fold between the extremes of stationary phase and rapid growth (1, 30, 40, 47). Dps abundance was used as a positive indicator of nongrowth (e.g., starvation or stationary phase). Fis is an 11-kDa DNA binding protein (25, 26) which plays a critical role in coordinating rRNA synthesis with growth (39). Fis is therefore present in replicating cells, and its abundance is directly correlated with the growth rate (4, 52). Fis abundance varies over 500-fold between the extremes of rapid growth and stationary phase. Fis abundance was used as a positive indicator of growth. Results presented here include the development of the protein profiling method using wild-type and mutant populations of E. coli and its utility for studies on the major enteric bacterial genera. The protein profiling method was then used to study the physiological status of coliform bacteria in raw and chlorinated wastewater.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and cultivation.

The E. coli K-12 strains used were PBL500 (lacZ::Tn5 lacIq1) and PBL501 (ΔdnaK52::Cmr lacZ::Tn5 lacIq1) as described previously (45); PBL755 (Δfis::Tn10) and PBL664 (Δdps) were constructed as indicated later in this report, and DH5α [φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF) U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA69] was obtained from Gibco-BRL. Cell densities in both growing and starving cultures were monitored spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 600 nm. The media used were LB (34), m-T7 (Difco), m-Endo (BBL), Lauryl Tryptose broth (Difco), and EC broth (BBL). The medium used for Tets selections was prepared as described previously (11). Ampicillin and tetracycline were added at final concentrations of 100 and 12 μg/ml, respectively. Tests for chlorine injury of wastewater organisms were performed by spread plating of wastewater effluent dilutions with and without chlorination onto m-T7 or m-Endo agar plates in duplicate. Less than 1% variation was observed between replicate samples. Most probable numbers (MPNs) were determined as described previously (18). The bacterial community in raw wastewater samples was allowed to exhaust endogenous nutrients by continued incubation at ambient temperatures with gentle shaking in flasks until total cell numbers were observed to undergo no further increase.

Strain constructions.

Molecular biology methods were performed as described previously (8, 46). Analysis of DNA sequences was done as previously described (42). The fis mutant was constructed by phage M13-mediated recombination (9). A 2.1-kb HindIII fragment spanning fis from phage λ-529 (27) was ligated into the HindIII site of pACYC177 (New England Biolabs). The tet gene from pBR322 (Gibco-BRL) was subcloned as a 1.4-kb EcoRI-StyI fragment into pUC19 (New England Biolabs) at the EcoRI-XbaI sites and then subcloned again as a 1.7-kb PvuII fragment into the HpaI site at nucleotide 48 of fis. The region spanning the disrupted fis gene was subcloned as a 3.5-kb AgeI-NsiI fragment into the XmnI-PstI sites of M13mp9 (9). An additional 150 bp from the middle of the fis gene were deleted by BstEII digestion. M13mp9::Δfis::tet was then transformed into DH5α F′ Kanr (Gibco-BRL), and the resulting lysate was used to produce strain PB755 by homologous recombination. The dps mutant was constructed by transducing strain PBL500 with phage P1 (184593) (zbi-29::Tn10) (48), and Tets derivatives were recovered as previously described (11). Imprecise Tn10 excision deleted dps, as indicated by Western blot analysis and generation of chlorate resistance (24).

Source and treatment of wastewater samples.

Wastewater samples were obtained from a municipal treatment plant serving a population of 200,000. The wastewater in this facility is treated via an activated-sludge process, followed by disinfection by injection of chlorine gas, which is neutralized with sulfur dioxide gas before release. The initial chlorine concentration in the contact basin is 3.5 mg/liter and has a contact time of 1 h. Raw wastewater samples used in this study were taken from the effluent of the final or secondary clarifiers prior to chlorination. Chlorinated samples were collected from the effluent from the chlorine contact basin. One-liter volumes of secondary treated wastewater were shaken at 200 rpm at 25°C on a G-33 shaker (New Brunswick). Sodium hypochlorite was added to achieve 3.5 or 7 mg of available chlorine per liter, as indicated in Results. After 1 h, sodium thiosulfate was added (15 mg/liter) to neutralize the remaining free chlorine (18). Nutrient resupplementation was accomplished by addition of tryptone (0.1%, wt/vol) following neutralization.

Cloning, purification, and antibody production for Fis.

The fis gene was amplified by PCR using 5′-TTGAATTCATGTTCGAACAACGCG-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-TTCTTAAGAGCATTTAGCTAACC-3′ (reverse primer) from PBL500. The resulting PCR product was cloned into pUC19 following EcoRI digestion, placing fis under Plac control. A DH5α (Gibco-BRL) transformant was used for Fis purification as previously described (37). Boiling of cell lysates, followed by clarification by centrifugation at 200,000 × g for 3 h at 4°C, was used prior to ammonium sulfate precipation to facilitate protein removal. The resulting dialyzed material was fractionated by DNA cellulose chromatography as previously described for Dps (1) and purified to homogeneity by electroelution following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

Antibodies and synthesis of probes.

Preparation of antibodies was done as described previously (8, 28). Rabbit sera containing anti-DnaK, anti-Dps, and anti-Fis antibodies were processed with acetone powders from homologous mutant strains and then fractionated by immunoaffinity chromatography. The antibodies were further purified by affinity chromatography with protein A-Sepharose as described previously (28). Anti-DnaK antibodies were coupled to 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetic acid (AMCA X), anti-Dps antibodies were coupled to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and anti-Fis antibodies were coupled to Texas Red X in accordance with the manufacturer’s (Molecular Probes) protocols. The 16S rRNA probe specific for Enterobacteriaceae described previously (35), with the sequence 5′-CATGAATCACAAAGTGGTAAGCGCC-3′, was purchased prelabeled with fluorescein by the manufacturer (Gibco-BRL).

Microscopy sample preparation and probing procedures.

Cells were fixed by resuspension in phosphate-buffered saline, addition of 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde, and incubation at 4°C for 3 h with mixing. Washed cells were resuspended in equal parts phosphate-buffered saline and ethanol. Gelatin-subbed slides were prepared by dipping clean slides into a solution of 0.1% (wt/vol) gelatin and 0.01% (wt/vol) CrK(SO4)2 in deionized water and then air drying them at room temperature for 10 min. Fixed cells were applied to treated slides and dried at 37°C and dehydrated by successive rinses in 50, 80, and 98% ethanol. Cell permeabilization was accomplished by lysozyme-EDTA treatment (57) with lysozyme (5 mg/ml) in 100 mM Tris-HCl–50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Rinsed, dried slides were then simultaneously treated with all three probes in the dark and suspended in 2% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin–150 mM NaCl–100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) for 1 h in a humidified chamber. Slides were washed in 150 mM NaCl–100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5)–1% Triton X-100–1% deoxycholic acid–0.1% SDS for 10 min, rinsed in water, and dried at 37°C. Fluorochrome bleaching was minimized by phenylenediamine treatment (55) prior to application and sealing of the coverslip. Single-cell 16S rRNA analysis using the fluorescein-labeled oligodeoxynucleotide was done as previously described (21). Simultaneous use of antibody and nucleic acid probes employed the standard antibody probe procedure at 42°C. Specificity of the 16S rRNA probe was maintained in the absence of formamide. Fluorescence microscopy of raw and treated wastewater bacterial communities was performed in replicate by using samples obtained on different days from the wastewater processing facility. Variation in Fis and Dps cellular abundance observed during reconstruction experiments using raw wastewater followed similar trends despite the use of samples obtained on different days.

Micrograph analysis.

Fluorescence emission from the fluor-labeled antibody probes was detected by using a Microphot epifluorescence microscope (Nikon), an LEI-750 charge-coupled device camera (Leica), and Omega XF22, XF03, and XF43 filter sets for fluorescein, AMCA X, and Texas Red X, respectively. Images were captured, cells were counted, and fluorescence was quantitated by using Image-1 image analysis software (Universal Imaging). Fis, Dps, and DnaK levels were determined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the corresponding fluorochrome-labeled antibodies (FITC, Texas Red X, and AMCA X, respectively) for each of 1,000 cells per time point. Variation in individual cell permeability was minimized by normalizing Fis and Dps fluorescence to that for DnaK on a per-cell basis. Percentage of maximum cellular fluorescence was determined by assigning a value of 100% to the highest level of fluorescence of the normalized Fis-FITC label and the normalized Dps-Texas Red X label. All remaining values were divided by that value and multiplied by 100 to calculate the percentage of maximum cellular fluorescence.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Prior to electrophoresis, samples were adjusted to 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8)–2% SDS–0.75 M 2-mercaptoethanol–10% glycerol–20 μg of bromophenyl blue per ml and boiled for 10 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE with 4% (wt/vol) acrylamide stacking and 16% (wt/vol) acrylamide separating gels as described previously (45, 47), with prestained molecular mass markers (Novex). Western blots were prepared essentially as described previously (47). Western blots were probed with a 1:1,000 dilution of the rabbit sera and then a 1:1,000 dilution of sheep anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Gibco-BRL). Western blots were processed and developed with the ECL reagent system in accordance with the manufacturer’s (Amersham) protocol. Chemiluminescence was detected by exposing Kodak XAR film. Protein abundance was determined by comparison to purified standards as previously described (47).

Phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis (distance) of 16S rRNA sequences from selected proteobacteria was performed with PHYLIP 3.57c (19) to examine the generality of the 16S rRNA probe specific for Enterobacteriaceae (35). A 906-nucleotide region spanning positions 496 to 1502 of the E. coli rRNA gene was used to prepare a sequence alignment. The following sequences were used to construct the tree: CCRRRNAC (Caulobacter crescentus), BSUB16SR (Bacillus subtilis), D88008 (Alcaligenes faecalis), X06684 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), AC16SRD (Acinetobacter calcoaceticus), EA16SRR (Erwinia amylovora), M59160 (Serratia marcescens), HAFRR16SA (Hafnia alvei), YEN16SA (Yersinia enterocolitica), RAATCR (Rahnella aquatilis), X07652 (Proteus vulgaris), D78009 (Xenorhabdus nematophilus), KCRRNA16S (Kluyvera cryocrescens), M59291 (Citrobacter freundii), AB004750 (Enterobacter aerogenes), U33121 (Klebsiella pneumoniae), AB004754 (Klebsiella oxytoca), ST16SRD (Salmonella typhimurium), SF16SRD (Shigella flexneri), and I10328 (E. coli). A multiple-sequence alignment was made with CLUSTAL W (51). SEQBOOT was used to generate 100 bootstrapped data sets. Distance matrices were calculated with DNADIST using the default options. One hundred unrooted trees were inferred by neighbor-joining analysis of the distance matrix data by using NEIGHBOR. Bias introduced by the order of sequence addition was minimized by randomizing the input order. The most frequent branching order was determined with CONSENSE.

RESULTS

Chlorine injury of coliforms in wastewater.

The occurrence of chlorine injury of coliforms in chlorinated wastewater was determined as previously described for drinking water (14, 32, 33). Municipal wastewater chlorination reduced the number of CFU on selective medium (m-Endo) by nearly 100-fold relative to an untreated sample (4.92 × 103 versus 5.02 × 105 CFU/ml). In contrast, no reduction in plating efficiency was observed when a medium (m-T7) designed to recover chlorine-injured coliforms (5.30 × 105 CFU/ml) was used. Similar results were obtained with wastewater samples obtained on different days. These results indicate that the loss of culturability observed when selective growth conditions are used results from the induction of a nonculturable state by chlorination.

Protein profiling for single-cell physiological status.

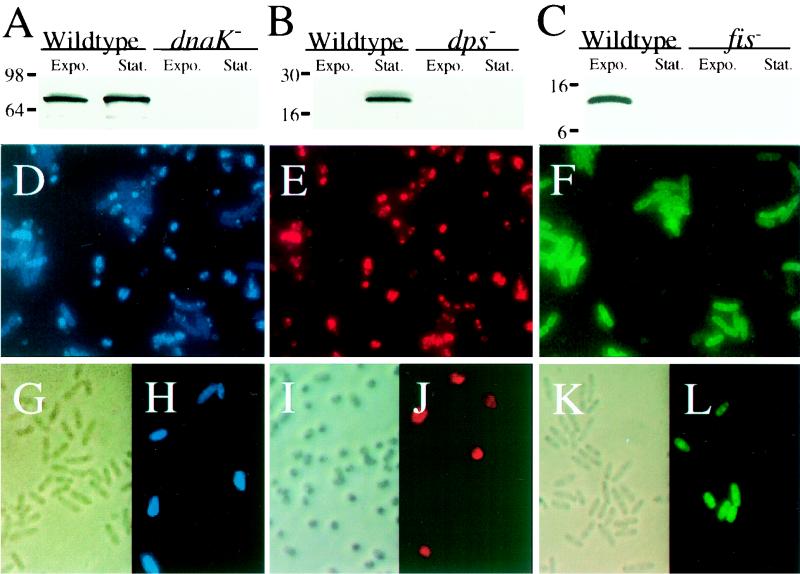

Target protein abundance in E. coli populations during growth and starvation initially was determined by Western blot analysis using DnaK, Fis, and Dps antibodies (Fig. 1A to C, lanes 1 and 2). Antibody specificity was verified by the absence of cross-reacting material in extracts of mutants lacking the structural genes for the target proteins (Fig. 1A to C, lanes 3 and 4). Single-cell protein profiles then were determined by simultaneously probing a mixed population of growing and starving wild-type E. coli bacteria with all three antibodies individually coupled to distinct fluorochromes. Examination of individual fields at each of three wavelengths revealed the identities of growing and starving cells (Fig. 1D to F). All cells could be observed by using the DnaK probe (Fig. 1D). Starving cells only had high levels of Dps (Fig. 1E), while growing cells only had high levels of Fis (Fig. 1F). Fluorescent-antibody probe specificity was confirmed by using mixed populations of wild-type and mutant E. coli strains for each of the target proteins (Fig. 1G to L).

FIG. 1.

Growth state and target protein specificity of antibody probes. Western blots of various cell extracts of growing (exponential phase [Expo.]) and starving (stationary phase [Stat.]) wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) and mutant (lanes 3 and 4) E. coli strains were visualized by chemiluminescence (A to C). Molecular mass standards (kilodaltons) are indicated at the left of each panel. Single-exposure fluorescence micrographs show growing and starving wild-type E. coli cells mixed at a 1:1 ratio, probed with the three fluorochrome-labeled antibody probes, and visualized by using fluor-specific filters. Shown are AMCA X-labeled anti-DnaK (D), Texas Red X-labeled anti-Dps (E), and FITC-labeled anti-Fis (F) antibodies. Bright-field and single-exposure fluorescence micrographs show wild-type and mutant E. coli cells mixed at a 1:5 ratio and probed with AMCA X-labeled anti-DnaK antibody (G and H), Texas Red X-labeled anti-Dps antibody (I and J), and FITC-labeled anti-Fis antibody (K and L). The left panel in each set (G to L) is a phase-contrast bright-field image of the same field viewed by fluorescence in the right panel.

Phylogenetic specificity of the protein profiling method.

Wastewater bacterial communities are comprised of many taxa, although Enterobacteriaceae or coliforms are of primary importance (29). It was therefore necessary to evaluate the phylogenetic specificity of the antibody probes to discriminate between the percentage of coliform species detectable in wastewater samples relative to the detection frequency of noncoliform species. Western blot analysis of pure cultures of selected species indicated that all major enterobacterial genera contained the target proteins and that their synthesis was regulated as observed in E. coli (Fig. 2A and data not shown). P. aeruginosa, a common wastewater inhabitant (3), was used as a noncoliform control. A DnaK homolog was detected in this organism (Fig. 2A) (28), but Dps and Fis were not evident. These results indicated that the method effectively detected coliforms. To preclude enumeration of noncoliform species, only DnaK-containing cells which exhibited detectable levels of either Dps or Fis were scored in subsequent studies.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic range of antibody probes. Western blots of cell extracts of growing (E) and starving (S) wild-type Enterobacteriaceae and a member of the gamma subdivision of the subclass Proteobacteria probed with anti-Fis, anti-Dps, or anti-DnaK antibodies were visualized by chemiluminescence (A). Single-cell detection was done by using an FITC-labeled 16S rRNA probe specific for Enterobacteriaceae (+, −). Bright-field (B1) and single-exposure fluorescence (B2 and B3) micrographs of the same field of cells from raw wastewater probed simultaneously with AMCA X-labeled anti-DnaK antibody (B2) and an FITC-labeled 16S rRNA probe (B3) are shown. Representative cells nonfluorescent with either probe are indicated by arrows. Abbreviations for species used: E. c., E. coli; K. p., K. pneumoniae; E. a., E. aerogenes; C. f., C. freundii; P. v., P. vulgaris; S. m., S. marcescens; P. a., P. aeruginosa.

A 16S rRNA probe specific for Enterobacteriaceae (35) was employed to further test the specificity of the antibody probes by using pure cultures (Fig. 2A). The utility of the 16S rRNA probe for detection of a more comprehensive set of Enterobacteriaceae than described previously (35) was first verified by phylogenetic analysis and indicated that the probe sequence was complementary to all of the 16S rRNA sequences of the major genera of Enterobacteriaceae. Raw wastewater samples analyzed by simultaneous probing with the AMCA X-coupled DnaK antibody and fluorescein-coupled 16S rRNA oligonucleotide exhibited nearly complete (99.75%) overlap of cells detected by the two probes (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that noncoliform taxa did not interfere with coliform detection in these studies. These results also demonstrate compatibility between nucleic acid hybridization for taxon identification and protein profiling for physiological analysis.

Protein profiling of uncultivated bacteria.

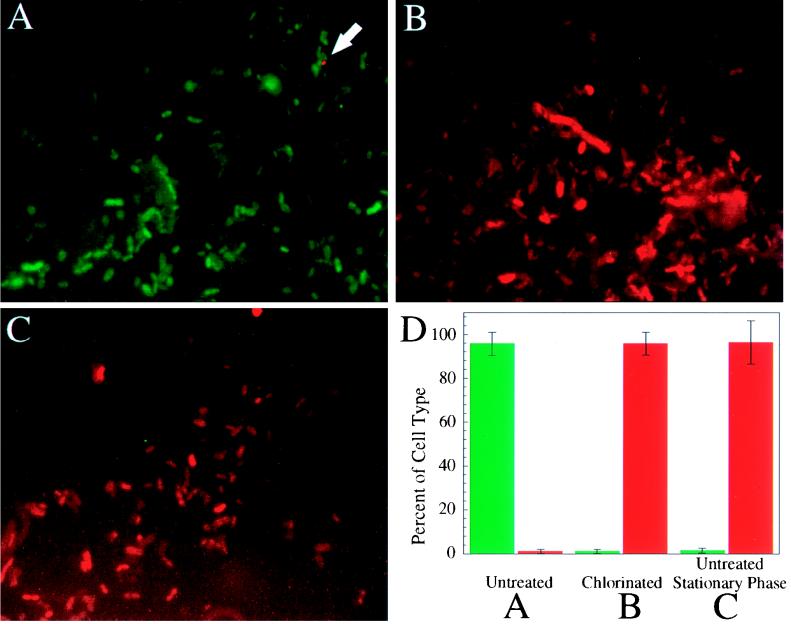

The protein profiling procedure was then applied to studies of uncultivated coliforms in chlorinated and raw wastewater. Raw, untreated samples were analyzed by using the fluor-labeled antibody probes applied simultaneously. These samples were found to consist primarily of Fis-containing cells which were nearly devoid of Dps (Fig. 3A). Only a few cells in such samples contained detectable levels of Dps (Fig. 3A, arrow). The images shown in Fig. 3A to C are composites of FITC and Texas Red X emission. There was good concordance in this sample between cells found to contain Fis and those containing DnaK (data not shown). In contrast, chlorinated samples consisted primarily of Dps-containing cells with nearly undetectable levels of Fis (Fig. 3B). Again, all Dps-containing cells also contained DnaK (data not shown). Surprisingly, cells from raw water samples which had been allowed to enter stationary phase by continued incubation at ambient temperatures also exhibited the high-Dps and low-Fis protein profile (Fig. 3C). Because of the similarity between chlorinated samples and untreated samples which had been allowed to enter stationary phase, it was unclear whether this protein profile was the result of oxidation or starvation. To understand which stimulus was responsible, wastewater chlorination was tested for its effects on the growth of newly inoculated cells. A raw wastewater sample and a chlorinated (neutralized) derivative sample were sterilized by filtration and inoculated with growing wild-type E. coli. No growth was observed in the treated water after 3 days of incubation. In the untreated water, however, growth (g = 3 h) and a high cell yield (5.26 × 108 CFU/ml) was observed. This indicates that there were insufficient nutrients to support bacterial growth and therefore that the preponderance of Dps-containing cells in chlorinated wastewater results from conditions of starvation.

FIG. 3.

Growth state of coliform bacteria in chlorinated and raw wastewater. Fluorescence micrographs show wastewater samples probed with the three fluor-labeled antibody probes. Panels: A, raw sample; C, raw stationary-phase sample; B, chlorinated sample. Double exposures are shown which combine images of FITC (anti-Fis)- and Texas Red X (anti-Dps)-probed samples. Quantitation of numbers of cells with detectable Dps or Fis as percentages of the total number of cells examined is shown in panel D. Bars: green, Fis-containing cells; red, Dps-containing cells. Error bars indicate the variation observed for each cell type observed among three fields of view; approximately 400 cells were examined for each condition. The arrow in panel A indicates the location of a rare Dps-containing cell in untreated wastewater.

Resuscitation of coliforms in treated wastewater.

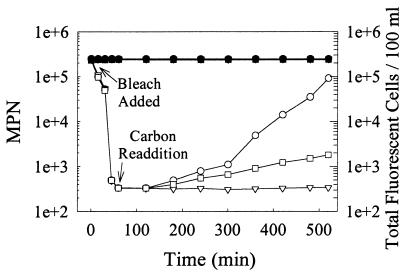

To test the possibility that chlorinated wastewater might be nutrient deficient, raw wastewater samples were chlorinated and then supplemented with nutrients (Fig. 4). Standard chlorination (3.5 mg/liter, 1 h) resulted in an initial 1,000-fold reduction in coliform content as determined by MPN analysis. Without nutrient supplementation, no subsequent change in MPNs was observed despite prolonged incubation at ambient temperatures (Fig. 4, inverted triangles). However, in supplemented cultures, culturability reached pretreatment levels within a 9-h incubation period (Fig. 4, circles). If the increase in culturable fecal coliforms observed after standard chlorine treatment resulted from the growth of a small surviving subpopulation, it would necessitate that such cells divide with a 54-min doubling time at 24°C and initiate division without a lag. Since the measured growth rate of endogenous cells in raw water samples was 150 min, rapid regrowth of a subpopulation appears improbable. Instead, the supplementation-induced increase in MPNs more likely results from resuscitation of dormant cells. The rate of increase in MPNs in supplemented cultures was inversely proportional to the degree of chlorination; a doubling of the chlorine concentration from 3.5 to 7.0 mg/liter greatly reduced the rate of increase in the appearance of culturable cells (Fig. 4, squares). In this latter case, the rate of increase in MPNs was consistent with the regrowth of a subpopulation of surviving cells.

FIG. 4.

Coliform regrowth and protein profiling in chlorinated wastewater. MPNs (open symbols) and DnaK-containing total fluorescent cell counts (closed symbols) of chlorine-treated (3.5 [○, ▿, ●, ▾] or 7 [□, ■] mg/liter) wastewater samples with nutrient supplementation (0.1% [wt/vol] tryptone; ○, ●, □, ■) and without additions (▿, ▾) are shown. MPNs were determined by using EC broth. Total fluorescent (DnaK-containing)-cell counts were determined by using samples with and without nutrient supplementation.

Single-cell protein profiling distinguishes resuscitation from regrowth.

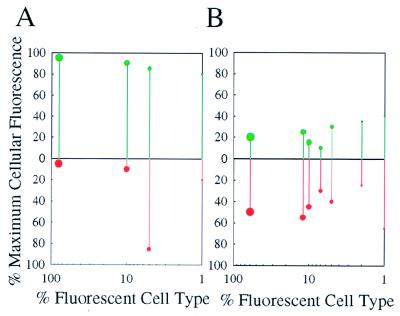

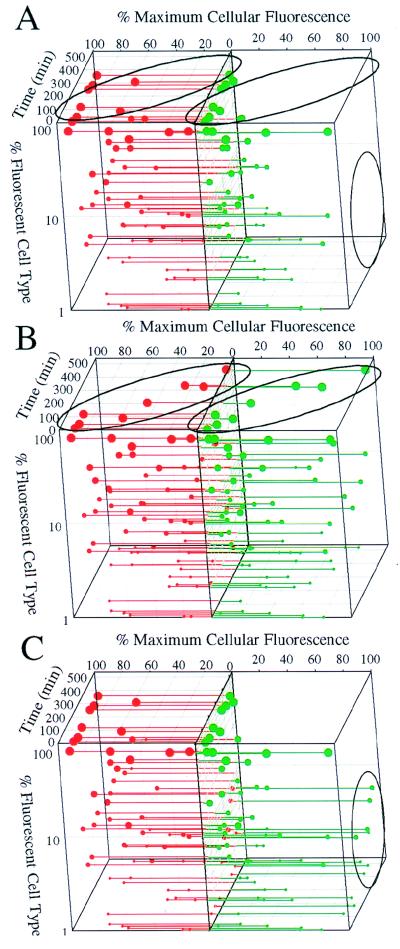

The inability to distinguish between resuscitation of viable but otherwise nonculturable cells rather than regrowth of surviving subpopulations lies at the heart of much recent controversy concerning the VNC state (6, 12, 17). To resolve this issue in the present case, the fluor-labeled antibody probes were used to quantify the growth state of individual cells by protein profiling in response to chlorination and nutrient supplementation. A raw wastewater sample was chlorinated for 1 h, neutralized, and monitored for an additional 8 h. The quantities of Fis (green) and Dps (red) in 1,000 cells were then examined at selected time intervals. The results obtained at the beginning of the experiment and 60 min following chlorination are shown in Fig. 5. The results obtained for the entire experiment are presented in Fig. 6A. Fis and Dps cellular abundances were determined by normalizing protein-specific fluorescence intensity on an individual-cell basis to the amount of DnaK detected in the same cell. This minimized the variation resulting from differential cell permeability to the antibody probes. These values are presented as percentages of the maximum cellular fluorescence observed for all cells. Numbers of cells with specific Fis and Dps contents were then summed into groups comprising 5% incremental amounts of either protein, and the relative abundance of cells in these groups is shown as a percentage of the total number of fluorescent cells. Upon chlorine addition (Fig. 5 and 6A), there was a rapid reduction in the number of cells containing Fis and the quantity of Fis in these cells. These changes were largely complete within the treatment time (1 h) and prior to chlorine neutralization. A concomitant increase in the number of Dps-containing cells and the quantity of Dps per cell was also observed. During this period, there was no change in the total number of fluorescent cells (Fig. 4, closed symbols), thus eliminating lysis as a contributing factor.

FIG. 5.

Quantitative analysis of cellular Fis and Dps contents and abundances of cell types following treatment of raw wastewater by chlorination. Samples were examined immediately before (A) or 60 min after (B) treatment. Cellular contents of Fis (green balls and lines, upper panel) and Dps (red balls and lines, lower panel) are indicated as percentages of the maximum cellular fluorescence of the brightest cell in each sample (y axis). Lines extending from above to below the midpoint line indicate Fis and Dps contents, respectively, of the same individuals. The abundances of cells exhibiting particular degrees of fluorescence are shown as percentages of fluorescent cell type (x axis). Ball size is proportional to the abundance of that fluorescent cell group using four sizes: large, 100 to 50%; medium, 50 to 10%; small, 10 to 3%; smallest, 3% to undetectable. Cells are grouped into clusters based on 5% increments of individual cellular fluorescence.

FIG. 6.

Quantitative analysis of single-cell Fis and Dps contents and abundance of cell types. Samples were chlorine treated (A and B, 3.5 mg of chlorine per liter; C, 7 mg/liter) and either not resupplemented with nutrients (A) or nutrient resupplemented (B and C). The data are presented as indicated in the legend to Fig. 5 with the added dimension of experimental time (z axis) and 90° rotation of the figure relative to the previous figure. Changes in Fis and Dps protein profiles indicating resuscitation (A and B, ovals) and subpopulation regrowth (A and C, circles) are indicated. Similar trends in the cellular concentrations of Fis and Dps were observed in replicate trials. One thousand cells were examined for each sample time point.

The response of individual cells to nutrient supplementation following chlorine treatment (3.5 mg/liter) and neutralization was also examined (Fig. 6B). The initial response to chlorination was as observed previously (Fig. 6A). However, 2 h after nutrient addition, an increasing fraction of fluorescent cells changed their protein profile (Fig. 6A and B, ovals). Dps-containing cells and the quantity of Dps per cell decreased, while Fis-containing cells and the quantity of Fis per cell increased. After about 9 h, this change was complete and the protein profile of nearly all of the cells closely resembled that of cells in raw wastewater. The absence of a significant number of residual Dps-containing cells present during this recovery eliminates the hypothesis of subpopulation regrowth by rare surviving cells. Instead, the results indicate that the bulk of the cell community was starving and was resuscitated by nutrient supplementation.

Nutrient supplementation of wastewater samples subjected to increased chlorination (7 mg/liter, 1 h) resulted in a much slower increase in culturable fecal coliforms (Fig. 4). To test if this might result from the regrowth of a subpopulation of surviving cells, cell protein profiles were determined (Fig. 6C). As seen previously (Fig. 6B), 2 h after nutrient supplementation, a change in the protein content of a small number of cells became evident, in which Fis abundance increased while Dps abundance decreased (Fig. 6A and C, circles). However, the rate of increase of such cells was much slower than observed previously. The abundance of this class of fluorescent cells agreed closely with the MPNs after similar treatment (Fig. 4) and represented only a fraction of 1% of the total fluorescent cells. Such cells may represent rare survivors resulting from the increased level of chlorination which, as a result of continued chlorine injury, grow at a reduced rate.

DISCUSSION

These results indicate that standard chlorination of municipal wastewater may often result in nutrient deprivation and loss of coliform culturability rather than lethality. Utilization of selective growth conditions precludes the ability of such cells to regain culturability. However, nutrient addition and subsequent incubation allow the resuscitation of nearly 100% of the initial coliform community. The suggested holding time prior to wastewater analysis is 6 h, and holding times can be extended to a maximum of 24 h (18). Discharged wastewater is, however, not held for any time, and the exposure of the treated cell community to nutrients present in recreational water supplies, as well as the absence of selective growth conditions, may well result in significant levels of resuscitation of the coliform community. Such cells could represent a previously unrecognized reservoir of organisms with significant public health implications. We suspect that standard procedures in current use induce the VNC state and therefore are responsible for the release of large populations of viable and potentially culturable coliforms into recreational water.

Single-cell quantitation of Fis, Dps, and DnaK levels was used as a means of assessing physiological growth status. To our knowledge, this is the first study employing cytosolic protein targets for such a purpose. Since the method was compatible with the simultaneous use of a 16S rRNA-derived oligodeoxynucleotide probe, it would be feasible to determine if the apparent variation in protein profile exhibited at the single-cell level might result from taxon-specific differences in response to chlorination. Such information could be useful for improving our understanding of wastewater treatment processes. In addition, the wide range of variation in cellular concentrations of Fis and Dps corresponding to changes in growth state provide a highly sensitive measure of bacterial physiological status. The occurrence of the nongrowth state is accompanied by an increase in signal production (Dps), which represents a fundamental difference from techniques which, instead, use 16S rRNA as a measure of physiological status. The cellular concentration of 16S rRNA varies only two- to threefold with the growth state, and 16S rRNA typically decreases in abundance with entry of the cell into the nongrowth state.

The protein profiling method was effective with uncultivated cells derived from raw and treated wastewater. The ability to examine and derive single-cell physiological information without resorting to cultivation or incubation techniques provides a new opportunity to obtain a real-time picture of bacterial physiology. As such, this method may be useful for other studies in which the physiological status of uncultivated bacteria is of interest. Current efforts concern the application of this method to studies on pure-culture physiological heterogeneity during the stationary phase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank T. J. Morris for helpful comments and R. Morita and S. Giovannoni for encouragement.

This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Energy (DE-FG02-93ER61701).

REFERENCES

- 1.Almiron M, Link A J, Furlong D, Kolter R. A novel DNA-binding protein with regulatory and protective roles in starved Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2646–2654. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahlaoui M A, Baleux B, Troussellier M. Dynamics of pollution-indicator and pathogenic bacteria in high-rate oxidation wastewater treatment ponds. Water Res. 1997;31:630–638. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ball C A, Osuna R, Ferguson K C, Johnson R C. Dramatic changes in Fis levels upon nutrient upshift in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8043–8056. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8043-8056.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballentine R K, Dufour A P. Ambient water quality criteria for bacteria. Publication 440/5-84-001. Washington, D.C: Environmental Protection Agency; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barer M R. Viable but non-culturable and dormant bacteria: time to resolve an oxymoron and a misnomer. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:629–631. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-8-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barns S M, Fundyga R B, Jeffries M W, Pace N R. Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1609–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blum P, Ory J, Bauernfeind J, Krska J. Physiological consequences of DnaK and DnaJ overproduction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7436–7444. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7436-7444.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum P, Holzschu D, Kwan H, Riggs D, Artz S W. Gene replacement and retrieval with recombinant M13mp bacteriophages. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:538–546. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.538-546.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blum P H. Molecular genetics of the bacterial stationary phase. In: Morita R, editor. Bacteria in the oligotrophic environment, with special emphasis on starvation survival. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1997. pp. 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bochner B R, Huang H-C, Schieven G L, Ames B N. Positive selection for loss of tetracycline resistance. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:926–933. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.926-933.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogosian G, Morris P J L, O’Neil J P. A mixed culture recovery method indicates that enteric bacteria do not enter the viable but nonculturable state. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1736–1742. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1736-1742.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bukau B, Walker G C. Deletion ΔdnaK52 mutants of Escherichia coli have defects in chromosome segregation and plasmid maintenance at normal growth temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:6030–6038. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6030-6038.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camper A K, McFeters G A. Chlorine injury and the enumeration of waterborne coliform bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:633–641. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.3.633-641.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colwell R R. Global climate and infectious disease: the cholera paradigm. Science. 1996;274:2025–2031. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawe L L, Penrose W R. “Bactericidal” property of seawater: death or debilitation? Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:829–833. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.5.829-833.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dodd C E R, Sharman R L, Bloomfield S F, Booth I R, Stewart G S A B. Inimical processes: bacterial self-destruction and sub-lethal injury. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1997;8:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaton A D, Clesceri L S, Greenberg A E, editors. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 19th ed. Washington, D.C: American Public Health Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny interface package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgopoulos C. The emergence of the chaperone machines. Trends Biochem Genet. 1992;17:295–299. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90439-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannoni S J, DeLong E F, Olsen G J, Pace N R. Phylogenetic group-specific oligodeoxynucleotide probes for identification of single microbial cells. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:720–726. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.720-726.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodrich-Blair H, Uria-Nickelsen M, Kolter R. Regulation of gene expression in stationary phase. In: Lin E C C, Simon Lynch A, editors. Regulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1996. pp. 571–583. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hengge-Aronis R. Regulation of gene expression during entry into stationary phase. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtis III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1497–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson M E, Rajagopalan K V. Involvement of chlA, E, M, and N loci in Escherichia coli molybdopterin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:117–125. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.117-125.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson R C, Ball C A, Pfeffer D, Simon M I. Isolation of the gene encoding the Hin recombinational enhancer binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3484–3488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch C, Vandekerckhove J, Kahmann R. Escherichia coli host factor for site-specific DNA inversion: cloning and characterization of the fis gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4237–4241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohara Y, Akiyama K, Isono K. The physical map of the whole E. coli chromosome: application of a new strategy for rapid analysis and sorting of a large genomic library. Cell. 1987;50:495–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krska J, Elthon T, Blum P. Monoclonal antibody recognition and function of a DnaK (HSP70) epitope found in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6433–6440. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6433-6440.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeChevallier M W, Seidler R J, Evans T M. Enumeration and characterization of standard plate count bacteria in chlorinated and raw water supplies. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:922–930. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.5.922-930.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lomovskaya O L, Kidwell J P, Matin A. Characterization of the ς38-dependent expression of a core Escherichia coli starvation gene, pexB. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3928–3935. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.3928-3935.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayhew M, Hartl F-U. Molecular chaperone proteins. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtis III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 922–937. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFeters G A, Kippin J S, LeChevallier M W. Injured coliforms in drinking water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:1–5. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.1.1-5.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McFeters G A. Enumeration, occurrence, and significance of injured indicator bacteria in drinking water. In: McFeters G A, editor. Drinking water microbiology. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 478–492. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittelman M W, Habash M, Lacroix J M, Khoury A E, Krajden M. Rapid detection of Enterobacteriaceae in urine by fluorescent 16S rRNA in situ hybridization on membrane filters. J Microbiol Methods. 1997;30:153–160. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morita R Y. Bacteria in oligotrophic environments. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nash H A, Robertson C A. Purification and properties of the Escherichia coli protein factor required for λ integrative recombination. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:9246–9253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Technical Advisory Committee. Water quality criteria. Washington, D.C: Federal Water Pollution Control Administration; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilsson L, Verbeek H, Vijgenboom E, van Drunen C, Vanet A, Bosch L. FIS-dependent trans activation of stable RNA operons of Escherichia coli under various growth conditions. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:921–929. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.3.921-929.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Notley L, Ferenci T. Induction of RpoS-dependent functions in glucose-limited continuous culture: what level of nutrient limitation induces the stationary phase of Escherichia coli? J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1465–1468. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1465-1468.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliver J D. Formation of viable but nonculturable cells. In: Kellogg S, editor. Starvation in bacteria. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 239–272. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Partridge J, King J, Krska J, Rockabrand D, Blum P. Cloning, heterologous expression, and characterization of the Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae DnaK protein. Infect Immun. 1993;61:411–417. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.2.411-417.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Postgate J R, Hunter J R. The survival of starved bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1962;26:1–18. doi: 10.1099/00221287-29-2-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravel L, Knight I T, Monahan C E, Hill R T, Colwell R R. Temperature-induced recovery of Vibrio cholerae from the viable but nonculturable state: growth or resuscitation? Microbiology. 1995;141:377–383. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-2-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rockabrand D, Arthur T, Korinek G, Livers K, Blum P. An essential role for the Escherichia coli DnaK protein in starvation-induced thermotolerance, H2O2 resistance, and reductive division. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3695–3703. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3695-3703.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rockabrand D, Blum P. Multicopy plasmid suppression of stationary phase chaperone toxicity in Escherichia coli by phosphogluconate dehydratase and the N-terminus of DnaK. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;249:498–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00290575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rockabrand D, Livers K, Austin T, Kaiser R, Jensen D, Burgess R, Blum P. Roles of DnaK and RpoS in starvation-induced thermotolerance of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:846–854. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.846-854.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singer M, Baker T A, Schnitzler G, Deischel S M, Goel M, Dove W, Jaacks K J, Grossman A D, Erickson J W, Gross C A. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:1–24. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.1-24.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spence J, Cegielska A, Georgopolous C. Role of Escherichia coli heat shock proteins DnaK and HtpG (C62.5) in response to nutritional deprivation. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7157–7166. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7157-7166.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staley J T, Konopka A. Measurement of in situ activities of nonphotosynthetic microorganisms in aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1985;39:1379–1384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson J F, Moitoso de Vargas L, Kock D, Kahmann R, Landy A. Cellular factors couple recombination with growth phase: characterization of a new component in the λ site-specific recombination pathway. Cell. 1987;50:901–908. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. National pollutant discharge elimination system permit application requirements for publicly owned treatment works and other treatment works treating domestic sewage. Fed Regist. 1995;60:62562–62569. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitesides M D, Oliver J D. Resuscitation of Vibrio vulnificus from the viable but nonculturable state. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;60:3284–3291. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1002-1005.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolosewick J J. Cell fine structure and protein antigenicity after polyethylene glycol processing. In: Revel J-P, Barnard T, Haggis G H, editors. The science of biological specimen preparation. AMF O’Hare, Ill: SEM Inc.; 1984. pp. 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu J-S, Roberts N, Singleton F L, Atwell R W, Grimes D J, Colwell R R. Survival and viability of nonculturable Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae in the estuarine and marine environment. Microb Ecol. 1982;8:313–323. doi: 10.1007/BF02010671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zarda B, Amann R, Wallner G, Schleifer K-H. Identification of single bacterial cells using digoxigenin-labelled rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2823–2830. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-12-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]