Abstract

Crown gall caused by Agrobacterium is one of the predominant diseases encountered in rose cultures. However, our current knowledge of the bacterial strains that invade rose plants and the way in which they spread is limited. Here, we describe the integrated physiological and molecular analyses of 30 Agrobacterium isolates obtained from crown gall tumors and of several reference strains. Characterization was based on the determination of the biovar, analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms by PCR (PCR-RFLP), elucidation of the opine type, and PCR-RFLP analysis of genes involved in virulence and oncogenesis. This study led to the classification of rose isolates into seven groups with common chromosome characteristics and seven groups with common Ti plasmid characteristics. Altogether, the rose isolates formed 14 independent groups, with no specific association of plasmid- and chromosome-encoded traits. The predominant Ti plasmid characteristic was that 16 of the isolates induced the production of the uncommon opine succinamopine, while the other 14 were nopaline-producing isolates. With the exception of one, all succinamopine Ti plasmids belonged to the same plasmid group. Conversely, the nopaline Ti plasmids belonged to five groups, one of these containing seven isolates. We showed that outbreaks of disease provoked by the succinamopine-producing isolates in different countries and nurseries concurred with a common origin of specific rootstock clones. Similarly, groups of nopaline-producing isolates were associated with particular rootstock clones. These results strongly suggest that the causal agent of crown gall disease in rose plants is transmitted via rootstock material.

The soilborne, gram-negative bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens infects dicotyledonous plants from almost 100 different families, causing crown gall disease throughout the world (11). This disease is characterized by the formation of tumors at wound sites, an event resulting from a natural interkingdom DNA transfer. Approximately 15 genes from a 200-kb tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid of the bacterium are transferred to the plant cells, where they become integrated into the host genome (7; for reviews, see references 10, 22, and 42) and expressed. The transfer requires both the products of other genes located in the nontransferred virulence (vir) region of the Ti plasmid and proteins that are encoded by the chromosome (4). The transferred DNA (T-DNA) portion of the Ti plasmid carries the genes tms and tmr, which encode proteins involved in the synthesis of the plant hormones auxin and cytokinin, respectively, which are responsible for uncontrolled cell proliferation during crown gall tumorigenesis (23, 26, 29). The T-DNA also encodes enzymes used for the synthesis of tumor-specific compounds, called opines. Opines are released by the plant and can be used by the bacterium as the sole carbon and/or nitrogen sources (14) and perceived as signals for the conjugal transfer of the Ti plasmid between strains of Agrobacterium (1, 32, 43). The opines are mostly amino acid or sugar derivatives. The metabolism of opines is encoded by nontransferred genes on the Ti plasmid (17). The presence of the opine molecules in crown galls therefore provides an ecological niche favoring pathogen development and Ti plasmid dissemination (2).

The extent of crown gall disease depends largely on the physiological conditions of the host plants. When the plants are in a good state of health, tumors are limited and do not influence the viability of the hosts. In contrast, the disease becomes severe when preinfections, wounding, or other environmental factors weaken the hosts (37). At present, crown gall is the predominant disease encountered on rose cultures in the Mediterranean region, reducing both the vigor of the plants and the yields of marketable flowers (33). The severity of the disease on rose plants can be related to the development and use of new production methods in nurseries, such as vegetative multiplication of plant material. The wounds induced by cutting, grafting, and root pruning generate additional infection sites for Agrobacterium (27). In nurseries, transmission of the bacteria occurs via soil or via water (24). Furthermore, growth conditions encountered in nurseries (temperature and humidity) favor the development of the pathogen. Additionally, the increase in commercial exchanges of contaminated plant material must be taken into account when one is investigating the epidemic spread of the disease. Due to the stability of genetic colonization by Agrobacterium (2), current curative methods are not effective for controlling the disease. In the absence of rose varieties naturally resistant to crown gall disease, further propagation of the disease can be avoided only through prevention and selection of healthy plants before vegetative multiplication. Therefore, methods that allow detection of the pathogen in contaminated plant material must be developed. Better knowledge of the Agrobacterium strains that invade rose plants and the way in which they spread is therefore needed.

Here, we present the establishment of a collection of Agrobacterium isolates that were obtained from diseased rose plants from France, Spain, and Morocco. The physiological and molecular characteristics of these isolates were analyzed, with particular emphasis on the characteristics affecting virulence and tumorigenesis. We collected information about the origins of plant material that was used for flower production and the horticulture conditions used for generating the rose plants. We present data indicating a correlation between the molecular characteristics of Agrobacterium and rose plant origins and discuss the possible implications of our results for a better understanding of the epidemiology of crown gall disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant samples.

The majority of rose plant samples harboring crown gall tumors were graftings obtained from flower producers. Two samples were rootstocks. The 28 samples were collected from 23 different growers in France, Spain, and Morocco between 1991 and 1997. For confidentiality, floriculturists were designated by numbers, and professional grafters, multipliers, and breeders of rootstocks were designated by letters.

Agrobacterium reference strains.

Strains with the prefix CFBP and Agrobacterium sp. strain C58 were obtained from the Collection Française de Bactéries Phytopathogènes (CFBP; Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique [INRA], Angers, France). Strains A6, Bo542, and EU6 were gifts from W. S. Chilton (North Carolina State University, Raleigh). Strains ACH5 and T37 were obtained from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), Villeurbanne, France. Strains 287-7 and 282-1 were obtained from M. M. Lopez (Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias, Moncada, Spain). Strain ANT4 was isolated at INRA, Antibes, France.

Isolation of A. tumefaciens from crown galls.

Tumors were cut from rose plants, washed with water, ground in a mortar, and extracted in sterile water. The insoluble residues were allowed to settle, and 1-μl aliquots of the supernatants were spread on petri dishes containing YPGA medium (5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of Bacto Peptone, 10 g of glucose, and 15 g of agar liter−1) and incubated for 4 days at 25°C. Typical Agrobacterium colonies (16) were picked and dispersed in 1 ml of water at 25°C under continuous agitation. Aliquots from overnight cultures were streaked on YPGA medium. The procedure was repeated until homogeneous bacterial cultures were obtained.

Isolate reference numbers.

The isolates RiM9, RiM10, RiM12, RiM15, RiM19, RiM20, RC21, RiM23, RiM26, RiM27, RiM30, RiM42, RiM45, RiM50, RiM57, RiM60, RiM66, RiM67, RM71, RiM74, and RiM76 were deposited at CFBP and appear in the catalog of phytopathogenic bacterial strains under the numbers CFBP4418, CFBP4419, CFBP4421, CFBP4423, CFBP4424, CFBP4425, CFBP4426, CFBP4427, CFBP4430, CFBP4431, CFBP4434, CFBP4440, CFBP4442, CFBP4443, CFBP4444, CFBP4445, CFBP4447, CFBP4449, CFBP4451, CFBP4453, and CFBP4454, respectively.

Biochemical analysis of the isolates.

The recovered bacteria were assayed for the presence of β-glucosidase, β-galactosidase, and urease activities; the Gram strain response was also investigated (20). Isolates that were identified as belonging to the genus Agrobacterium were stored at room temperature on YPGA medium, as well as under liquid nitrogen in an aqueous solution containing 15% glycerol and 15% dimethyl sulfoxide. The biovars of the isolates were determined according to their growth characteristics on selective medium (3), on 2% NaCl, and on ferric ammonium citrate; production of 3-ketolactose; utilization of citrate; and medium alkalization in the presence of malonic acid, l-tartaric acid, and mucic acid (25). The pathogenicity of the bacteria was assessed by evaluating their ability to induce crown gall formation 3 weeks after the inoculation of rose cuttings. All growth assays and the investigation of tumor induction ability were performed at 25°C.

Opine analyses.

To obtain large tumors and to avoid the extraction of rose compounds interfering with opine analyses, opine production by tumors on galls developing 4 weeks after stem inoculation of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi-nc) with bacteria was analyzed. Opines were extracted from 1 g (fresh weight) of tumors by homogenization of the galls in 10 ml of methanol. The extracts were clarified by filtration through Whatman GF/C filters, dried under vacuum, resuspended in 10 ml of ethyl acetate, and extracted with 10 ml of water. The aqueous phase was reextracted with 10 ml of ethyl acetate and concentrated to 1 ml. For separation of opines, 20 μl of the extracts was spotted on Whatman 3MM paper (38 by 20 cm). Paper electrophoresis was performed at a constant voltage (34 V cm−1) for 1 h in 1 M formic acid–0.8 M acetic acid at pH 1.8 for separating agropine, nopaline, mannopine, chrysopine, and octopine and in 0.15 M formate buffer at pH 2.8 for separating succinamopine and leucinopine (8, 13). Opine spots were revealed as described by Dessaux et al. (13). Authentic nopaline, octopine, and mannopine standards were purchased from Sigma. Leucinopine and succinampine were gifts from W. S. Chilton and P. Guyon (CNRS, Gif sur Yvette, France), respectively. Agropine was synthesized as described previously (12).

Isolation of DNA and PCR protocols.

DNA was extracted as described by Chen and Kuo (6) from 1.5 ml of A. tumefaciens cultures grown for 2 days at 25°C in YPG medium (YPGA medium without agar). All PCR experiments were performed with 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 1× PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 0.1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mg of bovine serum albumin ml−1), 200 μM each nucleotide (Promega), 0.1 μM each primer, 0.25 U of Taq polymerase (Appligène-Oncor, Illkitvh, France), and 25 ng of template DNA. The temperature profile for the amplification of tmr(171), vir(246), and vir(418) was as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 5 s, annealing at 57°C for 15 s, and elongation at 71°C for 30 s, and final extension at 71°C for 3 min. For the amplification of the 16S fragment, the annealing temperature was increased to 59°C. For the amplification of tms(587) and vir(1673), the duration of all steps was doubled. The primers used to amplify Ti plasmid fragments were as follows: FGPtmr530 and FGPtmr701′ for amplifying tmr(171), FGPtms2194′ and FGPtms146′ for amplifying tms(587), FGPvirA2275 and FGPvirB2164′ for amplifying vir(1673), FGPvirB11+21 and FGPvirG15′ for amplifying vir(246), and ANTvirB11887 (5′GGTGAGACAATAGGCGATCT3′) and FGPvirG15′ for amplifying vir(418). Chromosomal DNA corresponding to the 16S rRNA sequence was amplified with primers FGPS6 and FGPS1509′. All primers designated FGP were described previously (28). PCR products were analyzed on 1.2% agarose gels by coelectrophoresis with a 123-bp ladder (Gibco BRL). Electrophoresis and staining of gels with ethidium bromide were carried out by standard procedures (35).

PCR-RFLP.

In a total volume of 15 μl, 5 μl of a PCR product was digested with 8 U of the enzyme CfoI (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), DdeI or MspI (Appligène-Oncor), HaeIII (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom), or MseI (New England Biolabs) in 1× reaction buffer as indicated by the suppliers. Restriction fragments obtained after 1 h of digestion were separated on 8% acrylamide gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Similarity assignments were made by the Dollop software program included in the PHYLIP package (15). Characteristics considered were opine synthesis (succinamopine, nopaline, octopine, agropine, chrysopine, and null); amplification of vir(247), vir(416), and vir(1672); and the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) banding pattern after digestion of vir(416), vir(1672), and tms(587).

RESULTS

Combined physiological and molecular analyses of Agrobacterium.

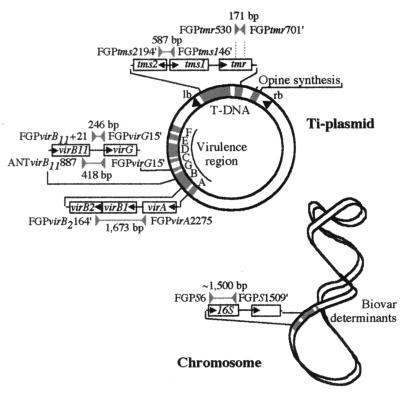

The analysis that was established to identify and distinguish A. tumefaciens isolates involved characteristics determined by chromosomal genes and by genes of the Ti plasmid, as indicated in Fig. 1. For simplicity reasons, species of Agrobacterium were designated according to phytopathogenic characteristics (9). In other words, tumor- and root-inducing agrobacteria were termed A. tumefaciens and A. rhizogenes, respectively. Physiological and molecular characteristics that were determined by the chromosome were biovars (25) and the RFLP of a PCR fragment of the 16S rRNA gene, respectively. Ti plasmid-determined characteristics were opine synthesis in tumors, amplification by specific primers (28) of regions within the tumorigenesis genes tmr and tms and within some virulence genes (Fig. 1), and RFLPs of the tms fragment and the two longest vir gene fragments. The analyses were applied to 17 reference strains of A. tumefaciens from different geographic origins and isolated from different hosts. Four reference strains of A. vitis and two strains of A. rhizogenes were also included (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Schematic and simplified maps of the Ti plasmid and the chromosome from A. tumefaciens. Regions that were used for PCR amplification and physiological characterization of isolates are indicated. For primer assignments, see Materials and Methods. lb and rb, left and right T-DNA borders, respectively.

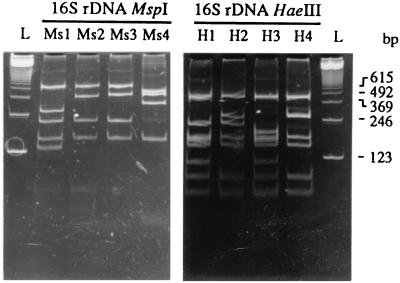

16S rDNA RFLP analysis of reference strains.

A 1,479-bp fragment of the 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) was amplified from all Agrobacterium reference strains with the universal primers FGPS6 and FGPS1509′. The PCR products were digested with the enzymes MspI and HaeIII. A. tumefaciens gave rise to the profiles Ms1 (four restriction sites), Ms2 (three sites), and Ms3 (three sites), and the profiles H1 (seven sites), H2 (six sites), and H3 (seven sites), respectively (Fig. 2). On the basis of the PCR-RFLP profiles, the reference strains were classified into seven chromosome groups belonging to biovars 1 and 2 (Table 1). The two A. rhizogenes strains were from biovar 2. A. rhizogenes A4 showed 16S rDNA RFLP patterns identical to those of A. tumefaciens CFBP1317 and CFBP1935, whereas A. rhizogenes CFBP3001 and A. tumefaciens CFBP296 and CFBP1904 exhibited similar RFLP patterns. All A. vitis strains were from biovar 3. Their 16S rDNA RFLP profiles were not found within the analyzed A. tumefaciens strains.

FIG. 2.

Restriction patterns of the amplified 1,500-bp 16S rDNA fragments after digestion with MspI (profiles Ms1 to Ms4) and HaeIII (profiles H1 to H4). A 123-bp ladder (lanes L) was used as a DNA size marker.

TABLE 1.

Sources, origins, and characteristics of A. tumefaciens reference strains used in this studya

| Strain | Host | Geographic origin | Chromosome

|

Ti plasmid

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biovar | PCR-RFLP of DNA for 16S rRNA (1,500 bp)

|

Opineb | PCR fragmentc

|

PCR-RFLP of:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

vir(418)

|

vir(1673) CfoI

|

tms(587)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MspI RPd

|

HaeIII RPd

|

vir(246) | vir(418) | vir(1673) |

MspI RPd

|

MseI RPd

|

CfoI RPd

|

DdeI RPd

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Ms1 | Ms2 | Ms3 | H1 | H2 | H3 | M1 | M2 | S1 | S2 | C1 | C2 | Ct1 | Ct2 | Ct3 | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | ||||||||

| CFBP296 | Tomato | France | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP1904 | Grapevine | Greece | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| C58 | Sour cherry | United States | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP1932 | Peach | France | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP2516 | Gray poplar | France | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP2177 | Aspen | France | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| T37 | Walnut | Unknown | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP1317 | Bramble | France | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP1935 | Rose | Tahiti | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| 282-1 | Rose | Canary Islands | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| 287-7 | Rose | Spain | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| ACH5 | Prune | United States | 1 | + | + | Oct. | NA | 370e | 2,400f | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | ||||||||||

| A6 | Unknown | Unknown | 1 | + | + | Oct. | NA | 370 | 2,400 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | ||||||||||

| BO542 | Dahlia | Germany | 1 | + | + | Agro. | NA | 370 | 2,400 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | ||||||||||

| ANT4 | Chrysanthemum | France | 1 | + | + | Chrys. | NA | 370 | 2,400 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | + | ||||||||||

| EU6 | Unknown | United States | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| CFBP2746 | Peach | Morocco | 2 | + | + | Null | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

+, positive result; NA, no amplification; ND, not determined.

Opines were nopaline (Nop.), octopine (Oct.), agropine (Agro.), chrysopine (Chrys.), and succinamopine (Succ.). The null type did not induce the production of these opines, leucinopine, or mannopine.

tmr(171) and tms(587) were amplified from all A. tumefaciens reference strains with the primer pairs FGPtmr701′-FGPtmr530 and FGPtms2194′-FGPtms146′ (28), respectively.

RP, restriction profile.

PCR with primer pairs ANTvirB11 887 and FGPvirG15′ led to the amplification of a 370-bp fragment from strains ACH5, A6 BO542, and ANT4.

PCR with primer pairs FGPvirB2164′ and FGPvirA2275 led to the amplification of a 2,400-bp fragment from strains ACH5, A6, BO542, and ANT4.

Opine analyses and PCR of plasmid-encoded pathogenicity genes of reference strains.

Of 17 A. tumefaciens reference strains, 11 caused the synthesis of the opine nopaline in tumors. Five other reference strains caused octopine, agropine, chrysopine, or succinamopine synthesis in tumors. Strain CFBP2746 did not produce these opines, leucinopine, or mannopine. The A. vitis strains caused the production of nopaline, vitopine, cucumopine, and octopine (31). The two strains of A. rhizogenes caused the production of mikimopine (40) and agropine (39).

tmr(171) and tms(587) were amplified from all A. tumefaciens reference strains with the specific primer pairs FGPtmr701′–FGPtmr530 and FGPtms2194′–FGPtms146′ (28), respectively. Independent of the opine type, tmr(171) was also amplified from the A. vitis strains. tms(587) was obtained only from the nopaline-type strains of A. vitis. Neither the tmr nor the tms fragment was amplified from the A. rhizogenes strains. With primer pair FGPvirB11+21–FGPvirG15′, a 247-bp fragment spanning the intergenic region between virB11 and virG from 198 bp 5′ to 49 bp 3′ of the virG start codon was obtained from all nopaline-type strains of A. tumefaciens as well as from the succinamopine-type strain EU6 and strain CFBP2746. No amplification occurred with DNA from strains harboring octopine-, agropine-, and chrysopine-type Ti plasmids (Table 1). The combination of primers ANTvirB11887 and FGPvirG15′ allowed amplification of vir(416) from all nopaline-type strains, the succinamopine-type strain, and strain CFBP2746. This fragment spanned the region from 149 bp 5′ of the stop codon of virB11 to 49 bp 3′ of the start codon of virG. The size of this fragment was reduced to 370 bp when PCR was performed with template DNA isolated from the octopine-, agropine-, and chrysopine-type strains (Table 1). With primer pair FGPvirB2164′–FGPvirA2275, vir(1673), spanning the region from 217 bp 5′ of the stop codon of virA to 164 bp 3′ of the start codon of virB2, was amplified from DNA preparations of nopaline- and succinamopine-type A. tumefaciens strains as well as from strain CFBP2746. The fragment size reached 2,400 bp when PCR was performed with DNA isolated from the octopine-, agropine-, and chrysopine-type strains (Table 1). None of the primer combinations mentioned above allowed amplification of vir fragments from A. vitis or A. rhizogenes DNA.

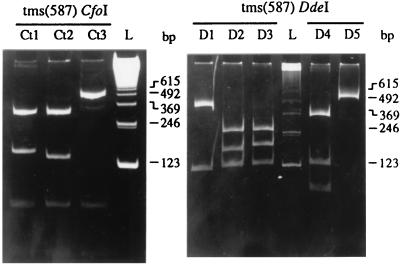

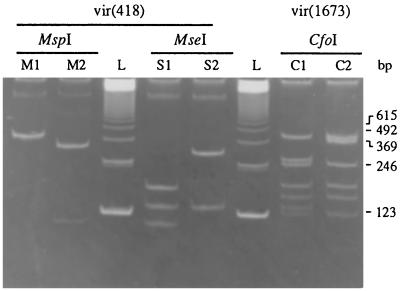

RFLP analysis of amplified tms and vir genes of reference strains.

Digestion of the PCR product tms(587) from A. tumefaciens with the enzymes CfoI and DdeI gave rise to the profiles Ct1 (three restriction sites), Ct2 (three sites), and Ct3 (two sites), and the profiles D1 (one site), D2 (two sites), D3 (two sites), D4 (two sites), and D5 (no site), respectively (Fig. 3). Digestion of vir(418) with the enzymes MspI and MseI led to the profiles M1 (no site) and M2 (one site) and the profiles S1 (two sites) and S2 (one site), respectively (Fig. 4). The PCR product vir(1673) was digested with CfoI and gave rise to the profiles C1 (eight sites) and C2 (seven sites) (Fig. 4). Due to the size differences of the PCR fragments, polymorphisms within the vir region of the octopine-, agropine-, and chrysopine-type strains were not determined. On the basis of the opine type of the Ti plasmids and the RFLP profiles of the PCR products, the Ti plasmids of the 17 A. tumefaciens reference strains fell into 12 plasmid groups. All results of RFLP analyses of PCR products are summarized in Table 1.

FIG. 3.

Restriction profiles after digestion of amplified tms(587) with the enzymes CfoI (profiles Ct1 to Ct3) and DdeI (profiles D1 to D5). A 123-bp ladder (lanes L) was used as a DNA size marker.

FIG. 4.

RFLP analysis of amplified vir(418) and vir(1673). vir(418) was restriction digested with the enzymes MspI (profiles M1 and M2) and MseI (profiles S1 and S2). Digestion of vir(1673) was performed with the enzyme CfoI (profiles C1 and C2). A 123-bp ladder (lanes L) was used as a DNA size marker.

Assembling a collection of A. tumefaciens crown gall isolates from rose plants.

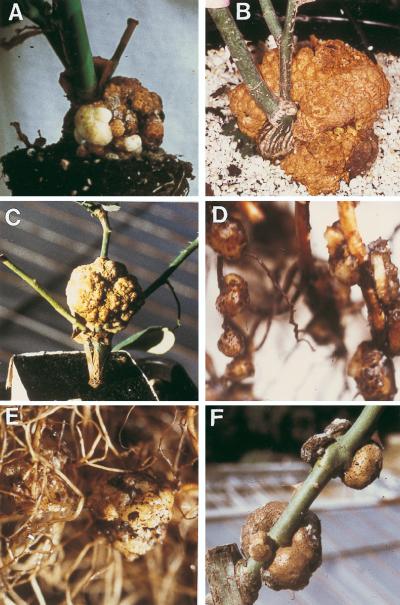

Rose samples that presented symptoms of crown gall disease were collected from 23 different flower producers, rootstock multipliers, or breeders in France, Spain, and Morocco. With the exception of one Rosa canina and three Rosa manetti rootstocks, all others were of the species Rosa indica Major. Twenty-four samples were obtained from flowering, grafted plants. Two samples were obtained from ungrafted rootstocks, and two samples were obtained from grafted rootstocks to be sold to flower producers. Among the 28 different plant samples, 22 had massive crown gall tumors only on the rootstocks (Fig. 5A to C). Two plants had crown gall tumors only on the roots (Fig. 5D to E), and two plants had tumors on both the rootstocks and the roots but not on scions. Galls from roots and rootstocks of the same plant were treated separately. Two samples had the rarely observed galls on scions (Fig. 5F). Altogether, bacteria were obtained from 30 independent galls. We obtained pure cultures of these 30 isolates, which all belonged to the genus Agrobacterium. All isolates were pathogenic and induced the formation of galls when inoculated on rose and tobacco plants.

FIG. 5.

Symptoms of crown gall disease on rose plants. Galls developed frequently on rootstocks (A, B, and C) and roots (D and E) but rarely on scions (F).

16S rDNA RFLP analysis of rose isolates.

The 1,479-bp fragment of the 16S rDNA was amplified from all rose isolates. Digestion of the PCR products from 27 isolates with MspI gave rise to profile Ms1 or Ms2. No profile corresponding to Ms3 was observed. MspI digestion of PCR products from three rose isolates yielded a new profile, Ms4 (three restriction sites; Fig. 2). Digestion of the 16S rDNA fragment with HaeIII gave rise to the profiles H1, H2, and H3 for PCR products from 26 isolates. A new profile, H4 (six sites), was obtained after HaeIII digestion of the PCR products from four isolates. Three isolates gave rise to the novel profile Ms4-H4, and one isolate had the novel profile Ms2-H4. However, 21 of the isolates had the most represented profiles Ms1-H1 and Ms2-H2 (Table 2), as already observed with Agrobacterium reference strains. On the basis of the PCR-RFLP profiles, the rose isolates were classified into seven chromosome groups belonging to biovars 1 and 2. No isolate was classified as biovar 3.

TABLE 2.

Origins of rose samples and characteristics of the A. tumefaciens isolates obtained from crown galls on these plantsa

| Rose sampleb | Date obtained (mo/yr) | Geographic originc | Crown gall locationd | Chromosome

|

Ti-plasmid

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biovar | PCR-RFLP of DNA for 16S rRNA (1,500 bp)

|

Opinee | PCRf

|

PCR-RFLP of:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

vir(418)

|

vir(1673), CfoI

|

tms(587)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

MspI RPd

|

HaeIII RPd

|

vir(246) | vir(418) | vir(1673) |

MspI RPg

|

MseI RPg

|

CfoI RPg

|

DdeI RPg

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Ms1 | Ms2 | Ms4 | H1 | H2 | H3 | H4 | M1 | M2 | S1 | S2 | C1 | C2 | Ct1 | Ct2 | D1 | D2 | |||||||||

| RiM9 | 01/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM10 | 02/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM10r | 02/91 | France (SE) | Roots | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM89 | 02/91 | Morocco (N) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM12 | 03/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM15 | 04/91 | Spain (S) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM18.1 | 06/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM18.2 | 06/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM18.2r | 06/91 | France (SE) | Roots | 2 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM19 | 07/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM20 | 07/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RC21 | 07/91 | France (NE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM23 | 10/91 | France (W) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM26 | 11/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM27 | 11/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM30 | 11/91 | France (SE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM42 | 04/92 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM45 | 06/92 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM50 | 06/92 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM57 | 01/93 | France (SE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM60 | 04/93 | France (NE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM66r | 02/94 | France (SE) | Roots | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM67r | 04/94 | France (SE) | Roots | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM74 | 11/94 | France (SE) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM76 | 11/94 | France (SE) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM71 | 02/95 | Spain (S) | Rst. | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RM77 | 07/95 | Spain (S) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Succ. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RM78 | 07/95 | Spain (S) | Rst. | 2 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM96s | 11/96 | France (SE) | Scions | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| RiM97s | 11/96 | France (SE) | Scions | 1 | + | + | Nop. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

+, positive result.

Rose samples were grafted or ungrafted rootstocks of the species R. indica Major (RiM), R. canina (RC), or R. manetti (RM). Designations for A. tumefaciens isolates were based on rose sample designations. Galls originated from rootstocks (no suffix), roots (“r” suffix), or scions (“s” suffix).

Geographic origins were as follows: France (SE), Var and Alpes-Maritimes, southeast France; France (W), Loire-Atlantique, western France; France (NE), Moselle, eastern France; Spain (S), Alicante, southern Spain; Morocco (N), Fes, northern Morocco.

Rst., rootstocks.

Opines were succinamopine (Succ.) and nopaline (Nop.).

tmr(171) and tms(587) were amplified from all rose isolates with the primer pairs FGPtmr701′-FGPtmr530 and FGPtms2194′-FGPtms146′ (28), respectively.

RP, restriction profile.

Ti plasmid characteristics of rose isolates.

Among the A. tumefaciens rose isolates, 16 caused the synthesis of succinamopine in tumors. All other rose isolates induced the production of nopaline in crown gall tumors (Table 2), and no other opine synthesis trait was found. tmr(171) and tms(587) as well as vir(247), vir(416), and vir(1673) were amplified by PCR from all rose isolates (Table 2).

Restriction digestion of the rose isolate PCR product tms(587) with CfoI and DdeI gave rise to the simple profile Ct1 and Ct2 and the profile D1 and D2, respectively (Fig. 3). Digestion of vir(418) with MspI and MseI led to the profile M1 and M2 and the profile S1 and S2, respectively, as was observed for A. tumefaciens reference strains. Similarly, restriction digestion of vir(1673) with CfoI engendered the profiles C1 and C2 (Fig. 4 and Table 2). On the basis of the opine type of the Ti plasmids and the RFLP profiles of the PCR products, the Ti plasmids of the 30 rose isolates of A. tumefaciens fell into seven plasmid groups (Table 3). Groups II, V, VI, and VII had new characteristics that were not encountered during the analysis of the reference strains. The predominant groups II and III represented 22 of the 30 isolates. With the exception of one isolate (RiM45) that defined a specific plasmid group, all succinamopine-type isolates were from plasmid group II. However, the 15 isolates of this group could be dispatched over five of the seven chromosome groups. Among the nopaline-type isolates, seven belonged to plasmid group III. Although showing the same Ti plasmid characteristics, they were from three different chromosome groups. Thus, among the rose isolates of A. tumefaciens, no specific correlation between plasmid type and chromosome characteristics was found.

TABLE 3.

Classification of the analyzed A. tumefaciens isolates into Ti plasmid groupsa

| Profile tms(587) |

vir(1673) profile C1

|

vir(1673) profile C2

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile vir(418)M1S1

|

Profile vir(418)M2S1

|

Profile vir(418)M1S1

|

Profile vir(418)M1S2

|

Profile vir(418)M2S2

|

|||||||||||

| Opine | Isolates | Group | Opine | Isolates | Group | Opine | Isolates | Group | Opine | Isolates | Group | Opine | Isolates | Group | |

| Ct1D2 | Succ. | RiM45 | I | ||||||||||||

| Nop. | CFBP1904 | Nop. | CFBP296 | Nop. | RiM10 | V | |||||||||

| Nop. | C58 | Nop. | RiM10r | V | |||||||||||

| Nop. | CFBP1932 | ||||||||||||||

| Nop. | CFBP2516 | ||||||||||||||

| Ct2D1 | Nop. | 282-1 | Nop. | RiM97s | VII | Nop. | RiM89 | III | |||||||

| Nop. | RiM12 | III | |||||||||||||

| Nop. | RiM15 | III | |||||||||||||

| Nop. | RiM30 | III | |||||||||||||

| Nop. | RiM57 | III | |||||||||||||

| Nop. | RiM60 | III | |||||||||||||

| Nop. | RiM66r | III | |||||||||||||

| Nop. | 282-7 | III | |||||||||||||

| Ct2D2 | Nop. | RiM67r | IV | Succ. | RiM9 | II | Nop. | RiM96s | VI | ||||||

| Nop. | RM71 | IV | Succ. | RiM18.1 | II | ||||||||||

| Nop. | RM78 | IV | Succ. | RiM18.2 | II | ||||||||||

| Nop. | CFBP2177 | IV | Succ. | RiM18.2r | II | ||||||||||

| Nop. | T37 | IV | Succ. | RiM19 | II | ||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM20 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RC21 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM23 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM26 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM27 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM42 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM50 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM74 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RiM76 | II | |||||||||||||

| Succ. | RM77 | II | |||||||||||||

Opines were succinamopine (Succ.) and nopaline (Nop.). Rose isolates are shown in plain text, and reference strains are shown in italic type.

Relationship between A. tumefaciens genotypes and the origins of rose plant samples.

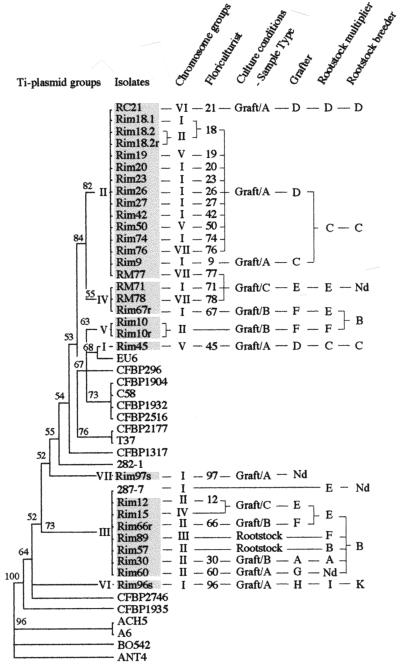

To draw conclusions regarding the propagation of A. tumefaciens in rose cultures, we collected information on the origins of rootstocks, the conditions for rootstock propagation, and the culture conditions used for flower production. This information was compared with the experimental data that we obtained by molecular characterization of the bacterial isolates. We did not find any apparent correlation between the chromosome characteristics of the A. tumefaciens isolates and the origin of the rose plants or the culture conditions. In contrast, a strong correlation between the plasmid characteristics of the bacterial isolates and the origin of rootstock clones was evident (Fig. 6). A similarity analysis with equal weights of Ti plasmid characteristics confirmed the homogeneity among the isolates that clustered in defined plasmid groups (Fig. 6). With the exception of RM77, all succinamopine-type isolates were from rose plants that were multiplied and cultured under conditions that we termed graft/A (Fig. 6). A further common feature identified was that all rootstocks which gave rise to rose plants contaminated by succinamopine-type isolates were processed by breeder C or D (with the exception of RM77). Additionally, breeder D frequently obtained plant material from breeder C (Fig. 6). RM77 was the only isolate originating from a plant that was cultivated by the graft/C method and harboring a group II plasmid. This isolate had the same chromosomal background as the nopaline-type isolate RM78, which was from a plant produced by multiplier-grafter E. The group II Ti plasmid of RM77 might have originated in rootstocks obtained from breeder C or D, but in this case it was impossible to trace the contamination back to its origin (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Similarity analysis of discrete Ti plasmid characteristics of A. tumefaciens reference strains and rose isolates, classification of chromosome groups of rose isolates, and origin and culture conditions of the plants that served for bacterial isolation. Characteristics analyzed were opine type, amplification of vir gene fragments, and PCR-RFLP banding patterns for the long vir and tms fragments. Values indicating the confidence of branch point assignments were created in a bootstrap analysis from 1,000 trials. Rose isolates of A. tumefaciens are shown in shaded boxes. Sample types were either rootstocks or grafted plants. In graft/A, grafting and planting into pots occurred at the same time. Plants were grown under defined culture conditions and were sold for flower production 6 to 8 weeks later. In graft/B, cuttings of the rootstock were planted into pots and cultured under defined conditions. Graftings were performed after root formation, and plants were sold for flower production 10 to 12 weeks after cutting. In graft/C, cuttings of the rootstocks were planted in the ground, and graftings were performed 6 month later. Plants were sold for flower production after 1 year. Nd, neither the breeder of R. manetti rootstocks for samples RM77, RM71, and RM78 nor the breeder of the rootstock for sample RiM97 could be determined. Grafter F propagated rootstocks in Morocco but performed graftings in France on either his own rootstocks (RiM10 and RiM89) or rootstocks that were obtained from grafter/multiplier E (RiM66 and RiM67).

All isolates that clustered in the well-represented plasmid group III were isolated from rose plants grafted on rootstocks obtained from breeder B. Isolate RiM57 (chromosome group II) was recovered from a rootstock obtained directly from this breeder. Additionally, the culture conditions that gave rise to the different gall-diseased samples were heterogeneous (graft/A, graft/B, and graft/C), making contamination through soil or water improbable. The only A. tumefaciens reference strain harboring a group III Ti plasmid (strain 287-7) was isolated in Spain from a rose plant propagated by multiplier/grafter E. In general, multiplier/grafter E acquired rootstocks from breeder B.

Two A. tumefaciens isolates in our collection were from rose plant scions, on which crown galls rarely developed. Both isolates belonged to independent plasmid groups, and no correlation could be established between disease and rootstock origin (Fig. 6). We believe that the contamination happened during the grafting process or was due to wounding occurring between grafting and flower production. In general, the occasional infection of scions did not contribute to the propagation of the disease.

DISCUSSION

We performed an integrated analysis of the physiological and molecular characteristics of 30 A. tumefaciens isolates that were recovered from diseased rose plants. In comparison to the reference bacterial strains used in this study, the rose isolates showed strong homogeneity, whatever the geographic origin of the samples.

This homogeneity was characterized in particular by Ti plasmids encoding only the opines succinamopine and nopaline, although more than 20 different opines are known (14, 40). One surprising finding was that 16 of 30 isolates harbored succinamopine-type Ti plasmids. Plasmids encoding this opine are relatively rare, and until now only three A. tumefaciens strains that induce succinamopine production in galls were described (8). The virulence traits of isolates harboring succinamopine-type Ti plasmids were more stable than those of nopaline-type isolates. As already reported in a previous study (38), nopaline-type isolates lost virulence when kept at temperatures above 30°C. We found that this loss of virulence was correlated with an absence of amplification by PCR of vir, tms, or tmr gene fragments from the DNA of the isolates and was thus most probably due to a loss of the Ti plasmid (data not shown). In contrast, none of the succinamopine-type isolates lost virulence and appeared to be well adapted to an extended exposure to the high temperatures that commonly occur in the countries where the rootstocks were selected and propagated. The opine type of a Ti plasmid also influences the effectiveness of conjugal transfer between bacteria (30 and references therein). Although the effect of succinamopine on this transfer has not yet been analyzed, our results suggest that succinamopine-type Ti plasmids have been transferred frequently to different chromosomal backgrounds and that recipient strains are better adapted for the infection of rose cultures.

Despite the fact that rose isolates constitute a rather homogeneous group, their specific characteristics allowed differentiation from our reference strains. The plasmid characteristics of most of the rose isolates thus defined groups that were not represented among the reference strains. Furthermore, this specificity was also found at the chromosome level. Usually, the analysis of 16S rDNA provides good information for the identification of Agrobacterium species (36, 41) and biovars within A. tumefaciens. Ponsonnet and Nesme (34) amplified a 1,500-bp 16S rDNA fragment from 41 different Agrobacterium strains by using primers FGPS6 and FGPS1509′. They digested the fragments with HaeIII and found that the profiles H1 and H3 always correlated with strains from biovar 1, while biovar 2 strains gave rise to profile H2. In the present study, we found the same strict correlation when analyzing the reference strains. In contrast, 5 of the 30 rose isolates did not fit into the above scheme or gave rise to the new profile H4 upon analysis of their 16S rRNA genes. The 16S rDNA PCR-RFLP profiles that we encountered most frequently for 21 of the 30 isolates from all seven plasmid groups were Ms1-H1 (biovar 1) and Ms2-H2 (biovar 2). It seems likely that bacteria with these chromosomal backgrounds are common in rose cultivation areas and are good recipients for Ti plasmids.

To our knowledge, the present study represents the first demonstration of a close correlation between the Ti plasmid type of A. tumefaciens isolates found in diseased rose plants from different countries and a common origin of the plant samples that were used for isolation of the bacteria. The results indicate that rootstocks from breeder C or D were the source for the dissemination of the succinamopine-type isolates that we found in rose plants from 14 independent flower producers. We believe that the succinamopine-type group II Ti plasmid originated in a rootstock from one of these breeders and that this plasmid was further disseminated to other A. tumefaciens strains through conjugal transfer. Even more clearly, our findings strongly suggest that rootstocks obtained from breeder B were the origin of the dissemination of the group III Ti plasmid to eight independent nurseries in three different Mediterranean countries.

To obtain grafted plants, three culture methods were used: graft/A, graft/B, and graft/C. In terms of phytopathology, the procedures involving graft/A and graft/B almost eliminate the risk of new contamination of plants by soil bacteria, as all steps are performed with a soil-free substrate. However, the rapid turnovers and exchanges between rootstocks and scions favor the propagation of disease through contaminated material. In contrast, the classical graft/C method restricts this risk but favors new contamination by soil bacteria. For our collection, only the three samples isolated from R. manetti rootstocks and samples RiM12 and RiM15 were cultivated by the graft/C method by multiplier/grafter E. The five A. tumefaciens isolates from these samples could be classified into four distinct chromosome groups. In contrast, the 14 isolates from graft/A samples, which were all obtained from breeder C, were from 5 chromosome groups. Thus, plants in soil cultures acquire bacteria with different chromosomal backgrounds more frequently than do those in cultures with soil-free substrates.

In grapevine, A. tumefaciens can persist in the roots but in the spring becomes mobilized throughout the plant with the vessel sap (5, 18, 19). In tobacco, persisting Agrobacterium can be detected preferentially in the basal parts of the plants (21). These authors stressed the risks of dissemination through vegetative propagation, which involves stem bases and roots. We developed an A. tumefaciens detection method based on PCR of vir(418). With this method, we were able to detect the bacteria in rose plants even in the absence of disease symptoms. Furthermore, in diseased plants the bacteria could be localized in organs distant from crown galls (data not shown). Movement of Agrobacterium within the plants would account for the identification of the same isolates in cuttings and roots (RiM10 and RiM10r; RiM18.2 and RiM18.2r [Table 2]). Our results indicate that Agrobacterium can persist in rose plants and that it is able to move systemically in the plants. These factors increase the risks for dissemination of the microorganism through vegetative propagation of rose plants.

In summary, we have shown that the exponential spread of crown gall disease in Mediterranean rose cultures is due to the vegetative propagation of rootstocks; to the frequent exchange of plant material between professional breeders, multipliers, and grafters; and to the increasing turnover rates for flower production. As efficient chemical or genetic control of the disease will not be applicable in the near future and as it will not be possible to restrict commercial exchanges and to decrease turnover rates, further propagation of the disease can be reduced only through selection of healthy rootstocks. Thus, sensitive methods for the detection and characterization of the bacteria are required. In this study, we presented putative targets for detection by PCR (vir, tms, and tmr regions) and a subset of molecular markers that will be valuable tools for such purposes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all growers who kindly provided us with samples of crown gall-diseased rose plants. We are grateful to William Scott Chilton for the gifts of opines and of A. tumefaciens A6, Bo542, and EU6 and to Maria Lopez for strains 287-7 and 282-1. We thank Claude Antonini, Louis Simonini, and Jean-Marie Drapier for plant care. We thank Neil Ledger for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by grant 639/92 from the Association Nationale de la Recherche Technique and Comité National Interprofessionnel de l’Horticulture to S.P. and by EEC contract ERBIC18CT970198 to X.N. and Y.D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck von Bodman S, Hayman G T, Farrand S K. Opine catabolism and conjugal transfer of the nopaline Ti plasmid pTiC58 are coordinately regulated by a single repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:643–647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beijersbergen A, Hooykaas P J J. The virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. In: Nester E W, Verma D P S, editors. Advances in molecular genetics of plant-microbe interactions. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brisbane P G, Kerr A. Selective media for three biovars of Agrobacterium. J Appl Bacteriol. 1983;54:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bundock P, Hooykaas P. Interactions between Agrobacterium tumefaciens and plant cells. In: Romeo J T, Downum K R, Verpoorte R, editors. Phytochemical signals and plant-microbe interactions. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burr T J, Katz B H. Isolation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens biovar 3 from grapevine galls and sap, and from vineyard soil. Phytopathology. 1983;73:163–165. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W P, Kuo T T. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of gram-negative bacterial genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2260. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.9.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chilton M D, Drummond M H, Merio D J, Sciaky D, Montoya A L, Gordon M P, Nester E W. Stable incorporation of plasmid DNA into higher plant cells: the molecular basis of crown gall tumorigenesis. Cell. 1977;11:263–271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilton W S, Tempé J, Matzke M, Chilton M D. Succinamopine: a new crown gall opine. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:357–362. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.357-362.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conn H J. Validity of the genus Alcaligenes. J Bacteriol. 1942;44:353–360. doi: 10.1128/jb.44.3.353-360.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das A. DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to plant cells in crown gall tumor disease. Subcell Biochem. 1998;29:343–363. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1707-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Cleene M, De Ley J. The host range of crown gall. Bot Rev. 1976;42:389–466. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dessaux Y, Guyon P, Farrand S K, Petit A, Tempé J. Agrobacterium Ti and Ri plasmids specify enzymatic lactonization of mannopine to agropine. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:2549–2559. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-9-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dessaux Y, Petit A, Tempé J. Opines in Agrobacterium biology. In: Verma D P S, editor. Molecular signals in plant-microbe communications. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1992. pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dessaux Y, Petit A, Tempé J. Chemistry and biochemistry of opines, chemical mediators of parasitism. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogenetic inference package (version 3.572). Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kersters K, De Ley J. Agrobacterium Conn 1942. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 244–254. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H, Farrand S K. Opine catabolic loci from Agrobacterium plasmids confer chemotaxis to their cognate substrates. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1998;11:131–143. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehoczky J. Spread of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in the vessels of the grapevine after natural infection. Phytopathol Z. 1968;63:239–246. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehoczky J. Further evidences concerning the systematic spread of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in the vascular system of grapevine after natural infection. Vitis. 1971;10:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippincott J A, Lippincott B B, Starr M P. The genus Agrobacterium. In: Stolp H, Starr M P, Trüper H G, Balows A, Schlegel H G, editors. The prokaryotes: a handbook on habitats, isolation and identification of bacteria. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1981. pp. 842–855. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matzk A, Mantell S, Schiemann J. Localization of persisting agrobacteria in transgenic tobacco plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1996;9:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melchers L S, Hooykaas P J J. Virulence of Agrobacterium. Oxford Surv Plant Mol Cell Biol. 1987;4:167–220. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer A D, Aebi R, Meins F., Jr Tobacco plants carrying a tms locus of Ti-plasmid origin and the H1-1 allele are tumor prone. Differentiation. 1997;61:213–221. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1997.6140213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore L W, Cooksey D A. Biology of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: plant interactions. Int Rev Cytol. 1981;13(Suppl.):15–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore L W, Kado C I, Bouzar H. Gram-negative bacteria. A Agrobacterium. In: Schaad N W, editor. Laboratory guide for identification of plant pathogenic bacteria. 2nd ed. St. Paul, Minn: The American Phytopathological Society; 1988. pp. 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris R O. Genes specifying auxin and cytokinin biosynthesis in phytopathogens. Ann Rev Plant Physiol. 1986;37:509–538. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nesme X, Michel M F, Digat B. Population heterogeneity of Agrobacterium tumefaciens in galls of Populus L. from a single nursery. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:655–659. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.655-659.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nesme X, Picard C, Simonet P. Specific DNA sequences for detection of soil bacteria. In: Trevors J T, van Elsas J D, editors. Nucleic acids in the environment. Methods and applications. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1995. pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nester E W, Gordon M P, Amasino R M, Yanofsky M F. Crown gall: a molecular and physiological analysis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1984;35:387–413. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oger P, Kim K-S, Sacket R L, Piper K R, Farrand S K. Octopine-type Ti plasmids code for a mannopine-inducible dominant-negative allele of traR, the quorum-sensing activator that regulates Ti plasmid conjugal transfer. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:277–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulus F, Huss B, Bonnard G, Ride M, Szegedi E, Tempé J, Petit A, Otten L. Molecular systematics of biotype III Ti plasmids of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1989;2:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piper K R, Beck von Bodman S, Farrand S K. Conjugation factor of Agrobacterium tumefaciens regulates Ti plasmid transfer by autoinduction. Nature. 1993;362:448–450. doi: 10.1038/362448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poncet C, Antonini A, Bettachini A, Pionnat S, Simonini L, Dessaux Y, Nesme X. Impact of the crown gall disease on vigor and yield of rosetrees. Acta Hortic. 1996;424:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponsonnet C, Nesme X. Identification of Agrobacterium strains by PCR-RFLP analysis of pTi and chromosomal regions. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:300–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00303584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawada H, Ieki H, Oyaizu H, Matsumoto S. Proposal for rejection of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and revised descriptions for the genus Agrobacterium and for Agrobacterium radiobacter and Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;3:694–702. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-4-694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroth M N, McCain A H, Foott J H, Huisman O C. Reduction in yield and vigor of grapevine caused by crown gall disease. Plant Dis. 1988;72:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tempé J, Petit A, Holsters M, Van Montagu M, Schell J. Thermosensitive step associated with transfer of the Ti plasmid during conjugation: possible relation to transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2848–2849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tepfer D A, Tempé J. Production d’agropine par des racines formées sous l’action d’Agrobacterium rhizogenes, souche A4. C R Acad Sci. 1981;292:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaudequin-Dransart V, Petit A, Poncet C, Ponsonnet C, Nesme X, Jones J B, Bouzar H, Chilton W S, Dessaux Y. Novel Ti plasmids in Agrobacterium strains isolated from fig tree and chrysanthemum tumors and their opinelike molecules. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:311–321. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willems A, Collins M D. Phylogenetic analysis of rhizobia and agrobacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequence. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:305–313. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-2-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winans S C. Two-way chemical signaling in Agrobacterium-plant interactions. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:12–31. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.12-31.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Murphy P J, Kerr A, Tate M E. Agrobacterium conjugation and gene regulation by N-acyl-l-homoserine lactones. Nature. 1993;362:446–448. doi: 10.1038/362446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]