Abstract

Target of rapamycin complex 1 (TORC1) promotes biogenesis and inhibits the degradation of ribosomes in response to nutrient availability. To ensure a basal supply of ribosomes, cells are known to preserve a small pool of dormant ribosomes under nutrient‐limited conditions. However, the regulation of these dormant ribosomes is poorly characterized. Here, we show that upon inhibition of yeast TORC1 by rapamycin or nitrogen starvation, the ribosome preservation factor Stm1 mediates the formation of nontranslating, dormant 80S ribosomes. Furthermore, Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes are protected from proteasomal degradation. Upon nutrient replenishment, TORC1 directly phosphorylates and inhibits Stm1 to reactivate translation. Finally, we find that SERBP1, a mammalian ortholog of Stm1, is likewise required for the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes upon mTORC1 inhibition in mammalian cells. These data suggest that TORC1 regulates ribosomal dormancy in an evolutionarily conserved manner by directly targeting a ribosome preservation factor.

Keywords: dormant ribosomes, proteasome, SERBP1, Stm1, TORC1

Subject Categories: Signal Transduction, Translation & Protein Quality

A conserved regulatory mechanism ensures a basal supply of ribosomes during nutrient starvation in yeast and human cells.

Introduction

The ribosome pool is tightly regulated to ensure appropriate translational capacity. Under nutrient‐rich conditions, cells enhance ribosome biogenesis to promote protein synthesis. By contrast, under nutrient‐limiting conditions, cells reduce ribosome biogenesis and degrade ribosomes via autophagy (ribophagy) or proteasomal degradation (Kraft et al, 2008; Prossliner et al, 2018; An & Harper, 2020; Wang et al, 2020). However, excessive degradation may deplete ribosomes and impede the resumption of cell growth upon restoration of favorable growth conditions (Warner, 1999; Kressler et al, 2010). To avoid excessive degradation during starvation, so‐called preservation factors protect a small pool of nontranslating, vacant ribosomes (Ben‐Shem et al, 2011; Brown et al, 2018; Prossliner et al, 2018; Wells et al, 2020). The regulation of the preservation and subsequent re‐activation of mRNA‐free dormant ribosomes is not yet understood.

TORC1 is an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine kinase that promotes cell growth in response to nutrients and growth factors (Gonzalez & Hall, 2017; Saxton & Sabatini, 2017; Battaglioni et al, 2022). In budding yeast, TORC1 comprises TOR1/TOR2, Kog1, and Lst8 while mammalian TORC1 (mTORC1) consists of mTOR, the Kog1 ortholog RAPTOR, and mLST8 (Hara et al, 2002; Kim et al, 2002; Loewith et al, 2002). Under nutrient‐sufficient conditions, TORC1 up‐regulates ribosome biogenesis by promoting the transcription of rRNAs and expression of ribosomal proteins, and prevents ribosomal degradation by inhibiting ribophagy and the proteasome (Mayer & Grummt, 2006; Kraft et al, 2008; An & Harper, 2020). Inhibition of TORC1 by starvation or rapamycin treatment reduces translation and leads to the accumulation of 80S ribosomes (Barbet et al, 1996; Larsson et al, 2012). The accumulation of 80S ribosomes rather than free 40S and 60S subunits upon TORC1 inhibition is unexplained.

Stm1 is a yeast ribosome preservation factor (Van Dyke et al, 2013). In vacant 80S ribosomes isolated from starved cells, Stm1 is at the interface of the two ribosomal subunits and occupies the mRNA tunnel of the 40S subunit, thereby excluding mRNA (Ben‐Shem et al, 2011). Stm1 was also shown to interact with translating ribosomes (Van Dyke et al, 2006). Furthermore, cells lacking Stm1 are hypersensitive to nitrogen starvation or rapamycin treatment (Van Dyke et al, 2006), suggesting a functional but so far poorly characterized interaction between Stm1 and TORC1.

Here, we show that upon TORC1 inhibition or nitrogen starvation, Stm1 forms vacant 80S ribosomes. Furthermore, Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes are protected from proteasomal degradation. Upon restoration of growth conditions, TORC1 directly phosphorylates and inhibits Stm1, thereby activating dormant ribosomes and stimulating translation re‐initiation. Such regulation of dormant ribosomes is evolutionarily conserved as mTORC1 similarly regulates SERBP1 (SERPINE1 mRNA binding protein) in mammalian cells.

Results

Stm1 occupies 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition

TORC1 inhibition or nutrient depletion leads to the accumulation of nontranslating 80S ribosomes (Kaminskas, 1972; van Venrooij et al, 1972; Barbet et al, 1996; Ashe et al, 2000; Liu & Qian, 2016). Why 80S ribosomes rather than free 40S and 60S subunits accumulate is not understood. To investigate this, we performed mass spectrometry on 80S ribosomes isolated from rapamycin‐treated and ‐untreated cells (Fig 1A). We observed enrichment of factors involved in ribosome preservation, translation initiation, ribosome biogenesis, or mRNA degradation in the 80S fraction from rapamycin‐treated cells compared with‐untreated cells. These factors included Stm1, Dbp2, Mrt4, Asc1, Ski2, Sui3, and Ssb1 (Fig EV1A). Stm1 was particularly prominent among the proteins enriched in the 80S fraction from TORC1‐inhibited cells (Fig 1A and B).

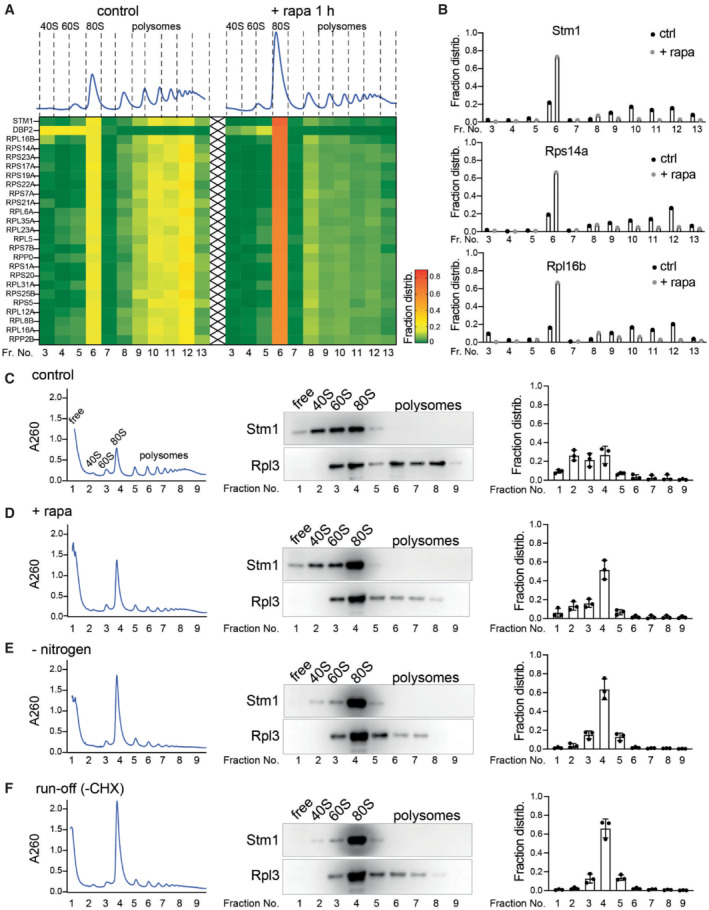

Figure 1. Stm1 binds to vacant 80S ribosome upon TORC1 inhibition.

-

AHeat map showing the fraction distribution of the top 25 most abundant proteins across the polysome profiles treated with or without rapamycin for 1 h. The proteins are sorted according to their distribution in the 80S fraction (fraction 6) upon rapamycin treatment (Fraction number 6). Individual polysome profiles were separated on a 5–50% sucrose density gradient containing 50 mM KCl into 14 fractions, and fraction numbers 3–13 were analyzed by mass spectrometry.

-

BDistribution of proteins Stm1, Rps14a, and Rpl6b in the fractions across the polysome profile obtained with or without rapamycin treatment for 1 h as identified by MS/MS.

-

C–FPolysome profiling of yeast cells with (C–E) or without (F) cycloheximide (CHX) treatment, immunoblots for Stm1 and Rpl3 in polysome fractions, and quantification of Stm1 distribution across the polysome profiles of cells grown under nutrient‐rich condition (C, F), rapamycin treatment for 1 h (D), or nitrogen starvation for 1 h (E). Individual polysome profiles were fractionated on a 5–50% sucrose density gradient containing 150 mM KCl into nine fractions, precipitated, and immunoblotted for Stm1 and Rpl3. Rpl3 is used as a loading control. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Figure EV1. Characterization of the interaction of Stm1 with ribosomes.

- Heat map showing the fraction distribution of most abundant (top 80) ribosome‐associated proteins and their response to rapamycin treatment.

- Immunoblots of Stm1, Rpl3, and Pab1 in fractions obtained from polysome profiles of yeast cells under control conditions, nitrogen starvation for 1 h, or rapamycin treatment for 1 h. The polysome profiles were analyzed with or without RNase I treatment for 10 min using 50 mM KCl containing 5–50% sucrose density gradients. Representative blots from a minimum of three independent experiments are shown.

- Immunoblot of Stm1 and Rpl3 in the polysome profile fractions of cells under control condition or nitrogen starved for 1 h, analyzed using sucrose density gradients containing 50, 150, 300, or 800 mM KCl, or from cell extracts treated with 50 mM EDTA (analyzed in 50 mM KCl sucrose density gradients).

- Immunoblot of Stm1 and Rpl3 in the polysome profile fractions of cells grown under nitrogen starved for 1 h with or without nitrogen restimulation for 30 min and analyzed using sucrose density gradients containing 150 mM KCl.

- Relative fraction distribution of Stm1 in 80S fraction. Minimum of three biological replicates are analyzed by multiple unpaired t‐tests. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

In the crystal structure of 80S ribosomes, Stm1 was found to occupy the mRNA tunnel in otherwise vacant 80S ribosomes, rendering them translationally inactive (Ben‐Shem et al, 2011). However, Van Dyke et al (2006) showed, and we confirmed (Fig EV1B), that Stm1 associates with both 80S and polysomal ribosomes. This raises the question of how Stm1 is associated with translating polysomes. We speculated that Stm1 might associate nonspecifically with polysomes, possibly due to the low KCl concentration (50 mM) in the sucrose density gradients of the above experiments. Nonspecific interactions of proteins with ribosomes are known to be KCl sensitive (Fleischer et al, 2006). Hence, we re‐analyzed the interaction of Stm1 with ribosomes using sucrose density gradients containing higher KCl concentrations (150, 300, and 800 mM). Notably, at 150 mM KCl, the association of Stm1 with polysomes was lost, whereas the interaction with 80S ribosomes was unaffected, suggesting that the interaction of Stm1 with polysomes is nonspecific (Fig EV1C). We note that, at 150 mM KCl, Stm1 was associated with 40S and 60S subunits in addition to 80S (Figs 1C and EV1C). At 300 and 800 mM KCl, Stm1 was found mainly in the ribosome‐free fraction. Furthermore, the inhibition of TORC1 by rapamycin or nitrogen starvation led to an accumulation of Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes (Figs 1D and E, and EV1D and E). To confirm that Stm1 is associated with nontranslating 80S ribosomes, we analyzed polysome profiles in the absence of cycloheximide (−CHX), a condition that allows actively translating ribosomes to run‐off mRNA. Ribosome run‐off increased (~3‐fold) the accumulation of Stm1 in the 80S ribosome fraction compared with the CHX‐treated samples (Figs 1F and EV1E). Furthermore, mRNA‐free ribosomes are sensitive to high salt concentrations (van den Elzen et al, 2014). Indeed, starvation‐induced dormant 80S ribosomes split into 40S and 60S subunits in the presence of 300 and 800 mM KCl (Fig EV1C). Thus, Stm1 is associated with nontranslating, dormant 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition or nutrient deprivation.

Stm1 forms dormant 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition

To understand the role of Stm1 in vacant 80S ribosomes, we analyzed polysome profiles of wild‐type and stm1Δ strains. We observed little difference in the overall polysome profiles of wild‐type and stm1Δ cells grown in nutrient‐rich conditions (Fig 2A), suggesting that Stm1 has no role in normally growing cells. Upon TORC1 inhibition by rapamycin treatment or nitrogen starvation for 1 h, wild‐type cells displayed the expected shift of polysomes to 80S ribosomes (Fig 2B and C). By contrast, stm1Δ cells displayed a shift of polysomes to 40S and 60S subunits, suggesting that Stm1 is required for the formation or stabilization of nontranslating 80S ribosomes (Fig 2B and C). Confirming that Stm1 is required for the stabilization or formation of vacant 80S ribosomes, ribosome run‐off (polysome profiling in the absence of cycloheximide) led to increased accumulation of 40S and 60S subunits and a corresponding decrease in 80S ribosomes in stm1Δ cells grown in nutrient‐rich conditions, compared with wild‐type cells (Fig 2D). To investigate whether Stm1 is required specifically for the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes, we treated nitrogen‐starved cells with the crosslinker formaldehyde. Despite the stabilization of 80S ribosomes by formaldehyde‐mediated cross‐linking, stm1Δ cells had fewer 80S ribosomes compared with wild‐type cells (Fig 2E and F). These results suggest that Stm1 is required at least for the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes.

Figure 2. Stm1 forms vacant 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition.

-

A–DPolysome profiles of wild‐type (wt) and stm1Δ cells with (A–C) or without (D) CHX treatment under nutrient‐rich conditions (A, D), with rapamycin treatment for 1 h (B), or under nitrogen starvation for 1 h (C) using 5–50% sucrose density gradients containing 150 mM KCl. At least three biological replicates are analyzed for each condition.

-

E, FPolysome profiles of formaldehyde cross‐linked wild‐type (wt) and stm1Δ cells using 5–50% sucrose density gradients containing 150 mM KCl (E) or 300 mM KCl (F).

-

GPolysome profiles of stm1Δ cells containing either full‐length or N‐terminally deleted or C‐terminally deleted Stm1 mutants upon nitrogen starvation for 1 h.

-

HBinding of full‐length or deletion mutants of Stm1 across the polysome profile fractions shown in Fig 2E. Nine equal‐volume fractions of each polysome profile were precipitated and analyzed by immunoblot for Stm1 and Rpl3. At least two biological replicates are used for each mutant.

To determine which part of the Stm1 protein is required for the formation of vacant ribosomes, we generated a series of deletions (nonoverlapping deletion of 40–80 amino acids) covering the entire Stm1 protein (Fig EV2A). C‐terminal deletion mutants of Stm1 (lacking amino acids 161–200, 201–240 or the C‐terminal residues 201–273) formed 80S ribosomes upon nitrogen starvation, similar to wild‐type Stm1 (Figs 2G and H, and EV2B and C). However, Stm1 mutants lacking N‐terminal regions (lacking amino acids 2–40, 2–80, 41–80, 81–120) failed to form 80S ribosomes upon nitrogen starvation (Figs 2G and H, and EV2B and C). According to the crystal structure of Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes, residues 9 to 40 of Stm1 occupy the 60S subunit while residues 60 to 141 occupy the 40S subunit (Ben‐Shem et al, 2011). Amino acids 40 to 60 of Stm1 act as a linker between the two ribosomal subunits. Thus, the N‐terminal region of Stm1 is required for the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes.

Figure EV2. Stm1 forms vacant 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition.

- Immunoblot of Stm1 and Actin in stm1Δ cells harboring either vector alone, wild‐type, or various deletion mutants of Stm1 in nutrient‐sufficient conditions.

- Polysome profiles of stm1Δ cells containing various deletion mutants of Stm1 upon nitrogen starvation for 1 h.

- Immunoblot of Stm1 across the polysome profile fractions shown in Fig EV2B. Nine equal‐volume fractions of each polysome profile were precipitated and analyzed by immunoblot for Stm1 and Rpl3. At least two biological replicates for each mutant were analyzed.

- Growth of stm1Δ cells expressing either vector alone, Stm1 to the wild‐type level (YCpSTM1, single‐copy plasmid) or overexpression of Stm1 (YEpSTM1, multi‐copy plasmid) on YPD agar plates with or without rapamycin.

- Immunoblot of Stm1 in stm1Δ, wild‐type, and Stm1‐overexpressed cells.

- Growth of stm1Δ cells containing various deletion mutants of Stm1 on YPD agar plates with or without rapamycin. Plates were incubated for 36 h at 30°C.

Stm1 was reported to be important for survival in the presence of rapamycin (Van Dyke et al, 2006). Consistent with the previous reports, we also observed that deletion and overexpression of Stm1 confer rapamycin hypersensitivity and resistance, respectively (Fig EV2D and E). Stm1 mutants lacking the N‐terminal region could not completely suppress the rapamycin hypersensitivity of stm1Δ cells while C‐terminal mutants could (Fig EV2F). Thus, the N‐terminal region of Stm1, which is involved in dormant ribosome formation, is important for coping with stress upon TORC1 inhibition.

TORC1 phosphorylates and inhibits Stm1

How does TORC1 control the interaction of Stm1 with 80S ribosomes? To determine whether Stm1 is regulated by TORC1 via phosphorylation, we performed a phosphoproteomic analysis of total extracts and immunoprecipitated Stm1‐GFP from rapamycin‐treated and ‐untreated yeast cells (Fig EV3A and B). This revealed that several residues in Stm1 are phosphorylated, of which S32, S41, S45, S55, S73, T181, and T218 were significantly less phosphorylated upon rapamycin treatment. Interestingly, in the crystal structure of Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes, serines 41, 45, and 55 are in the Stm1 linker region spanning the space between the 40S and 60S subunits (Ben‐Shem et al, 2011). Furthermore, these three serines fall within the N‐terminal region of Stm1 that mediates formation of dormant 80S ribosomes (Fig EV3C). Hence, we hypothesize that phosphorylation at these sites plays a particularly important role in the regulation of Stm1.

Figure EV3. TORC1 phosphorylates Stm1.

- Relative phosphorylation of Stm1 identified from phosphoproteomic analysis of yeast cells treated with or without rapamycin for 2 h. Four biological replicates are used and analyzed by multiple unpaired t‐tests. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

- Relative phosphorylation of Stm1 identified by mass spectrometry. Stm1‐GFP was pulled down from yeast cells treated with or without rapamycin for 1 h and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis. Two biological replicates were used.

- Analysis of the structure of Stm1 bound to 80S ribosome. The distance (in Å) between serine 41 of Stm1 with its surrounding ribosomal component and serine 55 of Stm1 with its surrounding ribosomal component is shown in dashed line. Stm1 is shown in red, three serines are shown as sticks, 18S rRNA is shown in orange, 25S rRNA is shown in wheat color and ribosomal proteins in cyan.

- Polysome profiles of stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells under control conditions.

- Growth of stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells on YPD agar plates with or without rapamycin. Plates were incubated for 48 h at 30°C.

To assess whether TORC1 directly phosphorylates Stm1, we performed an in vitro kinase assay using recombinant mammalian TORC1 (mTORC1) and Stm1. mTORC1 phosphorylated wild‐type Stm1 (Fig 3A). Serine‐to‐alanine mutation of the three serines in the Stm1 linker region (Stm1AAA, S41A/S45A/S55A) reduced mTORC1‐mediated phosphorylation of Stm1 (Fig 3A and B). We note that the Stm1AAA mutant could still be phosphorylated by mTORC1, likely at other serine residues identified in our phosphoproteomic analysis (Fig EV3A). Thus, Stm1 is directly phosphorylated by TORC1 in vitro.

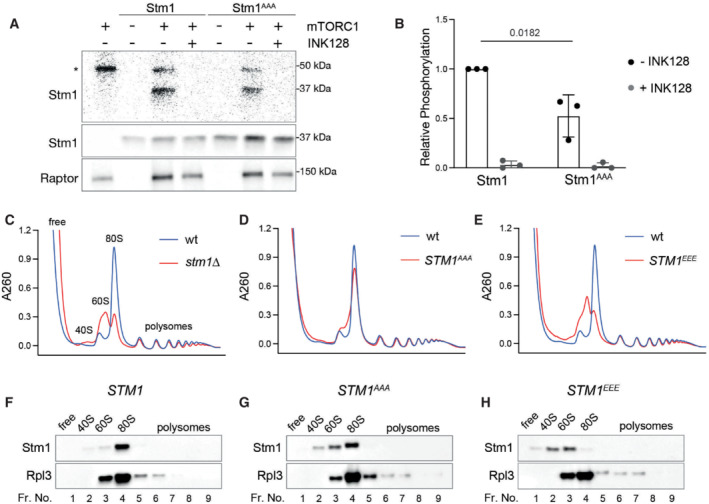

Figure 3. TORC1 phosphorylates and inhibits Stm1.

-

A, BIn vitro kinase assay (A) and its quantitation (B) using recombinant mTORC1 and recombinant Stm1 or Stm1AAA as a substrate in the presence of 32P‐γ‐ATP. Immunoblots for Stm1 and Raptor are shown. Asterisk indicates the auto‐phosphorylation of a mTORC1 component. INK128 is used as an inhibitor of mTOR. Minimum of three replicates are used for statistical analysis by unpaired t‐test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

-

CPolysome profiles of wild‐type and stm1Δ cells under nitrogen starvation for 1 h.

-

DPolysome profiles of wild‐type and STM1 AAA cells under nitrogen starvation for 1 h.

-

EPolysome profiles of wild‐type and STM1 EEE cells under nitrogen starvation for 1 h.

-

F–HImmunoblots for Stm1 and Rpl3 from the ribosomal fractions obtained from wild‐type (F), STM1 AAA (G), and STM1 EEE (H) cells under nitrogen starvation for 1 h.

To elucidate the role of TORC1‐mediated Stm1 phosphorylation in the formation of dormant ribosomes, we analyzed polysome profiles of stm1Δ cells expressing either phospho‐deficient (Stm1AAA) or phospho‐mimetic (Stm1EEE, S41E/S45E/S55E) Stm1. Rapamycin‐treated STM1 AAA cells formed 80S ribosomes like wild‐type cells (Fig 3D, F and G). However, STM1 EEE cells, like stm1Δ cells, accumulated 40S and 60S subunits and were thus defective in forming 80S ribosomes, upon rapamycin treatment (Fig 3C, E and H). These results suggest that TORC1‐mediated phosphorylation of at least the linker region of Stm1 inhibits formation of dormant, Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes. The polysome profiles of rapamycin‐untreated, Stm1AAA‐ and Stm1EEE‐expressing cells were similar, ruling out a role for Stm1 in translation or ribosome biogenesis in normally growing cells (Fig EV3D). Furthermore, phospho‐mimetic Stm1EEE, unlike Stm1AAA, did not suppress the rapamycin hypersensitivity of stm1Δ cells (Fig EV3E). Thus, formation of dormant 80S ribosomes by dephosphorylated Stm1 is important for cell survival under stress.

Stm1 protects ribosomes from proteasomal degradation

Stm1, as a preservation factor, was reported to prevent ribosome degradation in long‐term stationary phase cells (Van Dyke et al, 2013). Thus, we examined the effect of long‐term rapamycin treatment (24 h) on the ribosome content of cells in which Stm1 expression is altered. Deletion or overexpression of Stm1 had no effect on ribosome levels in the absence of rapamycin, compared with wild‐type (Fig EV4A). In the presence of rapamycin, stm1Δ cells contained fewer total 40S and 60S subunits, compared with control cells (Fig EV4B). Cells overexpressing Stm1 contained more ribosomes compared with control cells (Fig EV4B). Importantly, the level of ribosomes in different conditions was confirmed by immunoblotting for Rpl3 (Fig EV4C). These findings support the observation of Van Dyke et al (2013) that Stm1 is a ribosome preservation factor.

Figure EV4. Stm1 preserves ribosomes under TORC1‐inhibited conditions.

-

A, BRibosomal subunit profiles of stm1Δ cells containing no (+vector), wild‐type (+YCpSTM1), or overexpressed (+YEpSTM1) levels of Stm1 without (A) or with (B) rapamycin treatment for 24 h. For the ribosomal subunit profile analyses, the cell extracts were treated with 50 mM EDTA and separated on 5–25% sucrose density gradients.

-

CImmunoblot of Rpl3 in stm1Δ cells containing no (+vector), wild‐type (+YCpSTM1), or overexpressed (+YEpSTM1) levels of Stm1 along with or without rapamycin treatment for 24 h.

-

DRibosome content in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells starved for nitrogen for 24 h, measured from ribosomal subunit profiles. Minimum of five biological replicates are used for multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

E, FImmunoblot (E) and the quantification (F) of Rpl3 in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells under nitrogen starvation for 24 h. At least six biological replicates are subjected to statistical analysis using multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

G, HRibosomal subunit profiles (G) and quantification of relative ribosome content (H) of stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells under nutrient‐sufficient conditions. Minimum three biological replicates are used for multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

IQuantification of Rpl3 in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells under nutrient‐sufficient conditions. Minimum five biological replicates are used for multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

J–LImmunoblot of Rpl24‐GFP and free GFP (J), quantification of total GFP relative to Pgk1 (K), and free GFP relative to Rpl24‐GFP (L) in wild‐type and stm1Δ cells treated with rapamycin for 16 and 24 h. At least three replicates are used for multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

MImmunoblots for ubiquitylation in the supernatant and ribosomal pellet obtained from wild‐type and stm1Δ cells starved for nitrogen (24 h) along with or without puromycin treatment. Immunoblots for Stm1, Rpl3, Pgk1, and puromycin are also shown.

-

N, OImmunoblot for ubiquitin (N) and its quantification (O) after pull‐down of Rpl24‐GFP in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells treated with rapamycin for 24 h along with or without bortezomib for 8 h (in pdr5Δ background). Minimum of four replicates are quantified and analyzed using multiple unpaired t‐tests.

Data information: Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Next, we investigated the role of TORC1‐mediated Stm1 phosphorylation on ribosome preservation. Similar to the stm1Δ, STM1 EEE cells exhibited lower ribosome content compared with wild‐type or STM1 AAA cells, upon long‐term rapamycin treatment (Fig 4A and B). stm1Δ and STM1 EEE cells also showed lower ribosome content upon long‐term (24 h) nitrogen starvation (Fig EV4D). Immunoblot analysis also showed reduced levels of ribosomal protein Rpl3, in both stm1Δ and STM1 EEE cells, upon rapamycin treatment (Fig 4C and D) or nitrogen starvation (Fig EV4E and F). Analysis of polysome profiles and Rpl3 levels of normally growing cells revealed no change in ribosome content, regardless of the status of Stm1 (Fig EV4G–I). These data suggest that dephosphorylation of Stm1 upon TORC1 inhibition, and Stm1's subsequent formation of dormant 80S ribosomes, are important for the long‐term preservation of ribosomes.

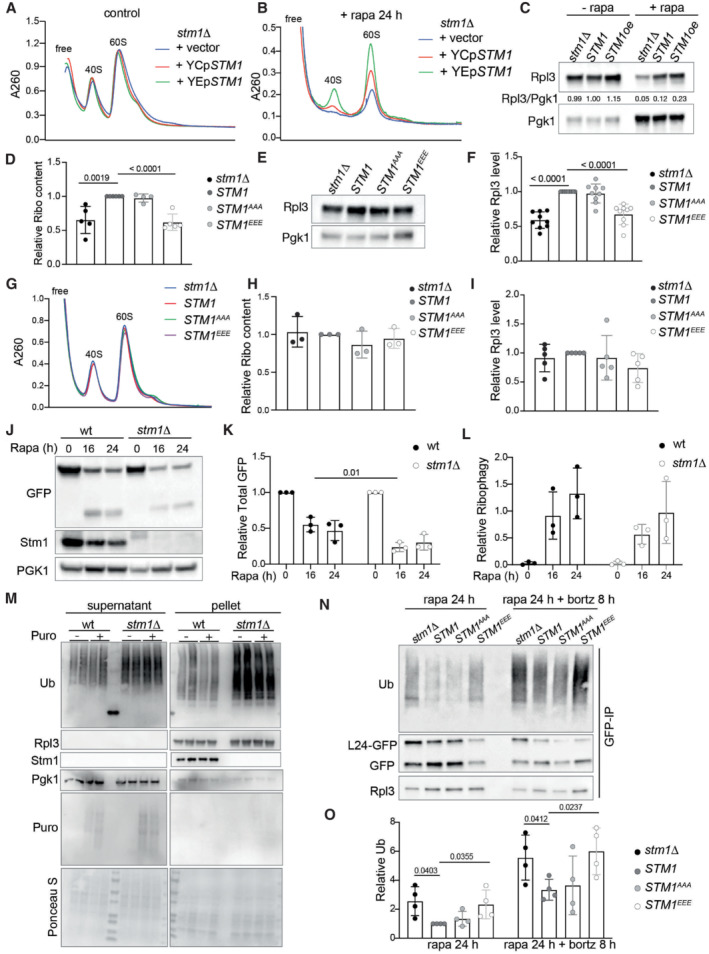

Figure 4. Stm1 protects ribosomes from proteasomal degradation.

-

A, BRibosomal subunit profiles (A) and quantitation of ribosome content (B) of stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells treated with rapamycin for 24 h. For the ribosomal subunit profile analyses, the cell extracts were treated with 50 mM EDTA and separated on 5–25% sucrose density gradients. At least five biological replicates are used for the calculation of P‐values from multiple unpaired t‐tests indicated in the graphs.

-

C, DImmunoblot (C) and the quantification (D) of Rpl3 in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells treated with rapamycin for 24 h. At least six biological replicates are subjected to statistical analysis using multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

E–GImmunoblot of Rpl24‐GFP and free GFP (E), quantification of total GFP relative to Pgk1 (F), and free GFP relative to Rpl24‐GFP (G) in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells treated with rapamycin for 24 h. At least six biological replicates are subjected to statistical analysis using multiple unpaired t‐tests. (s.e. for short exposure; l.e. for long exposure).

-

H, IImmunoblot for ubiquitin in the supernatant and ribosomal pellet (H) obtained from stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells treated with rapamycin for 24 h. Immunoblots for Stm1 and Rpl3 are shown as controls. Quantification of ribosomal ubiquitylation (I) relative to wild‐type is shown. The ribosome pellets were obtained using a 1 M sucrose cushion. At least six biological replicates are subjected to statistical analysis using multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

J, KImmunoblot (J) and the quantification (K) of Rpl3 in wild‐type and stm1Δ cells without rapamycin, or with rapamycin for 24 h along with or without bortezomib treatment for 8 h. At least six biological replicates are subjected to statistical analysis using multiple unpaired t‐tests.

Data information: The respective P‐values are indicated in the figure. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

In yeast, upon TORC1 inhibition, ribosomes are degraded mainly via ribophagy (Kraft et al, 2008). Thus, we tested whether ribosomes in rapamycin‐treated stm1∆ cells undergo increased degradation via ribophagy. Ribophagy can be monitored by tagging ribosomal proteins with green fluorescent protein (GFP) and assaying the accumulation of free GFP, which is resistant to vacuolar proteases (Kraft et al, 2008). Upon long‐term rapamycin treatment (24 h), stm1Δ and STM1 EEE cells contained less Rpl24‐GFP and, surprisingly, also less free GFP, compared with control cells (Figs 4E and F, and EV4J and K). However, there was no difference in the ratio of free GFP to Rpl24‐GFP in wild‐type, stm1Δ, and STM1 EEE cells (Figs 4G and EV4L), suggesting that the enhanced degradation of ribosomes in rapamycin‐treated stm1Δ cells is not due to ribophagy.

An alternative pathway for ribosomal degradation is the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway (An & Harper, 2020). Indeed, analysis of poly‐ubiquitin in isolated ribosomes from long‐term rapamycin‐treated cells revealed increased ribosome poly‐ubiquitylation in stm1∆ cells compared with controls (Fig 4H and I). STM1 EEE cells, but not STM1 AAA cells, also showed increased ribosome poly‐ubiquitylation upon long‐term rapamycin treatment (Fig 4H and I). These data suggest that ribosomes are subjected to increased ubiquitylation in the absence of ribosomal dormancy, following TORC1 inhibition. To rule out that the increased ubiquitylation of ribosomes is due to the ubiquitylation of nascent polypeptides, we treated cells with puromycin for 15 min to release nascent polypeptides. The puromycin treatment did not reduce the amount of ubiquitin in ribosomal pellets, further supporting increased poly‐ubiquitylation of ribosomes in stm1Δ cells (Fig EV4M). To investigate further whether ribosomes are degraded by the proteasome during rapamycin treatment, we treated cells with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. This experiment was performed in a strain lacking Pdr5 (a multidrug efflux pump) to make yeast cells responsive to bortezomib (Collins et al, 2010). GFP pull‐down of ribosomes using Rpl24‐GFP revealed increased ribosomal ubiquitylation in stm1∆ and STM1 EEE cells upon long‐term rapamycin treatment (Fig EV4N and O). Bortezomib further enhanced the poly‐ubiquitylation of ribosomes in stm1∆ and STM1 EEE cells. Furthermore, bortezomib increased Rpl3 levels in rapamycin‐treated stm1∆ and wild‐type cells (Fig 4J and K). These results suggest that Stm1, in addition to mediating the formation of dormant ribosomes, preserves 80S ribosomes by preventing their ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation.

TORC1 activates dormant ribosomes by inhibiting Stm1

The above findings suggest that cells maintain a pool of dormant ribosomes during long‐term starvation, possibly to kick‐start growth upon re‐feeding. Similar to a previous study (Van Dyke et al, 2013), we observed that the resumption of translation upon re‐feeding of starved cells was delayed in stm1Δ cells (Fig EV5A). Thus, Stm1‐mediated preservation of ribosomes under starvation is required for efficient translation recovery upon re‐feeding. To investigate whether TORC1‐mediated phosphorylation of Stm1 promotes the resumption of translation, we analyzed translation in re‐fed wild‐type, STM1 AAA , or STM1 EEE mutant cells. Wild‐type cells resumed translation within 10 min of nutrient replenishment, while both STM1 AAA and STM1 EEE cells required > 30 min for the resumption of translation, as measured by puromycin incorporation (Fig 5A and B). Delayed recovery of translation in STM1 EEE and stm1Δ cells correlated with reduced ribosome content (Fig EV4D and E). Importantly, STM1 AAA cells displayed delayed recovery of translation despite normal ribosome levels (Fig EV4D and E). Under nutrient‐sufficient conditions, manipulation of Stm1 did not affect translation (Fig EV5B and C). Altogether, this suggests that TORC1‐mediated phosphorylation of Stm1 at serines 41, 45, and 55 is required for efficient activation of dormant ribosomes and stimulation of translation during recovery from starvation.

Figure EV5. Stm1 is required for translation recovery.

-

APuromycin incorporation in wild‐type and stm1Δ cells subjected to nitrogen starvation for 24 h and restimulated with amino acids for 30 min. Immunoblots for phospho‐Rps6, Stm1, and Pgk1 are shown. Three biological replicates are shown for each condition.

-

B, CPuromycin incorporation (B) and its quantification (C) in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells under nutrient‐sufficient conditions. Immunoblots for puromycin, Stm1, and Pgk1 are shown. Six biological replicates are analyzed by multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

D, EGrowth of germinated spores (D) and its quantification (E) upon dissection of tetrads obtained from diploid wild‐type and stm1Δ/stm1Δ strains on YPD agar media after 48 h of incubation. At least 24 replicates are analyzed by unpaired t‐test. (Each row shows four spores from individual tetrads of wild‐type and stm1Δ, which are labeled as t1, t2, etc.).

-

FImmunoblots for Rpl3, Stm1, and Pgk1 in diploid wild‐type (TB50a), heterozygous stm1Δ, and homozygous stm1Δ strains grown in sporulation media.

-

G, HGrowth of germinated spores (G) and its quantification (H) upon dissection of tetrads obtained from diploid control (RPL24‐GFP) and stm1Δ RPL24‐GFP cells on YPD agar media after 30 h of incubation. At least 28 replicates are analyzed by unpaired t‐test.

-

I, JImmunoblots of SERBP1, RPS6, and RPL7a across the polysome fractions of HEK293T cells treated with DMSO or INK128 for 1 h. Polysome profiles were analyzed on 150 mM KCl (I) or 50 mM KCl (J) containing sucrose density gradients.

-

KImmunoblots of SERBP1, phospho‐RPS6 (S240/244), and RPS6 in HEK293T cells treated with control‐ or SERBP1‐siRNA, with or without INK128 for 1 h.

-

LQuantification of ribosome subunit analysis of HEK293T cells treated with control sgRNA (sgCtrl) or SERBP1 sgRNA (sgSERBP1) under normal conditions (Related to Fig 6F). Minimum of four biological replicates are analyzed for each condition by unpaired t‐test.

-

MRelative phosphorylation of SERBP1 identified from phosphoproteomic analysis of HEK293 cells treated with or without INK128 for 2 h. Data were analyzed by multiple unpaired t‐tests.

Data information: Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Figure 5. TORC1 activates dormant ribosomes by inhibiting Stm1.

-

A, BPuromycin incorporation (A) and its quantification (B) in stm1Δ, wild‐type, STM1 AAA , and STM1 EEE cells starved of nitrogen for 24 h and restimulated with amino acids (+N) for 10, 20, or 30 min. Immunoblots for puromycin, Stm1, Rpl3, and Pgk1 are shown. Relative puromycin incorporation for at least five biological replicates is subjected to multiple unpaired t‐tests.

-

CGermination efficiency of spores upon dissection of tetrads (schematic in upper panel) from diploid wild‐type and stm1Δ cells on YPD agar media after 6 h of incubation. Minimum of four replicates are used for the unpaired t‐test.

-

D, ERepresentative fluorescent microscopic images for expression of Rpl24‐GFP (D) and its intensity quantification (E) in tetrads of control (RPL24GFP) and stm1Δ RPL24GFP cells (n = 100, each). Experiments are performed at least three times. Statistical analysis is done by unpaired t‐test.

Data information: Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

We investigated the significance of Stm1‐mediated ribosome preservation in another physiological context. In response to long‐term nitrogen and glucose starvation, diploid yeast cells undergo meiosis and form asci containing four haploid spores, equivalent to gametes, which then germinate upon nutrient replenishment. We examined the role of the Stm1‐mediated preservation of ribosomes in spore germination. In particular, we examined the germination of spores derived from stm1Δ/stm1Δ diploid cells (Fig 5C). 90% of wild‐type spores but only 25% of stm1Δ spores germinated within 6 h of nutrient stimulation (Fig 5C). This was not due to the reduced viability of stm1∆ spores as essentially all spores eventually germinated to form small colonies after 2 days of incubation (Fig EV5D and E). The level of ribosomal protein Rpl3 was decreased in spores derived from stm1∆/stm1Δ cells, compared with spores from wild‐type diploid cells (Fig EV5F), suggesting a loss of ribosomes in stm1∆ spores. To confirm a reduction in ribosomes in stm1∆ spores, we monitored the level of GFP‐tagged Rpl24 in spores from stm1Δ/stm1Δ diploid cells. The level of Rpl24‐GFP was significantly decreased in stm1∆ spores, compared with wild‐type spores (Figs 5D and E, and EV5G and H). These findings suggest that Stm1‐mediated preservation of ribosomes is required for efficient germination of dormant spores.

Regulation of ribosome dormancy by TORC1 is evolutionarily conserved

The interaction of Stm1 with ribosomes appears to be conserved in eukaryotes as vacant human 80S ribosomes contain SerpineE1 mRNA binding protein (SERBP1), an ortholog of yeast Stm1 (Anger et al, 2013; Brown et al, 2018). We investigated whether mTORC1 affects the interaction of SERBP1 with 80S ribosomes. In polysome profiles from proliferating HEK293T cells, SERBP1 was found preferentially in the 40S fraction but also in the 60S, 80S, and low molecular weight polysome fractions (Fig 6A). Inhibition of mTOR with INK128 caused SERBP1 to accumulate in the 80S fraction (Figs 6B and EV5I). Increasing the amount of 80S ribosomes by harringtonine treatment, which traps mRNA‐bound 80S initiation complexes, did not increase the amount of SERBP1 in the 80S fraction (Fig 6C). These results suggest that SERBP1, like Stm1, forms a complex only with mRNA‐free 80S ribosomes. A previous study reported an interaction of SERBP1 mainly with translating ribosomes (polysomes; Muto et al, 2018). As observed with Stm1 (see above), the interaction of SERBP1 with polysomes was dependent on the concentration of KCl (50 vs. 150 mM), again suggesting the interaction was nonspecific (Fig EV5I and J).

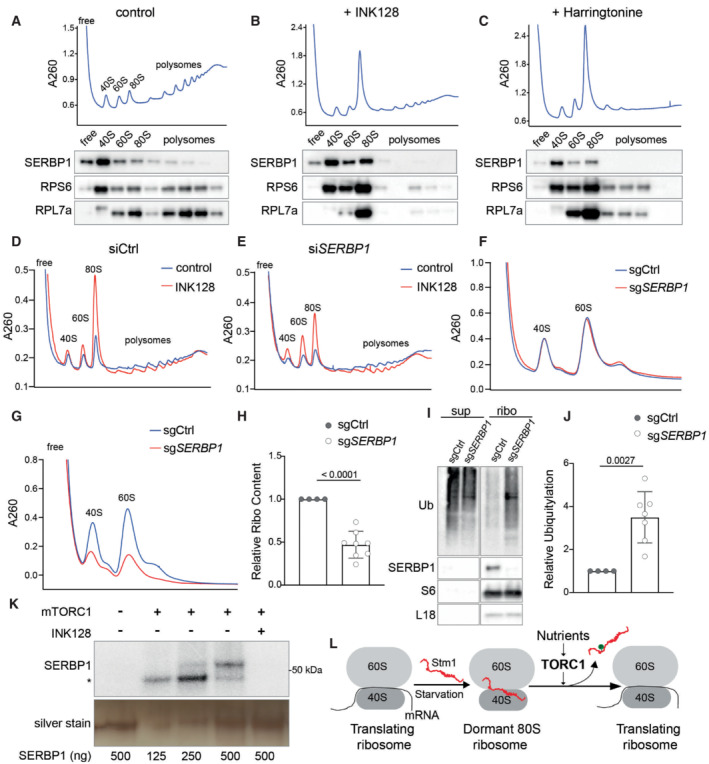

Figure 6. SERBP1 preserves ribosomes in human cells.

-

A–CPolysome profile and immunoblotting of SERBP1, RPS6, and RPL7a across the polysome fractions of HEK293T cells treated with DMSO (A), INK128 (B), or harringtonine (C) for 1 h. Polysome profiles were performed using 5–50% sucrose density gradients containing 150 mM KCl.

-

D, EPolysome profile analyses of HEK293T cells treated with control siRNA (siCtrl) (D) or SERBP1 siRNA (siSERBP1) (E), with or without INK128 treatment for 1 h. Polysome profiles were performed using 5–50% sucrose density gradients containing 150 mM KCl.

-

FRibosome subunit analysis of HEK293T cells treated with control sgRNA (sgCtrl) or SERBP1 sgRNA (sgSERBP1) under normal conditions. Minimum of four biological replicates are analyzed.

-

G, HRibosome subunit analysis (G) and its quantification (H) of HEK293T cells treated with control sgRNA (sgCtrl) or SERBP1 sgRNA (sgSERBP1) along with INK128 treatment for 48 h. At least four biological replicates are analyzed by unpaired t‐test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

-

I, JImmunoblot for ubiquitin (I) and its quantification (J) in the supernatant and ribosomal pellet obtained from HEK293T cells treated with control sgRNA (sgCtrl) or SERBP1 sgRNA (sgSERBP1) along with INK128 treatment for 48 h. At least four biological replicates are analyzed by unpaired t‐test. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

-

KIn vitro kinase assay using recombinant mTORC1 and purified SERBP1 as a substrate in the presence of 32P‐γ‐ATP. Asterisk indicates the auto‐phosphorylation of a mTORC1 component. INK128 is used to inhibit mTOR.

-

LModel showing the TORC1‐mediated regulation of dormant 80S ribosome formation and translation recovery upon re‐feeding via Stm1/SERBP1.

Knockdown of SERBP1 in HEK293T cells using siRNAs showed no significant change in polysome profile under normal conditions in which mTORC1 is active (Figs 6D and E, and EV5K). However, SERBP1 depletion decreased 80S ribosomes and increased 40S and 60S subunits compared with control cells, upon mTOR inhibition by INK128 (Figs 6D and E, and EV5K). Thus, similar to Stm1, SERBP1 forms dormant 80S ribosomes upon mTOR inhibition. To investigate the effect of SERBP1 on ribosome preservation, we deleted SERBP1 using CRISPR sgRNAs and analyzed ribosome levels. In proliferating cells, SERBP1 deletion had no effect on ribosome content compared with control cells (Figs 6F and EV5L). Upon long‐term inhibition (48 h) of mTOR by INK128 treatment, SERBP1 deleted cells showed a significant reduction in ribosome content (Fig 6G and H) and a significant increase in ribosome poly‐ubiquitylation (Fig 6I and J), compared with control cells. Thus, SERBP1‐mediated formation of dormant 80S ribosomes is important for the protection of ribosomes in human cells.

We examined whether SERBP1, like Stm1, is regulated by mTORC1. To investigate whether SERBP1 is directly phosphorylated by mTORC1, we performed an in vitro kinase assay with recombinant mTORC1 and SERBP1. mTORC1 phosphorylated SERBP1 in an INK128‐sensitive manner, suggesting that SERBP1 is an mTORC1 substrate (Fig 6K). Furthermore, to identify mTOR‐dependent phosphorylation sites on SERBP1, we performed a phosphoproteomic analysis of INK128‐treated and ‐untreated HEK293 cells. Inhibition of mTOR caused a significant reduction in the phosphorylation of SERBP1 at serine 199 and threonine 226 (Fig EV5M). We also observed a trend for reduced phosphorylation at serine 25, 197, and 234 residues (Fig EV5M). The above results suggest that SERBP1 is phosphorylated by mTORC1. Thus, the regulation of ribosomal dormancy via mTORC1‐mediated phosphorylation of a ribosome preservation factor is evolutionarily conserved.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that eukaryotic cells utilize Stm1/SERBP1 to inactivate and preserve ribosomes in response to TORC1 inhibition or nutrient deprivation. We further show that the nutrient sensor TORC1 controls Stm1/SERBP1 in an evolutionarily conserved manner. Under nutrient‐sufficient conditions, TORC1 phosphorylates Stm1/SERBP1 to prevent it from forming a complex with the 80S ribosome. Upon TORC1 inhibition, dephosphorylated Stm1/SERBP1 forms nontranslating, dormant 80S ribosomes that are protected from proteasome‐mediated degradation (Fig 6L).

The accumulation of nontranslating 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition or nutrient deprivation was previously reported but not well understood (Barbet et al, 1996; Larsson et al, 2012; Gandin et al, 2014; Muller et al, 2019). Based on conventional wisdom, one would expect an accumulation of free 40S and 60S subunits due to the inhibition of translation initiation. Our study suggests that the accumulation of 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition is due to the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes by Stm1/SERBP1. In dormant 80S ribosomes, Stm1/SERBP1 occupies the mRNA tunnel, thereby preventing translation and “gluing” the two subunits together (Jenner et al, 2012; Anger et al, 2013). In vitro translation experiments showed that Stm1 represses translation via its N‐terminal region (Balagopal & Parker, 2011; Hayashi et al, 2018). We show that the N‐terminal 120 residues of Stm1 are important for the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes upon TORC1 inhibition. We note that the recombinant Stm1 protein used in previous in vitro experiments was purified from Escherichia coli and therefore not in the inhibited, phosphorylated state. Thus, Stm1/SERBP1 prevents inappropriate translation initiation under TORC1‐inhibited conditions, in addition to preserving nontranslating ribosomes from proteasomal degradation (see below).

mTORC1 promotes translation at many levels. It stimulates ribosome biogenesis and tRNA synthesis (Mayer & Grummt, 2006). It promotes translation initiation by phosphorylating and inhibiting eIF4E‐binding proteins (4EBPs), thereby allowing the assembly of the eIF4F complex (Gingras et al, 2004; Proud, 2019). TORC1 also promotes translation initiation by phosphorylating initiation factor eIF4B (Ma & Blenis, 2009). Our data suggest that TORC1 also activates translation via phosphorylation and inhibition of Stm1. Analysis of the structure of the Stm1‐bound 80S ribosome suggests that phosphorylation of at least serines 41 and 55 by TORC1 would sterically hinder Stm1 in binding 80S ribosomes (Fig EV3C). Thus, activation of dormant ribosomes via phosphorylation of Stm1 is yet another mechanism by which TORC1 promotes translation, underscoring the importance of translation as a readout of TORC1 signaling in the control of cell growth.

Our proposal that Stm1 forms dormant 80S ribosomes invokes the necessity of an additional mechanism to recycle 40S and 60S subunits during the resumption of translation. A previous study showed that glucose starvation, a condition where TORC1 is known to be inhibited, causes an accumulation of 80S ribosomes. During recovery from glucose starvation, Dom34 (duplication of multi‐locus region 34) and Hbs1 (Hsp70 subfamily B suppressor 1) split vacant 80S ribosomes to recycle the two subunits (Pisareva et al, 2011; van den Elzen et al, 2014). Agreeing with our observation that Stm1 is required for the formation of dormant 80S ribosomes, in the absence of Stm1, Dom34 and Hbs1 are dispensable for the resumption of translation (van den Elzen et al, 2014). Another study demonstrated that overexpression of Stm1 is toxic in strains lacking Dom34 (Balagopal & Parker, 2011), suggesting that Stm1 and Dom34 have opposing functions. However, a recent in vitro study concluded that Stm1‐bound 80S ribosomes are resistant to splitting by Dom34‐Hbs1 (Wells et al, 2020). Since this recent in vitro study lacked TORC1‐mediated phosphorylation, we propose that TORC1‐dependent Stm1 phosphorylation might be assisting in the recycling of dormant 80S ribosomes by Dom34 and Hbs1.

In yeast, upon TORC1 inhibition, ribosomes are considered to be degraded mainly via ribophagy (Kraft et al, 2008). However, in the absence of Stm1/SERBP1, we observed the enhanced proteasome‐mediated degradation of ribosomes with no effect on ribophagy. Furthermore, the inhibition of proteasomal degradation upon rapamycin treatment partly prevented ribosome turnover, in both wild‐type and stm1Δ cells. This suggests that upon TORC1 inhibition, ribosomes are degraded by both the proteasome and ribophagy (Kraft et al, 2008). A recent study in mammalian cells showed that proteasomal degradation, rather than ribophagy, is the major mechanism of ribosome degradation upon mTOR inhibition (An et al, 2020). How does Stm1/SERBP1 protect dormant 80S ribosomes from proteasomal degradation? One possible explanation is that the interface of the two ribosomal subunits, which is masked in the 80S ribosome, is recognized by ubiquitin ligases. It will be of interest to identify the mechanisms and the ubiquitin ligases that mediate ubiquitylation and the degradation of ribosomal subunits upon nutrient starvation. Interestingly, the levels of Stm1 also decrease upon long‐term TORC1 inhibition. Whether the degradation of Stm1 and ribosomal proteins is co‐regulated needs further investigation.

TORC1 in yeast phosphorylates Stm1 to stimulate protein synthesis in response to nutrients, in vegetatively growing cells or germinating spores. mTORC1 similarly phosphorylates the Stm1 ortholog SERBP1 in mammalian cells. Although we did not investigate the physiological context in which mTORC1 regulates SERBP1, we speculate that this regulation could be important in the survival and activation of quiescent cells such as stem cells, immune cells, and gametes.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial cells

DH5α E. coli cells were used to generate all the plasmid constructs used in the study. DH5α was grown in LB medium at 37°C.

Yeast cells

Yeast strains used in this study are mainly generated using Tb50a background (Beck & Hall, 1999). Yeast cells are usually grown in YPD media at 30°C. For the inhibition of TORC1, liquid cultures are treated with 200 nM rapamycin (prepared in 90% ethanol 10% Tween 20) or YPD agar plates containing 4–6 ng/ml rapamycin. For the nitrogen starvation experiment, cells are grown in YPD to 0.6–0.8 OD600 and then washed once with sterile water and resuspended in synthetic media (containing yeast nitrogen base without ammonia and glucose) for the indicated time points. For restimulation of starved cells, 10× amino acid mix is used for the mentioned time points. Strains with deletion and chromosomal tags were generated in the background of TB50a (MATa leu2‐3,112 ura3‐52 trp1 his3 rme1) using homologous recombination. The strains used in the study are listed in Table EV1. The recombinant plasmids used in this study are mentioned in Table EV2. Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table EV3.

Human cell lines

HEK293T and HEK293 cells were obtained from ATCC. Cells were cultured in DMEM with high glucose supplemented with 10% Fetal bovine serum (FBS), glutamine, and Pen/Strep and incubated at 37°C, and 5% CO2. siRNA‐mediated knockdown and sgRNA‐mediated knock‐outs were performed using JetPrime transfection reagent.

Polysome profile analysis

The yeast cells were grown to 0.6 to 0.8 OD600 and treated with 100 μg/ml CHX for 2 min and harvested by centrifugation 2,000 g for 2 min at 4°C. The cell pellets were washed once with PBS containing CHX and once with the lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X100, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml CHX, 0.1 mM PMSF, 40 U/ml RNasein plus) and resuspended in lysis buffer. Cells were lysed by bead‐beating method using vibrax for 15 min and the lysates were harvested. Fifty to 100 μg of total RNA was loaded onto TH641 tubes containing 5–50% sucrose density gradient (in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml CHX) and spun for 2 h at 221,777 g. For the low salt conditions, 50 mM KCl was used, while for high salt, 300 or 800 mM KCl was used. For analyses of ribosome content, 100 μg of cell extract was treated with 50 mM EDTA and then loaded onto 5–25% sucrose density gradient containing 50 mM KCl and spun for 4 h at 221,777 g using TH641 rotor (Sorvall). For formaldehyde cross‐linking of the ribosomes, cells grown to 0.6 OD600 were starved for nitrogen for 1 h and then treated with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min. Cross‐linking was quenched using 0.1 M glycine and the cell lysates were prepared and analyzed as mentioned above using 5–50% sucrose density gradient containing either 300 or 800 mM KCl. The cell lines were lysed by hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 1.5 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X100, 0.1% Sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM DTT, 100 μg/ml CHX, EDTA free Protease Inhibitor, 40 U/ml RNasein plus), incubated at 4°C for 15 min and the KCl concentration is adjusted to 100 mM prior to the centrifugation to obtain cell extract. The gradient conditions used were similar to the yeast lysates. After centrifugation, the gradients were analyzed at an absorbance of 260 nm using BIOCOMP fraction analyzer and 9 or 14 equal‐volume fractions were collected. For the immunoblot of the fractions, individual fractions were precipitated by 10% TCA, acetone washed twice, and resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer (36% Glycerin, 15% 2‐mercaptoethanol, 3.6% SDS, 90 mM Tris–pH 6.8, 0.07% Bromophenol Blue). For the mass spectrometric analysis, 10% TCA‐precipitated fractions were washed with acetone twice and resuspended in urea buffer compatible with mass spectrometry (see mass spec protocol). For the ribosome isolation using a sucrose cushion, cell lysates were layered over 0.6 ml of 1 M sucrose solution in TLA120.1 tube and centrifuged at 244,413 g for 2 h. The supernatant and the pellets were analyzed by immunoblot.

Translation efficiency assay

For puromycin incorporation assay, yeast cells from specified conditions were treated with puromycin (100 μg/ml) for 15 min at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by 10% TCA (Trichloroacetic acid). The cells were washed with 95% acetone and resuspended in 0.2 M NaOH (with 0.1 mM PMSF) for 10 min at room temperature and lysed with 2× Laemmli buffer at 95°C for 15 min. The lysates were loaded onto 4–20% PAGE gels and immunoblotted for puromycin.

Spore germination analysis

The diploid yeast cells were sporulated using sporulation media. The tetrads were dissected on YPD agar using a micromanipulator. The germination event was monitored microscopically after dissection and the number of spores achieving the 2‐cell stage within 6 h of dissection was counted. For each biological replicate, the germination of 14 spores was monitored. The plates were further incubated at 30°C to monitor colony formation. For the analyses of ribosome content in spores, RPL24 was GFP tagged on both chromosomes and the resultant cells were sporulated and monitored for the expression of GFP in tetrads by fluorescent microscopy.

Immunoprecipitation

Yeast cells were resuspended in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, 1% Triton X100, 1× complete mini‐protease inhibitor, and 1× PhosSTOP (hereafter referred to as IP buffer) and lysed using bead‐beating. Lysates are harvested by centrifugation at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. Protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using BCA assay. For immunoprecipitation of GFP, GFP‐Trap (ChromoTek) was used. Fifty microliter of magnetic beads was incubated with 2 mg of lysate for 3 h at 4°C with gentle rotation. After four times washing with IP buffer without the detergent, the bound GFP‐tagged proteins were eluted with 2× Laemmli buffer and were resolved by SDS–PAGE for subsequent immunoblot analysis.

For purification of recombinant Stm1 and Stm1AAA, 0.6 OD600 cultures of BL21 strains containing either pGEX6P‐GST‐Stm1 or pGEX6P‐GST‐Stm1AAA were induced with 100 mM IPTG for 3 h and lysed by sonication in lysis buffer containing PBS, 1% Triton X100 and 1 mM PMSF. Cell lysates were incubated with GST beads for 3 h and washed five times with PBS. The beads were incubated with 1× Kinase assay buffer containing HRV 3C protease. The cleaved Stm1 was collected from the supernatant.

In vitro kinase assay

Recombinant SERBP1 (Origene) or Stm1 or Stm1AAA were incubated with 100 nM of purified mTORC1 (Timm Maier laboratory, Biozentrum) in a kinase assay buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM MnCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 0.0025% Tween 20, 2.5 mM DTT, 10 μM ATP, 4 μCi 32P‐γ‐ATP) with DMSO or INK128 200 nM. The reaction is incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction is stopped using 1× Laemmli buffer and boiled at 95°C for 10 min. The proteins were resolved using SDS–PAGE and either directly exposed to radiographic films or transferred to a membrane and then exposed to radiographic films.

Analysis of ribophagy

C‐terminal GFP tagging of Rpl24 in TB50a stm1Δ background was done according to the standard procedure. TB50a stm1Δ RPL24‐GFP were transformed with either vector alone (YCplac33), STM1, STM1 AAA , or STM1 EEE . These strains were overnight grown in SD‐Ura medium and sub‐cultured into YPD medium. Cells grown to 0.6 OD600 were treated with 200 nM rapamycin. The cells were harvested at various time points and precipitated by 10% TCA (Trichloroacetic acid). The cells were washed with 95% acetone and resuspended in 0.2 M NaOH (with 0.1 mM PMSF) for 10 min at room temperature and lysed with 2× Laemmli buffer at 95°C for 15 min. The lysates were loaded onto 4–20% PAGE gels and immunoblotted for GFP.

Analysis of ribosome composition

Yeast cells were grown to 0.5 OD600 and treated with 200 nM rapamycin for 1 h. The preparation of cell extracts and polysome profile were performed as mentioned above. Each polysome profile was collected into 14 equal fractions and precipitated using TCA. The precipitates were acetone washed and resuspended in a resuspension buffer containing 8 M Urea, 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate, and 5 mM TCEP. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and treated with chloroacetamide at a final concentration of 15 mM. After an incubation of 30 min at 37°C, samples were diluted eight times with 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate and sequencing‐grade modified trypsin (1/50, w/w; Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) was added, and proteins were digested for 12 h at 37°C shaking at 300 rpm. Digests were acidified (pH < 3) using TFA and desalted using iST cartridges (PreOmics, Martinsried, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Peptides were dried under vacuum and stored at −20°C. Dried peptides were resuspended in 0.1% aqueous formic acid and subjected to LC–MS/MS analysis using Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Mass Spectrometer. The acquired raw files were imported into the Progenesis QI software. The generated mgf file was searched using MASCOT against a Saccharomyces cerevisiae database. The database search results were filtered using the ion score to set the false discovery rate (FDR) to 1% on the peptide and protein level, respectively, based on the number of reverse protein sequence hits in the dataset. Quantitative analysis results from label‐free quantification were processed using the SafeQuant R package v.2.3.2. to obtain peptide relative abundances.

Phosphoproteomic analysis

For yeast phosphoproteomics, cells were grown in YPD to 0.4 OD600 and treated with 200 nM rapamycin for 2 h. For the phosphoproteomics of HEK293, 90% of confluent cells were treated with DMSO or INK128 for 2 h. The cells were lysed in 2 M Guanidine‐HCl, 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate, 5 mM TCEP, and phosphatase inhibitors by bioruptor. Lysates were incubated for 10 min at 95°C and let to cool down to room temperature followed by the addition of chloroacetamide at a final concentration of 15 mM. After an incubation of 30 min at 37°C, samples were diluted to a final Guanidine‐HCl concentration of 0.4 M using 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer. Proteins were digested by incubation with trypsin (1/100, w/w) for 12 h at 37°C. After acidification using 5% TFA, peptides were desalted using C18 reverse‐phase spin columns according to the manufacturer's instructions, dried under vacuum, and stored at −20°C until further use. Peptide samples were enriched for phosphorylated peptides using Fe(III)‐IMAC cartridges on an AssayMAP Bravo platform as recently described (Post et al, 2017). Phospho‐enriched peptides were resuspended in 0.1% aqueous formic acid and subjected to LC–MS/MS analysis using an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Mass Spectrometer.

The acquired raw files were imported into the Progenesis QI software. The generated mgf file was searched using MASCOT against a human database or a Saccharomyces cerevisiae database. The database search results were filtered using the ion score to set the false discovery rate (FDR) to 1% on the peptide and protein level, respectively, based on the number of reverse protein sequence hits in the datasets. Quantitative analysis results from label‐free quantification were processed using the SafeQuant R package v.2.3.2. (PMID: 27345528, https://github.com/eahrne/SafeQuant/) to obtain peptide relative abundances. This analysis included global data normalization by equalizing the total peak/reporter areas across all LC–MS runs, data imputation using the knn algorithm, summation of peak areas per protein, and LC–MS/MS run, followed by the calculation of peptide abundance ratios.

For the analysis of phosphorylation on immune‐precipitated Stm1 by mass spectrometry, GFP‐tagged Stm1 was pulled down from yeast cells with or without rapamycin treatment using GFP‐Trap and subjected to on‐bead digestion with Trypsin (Soulard et al, 2010). The peptides were purified using C18 columns and analyzed by mass spectrometry.

Author contributions

Sunil Shetty: Conceptualization; validation; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Jon Hofstetter: Investigation. Stefania Battaglioni: Investigation. Danilo Ritz: Investigation; methodology. Michael N Hall: Supervision; project administration; writing – review and editing.

Disclosure and competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Table EV1

Table EV2

Table EV3

PDF+

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Michael W. Van Dyke (Kennesaw State University), Prof. Jonathan R. Warner (Albert Einstein Institute, NY), and Prof. Maurice S. Swanson (University of Florida) for antibodies against Stm1, Rpl3, and Pab1, respectively. We thank Dr. Nikolaus Dietz and Prof. Timm Maier for recombinant mTORC1. SS was supported by EMBO LTF 2016. MNH acknowledges the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 179569 and NCCR RNA and Disease), the Louis Jeantet Foundation, and the Canton of Basel.

The EMBO Journal (2023) 42: e112344

Data availability

Proteomic data have been deposited on ProteomeXChange with accession code PXD037117 (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org/cgi/GetDataset?ID=PXD037117). Other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

- An H, Harper JW (2020) Ribosome abundance control via the ubiquitin‐proteasome system and autophagy. J Mol Biol 432: 170–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H, Ordureau A, Korner M, Paulo JA, Harper JW (2020) Systematic quantitative analysis of ribosome inventory during nutrient stress. Nature 583: 303–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anger AM, Armache JP, Berninghausen O, Habeck M, Subklewe M, Wilson DN, Beckmann R (2013) Structures of the human and drosophila 80S ribosome. Nature 497: 80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe MP, De Long SK, Sachs AB (2000) Glucose depletion rapidly inhibits translation initiation in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 11: 833–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagopal V, Parker R (2011) Stm1 modulates translation after 80S formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . RNA 17: 835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet NC, Schneider U, Helliwell SB, Stansfield I, Tuite MF, Hall MN (1996) TOR controls translation initiation and early G1 progression in yeast. Mol Biol Cell 7: 25–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglioni S, Benjamin D, Walchli M, Maier T, Hall MN (2022) mTOR substrate phosphorylation in growth control. Cell 185: 1814–1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T, Hall MN (1999) The TOR signalling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient‐regulated transcription factors. Nature 402: 689–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Shem A, Garreau de Loubresse N, Melnikov S, Jenner L, Yusupova G, Yusupov M (2011) The structure of the eukaryotic ribosome at 3.0 a resolution. Science 334: 1524–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Baird MR, Yip MC, Murray J, Shao S (2018) Structures of translationally inactive mammalian ribosomes. Elife 7: e40486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GA, Gomez TA, Deshaies RJ, Tansey WP (2010) Combined chemical and genetic approach to inhibit proteolysis by the proteasome. Yeast 27: 965–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer TC, Weaver CM, McAfee KJ, Jennings JL, Link AJ (2006) Systematic identification and functional screens of uncharacterized proteins associated with eukaryotic ribosomal complexes. Genes Dev 20: 1294–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandin V, Sikstrom K, Alain T, Morita M, McLaughlan S, Larsson O, Topisirovic I (2014) Polysome fractionation and analysis of mammalian translatomes on a genome‐wide scale. J Vis Exp 51455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N (2004) mTOR signaling to translation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 279: 169–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Hall MN (2017) Nutrient sensing and TOR signaling in yeast and mammals. EMBO J 36: 397–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, Yoshino K, Oshiro N, Hidayat S, Tokunaga C, Avruch J, Yonezawa K (2002) Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell 110: 177–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Nagai R, Abe T, Wada M, Ito K, Takeuchi‐Tomita N (2018) Tight interaction of eEF2 in the presence of Stm1 on ribosome. J Biochem 163: 177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner L, Melnikov S, Garreau de Loubresse N, Ben‐Shem A, Iskakova M, Urzhumtsev A, Meskauskas A, Dinman J, Yusupova G, Yusupov M (2012) Crystal structure of the 80S yeast ribosome. Curr Opin Struct Biol 22: 759–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskas E (1972) Serum‐mediated stimulation of protein synthesis in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. J Biol Chem 247: 5470–5476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, King JE, Latek RR, Erdjument‐Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM (2002) mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient‐sensitive complex that signals to the cell growth machinery. Cell 110: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Deplazes A, Sohrmann M, Peter M (2008) Mature ribosomes are selectively degraded upon starvation by an autophagy pathway requiring the Ubp3p/Bre5p ubiquitin protease. Nat Cell Biol 10: 602–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressler D, Hurt E, Bassler J (2010) Driving ribosome assembly. Biochim Biophys Acta 1803: 673–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson O, Morita M, Topisirovic I, Alain T, Blouin MJ, Pollak M, Sonenberg N (2012) Distinct perturbation of the translatome by the antidiabetic drug metformin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 8977–8982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Qian SB (2016) Characterizing inactive ribosomes in translational profiling. Translation (Austin) 4: e1138018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R, Jacinto E, Wullschleger S, Lorberg A, Crespo JL, Bonenfant D, Oppliger W, Jenoe P, Hall MN (2002) Two TOR complexes, only one of which is rapamycin sensitive, have distinct roles in cell growth control. Mol Cell 10: 457–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma XM, Blenis J (2009) Molecular mechanisms of mTOR‐mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C, Grummt I (2006) Ribosome biogenesis and cell growth: mTOR coordinates transcription by all three classes of nuclear RNA polymerases. Oncogene 25: 6384–6391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D, Shin S, Goullet de Rugy T, Samain R, Baer R, Strehaiano M, Masvidal‐Sanz L, Guillermet‐Guibert J, Jean C, Tsukumo Y et al (2019) eIF4A inhibition circumvents uncontrolled DNA replication mediated by 4 E‐BP1 loss in pancreatic cancer. JCI Insight 4: e121951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto A, Sugihara Y, Shibakawa M, Oshima K, Matsuda T, Nadano D (2018) The mRNA‐binding protein Serbp1 as an auxiliary protein associated with mammalian cytoplasmic ribosomes. Cell Biochem Funct 36: 312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisareva VP, Skabkin MA, Hellen CU, Pestova TV, Pisarev AV (2011) Dissociation by Pelota, Hbs1 and ABCE1 of mammalian vacant 80S ribosomes and stalled elongation complexes. EMBO J 30: 1804–1817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post H, Penning R, Fitzpatrick MA, Garrigues LB, Wu W, MacGillavry HD, Hoogenraad CC, Heck AJ, Altelaar AF (2017) Robust, sensitive, and automated Phosphopeptide enrichment optimized for low sample amounts applied to primary hippocampal neurons. J Proteome Res 16: 728–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossliner T, Skovbo Winther K, Sorensen MA, Gerdes K (2018) Ribosome hibernation. Annu Rev Genet 52: 321–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proud CG (2019) Phosphorylation and signal transduction pathways in translational control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 11: a033050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, Sabatini DM (2017) mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 169: 361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulard A, Cremonesi A, Moes S, Schutz F, Jeno P, Hall MN (2010) The rapamycin‐sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase a toward some but not all substrates. Mol Biol Cell 21: 3475–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Elzen AM, Schuller A, Green R, Seraphin B (2014) Dom34‐Hbs1 mediated dissociation of inactive 80S ribosomes promotes restart of translation after stress. EMBO J 33: 265–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke N, Baby J, Van Dyke MW (2006) Stm1p, a ribosome‐associated protein, is important for protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae under nutritional stress conditions. J Mol Biol 358: 1023–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke N, Chanchorn E, Van Dyke MW (2013) The Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Stm1p facilitates ribosome preservation during quiescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 430: 745–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Venrooij WJ, Henshaw EC, Hirsch CA (1972) Effects of deprival of glucose or individual amino acids on polyribosome distribution and rate of protein synthesis in cultured mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 259: 127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Liang C, Zheng M, Liu L, An Y, Xu H, Xiao S, Nie L (2020) Ribosome hibernation as a stress response of bacteria. Protein Pept Lett 27: 1082–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner JR (1999) The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends Biochem Sci 24: 437–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JN, Buschauer R, Mackens‐Kiani T, Best K, Kratzat H, Berninghausen O, Becker T, Gilbert W, Cheng J, Beckmann R (2020) Structure and function of yeast Lso2 and human CCDC124 bound to hibernating ribosomes. PLoS Biol 18: e3000780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]