Abstract

Objectives:

Falls are the most common cause of injury related deaths in people over 75 years. The aim of this study was to explore the experience of providers (instructors) and service users (clients) of a fall’s prevention exercise programme and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Derbyshire, UK.

Methods:

Ten one-to-one interviews with class instructors and five focus groups with clients (n=41). Transcripts were analysed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results:

Most clients were initially motivated to attend the programme to improve their physical health. All clients reported improvements in their physical health as a result of attending the classes; additional benefits to social cohesion were also widely discussed. Clients referred to the support provided by instructors during the pandemic (online classes and telephone calls) as a ‘life-line’. Clients and instructors thought more could be done to advertise the programme, especially linking in with community and healthcare services.

Conclusions:

The benefits of attending exercise classes went beyond the intended purpose of improving fitness and reducing the risk of falls, extending into improved mental and social wellbeing. During the pandemic the programme also prevented feelings of isolation. Participants felt more could be done to advertise the service and increase referrals from healthcare settings.

Keywords: COVID-19, Exercise, Falls Prevention, Frailty

Introduction

Older people are at increased risk of having a fall compared to younger adults, and falls are the most common cause of injury-related deaths amongst this group[1-3]. Common risk factors for falls among older people in the community include previous falls, fear of falling, balance problems, gait and mobility problems, pain, use of some medications, some cardiovascular conditions, cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, stroke and diabetes[4]. Multifactorial interventions are recommended for older people with recurrent falls or assessed as being at increased risk of falling[5]. Common components of these interventions include strength and balance training, home hazard assessment and intervention, vision assessment and referral and medication review[5]. Older people living in the community with a history of recurrent falls and/or balance and gait deficit are most likely to benefit from a strength and balance programme[5].

Derbyshire is a county in the East Midlands region of England with a population in the region of 800,000[6]. Since 2005 the charity Age UK Derby and Derbyshire (AUKDD) has been a primary provider of community falls prevention services in Derbyshire. The service, known as ‘Strictly No Falling’ (SNF), is a community-based exercise programme which aims to support people who have fallen or are at risk of falling to improve their strength, balance, and coordination. The service is available for residents of Derbyshire who are over the age of 50; however, it is also accessible to younger people who are at risk of falling. In April 2021 SNF had a caseload of approximately 130 community classes provided throughout the region, with approximately 2000 weekly attendees[7]. The structured exercise sessions are delivered from community venues across Derbyshire and include chair-based exercise (CBE), Otago, postural stability groups (PSG), Tai Chi and Qigong.

From 23rd March 2020, UK residents were asked to stay at home in the first SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic lockdown. SNF classes were amongst a multitude of services required to cancel all face-to-face activity. Where possible SNF moved to holding classes online or SNF instructors were encouraged to maintain contact (via phone, text messages) with their class members. As COVID-19 restrictions eased after the first lockdown, face-to-face classes were encouraged to re-commence in line with government guidelines. Towards the end of 2020 the UK went into its second COVID-19 lockdown, again preventing face-to-face SNF classes to be held in person until spring/summer of 2021.

Given the benefits of strength, balance and coordination training for people who are at risk of falling, understanding participants’ and providers’ experiences of this type of service, particularly barriers and facilitators to attending, will help to enhance existing services and inform the commissioning of future provision. The aim of this qualitative study was to explore, across a range of class types, the experience of providers (instructors) and service users (clients) of SNF to understand their motivations for initial and ongoing attendance. There are limited studies have evaluated falls prevention interventions during the COVID-19[8-10]. In addition, therefore, we aimed to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on attendance and provision of SNF. Our study brings new knowledge about the experience of a community-based falls prevention programme among people living in an economically diverse region of the East Midlands with a mix of urban and rural areas, both before and during the pandemic.

Methods

A qualitative study was carried out with two groups of participants: 1) those who organised and ran the SNF classes (referred to as ‘instructors’) were invited to complete a one-to-one interview and 2) service users who attended SNF classes (referred to as ‘clients’) were invited to partake in a focus group. Focus groups with already established SNF groups were used due to being well suited to the aims of the study (to explore experiences of the exercise programme and where possible reach consensus). In addition, these pre-existing groups made it easier for clients to relate to shared group experiences and outline any opposing views[11]. This paper follows the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines (Supplementary File 1).

Interview and focus group schedules

Separate schedules were developed for the instructor interviews and for the client focus groups by the project team before being reviewed by AUKDD to check how we referred to different aspects of the exercise programme were correct (e.g. we were advised the term ‘client’ was used for those who participated). Both schedules (for schedules, see Supplementary File 2). included open ended questions to explore motivations around initial and continued provision/attendance to classes, the experience of being involved in the programme, and any potential barriers to client attendance. In addition, all areas discussed also considered any impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were asked to complete a short set of demographic questions.

Participant recruitment and data collection

Researchers purposely sampled 25 SNF instructors (out of a possible 66 provided by AUKDD) to maximise the diversity of types of exercise classes, modes of delivery (online and face to face) and locations (to cover both urban and rural areas) throughout Derbyshire, inviting them via email to take part in a one-to-one interview. Potential participants were provided with an information sheet and asked if they had any questions before agreeing to take part. Interviews were arranged with ten instructors who expressed their interest in taking part in the study. All interviews were completed over an online platform (Zoom) with one researcher (SC) at a time convenient to the participants. On average interviews lasted 53 minutes (range, 31-70 minutes). In addition, interviewees were approached about the possibility of holding a focus group with clients from one of their SNF classes.

Focus groups were held with five SNF classes, led and facilitated by two researchers (SC & LJ) either face-to-face (n=3) or online (n=2). Class instructors did not attend any of the focus groups. Forty-one clients attended a focus group discussion in total (groups ranged from 5-15 participants) and lasted on average 45 minutes (range, 27-65 minutes). All participants provided verbal consent and were provided with a £10 shopping voucher to thank them for their time.

Data analysis

All interviews and focus groups were digitally audio-recorded, assigned a unique code, and then transcribed verbatim (by a university approved external transcription company or the university’s automated transcription service). Following receipt of the transcripts, they were checked prior to uploading and managing in NVivo (Version 12). Transcripts were analysed following the six stages of Braun and Clarke’s 2006 inductive thematic analysis, an approach that allows coding and theme development to be directed by the content of the data[12]. The initial stages of thematic analysis were followed separately for the transcripts derived from one-to-one interviews (instructors) and focus groups (clients). Firstly researchers (LJ and JM) familiarised themselves with the data, with LJ reading all and JM reading one third of the transcripts independently.

Initial themes and sub-themes were identified separately for the instructor and client data and the two researchers met to discuss these. As there were many similarities in the initial themes (and sub-themes) identified in the instructor and client transcripts researchers made the decision to combine and analyse both datasets together. The integration of both one to one interviews and focus groups has been shown to led to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of exploration via participant triangulation and a larger sample size[13].

Both researchers then carried out line-by-line coding on a sample of both interview and focus group transcripts before establishing a set of potential groupings of codes into themes. Researchers then met to discuss and agreed upon a set of themes and what they encompass, resulting in a coding manual across the integrated datasets. This consensus-based approach aimed to minimise as much as possible individual biases and enhance the credibility of the analysis[14]. One researcher (LJ) then coded the remaining transcripts using the agreed coding manual.

Results

Participants

Of the 10 instructors and 41 clients recruited, the majority were female (instructors n=9 (90%), clients n=34 (83%)) and White British (94%). Clients had been a member of their SNF class for an average of 3 years (range, 3 months to 7 years and 9 months), and instructors had been delivering classes for an average of 5 years and 9 months (range, 1 year and 5 months to 12 years). Participating instructors held on average four classes per week (range, 1-7) and many delivered a range of classes, to include Tai Chi, CBE, Otago, Qigong, PSG throughout both rural and urban locations within Derbyshire. All apart from three instructors delivered CBE with the majority of participating clients attended a CBE class or a mix of CBE and PSG or Otago.

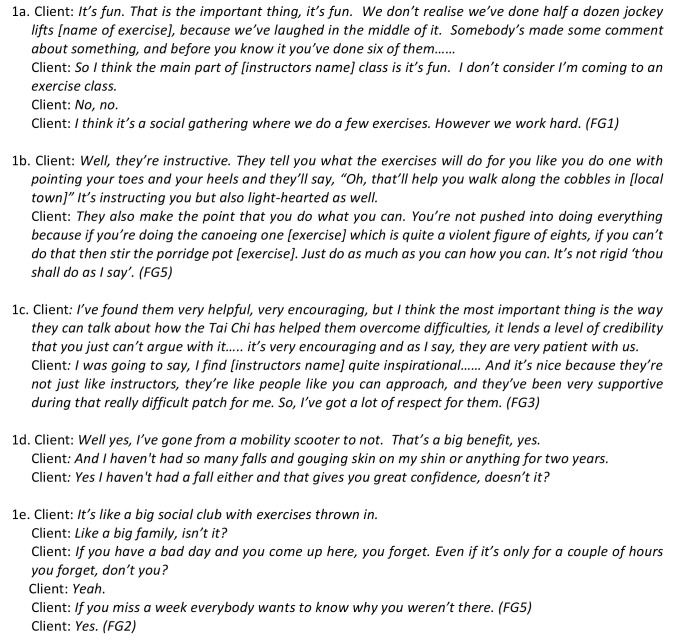

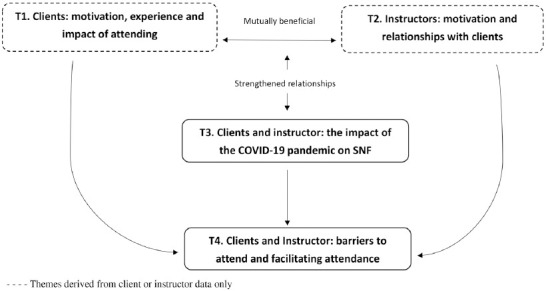

Four inter-related themes are presented below with selected excerpts from interviews and focus groups (Figures 1-4) alongside interview (I) or focus group (FG) ID numbers. One theme was drawn from data collected from clients only (Clients: motivation, experience, and impact of attending) and another from instructors only (Instructors: motivation and relationship with clients). The remaining two themes were obtained from information across the whole dataset. A thematic map demonstrating the relationships between themes is provided in Supplementary File 3.

Figure 1.

Clients: motivation, experience and impact of attending.

Figure 4.

Barriers to attend and facilitating attendance.

Theme 1. Clients: motivation, experience, and impact of attending (client only)

Opinions outlined in this theme are largely derived from reflections on in-person classes occurring outside of national COVID-19 restrictions.

Initial motivation to join: A small number of clients said they had been referred into SNF classes by a healthcare service/professional; however, the vast majority stated that they had heard about SNF classes through word of mouth and subsequently attended. For most, the primary driver to attend a SNF class was linked to improving their physical health, reasons included: to move more, support balance and movement, get stronger, ease pain, prevent falls, or because previous forms of exercise were no longer possible due to declining health or aliments. That said, there were a few clients who said they were primarily interested in attending to meet new people.

Experience of attending and the role of the instructor: All clients agreed that the classes were enjoyable and spoke about how much fun they had whilst attending; attributed to both fellow clients and instructors. Clients found the SNF sessions physically challenging however many said the fun and laughter experienced made the session easier to complete (Figure 1; 1a) and unlike other exercise classes they had previously attended. Clients thought the classes were well organised and a few said they enjoyed the changing content of the classes.

All clients spoke incredibly positively about instructors, describing them as approachable, clear, patient, and caring. Clients liked instructors ‘person-centred’ approach which fostered a non-judgmental and supportive atmosphere to exercise in. Clients thought instructors were attentive to their needs during the classes and if necessary tailored exercises to an individual’s ability (1b). Clients praised instructors for how they described and linked the benefits of the taught exercises to their everyday life (1b), and many spoke about the high level of knowledge and credibility instructors brought to their role (1c). Several clients considered their instructor a friend and a few gave examples of where an instructor had supported them through a particularly difficult time in their life (1c). Many of those doing CBE said their class was one of, if not the, highlight of their week (outside of the pandemic restrictions period) and added that the class gave them something to structure their week around; for a few, their SNF class was the only face-to-face contact they had throughout their week.

Impact of attending: Clients outlined only positive aspects of being involved in the SNF programme. Clients felt that by attending SNF sessions it had prevented potential falls (1d), and that instructors had taught them how to safely fall and get up after a fall. As suggested by their instructor, a few clients had incorporated taught exercises into their daily lives (e.g. completed whilst boiling the kettle or brushing their teeth). However, nearly all clients said the benefits of SNF went beyond simply ‘preventing falls’, in fact it had a positive influence on their physical, mental, and social wellbeing. Since attending SNF classes clients highlighted improvements in their strength, balance, coordination, flexibility, and in their day-to-day movement (e.g. lifting grandchildren or washing their hair) (1d). For many, these physical improvements (e.g. lack of falls or improved balance) had increased their overall confidence and in turn improved their mental health (1d). In addition, SNF sessions gave clients a ‘sense of purpose’ and facilitated group membership and friendships (1e). Clients spoke about the camaraderie amongst group members and how they were a support network for one another.

Motivation for continued attendance: Most notably these reasons included: the enjoyment and fun of the classes (1a), the nature of the instructors (1b, 1c), the evident physical and mental health improvements (1d), and the social aspects of being part of a supportive group (1e). Client views on the importance and benefits (physical, mental, and social) of the SNF programme intensified when face-to-face classes ceased during the periods of heightened COVID-19 restrictions (Theme 3).

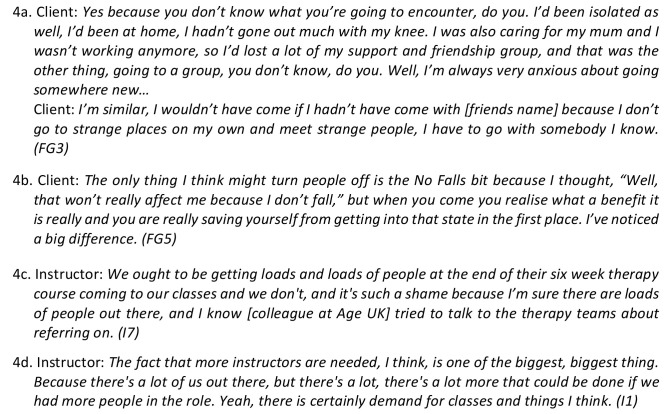

Theme 2: Instructors: motivation and relationships with clients (instructor only)

Initial and continued motivation: Instructors were motivated in their role by the idea of supporting older people to keep active, acknowledging the benefits this could bring to those in later life. In addition, a couple of instructors mentioned how they were drawn to the role as they really enjoyed working with an older population (Figure 2; 2a). Helping older people keep healthy (both physically and mentally) and witnessing clients improve as a result of the SNF programme is what motivated all instructors to continue in their role (2a). Several instructors outlined how teaching the SNF classes was also beneficial for them; keeping them socially active and supporting their mental and physical health. A few also mentioned the income received from running SNF classes however this was not what ultimately motivated them to continue in the role (2a).

Figure 2.

Instructors: motivation and relationships with clients.

Enjoyment in their role and relationship with clients: All instructors spoke about how much they enjoyed or ‘loved’ their role as an instructor, many linked this enjoyment to the clients they came into contact with (2b). Instructors echoed comments by clients relating to the fun and enjoyment they had during the SNF classes (Theme 1), many referred to the ‘laughs’ or ‘banter’ they all had during the classes (2b). Instructors cared about, respected, and valued client relationships (2b), a couple of instructors mentioned socialising with clients outside of the SNF classes. Although most instructors could not think of anything they disliked about their role, a few mentioned not enjoying the data recording/entry they were required to do for AUKDD which was attributed to their lack of confidence with IT. That said, these instructors outlined how AUKDD were always available to support with these tasks.

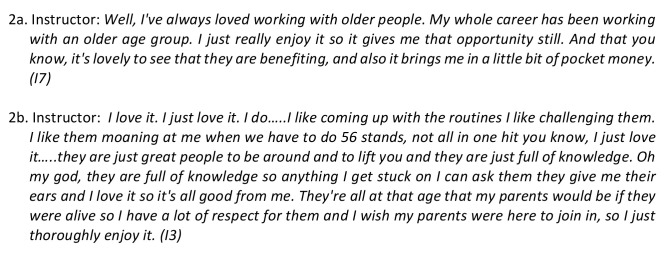

Theme 3. Client and instructors: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SNF

Immediate impact of the pandemic on SNF classes: Most classes moved online (via Zoom) during periods of heightened COVID-19 government restrictions however several clients said they had been unable to access these because they did not have or could not use the technology required. In instances where clients were unable to join online classes or their class did not move online, instructors outlined how they attempted to keep in regular weekly contact with their class members over the telephone. In addition, instructors said they created ‘WhatsApp’ groups for each of their SNF classes which enabled dialogue between instructors and fellow clients and a few instructors also spoke about visiting clients at homes (in line with government guidelines) so they could ‘check-in’ with them and distribute items such as exercise games, a SNF DVD, face masks, resistance bands, exercise monitoring forms and wellbeing leaflets.

Instructors and clients said the success of the online classes varied and that some initially struggled to get to grips with classes that were delivered virtually. Clients said they sometimes struggled to see and follow instructors on their small screens and instructors felt it was difficult on occasions to supervise the whole group online and support individual clients with the exercises (Figure 3; 3a). A couple of instructors did have concerns over safety whilst clients completed exercises at home during their Zoom classes (3a). A few instructors also commented upon how they themselves were also navigating a global pandemic and that the regular telephone calls with clients sometimes became difficult to complete as they were time consuming and often emotionally draining (3b). Instructors were thankful for the amount of support AUKDD offered during this time in setting up online classes, providing items for clients (e.g. resistance bands and masks), providing financial support to maintain telephone contact with participants, support in completing client telephone calls and offering emotional support during this difficult time.

Figure 3.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on SNF.

Although there were some difficulties with having classes online and telephoning clients, everyone spoke about how all of these forms of communication during periods of lockdown were a ‘life-line’ or a ‘saviour’ as clients described feeling very isolated during this time (3c & 3d). Clients said they structured their whole week around their SNF contact and they truly appreciated how instructors went out of their way to support and care for them during periods of heightened COVID-19 restrictions (3d). As a result, many said that they felt the function of SNF shifted from a physical to a mental health focus during periods of COVID-19 lockdown.

Returning to in-person SNF classes: As COVID-19 restrictions eased instructors said they informed clients when they would be re-starting in person sessions and of any COVID -19 restrictions that would be in place (e.g. face visors, social distancing). Clients felt reassured by this and praised instructors for creating a ‘COVID-safe’ environment for them to return to. Once COVID-19 restrictions allowed, instructors said most of their clients returned to in-person classes. A few classes did remain online; these classes tended to be those newly established during the pandemic.

There was a consensus amongst instructors that the few clients who did not return were those who did not participate in Zoom classes (if available) or weekly telephone calls. As a result, instructors felt that maintaining contact via these channels was imperative to retaining people in the SNF programme during the pandemic. Additional barriers for returning to in-person classes highlighted by clients and instructors included concern over catching COVID-19 and an overall loss of confidence (e.g. in leaving the house or driving to the SNF venues). Instructors said they also felt this loss in confidence was because of the decline in both physical and mental health of clients, something they had observed in their clients on return to in-person classes (3e). A few clients also felt both their physical and mental wellbeing had been negatively impacted because of the not attending in-person SNF classes.

The longer-term impact of the pandemic: Most clients outlined how they preferred in-person to online SNF classes. As outlined earlier (Theme 1) clients thoroughly enjoyed in-person classes and gained a lot from these; physically, mentally, and socially. However, a few clients from one focus groups said they preferred online classes because they did not have to contend with weather conditions and because they received more focused attention from the instructor. Instructors felt there was still a place for online SNF classes even once all COVID-19 restrictions have been removed. Specifically, they felt it was beneficial that online groups allowed them to cover larger geographical areas of the county which also enabled SNF classes to be based on client ability and not area. A couple of instructors said they did not like the idea of online SNF classes for new clients as they would not be able to fully assess newcomers’ fragility or support them physically in completing the exercises.

Instructors and clients said the COVID-19 pandemic had reaffirmed the importance of human relationships, as previous outlined, some clients felt the contact made through their SNF class had been a ‘life-saver’ during the height of the pandemic. Both instructors and clients said they felt the communication they had had with one another throughout the pandemic had brought them all closer together (3f). For many, communication via ‘WhatsApp’ groups and instructor-client text messaging had continued since returning to in-person classes. Clients enjoyed this continued contact outside of the SNF session and felt this was something positive to have come out of the pandemic. A few instructors had also noticed since returning to in-person classes that many clients spent longer talking at the start or end of a session and/or they had started socialising outside of the exercise session (3f).

Instructors and clients were pleasantly surprised and welcomed the fact that they had become more IT literate and had learnt how to use Zoom because of the pandemic, a few clients went on to add how isolated they would have been without it.

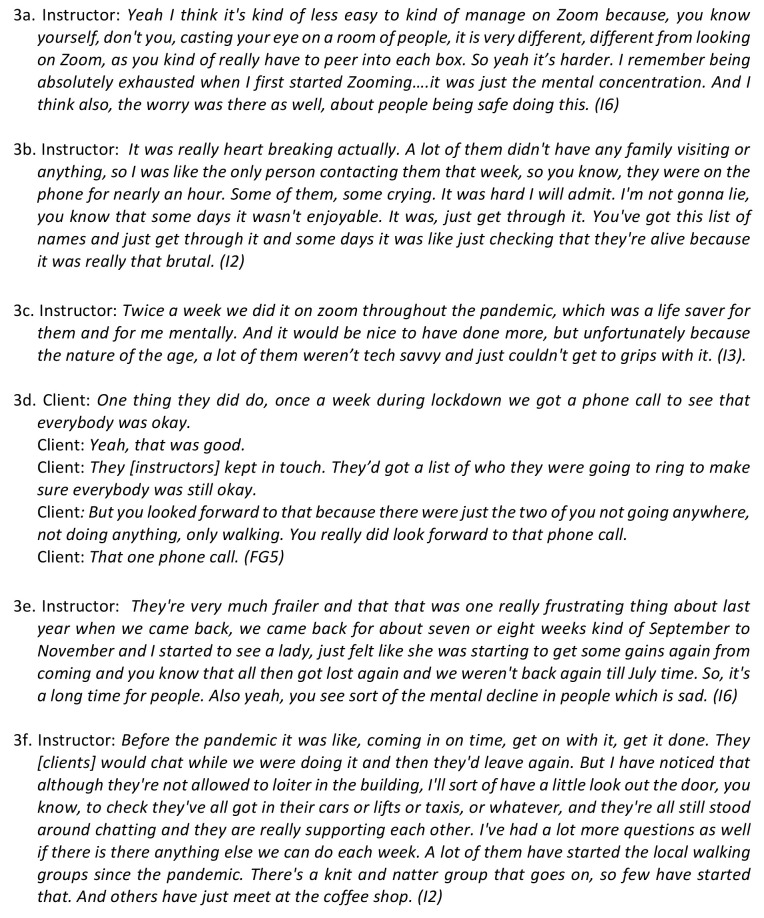

Theme 4. Client and instructors: barriers to attend and facilitating attendance

Barriers to attend a SNF class: Several clients spoke about how nervous they had been prior to arriving at their first SNF class and they felt this was one of the main barriers to attend a SNF class (Figure 4; 4a). Several instructors said they also thought a lack of confidence (especially in physical ability) or fear around what might be encountered prevented potential clients from attending a SNF class. As a result, instructors said they often tried to talk to a new client on the telephone prior to attending and would ask them to arrive earlier to their first class to ensure they felt welcomed and cared for. Several instructors and clients said a lack of transport would prevent people from attending a SNF class, especially for those living in more rural areas. A few clients said they would not be able to attend if they were not driven by a friend, relative or fellow client; a couple also mentioned how voluntary agencies organising free transport for clients had ceased since the start of the pandemic. Although the vast majority of clients said they felt the costs of a SNF class was extremely reasonable and did not think it would deter people from joining, they thought any additional transport costs (e.g. for those requiring taxis or fuel costs) could prevent people from attending. A few instructors and clients said they had noticed a decline in class attendance when the weather was poor (e.g. cold or icy) or when nights draw in over the winter months, especially for those with poorer mobility.

Several clients thought the word ‘falls’ in the programmes name might prevent people from attending as older people might not consider falling to be something that might happen to them. In addition, as previously outlined (Theme 1), clients felt the programme went far beyond simply preventing falling (4b). One focus group suggested the name of the programme had changed recently to ‘stronger for longer’ which they preferred. Tai Chi instructors and clients said they also thought a lack of understanding about this discipline or its association with martial arts or religion might put people off attending that type of exercise class.

Facilitating future attendance to SNF classes: Although instructors and clients acknowledged SNF classes were currently advertised via the AUKDD website and through posters in local settings, there was a perception that not many of the target demographic knew about the programme. As a result, instructors and clients felt more targeted promotion could, ideas included: a national TV campaign, posters in supermarkets, adverts in free local magazines and on Facebook, and utilising links to community and healthcare settings. A couple of instructors and clients felt the SNF advert and logo could be improved by making them more eye catching, attractive and modern. Again, instructors acknowledged that AUKDD had worked hard to try and work with healthcare providers (GP surgeries, hospitals, physiotherapy teams) to increase referrals into SNF however they still felt these referral rates were well below what they would have expected from these services (4c). A few instructors mentioned how their current classes were full and they were unable to take on any new clients and therefore suggested training more instructors (4d).

Discussion

Key findings

Many clients initially attended SNF due to a desire to improve their physical health and to meet people; most subsequently found that the programme had broader benefits than improving physical health and preventing falls, including improving their mental wellbeing and the opportunity to socialise. Both clients and instructors spoke about the enjoyment they got from SNF classes. Clients praised instructors for their ‘person-centred’ approach and felt they went ‘above and beyond’ to support them during the pandemic.

The importance of SNF, beyond its role as an exercise programme, was amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most clients preferred face-to-face to online classes; however, online classes and additional communication helped to prevent isolation during lockdowns. A small number of clients preferred online classes and instructors felt that continued availability of online classes would increase accessibility. Perceived barriers to attending SNF included nervousness around attending the first session, lack of and the cost of transport, poor weather conditions and the word ‘falls’ in the programme name. Word of mouth brought most new clients to the programme therefore clients and instructors thought more could be done to advertise the programme. There was no difference in the themes identified from the less densely populated dispersed areas.

Comparison with existing studies

A key finding from our study is that most participants were extremely positive about SNF and emphasised that the benefits of attending SNF classes went well beyond the intended purpose of improving physical fitness and reducing the risk of falls. Previous studies have identified health and social interaction[15] and a desire to maintain independence[16,17] as key motivators for engaging with falls prevention. Our findings echo those from existing studies which show that many older people do not identify themselves as being at risk of falling[15,17] and that services advertised as aiming to reduce falls may not be regarded as personally relevant or appropriate for them[18]. Overall, our finding that clients perceived there to be a wide range of benefits from attending SNF classes supports the view that it may be more helpful to embed falls prevention within a wider context of wellbeing and independence[19].

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a strength and balance service for older adults; our findings show how the pandemic highlighted the importance these sorts of programmes for mental health and reducing isolation as well as the physical benefits. Instructors were able to mitigate the effects of the pandemic on the service by providing online classes and additional support, e.g. via telephone. The COVID-19 pandemic required a transition to online delivery for many services, and patients and health care providers have been found to have high levels of satisfaction with telehealth during the pandemic[20]. In our study face-to-face delivery was usually preferred by clients, which is perhaps unsurprising given that the service involves a non-clinical group activity where social interaction contributes to the perceived benefits. However, our findings suggest that there is an ongoing role for online delivery; it can minimise barriers to access and for some clients may be perceived to improve the experience.

Strengths and limitations

Our study gave an insight into perceptions of the service as it is normally run, but also provided insights in the effects of the pandemic on the service which may have implications for its future delivery. Our study participants included both clients and instructors, which allowed us to explore the views of two key groups of stakeholders. We used a rigorous approach to our analysis including a consensus-based approach to coding of the interview and focus group data.

Our study looked at a single service in only one county in England. Most of our participants were female and there may be some selection bias in our sample. However, the higher proportion of females reflects the make-up of the participants in SNF (routine data shared by AUKDD). There is some existing evidence that men identify women as a priority group for balance and fall prevention exercise and that women regard themselves as being more receptive to fall prevention messages than men; there may be a need to promote the service differently to males and females to maximise uptake[21].

Implications

Community-based strength and balance exercise programmes are recognised as effective in increasing physical activity and reducing falls; however, participants must perceive ongoing benefits for participation and benefits to be sustained[22]. Our study has revealed that perceptions of SNF are overwhelmingly positive, and that the benefits are perceived to go beyond purely physical benefits; strength and balance classes may be a major contributor to clients’ overall health and wellbeing. Certain barriers and concerns should be addressed to help maximise participation in the service. This includes reducing barriers to transport and continuing to offer online classes for individuals who prefer this option. Few participants had been referred by a health care professional; increasing awareness of the service and its benefits among health care professionals may increase participant uptake. Changing the name of the service to avoid the word ‘falls’ may make the service more appealing to older adults who do not see themselves as being at risk of falling and to emphasise the wider benefits of the classes. Ensuring that adequate support and encouragement is provided prior to attending may reduce apprehensiveness and increase participation.

Conclusions

Most clients were initially motivated to attend the programme to improve their physical health. SNF is perceived by both clients and instructors to contribute to both physical and wellbeing among older adults; its benefits are seen to extend beyond falls prevention alone. During the COVID-19 pandemic, continued delivery of the SNF classes as well as additional support outside of classes helped to prevent feelings of isolation. While most clients prefer face-to-face classes, some continued delivery of online classes may help to overcome barriers to access. Participants said that raising awareness of the programme amongst healthcare professional could increase referrals into the service. In addition, further support for client transport could facilitate attendance.

Ethical approval

This project was approved by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (University of Nottingham, UK) Research Ethics Committee in November 2021 (FMHS-405-1121).

Funding

This study was supported by Age UK Derby and Derbyshire, England.

Authors’ contributions

JM, TL, LJ, & IB developed the study, with SC & LJ completing data collection. LJ & JM conducted independent analysis of the transcripts and LJ coded all the data. LJ & TL led the draft of the manuscript. All authors had input to the final version of the manuscript.

Participant consent

Verbal consent was taken prior to data collection; in line with ethical guidance outlined from the Faculty of Medicine.

Supplementary Files

File 1.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)*.

| Page/line no(s). | |

|---|---|

| Title and abstract | |

| Title - Concise description of the nature and topic of the study Identifying the study as qualitative or indicating the approach (e.g., ethnography, grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g., interview, focus group) is recommended | P9 |

| Abstract - Summary of key elements of the study using the abstract format of the intended publication; typically includes background, purpose, methods, results, and conclusions | P9 |

| Introduction | |

| Problem formulation - Description and significance of the problem/phenomenon studied; review of relevant theory and empirical work; problem statement | P9-10 |

| Purpose or research question - Purpose of the study and specific objectives or questions | P10 |

| Methods | |

| Qualitative approach and research paradigm - Qualitative approach (e.g., ethnography, grounded theory, case study, phenomenology, narrative research) and guiding theory if appropriate; identifying the research paradigm (e.g., post positivist, constructivist/ interpretivist) is also recommended; rationale** | P10 |

| Researcher characteristics and reflexivity - Researchers’ characteristics that may influence the research, including personal attributes, qualifications/experience, relationship with participants, assumptions, and/or presuppositions; potential or actual interaction between researchers’ characteristics and the research questions, approach, methods, results, and/or transferability | P10-11 |

| Context - Setting/site and salient contextual factors; rationale** | P10 |

| Sampling strategy - How and why research participants, documents, or events were selected; criteria for deciding when no further sampling was necessary (e.g., sampling saturation); rationale** | P10-11 |

| Ethical issues pertaining to human subjects - Documentation of approval by an appropriate ethics review board and participant consent, or explanation for lack thereof; other confidentiality and data security issues | P17 |

| Data collection methods - Types of data collected; details of data collection procedures including (as appropriate) start and stop dates of data collection and analysis, iterative process, triangulation of sources/methods, and modification of procedures in response to evolving study findings; rationale** | P10 |

| Data collection instruments and technologies - Description of instruments (e.g., interview guides, questionnaires) and devices (e.g., audio recorders) used for data collection; if/how the instrument(s) changed over the course of the study | P10-11 |

| Units of study - Number and relevant characteristics of participants, documents, or events included in the study; level of participation (could be reported in results) | P11 |

| Data processing - Methods for processing data prior to and during analysis, including transcription, data entry, data management and security, verification of data integrity, data coding, and anonymization/de-identification of excerpts | P10-11 |

| Data analysis - Process by which inferences, themes, etc., were identified and developed, including the researchers involved in data analysis; usually references a specific paradigm or approach; rationale** | P10-11 |

| Techniques to enhance trustworthiness - Techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis (e.g., member checking, audit trail, triangulation); rationale** | P10-11 |

| Results/findings | |

| Synthesis and interpretation - Main findings (e.g., interpretations, inferences, and themes); might include development of a theory or model, or integration with prior research or theory | P11-16 |

| Links to empirical data - Evidence (e.g., quotes, field notes, text excerpts, photographs) to substantiate analytic findings | P11-16 plus Figures 1-4 |

| Discussion | |

| Integration with prior work, implications, transferability, and contribution(s) to the field - Short summary of main findings; explanation of how findings and conclusions connect to, support, elaborate on, or challenge conclusions of earlier scholarship; discussion of scope of application/generalizability; identification of unique contribution(s) to scholarship in a discipline or field | P16-17 |

| Limitations - Trustworthiness and limitations of findings | P17 |

| Other | |

| Conflicts of interest - Potential sources of influence or perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions; how these were managed | P9 & online submission |

| Funding - Sources of funding and other support; role of funders in data collection, interpretation, and reporting | P17 & online submission |

The authors created the SRQR by searching the literature to identify guidelines, reporting standards, and critical appraisal criteria for qualitative research; reviewing the reference lists of retrieved sources; and contacting experts to gain feedback. The SRQR aims to improve the transparency of all aspects of qualitative research by providing clear standards for reporting qualitative research.

The rationale should briefly discuss the justification for choosing that theory, approach, method, or technique rather than other options available, the assumptions and limitations implicit in those choices, and how those choices influence study conclusions and transferability. As appropriate, the rationale for several items might be discussed together.

File 2.

Interview/focus group schedules.

| A. Instructor interview guide |

|---|

| Introduction |

| • Thank you for agreeing to take part in the evaluation. |

| • Review the purpose of the study in general: |

|

- Interested in hearing about why they got involved in SNF and their experience of being involved, especially interested in hearing about the impact of the pandemic. |

| - Make participant aware we are also holding focus groups with ‘clients’ as part of the evaluation. |

| • Statement on confidentiality, right to withdraw consent, recording of the telephone interview. |

| • Ask if the participant have any questions before starting the interview and that they are still happy to continue. |

| Background |

| 1. Could you tell me about how you first heard about the Strictly No Falls programme? |

| 2. How did you then get involved and become an instructor in Strictly No Falls? |

| - what was your understanding of the programme/what did you think the job would entail? |

| - Why did you initially decide to become an instructor – what motivated you? |

| - How long have you been employed/when did you qualify as an instructor? |

| Nature of the role |

| 3. Can you tell me about your job role as a SNF instructor, what it involves? (might want to talk about what it involved pre-pandemic first, then any changes since the pandemic/ongoing adjustments) |

| - Which and how many classes do you run? (type of class – eg. CBE, online or in person) |

| - Where are the classes (rural v. urban) |

| - How many clients do you have contact with on a weekly basis? - |

| How has this changed since the pandemic – face to face or online, any additional activities as a result of the pandemic? (pre pandemic, first lockdown announcement in March 2020, subsequent lockdowns until summer 2021, after restrictions were lifted) |

| 4. Can you tell me about the interaction you have with ‘clients’? |

| - How often do you contact/see them – during and outside of exercise classes - |

| Has the amount of contact changed during the pandemic (pre-pandemic, first lockdown announcement in March 2020, subsequent lockdowns until summer 2021, after restrictions were lifted |

| 5. What involvement/interactions do you have with those who support you/Age UK? |

| - How often do you contact/see them – during and outside of exercise classes - |

| Has the amount of contact changed during the pandemic (pre-pandemic, first lockdown announcement in March 2020, subsequent lockdowns until summer 2021, after restrictions were lifted) - What support have you received from Age UK? |

| Motivations behind/Benefits of SNF |

| 6. Why do you think people attend SNF? |

| - What motivates them to attend |

| - What are the benefits of the programme for them - Physical/psychological/social |

| 7. What motivates you to continue to work as an instructor on SNF? |

| - What do you enjoy most about your role |

| - What do you enjoy the least about your role |

| Potential barriers/changes to the programme |

| 8. Do you know of any barriers to attend SNF for older people? |

| - Know of any reasons why clients might not complete the initial 12 week programme |

| - Differences in types of exercise groups/urban v rural - |

| Impact of the pandemic (first lockdown announcement in March 2020, subsequent lockdowns until summer 2021, after restrictions were lifted) |

| 9. How could SNF be advertised/promoted to others? |

| - Continue as it is/any ideas? |

| 10. What do you think the programme does well and should continue to do? |

| - As a result of the pandemic did anything change that you thing should stay as it is? |

| 11. Going forward, are there any areas where you feel SNF could be changed/improved upon? |

| Either to - benefit/facilitate the client |

| - benefit/facilitate the instructor |

| 12. Is there anything related to SNF that we have not spoken about but feel is important to mention before we finish? |

| Closing remarks |

| • Do you have any questions for me before we end the interview? |

| • Check demographic questions answered • Thank you for your time • Arrangement of inconvenience allowance/retail voucher? |

| B. Client focus group guide |

| Introduction |

| • Thank you for agreeing to take part in the evaluation. |

| • Review the purpose of the study in general: - |

| Interested in hearing about why they got involved in SNF and their experience of being involved, especially interested in hearing about the impact of the pandemic. - |

| Make participants aware we are also conducting one to one interview with instructors as part of the evaluation. |

| • Statement on confidentiality, right to withdraw consent, recording of the focus group |

| • Ask if the participants have any questions before starting the interview and that they are still happy to continue. |

| • Reminder of some house rules of focus groups – please do not speak over each other, everyone’s views are important even if they are not the same as yours, please keep anything mentioned in the session between ourselves….doubt these will be too ferocious! |

| Background |

| 1. How did people first hear about SNF and how did they get involved? |

| - From who? |

| - If referred – how was this process? |

| 2. Prior to coming along to one of the sessions what did you think taking part in the SNF programme entailed? |

| - Types of exercise |

| - How and where it took place |

| - How did you feel prior to going along to your first session |

| 3. Initially, based on what you knew at the start, what motivated people to attend? |

| Being involved in the SNF programme |

| 4. Tell me about what being involved with SNF entails? |

| (might want to talk about what it involved pre-pandemic first, then any changes since the pandemic/ongoing adjustments) |

| - How many sessions on average do clients attend per week/month |

| - Which sessions do clients attend |

| - Online v. face 2 face sessions |

| - How has this changed since the pandemic |

| 5. Can you tell me about the relationship clients have with instructors? |

| - How often do you communicate – just in classes? |

| - What are the instructors like – friendly/helpful/supportive |

| - What impact did the pandemic have? |

| Motivations behind/Benefits of SNF |

| 6. Have people seen any benefits to attending SNF classes? |

| - Health/physical/psychological/social |

| - Impact of the pandemic |

| 7. Has attending/being part of SNF had any knock on effect/impact to other parts of your life? |

| 8. What motivates people to continue to attend SNF classes? |

| - Has this changed at all due to the pandemic? |

| Potential barriers/changes to the programme |

| 9. Do people know of any barriers other might have when considering whether to attend SNF? |

| - Know of any reasons why people might not complete the initial 12 week programme/drop out |

| - Differences in types of exercise groups/urban v rural |

| - Financial barriers |

| - Impact of the pandemic |

| 10. How could SNF be advertised/promoted to potential clients? |

| - Continue as it is/any ideas? |

| 11. What do you think the programme does well at and should continue to do? |

| - As a result of the pandemic did anything change that you thing should stay as it is? |

| 12. Going forward, Are there any areas where you feel SNF could be changed/improved upon? |

| Either to -benefit/facilitate the client |

| -benefit/facilitate the instructor |

| 13. Is there anything related to SNF that we have not spoken about but feel is important to mention before we finish? |

| Closing remarks |

| • Do you have any questions for me before we end the interview? |

| • Check demographic questions answered |

| • Thank you for your time |

| • Arrangement of inconvenience allowance/retail voucher? |

File 3.

Thematic Map of themes

Footnotes

Edited by: Dawn Skelton

References

- 1.Campbell AJ, Reinken J, Allan BC, Martinez GS. Falls in old age:a study of frequency and related clinical factors. Age and ageing. 1981;10(4):264–70. doi: 10.1093/ageing/10.4.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masud T, Morris RO. Epidemiology of falls. Age and ageing. 2001;30(Suppl 4):3–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.suppl_4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Williams CS. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(18):1279–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vieira ER, Palmer RC, Chaves PH. Prevention of falls in older people living in the community. BMJ. 2016;353:i1419. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Falls in older people:assessing risk and prevention [CG161] [Accessed 05/05/22]. Availabe from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg161/chapter/recommendations#older-people-living-in-the-community . 12 June 2013. [PubMed]

- 6.Office for National Statistics. Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK. [Accessed 05/05/22 June 2020]. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland .

- 7.Age UK Derby &Derbyshire. Strictly No Falling March 2020 –April 2021. Covid-19 Pandemic Response Report [personal communication] 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosco A, McGarrigle L, Skelton DA, Laventure RME, Townley B, Todd C. Make Movement Your Mission:Evaluation of an online digital health initiative to increase physical activity in older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital health. 2022;8:20552076221084468. doi: 10.1177/20552076221084468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dejvajara D AR, Palee P, Piankusol C, Sirikul W, Siviroj P. Effects of Home-Based Nine-Square Step Exercises for Fall Prevention in Thai Community-Dwelling Older Adults during a COVID-19 Lockdown:A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. IJERPH. 2022;19:10514. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiyoshi-Teo H, Izumi SS, Stoyles S, McMahon SK. Older Adults'Biobehavioral Fall Risks Were Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic:Lessons Learned for Future Fall Prevention Research to Incorporate Multilevel Perspectives. Innovation in aging. 2022;6(6):igac033. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igac033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitzinger J. The methodology of Focus Groups:the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health &Illness. 1994;16(1):103–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62(2):228–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathison S. Why Triangulate? Educational Researcher. 1988;17(2):13–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finnegan S, Bruce J, Seers K. What enables older people to continue with their falls prevention exercises?A qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e026074. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson L, Newton J, Jones D, Dawson P. Self-management and adherence with exercise-based falls prevention programmes:a qualitative study to explore the views and experiences of older people and physiotherapists. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2014;36(5):379–86. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.797507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardiner S, Glogowska M, Stoaddart C, Pendlebury S, Lasserson D, Jackson D. Older people's experiences of falling and perceived risk of falls in the community:A narrative synthesis of qualitative research. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2017;12(4):e12151. doi: 10.1111/opn.12151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Francis K, Todd C. Older people's views of advice about falls prevention:a qualitative study. Health Education Research. 2006;21(4):508–17. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballinger C, Clemson L. Older People's Views about Community Falls Prevention:an Australian Perspective. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2006;69(6):263–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews E, Berghofer K, Long J, Prescott A, Caboral-Stevens M. Satisfaction with the use of telehealth during COVID-19:An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2020.100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandlund M, Skelton D, Pohl P, Ahlgren C, Melander-Wikman A, Lundin-Olsson L. Gender perspectives on views and preferences of older people on exercise to prevent falls:a systematic mixed studies review. BMC Geriatrics. 2017;17(58) doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0451-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iliffe S, Kendrick D, Morris R, Griffin M, Haworth D, Carpenter H, et al. Promoting physical activity in older people in general practice:ProAct65+cluster randomised controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice. 2015;65(640):e731–e8. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X687361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]