Abstract

Purpose:

This work presents a case of secondary maculopathy associated with the use of erdafitinib (Balversa) for the management of bladder urothelial carcinoma with bony metastasis.

Methods:

A case report is presented.

Results:

A 58-year-old Hispanic man presented with blurry vision 3 weeks after starting erdafitinib for the management of bony metastases associated with urothelial carcinoma. A comprehensive evaluation identified multiple areas of subretinal fluid induced by erdafitinib. Throughout treatment, the ocular condition progressed, causing worsening of vision; this led to discontinuation of the drug. Discontinuation was associated with visual and anatomic function improvement.

Conclusions:

Fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) plays a major role in maintaining mature and premature retinal pigment epithelium cells. Drugs that inhibit the FGFR pathway block the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, leading to synthesis of antiapoptotic proteins. Erdafitinib is associated with ocular toxicity and leads to multifocal pigment epithelial detachments associated with secondary subretinal fluid.

Keywords: erdafitinib, FGFR, MAPK, central serous chorioretinopathy, RPE detachment, targeted therapy, mitogen-activated protein kinase retinopathy

Introduction

In recent years, advancements in cancer treatment have spurred the development of many targeted therapeutics that inhibit specific mutations to destroy tumor cells but not healthy cells, leading to a smaller toxicity profile and fewer side effects. These personalized treatment options have led to better overall patient survival and quality of life.

Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) are a type of receptor tyrosine kinase–signaling pathway expressed on the cell membrane that help facilitate proliferation, angiogenesis, and tissue homeostasis of human cells. 1 FGFR inhibitor treatment is a targeted therapy that is very effective in treating a variety of cancers; 7.1% of all cancer types have a molecular aberration involving the FGFR pathway. 2 Although such inhibitors are considered relatively safe, the side effects should be taken into consideration.

We present a case of erdafitinib-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor–associated retinopathy (MEKAR), onychauxis, and ageusia. This report highlights some ocular and systemic side effects of FGFR inhibitors that will likely be seen as the use of drugs targeting this pathway increases.

Methods

Case Report

A 58-year-old Hispanic man presented reporting blurry vision 3 weeks after starting erdafitinib (Balversa). He had a history of type 1 diabetes and bladder urothelial carcinoma that had been treated with a transurethral resection 3 years previously and with systemic chemotherapy in addition to pelvic radiation therapy for metastasis 1 year previously. He was then started on erdafitinib 8 mg/day after genetic testing confirmed an alteration in the FGFR gene.

Four weeks after the patient began taking erdafitinib, an ophthalmologic examination showed a best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/50 OD and 20/40 OS. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 18 mm Hg in both eyes. The pupils were round and reactive to light and accommodation. Full motility and a full confrontational visual field were noted. An anterior segment examination showed dry eyes with a breakup time of less than 5 seconds and a 1+ nuclear cataract. The rest of the anterior segment was normal.

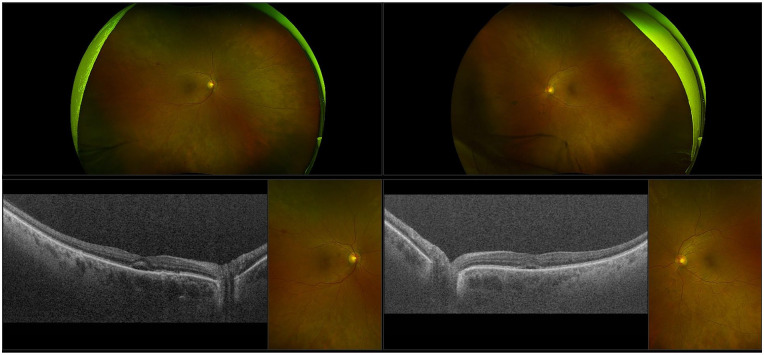

A dilated fundus examination showed an oval serous detachment in the macula in both eyes and in different areas in the retina as well as areas of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) mottling (Figure 1, A and B). Optical coherence tomography showed an RPE detachment and multifocal subretinal fluid (Figure 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

Ultra-widefield fundus photography of (A) the right eye and (B) the left eye shows macular oval serous detachment and scattered areas of retinal pigment epithelium mottling in the midperiphery. Optical coherence tomography of (C) the right eye and (D) the left eye shows macular subretinal fluid in both eyes and pigment epithelium detachment in the right eye.

The patient was started on dorzolamide drops in both eyes to lower the IOP and to improve the bilateral subretinal fluid. He also started artificial tears to manage his dry eyes. In addition to the ocular side effects, a general examination showed onychauxis (Figure 2) and ageusia.

Figure 2.

The patient’s fingernails thickened and grew outward because of erdafitinib-induced onychauxis.

Results

Four weeks after treatment with dorzolamide and artificial tears, the patient’s IOP pressure had decreased to 10 mm Hg; however, his vision remained stable.

The patient’s onychauxis continued to worsen, prompting the need for his nails to be wrapped in finger cots. Because of the ageusia, the patient could taste only some fruits, such as apples and bananas, as well as tomato sauce; however, the taste was altered. He was not able to taste salt. This resulted in a weight loss of 23 pounds over the 5 weeks after he began erdafitinib treatment. However, the erdafitinib treatment was successful in treating his tumors and the patient was able to stop the use of narcotics for pain management.

Four months after therapy, the patient developed an infection resulting from his neobladder, which prompted withholding the erdafitinib. A decision was made to permanently discontinue the use of the drug, taking into consideration the patient’s most recent BCVA and significant weight loss. Three weeks after stopping therapy, the patient came to our clinic for a monthly ophthalmologic follow-up. Although there was an improvement in the MEKAR bilaterally, the BCVA was 20/200 OU (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(A and B) Ultra-widefield fundus photography and (C and D) optical coherence tomography show improvement in both eyes after erdafitinib was withheld for 3 weeks.

Conclusions

Balversa (erdafitinib) is the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved targeted therapy for FGFR2-mutated and FGFR3-mutated urothelial carcinoma. Erdafitinib is used because of its antitumor activity in cancer cells with a known FGFR mutation. Its current FDA approval allows the use of the drug for bladder cancer that has progressed during or after at least 1 previous platinum-coating chemotherapy within the past 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-containing chemotherapy. 3

In BLC2001 clinical trial NCT02365597, erdafitinib had a 40% response rate; traditional chemotherapies had a response rate of only 10%. 4 With the success of erdafitinib in clinical trials, the FDA accelerated its approval for the treatment of FGFR-mutated urothelial carcinoma.

Given that 7.1% of all cancer types have a mutation in the FGFR pathway, there will likely be an increase in drugs that target FGFR. Knowledge of these toxicities will be necessary for optimized patient care; the most notable side effects are diarrhea, dry mouth, constipation, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, weight loss, onychauxis, and infection. 3 The known ocular side effects include central serous retinopathy (CSR), RPE detachment, dry eye, blurry vision, infectious conjunctivitis, and increased lacrimation.3,5

Our patient presented with subretinal fluid in both eyes (Figure 3) and dry-eye syndrome. To our knowledge, there are no current studies monitoring the physiologic cause of subretinal fluid and erdafitinib; however, it is a known side effect with drugs in this class. A recent study 6 evaluated the ocular effects of new and investigational epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or FGFR inhibitors based on the knowledge that FGFR is expressed in retinal tissues. 7 The study assessed 17 EGFR and FGFR inhibitors; of the 6871 patients included in the study, 16.9% had an ocular complication.

FGFR allows DNA synthesis and cell growth and prevents RPE cells from undergoing apoptosis. 8 FGFR1 can stimulate the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, leading to the synthesis of antiapoptotic protein extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 2. Creation of ERK2 activates the production of antiapoptotic proteins BCL-x and BCL-2, which downregulate apoptotic proteins Bax and caspase-3. One can surmise that inhibiting FGFR using erdafitinib targets this pathway and can inadvertently lead to apoptotic protein genesis as well as damage to and possible degeneration of RPE cells. This can lead to fluid accumulation in the retina and subsequently a condition similar to CSR. In addition, premature and mature RPE cells require the FGFR to undergo mitosis and maintain normal cell function.

When subretinal fluid is present in the retina in a patient who is currently under FGFR inhibitor treatment, one might diagnose CSR. However, in patients being treated with an FGFR/MAPK inhibitor who have subretinal fluid accumulating in the retina, the fluid is associated with MEKAR. 9

Figure 4 shows the similarities and differences between CSR and MEKAR. 10 Our patient had overlapping features. He had multifocal fluid foci with nongravitational dependency; however, he started out with a shaggy interdigitation zone (IZ). Later imaging showed that the IZ was elongated (Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Characteristics of mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor–associated retinopathy and central serous retinopathy (data adapted from Francis et al 10 ).

Most cases of MEKAR are self-resolving after the treatment is discontinued. When stability is not maintained, discontinuation of the drug should be discussed with the oncology team if the condition continues to worsen.

FGFR plays a major role in maintaining the retina and in premature and mature RPE cells. Inhibiting the FGFR signaling pathway can lead to an RPE detachment or accumulation of subretinal fluid. This is important for the patient and the prescribing physician to understand. Before starting erdafitinib therapy or another drug in this class, patients should be referred for an ophthalmologic examination to record a baseline as well as during treatment to detect low-grade ocular toxicities. Furthermore, when patients present with CSR, a thorough history should be obtained to determine whether they have taken a drug that inhibits the FGFR/MAPK pathway.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Belinda Rodriguez, ophthalmic photographer, for her technical support with the images in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The collection and evaluation of all protected patient health information was performed in a HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)–compliant manner.

Statement of Informed Consent: Written informed consent, including permission for publication of all photographs and images included herein, was obtained before the procedure was performed.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Brian Becker  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5607-3418

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5607-3418

Sophia El Hamichi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9966-0556

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9966-0556

References

- 1. Chae YK, Ranganath K, Hammerman PS, et al. Inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) pathway: the current landscape and barriers to clinical application. Oncotarget. 2017;8(9):16052-16074. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arudra K, Patel R, Tetzlaff MT, et al. Calcinosis cutis dermatologic toxicity associated with fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor for the treatment of Wilms tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45(10):786-790. doi: 10.1111/cup.13319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jansen. (n.d.). Balversa. Prescribing information. Accessed October/November 2021. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/BALVERSA-pi.pdf

- 4. Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, et al. ; BLC2001 Study Group. Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):338-348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Villegas VM, Murray TG. Alphabet soup: clinical pearls for the retina specialist-ocular toxicity of advanced antineoplastic agents in systemic cancer care. Ophthalmol Retina. 2021;5(12):1181-1186. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2021.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shin E, Lim DH, Han J, et al. Markedly increased ocular side effect causing severe vision deterioration after chemotherapy using new or investigational epidermal or fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitors. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020;20(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12886-019-1285-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kirby MA, Johnston MD. Expression of fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR 1-5) in fetal and adult human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(13):3418.15452044 [Google Scholar]

- 8. van der Noll R, Leijen S, Neuteboom GHG, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Effect of inhibition of the FGFR-MAPK signaling pathway on the development of ocular toxicities. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(6):664-672. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Parikh D, Eliott D, Kim LA. Fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(10):1101-1103. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Francis JH, Habib LA, Abramson DH, et al. Clinical and morphologic characteristics of MEK inhibitor-associated retinopathy: differences from central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(12):1788-1798. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]