Abstract

Purpose:

We present a complication of preeclampsia and hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet (HELLP) syndrome including bilateral exudative retinal detachments, bullous chemosis, and impaired ocular motility.

Methods:

The patient was followed in the inpatient and outpatient setting with clinical examinations, optical coherence tomography, widefield fundus photography, neuroimaging including magnetic resonance imaging of the brain/orbits, as well as carotid artery ultrasonography.

Results:

Our patient was admitted with bilateral vision changes in the setting of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome and was found to have bilateral exudative detachments, retinal exudation, severe bullous chemosis, and impaired motility. She was started on intravenous dexamethasone followed by an extended prednisone taper with resolution of her ocular findings and return of her vision to baseline.

Conclusions:

There is evidence that HELLP syndrome and preeclampsia are proinflammatory syndromes. Aggressive blood pressure control, corticosteroids, and a multidisciplinary approach might accelerate visual and systemic recovery in these complex cases.

Keywords: chemosis, corticosteroids, exudative detachment, HELLP, preeclampsia

Introduction

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-related disorder that commonly presents in the second to third trimester. The criteria for the diagnosis of preeclampsia include uncontrolled hypertension and proteinuria. Despite similarities to preeclampsia, hemolysis with elevated liver enzymes and low platelet (HELLP) syndrome represents a separate entity with potentially life-threatening complications that include placental abruption, acute kidney injury, and liver dysfunction.1–3 In addition to these systemic complications, preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome are both well known to cause visual complications. However, the acute and serious nature of these conditions often precludes fundus photography. We present a well-documented case of a patient who developed bilateral exudative retinal detachments in the setting of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome.

Methods

Case Report

A healthy, 24-year-old gravida 1 para 0 female presented to the hospital at 38 weeks 5 days with acute vision changes and was admitted for further evaluation. While the patient was in the inpatient and outpatient setting, she was followed with serial clinical examinations including visual acuity (VA), intraocular pressure (IOP), and pupil, anterior segment, and dilated posterior examinations. In the inpatient setting, neuroimaging including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits as well as a carotid ultrasound was performed. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) and widefield fundus photography were used to document the patient’s clinical findings when she was stable to be followed in the outpatient setting.

Results

The initial inpatient workup revealed that the patient was hypertensive (151/89 mm Hg) with an acute kidney injury (elevated protein/creatinine ratio 0.68). Throughout her hospital stay, her hepatic enzymes began to increase (aspartate aminotransferase 62 U/L; reference range, 5-40 U/L) and she developed significant thrombocytopenia (29 il/L; reference range, 150-400 bil/L). Carotid artery ultrasounds ordered because of the vision changes revealed mild atherosclerotic disease causing less than 30% diameter narrowing along the right and left carotid artery bifurcation but no significant obstruction. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with preeclampsia with a superimposed HELLP syndrome. Subsequently, she was taken for urgent cesarean delivery. Following the delivery, the patient felt that her visual symptoms had worsened and an urgent referral to ophthalmology was placed.

The initial VA was 20/40 OD and 20/25 OS, with briskly reactive pupils without an afferent pupillary defect; the IOP was normal. Initially, her extraocular motility showed no duction deficits. Bedside confrontational fields revealed bilateral superior visual defects in both eyes. An anterior segment examination was unremarkable in both eyes. Fundoscopic examination using indirect ophthalmoscopy showed bilateral exudative retinal detachments of the inferior retina with scattered retinal hemorrhages and exudation in both eyes (Figure 1).

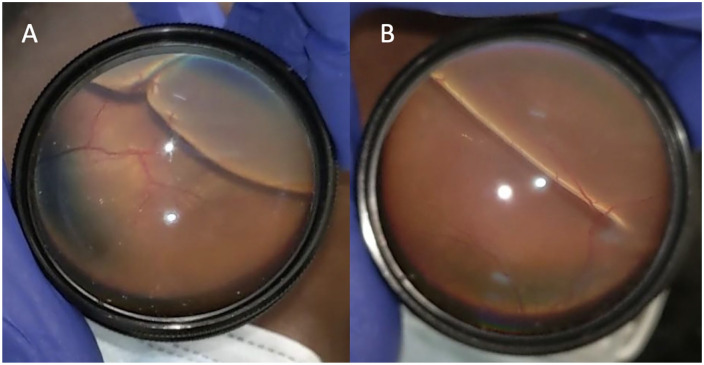

Figure 1.

Fundus photography taken at bedside using a cellular phone shows inferior bullous retinal detachments of the (A) right eye and (B) left eye.

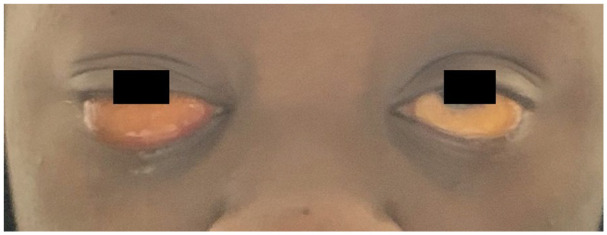

Approximately 2 days after the initial consultation, ophthalmology was paged urgently overnight for bilateral eye pain. The examination at this time showed stable VA; however, there was significant bilateral bullous chemosis with significant duction deficits in all gazes (Figure 2). Neuroimaging consisting of an MRI of the brain and orbits was performed and was considered to be benign, with no central nervous system or orbital pathology noted. Therefore, the extraocular motility restrictions were attributed to bullous chemosis from third spacing of fluid. The patient was placed on intravenous dexamethasone 10 mg twice daily; while she was an inpatient, the dexamethasone was tapered for approximately 1 week. The patient was then discharged with an oral prednisone taper at a starting dose of 40 mg, which was tapered over 1 month. In addition, the patient adhered to strict blood pressure management, diuresis, and supportive care. Her exudative detachments and chemosis rapidly began to improve.

Figure 2.

Bilateral bullous chemosis, greater than in the right eye than in the left eye.

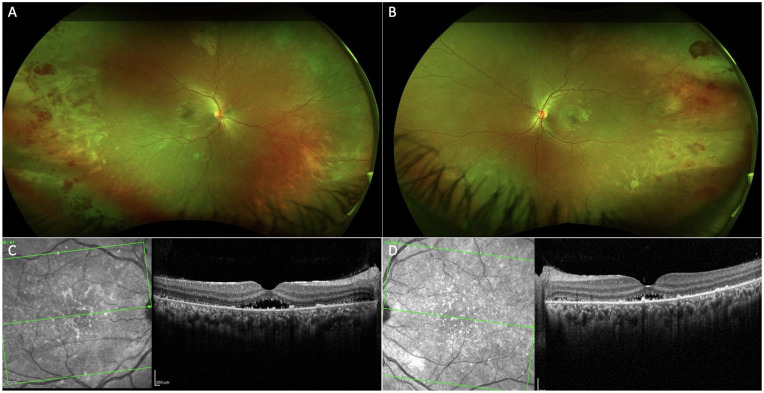

The patient was seen as an outpatient 2 weeks later with improvement in her VA to 20/25 OU; 2 months later, the VA had improved to 20/20 OU without need for refractive correction and a subjective return to her baseline vision. Funduscopic examination showed resolving retinal hemorrhages and improvement in subretinal exudates with nearly resolved exudative detachments (Figure 3, A and B). OCT showed subretinal exudation and fluid with persistent mild choroidal thickening (Figure 3, C and D).

Figure 3.

Follow-up examination 2 weeks later showed resolving inferior retinal detachments with large foci of hemorrhages and peripheral subretinal exudates in the (A) right eye and (B) left eye captured on widefield color fundus photography. Optical coherence tomography showed choroidal thickening as well as resolving subretinal exudates and subfoveal fluid in the (C) right eye and (D) left eye.

Conclusions

Preeclampsia affects approximately 3% to 5% of pregnancies and is defined as blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or greater after 20 weeks of gestation with proteinuria. 4 In addition to exudative retinal detachment, preeclampsia can lead to several other ocular and visual pathway manifestations including hypertensive retinopathy, 5 retinal arteriolar spasm, 4 cotton-wool spots, 5 macular edema, 6 retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) infarction and necrosis, 7 retinal hemorrhages, 5 posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, 8 anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, 9 and even cortical blindness. 9 Exudative retinal detachments affect approximately 0.2% to 2.0% of patients with preeclampsia and 0.9% of patients with HELLP syndrome. 10 Although the mechanism behind exudative detachments in preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome is not well defined, it has been postulated that choroidal ischemia secondary to uncontrolled hypertension results in thickening of the choroid and subsequent damage to the RPE, the combination of which impairs the RPE pump function and thus the accumulation of subretinal fluid and subsequent retinal detachment. 11

In addition to recognizing uncontrolled hypertension as a driving factor in the pathogenesis of vision loss in preeclampsia/eclampsia and HELLP syndrome, it is also important to remember that HELLP syndrome is also a state of inflammatory dysregulation. Previous reports have described elevated levels of interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, as well as other proinflammatory markers in patients with HELLP syndrome.12,13 These levels were reported to normalize after the systemic administration of steroids.12,13 Given that in vitro and in vivo studies have shown tumor necrosis factor-α secretes matrix metalloprotinease-9, resulting in disruption of the RPE tight junctions and compromise of the outer blood–retinal barrier, 14 we postulate that the use of steroids influences the inflammatory cascade and perhaps diminishes proinflammatory markers, thus restoring RPE tight junction integrity. This, in addition to blood pressure management, optimizes RPE pump function, promoting the egress of intraretinal and subretinal fluid. However, the exact mechanism and utility of corticosteroids in the management of HELLP exudative detachments and its comparison in regard to observation require further study.

Unique to our case is this patient’s conjunctival and ocular motility findings. Severe bullous chemosis is known to limit extraocular motility and can mimic cranial nerve palsy, a particularly worrisome sign in patients with elevated blood pressure and a known hypercoagulable state. Fortunately for our patient, neuroimaging was unremarkable for an acute intracranial process. Her chemosis and motility improved in accordance with normalization of serum albumin level. Thus, we believe her chemosis and ocular motility findings were likely due to third spacing of fluid given her severe hypoalbuminemia.

We present a well-documented case of a patient with preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome who developed bilateral exudative retinal detachments, severe bullous conjunctival chemosis, and restricted ocular motility. Aggressive blood pressure control and corticosteroids are mainstays of treatment in preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome but might also serve a vital role in supporting the RPE pump function, thereby promoting neurosensory retina reattachment. Given the severity of vision loss, potential for permanent damage, and multifactorial nature of these conditions, we recommend a multidisciplinary approach to provide effective management and optimize systemic and visual outcomes.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The collection and evaluation of all protected patient health information was performed in a HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)–compliant manner.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained prior to performing the procedure, including permission for publication of all photographs and images included herein.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Lisa J. Faia  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7491-2780

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7491-2780

References

- 1. Gomez-Tulub R, Rabinovich A, Kachko E, et al. Placental abruption as a trigger of DIC in women with HELLP syndrome: a population-based study. J Matern Neonatal Med. Published online September 15, 2020. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1818200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang L, Tang D, Zhao H, Lian M. Evaluation of risk and prognosis factors of acute kidney injury in patients with HELLP syndrome during pregnancy. Front Physiol. 2021;12:650826. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.650826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCormick P, Higgins M, McCormick C, Nolan N, Docherty J. Hepatic infarction, hematoma, and rupture in HELLP syndrome: support for a vasospastic hypothesis. J Matern Neonatal Med. Published online June 15, 2021. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2021.1939299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jayaraj S, Samanta R, Puthalath AS, Subramanian K. Pre-eclampsia associated bilateral serous retinal detachment. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(9):4-5. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-238358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kasai A, Sugano Y, Maruko I, Sekiryu T. Choroidal morphology in a patient with HELLP syndrome. Retin Cases Br Reports. 2016;10(3):273-277. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pastore MR, De Benedetto U, Gagliardi M, Pierro L. Characteristic SD-OCT findings in preeclampsia. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2012;43(6):139-141. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20121001-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dewilde E, Huygens M, Cools G, Van Calster J. Hypertensive choroidopathy in pre-eclampsia: two consecutive cases. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2014;45(4):343-346. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20140617-02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kini A, Tabba S, Mitchell T, Al Othman B, Lee A. Simultaneous bilateral serous retinal detachments and cortical visual loss in the PRES HELLP syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41(1):e60-e63. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maramattom BV. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy as a manifestation of HELLP syndrome. Case Rep Crit Care. 2014;2014:671976. doi: 10.1155/2014/671976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tranos PG, Wickremasinghe SS, Hundal KS, Foster PJ, Jagger J. Bilateral serous retinal detachment as a complication of HELLP syndrome. Eye (Lond). 2002;16(4):491-492. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hayreh SS, Servais GE, Virdi PS. Fundus lesions in malignant hypertension. Am Acad Ophthalmol. 1986;93(11):1383-1400. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(86)33554-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takahashi A, Kita N, Tanaka Y, et al. Effects of high-dose dexamethasone in postpartum women with class 1 haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets (HELLP) syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol (Lahore). 2019;39(3):335-339. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2018.1525609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Runnard Heimel PJ, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ, et al. HELLP syndrome is associated with an increased inflammatory response, which may be inhibited by administration of prednisolone. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2008;27(3):253-265. doi: 10.1080/10641950802174953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhou SW, Pang AYC, Poh EWT, Chin CF. Traumatic globe luxation with chiasmal avulsion. J Neuroophthalmol. 2019;39(1):41-43. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]