Abstract

Purpose:

This case report describes the unique clinical attributes of pericentral retinopathy associated with hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) use in patients of Asian ancestry.

Methods:

A complete ophthalmologic examination including optical coherence tomography, fundus autofluorescence, and Humphrey visual fields was performed. Serial images were obtained at subsequent follow-up appointments.

Results:

A dilated fundus examination demonstrated extensive bilateral parafoveal and perifoveal atrophy extending past the superior and inferior arcades as well as central macular preservation. Fundus autofluorescence exhibited prominent pericentral hypoautofluorescence.

Conclusions:

The distinct variant of pericentral hydroxychloroquine retinopathy has become increasingly recognized in patients of Asian origin. It is important for ophthalmologists to distinguish this pattern and consider modifying screening methods.

Keywords: Asian, bull’s-eye pattern, hydroxychloroquine retinopathy, pericentral retinopathy

Introduction

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ; Plaquenil, Concordia Pharmaceuticals Inc) is known to be associated with toxic retinopathy. The drug was initially designed to treat malaria, although its relevance today is most common in the treatment of rheumatologic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). 1 The prevalence of HCQ retinopathy appears considerably greater than previously recognized, possibly owing to more sensitive screening modalities. A recent large, retrospective study reported an overall incidence of retinopathy of 7.5% but with varying daily dose and duration of use of hydroxychloroquine. Furthermore, at a daily dose of 4.0 to 5.0 mg/kg, the risk of retinopathy was found to be less than 2% in patients during the first 10 years of HCQ use; however, the risk increased to nearly 20% in those with more than 20 years of HCQ use. 2

Subsequent studies have recognized an atypical pericentral pattern of retinopathy that is interestingly more prevalent in patients of Asian origin. 3,4 This appearance is in contrast to the “bull’s-eye” pattern of parafoveal damage classically seen in HCQ retinal toxicity. Screening and early detection are essential because retinopathy can continue to progress even after discontinuation of the drug. Here we present a case demonstrating an advanced pericentral pattern of retinopathy in a patient of Asian ancestry.

Methods

Case Report

A 73-year-old Asian woman with RA, chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus was referred by her general ophthalmologist for possible retinal dystrophy. She was of small stature and weighed 50.4 kilograms. The patient reported stable vision without night blindness or decreased color vision. Her ocular history was notable for a retinal problem that was diagnosed 5 years prior, which she had previously been following yearly with an outside physician. She had no known family history of retinal disease or blindness. On presentation, her RA was being controlled with methotrexate, although she had previously been on leflunomide, etanercept, and HCQ. HCQ had been stopped more than 10 years ago, but she was unsure of the dosage or duration of use.

Results

Examination revealed a visual acuity of 20/30 in the right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was normal. Confrontational visual fields were constricted in both eyes. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable in both eyes. Dilated examination revealed extensive bilateral parafoveal and perifoveal atrophy that extended past the superior and inferior arcades, both abutting the disc and extending nasally (Figure 1). There was central macular preservation. Mild pigment clumping was present along with vascular attenuation bilaterally. Both optic discs appeared healthy without pallor, and the peripheral retina was unremarkable.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Widefield fundus photography showing significant parafoveal and perifoveal retinal atrophy, extending both past the arcades and nasally with central sparing.

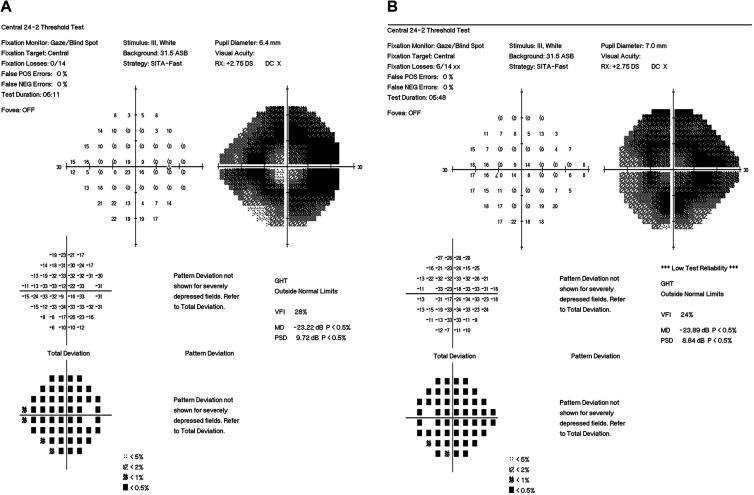

Fundus autofluorescence revealed pronounced pericentral hypoautofluorescence and loss of signal intensity corresponding to the areas of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) loss (Figure 2). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed significant outer retinal and ellipsoid zone loss, RPE attenuation, and choroidal thinning of both eyes (Figure 3). 24-2 Humphrey visual field testing showed bilateral dense ring scotomas with central sparing (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

(A and B) Widefield fundus autofluorescence imaging.

Figure 3.

(A and B) Optical coherence tomography demonstrating significant corresponding outer retinal and retinal pigment epithelium loss as well as choroidal thinning bilaterally.

Figure 4.

(A and B) 24-2 Humphrey visual fields demonstrating corresponding dense ring scotomas with central sparing. ASB indicates apostilbs; GHT, Glaucoma Hemifield Test; MD, mean deviation; PSD, pattern standard deviation; VFI, Visual Field Index.

Findings on review of systems were negative. Results from a workup for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin/fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption) were also negative.

Conclusions

Classic HCQ retinopathy has been characterized by progressive outer retinal thinning with ellipsoid loss in a parafoveal pattern, resulting in the “flying saucer” sign on spectral-domain OCT. 5 With continuous exposure RPE damage may further ensue, leading to an apparent atrophic bull’s eye maculopathy. End-stage cases of advanced toxicity may show panretinal degeneration simulating retinitis pigmentosa. 3

There is a relative paucity of literature that discusses racial differences, specifically among Asians, in HCQ toxicity. Current data suggest race may be an important component driving the primary distribution of HCQ retinopathy. A recent study showed that a high proportion of Asian patients (83%) demonstrated a pericentral (>8 degrees from the fovea) or mixed (parafoveal and pericentral) pattern of HCQ retinopathy compared with white patients (9%). 3 Furthermore, this study found that Hispanic and black patients demonstrated a predominantly parafoveal retinopathy, suggesting that pattern variance is not simply a matter of ocular pigmentation. A subsequent study investigating the pattern of HCQ retinopathy in Korean patients found that 8 out of 9 patients with HCQ toxicity presented with outer retinal changes more than 7 degrees from the fovea, consistent with a pericentral pattern. 4 An explanation as to why HCQ toxicity preferentially affects the pericentral retina in Asian patients is not clear; however, it likely involves racial differences in drug binding and/or metabolism in conjunction with pigment distribution.

In patients with early pericentral damage, the diagnosis may not be readily apparent on initial screening, which can result in a delay of HCQ discontinuation. In the previously mentioned study, compared with those who had a parafoveal pattern, patients with a pericentral or mixed retinopathy took a higher cumulative dose (2186 vs 1813 g), took the drug for a longer period of time (19.5 vs 15 years), and, not surprisingly, were diagnosed at a later stage. 3

Appropriate modification of current screening modalities is crucial for detection of early pericentral retinopathy. Adjustments could include evaluation of peripheral macula on spectral-domain OCT, examining the edge of 10-2 visual fields and/or obtaining 30-2 visual fields, and use of widefield fundus autofluorescence in some cases.

In conclusion, the pericentral pattern of HCQ retinopathy in patients of Asian ancestry warrants further promotion of awareness and appropriate screening methods given significant implications for long-term morbidity.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: Institutional review board approval was waived.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was not obtained because no patient identifiers were included.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Shippey EA, Wagler VD, Collamer AN. Hydroxychloroquine: an old drug with new relevance. Cleve Clin J Med. 2018;85(6):459–467. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.17034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Melles RB, Marmor MF. The risk of toxic retinopathy in patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(12):1453–1460. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.3459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Melles RB, Marmor MF. Pericentral retinopathy and racial differences in hydroxychloroquine toxicity. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(1):110–116. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee DH, Melles RB, Joe SG, et al. Pericentral hydroxychloroquine retinopathy in Korean patients. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(6):1252–1256. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen E, Brown DM, Benz MS. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography as an effective screening test for hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (the “flying saucer” sign). Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:1151–1158. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S14257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]