Abstract

Purpose:

This case report discusses the management of a patient with a superior chorioretinal coloboma-associated retinal detachment (RD), including surgical management, along with a review of the literature.

Methods:

A case report is presented.

Results:

A 58-year-old man presented with a chronic RD of the right eye that was symptomatic for approximately 1 year prior to presentation. On examination, he was found to have a macula-off RD associated with superior chorioretinal coloboma. He underwent 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peel, endolaser, and perfluoropropane (14%) gas tamponade. Three months after his surgery, his best-corrected visual acuity in his right eye was 20/250 distance and 20/80 near, and his retina remained attached.

Conclusions:

This case report describes surgical management of a superior chorioretinal coloboma-associated RD.

Keywords: atypical coloboma, chorioretinal coloboma, gas tamponade, retinal detachment, superior coloboma, vitrectomy

Introduction

Case Report

A 58-year-old man presented to the University of Chicago for management of his chronic superior, macula-off retinal detachment (RD) in the right eye associated with a superior chorioretinal coloboma. The patient reported severely restricted vision for at least 1 year without preceding trauma. The patient denied any history of laser treatments for the coloboma.

Methods

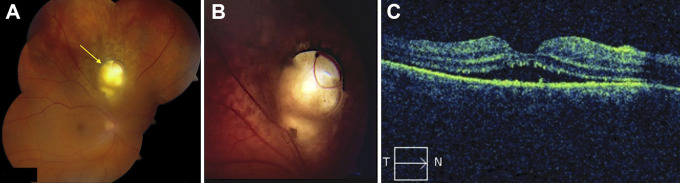

On initial evaluation, the patient was counting fingers in the right eye with no improvement on pinhole examination, and there was an afferent pupillary defect in the affected eye. Slit-lamp examination was significant for a well-placed posterior chamber intraocular lens in the right eye, and the anterior segment examination was otherwise unremarkable. Dilated fundus examination was notable for a macula-off, superior RD with grade-A proliferative vitreoretinopathy in the right eye associated with a large superior chorioretinal coloboma not involving the optic nerve head (Figure 1, A and B). Optical coherence tomography of the macula confirmed the macula-off status (Figure 1C). No peripheral retinal breaks or tears were noted on a thorough scleral-depressed examination. The left eye was 20/20 and completely normal on examination.

Figure 1.

(A) Composite fundus photograph of the right eye showing a macula-off retinal detachment from the 8 o’clock to the 3 o’clock position, associated with a superior chorioretinal coloboma (arrow). (B) Close-up image of the coloboma. (C) Macular optical coherence tomography with subretinal fluid and subretinal hyperreflective foci. T, temporal; N, nasal.

After a long discussion of risks, benefits, and alternatives for this difficult case, the patient wanted everything performed to stabilize his ocular condition and consented to proceed with a 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with membrane peel, endolaser, and gas-fluid exchange of the right eye (supplemental video). Again, no peripheral breaks were found at the start of the case. Intraoperatively, a drainage retinotomy was made superonasal to the optic disc, and most of the retina flattened during aspiration and fluid-air exchange. However, there was still substantial subretinal fluid temporal to the coloboma, including the macular region, so another drainage retinotomy was made inferotemporal to the coloboma and superior to the macular, which allowed the retina to flatten nicely. Two to three rows of 360° peripheral endolaser was performed around both posterior drainage retinotomies and the coloboma, and finally 14% perfluoropropane gas exchange was performed.

Results

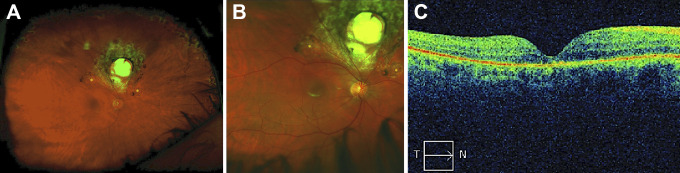

The patient’s retina was totally attached on his postoperative day 1 appointment, but he was then lost to follow-up until his 3-month visit. At that time, his best-corrected visual acuity was 20/250 at distance and 20/80 at near in the operated eye, and the preoperative afferent pupillary defect was no longer present. The retina was flat with no proliferative vitreoretinopathy (Figure 2, A and B), and the optical coherence tomography was flat with moderate photoreceptor layer atrophy (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) Optos widefield fundus photograph of the right eye showing a completely flat retina with no proliferative vitreoretinopathy, laser scarring around the superior chorioretinal coloboma and both retinotomy sites (asterisks), and peripheral 360° laser scars. (B) Close-up image of the posterior pole with coloboma. (C) Macular optical coherence tomography of the flat retina with mild photoreceptor layer atrophy. T, temporal; N, nasal.

Conclusions

Ocular colobomas (colobomata) are thought to be the result of incomplete closure of the optic cup fissure, a structure located in the inferior hemisphere of the developing human eye that normally closes in the sixth to seventh week of gestation. The prevalence of ocular colobomata has been reported to be 1 out of every 2077 to 5000 live births, 1,2 and they are responsible for 3% to 11% of blindness in pediatric patients. 2 Colobomata range in severity and may involve the iris, ciliary body, lens, retina, retinal pigment epithelium, Bruch membrane, choroid, and optic nerve. 3,4 Colobomata may also be associated with systemic syndromes such as CHARGE syndrome (coloboma, heart defects, atresia of the choanae, growth retardation, genitourinary and ear abnormalities), MPPC syndrome (microcornea, posterior megalolenticonus, persistent fetal vasculature, chorioretinal coloboma), oculo-digital-dental syndrome, chromosome 22q11 gene deletion (DiGeorge syndrome), and, rarely, Marfan syndrome. 1,4 -6 Common complications of chorioretinal colobomata include retinal breaks, rhegmatogenous RDs, and choroidal neovascularization. 4

Many retinal breaks and rhegmatogenous RDs occur at the margin of the coloboma. Previous authors have demonstrated that the inner layers of the neurosensory retina extend centrally into the coloboma, forming a structure referred to as the intercalary membrane, whereas the outer retinal layers become disorganized at the coloboma margin and have little glial support. Schisislike changes occur, and a locus minoris resistentiae is formed that eventually leads to a retinal break and/or RD at the coloboma margin. 7 -9 Retinal breaks have also been reported outside the coloboma, leading previous authors to suggest that an abnormal vitreoretinal interface may also be partly responsible for coloboma-associated retinal breaks and RDs.

Retinal breaks associated with colobomata have been treated similarly to retinal breaks from other pathologies, typically with laser photocoagulation or cryotherapy. 4

The prevalence of coloboma-associated RDs has been reported to be 2.4% to 42%. 3,4,10 Management of coloboma-associated RDs has included pars plana vitrectomy with silicone oil or gas tamponade, endolaser photocoagulation, and/or cryotherapy. 9,11 -13 Scleral buckling has also been described but appears to have limited success, likely because of difficulty in identifying breaks in the intercalary membrane, posterior location of the break, and lack of normal retinal pigment epithelium underlying the break, leading to a lack of adequate chorioretinal adhesion. 9,12 Reattachment rates have been reported to be 35% to 100% 4,11,12 and were reported to be 75% in a large review of 85 eyes with surgically managed coloboma-associated RDs. 4,11

Coloboma-associated choroidal neovascularization is likely caused by breaks in the Bruch membrane at the edges of the coloboma as a result of the mechanisms described above. It has been successfully treated with observation, laser photocoagulation, intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor therapy, and/or photodynamic therapy. 4

Few reported cases of superior chorioretinal colobomata have been reported. 2,14,15 Because the optic cup fissure is a structure in the inferior hemisphere of the developing eye, superior colobomata must form from a different mechanism. In their report of a series of 8 patients with superior colobomata, Hocking et al 2 have proposed a novel model of development. They suggest that superior colobomata may form from a maldevelopment of a superior ocular sulcus. The superior ocular sulcus is a structure identified in the developing eyes of fish, chicks, and mice. Through exome sequencing, Hocking and colleagues have identified rare gene variants controlling the expression of bone morphogenetic protein receptor and T-box transcription factors as being associated with superior colobomata. Furthermore, by manipulating gene sequences in zebrafish, they have shown that disrupting the normal expression of these genes results in a phenotype similar to the superior colobomata seen in the patients in their case series. 2

Of the patients in the Hocking case series, only 3 had superior chorioretinal colobomata, and of these only 1 had an associated defect in another ocular structure (the iris). 2 In addition, Jain et al 14 reported a case of a 38-year-old woman with a superior chorioretinal coloboma associated with an iris coloboma, and an “hourglass” chorioretinal coloboma was reported in a case report by Kumar and colleagues 15 in which multiple chorioretinal colobomata were present in the same eye. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, these are the only reported cases of superior chorioretinal colobomata similar to the coloboma in our patient, but our patient is the only report of a superior coloboma-associated RD.

Multiple theories regarding the pathophysiology of “atypical” ocular colobomata have been postulated. 2,15,16 Our case supports the theory of Hocking et al 2 , in that there are likely other developing structures in the human eye in addition to the known inferior optic fissure, perhaps a superior ocular sulcus, that must play a role in the development of the normal human eye. A similar theory described long ago of “accessory embryonic fissures” that may be present in developing eyes could lead to a coloboma in any quadrant of the developing eye. These accessory fissures have been observed in sheep and chick embryos but have never been demonstrated in developing human eyes. 15,16

Another theory suggests that abnormal cyclorotation of ocular structures during development may lead to an “atypical” position of a typical coloboma that was formed from maldevelopment of the inferior ocular fissure. However, in cases of abnormal cyclorotation during development, other ocular structures (eg, extraocular muscles, macula, optic nerve) would be expected to be rotated or mispositioned as well, which is not seen in these patients. 15,16 Therefore, we do not believe that abnormal cyclorotation is likely to be the cause of the atypical coloboma position in our patient.

Our case is unique in that it is one of the few reports of a superior chorioretinal coloboma, and to our knowledge it is the first reported description of the surgical repair of a superior coloboma-associated RD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The collection and evaluation of all protected patient health information were performed in a HIPAA- (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)-compliant manner.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained prior to administering care to the patient, including permission to use clinically acquired data and images for publication.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Sidney A. Schechet, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8996-3855

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8996-3855

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material is available online with this article.

References

- 1. Nakamura KM, Diehl NN, Mohney BG. Incidence, ocular findings, and systemic associations of ocular coloboma: a population-based study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(1):69–74. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hocking JC, Famulski JK, Yoon KH, et al. Morphogenetic defects underlie superior coloboma, a newly identified closure disorder of the dorsal eye. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(3):e1007246. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Suwal B, Paudyal G, Thapa R, Bajimaya S, Sharma S, Pradhan E. A study on pattern of retinal detachment in patients with choroidal coloboma and its outcome after surgery at a tertiary eye hospital in Nepal. J Ophthalmol. 2019;2019:7390852. doi:10.1155/2019/7390852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hussain RM, Abbey AM, Shah AR, Drenser KA, Trese MT, Capone A, Jr. Chorioretinal coloboma complications: retinal detachment and choroidal neovascular membrane. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2017;12(1):3–10. doi:10.4103/2008-322X.200163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rothfield LD, Cernichiaro-Espinosa LA, Alabiad CR, et al. Microcornea, posterior megalolenticonus, persistent fetal vasculature, chorioretinal coloboma (MPPC) syndrome: case series post vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019;14:5–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gupta G, Goyal P, Malhotra C, Jain A. Bilateral lens coloboma associated with Marfan syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(8):1192. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_542_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schubert HD. Schisis-like rhegmatogenous retinal detachment associated with choroidal colobomas. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233(2):74–79. doi:10.1007/bf00241475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schubert HD. Structural organization of choroidal colobomas of young and adult patients and mechanism of retinal detachment. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2005;103:457–472. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.026 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Abouammoh MA, Alsulaiman SM, Gupta VS, et al. ; King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (KKESH) International Collaborative Retina Study Group. Surgical outcomes and complications of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in eyes with chorioretinal coloboma: the results of the KKESH International Collaborative Retina Study Group. Retina. 2017;37(10):1942–1947. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Daufenbach DR, Ruttum MS, Pulido JS, Keech RV. Chorioretinal colobomas in a pediatric population. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(8):1455–1458. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(98)98028-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gopal L, Badrinath SS, Sharma T, et al. Surgical management of retinal detachments related to coloboma of the choroid. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(5):804–809. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(98)95018-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramezani A, Dehghan MH, Rostami A, et al. Outcomes of retinal detachment surgery in eyes with chorioretinal coloboma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2010;5(4):240–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hocaoglu M, Karacorlu M, Ersoz MG, Sayman Muslubas I, Arf S. Outcomes of vitrectomy with silicone oil tamponade for management of retinal detachment in eyes with chorioretinal coloboma. Retina. 2019;39(4):736–742. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jain A, Ranjan R, Manayath G. Atypical superior iris and retinochoroidal coloboma. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(10):1474–1475. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_531_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar M, Shanmugam M, Sagar P, Kumar D, Konana VK. “Hourglass coloboma”: a case report and review of etiopathogenesis [published online July 24, 2018]. Retin Cases Brief Rep. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000000810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gifford SR. Atypical coloboma of the iris and choroid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1920;3(2):97–103. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(20)90033-8 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.